Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Class 5 - Digests Labor Relations 1: Miguel Case. The Provisions of The Code Clearly

Hochgeladen von

Rowena Gallego100%(1)100% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (1 Abstimmung)

673 Ansichten2 SeitenThe Supreme Court dismissed PAL's petition challenging a ruling requiring it to discuss revisions to its employee Code of Discipline with the employees' union PALEA. While management has broad authority over business operations, rules affecting employee rights like job security require transparency and discussion with the union. The Court found specific provisions of the revised Code implicated constitutional protections and could result in loss of livelihood. Moreover, achieving labor peace demands informing and involving workers in matters concerning their employment terms and conditions.

Originalbeschreibung:

labor relations - case digest

Originaltitel

PAL vs. NLRC & PALEA

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThe Supreme Court dismissed PAL's petition challenging a ruling requiring it to discuss revisions to its employee Code of Discipline with the employees' union PALEA. While management has broad authority over business operations, rules affecting employee rights like job security require transparency and discussion with the union. The Court found specific provisions of the revised Code implicated constitutional protections and could result in loss of livelihood. Moreover, achieving labor peace demands informing and involving workers in matters concerning their employment terms and conditions.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

100%(1)100% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (1 Abstimmung)

673 Ansichten2 SeitenClass 5 - Digests Labor Relations 1: Miguel Case. The Provisions of The Code Clearly

Hochgeladen von

Rowena GallegoThe Supreme Court dismissed PAL's petition challenging a ruling requiring it to discuss revisions to its employee Code of Discipline with the employees' union PALEA. While management has broad authority over business operations, rules affecting employee rights like job security require transparency and discussion with the union. The Court found specific provisions of the revised Code implicated constitutional protections and could result in loss of livelihood. Moreover, achieving labor peace demands informing and involving workers in matters concerning their employment terms and conditions.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 2

Class 5 - Digests Labor Relations 1

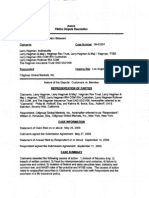

#1 PAL vs. NLRC & PALEA

G.R. No. 85985 / AUG. 13, 1993

J. MELO

FACTS:

The PAL completely revised its 1966 Code of

Discipline, afterwhich, was circulated among the

employees and was immediately implemented.

Some employees were forthwith subjected to the

disciplinary measures embodied therein.

Thus, the PALEA filed a complaint before the NLRC

for ULP. In its position paper, it contended that by

PALs unilateral implementation of the Code, it was

guilty of ULP. It also alleged that copies of the Code

were circulated in limited numbers; the Code, being

penal in nature, must conform with the requirements

of sufficient publication; and further alleged that the

Code was arbitrary, oppressive and prejudicial to the

rights of the employees. It prayed that the

implementation of the Code be held in abeyance;

that the PAL should discuss the substance of the

Code with PALEA; that the dismissed employees

under the Code be reinstated and their cases be

subjected to further hearing; and that PAL be

declared guilty of ULP and be ordered to pay

damages.

PAL on the other hand, filed a motion to dismiss the

complaint, asserting its prerogative as an employer

to prescribe rules and regulations regarding

employees conduct. In its Reply, PALEA maintained

that PAL violated Art. 249 (e) of Labor Code when it

unilaterally implemented the Code, and cited some

provisions of the Code as defective, for running

counter to the construction of penal laws and making

punishable any offense within PALs contemplation.

Upon failure of the parties to appear at the

scheduled conference, a decision was rendered by

the labor arbiter, finding no bad faith on the part of

PAL in adopting the Code and ruled that no ULP had

been committed. However, the arbiter held that

PAL was not totally fault free considering that

while the issuance of rules and regulations

governing conduct of employees is a legitimate

management prerogative, such rules and

regulations must meet the test of

reasonableness, propriety and fairness. It also

ordered PAL to discuss with PALEA the

objectionable provisions and to furnish all employees

with the new Code of Discipline.

PAL appealed to the NLRC which modify the

appealed decision in the sense that the New Code of

Discipline should be reviewed and discussed with

complainant union, particularly the disputed

provisions. Thereafter, PAL is directed to furnish

each employee with a copy of the appealed Code of

Discipline. The pending cases adverted to in the

appealed decision if still in the arbitral level, should

be reconsidered by PAL.

Hence, the filing of the instant petition for certiorari

by PAL.

ISSUE:

Whether or not the management may be compelled

to share with the union or its employees its

prerogative of formulating a code of discipline.

RULING:

YES, the exercise of managerial prerogatives

is not unlimited. It is circumscribed by limitations

found in law, a collective bargaining agreement, or

the general principles of fair play and justice

Moreover, it must be duly established that the

prerogative being invoked is clearly a managerial

one.

A close scrutiny of the objectionable provisions of

the Code reveals that they are not purely business-

oriented nor do they concern the management

aspect of the business of the company as in the San

Miguel case. The provisions of the Code clearly

have repercussions on the employee's right to

security of tenure. The implementation of the

provisions may result in the deprivation of an

employee's means of livelihood which, as correctly

pointed out by the NLRC, is a property right. In view

of these aspects of the case which border on

infringement of constitutional rights, we must uphold

the constitutional requirements for the protection of

labor and the promotion of social justice, for these

factors, according to Justice Isagani Cruz, tilt "the

scales of justice when there is doubt, in favor of the

worker".

Verily, a line must be drawn between management

prerogatives regarding business operations per se

Class 5 - Digests Labor Relations 2

and those which affect the rights of the employees.

In treating the latter, management should see to it

that its employees are at least properly informed of

its decisions or modes action. PAL asserts that all its

employees have been furnished copies of the Code.

Public respondents found to the contrary, which

finding, to say the least is entitled to great respect.

(PAL posits the view that by signing the 1989-1991

collective bargaining agreement, on June 27, 1990,

PALEA in effect, recognized PAL's "exclusive right to

make and enforce company rules and regulations to

carry out the functions of

management without having to discuss the same

with PALEA and much less, obtain the

latter's conformity thereto" (pp. 11-12, Petitioner's

Memorandum; pp 180-181, Rollo.) Petitioner's view

is based on the following provision of the agreement:

The Association recognizes the right of the

Company to determine matters of management it

policy and Company operations and to direct its

manpower. Management of the Company includes

the right to organize, plan, direct and control

operations, to hire, assign employees to work,

transfer employees from one department, to another,

to promote, demote, discipline, suspend or

discharge employees for just cause; to lay-off

employees for valid and legal causes, to introduce

new or improved methods or facilities or to change

existing methods or facilities and the right to make

and enforce Company rules and regulations to carry

out the functions of management.)

The exercise by management of its prerogative shall

be done in a just reasonable, humane and/or lawful

manner.

Such provision in the collective bargaining

agreement may not be interpreted as cession of

employees' rights to participate in the deliberation of

matters which may affect their rights and the

formulation of policies relative thereto. And one such

mater is the formulation of a code of discipline.

Indeed, industrial peace cannot be achieved if the

employees are denied their just participation in the

discussion of matters affecting their rights. Thus,

even before Article 211 of the labor Code (P.D. 442)

was amended by Republic Act No. 6715, it was

already declared a policy of the State, "(d) To

promote the enlightenment of workers concerning

their rights and obligations . . . as employees." This

was, of course, amplified by Republic Act No 6715

when it decreed the "participation of workers in

decision and policy making processes affecting their

rights, duties and welfare." PAL's position that it

cannot be saddled with the "obligation" of sharing

management prerogatives as during the formulation

of the Code, Republic Act No. 6715 had not yet been

enacted (Petitioner's Memorandum, p. 44; Rollo, p.

212), cannot thus be sustained. While such

"obligation" was not yet founded in law when the

Code was formulated, the attainment of a

harmonious labor-management relationship and the

then already existing state policy of enlightening

workers concerning their rights as employees

demand no less than the observance of

transparency in managerial moves affecting

employees' rights.

Nonetheless, whatever disciplinary measures are

adopted cannot be properly implemented in the

absence of full cooperation of the employees. Such

cooperation cannot be attained if the employees are

restive on account, of their being left out in the

determination of cardinal and fundamental matters

affecting their employment.

DISPOSITION:

Petition is dismissed.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- LABOR - Consolidated Case Digests 2012-2017Dokument1.699 SeitenLABOR - Consolidated Case Digests 2012-2017dnel13100% (4)

- Marcelino Lontok, Jr. For Respondents. Complaint vs. Philippine Bank of Communications, Respondent." During TheDokument4 SeitenMarcelino Lontok, Jr. For Respondents. Complaint vs. Philippine Bank of Communications, Respondent." During TheChristian Robert YalungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests LaborDokument6 SeitenCase Digests LaborPriMa Ricel ArthurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Continental Marble vs. NLRC, Et. AlDokument1 SeiteContinental Marble vs. NLRC, Et. AlColmenares TroyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Relations Case Digest (Cases 4,6,7)Dokument6 SeitenLabor Relations Case Digest (Cases 4,6,7)May Ibarreta0% (3)

- Admelec Case DigestDokument8 SeitenAdmelec Case DigestWinnie Ann Daquil Lomosad-MisagalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case DigestDokument15 SeitenCase DigestEd Ech100% (1)

- Sanyo vs. Canizares Digest & FulltextDokument9 SeitenSanyo vs. Canizares Digest & FulltextBernie Cabang PringaseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest - Fuentes Vs NLRCDokument1 SeiteDigest - Fuentes Vs NLRCValentine MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonza V ABSCBN Case DigestDokument4 SeitenSonza V ABSCBN Case DigestYsabel Padilla89% (9)

- Century Properties Inc. vs. Babiano, Et Al., GR No. 220978, July 5, 2016Dokument1 SeiteCentury Properties Inc. vs. Babiano, Et Al., GR No. 220978, July 5, 2016Mark Catabijan CarriedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Domasig VsDokument2 SeitenDomasig Vsanne_ganzan80% (5)

- AFP Mutual Benefits Association v. NLRCDokument2 SeitenAFP Mutual Benefits Association v. NLRCPeanutButter 'n JellyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 43.0 Guevara Vs Guevara - Batch3Dokument1 Seite43.0 Guevara Vs Guevara - Batch3sarmientoelizabethNoch keine Bewertungen

- Enao Vs ECCDokument1 SeiteEnao Vs ECCCelinka ChunNoch keine Bewertungen

- FINAL CASE DIGEST - HernandezDokument71 SeitenFINAL CASE DIGEST - HernandezIa HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- ORO ENTERPRISES, INC., Petitioner, vs. NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION and LORETO L. CECILIO, Respondents.Dokument1 SeiteORO ENTERPRISES, INC., Petitioner, vs. NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION and LORETO L. CECILIO, Respondents.Charles Roger Raya100% (1)

- Paragele Vs Gma Network G.R. NO. 235315, JULY 13, 2020 FactsDokument2 SeitenParagele Vs Gma Network G.R. NO. 235315, JULY 13, 2020 FactsEd Ech100% (1)

- Legend Hotel Case DigestDokument2 SeitenLegend Hotel Case DigestKian Fajardo100% (1)

- Labor DigestDokument43 SeitenLabor DigestKling KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neri vs. NLRC, 1993 CASE DIGESTDokument2 SeitenNeri vs. NLRC, 1993 CASE DIGESTPatrick Chad Guzman33% (6)

- PHILIPPINE AIRLINES INC. v. SECRETARY OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT FRANKLIN M. DRILON and PHILIPPINE AIRLINES EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION PALEADokument1 SeitePHILIPPINE AIRLINES INC. v. SECRETARY OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT FRANKLIN M. DRILON and PHILIPPINE AIRLINES EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION PALEAEdvangelineManaloRodriguez100% (1)

- Labor 1 CasesDokument3 SeitenLabor 1 CasesLEIGHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Law Case DigestsDokument6 SeitenLabor Law Case DigestsGlenda TavasNoch keine Bewertungen

- San Miguel Vs NLRCDokument3 SeitenSan Miguel Vs NLRCHazel Angeline Q. AbenojaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Relations Case Digest - Set 4: Unfair Labor Practices ARTS. 259-260Dokument21 SeitenLabor Relations Case Digest - Set 4: Unfair Labor Practices ARTS. 259-260IanBiagtanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15, Ren Transport v. NLRCDokument1 Seite15, Ren Transport v. NLRCRebecca LongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hayden Kho Sr. Vs Dolores Nagbanua, Et. Al. G.R. No. 237246. July 29, 2019Dokument10 SeitenHayden Kho Sr. Vs Dolores Nagbanua, Et. Al. G.R. No. 237246. July 29, 2019Mysh PDNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 84484Dokument2 SeitenG.R. No. 84484hannahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Standards - Case Digest 1Dokument20 SeitenLabor Standards - Case Digest 1RS100% (3)

- Tongko vs. ManulifeDokument1 SeiteTongko vs. ManulifeMae NavarraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manila Mandarin vs. NLRCDokument1 SeiteManila Mandarin vs. NLRCJotham FunclaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agra Case DigestDokument18 SeitenAgra Case DigestCarla Virtucio50% (2)

- Neri V NLRCDokument3 SeitenNeri V NLRCMikaela Denise PazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests Labor StandardsDokument3 SeitenCase Digests Labor StandardsAxel GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest Legend Hotel Manila Vs RealuyoDokument4 SeitenDigest Legend Hotel Manila Vs RealuyoJay Kent Roiles0% (1)

- JiljilDokument2 SeitenJiljilCy PanganibanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21 - Alabang Country Club Inc Vs NLRCDokument3 Seiten21 - Alabang Country Club Inc Vs NLRCchiwi magdaluyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 22 Coca Cola Bottlers v. Dela CruzDokument3 Seiten22 Coca Cola Bottlers v. Dela Cruzaudreydql5100% (1)

- C.F. Sharp & Co. vs. Pioneer Insurance & Surety CorporationDokument2 SeitenC.F. Sharp & Co. vs. Pioneer Insurance & Surety CorporationDennis Jay Dencio ParasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notre Dame of Greater Manila Vs LaguesmaDokument1 SeiteNotre Dame of Greater Manila Vs LaguesmasfmarzanNoch keine Bewertungen

- San Miguel Corporation V MAERC Integrated ServicesDokument2 SeitenSan Miguel Corporation V MAERC Integrated ServicesbarcelonnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Case 124-147 DigestsDokument30 SeitenLabor Case 124-147 DigestsAnonymous QlsnjX1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Admin Cases (Digested) (1st)Dokument16 SeitenAdmin Cases (Digested) (1st)MCg Gozo100% (2)

- GR No. 200499 - San Fernando Coca-Cola VS Coca-Cola BottlersDokument3 SeitenGR No. 200499 - San Fernando Coca-Cola VS Coca-Cola BottlersMicah Clark-MalinaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assoc of Court of Appeals Employees Vs Hon Pura Ferrer CallejaDokument2 SeitenAssoc of Court of Appeals Employees Vs Hon Pura Ferrer CallejaVincent TalaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Relations Case DigestDokument16 SeitenLabor Relations Case Digestczeskajohann100% (1)

- Labor Relations Case DigestDokument39 SeitenLabor Relations Case DigestAndrade Dos LagosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Cases (ER-EE Relationship)Dokument22 SeitenLabor Cases (ER-EE Relationship)Val Justin DeatrasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aklan Electric Cooperative Incorporated v. NLRCDokument2 SeitenAklan Electric Cooperative Incorporated v. NLRCheinnah100% (2)

- Apex Mining Co. V NLRCDokument2 SeitenApex Mining Co. V NLRCPaulo Tapalla100% (3)

- Labor Law 2 CasesDokument23 SeitenLabor Law 2 CasesSara Andrea Santiago100% (1)

- Genaro Bautista v. CADokument2 SeitenGenaro Bautista v. CAMCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests - Labor Rev - Atty LorenzoDokument90 SeitenCase Digests - Labor Rev - Atty LorenzoRewsEn50% (2)

- PAL Vs NLRCDokument4 SeitenPAL Vs NLRCEm RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06 PAL V NLRC (Enriquez)Dokument2 Seiten06 PAL V NLRC (Enriquez)Frances Angelica Domini KoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PAL Vs NLRC 1993Dokument2 SeitenPAL Vs NLRC 1993Pilyang SweetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Which Affect The Rights of The Employees. in Treating The Latter, Management Should See To It That Its Employees Are at Least ProperlyDokument2 SeitenWhich Affect The Rights of The Employees. in Treating The Latter, Management Should See To It That Its Employees Are at Least ProperlyCindee YuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pal VS NLRCDokument2 SeitenPal VS NLRCraminicoffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pal Vs NLRCDokument3 SeitenPal Vs NLRCNielle BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coronel Vs Capati - DigestDokument2 SeitenCoronel Vs Capati - DigestRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oblicon Case DigestsDokument3 SeitenOblicon Case DigestsRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samson Vs Era - DigestDokument2 SeitenSamson Vs Era - DigestRowena Gallego33% (3)

- Towne and City Development Vs CA - DigestDokument3 SeitenTowne and City Development Vs CA - DigestRowena Gallego100% (1)

- Commercial Credit Vs CADokument2 SeitenCommercial Credit Vs CARowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cemco Holdings Vs National Life InsuranceDokument3 SeitenCemco Holdings Vs National Life InsuranceRowena Gallego100% (2)

- Wilson Vs Rear - DigestDokument2 SeitenWilson Vs Rear - DigestRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of ComplaintDokument2 SeitenAffidavit of ComplaintRowena Gallego100% (2)

- Villahermosa Vs Atty Caracol - DigestDokument2 SeitenVillahermosa Vs Atty Caracol - DigestRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Re AlmacenDokument4 SeitenIn Re AlmacenRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ong, Et Al vs. Roban Lending-PledgeDokument3 SeitenOng, Et Al vs. Roban Lending-PledgeRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 87.modesto Vs ModestoDokument2 SeitenRule 87.modesto Vs ModestoRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Table of LegitimesDokument6 SeitenTable of LegitimesRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transpo NotesDokument28 SeitenTranspo NotesRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portugal Vs Portugal-Beltran - DigestDokument3 SeitenPortugal Vs Portugal-Beltran - DigestRowena Gallego100% (1)

- Civpro Cases - Rule 12 & 16Dokument5 SeitenCivpro Cases - Rule 12 & 16Rowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Digested CasesDokument5 SeitenCivil Procedure Digested CasesRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of ComplaintDokument2 SeitenAffidavit of ComplaintRowena Gallego100% (2)

- Rule 2 - Civil ProcedureDokument3 SeitenRule 2 - Civil ProcedureRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 14 - Civil ProcedureDokument3 SeitenRule 14 - Civil ProcedureRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perfecto Dy Vs CADokument2 SeitenPerfecto Dy Vs CARowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 14 - Civil ProcedureDokument3 SeitenRule 14 - Civil ProcedureRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PD 979 - Marine Pollution DecreeDokument5 SeitenPD 979 - Marine Pollution DecreeRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sps Yap vs. Dy, Et Al - DigestDokument4 SeitenSps Yap vs. Dy, Et Al - DigestPaolo BrillantesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civpro Cases - Rule 12 & 16Dokument5 SeitenCivpro Cases - Rule 12 & 16Rowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 15 - Admin ReportDokument19 SeitenChapter 15 - Admin ReportRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On TreatiesDokument3 SeitenNotes On TreatiesRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marine Pollution DecreeDokument17 SeitenMarine Pollution DecreeRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oil Pollution Compensation Act of 2007Dokument28 SeitenOil Pollution Compensation Act of 2007Rowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests Pano - Pano.posadasDokument7 SeitenCase Digests Pano - Pano.posadasRowena GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Finra Ruling in Larry Hagman's Case Against CitigroupDokument7 SeitenFinra Ruling in Larry Hagman's Case Against CitigroupDealBookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Correctional Administration Q ADokument62 SeitenCorrectional Administration Q AAngel King Relatives100% (1)

- Quitoriano v. JebsenDokument2 SeitenQuitoriano v. JebsenMa Charisse E. Gaud - BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cleaving Clientelism Berlin May 2010Dokument27 SeitenCleaving Clientelism Berlin May 2010Manuel L. Quezon IIINoch keine Bewertungen

- Administrative Denial of Protest Appeal - Ingulli-Kemp (New Hanover County) - SERVEDDokument10 SeitenAdministrative Denial of Protest Appeal - Ingulli-Kemp (New Hanover County) - SERVEDBen SchachtmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. SolidumDokument2 SeitenPeople v. SolidumJames Amiel VergaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admission and ConfessionDokument9 SeitenAdmission and ConfessionAmmirul AimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- History GabrielaDokument10 SeitenHistory Gabrielaredbutterfly_766Noch keine Bewertungen

- Quasi-Delict (January 6, 20180Dokument156 SeitenQuasi-Delict (January 6, 20180Kim Boyles FuentesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ilr April 2013 PDFDokument202 SeitenIlr April 2013 PDFsnkulkarni_indNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNA-USA Rules of Procedure ChartDokument1 SeiteUNA-USA Rules of Procedure Chartchantillymun50% (2)

- JatinDokument1 SeiteJatinhappybhogpurNoch keine Bewertungen

- State Bank of India Vs Sarathi Textiles and Ors 21SC2002080818160429152COM54278Dokument2 SeitenState Bank of India Vs Sarathi Textiles and Ors 21SC2002080818160429152COM54278Advocate UtkarshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Email ID's List of Judicial Officers of High Court of Judicature at AllahabadDokument27 SeitenEmail ID's List of Judicial Officers of High Court of Judicature at AllahabadJudiciary100% (1)

- Digests EthicsDokument14 SeitenDigests EthicsAlvin Varsovia100% (1)

- Board Resolution Approving Sale of AssetsDokument0 SeitenBoard Resolution Approving Sale of AssetsshekhawatrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amiga Inc v. Hyperion VOF - Document No. 39Dokument25 SeitenAmiga Inc v. Hyperion VOF - Document No. 39Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Internal Reconstruction of CompaniesDokument5 SeitenIntroduction To Internal Reconstruction of CompaniesIrfan Aijaz100% (1)

- SenatorsDirectory PDFDokument200 SeitenSenatorsDirectory PDFSajhad HussainNoch keine Bewertungen

- LTD Finals For ReviewDokument1 SeiteLTD Finals For ReviewJao SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDokument2 SeitenBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledAbegail LeriosNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Harris, C.A.A.F. (2005)Dokument29 SeitenUnited States v. Harris, C.A.A.F. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- OutlineDokument6 SeitenOutlineCarla January OngNoch keine Bewertungen

- In The Court of The 5 Additional Chief Metroplitan Magistrate at BangaloreDokument5 SeitenIn The Court of The 5 Additional Chief Metroplitan Magistrate at BangaloreShekar Lakshmana SastryNoch keine Bewertungen

- (COPYR) 33 - Matthew Bender Vs West Publishing - PenafielDokument4 Seiten(COPYR) 33 - Matthew Bender Vs West Publishing - PenafielEon PenafielNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Gujarat Prohibition Act, 1949Dokument29 Seiten4 Gujarat Prohibition Act, 1949Stannis SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Articles of ImpeachmentDokument18 SeitenThe Articles of Impeachmentsilverbull867% (3)

- Case DigestDokument9 SeitenCase Digestevoj merc100% (1)

- Jess 401Dokument12 SeitenJess 401saurish AGRAWALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisprudence - TutorialDokument2 SeitenJurisprudence - TutorialNelfi Amiera MizanNoch keine Bewertungen