Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Financial (Minimum Income) Requirement For Partner Visas

Hochgeladen von

sjplep0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

123 Ansichten18 SeitenThe financial (minimum income) requirement for partner visas - Commons Library Standard Note

http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN06724/the-financial-minimum-income-requirement-for-partner-visas

July 2014

Originaltitel

SN06724_jul2014

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThe financial (minimum income) requirement for partner visas - Commons Library Standard Note

http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN06724/the-financial-minimum-income-requirement-for-partner-visas

July 2014

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

123 Ansichten18 SeitenThe Financial (Minimum Income) Requirement For Partner Visas

Hochgeladen von

sjplepThe financial (minimum income) requirement for partner visas - Commons Library Standard Note

http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN06724/the-financial-minimum-income-requirement-for-partner-visas

July 2014

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 18

The financial (minimum income) requirement

for partner visas

Standard Note: SN/HA/06724

Last updated: 17 July 2014

Author: Melanie Gower

Section Home Affairs Section

In July 2012 controversial new maintenance funds requirements were introduced for

spouse/partner visas (affecting non-EEA national partners of British citizens, refugees and

people settled in the UK).

In effect, these require visa applicants to have available funds equivalent to a minimum gross

annual income of 18,600 (or higher in cases including non-EEA national dependent

children). In many cases only the British/settled sponsors employment income can be

considered, because the non-EEA nationals employment can only be taken into account if

they are already in the UK with permission to work.

Various migrants rights groups are campaigning against the financial requirement, which

they consider to be unfair, disproportionate and counter-productive to the Governments

intentions. In June 2013 a report by members of the APPG on Migration called for an

independent review of the requirement and its impact.

The Government has made some minor adjustments to the policy, but overall is satisfied that

it is operating as intended. It considers that the maintenance rules ensure that families are

able to support themselves and the migrant partners integration without being a burden on

the general taxpayer.

The lawfulness of the rules has been challenged in the courts. In July 2013 the High Court

found that certain factors in the way the financial requirement is applied represent a very

significant interference with British citizens and refugees rights. It suggested some

alternative ways of applying a financial requirement. However, on 11 July 2014 the Court of

Appeal overturned the High Courts decision, following an appeal brought by the

Government.

It is possible that a further appeal will be made to the Supreme Court. In the meantime, the

minimum income requirement remains in force. UK Visas and Immigration are resuming

consideration of applications that had been put on hold pending the outcome of the Court of

Appeal case.

This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties

and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. It should

not be relied upon as being up to date; the law or policies may have changed since it was last

updated; and it should not be relied upon as legal or professional advice or as a substitute for

it. A suitably qualified professional should be consulted if specific advice or information is

required.

This information is provided subject to our general terms and conditions which are available

online or may be provided on request in hard copy. Authors are available to discuss the

content of this briefing with Members and their staff, but not with the general public.

2

Contents

1 What are the financial (minimum income) rules? 2

1.1 Overview of the maintenance requirements before and after 9 July 2012 3

1.2 Summary of the rationale for the minimum income requirement 3

1.3 July 2012: Initial reactions to the policy 4

2 How the Rules are applied 6

2.1 Practical guidance for applicants 6

2.2 The scope for exemptions 6

Why dont the Rules affect European migrants? 7

2.3 Ways of satisfying the minimum income requirement 9

2.4 Some common criticisms of the rules, and counter-arguments 11

3 Opposition to the minimum income requirement 13

3.1 June 2013: APPG on Migrations inquiry into the impact of the new Rules 13

The Governments response: willing to consider some minor changes 14

4 Legal challenges 14

4.1 July 2013: High Court 14

4.2 Court of Appeal: July 2014 16

4.3 What happens next? 17

1 What are the financial (minimum income) rules?

The Immigration Rules requirements for leave to enter/remain as the non-EEA

1

national

partner (spouse/fianc(e), civil partner, prospective civil partner, unmarried or same-sex

partner) or dependent child of a British citizen or person who has Indefinite Leave, Refugee

Status or Humanitarian Protection in the UK changed on 9 July 2012, as part of a broader

package of changes to the Immigration Rules for family members.

2

One of the most significant changes was the introduction of a financial (minimum income)

threshold in order to satisfy a requirement to have adequate maintenance funds in place.

1

EEA European Economic Area (comprised of EU Member States plus Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein).

Swiss nationals have similar rights as EEA nationals.

2

HC 194 of 2012-13; summarised in Library Standard Note SN06353 Changes to Immigration Rules for family

members.

3

1.1 Overview of the maintenance requirements before and after 9 July 2012

Before 9 July 2012 Since 9 July 2012

Must demonstrate ability to adequately

accommodate and maintain the applicant

without recourse to public funds

With reference to Income Support levels (in

effect requiring a post-tax income of 5,500 per

year).

Must demonstrate available maintenance

funds equivalent to an income of at least

18,600 per year

(plus an extra 3,800 for one dependent child

and extra 2,400 for each additional child).

A variety of income sources could be

considered, for example:

- Sponsor and/or migrant partners

employment overseas and employment

prospects in the UK

- evidence of sufficient independent

means

- support from third parties (such as

family members)

Only income sources and evidence specified in

the Immigration Rules can be taken into

account, for example:

- Sponsors earnings in the UK, or

sponsors overseas earnings and

confirmed job offer in the UK

- migrant spouses employment income

(if they are in the UK with permission to

work)

Migrant spouses overseas employment

income or offers of employment in the UK, and

offers of third party support cannot be taken

into account.

The requirement was relevant when applying

for temporary leave to remain (after a two year

probationary period, the migrant partner could

apply for Indefinite Leave to Remain).

The requirement must be satisfied at two

application stages (during a five year

probationary period), and when applying for

Indefinite Leave to Remain.

1.2 Summary of the rationale for the minimum income requirement

The changes to the family migration rules (including the introduction of the minimum income

requirement) contribute to the Governments objective to reduce net migration levels from

hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands.

3

However the Government has emphasised

other policy objectives in explaining the rationale behind the minimum income requirement.

The Government considers that family migrants and their British-based sponsors should

have sufficient financial resources to be able to support themselves and enable the migrant

to participate in society without being a burden on the general taxpayer.

4

It changed the

maintenance requirements because it did not consider that the rules in place before July

2012 were sufficient for these objectives.

The minimum income threshold was set at 18,600 after the Government had considered

advice from its Migration Advisory Committee (MAC).

5

The MAC had recommended a

3

HC Deb 15 October 2012 c90W

4

HC Deb 11 June 2012 cc48-50

5

MAC, Review of the minimum income requirement for sponsorship under the family migration route,

November 2011

4

minimum gross sponsor income threshold of between 18,600 and 25,700 per year to

sponsor a partner. The different thresholds reflected different approaches to calculating

burden on the state. The MAC estimated that around 45% of applicants would fall short of

the lower threshold amount and 64% of applicants would not satisfy the upper threshold. The

MAC emphasised that its recommendations were purely based on economic considerations,

and did not take into account wider legal, social or moral issues related to family migration.

The MAC had identified 18,600 as the level of annual gross pay at which a couple would

not receive income-related benefits (assuming weekly rent of 100).

6

The Government has

said that it intends to review the level of the financial requirement annually, and that it may be

affected by the roll-out of Universal Credit.

7

The higher income requirement for sponsoring a child is intended to reflect the education

and other costs arising in such cases.

8

It applies at each application stage until the migrant

partner is granted permanent settlement, even if the dependent child turns 18 before this

time (unless they have been granted an immigration status in their own right).

9

It applies to

biological children, step-children and adopted children (in certain circumstances), and

children coming for the purpose of adoption who are subject to immigration control and

applying for limited leave to enter or remain under Appendix FM or the relevant paragraphs

of Part 8 of the Immigration Rules.

The financial requirement does not apply in respect of applications from a child who:

Is a British citizen (including an adopted child who acquires British citizenship);

Is an EEA national (except where a non-EEA spouse or partner is being accompanied

or joined by the EEA child of a former relationship who does not have a right to be

admitted to the UK under the Immigration (EEA) Regulations 2006);

Is settled in the UK or qualifies for indefinite leave to enter; or

Qualifies in a category under Part 8 or Appendix Armed Forces of the Immigration

Rules which is not subject to the financial requirement.

10

1.3 July 2012: Initial reactions to the policy

In Parliament

Responding to the Home Secretarys oral statement on 11 June 2012, Yvette Cooper,

Shadow Home Secretary, said that Labour supported strengthening the family immigration

rules to protect UK taxpayers. However, she cast doubt on the effectiveness of the

Governments approach:

We agree that stronger safeguards are needed for the taxpayer on family migration. If

people want to make this country their home, they should contribute and not be a

burden on public funds, but it is not clear that the best way to protect the taxpayer is to

focus solely on the sponsors salary. For example, in the current economic climate,

6

MAC, Review of the minimum income requirement for sponsorship under the family migration route,

November 2011, para 4.50

7

Home Office ,Statement of Intent: Family migration, 12 July 2012, para 80

8

Home Office ,Statement of Intent: Family migration, 12 July 2012, para 85

9

If the higher minimum income requirement continues to apply in respect of a child over 18, their income and

savings can be counted towards the requirement.

10

Home Office, Immigration Directorate Instructions, Chapter 8 Appendix FM (family members), Annex FM 1.7

Financial requirement, April 2014

5

someone on 40,000 today could lose their job next month, and then, of course, there

is no way to protect the taxpayer. The system does not take account of the foreign

partners income, which might have a differential impact on women. Will the Home

Secretary explain why the Government ruled out consulting on a bond that could have

been used to protect the taxpayer if someone needed public funds later on?

11

In response, the Home Secretary said that a bond would only be available to those people

who had capital and were able to put up a bond in the first place.

12

There was a mixed response from backbench Members to the Home Secretarys statement.

Some welcomed the changes, expressing hopes that they will tackle public concerns about

migrants (lack of) integration, sham marriages, and a lack of public confidence in the

immigration system.

13

Others were more critical; several Members highlighted examples of constituency cases that

would be unable to satisfy the minimum income threshold, and raised concerns that certain

groups would be disproportionately affected, such as young people, ethnic minorities, women

and people living in low-pay areas.

14

Fiona MacTaggart MP described the financial

requirement as a means test on family life, and contrasted it with the Governments

previously-stated family-friendly intentions.

15

NGOs, think-tanks, academia, etc.

Initial responses to the July 2012 changes from various migrants rights and civil liberties

organisations raised concerns that they would undermine, rather than enhance, migrant

family members prospects for integration.

Several highlighted particular concerns about the minimum income threshold and the effect it

was likely to have on groups more likely to be in low-paid employment.

The Family

Immigration Alliance, a forum for British/settled partners with experiences of sponsoring

partners applications, described the minimum income requirement as an act of obscene

discrimination, and argued that a precedent had been set where finance extends beyond

your quality of life, into your freedom to have a family at all.

16

The Migrants Rights Network warned that the changes would introduce additional hurdles

and costs for people, particularly lower earners and were likely to be viewed more widely as

unfair as their impacts on both migrants and British people are realised.

17

The Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) project, which is led by the British Council and

the Migration Policy Group think-tank, runs an interactive website comparing migrants

integration opportunities. It is based on analysis of immigration policies in over 30 countries.

A July 2012 blog post written by one of its Research Co-ordinators compared the UKs

partner visa rules with those in place in other countries, and concluded that The UK is slowly

becoming one of the least favourable places for non-EU residents and even its own citizens

to reunite with their families. It cautioned that the minimum income requirement might

undermine migrants integration prospects:

11

HC Deb 11 June 2012 cc50-1

12

HC Deb 11 June 2012 cc51-2

13

HC Deb 11 June 2012 c54, c57

14

HC Deb 11 June 2012 c54, c59

15

HC Deb 11 June 2012 c58

16

Family Immigration Alliance, Family Immigration Rules announced, 11 June 2012

17

Migrants Rights Network, Government changes to the family migration rules MRN e-briefing, June 2012

6

A high income threshold does not effectively promote long-term economic participation,

education, language learning, or fighting forced marriages. Instead, such requirements

have a disproportionate impact on limiting the number of family reunions, especially for

low-income and vulnerable groups. For many, family life becomes harder or impossible

through enforced separation. The OECD finds that every extra year that child spends

in country of origin and not in country of destination has a negative impact on their

language learning and societal adjustment. The OECDs conclusion is that family

reunion should be facilitated as soon as possible. British policy actors must strictly

scrutinise whether the new family reunion requirements exacerbate some of the very

problems that they are supposed to address.

18

On the other hand, Migration Watch issued a brief statement welcoming the changes, which

it considered would enhance family migrants prospects for integration.

19

2 How the Rules are applied

2.1 Practical guidance for applicants

The content (and format) of the Immigration Rules for family members of British/settled

persons who wish to join them in the UK are complex. They are spread between Part 8 and

Appendix FM and FM-SE of the Immigration Rules. Paragraphs A277 - A279 of the

Immigration Rules set out which parts of the Rules apply to pre- and post- 9 July 2012

spouse/fianc(e)/partner visa applicants.

The Family visas section on the GOV.UK website has general information for non-EEA

nationals about applying to join or remain in the UK with a British/settled partner. It also links

to the detailed policy guidance about the financial requirement and other eligibility criteria

which is used by UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) caseworkers when deciding

applications.

20

The Immigration Law Practitioners Association has produced several information sheets on

the changes to the family migration rules and related developments. As always, constituents

seeking advice specific to their circumstances should consult a suitably qualified

professional. The website of the Office of the Immigration Services Commissioner explains

about the regulation of immigration advisers and includes a useful online adviser finder.

2.2 The scope for exemptions

People granted leave to remain in a family immigration category before 9 July 2012 remain

covered by the Immigration Rules in force prior to that date. They are not subject to the

minimum income requirement.

21

For applications submitted on or after 9 July 2012, there is no scope to make exceptions to

the minimum income requirement where the Immigration Rules require that it is satisfied. It

applies when the migrant is first applying for temporary immigration leave to remain as a

18

MIPEX Blog, Cant Buy Me Love, 6 July 2012

19

Migration Watch, press release, Comment by Kiran Bali on Changes to Family Migration, 11 June 2012

20

Home Office, Immigration Directorate Instructions, Chapter 8 Appendix FM (family members). In particular,

Annex FM 1.7 Financial requirement and Annex 1.7a Maintenance discuss in detail how the minimum

income requirement is applied.

21

Further information can be found in Paragraphs A277 - A279 of the Immigration Rules and the Immigration

Directorate Instructions Chapter 8 family members transitional arrangements.

7

family member, when they apply to renew their temporary immigration status, and after five

years, when they become eligible to apply for Indefinite Leave to Remain.

However, the minimum income requirement does not apply if the UK-based sponsor is in

receipt of the following benefits:

Disability Living Allowance; Severe Disablement Allowance, Industrial Injuries

Disablement Benefit, Personal Independence Payment, Attendance Allowance, or

Carers Allowance.

Instead, they must demonstrate that they have adequate maintenance funds in place, in

line with the pre- July 2012 requirements.

22

However, the minimum income requirement will

apply in subsequent applications if the sponsors circumstances have changed. In March

2013 the Government confirmed that a review of the exemptions for sponsors who are

disabled or carers was ongoing and would be concluded shortly, and that affected persons

should not assume that the exemption would necessarily remain after April 2013.

23

However

these exemptions remain in place to date.

Applications sponsored by a member of HM Armed Forces personnel were initially exempt

from the minimum income requirement and continued to be assessed against the pre-9 July

2012 Immigration Rules requirements.

24

However, they became subject to the minimum

income requirement on 1 December 2013.

25

The main difference with non-Armed Forces

cases is that partners in Armed Forces cases are initially given leave to remain for five years

(rather than two and a half years as is the case for civilian cases). This affects the way in

which the couples cash savings are calculated, if they choose to rely on such savings in

order to meet the minimum income requirement.

People in receipt of certain payments related to service in HM Armed Forces (under the

Armed Forces Compensation Scheme or War Pensions Scheme) are exempt from the

minimum income requirement.

26

Why dont the Rules affect European migrants?

The rights of EU/EEA (hereafter, EEA)

27

nationals and their family members to come to the

UK derive from European law (specifically, Directive 2004/38/EC, often referred to as the

Citizens Directive or Free Movement of Persons Directive).

28

Non-EEA nationals, including family members of British citizens, are subject to the UKs

Immigration Rules. The Immigration Rules do not have to mirror European law, and indeed it

has long been the case that they have contained more restrictive eligibility criteria for family

members than European law. The financial requirement is the latest example of such a

difference - EU law does not specify a minimum income or specific level of resources that the

22

The guidance states applicants cannot rely on offers of support from third parties. Home Office, Immigration

Directorate Instructions, Chapter 8 Appendix FM (Family members), Annex FM section FM 1.7A, April 2013

23

HC 1039 of 2012-13

24

HC Deb 11 June 2012 c60

25

HC 803 of 2013-14; see also Home Office, Family members of HM Forces statement of intent: Changes to the

Immigration Rules from December 2013, 4 July 2013

26

HC 803 of 2013-14

27

EEA European Economic Area (comprised of EU Member States plus Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein.

28

Transposed into domestic legislation by the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2006, SI

2006/1003 (as amended). EEA and Swiss nationals have similar rights due to bilateral agreements with the

EU.

8

EEA national must have in order for their non-EEA family member to join them in the host

Member State.

Migration Watch has called for financial eligibility criteria to be applied to non-EEA national

family members of EU citizens living in the UK in a similar way as is the case under the

Immigration Rules.

29

Chris Bryant, then Shadow Immigration Minister, also described the

difference between EU law and the UKs Immigration Rules as a significant loophole and

suggested that it requires concerted EU action.

30

Although the UK is an EU Member State, EEA citizens are not generally considered to be

exercising free movement rights granted by European law whilst they are living in their own

country, and therefore their non-EEA family members cannot join them using the provisions

in EU free movement law. However, following the European Court of Justices decision in

the Surinder Singh case, an exception is made if the EEA citizen has been exercising their

free movement rights as a worker or self-employed person in another EU Member State but

then wishes to return to their country of nationality with their family member.

31

In these

circumstances the non-EEA national spouse may be treated as the family member of an EEA

citizen in accordance with EU free movement law, rather than being subject to the countrys

national immigration law.

32

There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that some British citizens - particularly those who

cannot satisfy the UKs visa requirements - are deciding to temporarily live and work in

another EU Member State, in order to be able to return to the UK with their non-EU partner

under European law instead of applying for a visa under the Immigration Rules.

33

In December 2013 the Government amended the regulations transposing the Free

Movement of Persons Directive into UK law, by requiring that the British citizen had

transferred the centre of their life to another Member State in order to benefit from Singh.

34

The Explanatory Memorandum to the SI explained:

7.11 (...) Whether or not a British citizen has transferred the centre of their life to

another member State will be assessed by reference to a number of criteria, including

the length of residence, the degree of integration and whether or not the British citizen

has moved their principal residence to that other member State.

The changes were made in order to ensure that there has been a genuine and effective use

of free movement rights in the other member State before such rights may apply by analogy

upon return to the UK. One of the intended effects was preventing abuse by those British

citizens who move temporarily to another member State in order to circumvent the

requirements of the usual immigration rules for their family members upon return to the UK.

The EU Rights Clinic at the University of Kent has posted some commentary on the

change.

35

29

Migration Watch briefing 4.22, Family permits for EU citizens in Britain, 9 May 2013

30

Labour.org.uk, Effective action on immigration not offensive gimmicks - Chris Bryant, 12 August 2013

31

ECJ, C-370/90

32

UKBA, Entry Clearance Guidance, EUN2,14 - EEA family permits, (undated; accessed on 6 September 2013)

33

BBC News [online], The Britons leaving the UK to get their relatives in, 25 June 2013

34

Immigration (European Economic Area) (Amendment) (No.2) Regulations 2013, SI 3032/2013

35

EU Rights Clinic Blog, UK Changes Rules on Surinder Singh route, 8 December 2013

9

2.3 Ways of satisfying the minimum income requirement

Only income from sources that are specified in Appendix FM-SE of the Immigration Rules

can be considered when assessing whether an application satisfies the minimum income

requirement. The Home Offices policy guidance on the financial requirement summarises

the five acceptable income sources:

Income from salaried or non-salaried employment of the partner (and/or the

applicant if they are in the UK with permission to work). This is referred to as

Category A or Category B, depending on the employment history. See section

5 of this guidance.

Non-employment income, e.g. income from property rental or dividends from

shares. This is referred to as Category C. See section 6 of this guidance.

Cash savings of the applicants partner and/or the applicant, above 16,000,

held by the partner and/or the applicant for at least 6 months and under their

control. This is referred to as Category D. See section 7 of this guidance.

State (UK or foreign) or private pension of the applicants partner and/or the

applicant. This is referred to as Category E. See section 8 of this guidance.

Income from self-employment, and income as a director of a specified limited

company in the UK, of the partner (and/or the applicant if they are in the UK

with permission to work). This is referred to as Category F or Category G,

depending on which financial year(s) is or are being relied upon. See section 9

of this guidance.

36

Various combinations of these sources are allowed in order to meet the minimum income

requirement, however certain combinations are not. For example, cash savings can be

combined with income from salaried and non-salaried employment in certain circumstances,

but they cannot be combined with income from self-employment.

There are specific criteria attached to each of these permitted income sources. For example,

as the descriptions for categories A and B indicate, the migrant applicants employment

income can only be taken into account once they are in the UK with permission to work -

their overseas employment income, or prospective earnings from a job offer in the UK, will

not be considered. Therefore, only the sponsor (i.e. the British/settled partner)s employment

income is considered if the applicant is not already living and working in the UK.

Furthermore,

If the sponsor is in the UK and relying on their employment income, they must be in

employment at the point of application (with a gross annual salary which meets the

financial requirement alone or combined with other permitted sources) and either:

o have been so continuously for the previous six months or

o if employed for less than six months, have also received over the previous 12

months the level of income required through gross salaried income and/or

other permitted sources.

36

Home Office, Immigration Directorate Instructions, Chapter 8 Appendix FM (Family members), Annex FM 1.7

(accessed on 16 July 2014)

10

If the sponsor has been living overseas and is returning to the UK with the applicant,

they must have a verifiable job offer or signed contract of employment to start work

within three months of their return (with an annual salary which is sufficient to meet

the financial requirement on its own or in conjunction with other permitted sources).

They must also either:

o be in employment overseas at the point of application (with a gross annual

salary which meets the financial requirement alone or in combination with

other permitted sources) and have been so continuously for at least the

previous six months; or

o have received the level of income required over the previous 12 months

through gross salaried income and/or other permitted sources.

The Immigration Rules and associated policy guidance also specify what pieces of evidence

must be submitted in order to demonstrate income from each of the permitted sources. For

example, an application relying on income from salaried employment must provide:

Wage slips covering 6 or 12 months prior to the date of the application (depending on

the length of employment); and

A letter from the employer(s) who issued the wage slips, confirming the person's

employment and gross annual salary; the length of their employment; the period over

which they have been or were paid the level of salary relied upon in the application;

and the type of employment (permanent, fixed-term contract or agency); and

Personal bank statements corresponding to the same period(s) as the wage slips,

showing that the salary has been paid into an account in the name of the person or in

the name of the person and their partner jointly.

The guidance states that in addition, P60(s) for the relevant period(s) of employment (if

issued) and a signed contract(s) of employment may also be submitted or requested by the

decision-maker, in respect of paid employment in the UK.

If cash savings are being relied on to satisfy the minimum income requirement, they must

have been held by the applicant, their partner or both jointly and under their control, and for

at least the six months prior to the date of application. The first 16,000 in cash savings are

not taken into account. This is because 16,000 is the level at which a person generally

ceases to be eligible for income-related benefits.

When applying for temporary leave to remain, the amount of cash savings that can be

counted towards the income requirement is calculated by dividing the amount of savings over

16,000 by 2.5 (this is equivalent to the number of years of temporary leave being applied

for). When applying for Indefinite Leave to Remain (after five years), all cash savings over

16,000 can be considered.

In practice, therefore, when applying for temporary leave as a partner:

62,500 in cash savings is required if no other income sources are being used to

meet the income requirement: (62,500-16,000) / 2.5 = 18,600

11

17,500 in cash savings is required if the sponsors income is 18,000, in order to

make up the 600 shortfall: (17,500-16,000) / 2.5 = 600

37

Some changes have been made to the Immigration Rules and policy guidance, in response

to calls for greater flexibility.

38

For example, some flexibility was introduced about the length

of time that cash savings arising from the realisation of an asset must be held, and it has

been confirmed that academic stipends or maintenance grants can be counted as income. It

has also been confirmed that caseworkers have the discretion to contact applicants to

request further information or documentation before making a decision on the application.

2.4 Some common criticisms of the rules, and counter-arguments

39

Is the threshold set too high?

UKVI (previously UKBA) case file analysis cited in the Home Offices Impact Assessment

suggested that around 45% of sponsors sampled were not in employment or earned less that

18,600 per annum. It also noted that the Annual Survey for Hourly Earnings indicated that

around 40 - 45% of UK residents earn less than 18,600. The minimum wage for a 40 hour

week for workers over 21 is currently equivalent to 13,124 per annum.

The Government has said that 18,600 is the income level at which a couple generally cease

to be eligible for income-related benefits. Its Impact Assessment suggested that a proportion

of people earning less than this would still be eligible to sponsor a partner visa - for example,

if they are in receipt of certain welfare benefits and therefore exempt from the requirement, or

if they and their partner have appropriate sources of non-employment income, or if they

increase their working hours or skills in order to earn a higher income.

Should the income threshold take regional differences into account?

Some have argued that there should be variable income thresholds to reflect differences in

wages and living costs across the UK (and overseas). Research published in June 2014 by

the Migrants Rights Network, which opposes the minimum income requirement, found 74

parliamentary constituencies where the 18,600 income requirement was higher than the

earnings of 50% or more of all residents in employment.

40

The MACs report to the Government did not consider these arguments in detail, but said that

it did not see a clear case for differentiation.

41

The Government shares the MACs concerns.

It believes that a single national threshold provides clarity and simplicity for applicants and

Home Office staff. It has also pointed out that the benefit system is not regionalised (with the

exception of housing benefits) in spite of regional differences in wages and costs of living.

The Government also argues that regional thresholds would be difficult to enforce, since

there would be a risk that some sponsors would temporarily move to an area with a lower

income threshold until the visa had been granted. Another concern is that families who had

to move for other reasons, or who lived in a relatively poor part of an affluent region (or vice

versa) might be unfairly dis/advantaged by differential thresholds.

37

The amounts may differ for family members of Armed Forces sponsors.

38

HC 1039 of 2012-13; HC 628 of 2013-14

39

For relevant sources see, for example, APPG Migration, Report of the Inquiry into new Family Migration

Rules, June 2013; HC Deb 19 June 2013 cc254-279WH; HL Deb 4 July 2013 cc1385-1406; Home Office

Impact Assessment IA No. HO0065 Changes to family migration rules, 12 June 2012; Home Office, Letter

from Lord Taylor of Holbeach to Baroness Hamwee, 5 August 2013, DEP2013-1434

40

MRN, The family migration income threshold: Pricing UK workers out of a family life, June 2014

41

MAC, Review of the minimum income requirement for sponsorship under the family migration route,

November 2011, paras 4.43-4.44

12

Are the evidential requirements unduly restrictive?

Although the Government has made some minor adjustments to the Rules since July 2012,

critics have highlighted examples of inflexibility in the way in which the minimum income

threshold is assessed. For example, there is no scope to reduce or waive the minimum

income threshold if a couple has reduced costs of living due to offers of third-party support

(such as accommodation provided by relatives), or to take into account an applicants high

earnings overseas or job offers in the UK, or cash savings below 16,000 or which have not

been held for six months.

The Government has argued that offers of third party support are vulnerable to changes in

circumstances or relationships. Furthermore, it argues that employment overseas,

employment prospects in the UK or promises of employment are no guarantee to getting a

job. It has suggested that if a migrant partner has a confirmed job offer in the UK, they could

apply under Tier 2 of the points-based system instead, although it has acknowledged that the

eligibility criteria for Tier 2 visas would rule this out in some cases. It also argues that there

are some permitted income sources which allow the migrant partners non-employment

income to be taken into account.

It has said that at least six months evidence of cash savings is necessary in order to ensure

that the funds are genuinely under the couples control and not the product of a short-term

loan, and that it is reasonable to expect applicants to organise their finances in accordance

with the requirements of the Immigration Rules.

Is the minimum income requirement saving money or leading to unforeseen costs?

Some families affected by the rules have argued that they undermine the Governments

objectives to promote self-sufficiency and family unity. For example, if a British citizen

returns to the UK to find a job at the appropriate minimum income threshold, they will need to

work for at least six months before they can sponsor the application. There have been

accounts of families enduring prolonged periods of separation due to not being able to satisfy

the minimum income requirement. It has also been argued that some families have needed

recourse to public funds, which would not have been necessary if the migrant partner was

able to join them in the UK and share the sponsors work and caring responsibilities.

The Home Offices Impact Assessment estimated the minimum income requirement would

bring an overall net benefit of 660million over ten years. This estimate included

consideration of the reduction in direct tax revenue from working migrant partners, and

savings in healthcare, education and welfare.

Middlesex University has argued that the Government did not take into account the loss of

the wider economic benefits of migrant partners economic activity. Using an alternative

model for calculations based on the figures in the Governments Impact Assessment, it has

suggested that the changes could cost the UK 850million over ten years.

42

The

Government does not accept these conclusions.

43

42

Middlesex University, The fiscal implications of the minimum income requirement: what does the evidence tell

us? July 2013

43

HL Deb 24 July 2013 cWA248

13

3 Opposition to the minimum income requirement

Various civil society organisations are campaigning against the minimum income

requirement see, for example, the websites of the Joint Council for the Welfare of

Immigrants, Migrants Rights Network, BritCits and the Family Immigration Alliance.

44

3.1 June 2013: APPG on Migrations inquiry into the impact of the new Rules

In June 2013 a committee of members of the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on

Migration

45

published a report of their inquiry into the impact of the family migration rules

changes.

46

The inquiry focussed on the impact of the minimum income requirement for

partner visas, and other changes affecting adult dependent relatives (not discussed in this

note). Over 280 submissions of evidence were received, over half of which were from

families affected by the rules.

47

The report recommended that the Government commission an independent review of the

minimum income requirement and its impacts, to consider whether the level of the income

requirement and the range of permitted income sources represent an appropriate balance

between the different interests in this area.

48

The Government rejected this idea, stating that

it was satisfied that the family Immigration Rules are operating as intended but that it would

keep their impact under review.

49

The committee had found that the minimum income requirement had resulted in some British

citizens and permanent residents being separated from their non-EEA national

partner/children, including sponsors who were in full-time employment and earning above the

minimum wage. Submissions of evidence suggested that sponsors based outside London

and the South East, and in lower-earning sections of the population (including women, young

adults, the elderly and some ethnic minority groups) had been particularly affected. It

received evidence suggesting that there had been some unforeseen costs to the public purse

as a result of non-EEA national partners exclusion from the UK, such as UK-based sponsors

having increased recourse to welfare benefits, and a loss of potential tax revenue from non-

EEA partners future earnings.

In addition, the committee contended that the limited range of income sources that can be

taken into account appeared to have delayed or prevented some families from living together

in the UK, including cases involving high income/high net worth individuals.

The UKs four Childrens Commissioners endorsed the report, and particularly its

recommendation that the Immigration Rules should ....ensure that children are supported to

live with their parents in the UK where their best interests require this.

50

In June 2013 they

published a briefing which summarised the UKs obligations in domestic and international law

44

See, for example, JCWI website United by love, divided by Theresa May (accessed 6 September 2013);

MRN briefing, What are the consequences of minimum income requirement for family migrants in the UK?,

28 July 2013; The family migration income threshold: Pricing UK workers out of a family life, June 2014

45

Migrants Rights Network provides the secretariat to the APPG on Migration.

46

APPG Migration, Report of the Inquiry into new Family Migration Rules, June 2013

47

APPG on Migration, Family inquiry (undated; accessed on 6 September 2013)

48

APPG Migration, Report of the Inquiry into new Family Migration Rules, June 2013, p.35

49

HL Deb 26 June 2013 ccWA147-8

50

APPG Migration, Report of the Inquiry into new Family Migration Rules, June 2013, p.35

14

and their concerns about how the new family migration rules have impacted on childrens

rights to family life.

51

The Governments response: willing to consider some minor changes

Following the publication of the APPGs report, a related Westminster Hall debate about the

effects of the new family migration rules took place on 19 June 2013.

52

A similar debate took

place in the House of Lords on 4 July 2013.

53

During the debate in the Commons, Mark Harper, then Minister for Immigration, indicated a

willingness to consider whether there was scope to introduce greater flexibility in the

evidential requirements, such as in cases where the migrant partner has a job offer:

I am prepared to consider whether we can put in place some rules that are not

vulnerable to abuse. The best argument was the example of a couple, one of whom

would be working here but was insufficiently skilled to meet the criteria to apply under

the tier 2 scheme. (...) If people can get here under a tier 2 visa, that is fine. However,

clearly there are people who could make a contribution but could not meet those

criteria.

The situation is not quite as straightforward as people say, because we must guard

against abuse. If all people have to do is to show a piece of paper saying that they

have a job offer, I know from the number of cases I have seen that it will not be long

before people are setting up vague companies and offering jobs that do not exist.

There must be a way of putting in place processes that do not lead to abuse. I think

that is worth doing and I am prepared to go away and do so.

54

In a subsequent Westminster Hall debate on the financial requirement in September 2013,

the Minister confirmed that the Home Office was considering how the Rules could take a

migrant spouses job offer into account, and that it remained willing to consider arguments for

further changes where unintended consequences of the Rules are brought to its attention.

55

Some minor changes to the evidential requirements came into effect on 1 October 2013,

such as allowing for electronic bank statements to be submitted and for cash savings to

include proceeds from a sale of property.

56

The changes also included allowing sponsors

returning to work in the UK to count future on-target earnings towards the financial

requirement.

4 Legal challenges

4.1 July 2013: High Court

Two British citizens and a refugee, who wish to sponsor their non-EEA national partners to

join them in the UK but cannot satisfy the financial requirement, have challenged the

maintenance requirements through judicial review.

51

Childrens Commissioners, The UK Childrens Commissioners briefing on the All-Party Parliamentary Group

on Migration: Report of the Inquiry into the New Family Migration Rules, June 2013

52

HC Deb 19 June 2013 cc254-279WH

53

HL Deb 4 July 2013 cc1385-1406

54

HC Deb 19 June 2013 c277-8WH

55

HC Deb 9 September 2013 c808-810WH

56

HC 628 of 2013-14

15

Judgment was given in the High Court on 5 July 2013.

57

The rules were not found to be

unlawfully discriminatory, for example against female sponsors or those living outside

London and the South-East. Nor were they deemed to be unlawful on the grounds that they

failed to make an over-riding accommodation of the best interests of the child.

Furthermore, the court found that the rules had legitimate aims (to promote the economic

and social welfare of the whole community, facilitate integration, and provide clarity and

transparency), and were rationally connected with those. It determined that the Home

Secretary was justified in concluding that greater maintenance resources were needed in

pursuit of these aims than the Immigration Rules had previously required.

It also recognised that there might be legitimate and proportionate restrictions on the

admission of foreign spouses, and that financial self-sufficiency of a foreign family is a

legitimate consideration.

However, the court highlighted several features of the maintenance requirements since July

2012 that led it to believe that that the scale of the interference with British citizens rights is

very significant. It concluded that, when applied to cases sponsored by a British citizen or

refugee, the Immigration Rules relating to the 18,600 minimum income requirement were so

onerous as to be an unjustified and disproportionate interference with a genuine spousal

relationship:

123. Although there may be sound reasons in favour of some of the individual

requirements taken in isolation, I conclude that when applied to either recognised

refugees or British citizens the combination of more than one of the following five

features of the rules to be so onerous in effect as to be an unjustified and

disproportionate interference with a genuine spousal relationship. In particular that it

likely to be the case where the minimum income requirement is combined with one or

more than one of the other requirements discussed below. The consequences are so

excessive in impact as to be beyond a reasonable means of giving effect to the

legitimate aim.

124. The five features are:

i. The setting of the minimum income level to be provided by the sponsor at above the

13,400 level identified by the Migration Advisory Committee as the lowest

maintenance threshold under the benefits and net fiscal approach (Conclusion 5.3).

Such a level would be close to the adult minimum wage for a 40 hour week. Further

the claimants have shown through by their experts that of the 422 occupations listed in

the 2011 UK Earnings Index, only 301 were above the 18,600 threshold.

ii. The requirement of 16,000 before savings can be said to contribute to rectify an

income shortfall.

iii. The use of a 30 month period for forward income projection, as opposed to a twelve

month period that could be applied in a borderline case of ability to maintain.

iv. The disregard of even credible and reliable evidence of undertakings of third party

support effected by deed and supported by evidence of ability to fund.

v. The disregard of the spouse's own earning capacity during the thirty month period of

initial entry.

57

MM & Ors v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2013] EWHC 1900 (Admin)

16

Mr Justice Blake considered that there was a wider margin of appreciation available to the

Home Secretary in cases involving a non-EEA national sponsor, observing that case law has

generally found that there is no particular reason why non-EEA nationals preferred place of

residence must be facilitated by the Immigration Rules. However, the position is different for

refugees and British citizens. British citizens have a fundamental right of constitutional

significance recognised by the common law to reside in their own country, which is

interfered with if their foreign spouse is excluded from the UK. Refugees are also in a

different position to other non-EEA nationals, since they are unable to reside in their country

of nationality, and are compelled to reside in a host state.

The determination went on to suggest some less intrusive ways in which a financial

requirement might be applied:

147. There are a variety of less intrusive responses available. They include:

i. reducing the minimum income required of the sponsor alone to 13,500; or

thereabouts;

ii. permitting any savings over the 1,000 that may be spent on processing the

application itself to be used to supplement the income figure;

iii. permitting account to be taken of the earning capacity of the spouse after entry or

the satisfactorily supported maintenance undertakings of third parties;

iv. reducing to twelve months the period for which the pre estimate of financial viability

is assessed.

However, the Rules were not struck down as unlawful in general, and Mr Justice Blake noted

that it was up to the Home Secretary to consider whether to make changes in light of the

judgment.

The Home Office immediately suspended consideration of applications whilst it assessed the

implications of the judgment.

58

It subsequently appealed against the outcome.

59

A letter from

Lord Taylor of Holbeach, Home Office Minister, summarised the Governments position:

... matters of public policy, including the detail of how the income threshold should

operate, are for the Government and Parliament to determine, not the Courts. We also

believe that the detailed requirements of the policy, which reflect extensive consultation

and consideration, are proportionate to its aims.

60

Consideration of applications that fell for refusal solely because they did not satisfy the

financial requirement continued to be suspended pending the outcome of the Home Offices

appeal. However, processing continued as normal for applications that could satisfy the

financial requirement, or that fell for refusal for other reasons.

61

4.2 Court of Appeal: July 2014

The Court of Appeal hearing took place over 4-5 March 2014 and judgment was given on 11

July.

62

The Court of Appeal overturned the High Courts decision.

58

UKBA update, Minimum income threshold for family migrants, 5 July 2013

59

UKBA update, Minimum income threshold for family migrants, 26 July 2013

60

Home Office, Letter from Lord Taylor of Holbeach to Baroness Hamwee, 5 August 2013, DEP2013-1434

61

UKBA update, Minimum income threshold for family migrants, 26 July 2013

62

MM v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2014] EWCA Civ 985

17

Its findings included the following points:

149. So the key question is: to what extent should the court substitute its own view of

what, as a general policy, is the appropriate level of income for that rationally chosen

as a matter of policy by the executive, which is headed by ministers who are

democratically accountable? Blake J suggested, at [147], that there were "less

intrusive responses" that were available and he gave examples. What he meant by

this is that, in his view, these "less intrusive responses" constituted what was "no more

than necessary" to accomplish the policy aim and, in his view, constituted a fair

balance between the rights of the individual and the interests of the community. I

appreciate that proportionality has to be judged "objectively by the court". However, in

making this objective judgment appropriate weight has to be given to the judgment of

the Secretary of State, particularly where, as here, she has acted on the results of

independent research and wide consultations.

()

151. I am very conscious of the evidence submitted by the claimants to demonstrate

how the new MIR will have an impact on particular groups and, in particular, the

evidence that only 301 occupations out of 422 listed in the 2011 UK Earnings data had

average annual earnings over 18,600. But, given the work that was done on behalf of

the Secretary of State to analyse the effect of the immigration of non-EEA partners

and dependent children on the benefits system, the level of income needed to

minimise dependence on the state for families where non-EEA partners enter the UK

and what I regard as a rational conclusion on the link between better income and

greater chances of integration, my conclusion is that the Secretary of State's judgment

cannot be impugned. She has discharged the burden of demonstrating that the

interference was both the minimum necessary and strikes a fair balance between the

interests of the groups concerned and the community in general. Individuals will have

different views on what constitutes the minimum income requirements needed to

accomplish the stated policy aims. In my judgment it is not the court's job to impose its

own view unless, objectively judged, the levels chosen are to be characterised as

irrational, or inherently unjust or inherently unfair. In my view they cannot be.

63

In a news story published on GOV.UK on 11 July, James Brokenshire, Immigration and

Security Minister, welcomed the determination and defended the minimum income threshold:

We welcome those who wish to make a life in the UK with their family, work hard and

make a contribution, but family life must not be established in the UK at the taxpayers

expense and family migrants must be able to integrate.

The minimum income threshold to sponsor family migrants is delivering these

objectives and this judgment recognises the important public interest it serves.

64

4.3 What happens next?

The 18,600 minimum income requirement remains in force, and consideration of the cases

that had been put on hold pending the Court of Appeal determination thought to be around

4,000 will resume.

65

63

MM v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2014] EWCA Civ 985 (footnotes omitted)

64

Gov.uk, News story, Home Office wins judgment on minimum income threshold, 11 July 2014

65

Gov.uk, News story, Home Office wins judgment on minimum income threshold, 11 July 2014. As at 31

March 2014, 3,134 visa applications submitted overseas and 507 applications made in the UK were on hold:

Gov.uk, Transparency data, Number of settlement applications from non-EEA partners on hold pending the

results of a judicial review, (accessed on 11 July 2014)

18

An update posted on the website of No5 Chambers (some of whose barristers were

instructed in the appeals) discusses the possibility of a further appeal to the Supreme Court:

The Court of Appeal has held that the requirements are lawful. The court reached this

conclusion essentially on the basis that it was not for the court to analyse the basis of

the Secretary of States decision to introduce such requirements into the immigration

rules which are merely statements of administrative policy. The test adopted by the

court is the same as that which it adopted in Bibi [2013] EWCA Civ 322 (the case

concerning the English language requirement), namely that it is enough that the

Secretary of State should have a rational belief that the policy embodied in the

requirements will achieve the identified aim. This is an extremely restrained form of

judicial review and suggests a lack of willingness to interfere with governmental

decisions. This test seems to conflict with the approach adopted by the Supreme Court

in cases such as Baiai [2008] UKHL 53 and Quila [2011] UKSC 45 where the court

adopted a rigorous analysis in assessing the evidence and used a test requiring the

Secretary of State to show an objective justification.

The Supreme Court has already granted permission to appeal in Bibi on arguments

which include the argument that the test of a mere rational belief is wrong. It is likely

that the present case will also proceed to the Supreme Court. Whereas Mr Justice

Blakes decision had properly considered the detailed evidence provided by the

claimants lawyers, the Court of Appeal barely considered it.

66

The update goes on to consider the possible implications of the Court of Appeals

determination for applicants who cannot satisfy the financial requirement. In particular, it

notes that there remains scope to successfully argue individual cases under Article 8 of the

European Convention on Human Rights (right to private and family life):

Applicants may however still succeed under Article 8 of the European Convention of

Human Rights even if they cannot satisfy the minimum income requirements under the

rules. ()

The Court of Appeal did not treat the rules on minimum income requirements as

constituting a complete code for Article 8 purposes such that there was no need to

consider article 8 separately. Indeed, that was not the Secretary of States position.

The Court of Appeal also noted the Guidance which had initially been produced in a

draft form (only on the fourth day of the hearing before Mr Justice Blake) and the

Guidance which had then been promulgated in final form after that hearing. That final

Guidance directs caseworkers first to consider applications under the rules and, if the

applicant does not meet the requirement of the rules, to move onto a second stage.

Under that second stage caseworkers are required to consider whether, based on an

overall consideration of the facts of the case, there are exceptional circumstances

which mean refusal of the application would result in unjustifiably harsh consequences

for the individual or their family such that refusal would not be proportionate under

Article 8. If there are such exceptional circumstances, leave outside the rules should

be granted, if not, the application should be refused.

66

No5 Chambers, Court of Appeal rules on family migration and the minimum income requirement, 11 June

2014

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Changes To Immigration Rules For Family MembersDokument16 SeitenChanges To Immigration Rules For Family MemberssjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- BritCits FAQDokument15 SeitenBritCits FAQBritCits100% (2)

- Family Members Under Appendix FM of The Immigration Rules UkDokument23 SeitenFamily Members Under Appendix FM of The Immigration Rules UkAmir FarooquiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Migration Inquiry: Joint Council For The Welfare of ImmigrantsDokument6 SeitenFamily Migration Inquiry: Joint Council For The Welfare of ImmigrantssjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benefits Update May 2015Dokument8 SeitenBenefits Update May 2015sawweNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Immigration RulesDokument17 SeitenFamily Immigration RulesBritCitsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Private Client Practice: An Expert Guide, 2nd editionVon EverandPrivate Client Practice: An Expert Guide, 2nd editionNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADR Judgment - 16.04.20 Approved Transcript High CourtDokument12 SeitenADR Judgment - 16.04.20 Approved Transcript High CourtBritCitsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taxe FiscaleDokument7 SeitenTaxe FiscaleCristina CiobanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- UK EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Only B.II) - FinalDokument4 SeitenUK EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Only B.II) - Finaltunca_olcaytoNoch keine Bewertungen

- GEPF Inside Booklet 1Dokument34 SeitenGEPF Inside Booklet 1Kevin CreaseyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uc Draft Regs 2012 MemorandumDokument59 SeitenUc Draft Regs 2012 MemorandumPaul SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- NewsletterDokument4 SeitenNewsletterMRSN1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Uk 11545458 Adv Introduction 18326968 PDFDokument6 SeitenUk 11545458 Adv Introduction 18326968 PDFOlgica StefanovskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HMRC 6Dokument86 SeitenHMRC 6cucumucuNoch keine Bewertungen

- SB 12-21 Welfare Reform (Further Provision) (Scotland) Bill (565KB PDFDokument20 SeitenSB 12-21 Welfare Reform (Further Provision) (Scotland) Bill (565KB PDFlukaszatcrushNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Uneven Impact of Welfare Reform: The Financial Losses To Places and PeopleDokument92 SeitenThe Uneven Impact of Welfare Reform: The Financial Losses To Places and PeopleOxfamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Call For EvidenceDokument11 SeitenCall For EvidenceKah Khen ChaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- bn38 2022Dokument27 Seitenbn38 2022janove9536Noch keine Bewertungen

- Health Care Reform Act: Critical Tax and Insurance RamificationsVon EverandHealth Care Reform Act: Critical Tax and Insurance RamificationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Housing Migrant Workers and RefugeesDokument58 SeitenHousing Migrant Workers and RefugeesSFLDNoch keine Bewertungen

- NL EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Only B.II) - FinalDokument4 SeitenNL EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Only B.II) - FinaltrnrlibalyemebtsabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sponsorship Fact SheetDokument2 SeitenSponsorship Fact SheetNabendu SahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MM and Ors Case OverviewDokument25 SeitenMM and Ors Case OverviewBritCitsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Natural Is at Ion As A British Citizen MGHOCDokument17 SeitenNatural Is at Ion As A British Citizen MGHOCAsad Ali KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SWF Legal Report 2013 I.sbloccatoDokument75 SeitenSWF Legal Report 2013 I.sbloccatoGB LiotineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax Guide On The Deduction of Medical, Physical Impairment and Disability Expenses (Issue 3)Dokument28 SeitenTax Guide On The Deduction of Medical, Physical Impairment and Disability Expenses (Issue 3)iadhiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Only B.II) - FinalDokument6 SeitenIE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Only B.II) - Finaltunca_olcaytoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Payroll in The Netherlands - Things You Must KnowDokument3 SeitenPayroll in The Netherlands - Things You Must KnowJohn Ricky AsuncionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Double Taxation - Methods of Avoiding It at National and International LevelDokument6 SeitenDouble Taxation - Methods of Avoiding It at National and International LevelIgor BanovićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Universal Credit and The Severe Disability PremiumDokument9 SeitenUniversal Credit and The Severe Disability Premiumbob leaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1936 (CTH) Does Not Define The Term Resides', Therefore Its Ordinary Meaning FromDokument8 Seiten1936 (CTH) Does Not Define The Term Resides', Therefore Its Ordinary Meaning FromDessiree ChenNoch keine Bewertungen

- EE - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Only B.II) - FinalDokument5 SeitenEE - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Only B.II) - Finaltunca_olcaytoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect V1 2 Summer2007DubeRossiSurmatzDokument2 SeitenEffect V1 2 Summer2007DubeRossiSurmatzNyegosh DubeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflections On 6 Years of Public PolicyDokument5 SeitenReflections On 6 Years of Public PolicyrmdantonNoch keine Bewertungen

- INSIGHT Spring Singles LoDokument6 SeitenINSIGHT Spring Singles LoPeng WangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2. EditedDokument9 SeitenChapter 2. EditedJellah Lorezo AbreganaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budget 2013Dokument0 SeitenBudget 2013Ern_DabsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Sector Accounting StandardsDokument41 SeitenPublic Sector Accounting StandardsIlham Wahyudi Lubis100% (2)

- Accepting Volunteers From Overseas: Volunteering England Information Sheet © Volunteering England 2008Dokument7 SeitenAccepting Volunteers From Overseas: Volunteering England Information Sheet © Volunteering England 2008ImprovingSupportNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judgment Given OnDokument40 SeitenJudgment Given OnLegal CheekNoch keine Bewertungen

- p035-062 U3 Topic 2Dokument28 Seitenp035-062 U3 Topic 2ParisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joint Tax Hearing-Ron DeutschDokument18 SeitenJoint Tax Hearing-Ron DeutschZacharyEJWilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- B& CI Article Part 1Dokument3 SeitenB& CI Article Part 1vansteeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Long Residence v13.0 EXTDokument54 SeitenLong Residence v13.0 EXTInaya GeorgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Welfare Reform Timetable: Hbnotes April 2011Dokument16 SeitenWelfare Reform Timetable: Hbnotes April 2011ecx537cNoch keine Bewertungen

- MM & Ors Vs SSHD Court of Appeal JudgmentDokument74 SeitenMM & Ors Vs SSHD Court of Appeal JudgmentBritCitsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Finance Study GUIDE 2019/2020: Morning/Evening/WeekendDokument67 SeitenPublic Finance Study GUIDE 2019/2020: Morning/Evening/Weekendhayenje rebeccaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) : State Aid: Just Transition Fund (JTF)Dokument15 SeitenFrequently Asked Questions (FAQ) : State Aid: Just Transition Fund (JTF)amicoadrianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Horner Downey 2011 Budget BookletDokument17 SeitenHorner Downey 2011 Budget BookletgsdltdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Movement FinanceDokument44 SeitenMovement FinancemalatebusNoch keine Bewertungen

- CCS207 CCS1020373376-002 Explanatory Memorandum To HC 813 Web AccessibleDokument50 SeitenCCS207 CCS1020373376-002 Explanatory Memorandum To HC 813 Web AccessibleshadowyyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Public Money AA v2 - Chapters Annex WebDokument212 SeitenManaging Public Money AA v2 - Chapters Annex WebM Javaid Arif Qureshi100% (1)

- The TRAIN Law and The Poor Antonio P. Contreras: BY ON JANUARY 30, 201Dokument7 SeitenThe TRAIN Law and The Poor Antonio P. Contreras: BY ON JANUARY 30, 201Jellah Lorezo AbreganaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DWP Update March 2020.204461260Dokument7 SeitenDWP Update March 2020.204461260Sanjeev SaharanNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) Directive Amendments On Foreign Exchange (2016/2017)Dokument3 SeitenNational Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) Directive Amendments On Foreign Exchange (2016/2017)simbiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Codul Fiscal (In Limba Engleza)Dokument65 SeitenCodul Fiscal (In Limba Engleza)Cristina CiobanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contributory BenefitsDokument13 SeitenContributory BenefitsGail WardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 109 / Wednesday, June 6, 2012 / NoticesDokument25 SeitenFederal Register / Vol. 77, No. 109 / Wednesday, June 6, 2012 / NoticesMarketsWikiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malta in A NutshellDokument4 SeitenMalta in A NutshellsjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- RFUK Living Online and Covid Impact Report - SGDokument35 SeitenRFUK Living Online and Covid Impact Report - SGsjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surinder Singh For Newbies Extended Edition IRELAND 2015Dokument9 SeitenSurinder Singh For Newbies Extended Edition IRELAND 2015sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ilmfs Faq 2020Dokument56 SeitenIlmfs Faq 2020sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surinder Singh For Newbies Extended 2014Dokument9 SeitenSurinder Singh For Newbies Extended 2014sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ilmfs Faq 2020Dokument57 SeitenIlmfs Faq 2020sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Living and Working in The NetherlandsDokument28 SeitenLiving and Working in The NetherlandssjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mailer Jun2014Dokument3 SeitenMailer Jun2014sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surinder Singh in The Netherlands by Amanda Briggs-HastieDokument6 SeitenSurinder Singh in The Netherlands by Amanda Briggs-HastiesjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stats From BC PollDokument2 SeitenStats From BC PollsjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonel Witness Statement - 16 PagesDokument16 SeitenSonel Witness Statement - 16 PagessjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sslpa Imm April 2003Dokument12 SeitenSslpa Imm April 2003sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- FAQDokument13 SeitenFAQsjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Right of Union Citizens and Their Family Members ToDokument23 SeitenRight of Union Citizens and Their Family Members Toapi-25886097Noch keine Bewertungen

- New Surinder Singh Rules 11dec2013Dokument8 SeitenNew Surinder Singh Rules 11dec2013sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stats From BC PollDokument2 SeitenStats From BC PollsjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Date of Submission: 28 March 2014 Submitted By: Sonel Mehta: ConcernsDokument4 SeitenDate of Submission: 28 March 2014 Submitted By: Sonel Mehta: ConcernssjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surinder Singh For Newbies 2014Dokument6 SeitenSurinder Singh For Newbies 2014sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- No Visa But Still Want To Travel - Freedom of Movement in The EUDokument13 SeitenNo Visa But Still Want To Travel - Freedom of Movement in The EUsjplep100% (1)

- Ss Centre of Life RulesDokument11 SeitenSs Centre of Life RulessjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

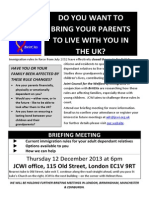

- Do You Want To Bring Your: Thursday 12 December 2013 at 6pmDokument1 SeiteDo You Want To Bring Your: Thursday 12 December 2013 at 6pmsjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADR Flyer Final-1Dokument1 SeiteADR Flyer Final-1sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- EEA2 Sections To Be Completed by Surinder SinghersDokument1 SeiteEEA2 Sections To Be Completed by Surinder SingherssjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concise Explanation of The Eu DirectiveDokument3 SeitenConcise Explanation of The Eu DirectivesjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dmser Vol2 36Dokument3 SeitenDmser Vol2 36sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nate 3759328Dokument3 SeitenNate 3759328sjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dees Nightmare TripDokument6 SeitenDees Nightmare TripsjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dissertation AnaMacouzet edOCT PDFDokument61 SeitenDissertation AnaMacouzet edOCT PDFsjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dissertation AnaMacouzet edOCTDokument50 SeitenDissertation AnaMacouzet edOCTsjplepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Accounting: A Business Partner: Lecture # 1Dokument15 SeitenManagement Accounting: A Business Partner: Lecture # 1Amna NasserNoch keine Bewertungen

- FORM Presentation Nov 13thDokument10 SeitenFORM Presentation Nov 13thMohamad WafiyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Accounting Standard 25 Association of Indonesian AccountantsDokument15 SeitenFinancial Accounting Standard 25 Association of Indonesian Accountantsapi-3708783100% (1)

- Bob Livingston: ManagementDokument3 SeitenBob Livingston: Managementapi-103906346Noch keine Bewertungen

- A. Present Value PMT/iDokument2 SeitenA. Present Value PMT/iABDUL WAHABNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 9 Multiple ChoicesDokument5 SeitenChapter 9 Multiple Choicesshiroe raabuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurial Finance - Cachet CaseDokument5 SeitenEntrepreneurial Finance - Cachet CaseRoderick0% (1)

- Po 001 Iciecpl Ankit Const. 3Dokument9 SeitenPo 001 Iciecpl Ankit Const. 3Anjani KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application: The Costs of Taxation: Marwa HeggyDokument42 SeitenApplication: The Costs of Taxation: Marwa HeggyAnonymous cioChTZoVNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Compliance Check ListDokument1 SeiteStatutory Compliance Check Listr.logesh p.rajendrenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Report at KelDokument76 SeitenProject Report at KelAsif HashimNoch keine Bewertungen

- SFDM Individual Assignment (LMH)Dokument8 SeitenSFDM Individual Assignment (LMH)Fuhgandu RashydNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dupont AnalysisDokument4 SeitenDupont Analysisangelavani_16Noch keine Bewertungen

- Financial MarkatingDokument22 SeitenFinancial Markatingvishu shindeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Far1 Artt Ias 8 & 33 Test QPDokument1 SeiteFar1 Artt Ias 8 & 33 Test QPHassan TanveerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 00 Tapovan Advanced Accounting Free Fasttrack Batch BenchmarkDokument144 Seiten00 Tapovan Advanced Accounting Free Fasttrack Batch BenchmarkDhiraj JaiswalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accountancy GoodwillDokument5 SeitenAccountancy GoodwillPrachi SanklechaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice For Midterm 1Dokument136 SeitenPractice For Midterm 1ennaira 06Noch keine Bewertungen

- St. Vincent College of Cabuyao: Brgy. Mamatid, City of Cabuyao, Laguna Advance Financial Accounting and ReportingDokument3 SeitenSt. Vincent College of Cabuyao: Brgy. Mamatid, City of Cabuyao, Laguna Advance Financial Accounting and ReportingGennelyn Grace Peñaredondo100% (1)

- NCND ImfpaDokument10 SeitenNCND Imfpadoug dam100% (1)

- Tybcom Question BankDokument21 SeitenTybcom Question BankPraful KhatateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leasco Corporation, Plaintiff-Respondent v. Peter T. Taussig, 473 F.2d 777, 2d Cir. (1972)Dokument13 SeitenLeasco Corporation, Plaintiff-Respondent v. Peter T. Taussig, 473 F.2d 777, 2d Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project For Course of Manufacturing Resource Planning: Industry Sector - FMCGDokument12 SeitenProject For Course of Manufacturing Resource Planning: Industry Sector - FMCGalhad1986Noch keine Bewertungen

- Construction Equipment Management BookDokument130 SeitenConstruction Equipment Management BookJosse Shandra100% (9)

- Capital Budgeting Idea For Netflix Inc.Dokument26 SeitenCapital Budgeting Idea For Netflix Inc.PraNoch keine Bewertungen

- November 13, 2020 Strathmore TimesDokument16 SeitenNovember 13, 2020 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 11Dokument4 SeitenChapter 11محمد الجمريNoch keine Bewertungen