Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

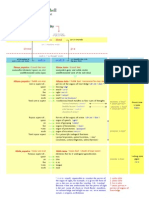

Explanation of Avatara - Excerpt From Pujya Swamiji's BGHS, Ch4

Hochgeladen von

Prashānt ParikhOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Explanation of Avatara - Excerpt From Pujya Swamiji's BGHS, Ch4

Hochgeladen von

Prashānt ParikhCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chapter 4

Isvara, Krsna can say, as he did here 'Keeping My maya under My control, I become

one who as though has a body.' This is the definition of an avatara.

When it is said that an avatara is one who comes down, what is meant is that he

assumes a body. He 'as though' has a lody, 'as though' because he is not lost in the

body - in other words, he does not take himself to be the body. Ajivanmukta, one who

is liberated, can also say, 'I 'as though' have a body,' because this person knows the real

nature of 'I,' the atmd. To be able to say this requires knowledge and, to acquire this

knowledge one has to be living. This is why the person who has such knowledge is

calledjivanmukta - living, he is liberated. And, before this knowledge takes place, the

jiva comes into this world as a result of the past karma alone.

By the force of karma, meaning one's past actions and their results, a physical

body, along with a mind and senses, is created with a parentage and a time and place,

and we say the person is born. Such a person is called jiva. Only by acquiring the

knowledge that he or she is param brahma can the jva be free of the cycle of birt and

death and all that goes with it. Knowing thus, the person is free, but the body contnues

to exist, because it is the creation of Isvara - ivara-srsti.

OMNISCIENCE DOES NOT REQUIRE A MIND

Thus, Krsna tells Arjuna here that, as Isvara, he keeps the maya under his

control. His powers, the jifna-gakti, the power to know, the kriya-gakti, the power to

do, and the iccha-gakti, the power to desire, are all under his control and are not limited

in any way. Since his power to know is without limitation, he does not require an antah-

karana, a mind, to know. Without the mind, he has all knowledge. All-knowledge,

omniscience, cannot depend upon a given mind because any mind will have some

limitation. Furthermore, the mind itself is a creation and, before creating it, the Lord

must have knowledge. Therefore, no mi d is required by Isvara. The very maya itself

makes him omniscient. He is called Paramnedvara and this ParameSvara alone becomes

the world. This is the maya, the trick of it all.

AN UNDERSTANDING OF AVATARA

In order to understand the Vedic apd Purdnic literature, one needs to have some

understanding of the concept of avatara. In the BhSgavata, Rdmayana, and the

Mahdbhdrata, Rama, Krsna and certain others are presented as avataras. 'Ava dra'

means 'God incarnate.' Because of its significance here, this concept will be analysed

briefly in terms of orders of reality.

In general, we can divide the orders of reality into three. One is the absplute

reality, pdramarthika, that which is satya-jiidna-ananta-brahma, free fror all

attributes, and upon which the entire world depends. Then there is the empirical reality,

vyavahdrika, which accounts for the world and all that is in it, space, air, fire, Water,

Bhagavadglta

earth, the sun, moon, and stars, the natural laws, and so on. Included in this order of

reality are the various situations that cause joy and sorrow, as well as your physical

body, mind, and senses. All means and ends - sadhana and sadhya, also have an

empirical reality, some of which are already known to you and others are revealed by the

Veda. There are certain Vedic rituals, for example, that are prescribed for having a child

or for going to heaven. The heaven mentioned by the astra is considered to be as

empirically real as a material object here in this world. Thirdly, there is a purely

subjective order of reality, pratibhasika, such as that we experience in a dream.

EMPIRICAL REALITY

A pot, for instance, is not something that you imagine; it actually holds water. But

it cannot be considered to be independently real, absolutely real, because it is dependent

on something else for its existence - the material out of which it is made. Therefore,

you cannot say it is paramarthika-satya. Nor can you dismiss it as non-existent because

it holds water! If you say the pot is absolutely real or that it is absolutely non-existent,

your very statement does not hold water. Only an existent pot can hold water, a non-

existent pot cannot.

The existent pot is something that has a history. It was born at a given time and has

lived in various homes. It has gone through a certain process of growth and old age,

holes and repair work. It has seen ages and has passed through many hands. Now, having

had its day, it is parked in some corner somewhere, an old useless pot. Thus, the pot

definitely enjoys a certain reality, because of which we accept it as something that has a

name and form, nama-ripa, and behaves within certain laws. This reality is what is

meant by empirical reality, vydvaharika-satya. And, for understanding the empirical

reality, we have sense perception and other pramanas such as inference and

presumption.

When the Veda talks about ends like heaven and the means for attaining them, it is

talking only about empirical reality. If heaven is a place, it is something within the

creation and, therefore, is included in this order of reality. The various rituals enjoined

by Veda imply a doer, karta, who must perform certain karmas in order to achieve the

desired ends. Since the means and end are interconnected, the means also have an

empiricality, whether they involve worldly action, laukika-karma, or scriptural

injunction, vaidika-karma. Because means and ends are all dependent upon something

else, they are not absolutely real. Therefore, they are not paramarthika, but

vyavaharika, being totally within the empirical sphere.

The word 'empirical' is the closest English translation there is for vydvahSrika,

which covers everything known and unknown within the sphere of the creation that is

not created by a given mind. It includes everything that is understood at a given time. It

also includes all that is not understood now but that may be understood later. This kind

Chapter 4

of world and the mind itself - the mind Stuff, brain cells, and so on - all belong tp the

empirical world. The physical body and its organs, the senses and their constituents, the

capacity to remember, to love, to think, and to know, are all vydvaharika, meaning that

they have an empirical reality.

SUBJECTIVE REALITY

The third order of reality is purely subjective and is called pratibhasika in

Sanskrit. The dream is an example of this order of reality. Something exists because you

see it. Any mistaken notion, unknown fears, and all forms of projections are also

pratibhasika. When, for instance, you take a post for a man, (sthanau purusa-

dargana) or imagine that some one does not like you, it is a projection - purely

subjective and therefore, pratibhasika. What you see is not there; but still you see it.

The very seeing gives your projection a certain reality.

Everyone projects; everyone commits mistakes. Pratibhasika reality is possible

because the mind is limited; it is not omniscient. Also, the mind has a particular

background that creates for itself certai1 prejudices, fears, anxieties, disappointments,

sorrows, and perceptions. This is why everyone, at one time or another, sees what i not

really there and does not see what is there,

For example, even though a person has some love for you, you may not reconise

it, seeing instead some dislike, simply bedause you happen to notice the person frowning

and you know not why! All projections, all mistakes, are possible because you have a

mind. You think so and therefore, it is. And since this reality that exists only for you has

no empiricality, it is called pratibhasika.

Wherever there is pratibhasika reality, there is error and, wherever there is error,

the correction of error must be possible, hat is, knowledge must be there. Suppose, for

example, you are making pastry and mistake the salt for sugar. What you want is pastry,

but what you get is something quite different. Both the sugar and the salt hav an

empirical reality because the senses are able to differentiate between them. At the same

time, there is a mistake because sugar produces pastry and salt produces something else.

If you use salt thinking it will make pastry, you are committing a mistake. Given this

particular fact, this law, error is always possible.

This is all within our experience. Atmd is the self-evident experience.

Consciousness is experience. All experiences are strung into this consciousness by this

consciousness, just as beads are held together by a string. Consciousness is there it all

the three forms of experience - sleep, dream and waking. These three experiences,

severally and totally, are held in one experience called consciousness, which is all-

evident.

Bhagavadgita

It is evident that we create our own subjective realities and it is also evident that

we are dealing with a world which conforms to an order, which behaves in an orderly

way. Thus, we have a cosmos which is empirical, a chaos which is subjective, and that

which is constant, sat-cit-dnanda-atma. This sat-cit-ananda-atma seems to exist in the

form of a three-fold reality. For lack of a better term, we use this term, viz., the three-

fold reality. In fact, there is only one reality, satya-jiina-ananta-brahma.

THE RELATIONSHIP AMONG THE THREE ORDERS OF REALITY

Between the empirical reality and the subjective reality, there is a difference. The

entire creation, empirical reality, is called isvara-srsti, the Lord's creation, and the

projection of one's own mind is called jva-srsti, the individual's subjective creation. At

all times, we are confronting these two orders of reality, the empirical and the subjective,

on the basis of the one absolute reality, satya-jhiana-ananta-brahma.

With this understanding of the orders of reality, let us return to the verse. Krsna

says, 'I am born wielding the mdya, the prakrti, in My hands. In this way, I assume a

body.' Because the Lord can create the whole world and also assume a body, there is no

problem in seeing that Krsna's birth is referred to here as an incarnation of 19vara based

on the concept of avatdra, avatara-vada. But the next question would be, 'To which

order of reality does the physical body that the Lord assumes belong?'

When Krsna points out that he is unborn, never born, he is pointing out the

absolute reality, pdramdrthika-satya. In fact, from the standpoint of absolute reality, no

one is born. Thus, from this standpoint, Krsna is not born and Mr. Krsna, who is

standing before Arjuna, cannot be that paramarthika-satya. It must be kept in mind

here that we are not talking about Krsna who is paramatma; but we are talking about

Mr. Krsna who was born in prison, who had a body, who wore a yellow piece of cloth,

who played a flute, and who, seated in Arjuna's chariot, was holding the reins of the

horses in his hands. Is this Krsna, who was teaching Arjuna, pdramdrthika? No, he is

not, because his body is not paramarthika.

Surely, then, we can say that Krsna's body is empirically real, vyavaharika. But

if it were to be taken as empirically real, would Krsna not have been born of his own

karma and therefore, would he not also be a samsarn like Arjuna? And if he were born

of his own karma, punya and pdpa would be there for him, along with dharma and

adharma, doership and enjoyership? If he were bound by karma, where would be the

possibility of his wielding the mdya? In order for his birth to be considered empirical,

Krsna had to have been under the spell of karma, meaning that without his volition his

birth would have been determined by the very laws. Only then can his birth be

considered to be like empirical that of Arjuna.

Chapter 4

THE EMPIRICAL REALITY OF A JIVA S BIRTH

Arjuna, being a jva, was born of karma. Even though he was born a pri ce, he

had to go to the forest for twelve years and then live incognito for one year, all of which

could be attributed to his past karia. The destiny of Arjuna's eldest brother,

Dharmaputra, was also controlled by his own punya and papa. Because of his papa,

he lost the kingdom; otherwise, the dice would have rolled out differently or he would

not have thrown them at all! Some prirabdha-karma was there for him. The adstra

itself talks about this kind of karma.

Arjuna was a person, a jva, born of karma and therefore, his birth, janma, was

empirically real. He had a parentage and a physical body, mind, and senses, all of which

have an empirical reality, as we have seen. Krsna, on the other hand, said that, as

Isvara, keeping the maya under his cqntrol, he is born. We will see later why le was

born.

THE REALITY OF KRSNA'S BIRTH

The body of anyone who is born is available for our perception. But vhat is

available for our perception is not always totally true - the blue sky, for example, or a

magician's tricks. Therefore, perception itself cannot establish the empirical reality of

Krsna's birth.

If, as isvara, Krsna is born, keeping the maya under his control, his birth is

definitely not subject to any punya or papa. Therefore, being not bound by karma, it

has no empirical status. Birth itself, beirg what it is, cannot be paramarthika either. Nor

can Krsna's birth be totally non-existent, atyanta-asat, since he was not a vandhyd-

putra, the son of a barren woman! He was born of Devaki and Vasudeva. Thus, it was

not a totally non-existent Krsna who was talking to Arjuna.

Then, how are we to explain Krsna's birth in terms of reality? With reference to

his birth, Krsna is prdtibhasika - you see him, therefore, he is. His birth is not due to

karma; it is only apparent. Pratibhasika means that there was a Krsna whom everyone

saw, but his birth and his body were purely maya. Like everything else, they were born

of maya but without the force of the law of karma. This kind of birth means that TIvara

is not condemned to the state ofjivatva. He merely assumes a particular body die to a

certain necessity alone.

WHY DOES ISVARA ASSUME A PHYSICAL BODY?

And what is it that makes it necessary for the Lord to assume a physical body? In

the purdnas it is said that before every incarnation there is a collective petition to the

Lord in the form of prayers on the part of all the good people and even the deias: '0

Lord, please do something! Please come and remedy this situation. It is time. Tine's up,

Bhagavadgita

in fact! Why haven't you come? The tyranny of these people is too much for us to bear,'

etc. These very prayers themselves become the material cause, the updadna-kdrana, for

the Lord to introduce himself in a particular form, meaning that he assumes a body.

The prayers of the fivas become the punya because of which a particular body is

born for a given purpose. This incarnation of the Lord is what is meant by avatdra. The

purpose of the avatdra's coming may be just to do one job, like Narasimha-avatara or

Vamana-avatara, or to do many, as was the case with Rama and Krsna. In addition to

the many jobs they came to do, Rama and Krsna also served as examples with reference

to how people should live their lives. Rama exemplified how one can live a life of

dharma in the face of all adversity and Krsna was an embodiment of joy and wisdom.

It should be clearly understood that the concept of avatara is not required at all in

order to worship Krsna as the Lord. A picture of Krsna as Isvara is all that is needed for

invoking the Lord. In fact, we can invoke the Lord in anything, even a rock. Invoking the

Lord in a particular form and the concept of avatdra are entirely different. We discuss it

here only because the verse is referring to Krsna as avatdra. Krsna himself says, 'By

my own powers of mdyd, I "as though" assume a body.' Sahkara says in his

commentary to this verse, while explaining how Isvara assumes a body, 'dehavdn iva,

jatah iva - as though with a body, as though born.' The word, 'iva - as though' in

Sankara's commentary indicates that there can be no empiricality here because Krsna's

birth was not out of punya and pdpa.

If there were punya and pdpa for Isvara, then he would not be Isvara at all!

Therefore, when Isvara assumes a body, he is only as though born. He has a body, but

his body has no empiricality because it was not born out of punya and pdpa. If there

were punya and pdpa for Isvara, we would have the problem of an Isvara with

limitations with reference to the antah-karana, which is not acceptable. And, as we

have seen, that is not possible, because Isvara is all-knowledge. Therefore, Krsna tells

Arjuna here, 'Without punya and pdpa, I am born,' which is the very concept of

avatara.

In the next verse, Krsna explains why, as Isvara, he assumes a body:

3zTrHp dzH WM^,l I \ I

yadd yadd hi dharmasya glanirbhavati bharata

abhyutthdnamadharmasya

taddtmdnam srjamyaham Verse 7

WlM bhdrata - 0 Descendent of the Bharatas! (Arjuna); ZiT ZT yadd yadd -

whenever; * hi - indeed; 4T4; dharmasya - of right living; *fT: glanih - decline;

3PT4 T adharmasya - of wrong living; 3PTtFrMT abhyutthanam - rise

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1091)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Books - The Cult of Divine Power - "Shaki Sadhana" (Kundalini Yoga) - SinhaDokument145 SeitenBooks - The Cult of Divine Power - "Shaki Sadhana" (Kundalini Yoga) - SinhaAlex Wolfers100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Patanjali Yoga Sutras TranslationDokument41 SeitenPatanjali Yoga Sutras TranslationPrashānt Parikh100% (4)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Robert Adams - A New Reality ExcerptDokument10 SeitenRobert Adams - A New Reality ExcerptAlcyoneSpiralNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Nandi KeshDokument11 SeitenNandi KeshpaseshanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SphotaDokument57 SeitenSphotaVikram BhaskaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annamalai Swami Meditation QuotesDokument4 SeitenAnnamalai Swami Meditation QuotesLXNDR1100% (1)

- BeejaaksharasDokument8 SeitenBeejaaksharasybbvvprasada raoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essence of Bhaagya-Bhogya-Yogyata LakshmiDokument265 SeitenEssence of Bhaagya-Bhogya-Yogyata LakshmiRajeevSangamNoch keine Bewertungen

- MUNDAKA UPANISHAD by Swamy ParamarthanandajiDokument343 SeitenMUNDAKA UPANISHAD by Swamy ParamarthanandajiPrashānt Parikh86% (14)

- Basic Tenets of Saiva Siddhanth AmDokument15 SeitenBasic Tenets of Saiva Siddhanth AmKrishnan Palaniappan100% (1)

- The Problem of Two Truths in Buddhism and VedantaDokument132 SeitenThe Problem of Two Truths in Buddhism and VedantahierophantnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Neo-Vedanta Philosophy of Swami VivekanandaDokument18 SeitenThe Neo-Vedanta Philosophy of Swami VivekanandaMarekVáchalNoch keine Bewertungen

- TattvaBodhaChart PDFDokument1 SeiteTattvaBodhaChart PDFsatya0988Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hillman Suicide and The SoulDokument10 SeitenHillman Suicide and The SoulRenzo Benvenuto100% (2)

- SD 2Dokument640 SeitenSD 2pabitra100% (1)

- Nath YogisDokument98 SeitenNath YogisB V Diwakar100% (1)

- Shimla Lecture II, 2012 Liberation From Passion Vs Liberation Through Passions - Raffaele TorellaDokument9 SeitenShimla Lecture II, 2012 Liberation From Passion Vs Liberation Through Passions - Raffaele Torellaraffaeletorella100% (1)

- TRALEG KYABGON - The-Influence-of-Yogacara-on-Mahamudra PDFDokument145 SeitenTRALEG KYABGON - The-Influence-of-Yogacara-on-Mahamudra PDFFilippo Lunardo100% (1)

- Avadhut-Gita - Hari Prasad ShastriDokument21 SeitenAvadhut-Gita - Hari Prasad ShastriKasturi KamathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tirumūlar's TirumandiramDokument13 SeitenTirumūlar's Tirumandiramshanmugam avadaiyappa100% (1)

- Sai Baba GitaDokument244 SeitenSai Baba Gitasathi2317411Noch keine Bewertungen

- Advaita Handbook by S.N. Sastri JiDokument76 SeitenAdvaita Handbook by S.N. Sastri JiPrashānt ParikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pujya Swami Dayananda-PancakamDokument1 SeitePujya Swami Dayananda-PancakamPrashānt ParikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Being A Student of Vedanta BedeDokument92 SeitenBeing A Student of Vedanta BedePrashānt ParikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- TarkasamgrahaDokument25 SeitenTarkasamgrahaKanchi SrinathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Am IDokument45 SeitenWho Am IPrashānt Parikh100% (1)

- Time in Hinduism, Harold Coward, 1999Dokument7 SeitenTime in Hinduism, Harold Coward, 1999Roque Lazcano VázquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sadhana ..0dfDokument20 SeitenSadhana ..0dfGur PreetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sankara 3 SinsDokument5 SeitenSankara 3 SinskauntinyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- VIDHATADokument81 SeitenVIDHATAMaanoj Rakhit / Yashodharma100% (1)

- Superman Notes On JainismDokument19 SeitenSuperman Notes On JainismRahul TripathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paramartha PrasangaDokument37 SeitenParamartha PrasangaRafaela MouraNoch keine Bewertungen

- BinduDokument11 SeitenBindumira003Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sri Guru and His Grace by Bhakti Raksak Srila Sridhar Dev-GoswamiDokument123 SeitenSri Guru and His Grace by Bhakti Raksak Srila Sridhar Dev-GoswamiAlexey GogolevNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life and Precepts of Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu PDFDokument34 SeitenLife and Precepts of Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu PDFAnilkumar ManukondaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TeacherDokument224 SeitenTeachersasimouli kambhampati100% (1)

- Dakshinamurthy StotramDokument12 SeitenDakshinamurthy Stotramnsprasad88100% (1)

- Mayavadi PhilosophyDokument21 SeitenMayavadi PhilosophydhvanibaniNoch keine Bewertungen