Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

CEEOL Article

Hochgeladen von

Bolota Roxana MariaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CEEOL Article

Hochgeladen von

Bolota Roxana MariaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Psychosocialaspectsofaggressioninschoolenvironment

Psychosocialaspectsofaggressioninschoolenvironment

byMonikaCsibiSndorCsibi

Source:

RomanianJournalofSchoolPsychology(formerlyRevistadePsihologieScolara)(RomanianJournal

ofSchoolPsychology),issue:8/2011,pages:3247,onwww.ceeol.com.

Romanian Journal of School Psychology, 2011

Vol. 4, No. 8, pp. 32-47

PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF AGGRESSION

IN SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT

1

Sndor Csibi

*

Babe-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca

Romania

Monika Csibi

**

Reformed High School, Trgu Mure

Romania

Abstract

We analyzed the phenomenon of adolescent aggression showing a strongly

increasing tendency, as evidenced both by professionals in the educational

system, parents, and mass - media. Our goal was to identify possible

sources of aggression, such as the level of perceived psychological stress,

self-appreciation, and conflict solving strategies by our teenager

participants. The main approaches of aggression in our analysis refers to

individual (gender, self-image, coping modalities) and social (cultural,

class type) differences of the surveyed teenagers. We used the following

instruments: Anger Expression Scale; Ways of Coping; Perceived Stress

Scale; Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. The participants were 109, 10

th

grade

students, with a mean age of 16 years old. The results show significant

correlations between the level of self-esteem, perceived stress, coping

modalities and the level of expressed aggression. Internal or external

orientations of aggression show differences depending on the subjects

gender. Perceived mental stress presents higher values among girls and is

closely related to expression and orientation of aggressive behavior. Global

self-esteem level is higher among boys and shows correlation with the

expression of aggression and the adopted coping modalities. The discussed

issues may have impact on planning more efficient aggression prevention

programs in schools.

Keywords: expressed aggression; external/internal directed aggression;

conflict resolution modalities; stress; self-esteem

Introduction

Our study shares the increased attention of national and international

scientific communities toward the psycho-social aspects of aggression,

represented by numerous studies and by recent researches.

1

Investing in people! PhD scholarship, Project co-financed by the European Social Fund,

Sectorial Operational Program Humanistic Resources Development 2007 2013, Babe-

Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

*

school psychologist, PhD student in sociology, Babe-Bolyai University, Faculty of

Sociology and Social Work, Cluj-Napoca, Romania; e-mail: sandor.csibi@ubbcluj.ro

**

school psychology, PhD, Reformed High School Trgu-Mure, Romania; e-mail:

csibimonika@yahoo.com

Access via CEEOL NL Germany

Psychosocial aspects of aggression in school environment 33

The problem of aggression is a frequently emphasized issue in

contemporary approaches of social problems and politics, and underlined

often by professionals from the educational system, researchers, parents and

also media sources. The actuality and novelty of our study is conferred by the

multiple changes in the teenagers lifestyle, anchored in societies and cultural-

economical changes characteristic for the present day.

The study focuses on the phenomenon of aggression, framed in a

specific psycho-social context, and also contributes to shaping a

comprehensive image about the Romanian teenagers particularities. In our

conception the aggressive behavior should be primary treated from social-

psychological perspective, specifically focusing on the individuals

perceptions of threat, others and the self. A persons self-appreciation is

formed through social experiences, needed to be considered if we want to

understand the processes that have violent behavior as outcomes. Changing

one's social perceptions in a positive way might be the proper approach for

efficiently reducing violence.

In our study we consider the psychosocial risk factors for aggressive

behavior through individual and social / contextual perspectives. Individual

factors involve a complex interplay of physiological, cognitive, affective, and

behavioral variables and are rooted in past behavior or experiences. Social-

contextual factors have to do with family and peer relationships, as well as

environmental conditions and experiences. Individual and social-contextual

factors might change to different degrees. Somebodys risk for violence will

be the product of dynamic interplay between these factors that increase or

decrease the likelihood of offending (Borum & Verhaagen, 2006). Personal

experiences with violence that share a common cultural familiarity could be

viewed as a determining factor of social environment that facilitate or regulate

violent behaviors in schools (Benbenishty & Astor, 2005).

Increased psychic and social pressure can lead, through difficulties in

adjustment and coping with them, to deficiencies in pro-social behavior and

more frequent violent reaction (Benbenishty & Astor, 2005).

As a scientific question we consider interesting especially the analysis

of relationships between the expression of aggression and the coping

modalities adopted in stressful or problematic situations. Both variables are

socially and culturally determined. Also they are significantly influenced by

personality differences. However teenage aggression can be the consequence

of increased psychic pressure and one of the preventive methods related to

aggressive behavior could be the increase of self-appreciation and the

efficiency of coping modalities.

Psychosocial investigations of expressive aggression behavior

emphasize the socio-cultural conditioning of the teenagers reactions toward

everyday challenges and risk behavior (smoking, substance use, social

isolation, gang affiliation, unhealthy eating habits) as a social phenomenon

(Lupu & Zanc, 1999).

Sndor Csibi, Monika Csibi 34

The analysis of behavioral tendencies among teenagers in a larger

actual social context allows a better understanding of the relationship between

values-attitudes-opinions-behavior, and the characteristics of mentalities

among teenagers (Rotariu & Ilu, 2006). The consciousness of social context

details surrounding school violence also leads to a better understanding of the

potential power of the peer circle, the staffs response, or gender differences

on the school ground. The result of our scientific approach is a better

explanation and intervention in the processes of school violence.

Manifestation of aggression in adolescence

Aggression is described in the literature as a typical reaction to anger,

although it can also occur due to other causes. Anger can stem from anxiety

or different psychic tensions, or can be caused by different conflicts without

solutions, envy, threats, misunderstandings between different social entities.

Several psychological theories describe aggression as a personality

trait with innate and learned factors. The study of aggression needs to

consider the intake of it on personality construction. In a normal measure,

aggression is necessary for surviving, in the case of a psychologically and

physically healthy man. The barriers that appear in the way of aggression

expression lead to the involvement of different mechanisms used to fight

against the new situation. However from a socio-psychological perspective in

most cases the aggressive behavior is perceived as a deviant behavior,

situated in conflict with individual or community values (family, school,

peers) and with the interests of social factors involved in educational

processes (Ilu, 1994).

According to researches, the aggressive behavior manifested in

interpersonal relationships of teenagers proves to be stabile in time. The early

childhood aggression constitutes a confident predictor of later negative

personality traits. The aggressive behavior is determined by the internalized

models of actions, crystallized through previous social experiences. These

models can be learned and might be characterized by animosity, mistrust or

deception (Lansford et al., 2006). The individual reaction tendency of

adolescents toward various stimuli and the motivational structures determines

the establishment of continuance in aggressive behavior.

These constructs of personality contain cognitive components also,

which in case of high level of aggression might cause biased perception of a

certain life situation. In a certain social scene a person can perceive others

reactions as hostile, provocative or aggressive. The deficiencies in social

information processing have their roots in early social experiences (Olweus,

1984).

The analysis of aggression expression level and its orientation

modalities in exterior or toward the person inside offers us important data in

the circumscription of the problem of aggression and generally the level of

quality of life among teenagers. The expressions of anger and aggression

Psychosocial aspects of aggression in school environment 35

among other risk factors may be the predictors for different reactions to

stressful situations, and their consequences for mental health. When facing

frustrating situations teenagers may seek for other peoples help, may adopt

aggressive behavior, consume alcohol, smoke, use drugs, or invest more

effort in solving the situation (Langens & Morth, 2003). The adopted

modalities of answers will depend on the degree in which certain models

succeeded to solve a situation in the past and reduced successfully the

frustration or psychological tension.

Differences in the coping process and the aggressive behavior

The adopted coping strategies among aggressive persons are

predominantly characterized by avoidance mechanisms, possibly explained

because of distrusts in other persons. Physiological reactions underlying

aggression are often related to deficiency in health oriented behavior, such as

alcohol consuming, smoking, excessive use of coffee, and also the avoidance

of any support from other persons (Ogden, 2007). According to Pik (2007),

increasing environment expectancy, higher performance exigencies, family

conflicts, or school bullying, can lead to psychosomatic disorders and

symptoms, which in turn may strengthen an increased level of psychological

stress, and manifestation of aggression. Studies suggest that certain factors of

health oriented behavior (self-image, passive, sedentary lifestyle, alcohol use,

psychosomatic disorders) are associated with high levels of stress, low self-

esteem and a higher level of expressed aggression. (Lohaus et al., 2009).

Attribution researchers (Hazebroek et al., 2001) suggested that

children attributions characterized by a high level of aggression do not differ

significantly from those of other children. Researchers showed that in an

ambiguous situation aggressive children tend to internally attribute more

aggressive, offensive or provocative behaviors and manifestations, than their

less aggressive colleagues. The authors concluded that the experimental

results may be explained by the dysfunctional cognitions and failure to learn

emotionally adequate answers of children with higher level of aggression

manifestation (Lansford et al., 2006).

Even though many scientists were involved in school violence

research, several questions still remained unanswered. These concerned

within-school dynamics and the relationships to other social settings (e.g.

family or community). We consider that one of the most important issues is

the empirical evidences of how social factors in schools determine violence.

In the conflict solving process or in decreasing the tension and stress

of a problematic situation, the specific changes and challenges faced by

teenagers make necessary the use of efficient coping strategies for successful

adjustment (Olh, 1995; Pik, 1997). The coping processes assume specific

behaviors, the flexibility to adjust to various and complex environmental

challenges, and the functioning of efficient cognitive mechanisms through

adjustment (Spielberger, 2004, Litman, 2006).

Sndor Csibi, Monika Csibi 36

Studies sustain that the predominant adoption of passive coping styles

among teenagers and the repression of feelings, emotions show strong

correlations (Langens &Morth, 2003).

The expression of anger and hostile behavior is strongly related to

avoidance of environmental support seeking. Adjustment strategies in

predominantly aggressive teenagers contain biased cognitions. This might be

explained by their thinking about people, who generally cannot be trustful

(Ogden, 2007). The ability of emotional expressiveness affects indirectly the

behavior, through the influence of affiliation processes to mates of an age and

adults. Study results suggest that attachment and security facilitates socially

adequate behavior through assuring a high level of emotional consciousness,

empathy, and positive expressions (Lable, 2007).

Researches centered on personality analysis among adolescents found

that help seeking is strongly related to the positive characteristics of

personality, but is also present in the case of anger. Gender analysis revealed

that girls showed higher abilities in emotional expression than boys (Luebbers

et al., 2007). In anger expression researchers didnt find significant

differences between genders, but among boys the presence of outside oriented

aggression (toward the object which caused the frustration) was more

obvious, while among girls the anger was oriented predominantly toward

their own person (Zoccali et al., 2007). Better internal control of anger is

strongly related to the general tendency to inhibition of verbal aggression,

while in case of hostility we can observe the lack of control in verbal

aggression.

The coping modalities used in challenging situations develop and

become more various with age and experience. Researches show that in less

controllable situations teenagers are adopting predominant emotion centered

coping strategies (Smits & DeBoeck, 2007).

Under stress the adolescents often react aggressively. Researchers

showed that social stress factors (for example difficult economic situations,

including high unemployment levels, or politically tensed situations)

influenced the level of inter- and intra-personal (suicide) violence.

Perceived social support mediates between stress generated by the

social context and individual aggressive behavior. When an individual feels

supported and social solidary, outside stress is not translated into aggressive

behavior (Landau, 1998, cf. Benbenishty & Astor, 2005).

The ability in facing stressful situations also appears as a sign of

mental health (Buda, 2004). Difficulties in coping processes may act together

with depressive symptoms, stress, and anxiety. We emphasize that the

adjustment strategies are related to the specific of situations, to long term

consequences, and also to the controllability level of stress (Wrezniewsky &

Chlinska, 2007).

In aggression analysis it is important to consider the personality as a

whole. The answer given in a stressful or threatening situation and the

Psychosocial aspects of aggression in school environment 37

selected coping modalities will be influenced both by the abilities and

previous experiences of a person and by the environmental and educational

factors (Hardi, 1992).

Self-image and self-appreciation among teenagers

Adolescents tend to appreciate themselves through cultural ideals of

masculinity and femininity. Research in the field underlines the differences

between girls and boys. Interesting issues in adolescent studies examines

identification with others' feelings, empathy, as a dimension of relational

boundaries. High levels of emotional identification indicate a self-image that

is highly connected to other people (Aneshensel & Phelan, 1999).

The influences of previously experienced success and failure support

the teenagers in creating a self-image. This construct of personality will

include information about what they think about their abilities and

performance, and the way in which these fit the self or others expectances.

Depending on this evaluation or self-appreciation teenagers anticipate the

success in a situation or activity, which will support the personal involvement

in activities such as learning.

The disposition of self-evaluation is learned through the process of

socialization, when the person becomes aware of her own value compared to

others. The characteristics of cognitions and feelings about our own person

are the results of previous experiences where success or failure had a certain

determinant goal (Kaplan et al., 1994). Among teenagers self-appreciation is

influenced by factors such as physical development and changes, or

subjective satisfaction with body image. Results obtained by Currie &

Williams (2000) emphasized that girls who were less satisfied with their own

body and physical image reported lower self-esteem.

Teenagers with the tendency of negative self-appreciation, due to

failure anticipation, tend to experience negative affect (depression, anxiety,

anger). Researchers suggest that self-appreciation shows positive correlations

with anxiety and aggression; aggressive students were showing lower self-

esteem (Alsaker & Olweus, 1986). Other authors sustain that aggressive

manifestations in school environment has higher levels for boys (Furlong et

al., 2002). Increased self-esteem is associated with expectancies for success,

optimism toward future performances, fight for goal achieving and

persistence in obstacle oversteps.

The influences of the external contexts are mediated and directly

influenced by within-school contexts. In turn school policies regarding

violence may also mediate the influences of violent models or previous

experience. Researchers underlie that a viable theory of school violence needs

to explore detailed questions about the policies, practices, procedures, and

social influences within the school setting as well as the impact of the

individual variables (Benbenishty & Astor, 2005).

Sndor Csibi, Monika Csibi 38

Self-esteem is considered an essential characteristic of mental health,

being an individual variable relevant in the development of psychological

stress and disease (Cole & Cole, 1997). Self-esteem is influencing the

evaluation of stimuli and the use of coping resources and moderates the

effects of confrontations with stressful circumstances.

Methodology

Objectives and hypothesis

Our main objective is to achieve a better understanding of the psycho-

social factors influencing the behavioral tendencies in our group of

participants. We also want to obtain a better understanding of the school

violence phenomenon from the multidisciplinary perspectives of psycho-

social aspects.

The specific objectives of our research are:

The investigation of personality particularities and the description of the

implications of the school environment in which the aggressive

manifestations take place;

The identification of relevant factors influencing school violence,

prevention programs efficiency and developing possibilities.

Our hypotheses were:

1. The level of expression and the orientation of aggression as personality

factors show significant differences depending on the participants

gender, age and school class type attending (exact sciences or humanistic

profile);

2. The manifestation of aggression shows a significant correlation with the

coping modalities and is strongly influenced by socially determined

contextual and intra-personal factors (perception of stress, self-

appreciation, coping abilities).

Participants

The research included 109 students from Tg. Mure high schools,

including 5 classes of 10

th

grade, randomly selected. The included high

schools were selected from neighborhood environments with a medium level

of performance. Students age ranged from 15 to17, with an average age of 16

years. Among the selected classes two had an exact sciences profile and three

classes had a humanistic profile. Among the exact sciences classes the gender

distribution was 20 boys and 42 girls total. In the humanistic classes 13 boys

and 34 girls were debriefed. The survey was conducted in November 2009

(2009-2010 academic years). Filling in the questionnaire battery took 40

minutes and it was administrated during a school class.

Psychosocial aspects of aggression in school environment 39

Measures

We took measures of:

1. Demographical data, such as: age, gender, school year and type;

2. Data concerning individual psychological factors included in our study

measured through different structured tests:

Anger Expression Scale (AES, Spielberger et al., 1985) evaluates the level

of aggression;

Ways of Coping (WOC, Lazarus & Folkman, 1985) describes the adopted

coping strategies (problem centered, emotion centered and support

seeking) when facing a stressful or problematic situation. The three ways

of coping contain 7 subgroups : planned problem solving, confront coping;

positive reappraisal; self-control; distancing and escape-avoidance; seeking

social support;

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES, Rosenberg, 1965) for measuring the

global perception of personal value and self-acceptance;

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10, Cohen & Williamson, 1988) to estimate

the level of chronic stress as a risk factor.

For statistical processing of the obtained data we used SPSS 11 for

Windows. The statistical analysis included descriptive statistics (mean,

standard dispersion), t-test for independent samples and variance analysis

(one-way ANOVA).

Results and discussion

We wanted to show whether the differences in the expression of

aggression might be determined by socio-cultural factor such as gender or

class type (attended by the students). We did not find significant differences

between boys and girls related to the level and orientation of aggression (see

Table 1). Previous studies also reported no gender differences in relational

aggression (see Archer & Coyne, 2005).According to our result the structure

of emotional and personality variables was rather associated with aggression

differentiated for boys and girls. Table 1 contains the obtained results,

although neither of factors significantly differs related to gender.

Table 1. Aggression expressions mean values, t-values and their significances

among boys and girls

Aggression Gender N Mean Std. Dev. t p

General level of aggression boys 33 49.24 8.25

- 0.64 0.52

(A/EX) girls 76 50.34 8.23

Level of repressed aggression boys 33 18.58 4.37

-0.39 0.69

(A/I) girls 76 18.92 4.21

Level of expressed aggression boys 33 18.97 5.00

0.10 0.91

(A/O) girls 76 18.86 5.56

Sndor Csibi, Monika Csibi 40

Burton et al. (2007) sustain that among boys aggression was

correlated with peer rejection and egocentricity, while in girls aggression was

related with low levels of life satisfaction, affective instability, affective

features of depression, and also egocentricity, self-harm behavior, and

bulimic symptoms.

Regarding the class type and the level of aggression we found

significant differences among students attending exact sciences and

humanistic classes in the outside expressed aggression form (see Table 2).

The mean value for expressed aggression (A/O) was 19.76 in the case of

exact sciences classes and significantly lower (17.74) in the case of

humanistic classes.

Table 2. The aggression expression differences related to class types

(mean, t-values, significance)

Aggression Class type N Mean Std. dev. t p

General level of aggression exact sciences 62 50.42 9.14

0.60 0.55

(A/EX) humanistic 47 49.47 6.86

Level of repressed aggression exact sciences 62 19.39 4.65

1.62 0.11

(A/I) humanistic 47 18.06 3.54

Level of expressed aggression exact sciences 62 19.76 5.40

1.96 0.05

(A/O) humanistic 47 17.74 5.16

In our analysis significant correlations (p < 0.01) were found between

the level of self-appreciation and perceived stress for boys and girls.

There was a difference between them depending on adopted coping

modalities (confront coping p < 0.01, escape-avoidance p < 0.05).

Researchers suggested that girls and boys tend to cope differently, and

that the girls coping styles place them more at risk for experiencing

depression. There is evidence in the coping literature that boys are more likely

to use problem-focused coping and that girls tend to use emotion-focused

coping. Thinking or worrying about a problem, the predominant presence of

emotional reactions, being overwhelmed by emotional substrates of a problem

is frequent in girls, while for boys results emphasize the presence of

emotionally distractive coping, for example exercising (Li, DiGiuseppe &

Froh, 2006).

According to the data in Table 3 the mean values of perceived stress

and self-esteem present significant differences between boys and girls. We

can say that the level of self-esteem is significantly higher for boys then for

girls (m

boys

= 29.48, m

girls

= 26.01, p < 0.01). Contrary, the level of perceived

stress shows significantly higher values for girls than for boys (m

girls

= 22.50,

m

boys

= 16.00, p < 0.01). Results also indicate that seeking social support is

more likely to be adopted by girls. These findings might be explained by

culturally learned patterns by girls toward keeping close relationships. Also

the level of self-esteem is related to the capacity to maintain satisfying

Psychosocial aspects of aggression in school environment 41

relationships in adolescence (Remillard & Lamb, 2005). We also found

significant differences by gender in the case of coping modalities. The

confrontational coping had higher values for boys (m

boys

= 6.84, m

girls

= 5.26

p < 0.01), while escape-avoiding is more frequently used by girls (m

girls

=

5.65, m

boys

= 4.78, p < 0.05).

Table 3. Mean, std. deviations and significances of differences for dependent variables

(self-esteem, perceived stress, coping style, aggression) depending on gender

Dependent variables Gender N Mean Std. dev. t p

Self-esteem

boys 33 29.48 4.79

10.71 0.001

girls 76 26.01 5.20

Perceived stress

boys 33 16.06 5.76

27.04 0.000

girls 76 22.50 6.01

Planned problem solving

boys 33 5.93 1.60

2.28 0.13

girls 76 5.42 1.66

Confrontational coping

boys 33 6.84 2.65

9.06 0.003

girls 76 5.26 2.46

Self-control

boys 33 3.69 2.40

0.21 0.64

girls 76 3.94 2.68

Positive reappraisal

boys 33 6.33 2.30

0.70 0.40

girls 76 5.96 2.05

Social support seeking

boys 33 3.42 1.34

0.27 0.60

girls 76 3.59 1.64

Distancing

boys 33 3.15 1.43

0.00 0.94

girls 76 3.17 1.46

Escape-avoiding

boys 33 4.78 2.10

4.37 0.03

girls 76 5.65 1.95

General level of aggression

(A/EX)

boys 33 49.24 8.24

0.41 0.52

girls 76 50.34 8.23

Level of repressed aggression

(A/I)

boys 33 18.57 4.36

0.15 0.69

girls 76 18.92 4.21

Level of expressed aggression

(A/O)

boys 33 18.97 5.00

0.01 0.91

girls 76 18.85 5.55

Table 4 contains data regarding differences of dependent variables

depending on the general level of aggression. The two groups were different

depending on the general level of aggression above or below the mean value

obtained for the whole participant group. Significant differences were found

concerning the coping modalities. Self-control is dominant for participants

characterized by higher aggression, while escape-avoidance shows a strong

relationship in cases of lower aggression.

Sndor Csibi, Monika Csibi 42

Table 4. Mean differences and their significances for participants with below or above mean

levels of general aggression

Dependent variables

Anger

Expression

N Mean Std. dev. t p

Self-esteem

above mean 54 27.41 6.04

0.66 0.51

below mean 55 26.73 4.52

Perceived stress

above mean 54 21.26 7.08

1.11 0.27

below mean 55 19.85 6.11

Planned problem solving

above mean 54 5.30 1.67

-1.78 0.08

below mean 55 5.85 1.61

Confrontational coping

above mean 54 5.59 2.68

-0.59 0.55

below mean 55 5.89 2.57

Self-control

above mean 54 4.69 2.77

3.40 0.00

below mean 55 3.07 2.15

Positive reappraisal

above mean 54 5.80 2.24

-1.35 0.18

below mean 55 6.35 1.99

Social support seeking

above mean 54 3.31 1.81

-1.52 0.13

below mean 55 3.76 1.23

Distancing

above mean 54 3.26 1.47

0.67 0.50

below mean 55 3.07 1.44

Escape-avoiding

above mean 54 5.00 2.07

-2.04 0.04

below mean 55 5.78 1.92

For outward expressed aggression we found significant differences

depending on the perceived level of stress (m

above mean

= 21.91, m

below mean

=

19.11, p < 0.05) which shows a higher level among participants with a higher

level of expressed aggression (see Table 5).

The predominant adoption of confrontational coping is associated

with lower values of expressed aggression. In the case of self-control as a

coping modality we obtained higher values among participants with higher

levels of expressed aggression (this factor includes items such as the tendency

to solve problems through emotional actions toward the source or cause of a

problem - consuming food in excess and drinking for reducing the tension of

the situation, and orientation of tension towards others). Social support

seeking is higher for participants with lower expressed aggression.

Table 5. Differences in levels of self-esteem, perceived stress and adopted coping modalities

depending on the levels of expressed aggression

Dependent variables

Level of

Anger Out

N Mean Std. dev. t p

Self-esteem

>= 19.00 56 26.23 6.02

-1.71 0.09

< 19.00 53 27.94 4.33

Perceived stress

>= 19.00 56 21.91 6.66

2.25 0.03

< 19.00 53 19.11 6.32

(table continues)

Psychosocial aspects of aggression in school environment 43

Table 5 (continued). Differences in levels of self-esteem, perceived stress and adopted coping

modalities depending on the levels of expressed aggression

Dependent variables

Level of

Anger Out

N Mean Std. dev. t p

Planned problem solving

above mean 56 5.39 1.74

-1.20 0.23

below mean 53 5.77 1.55

Confrontational coping

above mean 56 5.27 2.50

-1.97 0.05

below mean 53 6.25 2.67

Self-control

above mean 56 4.88 2.57

4.50 0.00

below mean 53 2.81 2.19

Positive reappraisal

above mean 56 6.34 2.19

1.35 0.18

below mean 53 5.79 2.04

Social support seeking

above mean 56 3.27 1.77

-1.91 0.06

below mean 53 3.83 1.24

Distancing

above mean 56 3.21 1.55

0.36 0.72

below mean 53 3.11 1.35

Escape-avoiding

above mean 56 5.14 1.99

-1.34 0.18

below mean 53 5.66 2.06

Table 6. Differences in levels of self-esteem, perceived stress and coping modalities

depending on the value of inside oriented aggression

Dependent variables

Level of

Anger In

N Mean Std dev. t p

Self-esteem

above mean 52 25.58 5.06

-2.88 0.00

below mean 57 28.42 5.22

Perceived stress

above mean 52 22.00 6.22

2.22 0.03

below mean 53 19.11 6.32

Planned problem solving

above mean 52 5.77 1.71

1.15 0.25

below mean 57 5.40 1.60

Confrontational coping

above mean 52 5.44 2.57

-1.15 0.25

below mean 57 6.02 2.66

Self-control

above mean 52 4.12 2.65

0.94 0.35

below mean 57 3.65 2.55

Positive reappraisal

above mean 52 6.46 1.98

1.84 0.07

below mean 57 5.72 2.21

Social support seeking

above mean 52 3.62 1.56

0.47 0.63

below mean 57 3.47 1.56

Distancing

above mean 52 3.08 1.56

-0.60 0.55

below mean 57 3.25 1.35

Escape-avoiding

above mean 52 5.79 1.89

1.96 0.05

below mean 57 5.04 2.10

Research shows that boys have significantly higher self-esteem than

girls. A possible explanation of these results is offered by the daily

experienced differences in the perceived level of stress. This might be higher

Sndor Csibi, Monika Csibi 44

in the case of girls, because of developmental specificities of adolescence,

related to the importance accorded by girls to self-and body image and also

generally self-appreciation.

Among boys the body image receives less attention, so their self-

image will show higher values together with a lower level of perceived stress.

(Zimmermann et al., 2003) Table 6 shows the differences in the level of self-

esteem and perceived stress depending on the inward orientation of

aggression. Self-esteem values are significantly lower and the level of

perceived stress is shown to be significantly higher for participants with high

inward oriented aggression.

Conclusions

Our study offered a detailed image regarding the school violence

phenomenon from the perspectives of individual, personality and social

factors.

The study allows for a deeper analysis of the specificities of the

teenage population, regarding the levels of expressed aggression and the

different modalities of manifestation, and also the adopted coping

modalities in stressful situations. The differences found for the variables

analyzed by us depending on the gender of the participants underlines the

impact of cultural and societal changes in present days. The differences

between boys and girls are not significant in the case of most variables

measured by our battery of instruments, teenagers showing the same

psychological particularities. Also we mentioned that the level of aggression

expression doesnt show significant differences between boys and girls.

Self-esteem and the level of perceived stress show significant

differences for girls and boys which denotes the characteristics of this specific

developmental period. Teenage in the case of girls is predominantly marked

by a special concern with their own body image, attention for the exterior

image and general self-image. Among boys these preoccupations are less

dominant. The perceived stress is also higher for girls, explainable exactly by

these preoccupations and concerns that are characteristic for their age.

Regarding the levels of aggression, these show significant differences

especially depending on adopted coping modalities, perceived stress and self-

esteem. We can conclude that aggressive behavior is strongly related to other

constructs within the personality. The mentalities and the tendencies within

teenagers living environments are determined by the social phenomenon

such as aggression. In the educational process the establishment of an

appropriate environment for the students development represents a priority.

Our results support the idea of planning and implementing of

prevention models in the field of health promotion among teenagers through

identified risk factors. Also, this can be useful for the elaboration of new

Psychosocial aspects of aggression in school environment 45

educational programs in the purpose of optimizing the school environment.

Our findings support the idea that programs which teach the skills needed for

constructive coping can be efficient in preventing the negative consequences

of stress among adolescents. More efficient coping skills are playing a

determinant role in healthy adjustment among adolescents, assuring more

perceived social support and less antisocial manifestations.

Our findings represent an important starting point for designing

preventive interventions or programs in the future, focusing on supporting the

adolescents to adopt effective ways of coping with stress and raise their self-

appreciation.

Our scientific approach allows educational professionals and

caregivers responsible with treatment networks to review the causes and

consequences of both pro-social and aggressive behavior.

References

Alsaker, F., & Olweus, D. (1986). Assessment of global negative self-

evaluations and perceived stability of self in Norwegian preadolescents

and adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 6, 269-278.

Aneshensel, C.S., & Phelan, J.C. (Eds.) (1999). Handbook Of The Sociology

Of Mental Health. New York: Kluver Academic.

Archer, J., & Coyne, S.M. (2005). An integrated review of indirect, relational,

and social aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3),

212-130.

Benbenishty, R., & Astor, R. (2005). School Violence in Context: Culture,

Neighborhood, Family, School and Gender. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Borum, R., & Verhaagen, D. (2006). Assessing and managing violence risk in

juveniles. New York: The Guilford Press.

Buda, B. (2004). A llek kzegszsgtana. Budapest: Animula Kiad.

Burton, L.A., Hafetz, J., & Henninger, D.(2007). Gender differences in

relational and physical aggression. Social Behavior and Personality,

35(1), 41-50.

Cohen, S., Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of

the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social

psychology of health: Claremont Symposium on applied social

psychology (pp. 31-67). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Cole, M., & Cole, S.R. (1997). Fejldsllektan. Budapest: Osiris Kiad.

Currie, C., &Williams, J.M. (2000). Self-esteem and physical development in

early adolescence: Pubertal timing and body image. The Journal of

Early Adolescence, 20(2), 129-149.

Furlong, M.J., Smith, C., & Bates, M.P. (2002). Further development of the

Multidimensional School Anger Inventory: Construct validation,

Sndor Csibi, Monika Csibi 46

extension to female adolescents, and preliminary norms. Journal of

Psychoeducational Assessment, 20, 46-65.

Hrdi I. (1992). A llek egszsgvdelme. Budapest, Springer Hungarica.

Hazebroek, J.F., Howells, K., & Day, A. (2001). Cognitive appraisals

associated with high trait anger. Personality and Individual Differences,

30(1): 31-45.

Ilu, P. (1994). Prosocial behavior antisocial behavior. In I. Radu (coord.),

Social Psychology, Cluj-Napoca: Exe.

Kaplan, H.I., Sadock, B.J., & Grebb, J.A. (1994). Synopsis of Psychiatry (7

th

ed.). Baltimore: Williams and Wikins.

Lable, D. (2007). Attachment with parents and peers in late adolescence:

Links with emotional competence and social behavior. Personality and

Individual Differences, 43(5), 1185-1197.

Langens, T.A., & Mrth, S. (2003). Repressive coping and the use of passive

and active coping strategies. Personality and Individual Differences,

35(2), 461-473.

Lansford, J.E., Malone, P.S.,Dodge, K.A., Crozier, J.C.,Pettit, G.S., &

Bates, J.E. (2006). A 12-Year prospective study of patterns of social

information processing problems and externalizing behaviors. Journal

of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34,715724.

Lazarus, R.S., & Folkman, S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process. Study

of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination.

Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 150-170.

Li, C.E., DiGiuseppe, R., & Froh, J. (2006). The roles of sex, gender, and

coping in adolescent depression. Adolescence, 41(163), 409-415.

Litman, J.A. (2006). The COPE inventory: Dimensionality and relationships

with approach- and avoidance-motives and positive and negative traits.

Personality and Individual Differences, 40(2), 273-284.

Lohaus, A., Vierhaus M., & Ball J. (2009). Parenting styles and health-related

behavior in childhood and early adolescence: Results of a longitudinal

study. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29, 449-475.

Luebbers, S., Downey, L.A., & Strongh, C. (2007). The development of an

adolescent measure of EI. Personality and Individual Differences,

42(6), 999-1009.

Lupu I., & Zanc I. (1999). Sociologie medical. Teorie i aplicaii. Iai:

Editura Polirom.

Ogden, J. (2007). Health Psychology. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Olh, A. (1995). Coping strategies among adolescents: A cross-cultural

study. Journal of Adolescence, 18(4), 491-512.

Olweus, D. (1984). Stability in aggressive and withdrawn, inhibited behavior

patterns. In R. Kaplan, V. Konecni, & R. Novaco (Eds.), Aggression in

children and youth (pp. 104-137). Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff.

Psychosocial aspects of aggression in school environment 47

Pik, B. (1997). Egyenltlensgek s egszsg: Hogyan befolysolja a

trsadalmi-gazdasgi helyzet a fiatalok egszsgi llapott?

Trsadalomkutats, 3-4, 219-233.

Pik, B. (2007). A pszichoszomatikus szemllet fontossga a csaldorvosi

gyakorlatban Hippocrates Csaldorvosi s foglalkozs-egszsggyi

folyirat, IX. 1., Szegedi Tudomnyegyetem.

Remillard, A.M., & Lamb, S. (2005). Adolescent girls coping with relational

aggression. Sex Roles, 53(3-4), 221-229.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton,

New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Rotariu, T., & Ilu, P. (2006). Ancheta sociologic i sondajul de opinie.

Iai: Editura Polirom.

Smits, D.J.M., & DeBoeck, P. (2007). From anger to verbal aggression:

Inhibition at different levels. Personality and Individual Differences,

43(1), 47-57.

Spielberger, C.D. (Ed.) (2004). Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology (vol I-

III). University of South Florida, USA: Elsevier Inc.

Spielberger, C.D., Johnson, E.H., Russell, S.F., Crane, R.H., & Worden, T.J.

(1985). The experience and expression of anger: Construction and

validation of an anger expression scale. In M.A. Chesney, & R.H.

Rosenman (Eds.) Anger and hostility in cardiovascular and behavioral

disorders (pp. 5-30). New York: Hemisphere / McGraw Hill.

Wrzesniewski K., & Chylinska J. (2007). Assessment of coping styles and

strategies with school-related stress. School Psychology International;

28, 179-194.

Zimmermann, P., Wittchen, H.U., Hofler, M., Pfister, H., Kessler, R.C., &

Lieb, R. (2003). Primary anxiety disorders and the development of

subsequent alcohol use disorders: A 4-year community study of

adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine, 33(7), 1211-

1222.

Zoccali, R., Muscatello, M.R.A., Bruno, A., Cedro, C., Pandolfo, G., &

Meduri, M. (2007). The role of defense mechanism in the modulation

of anger experience and expression: Gender differences and influence

on self-reported measures. Personality and Individual Differences,

43(6), 1426-1436.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Scraper SiteDokument3 SeitenScraper Sitelinda976Noch keine Bewertungen

- Blind DefenseDokument7 SeitenBlind DefensehadrienNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAARC and Pakistan, Challenges, ProspectDokument10 SeitenSAARC and Pakistan, Challenges, ProspectRiaz kingNoch keine Bewertungen

- May Galak Still This Is MyDokument26 SeitenMay Galak Still This Is MySamanthafeye Gwyneth ErmitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Progress Test 2Dokument5 SeitenProgress Test 2Marcin PiechotaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crossen For Sale On Market - 05.23.2019Dokument26 SeitenCrossen For Sale On Market - 05.23.2019Article LinksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study No. 8-Managing Floods in Metro ManilaDokument22 SeitenCase Study No. 8-Managing Floods in Metro ManilapicefeatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MONITORING Form LRCP Catch UpDokument2 SeitenMONITORING Form LRCP Catch Upramel i valenciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Security Awareness TrainingDokument95 SeitenSecurity Awareness TrainingChandra RaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 BT Annual ReportDokument236 Seiten2015 BT Annual ReportkernelexploitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manufacturing ConsentDokument3 SeitenManufacturing ConsentSaif Khalid100% (1)

- The Peace Report: Walking Together For Peace (Issue No. 2)Dokument26 SeitenThe Peace Report: Walking Together For Peace (Issue No. 2)Our MoveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Citrix WorkspaceDokument198 SeitenCitrix WorkspaceAMJAD KHANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Program Notes, Texts, and Translations For The Senior Recital of M. Evan Meisser, BartioneDokument10 SeitenProgram Notes, Texts, and Translations For The Senior Recital of M. Evan Meisser, Bartione123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bainbridge - Smith v. Van GorkomDokument33 SeitenBainbridge - Smith v. Van GorkomMiguel CasanovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DhakalDinesh AgricultureDokument364 SeitenDhakalDinesh AgriculturekendraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Little White Book of Hilmy Cader's Wisdom Strategic Reflections at One's Fingertip!Dokument8 SeitenLittle White Book of Hilmy Cader's Wisdom Strategic Reflections at One's Fingertip!Thavam RatnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wild Edible Plants As A Food Resource: Traditional KnowledgeDokument20 SeitenWild Edible Plants As A Food Resource: Traditional KnowledgeMikeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Puyat vs. Arco Amusement Co (Gaspar)Dokument2 SeitenPuyat vs. Arco Amusement Co (Gaspar)Maria Angela GasparNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Be Baptized in The Holy SpiritDokument2 SeitenHow To Be Baptized in The Holy SpiritFelipe SabinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- FineScale Modeler - September 2021Dokument60 SeitenFineScale Modeler - September 2021Vasile Pop100% (2)

- Bhagwanti's Resume (1) - 2Dokument1 SeiteBhagwanti's Resume (1) - 2muski rajputNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outline 2018: Cultivating Professionals With Knowledge and Humanity, Thereby Contributing To People S Well-BeingDokument34 SeitenOutline 2018: Cultivating Professionals With Knowledge and Humanity, Thereby Contributing To People S Well-BeingDd KNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21st Bomber Command Tactical Mission Report 40, OcrDokument60 Seiten21st Bomber Command Tactical Mission Report 40, OcrJapanAirRaids80% (5)

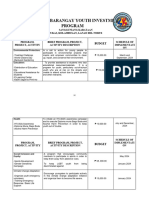

- Annual Barangay Youth Investment ProgramDokument4 SeitenAnnual Barangay Youth Investment ProgramBarangay MukasNoch keine Bewertungen

- (FINA1303) (2014) (F) Midterm Yq5j8 42714Dokument19 Seiten(FINA1303) (2014) (F) Midterm Yq5j8 42714sarah shanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intermarket AnaDokument7 SeitenIntermarket Anamanjunathaug3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Micro PPT FinalDokument39 SeitenMicro PPT FinalRyan Christopher PascualNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V CarlosDokument1 SeitePeople V CarlosBenBulacNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2020 2021 Important JudgementsDokument6 Seiten2020 2021 Important JudgementsRidam Saini100% (1)