Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Waldron On Dworkin

Hochgeladen von

DaidalOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Waldron On Dworkin

Hochgeladen von

DaidalCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

PUBLIC LAW & LEGAL THEORY RESEARCH PAPER SERIES

WORKING PAPER NO. 13-39

Ronald Dworkin: An Appreciation

Jeremy Waldron

J uly 2013

1

Ronald Dworkin memorial JEREMY WALDRON

St Johns, Smith Square, London

Wednesday, June 5, 2013

I do not envy those who have had to put into words today the loss of

Ronald Dworkin as a father or a friend. I have the easier task of

conveying a sense of the importance of his philosophical thought,

particularly in the philosophy of law.

I want to acknowledge what we have lost, from his being no

longer among us; but also I want to affirm what we gainedat

Oxford, in London, in New York, in the worldfrom his voice and

from the light of his intellect.

What we have not lost Well, we still have the booksTaking

Rights Seriously, a collection of papers that in 1977 transformed our

understanding of rights and right answers; Laws Empire, a decade

later, a powerful argument about interpretation and integrity; then

in 2011, the great synthesis, Justice for Hedgehogs, an affirmation of

the unity of value, bringing into a single Dworkinian vision an ethic

of dignity and a comprehensive legal and political theory.

What these books embodyand I have named only three out of

the fifteen or so that grace the Dworkinian bookshelfwhat these

books embody in jurisprudence is the most thoughtful and lucid

alternative to legal positivism that we have had in the modern era.

2

I dont mean anti-positivism, as though Ronnies aim was just

to refute the claims of his teachers at Oxford. His work may have

started that way 45 years ago, in The Model of Rules. But in fact

what has been most valuable in Ronnies jurisprudential thought is

the elaboration of an alternative theory of law,which, mostly, was

allowed to develop under its own elegant momentum.

In this great and graceful body of work, Ronnie gave us a living

jurisprudence, one which credited the practice of law with reason

and thoughtfulness, not just the mechanical application of rules. It

was a jurisprudence that taught us to take seriously forms of

argument thatto the bewilderment of positivists, pragmatists, and

all sorts of skepticshave lawyers and judges delving doggedly

again and again into the books of the law to search for legal answers

to hard cases, rather than just admitting defeat at the first sign that

there is not going to be any text or precedent directly on point.

He had the effrontery to suggest that there were right answers

to the legal problems posed in hard cases and that it mattered

whether we got the answers right or wrong. This was a view which

many disparaged, but it was a view that respected the position of

plaintiffs and petitioners as people coming into law to seek

vindication of their rights, not just as lobbyists for a quasi-legislative

solution. It was a position, too, that respected the obligation of

3

judges never to give up on the sense that the existing law demanded

something of them, even in the most difficult disputes.

Under the Rule of Law, we dont just settle points of law

pragmatically. We proceed, as far as possible, in a way that keeps

faith with what is already laid down.

Dworkin helped us chart the topography of law; for the corpus

juris is not just a heap of norms; beneath the explicit rules there are

principles and policies that a legal system has committed itself to

implicitly, over the years; deep subterranean channels of moral

concern that flow through every part of the law.

In an argument of quite stunning complexity, his 1986 book

Laws Empire set out grounds for the responsibility that lawyers and

judges have to the laws as a whole, including their responsibility to

measures enacted by people who may not have shared their views

about justice. Our job, he said, as lawyers, scholars, and judges, is to

bring interpretive coherenceintegrityto the whole body of the

law.

The unearthing of these principles and the burden of this

integrity meant that legal reasoning, in Ronnies opinion, is a form of

moral reasoning. This was the artery of his jurisprudence: that legal

reasoning is a form of moral reasoning. Certainly, it is a complicated

and uneasy form, for it depends on judgments about the moral

4

importance of contingent events like enactment and the setting of

precedents that ordinary moralizing does not concern itself with.

Nothing guarantees that our laws will be just, Ronnie

acknowledged. But that doesnt mean that we separate the relation

between law and morality; it means we complicate the relation

between law and morality. Like a system of ethics that has to deal

with the moral significance of promises we wish had never been

made, so too the morality of law has to come to termscome to

moral termswith statutes we wish had never been passed and

precedents we wish had not been laid down. But the mark of

legality is the felt need to respect those with whom we share the

community, including those whose decisions we disagree withto

respect on moral grounds the legacy that they have contributed to,

as we expect them to respect the legacythe same legacy of law

that we have contributed to.

As I said, the affirmation of this entanglement of law and

morality was the artery of Ronnies jurisprudence. And for the

philosophy of law generally, these are ideas of momentous

importance. They will resonate down the generations. They are not

uncontroversial by any means, but the controversies they provoke

have been productive, sparklingly productive, in the otherwise

desiccated landscape of our subject.

5

It is not just legal philosophy. No one can do justice in ten short

minutes to thought as wide-ranging as Ronnies. There is his work

in constitutional law: what he called the moral reading of the

American constitution; and his conviction that even in Britain, a bill

of rights with strong judicial review was not only possible, but

would strengthen democracy by strengthening the conditions that

make democracy legitimate.

Then there is his writing on equality in moral and political

philosophy, which he began working on at the end of the 1970s

producing two articles of massive importance in the first ever issues

of Philosophy and Public Affairs. Like many here today, I had the

good fortune to attend the seminars on these and other topics

where Ronnie stood with other titans like Bernard Williams, Charles

Taylor, Amartya Sen, and Derek Parfit. (Those were the days when

lectures and seminars at Oxford were something more than just

adjuncts to courses.) It is impossible to overestimate the influence

of these pieces on equalityWhat is Equality? 1. Equality of

Welfare and What is Equality? 2. Equality of Resources in

setting the agenda for the study of justiceluck egalitarianism and

so onin the 1980s, 1990s and beyond.

We marveled then at the range of Dworkins ideas. We thought

he was a glamorous fox who knew ever so many things. We didnt

6

always see that, while he was working both on the theory of equality

and on the jurisprudence of Laws Empire and on the substance of

end-of-life and abortion issues in Lifes Dominion, he was also laying

the foundations for a unifying ethical vision that, in the manner of

the hedgehog, would bring together these different facets of a

comprehensive theory of justice.

The vision was unified, in his great ethical work, Justice for

Hedgehogs, by a principle of dignity. Each person, said Ronnie, has a

certain responsibility for the precious shape of his or her own life,

and everyone has a duty to respect the conditions under which

others are able to discharge that responsibility. Thats what human

dignity meant for Ronnie and it underpinned both the principles of

responsibility that were so important in the luck-egalitarian side of

his account of equality and the principles of mutual respect that are

represented in the rule of law. His great work of synthesis, Justice

for Hedgehogs revealed this as the foundation of all his positions

and I do mean foundation, which is not the same as the

fortification that allows a philosopher to see off contrary intuitions.

I mean that Justice for Hedgehogs bravely identified the very deep

underpinning of his various positions, even though that explicit

identification made each of them somewhat more vulnerable, by

presenting a deeper as well as a wider and more integrated target.

7

*

I talked at the beginning about what we have lost and what, through

Ronnies life and work, we gained. What we have and can treasure

still are the writings, the books, the articles (whether they are in the

Oxford Journal of Legal Studies or the New York Review of Books), the

jurisprudence, the new ways of connecting ethics and political

philosophy.

What we have lost, though, is what you have heard about from

others this afternoon: the warmth of his chortling good humor, the

liberality of his positions and personality; his generous and

embracing charm; the strength of a mind that could sustain an

argument in a lecture for 90 minutes without a note, the dogged and

delighted commitment to intellectual exchangeRonnie was never

one to allow himself the last word in an argument and he wouldnt

allow anyone else the last word either.

I had the honor to engage him for years in arguments about

judicial reviewa disagreement that has loomed large in the

pleasure and profit of exchange, but that is dwarfed by everything I

owe to him in the example he set of a commitment to the sunny

upland expansiveness of political philosophy pursued in the

radiance of an affection for the law.

8

I have tried to be calm in what Ive said this afternoon about

Ronnies thought and legacy. But it is very difficult. This is not just a

tribute; it is a love letter, to a man who 35 years ago at Oxford

helped me find my feet, who over the years set forth for me the

virtue of argument through his own good-humored example, who

showed meshowed us allhow much more you can achieve by

taking seriously the nobility of laws empire than by any corrosive

or skeptical detachment from its aspirations.

To his memory, then, I pledge a resolve, as far as I am able, to

carry this on, with others I hope, to continue the refreshment of

jurisprudence with these insights Ronnie gave us, in a way that does

justice to the generosity and unity of his vision.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Two Sides of Effective Oral CommunicationDokument17 SeitenTwo Sides of Effective Oral CommunicationSharath KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opening RitualDokument17 SeitenOpening RitualTracy CrockettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Larsen ManineaDokument5 SeitenLarsen ManineaDaidalNoch keine Bewertungen

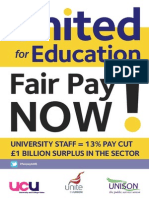

- Hedispute13 StrikeA4leaflet UniteDokument2 SeitenHedispute13 StrikeA4leaflet UniteDaidalNoch keine Bewertungen

- HEFCE Consultation On Future REFSDokument8 SeitenHEFCE Consultation On Future REFSDaidalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ucu Openaccess Campaignbriefing Nov13 PDFDokument6 SeitenUcu Openaccess Campaignbriefing Nov13 PDFDaidalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bertelli A Carnes I 2Dokument3 SeitenBertelli A Carnes I 2DaidalNoch keine Bewertungen

- SyllabusDokument370 SeitenSyllabusDaidalNoch keine Bewertungen

- HE Dispute 2013 - United For Education FlyerDokument2 SeitenHE Dispute 2013 - United For Education FlyerpastetableNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contracts-Nature and TerminologyDokument19 SeitenContracts-Nature and TerminologyNguyễn Trần HoàngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perceptiual - Cognitive SkillDokument17 SeitenPerceptiual - Cognitive SkillGeovani AkbarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wildlife Ecology - Unit 14 - Week (12) - RevisionDokument1 SeiteWildlife Ecology - Unit 14 - Week (12) - RevisionAdityaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (PC) Brian Barlow v. California Dept. of Corrections Et Al - Document No. 4Dokument2 Seiten(PC) Brian Barlow v. California Dept. of Corrections Et Al - Document No. 4Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPE-21639-MSDokument8 SeitenSPE-21639-MSehsanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mugunthan ResumeDokument4 SeitenMugunthan Resumeapi-20007381Noch keine Bewertungen

- Richard Payne v. Scottie Burns, Sheriff Escambia County, J.B. Redman, LT., and Cecil White, Officer, 707 F.2d 1302, 11th Cir. (1983)Dokument2 SeitenRichard Payne v. Scottie Burns, Sheriff Escambia County, J.B. Redman, LT., and Cecil White, Officer, 707 F.2d 1302, 11th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Six Sigma: Everything You Need To Know About It: by Pankaj KumarDokument16 SeitenWhat Is Six Sigma: Everything You Need To Know About It: by Pankaj KumarSuman DewanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning Competencies For English - Grades 11-12Dokument5 SeitenLearning Competencies For English - Grades 11-12Neo Artajo100% (1)

- MRI BRAIN FINAL DR Shamol PDFDokument306 SeitenMRI BRAIN FINAL DR Shamol PDFDrSunil Kumar DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- FluteDokument3 SeitenFlutepatrickduka123100% (1)

- 58 58 International Marketing Chapter WiseDokument126 Seiten58 58 International Marketing Chapter WiseNitish BhaskarNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Multivocal Literature Review of Decentralized Finance: Current Knowledge and Future Research AvenuesDokument37 SeitenA Multivocal Literature Review of Decentralized Finance: Current Knowledge and Future Research Avenuesnofeh84660Noch keine Bewertungen

- Christoffel Symbols: PHYS 471: Introduction To Relativity and CosmologyDokument9 SeitenChristoffel Symbols: PHYS 471: Introduction To Relativity and Cosmologyarileo3100% (1)

- Assessing The NeckDokument3 SeitenAssessing The NeckAnne Joyce Lara AlbiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Casalla vs. PeopleDokument2 SeitenCasalla vs. PeopleJoan Eunise FernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- NIH Strategic Plan For Data ScienceDokument26 SeitenNIH Strategic Plan For Data ScienceAristide AhonzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Download Cosmetic Injection Techniques A Text and Video Guide To Neurotoxins Fillers Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full ChapterDokument36 SeitenHow To Download Cosmetic Injection Techniques A Text and Video Guide To Neurotoxins Fillers Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full Chapterkerri.kite140100% (23)

- Significance of Research in Education - Research ArticleDokument18 SeitenSignificance of Research in Education - Research ArticleSalex E. AliboghaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advertisement On Sunflowers Perfume by Elizabeth ArdenDokument18 SeitenAdvertisement On Sunflowers Perfume by Elizabeth ArdenNur Fajarwati ZuchrifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital StructureDokument59 SeitenCapital StructureRajendra MeenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The CIA Tavistock Institute and The GlobalDokument34 SeitenThe CIA Tavistock Institute and The GlobalAnton Crellen100% (4)

- ARIMA Models in Python Chapter3Dokument52 SeitenARIMA Models in Python Chapter3FgpeqwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sources of Coherent RadiationDokument7 SeitenSources of Coherent RadiationSubhash DhungelNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Summer's Reading - Sample Questions With AnswersDokument11 SeitenA Summer's Reading - Sample Questions With AnswersRoy SchwartzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dilo SpaDokument2 SeitenDilo SpajosefNoch keine Bewertungen

- CS3C Mover Practice 2Dokument4 SeitenCS3C Mover Practice 2Nguyễn Lê Hà ViNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antenna & Wave Propagation - Course OutlineDokument2 SeitenAntenna & Wave Propagation - Course OutlineSabuj AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen