Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisdd

Hochgeladen von

sharu42910 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

18 Ansichten3 Seiten44922159 ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisdd

Originaltitel

44922159 ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisdd

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument melden44922159 ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisdd

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

18 Ansichten3 SeitenABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisdd

Hochgeladen von

sharu429144922159 ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisdd

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 3

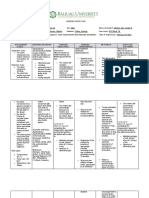

16 ABC of Emergency Differential Diagnosis

The possibility of typhoid or paratyphoid in particular is possible

given a relatively low efcacy of the vaccine (5570%) and the

history of ice consumption.

Examination

Observations are as follows: blood pressure 90/60 mmHg, pulse

60 beats/min, temperature 38.9C, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min,

oxygen saturations 98% on air. On general examination he appears

unwell and lethargic with a greyish pallor. He is not jaundiced; there

is no evidence of anaemia, lymphadenopathy, clubbing or cyanosis.

There are a couple of blanching, pink maculae on his ank, but

otherwise no evidence of rash on his skin.

There are ne crackles in both lung bases. His JVP is not visible.

Heart sounds are normal, with no ankle oedema. His abdomen is

soft but generally tender. The tip of the liver can just be felt, but

no other organomegaly or masses are palpable. Bowel sounds are

present. He is neurologically fully intact with a Glasgow Coma Score

of 15/15. Fundoscopy is normal and he has no neck stiffness.

Question: Given the history and

examination ndings what is your

principal working diagnosis?

Principal working diagnosis enteric fever

Malaria is still possible. Hypotension and his lethargic, unwell

appearance point to this, but the absence of jaundice, pronounced

pallor or hepatosplenomegaly casts doubt. Meningitis is unlikely

as the headache is not accompanied by meningism. Septicaemia

of some type is still possible. Amoebic liver abscess might be a

possibility, although one would expect more pronounced right

upper quadrant pain and tenderness. The lack of respiratory

symptoms or signs makes pneumonia unlikely. Enteric fever is

much more likely given the presence of pink macules (possible rose

spots), accompanied by diffuse abdominal tenderness, mild anaemia

and mild hepatitis, and a heart rate of 60 in a febrile patient.

Management

This patient requires urgent uid resuscitation and oxygen.

Investigation includes full blood count, renal and liver function

tests, ESR, CRP and chest X-ray. Three thick blood lms specically

for malaria parasites and haemolysis should be sent urgently. Blood,

urine, and stool should be cultured. If these do not yield a result,

bone marrow aspirate culture should be considered. Do not request

a Widal test for typhoid; it has been abandoned by most laborato-

ries in the UK due to difculty in the interpretation of results. Your

laboratory may have the newer rapid antigen tests available. Urinary

antigen testing should be performed if Legionella is suspected.

If meningitis is suspected in the absence of a classic meningococ-

cal rash, a lumbar puncture should be performed to conrm the

diagnosis and identify the organism unless contraindicated. If the

history and examination point to pneumococcal meningitis a dose

of steroids with the rst dose of antibiotics can improve outcome.

As enteric fever is likely, treatment with i.v. ceftriaxone or

cefotaxime should be initiated whilst awaiting the microbiological

Figure 4.5 Pulmonary tuberculosis. Image kindly provided by Dr Andrew

McDonald Johnston, www.doctors.net.uk

Figure 4.6 Rose spots in the context of typhoid. Image courtesy of the

Health Protection Agency via Doctors mess, www.doctors.net.uk

Box 4.1 Non-infective causes of fever

Malignancy

Autoimmune diseases

Drug reactions allergic reactions to, or metabolic consequences

of the drug

Seizures

Environmental fever (due to very high external temperatures, or

excessive exercise)

Hyperthyroidism

Thrombosis

Infarction of myocardium, kidney, or lung (auto-immune

element)

Blood transfusion reaction

Atmospheric pollution (e.g. nitrogen dioxide)

Factitious fever (Munchausens syndrome/Munchausens by proxy)

High Fever 17

results and sensitivity testing. The patient may require inotropic

support. Management in an infectious diseases unit is appropriate.

Outcome

This patients investigations showed negative malaria lms, mild

anaemia, lymphopaenia, mild abnormalities of liver function and a

normal chest X-ray. His ESR was 87 and CRP 264. Salmonella Typhi

subsequently grew on stool culture. He was managed in an infec-

tious diseases unit with uids and intravenous ceftriaxone, and was

monitored for development of ileal perforation by measuring girth

size. He made a full recovery.

Further reading

Connor BA, Schwartz E. Typhoid and paratyphoid fever in travellers. Lancet

Infectious Diseases 2005; 5:623628.

Cook GC (Ed.). Mansons Tropical Diseases, 21st Edition. Saunders, London,

2003.

Felton JM, Bryceson AD. Fever in the returning traveller. British Journal of

Hospital Medicine 1996; 55:705711.

Health Protection Agency website: www.hpa.org.uk

Heyderman RS on behalf of the British Infection Society. Early management

of suspected bacterial meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia in

immunocompetent adults. Journal of Infection 2005; 50:373374. Also

www.meningitis.org

Lalloo DG, Shingadia D, Pasvol G et al. UK malaria treatment guidelines.

Journal of Infection 2007; 54:111121.

Ledingham JG, Warrell DA. Concise Oxford Textbook of Medicine. Oxford

University Press, Oxford, 2000.

Spira AM. Assessment of travellers who return home ill. Lancet 2003;

361:14591469. www.britishinfectionsociety.org

www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthprotection/Immunisation/Greenbook/

DH_4097254. Immunisation against Infectious Disease the Green Book.

www.wrongdiagnosis.com/f/fever/causes.htm

18

CHAPTER 5

Vaginal Bleeding

Sian Ireland and Karen Selby

ABC of Emergency Differential Diagnosis. Edited by F. Morris and A. Fletcher.

2009 Blackwell Publishing, ISBN: 978-1-4051-7063-5.

Question: What differential diagnosis

would you consider from the history?

The differential diagnosis of heavy vaginal bleeding is listed in

Box 5.1.

This woman could be pregnant as she has not had a period for

8 weeks. Bleeding in early pregnancy is most often due to a mis-

carriage, but ectopic pregnancy is the other important diagnosis

to consider.

Miscarriage

Spontaneous miscarriage is the loss of a pregnancy before 24 weeks

gestation. It is thought that around 1020% of pregnancies result

in spontaneous miscarriage. The majority are due to embryonic

abnormalities with a small percentage attributable to maternal

health factors such as diabetes, renal disease, autoimmune dis-

orders, trauma and infections, or structural abnormalities of the

reproductive tract (see Figure 5.1).

Threatened miscarriage. This is vaginal bleeding during 1

early pregnancy without the passage of tissue. The cervi-

cal os remains closed and a viable pregnancy is seen in the

uterus. About half will progress to an actual miscarriage.

The bleeding and accompanying pain is not usually severe,

and on vaginal examination the os is closed and there is no

cervical excitation.

Inevitable miscarriage. There is dilatation of the cervical canal 2

and bleeding is usually more severe.

Incomplete miscarriage. Vaginal bleeding is more intense and 3

accompanied by abdominal pain. On vaginal examination the os

is open and tissue is being passed. The presence of tissue in the os

itself can cause cervical shock low blood pressure accompanied

by bradycardia due to vagal stimulation. If the tissue is removed

with sponge forceps the shock will usually resolve.

Complete miscarriage. This is said to have occurred when the 4

fetus and the entire placenta have been passed. There is a his-

tory of vaginal bleeding and pain which has usually subsided.

Ultrasound scan reveals an empty uterus.

Delayed or missed miscarriage. This can only be diagnosed by 5

ultrasound scan when a gestational sac with a mean diameter

of more than 20 mm is seen but there is no fetal pole, or a fetal

pole greater than 6 mm is present but no fetal heart pulsation is

detected. These may present with slight vaginal bleeding.

Ectopic pregnancy

This occurs when a fertilised ovum implants at a site other than in

the uterus. Most often it occurs in the fallopian tubes but also occur

within the abdomen, cervix or ovary (see Box 5.2 and Figure 5.2).

CASE HISTORY

A 36-year-old, obese, diabetic woman presents with a 5-day

history of heavy vaginal bleeding. She is passing clots and using

more than 10 pads per day. The bleeding is accompanied by

right-sided lower abdominal pain that is constant and becoming

more severe. She has not vomited but has lost her appetite. In her

early twenties she was treated for a sexually transmitted infection.

She has a long history of irregular periods attributed to polycystic

ovary syndrome (PCOS), and has previously tried clomiphene in

order to try to become pregnant. Her last menstrual period was 8

weeks ago but given her menstrual irregularity she is not overly

concerned by this. She is sexually active and is not using any

contraception. She has no other medical problems and there is no

family history of a tendency to bleed.

Box 5.1 Causes of vaginal bleeding

Non-pregnant

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding

Cervical erosion

Cervical polyps

Infection

Malignancy

Early pregnancy

Spontaneous miscarriage

Ectopic pregnancy

Late pregnancy

Placental abruption

Placenta praevia

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- TFCO Healthy Food in SchoolsDokument12 SeitenTFCO Healthy Food in Schoolssharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Conduct Rule GazetteDokument1 SeiteConduct Rule Gazettesharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Comparison CarsDokument5 SeitenComparison Carssharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tamil Nadu State Services Rules SummaryDokument100 SeitenTamil Nadu State Services Rules SummaryJoswa Santhakumar100% (1)

- Compliance HandBook FY 2015-16Dokument32 SeitenCompliance HandBook FY 2015-16sunru24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Healthy Eating PlannerDokument10 SeitenHealthy Eating Plannerjasdfl asdlfjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hospitals and Healthy FoodDokument8 SeitenHospitals and Healthy Foodsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- UW Path NoteDokument218 SeitenUW Path NoteSophia Yin100% (4)

- Healthy EatingDokument2 SeitenHealthy Eatingsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia: To Treat or Not To Treat: ReviewDokument8 SeitenAsymptomatic Hyperuricemia: To Treat or Not To Treat: ReviewkkichaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Renal Urology HistoryDokument131 SeitenRenal Urology Historysharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- T - Nadu Govt Servants Conduct RulesDokument42 SeitenT - Nadu Govt Servants Conduct Rulessharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Usmle Hy Step1Dokument20 SeitenUsmle Hy Step1Sindu SaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Estado Hiperosmolar HiperglucemicoDokument8 SeitenEstado Hiperosmolar HiperglucemicoMel BlancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neeraj S Notes Step3Dokument0 SeitenNeeraj S Notes Step3Mrudula Rao100% (1)

- Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Nonketotic Syndrome: R. Venkatraman and Sunit C. SinghiDokument6 SeitenHyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Nonketotic Syndrome: R. Venkatraman and Sunit C. Singhisharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisweeqe PDFDokument3 SeitenABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisweeqe PDFsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- ChoiDokument19 SeitenChoiLuciana RafaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approach To A Case of Hyperuricemia: Singh V, Gomez VV, Swamy SGDokument7 SeitenApproach To A Case of Hyperuricemia: Singh V, Gomez VV, Swamy SGsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Molecules 18 08976Dokument18 SeitenMolecules 18 08976sharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 23: Hyperuricemia and Gout: BackgroundDokument2 SeitenChapter 23: Hyperuricemia and Gout: Backgroundsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 23: Hyperuricemia and Gout: BackgroundDokument2 SeitenChapter 23: Hyperuricemia and Gout: Backgroundsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Disorders of Nucleotide Metabolism: Hyperuricemia and Gout: Uric AcidDokument9 SeitenDisorders of Nucleotide Metabolism: Hyperuricemia and Gout: Uric AcidSaaqo QasimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prospectus MDMSJULY2015Dokument39 SeitenProspectus MDMSJULY2015sharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Alcohol WithdrawalDokument3 SeitenAcute Alcohol Withdrawalsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Approach To A Case of Hyperuricemia: Singh V, Gomez VV, Swamy SGDokument7 SeitenApproach To A Case of Hyperuricemia: Singh V, Gomez VV, Swamy SGsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisbbxc PDFDokument3 SeitenABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisbbxc PDFsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosissssv PDFDokument3 SeitenABC Emergency Differential Diagnosissssv PDFsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisssbbfvvcv PDFDokument3 SeitenABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisssbbfvvcv PDFsharu4291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Stress Management in StudentsDokument25 SeitenStress Management in StudentsJangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monoclonal Antibodies The Next Generation April 2010Dokument10 SeitenMonoclonal Antibodies The Next Generation April 2010Al ChevskyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychology of Al-GhazaliDokument48 SeitenPsychology of Al-GhazaliZainudin IsmailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Country Presentation: CambodiaDokument11 SeitenCountry Presentation: CambodiaADBI Events100% (1)

- Nursing ProcessDokument118 SeitenNursing Processɹǝʍdןnos100% (30)

- Q-MED ADRENALINE INJECTION 1 MG - 1 ML PDFDokument2 SeitenQ-MED ADRENALINE INJECTION 1 MG - 1 ML PDFchannalingeshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spina Bifida OCCULTADokument1 SeiteSpina Bifida OCCULTArebelswanteddot_comNoch keine Bewertungen

- JBL FO Product Range 2015Dokument16 SeitenJBL FO Product Range 2015Victor CastrejonNoch keine Bewertungen

- End of Life ManualDokument238 SeitenEnd of Life ManualJeffery TaylorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sotai ExercisesDokument2 SeitenSotai Exerciseskokobamba100% (4)

- DAILY LESSON Plan 4 - 1.8Dokument4 SeitenDAILY LESSON Plan 4 - 1.8Wilbeth PanganibanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Puyer Asthma and Diare Medication DosagesDokument1 SeitePuyer Asthma and Diare Medication DosagesAlbert SudharsonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- TramadolDokument19 SeitenTramadolanandhra2010Noch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write A Systematic ReviewDokument8 SeitenHow To Write A Systematic ReviewNader Alaizari100% (1)

- Sociology Final ProjectDokument16 SeitenSociology Final Projectabt09Noch keine Bewertungen

- Copy Pedia DrugsDokument3 SeitenCopy Pedia DrugsMonica LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analgezia Si Anestezia in Obstetrica. Analgezia IN Travaliu: IndicatiiDokument31 SeitenAnalgezia Si Anestezia in Obstetrica. Analgezia IN Travaliu: IndicatiiAlex GrigoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Registered Dietitians in Primary CareDokument36 SeitenRegistered Dietitians in Primary CareAlegria03Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yakult ProfileDokument36 SeitenYakult ProfileMubeen NavazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dysfunctional Gastrointestinal Motility Maybe Related To Sedentary Lifestyle and Limited Water Intake As Evidenced byDokument6 SeitenDysfunctional Gastrointestinal Motility Maybe Related To Sedentary Lifestyle and Limited Water Intake As Evidenced byCecil MonteroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breast Cancer FactsDokument2 SeitenBreast Cancer FactsScott CoursonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ferenczi - My Friendship With Miksa SchachterDokument4 SeitenFerenczi - My Friendship With Miksa SchachtereuaggNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critiquing 1Dokument3 SeitenCritiquing 1Nilesh VeerNoch keine Bewertungen

- IssuancesDokument347 SeitenIssuancesReia RuecoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biosimilar Insulin GlargineDokument59 SeitenBiosimilar Insulin GlarginenellizulfiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applications of Humic and Fulvic Acids in AquacultureDokument2 SeitenApplications of Humic and Fulvic Acids in AquacultureAlexandra Nathaly Beltran Contreras100% (1)

- NCP Pancreatic MassDokument4 SeitenNCP Pancreatic MassJan Lianne BernalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Introduction To AcupointsDokument48 SeitenGeneral Introduction To Acupointsjonan hemingted10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Quality Assurance in IV TherapyDokument37 SeitenQuality Assurance in IV TherapyMalena Joy Ferraz VillanuevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Código Descripción Costo Unita. Existencia Unidades Costo Existencia Precio 1 %utilDokument24 SeitenCódigo Descripción Costo Unita. Existencia Unidades Costo Existencia Precio 1 %utilNiky Dos SantosNoch keine Bewertungen