Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Daily Activity Budget of Nicobar Long-Tailed Macaque (Macaca Fascicularis Umbrosa) in Great Nicobar Island, India

Hochgeladen von

researchinbiology0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

68 Ansichten10 SeitenNicobar long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa Miller, 1902) are distributed in three Islands of Nicobar namely Great Nicobar, Little Nicobar and Katchal. Their insular population requires special attention from research and management perspectives. Daily activity budget of M.f. umbrosa in the Great Nicobar Island was studied from October 2011 to September 2013 by intensive direct observation method. Study revealed that Nicobar long-tailed macaque, undergoes most of the time for Locomotion (36.07%), followed by feeding (22.35%), resting or being inactive (15.74%), grooming (11.14%), vocalization (7.03%), playing (5.64%), sexual arousal (1.46%) and agonistic (0.56%). All daily activities have significant difference (χ2 = 1156.22; df = 7, P = 0.05). Chi-square test demonstrated that the daily activity budget differed significantly among the behaviours. Qualitative results found that the interaction within the group was fighting and grabbing food. The significant observation of disability in their legs was noticed in Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque. The relation between their behaviour and disability is also discussed.

Article Citation:

Rajeshkumar S, Raghunathan C, Kailash Chandra and Venkataraman K.

Daily Activity Budget of Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa) in Great Nicobar Island, India.

Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347.

Full Text:

http://jresearchbiology.com/documents/RA0447.pdf

Originaltitel

Daily Activity Budget of Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa) in Great Nicobar Island, India

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenNicobar long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa Miller, 1902) are distributed in three Islands of Nicobar namely Great Nicobar, Little Nicobar and Katchal. Their insular population requires special attention from research and management perspectives. Daily activity budget of M.f. umbrosa in the Great Nicobar Island was studied from October 2011 to September 2013 by intensive direct observation method. Study revealed that Nicobar long-tailed macaque, undergoes most of the time for Locomotion (36.07%), followed by feeding (22.35%), resting or being inactive (15.74%), grooming (11.14%), vocalization (7.03%), playing (5.64%), sexual arousal (1.46%) and agonistic (0.56%). All daily activities have significant difference (χ2 = 1156.22; df = 7, P = 0.05). Chi-square test demonstrated that the daily activity budget differed significantly among the behaviours. Qualitative results found that the interaction within the group was fighting and grabbing food. The significant observation of disability in their legs was noticed in Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque. The relation between their behaviour and disability is also discussed.

Article Citation:

Rajeshkumar S, Raghunathan C, Kailash Chandra and Venkataraman K.

Daily Activity Budget of Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa) in Great Nicobar Island, India.

Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347.

Full Text:

http://jresearchbiology.com/documents/RA0447.pdf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

68 Ansichten10 SeitenDaily Activity Budget of Nicobar Long-Tailed Macaque (Macaca Fascicularis Umbrosa) in Great Nicobar Island, India

Hochgeladen von

researchinbiologyNicobar long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa Miller, 1902) are distributed in three Islands of Nicobar namely Great Nicobar, Little Nicobar and Katchal. Their insular population requires special attention from research and management perspectives. Daily activity budget of M.f. umbrosa in the Great Nicobar Island was studied from October 2011 to September 2013 by intensive direct observation method. Study revealed that Nicobar long-tailed macaque, undergoes most of the time for Locomotion (36.07%), followed by feeding (22.35%), resting or being inactive (15.74%), grooming (11.14%), vocalization (7.03%), playing (5.64%), sexual arousal (1.46%) and agonistic (0.56%). All daily activities have significant difference (χ2 = 1156.22; df = 7, P = 0.05). Chi-square test demonstrated that the daily activity budget differed significantly among the behaviours. Qualitative results found that the interaction within the group was fighting and grabbing food. The significant observation of disability in their legs was noticed in Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque. The relation between their behaviour and disability is also discussed.

Article Citation:

Rajeshkumar S, Raghunathan C, Kailash Chandra and Venkataraman K.

Daily Activity Budget of Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa) in Great Nicobar Island, India.

Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347.

Full Text:

http://jresearchbiology.com/documents/RA0447.pdf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 10

Article Citation:

Rajeshkumar S, Raghunathan C, Kailash Chandra and Venkataraman K.

Daily Activity Budget of Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa) in

Great Nicobar Island, India.

Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

R

e

s

e

a

r

c

h

i

n

B

i

o

l

o

g

y

Daily Activity Budget of Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque

(Macaca fascicularis umbrosa) in Great Nicobar Island, India

Keywords:

Macaca fascicularis umbrosa, Daily activity budget, Great Nicobar Island

ABSTRACT:

Nicobar long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa Miller, 1902) are

distributed in three Islands of Nicobar namely Great Nicobar, Little Nicobar and

Katchal. Their insular population requires special attention from research and

management perspectives. Daily activity budget of M.f. umbrosa in the Great Nicobar

Island was studied from October 2011 to September 2013 by intensive direct

observation method. Study revealed that Nicobar long-tailed macaque, undergoes

most of the time for Locomotion (36.07%), followed by feeding (22.35%), resting or

being inactive (15.74%), grooming (11.14%), vocalization (7.03%), playing (5.64%),

sexual arousal (1.46%) and agonistic (0.56%). All daily activities have significant

difference (2 = 1156.22; df = 7, P = 0.05). Chi-square test demonstrated that the daily

activity budget differed significantly among the behaviours. Qualitative results found

that the interaction within the group was fighting and grabbing food. The significant

observation of disability in their legs was noticed in Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque. The

relation between their behaviour and disability is also discussed.

1338-1347 | JRB | 2014 | Vol 4 | No 4

This article is governed by the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by/2.0), which gives permission for unrestricted use, non-commercial, distribution and

reproduction in all medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

www.jresearchbiology.com

Journal of Research in Biology

An International

Scientific Research Journal

Authors:

Rajeshkumar S

1*

,

Raghunathan C

1

,

Kailash Chandra

2

and

Venkataraman K

2

.

Institution:

1. Zoological Survey of

India, Andaman and Nicobar

Regional Centre, Port Blair-

744 102, Andaman and

Nicobar Islands, India.

2. Zoological Survey of

India, M-Block, New

Alipore, Kolkatta-700 053,

India.

Corresponding author:

Rajeshkumar S.

Email Id:

Web Address:

http://jresearchbiology.com/

documents/RA0447.pdf.

Dates:

Received: 01 Apr 2014 Accepted: 30 May 2014 Published: 24 Jun 2014

Journal of Research in Biology

An International Scientific Research Journal

Original Research

ISSN No: Print: 2231 6280; Online: 2231- 6299

INTRODUCTION

Primates are maintaining the sustainable

ecosystem and play as indicator for ecosystem health;

hence, they help in making of conservation and

management plans. Non-human primates of undisturbed

areas are having great behavioural variation (Thomas,

1991) which are closely related to human beings such as

eating, playing, fighting, keeping young ones etc. (Rod

and Preston-Mafham, 1992). The daily activities and

behaviour of primates differ between residential, non-

residential and undisturbed areas (Krebs and Davies,

1993). Large group size, poor habitat quality, seasonal

variation in food availability may affect their daily

activity budget (Peres, 1993; Passamani, 1998). The

Long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa

Miller, 1902) are the only non-human primates found on

Nicobar Islands (Umapathy et al., 2003). Other

subspecies occur in Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos,

Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and the

Philippines (Rodman, 1991; Tikader and Das, 1985).

This species varies in their behaviour, social

organisations, habitat consumption, morphology and

genetic variation due to wide distribution (Brent and

Veira, 2002; Hamada et al., 2008). Previous researches

in Nicobar subspecies are available for population status

and distribution profiling (Umapathy et al., 2003;

Sivakumar, 2010; Narasimmarajan and Raghunathan,

2012) Study on ecology and behaviour are also focused

in the other subspecies of Long-tailed Macaque in South

East Asian countries. Reports are available on the

aggressive and social behaviour of M. fascicularis

(Nordin and Jasmi, 1981; Zamzarina, 2003; Brent and

Veira, 2002; Khor, 2003; Md-Zain et al., 2003; Siti,

2003). The present study is focused on the daily activity

budgets of M f. umbrosa in Great Nicobar Island.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area

The Great Nicobar Island is about 1045.1 sq km

comprises of Campbell bay National Park and Galathea

National Park (Fig. 1). These two National Parks

embrace Great Nicobar Biosphere Reserve (GNBR). The

study site covers about 3 km

2

and is composed of low

hills near dense semi evergreen forest, Maggar Nallah

river and human Settlements at Govind Nagar (06

59.985' N 093 54.459' E) and it is 6 km away from

Campbell Bay (Fig. 1). GNBR has richest faunal and

Rajeshkumar et al., 2014

1339 Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347

Fig 1. Study area and Study site.

floral communities. Great Nicobar is the home for plants

like Albizia chinensis, Albizia lebbeck, Artocarpus

chaplasha, Calophyllum soulattri, Dipterocarpus sp.,

Pterocarpus sp., and Sterculia campanulatum. In fauna,

other than the long-tailed macaques, the endemic

mammals recorded are Nicobar wild boar (Sus scrofa

nicobaricus), Nicobar Tree shrew (Tupaia nicobarica),

Nicobar shrew (Crocidura nicobarica) and Nicobar

Flying fox (Pteropus faunulus).

Behaviour Sampling Method

Following the methods of Hambali et al., (2012);

Md-Zain et al., (2008b) and Brent and Veira (2002) daily

activity observations of macaque were made during 2 to

3 days in a week at 0500 hours until 1630 hours for 78

days from October 2011 to September 2013 to determine

the behaviour categories. A study group categories and

its composition of the three consecutive years are given

in Table. 1. The total number of individuals in study

group increased year by year i:e from 37 to 51

individuals. Every year the numbers of females were

more than that of males. This group was marked by their

dominant male who had a distinctive large and elongated

white area between the eyes and white eyelids compared

to the other groups. Focal animal sampling method was

adopted to collect the quantitative data at ten minutes

interval (Altmann, 1974; Lehner, 1979). During

torrential rain and adverse weather condition, the

observation was discontinued until the weather resumes

normally, because the animals were partially obscured or

moved completely from the observation sites. The data

on the observations of locomotion, feeding, resting,

grooming, vocalization, playing, sexual arousal and

agonistic were collected during the study. Chi-square test

was applied to analyse the behaviour data set obtained.

The nonparametric 2 test was used to analyze the

significance of activity budgets.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Result on the percentage of eight daily activities

of Nicobar long-tailed macaques monitored is given in

Table 2. Chi-square analysis upon the present study

indicated that all the eight behavioural observation shows

significant differences (Table 2). Jaman and Huffman

(2008) observed that, activities of Japanese macaque

(M. fuscata) in captivity varied between age-sex classes.

Similarly the behavioural variation occurred in

individual with different age-sex observed in the present

study. The most observed daily activity for all the age

group was locomotion. The locomotion is the highest

portion of daily activity in long-tailed macaques

compared to other activities (Hambali et al., 2012; Md-

Zain et al., 2010; Sia, 2004; Suhailan, 2004). This is

because of diurnal in nature as they are very active

during the day as they use their maximum time in

searching for food.

Locomotion

According to Menard (2004) and Wheatley

(1980) Long-tailed Macaques are the primates spending

most of their time for moving as they are mainly

frugivorous and occupy more space. It was also observed

that the study groups moving choice is varied day by

day to different location and range. When they move out

Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347 1340

Rajeshkumar et al., 2014

Group categories Adult (Mature) Immature

Total No. of Individual

Year Male Female Total Sub Adult Juvenile Infant

2011 (October) 10 13 23 10 3 1 37

2012 (March) 12 15 27 12 4 2 45

2013 (August) 13 16 29 12 6 4 51

Table 1. Year wise group composition and total number of Individuals in the study group.

of their home range, there was a shortage of food sources

and availability of fruits. According to OBrien and

Kinnaird (1997), availability of food source significantly

affects their locomotion in daily activity pattern.

Sometimes these animals visit human settlement areas

and raids crop land, coconuts farms and banana farms

which lead to their destruction. The result indicates that

the macaque spent most of the time in moving due to the

insufficient food sources in their habitat. Likewise this

study group also spend most of their time to visit

different localities because of their diminishing natural

food sources.

Feeding

Besides locomotion, feeding was observed as one

of the major activities of macaque during the study (Fig.

2 A). It resembles with the other subspecies studied by

Hambali et al., (2012), Md-Zain et al., (2010), Suhailan

(2004) and Tuan-Zaubidah (2003) who all found that

feeding is the second most occurrence activity compared

to other. However this finding was contradict with other

macaque species. For example Southern India wild lion-

tailed macaque (Kurup and Kumar, 1993) and captive

Japanese macaque (Jaman and Huffman, 2008) spend the

highest proportion of time in resting rather than feeding

depending on the food and weather factor. An increase in

one activity may pose some influence on other activities

(Jaman and Huffman, 2008). The main food sources are

fruits, flowers, tender leaves, insects, crabs, beetles,

butterflies, some spiders, grasshopper etc. Usually

macaque feed insects in afternoon period between resting

and grooming. When the food sources are less long-

tailed macaque usually rest.

Resting

Resting is the third most activity observed in our

study (Fig. 2 B). The result of the study revealed that

prolonged feeding activity considerably reduced the

resting behaviour during the observation from macaque

in Great Nicobar as noticed by Hambali et al., (2012) in

Malayan long-tailed macaque and Kurup and Kumar

(1993) in lion-tailed macaque. Resting includes activities

like sleeping, lying down and to sit idle. Macaques were

observed resting on tree branches, dead woods, bushes,

rocks and sometimes resting on the roads. Also they use

to take a few minutes rest after walking continuously.

Rainy season and unusual climate directly affect their

feeding and moving activities and increase their resting

Rajeshkumar et al., 2014

1341 Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347

Activity Observation Percentage (%) Expected frequency

2

= (O-E)

2

/E

Locomotion 518 36.07 179.5 638.34*

Feeding 321 22.35 179.5 111.54*

Resting 226 15.74 179.5 12.04*

Grooming 160 11.14 179.5 2.12*

Vocalization 101 7.03 179.5 34.33*

Playing 81 5.64 179.5 54.05*

Sexual 21 1.46 179.5 139.95*

Agonistic 08 0.56 179.5 163.85*

Total 1436 100 1436 1156.25

Table 2. Percentage and Chi-square value of Nicobar long-tailed macaques daily activity.

* Showing significant differences (p<0.05), by using the chi-square test (

2

).

Degrees of freedom (df) = 7, O-Observation, E-Expected frequency.

activity. During night time, macaques sleep on the top of

tree branches. This behaviour indicates that the macaque

protect themselves from the predators. The only known

predator is reticulated python (Broghammerus

reticulatus) as no other higher predators are found in

Great Nicobar Island, but the anthropogenic activity and

domestic predators like dogs also affects their normal

activity.

Grooming

Grooming is the fourth highest activity observed

after resting (Fig. 2 C). This result is similar with M.

fascicularis found in Kuala Selangor Nature Park,

Malaysia (Hambali et al., 2012). Most of their grooming

activity occurs at the time of resting period. It was

predominantly observed at late afternoon when the

macaques return to the home range. At the time of

grooming one monkey picks up lice from others body.

Most of the individuals often prefer to self-groom rather

than social grooming. Social grooming highly noticed

between the adult female and adult male. Observations

on grooming between the adult female with infants were

least due to the presence of only few infant in the group.

There was a least observation on grooming between

adult female and juveniles as well as sub adults. Self-

grooming was also often observed in sub adults and

secluded male at the time of resting. In addition, after

mating, the dominant male is groomed by female.

According to Lazaro-perea et al., (2004) this behaviour

can be a way to get protection from others while fighting

and also for sharing of food.

Vocalization

Vocalization is the fifth behaviour that has been

observed. When the agonistic interaction occurs between

the group individuals, dominant adult male produce loud

calls and all the other individuals sound continuously. In

general, macaque produces loud calls especially for

Rajeshkumar et al., 2014

Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347 1342

Fig 2. Various activities of Long-tailed Macaque in Great Nicobar Island

A. Feeding, B. Resting, C. Grooming, D. Playing, E. Mating, F. Agonistic.

grabbing and snatching food item and fighting with their

group member. In addition during agonistic interaction

within the group or entrance of predatory animals such as

dogs in their territory, macaque used to make

vocalization. Normally vocalization can be treated as a

warning signal to protect themselves from predators as

observed by Md-Zain et al., (2010). Due to the

observers or the humans activity in their range,

macaque produce different sounds and mainly the sub

adults seem to be most active as they used to climb very

quickly and keep other individuals alert. Members of the

group after hearing the vocal call warning used to climb

to higher ground to escape or hide in bushes. We

observed a least number of calls produced by macaques

while playing activity. Kipper and Todt (2002) and Md-

Zain et al., (2010) also found that the vocal call was

produced by macaques while playing. In the present

study the male long-tailed macaques were found to

produce vocal calls while grooming after mating. No

females were observed producing vocals during mating.

On the other hand observation made by Md-Zain et al.,

(2010) showed that females were found to produce vocal

during and after mating. The possible reason for this

behaviour can be a hormonal effect (Engelhardt et al.,

2005).

Playing

Playing activity is the sixth behaviour that has

been observed during the study period (Fig. 2 D). We

found predictable differences in playing activity in the

juveniles and sub adults. Juveniles were found to play

more than sub adults. Adult macaques were not involved

in playing activity. The playing behaviour may form a

social competition and juveniles in their active age

period will learn on social relations (Kipper and Todt,

2002). Usually, playing behaviour was observed in the

late afternoon, when adult long-tailed macaques are

inactive. Wrestling, chasing, tickling, swinging on the

tree branches, pulling their tails to play with one another

and invert hanging and jumping were the playing

categories observed during the study. It was also

observed that these animals prefer playing on the

selected trees like Casuarinas, Pandanus, Guava and

Coconut. In the evening, all the group member moves

near sleeping site and while moving many were found

collecting and eating some insects in the bushy area.

Sexual Arousal

Sexual behaviour like mating, mount, inspect

copulation are the categories were observed as the

seventh activity (Fig. 2 E). In our study period dominant

males were actively involved in mating with adult

females as this may help females in giving birth to

healthy generation. Females use to live with multimale

group, focused in copulating with dominant males as

observed by Hambali et al., (2012), Lawler et al., (1995),

Md-zain et al., (2010) and Van Noordwijk and Van

Schaik (1999). Sexual behaviour observed is only a small

portion of daily activity in long-tailed macaque.

Normally the adult male was found to smell or observe

the adult female genitalia first to make sure that the

females are ready to mate or not which is in corroborated

with the report of Brent and Veira (2002), Md Zain et al.,

(2010) and Hambali et al., (2012). The long-tailed

macaque takes a few seconds for mating activity.

Agonistic Activity

The least observed activity is the agonistic

behaviour (Fig. 2 F). During our study chase, grab, hit,

bite and fight are the categories of agonistic behaviour

observed as the eighth activity. Though these behaviours

are supported by Hambali et al., (2012), Md-Zain et al.,

(2010), Suhailan (2004) and Tuan-Zaubidah (2003) they

found that mating is the least observed activity. Fighting

behaviour occurred while gaining foods and mates.

Hambali et al., (2012) found that Malay wild long-tailed

macaque has a hierarchy in the group, so that they have

their own way to avoid fight when looking for food

together. Chasing and biting occur sometime between the

males and sub adults. Adult male were more aggressive

when their food was grabbed by other males, this shows

Rajeshkumar et al., 2014

1343 Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347

that the aggression appeared in males higher than

females which is agreed with the Brent and Veira (2002)

from macaque observed at Indo-China population.

Significantly we observed few aggressive activities in the

Nicobar long-tailed macaque against human beings

especially women and children during the study period.

Disability and Behaviour

During our study period several disabled

macaques were spotted (Fig 3). They were not able to

move properly due to their disability. These disabilities

may cause some changes in their daily activities which in

turn will cause changes in their behaviour like

locomotion, disability in finding mates, foraging

activities, etc. The relation between disability and

behaviour is also reported in Japanese macaques

(Macaca fuscata) by Turner et al., (2012). The possible

causes of disabilities are congenital defects, dog chasing

and anthropogenic activities. However, exact cause of

disability was not known. But this significant

observation may throw some light on the threats and

their status of these monkeys.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study enlightened behavioural and

activity patterns of the long-tailed macaque population

living in the Great Nicobar Island. It is revealed that

Rajeshkumar et al., 2014

Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347 1344

Fig 3. Disability in Nicobar Long-tailed macaque

A. Forearm partially disabled, B. Foreleg disabled, C. Hindleg partially disabled.

locomotion, feeding and resting were the most common

daily activities of these monkeys. Disabled macaques

spotted during our study period may give some

information on the changes in their behaviour that occur

due to disability as well as on the threats they use to

encounter. This study also found that the aggressive

behaviour against humans may raise the issue of human-

macaque conflict. Further studies on the specific impact

of crop raiding and feeding behaviour will derive the

implication of its conservation and management

strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Ministry of

Environment and Forests, Government of India. The

logistic support provided by Divisional Forest officer,

Nicobar Division, Campbell Bay is duly acknowledged.

REFERENCES

Altmann J. 1974. Observational study of behaviour:

Sampling methods. Behaviour. 49(3): 227-267.

Brent L and Veira Y. 2002. Social behaviour of captive

IndoChinese and Insular long-tailed macaques (Macaca

fascicularis) following transfer to a new facility. Int. J.

Primatol., 23(1): 147-159.

Engelhardt A, Hodges JK, Niemitz C and

Heistermann M. 2005. Female sexual behaviour, but

not sex skin swelling, reliably indicates the timing of the

fertile phase in wild long-tailed macaques (Macaca

fascicularis). Horm. Behav., 47(2): 195-204.

Hamada Y, Suryobroto B, Goto S and Malaivijitnond

S. 2008. Morphological and body color variation in Thai

Macaca fascicularis fascicularis North and South of the

Isthmus of Kra. Int. J. Primatol., 29(5): 1271-1294.

Jaman MF and Huffman MA. 2008. Enclosure

environment affects the activity budgets of captive

Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata). Am. J. Primatol.,

70(12): 1133-1144.

Kamarul Hambali, Ahmad Ismail and Badrul Munir

Md-Zain. 2012. Daily Activity Budget of Long-tailed

Macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in Kuala Selangor

Nature Park. Int. J. Basic and Applied Sciences. 12(4):

47-52.

Khor OP. 2003. Kajian kelakuan Macaca fascicularis

dan interaksi dengan manusia di Taman Belia, Pulau

Pinang. Tesis sarjana muda, Universiti Kebangsaan,

Malaysia.

Kipper S and Todt D. 2002. The use of vocal signals in

the social play of Barbary Macaques. Primates. 43(1): 3-

17.

Krebs JR and Davies NB.1993. An introduction to

behavioural ecology. Wiley-Blackwell Scientific

Publications, London.

Kurup, GU and Kumar A. 1993. Time budget and

activity patterns of the Lion-Tailed Macaque (Macaca

silenus). Int. J. Primatol., 14(1): 27-39.

Lawler SH, Sussman RW and Taylor LL. 1995.

Mitochondrial DNA of the Mauritian macaques (Macaca

fascicularis): An example of the founder effect. Am. J.

Phys. Anthropol., 96(2): 133-141.

Lazaro-Perea C, De Arruda MF and Snowdon CT.

2004. Grooming as a reward? Social function of

grooming between females in cooperatively breeding

marmosets. Anim. Behav., 67(4): 627-636.

Lehner PN. 1979. Handbook of Ethological Methods.

New York: Garland STPM Press.

Md-Zain BM, Norhashimah MD and Idris AG. 2003.

Long-tailed macaque of the Taman Tasik Taiping: Its

social behaviour. Prosiding Simposium Biologi Gunaan

ke. 7: 468-470.

Rajeshkumar et al., 2014

1345 Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347

Md-Zain BM, Yen MY and Ghani IA. 2008b. Daily

activity budgets and enrichment activity effect on

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in captivity. Sains

Malaysiana. 37(1): 15-19.

Md-Zain BM, Shaari NA, Mohd-Zaki M, Ruslin F,

Idris NI, Kadderi MD and Idris WMR. 2010. A

comprehensive population survey and daily activity

budget on long-tailed macaques of Universiti

Kebangsaan Malaysia. Journal of Biological Sciences. 10

(7): 608- 615.

Menard N. 2004. Do Ecological Factors Explain

Variation in Social Organizations? In: Macaque

Societies: A Model for the Study of Social Organization,

Thierry, B., M. Singh and W. Kaumanns (Eds.).

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Narasimmarajan. K and Raghunathan. C. 2012.

Status of Long Tailed Macaque (Macaca fascicularis

umbrosa) and conservation of the recovery population in

Great Nicobar Island, India. Wildl. Biol. Pract., 8(2): 1-8

Nordin M and Jasmi DA. 1981. Jarak antara individu

dan lakuan agresif pada Macaca fascicularis tawanan

dan liar. Sains malaysiana. 10(2): 107-122.

OBrien TG and Kinnaird MF. 1997. Behaviour, diet

and movements of the Sulawesi crested black macaque

(Macaca nigra). Int. J. Primatol., 18(3): 321-351.

Passamani M. 1998. Activity budget of Geoffroys

Marmoset (Callithrix geoffroyi) in an Atlantic forest in

Southeastern Brazil. Am. J. Primatol., 46(4): 333-340.

Peres CA. 1993. Diet and feeding ecology of Saddle-

back (Saguinus fuscicollis) and moustached (S. mystax)

tamarins in an amazonian Terra firme forest. J. Zool.,

230(4): 567-592.

Rod and Preston-Mafham K. 1992. Primates of the

World. London. Blandford Villiers House.

Rodman PS. 1991. Structural differentiation of

microhabitats of sympatric Macaca fascicularis and M.

nemestrina in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Int. J.

Primatol., 12(4): 357375.

Sarah E. Turner, Linda M. Fedigan, Damon

Matthews H and Masayuki Nakamichi. 2012.

Disability, Compensatory Behaviour, and Innovation in

Free-Ranging Adult Female Japanese Macaques

(Macaca fuscata). Am. J. Primatol., 74 (9): 788803

Sia WH. 2004. Kajian kelakuan Macaca fascicularis di

kawasan sekitar kampus UKM. Thesis, S.Sn. Universiti

Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Siti JA. 2003. Kajian terhadap kehadiran Macaca dan

interaksi dengan manusia di Taman Tasik Taiping,

Perak. Tesis, Sarjana Muda. Universiti Kebangsaan

Malaysia.

Sivakumar K. 2010. Impact of the tsunami (December,

2004) on the long tailed macaque of Nicobar Islands,

India. Hystrix It. J. Mamm. (n.s).21 (1): 35-42.

Suhailan WM. 2004. A behavioural study on the long-

tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) in the residence of

west country, Bangi. M.Sc. Thesis, Universiti

Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia.

Thomas SC. 1991. Population densities and patterns of

habitat use among anthropoid primates of the Ituri forest,

Zaire. Biotropica. 23(1): 68-83.

Tikader BK and Das AK. 1985. Glimpses of Animal

Life of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Zoological

Survey of India, Calcutta.

Tuan-Zaubidah BTH. 2003. Nuisance behaviour of

Macaca fascicularis at Bukit Lagi, Kangar, Perlis. B.Sc.

Thesis, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi,

Selangor, Malaysia.

Rajeshkumar et al., 2014

Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347 1346

Umapathy G, Mewa Singh and Mohnot SM. 2003.

Status and Distribution of Macaca fascicularis umbrosa

in the Nicobar Islands, India. International Journal of

Primatology. 24(2): 281-293.

Van Noordwijk MA and van Schaik CP. 1999. The

effects of dominance rank and group size on female

lifetime reproductive success in wild long-tailed

macaques, Macaca fascicularis. Primates. 40(1): 105-

130.

Wheatley BP. 1980. Feeding and Ranging of East

Bornean Macaca fascicularis. In: The Macaques: Studies

in Ecology, Behaviour and Evolution, Lindburg, D.G.

(Ed.). Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York. 215-246.

Zamzarina MA. 2003. A study on aggressive

behavioural in Macaca at taman tasik taiping, perak,

B.Sc. Thesis, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi,

Selangor, Malaysia.

Rajeshkumar et al., 2014

Submit your articles online at www.jresearchbiology.com

Advantages

Easy online submission

Complete Peer review

Affordable Charges

Quick processing

Extensive indexing

You retain your copyright

submit@jresearchbiology.com

www.jresearchbiology.com/Submit.php.

1347 Journal of Research in Biology (2014) 4(4): 1338-1347

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Snorks Udl Lesson Plan-1Dokument4 SeitenSnorks Udl Lesson Plan-1api-253110466Noch keine Bewertungen

- GNM German New Medicine OverviewDokument6 SeitenGNM German New Medicine OverviewHoria Teodor Costan100% (2)

- Environmental Toxicology and Toxicogenomics 2021Dokument360 SeitenEnvironmental Toxicology and Toxicogenomics 2021ancuta.lupaescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chemical and Sensory Evaluation of Tofu From Soymilk Using Salting-Out MethodsDokument8 SeitenChemical and Sensory Evaluation of Tofu From Soymilk Using Salting-Out MethodsresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Random Control of Smart Home Energy Management System Equipped With Solar Battery and Array Using Dynamic ProgrammingDokument8 SeitenRandom Control of Smart Home Energy Management System Equipped With Solar Battery and Array Using Dynamic ProgrammingresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isolation and Characterization of Vibrio SP From Semi Processed ShrimpDokument8 SeitenIsolation and Characterization of Vibrio SP From Semi Processed ShrimpresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exploring The Effectiveness Level of Environment - Assistant Project On Environmental Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior of Primary School Students in The City of BehbahanDokument9 SeitenExploring The Effectiveness Level of Environment - Assistant Project On Environmental Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior of Primary School Students in The City of BehbahanresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antiparasitic Activity of Alstonia Boonei de Wild. (Apocynaceae) Against Toxoplasma Gondii Along With Its Cellular and Acute ToxicityDokument8 SeitenAntiparasitic Activity of Alstonia Boonei de Wild. (Apocynaceae) Against Toxoplasma Gondii Along With Its Cellular and Acute ToxicityresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seasonal Variation in The Benthic Fauna of Krishnagiri Reservoir, TamilnaduDokument5 SeitenSeasonal Variation in The Benthic Fauna of Krishnagiri Reservoir, TamilnaduresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Identification of Dust Storm Sources Area Using Ackerman Index in Kermanshah Province, IranDokument10 SeitenIdentification of Dust Storm Sources Area Using Ackerman Index in Kermanshah Province, IranresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reproductive Potential of Algerian She-Camel For Meat Production - A Case of The Region of SoufDokument6 SeitenReproductive Potential of Algerian She-Camel For Meat Production - A Case of The Region of SoufresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physicochemical, Phytochemical and Antioxidant Studies On Leaf Extracts of Mallotus Tetracoccus (Roxb.) KurzDokument11 SeitenPhysicochemical, Phytochemical and Antioxidant Studies On Leaf Extracts of Mallotus Tetracoccus (Roxb.) KurzresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Pressure On The Denaturation of Whey Antibacterial ProteinsDokument9 SeitenEffect of Pressure On The Denaturation of Whey Antibacterial ProteinsresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prunus Persica Compressa Persica Vulgaris Prunus Persica NucipersicaDokument7 SeitenPrunus Persica Compressa Persica Vulgaris Prunus Persica NucipersicaresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation of Natural Regeneration of Prunus Africana (Hook. F.) Kalkman in The Operating Sites of The Province of North Kivu at The Democratic Republic of CongoDokument8 SeitenEvaluation of Natural Regeneration of Prunus Africana (Hook. F.) Kalkman in The Operating Sites of The Province of North Kivu at The Democratic Republic of CongoresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Investigation of Volatile Organic Pollutants in Atmospheric Air in Tehran and Acetylene Pollutants in Tehran Qanat WatersDokument7 SeitenInvestigation of Volatile Organic Pollutants in Atmospheric Air in Tehran and Acetylene Pollutants in Tehran Qanat WatersresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Research in BiologyDokument8 SeitenJournal of Research in BiologyresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simulation of The Water Behaviour at The Karaj Dam Break Using Numerical Methods in GIS EnvironmentDokument9 SeitenSimulation of The Water Behaviour at The Karaj Dam Break Using Numerical Methods in GIS EnvironmentresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effect of Aggregates Stability and Physico-Chemical Properties of Gullies' Soil: A Case Study of Ghori-Chai Watershed in The Ardabil Province, IranDokument13 SeitenThe Effect of Aggregates Stability and Physico-Chemical Properties of Gullies' Soil: A Case Study of Ghori-Chai Watershed in The Ardabil Province, IranresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seasonal Patterns of Myxobolus (Myxozoa: Myxosporea) Infections in Barbus Callipterus Boulenger, 1907 (Cyprinidae) at Adamawa - CameroonDokument12 SeitenSeasonal Patterns of Myxobolus (Myxozoa: Myxosporea) Infections in Barbus Callipterus Boulenger, 1907 (Cyprinidae) at Adamawa - CameroonresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluating The Effectiveness of Anger Management Training On Social Skills of Children With Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)Dokument9 SeitenEvaluating The Effectiveness of Anger Management Training On Social Skills of Children With Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)researchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Improving The Emission Rates of CO, NO, NO2 and SO2, The Gaseous Contaminants, and Suggesting Executive Solutions For Accessing Standard Qualifications - A Case Study of Bandar Emam KhomeiniDokument10 SeitenImproving The Emission Rates of CO, NO, NO2 and SO2, The Gaseous Contaminants, and Suggesting Executive Solutions For Accessing Standard Qualifications - A Case Study of Bandar Emam KhomeiniresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Silico, Structural, Electronic and Magnetic Properties of Colloidal Magnetic Nanoparticle Cd14FeSe15Dokument6 SeitenIn Silico, Structural, Electronic and Magnetic Properties of Colloidal Magnetic Nanoparticle Cd14FeSe15researchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feasibility Study of Different Methods of Energy Extraction From Ardabil Urban WasteDokument14 SeitenFeasibility Study of Different Methods of Energy Extraction From Ardabil Urban WasteresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Feeding Fermented/non-Fermented Kapok (Ceiba Pentandra) Seed Cake As Replacements For Groundnut Cake On Performance and Haematological Profile of Broiler Finisher ChickensDokument7 SeitenEffect of Feeding Fermented/non-Fermented Kapok (Ceiba Pentandra) Seed Cake As Replacements For Groundnut Cake On Performance and Haematological Profile of Broiler Finisher ChickensresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Sunflower Extract To Control WeedsDokument8 SeitenEffect of Sunflower Extract To Control WeedsresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Examining The Effective Factors On Mistrust Towards Organizational Change and Relationship of These Factors With Organizational Health (Personnel of Sina, Shariati, and Imam Khomeini Hospital)Dokument10 SeitenExamining The Effective Factors On Mistrust Towards Organizational Change and Relationship of These Factors With Organizational Health (Personnel of Sina, Shariati, and Imam Khomeini Hospital)researchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Research in BiologyDokument1 SeiteJournal of Research in BiologyresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Evaluation of Different Energy Sources in Broiler DietsDokument5 SeitenComparative Evaluation of Different Energy Sources in Broiler DietsresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- TOC Alerts Journal of Research in Biology Volume 4 Issue 4 PDFDokument41 SeitenTOC Alerts Journal of Research in Biology Volume 4 Issue 4 PDFresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Survey of The Consumption of Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus and Abelmoschus Caillei) in A Population of Young People in Côte D'ivoireDokument7 SeitenSurvey of The Consumption of Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus and Abelmoschus Caillei) in A Population of Young People in Côte D'ivoireresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Examining The Effect of Physical, Chemical and Biological Harmful Factors On MinersDokument8 SeitenExamining The Effect of Physical, Chemical and Biological Harmful Factors On MinersresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Vitamins On Digestive Enzyme Activities and Growth Performance of Striped Murrel Channa StriatusDokument9 SeitenEffect of Vitamins On Digestive Enzyme Activities and Growth Performance of Striped Murrel Channa StriatusresearchinbiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artificial Neural Networks For Secondary Structure PredictionDokument21 SeitenArtificial Neural Networks For Secondary Structure PredictionKenen BhandhaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Field Survey ReportDokument24 SeitenField Survey ReportPranob Barua TurzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formulation and Evaluation of Moxifloxacin Loaded Alginate Chitosan NanoparticlesDokument5 SeitenFormulation and Evaluation of Moxifloxacin Loaded Alginate Chitosan NanoparticlesSriram NagarajanNoch keine Bewertungen

- English 2 Class 02Dokument23 SeitenEnglish 2 Class 02Bill YohanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- COVID-19 Highlights, Evaluation, and TreatmentDokument23 SeitenCOVID-19 Highlights, Evaluation, and TreatmentCatchuela, JoannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attitude, Personality, PerceptionDokument36 SeitenAttitude, Personality, PerceptionHappiness GroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- MlistDokument13 SeitenMlistSumanth MopideviNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Methods in Molecular Medicine) S. Moira Brown, Alasdair R. MacLean - Herpes Simplex Virus Protocols (1998, Humana Press)Dokument406 Seiten(Methods in Molecular Medicine) S. Moira Brown, Alasdair R. MacLean - Herpes Simplex Virus Protocols (1998, Humana Press)Rares TautNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reproduction and Embryonic Development in Plants and AnimalsDokument3 SeitenReproduction and Embryonic Development in Plants and AnimalsJoy BoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vitamin D in Hashimoto's Thyroiditis and Its Relationship With Thyroid Function and Inflammatory StatusDokument9 SeitenVitamin D in Hashimoto's Thyroiditis and Its Relationship With Thyroid Function and Inflammatory StatusMedicina UNIDEP T3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Modules 7 12 HistopathologyDokument9 SeitenModules 7 12 HistopathologyKrystelle Anne PenaflorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sphaerica and Oscillatoria AgardhiiDokument17 SeitenSphaerica and Oscillatoria AgardhiiMhemeydha Luphe YudhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Bank For Friedland Relyea Environmental Science For APDokument13 SeitenTest Bank For Friedland Relyea Environmental Science For APFrances WhiteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Immunology Mid-ExamDokument11 SeitenImmunology Mid-ExamNgMinhHaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary Immunodeficiency in ChildrenDokument16 SeitenSecondary Immunodeficiency in Childrenryan20eNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology - Test - Series - Chapter WiseDokument7 SeitenAnthropology - Test - Series - Chapter Wisedhivya sankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anisakis SPDokument15 SeitenAnisakis SPLuis AngelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dna ForensicsDokument40 SeitenDna ForensicsMaybel NievaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quirino State University Self-Paced Module on Genetic Trait ModificationsDokument5 SeitenQuirino State University Self-Paced Module on Genetic Trait ModificationsNel McMahon Dela PeñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BBA ClinicalDokument7 SeitenBBA ClinicalAyus diningsihNoch keine Bewertungen

- Papyrus: The Paper Plant ... Oldest Paper in HistoryDokument7 SeitenPapyrus: The Paper Plant ... Oldest Paper in Historynoura_86Noch keine Bewertungen

- Human Races and Racial ClassificationDokument6 SeitenHuman Races and Racial ClassificationanujNoch keine Bewertungen

- Happ Chapter 8 TransesDokument13 SeitenHapp Chapter 8 TransesFrencess Kaye SimonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar Isi Ebook Farmasi IndustriDokument25 SeitenDaftar Isi Ebook Farmasi Industriitung23Noch keine Bewertungen

- ANRS GradeEI V1 en 2008Dokument10 SeitenANRS GradeEI V1 en 2008Ibowl DeeWeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning Activity Sheet: SUBJECT: Earth and Life Science Mastery Test For Quarter 2 - Week 1&2Dokument1 SeiteLearning Activity Sheet: SUBJECT: Earth and Life Science Mastery Test For Quarter 2 - Week 1&2Kiara Ash BeethovenNoch keine Bewertungen

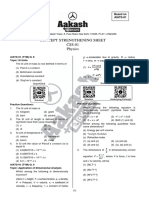

- Concept Strengthening Sheet (CSS-01) Based On AIATS-01 RMDokument19 SeitenConcept Strengthening Sheet (CSS-01) Based On AIATS-01 RMB54 Saanvi SinghNoch keine Bewertungen