Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Slaying Goliath - Martin Capital Management Q2

Hochgeladen von

CanadianValueCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Slaying Goliath - Martin Capital Management Q2

Hochgeladen von

CanadianValueCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Slaying Goliath

Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan delivered a rather dry and complex speech on December

5, 1996. The reaction, however, to such a seemingly mundane oration was unexpectedly immediate

and powerful. It rattled Greenspans confidence. He had innocuously uttered the now infamous

phrase irrational exuberance, and the mighty market roared its disapproval.

For several days, Bloomberg screens turned an angry red around the world. The Maestro was no

David when he came face to face with Goliath. Greenspan cowered in the giants presence, fear

blinding him to the ogres fragilities. Sadly, it was an opportunity lost because it is in the crucible of

confronting giantswith everything on the linethat true grit makes the most difference in what

the future will hold.

Many of us have had to square off with Goliaths in our own lives.

The fact that youre still reading

and Im still writing is probably all that needs to be said.

Tragically for the victims of misguided policies, it would appear that appointed Federal Reserve

Board chairpersons, with no skin in the monetary policy game, are exempt from the consequences

of their own actions.

As speculation became more pervasive and the bubble expanded, Greenspan stood by passively,

neither raising interest rates nor imposing the more subtle so-called macroprudential financial

regulatory and oversight weapons in the Feds arsenal. Instead, he dosed the bipolar Goliath with

easy money whenever an intense mood swing threatened the markets upward trajectory, a crowd-

reassuring maneuver he had first executed after the crash of 1987.

The easy-money elixir was administered again in 1998 after the Russian debt crisis and the collapse

of Long-Term Capital Management, and then two years later on the eve of the millennium when the

Fed was spooked by Y2K. By the dot-com bust in the early 2000s, Greenspans deep-seated

apprehensions about the economic aftershocks of a potentially significant market decline were well

known and programmed into investors expectations. Emboldened, they began to refer to the

seemingly autonomic response as the Greenspan put. He used the tactic again on January 3, 2001,

even though evidence of impending recession was vague at best. The NASDAQ applauded, rising

14% on the news, its single biggest one-day advance ever. Lest we forget, central bankers are

human, and (like most of us) they yearn for approbation. Money, a tangible and eminently fungible

surrogate, tends to flood in over the transom only after they leave office.

Less than two years later, on October 15, 2002, Princeton professor Ben Bernanke gave his first

speech just two months after being appointed by President George W. Bush to Greenspans Federal

Reserve Board. Bernankes lecture came in the midst of the dot-com bust that his mentor, the

chairman, had some hand in fomenting. Perplexingly, given Bernankes nonexistent frontline

experience, the topic was: Asset-Price Bubbles and Monetary Policy.

1

1

Bernanke, Benjamin S. October 15, 2002, remarks before the New York Chapter of the National Association for

Business Economics. New York, NY.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/Boarddocs/Speeches/2002/20021015/default.htm

Obfuscating the difficulty of the Fed pinpointing, let alone pricking, bubbles, faithful understudy

Bernanke cited the earlier work of Yale financial economist Bob Shiller, who had testified at the Fed

on December 3, 1996.

2

The presentation was published in 1998 by the Journal of Portfolio

Management.

3

Shiller, Bernanke observed with the air of dj vu that only hindsight affords, was

among those warning of a bubble in stock prices. The Fed rookie staked his claim as a card-carrying

member of the board with a simple quantitative point. Referencing the Journal article, Bernanke

noted Shiller had argued that at 750 on the broad-based S&P 500 index, the market was trading at

three times its fundamental value.

Shiller used a rudimentary but reliable dividend/price regression

model.

4

The S&P continued to rise, peaking at double that number three years later.

Future Fed Chairman Bernanke declared:

I do not know, of course, where the stock market will go tomorrow, much less in the longer run (thats

really my whole point) [emphasis added]. But I suspect that Shillers implicit estimate of

the long-run value of the market was too pessimistic and that, in any case, an attempt

to use this assessment to make monetary policy in early 1997 (presumably, a severe

tightening would have been called for) might have done much more harm than good.

5

Bernankes assertion is absurd on its face. The surreal and revealing first point seems more suitable

to weather forecasting where long-term forecasts are much more difficult than short-term ones, the

antithesis of the way any rational investor thinks about equity market dynamics over the dimension

of time. If we didnt have confidence that stocks would generally rise in the long run, why in the

world would anyone invest a dime? The last point, a counterfactual assumption about the effect of

tightening, was never tested by Bernanke. The signature policy of his eight-year tenure as Fed

chairman was its polar opposite: unprecedented and unrestrained massive monetary easing.

We all know that Ben Bernanke opted out on the cusp of what just might be a very messy

unwinding of the extraordinary near six-year-and-counting shower of Fed largesse when he retired

6

as Fed chairman in early 2014. Did he hear Goliaths thundering footsteps over the hill? But what

about Bob Shiller after his errantly premature forecast? Beginning in 1997, did he slink into the

shadows like Greenspan, humbled by the almighty market? You be the judge. If one studies

Shillers 1998 research (see footnote 3), it appears scholarly, courageous, without an economists

equivocation, and above all, rational in an era marked by extreme irrationality.

2

Curiously, Shiller testified two days before Greenspans irrational exuberance speech. Could it be that Greenspan

was influenced by Shillers analysis? Its also worth noting that Greenspans choice of words later became the title of

Shillers compelling book Irrational Exuberance.

3

Shiller, Robert, & Campbell, John. Valuation Ratios and the Long-Run Stock Market Outlook, The Journal of Portfolio

Management, Winter 1998. http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/online/jpmalt.pdf

4

Shillers linear regressions of price changes in total returns on the valuation ratios suggested substantial declines in real

stock prices, and real stock returns close to zero, over the next 10 years. The S&P 500 fell below 750 in the spring of

2009, twelve years later.

5

Bernanke, op. cit.

6

Bernankes predecessor, Greenspan, served 19 years as Fed chairman. Bernanke served eight years in the same

position.

Confronting the beast with everything on the line, Shiller went on to write the audaciously titled book

Irrational Exuberance, which was published at the very peak of the market in early 2000. In yet another

example of originality and verve, in 2005 he came back with a second edition, this one little changed

from the first except for a new section highlighting the rampant speculation in real estate. Its obvious

that Bob Shiller took a chapter out of Benjamin Grahams playbook:

If you have formed a conclusion from the facts and if you know your judgment is

sound, act on iteven though others may hesitate or differ. You are neither right nor

wrong because the crowd agrees with you. You are right because your data and

reasoning are right.

7

Shiller was and is a David, as confirmed last winter by his take-no-prisoners Nobel Prize lecture and

subsequent papers.

Shillers objective was to be generally right, and at all costs to avoid being precisely wrong. As the

Journal article makes clear, Shillers standard was not the impossible exactitude of a point forecast.

Recognizing a potential problem is a skill possessing intrinsic worth, for such problems are

knowable only if one studies and understands the imprecise but ultimately undeniable

connection between price and valuenot the timing of its unraveling, which of course is

unknowable with the same degree of accuracy. Shillers added value in recognizing the potential

problem was not negated by his inability to pinpoint precisely when it would come to a head.

Bernankes prognostications from his very first day as chairman revealed no such concessions to

immutable realities.

Moving to the present, Janet Yellen, in a speech at the IMF as recently as July 2, made it clear that

she embraces the party line: Monetary policy should not be used against incipient bubbles.

In my remarks, I will argue that monetary policy faces significant limitations as a tool

to promote financial stability: Its effects on financial vulnerabilities, such as excessive

leverage and maturity transformation, are not well understood and are less direct than

a regulatory or supervisory approach; in addition, efforts to promote financial stability

through adjustments in interest rates would increase the volatility of inflation and

employment. As a result, I believe a macroprudential approach to supervision and

regulation needs to play the primary role.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, I do not presently see a need for

monetary policy to deviate from a primary focus on attaining price stability and

maximum employment, in order to address financial stability concerns. That said, I

do see pockets of increased risk-taking across the financial system, and an acceleration

or broadening of these concerns could necessitate a more robust macroprudential

approach. For example, corporate bond spreads, as well as indicators of expected

volatility in some asset markets, have fallen to low levels, suggesting that some

investors may underappreciate the potential for losses and volatility going forward. In

addition, terms and conditions in the leveraged-loan market, which provides credit to

7

Graham, Benjamin, The Intelligent Investor, 4

th

edition (1973), Chapter 20, p. 287.

lower-rated companies, have eased significantly, reportedly as a result of a reach for

yield in the face of persistently low interest rates.

8

Before bashing Ms. Yellen, we must respectfully acknowledge that shes the third runner in the Feds

easy-money, three-leg relay. She was passed the baton by Ben Bernanke, who took it from lead-off

runner Alan Greenspan. The race is on: It is most unlikely that she will raise rates until she crosses

the finish line, wherever she opts to draw it on the track. The reality is that no Fed chairman since

Paul Volcker has had the courage of a David to lean against the wind with the full force of the Feds

power. Volckers Goliath was the clear and present danger of double-digit inflation. Yellens is a

more subtle but perhaps no less insidious inflation in financial asset prices. In the end, it could be

that Paul Volcker may have faced a less daunting enemy.

Even though a preemptive raising of rates is out of the question, Yellen is not powerless. In

advocating a robust macroprudential approach, which, for lay readers, means almost anything in

the Feds toolbox excluding raising rates, I believe raising stock margin requirements could send a

conspicuous warning to retail investors about increased risk-taking and reach[ing] for yield in

the face of persistently low interest rates, the demon of the Feds own design. Investors may not

heed the Feds admonition, but to do nothing constitutes willful negligence. Although margin

requirements were frequently used as a tool after being authorized in 1934, the Fed has left them

unchanged at 50% since 1974, in part because Greenspan repeatedly argued that such a move would

be ineffective (see quote box below).

For the counterpoint and so much more, see the concise op-ed piece Bob Shiller wrote for the Wall

Street Journal on August 10, 2000 posted immediately following this commentary. For those who did

8

Yellen, Janet. Monetary Policy and Financial Stability. July 2, 2014 speech at the 2014 Michel Camdessus Central

Banking Lecture, International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C.

Alan Greenspan on the Impact of Margin Requirements (A Small Sample)

There is no evidence to suggest margin requirements have an effect on the level of stock

prices.

Alan Greenspan, remarks to the Economic Club of New York, January 14, 2000

Senator, as you comment quite correctly, the reason over the years that we have been

reluctant to use the margin authority which we currently have is that all of the studies have

suggested that the level of stock prices have nothing to do with margin requirements. That is,

there is no evidence to suggest that changes in margin requirements up or down in years prior

to 1974, when we did move them back and [forth], had any effect on prices.

Alan Greenspan, confirmation hearing, Senate Banking Committee, January 26, 2000

The problem that I have had with the issue of moving our margins is not a concern of what it

would do to the marketplace, its the evidence which suggests that it has very little impact on

the price structure on the market or anything else.

Alan Greenspan, Humphrey-Hawkins hearing, House Banking Committee, February 17, 2000

not fare well when the euphoric dot-com mania came to its inevitable screeching halt, imagine how

different things would have been if they had picked up the Journal that day, read Shillers short op-ed

piece, and acted decisively upon it. Thats yesterday. Shillers remarkably prescient and succinct

essay is attached because I believe it is as relevant today as it was 14 years ago.

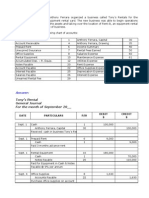

The accompanying graph, meanwhile, is included for effect. Many others could have been used, but

few are as easy to grasp at a glance. Although there is a quickly discernible correlation between

movements in the S&P 500 and NYSE margin account debit balances, correlation is not

causationi.e., expanding (or contracting)

margin balances are merely coincidental,

and not leading, indicators. Like the

Shiller PE to which I often refer, the

relative level of margin debt offers some

indication about whether investors in

general are in a risk-embracing or a risk-

avoiding frame of mind. When they are

aggressively, and most often unwittingly,

following the crowd in chasing risky

investments, the end, whenever it occurs,

is not good. As noted above, we believe

that recognizing a potential (and

knowable) problem is a skill worth paying

for (in option premiums and management

fees), not the timing of its unraveling,

which is far less knowable.

Prem Watsa, the iconoclastic CEO of the Toronto-based Fairfax Financial, a $35 billion insurance

company, understands both the importance of identifying the problem and the pain of preparing for

it well in advance of others. He offered the following candid insights in his 2013 letter to

shareholders:

In this environment, with zero interest rates and high debt levels prevailing in most

developed countries, giving them limited flexibility to react to unintended

consequences, we think it is prudent to have a very strong balance sheet with a large

cash position and to be protected on the downside. When problems hit, only those

with cash and very liquid assets can take advantage of them. While it is very painful

and costly waiting, we think your (and our!) patience will be rewarded. We are

reminded again of the warning from the distant past from our mentor, Ben Graham,

which I have quoted before: Only 1 in 100 survived the 19291932 debacle if one

was not bearish in 1925. We continue to be earlyand bearish!

Watsa is a David. His equity portfolio is 100% hedged with equity index swaps, and he also has a

huge economic derivatives hedge that anticipates deflation will appear before inflation has its day.

He argues that deflation would wreak havoc on most of his businesses. Since taking his stand in

2010, the book value of Fairfax has withered from $376 per share to $339 in the rising market, with

the cost of hedges more than offsetting solid returns in his operating businesses. Lest Watsa be

thought a Cassandra, Fairfaxs book value was $150 in 2006 when he positioned the companys

portfolio to benefit from tail risks that he saw as a problemeven though he had no idea when they

might occur. When you tally things up, including those years when Fairfax badly lagged behind the

indices, the companys book value has compounded at 21.3% since its founding in 1985. Seth

Klarman (Baupost Group), about whom Ive written extensively, has a similarly successful

contrarian streak.

Like Bob Shiller, Prem Watsa, and Seth Klarman, we believe we know how to do battle with our

Goliath. The key is to not do it on his terms. As emphasized in our 2013 annual report, we will

surely lose if we fight conventionally. We must be cunning and creative in our decisions and actions.

Off the field we must be open to suffering the ridicule of the majority; we must even be willing to

look stupid. The story of David and Goliath is embedded in our language as a metaphor for

improbable victory, which Malcolm Gladwell eloquently argues is a near universal misunderstanding

of the biblical showdown. As one discovers in reading the latest of Gladwells improbable books,

9

Davids tactics and strategy actually stacked the odds decidedly against Goliath. Davids victory was

anything but improbable. Breaking convention, using speed and surprise, brandishing the sling and

not the sword, David triumphed over the myth of power being solely a function of physical might

or, in our field battle, the manic/depressive brute of a market that by dint of size and anonymity

intimidates so manyeven The Maestro.

Our victory becomes much more probable if we first avoid loss by turning a deaf ear to the siren

song of the amorphous crowd of which the market is a manifestation, and then figuratively using the

leverage of the sling rather than the limited edge of the sword to seize the advantage. Ultimately,

though, we simply want to have lots of liquidity when others are willing to pay a fortune in lost

opportunity to take it off our hands.

One final observation: Notice that Ben Graham said (see Prem Watsas blocked quote above) an

investor had to be bearish in 1925 to avoid the 192932 debacle. You may ask yourself, Was that

a misprint? Didnt he mean 1928 or early 1929? Why so early? Investors would have missed three

full years of strong returns, wouldnt they? Well, there are very good answers to those insightful

questions and like the keep-you-coming-back tactics of House of Cards on Netflix, well share

our research and insightsincluding a plausible response to your rhetorical inquiriesin the 2014

third-quarter QCM Review.

Frank K. Martin, CFA

July 2014

frank@mcmadvisors.com

9

Gladwell, Malcolm (2013-10-01). David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants. Little, Brown and

Company.

Margin Calls: Should the Fed Step In?

Yes, It may Avert Disaster

By Robert Shiller August 10, 2000

The stock market is in its most dramatic boom ever. Despite last week's declines in tech stocks, the

Standard & Poor's composite price-earnings ratio (real prices divided by the 120-month average of

trailing real earnings) stands at 46. Until the present boom, the highest it had ever been (the data go

back to 1871) was 33, in September 1929 -- the month before the crash. The dividend yield on the

Standard & Poor's index stands at 1.1%, the lowest ever. The previous low was 2.6% in January

1973, just before the 1973-74 crash. Margin debt is soaring; it has increased 87% in the past year.

In the midst of this record-breaking boom, the Federal Reserve Board remains silent about the

speculative level of the market, neither commenting that the market is too high nor using its powers

over margin requirements to dampen the markets. This inaction is unfortunate. Distortions of

saving and investing behavior, driven by the public's illusion of stock-market wealth, are rampant,

and the risks of economic dislocations and massive wealth redistribution are very serious if the

market continues to soar and then crashes.

There are, of course, some who assert that the market is rationally high because of new technology

that makes the outlook for future corporate profits very bright. But people have hailed "new eras"

before -- in 1901, they cited the formation of giant corporations that would supposedly produce

economics of scale; in 1929, it was electrification, chain stores and the spread of automobiles; in

1973, advancing productivity and technology. All of these "new eras" turned out not to be so

revolutionary after all, and odds are today's market won't be any different.

The Fed used to change its margin requirements actively as a tool against speculative movements in

the stock market, raising the requirement when the market got too hot and lowering it when things

cooled. Between 1934 and 1974, the Fed changed this margin requirement 22 times, often with

explicit statements that its aim was to restrain "speculation" in the stock market. But for 26 years the

Fed has kept the margin requirement constant, at 50%.

The best policy for the Fed lies somewhere between these two extremes-between the hyperactive

pre-1974 policy and the static policy since. The Fed should probably not attempt to fine-tune the

level of the market as it once did. But it should occasionally make adjustments in margin

requirements in times of major market misalignments, such as the speculative situation we see in the

market today.

Why did the Fed abruptly abandon its active margin-requirement policy in 1974? An important

factor was the influence of efficient-markets theory, the idea that markets always work extremely

well. Eugene Fama's highly influential academic article "Efficient Capital Markets" appeared in 1970,

and Burton Malkiel's efficient-markets book, "A Random Walk Down Wall Street," was first

published in 1973. Ever since, the efficient markets theory has been a powerful influence. Most of

our leaders who might feel like commenting on the level of the market have retreated from doing so,

thinking such an action might be viewed as rash and irresponsible.

The efficient markets theory, unfortunately, is only a half-truth. The theory is right in the sense that

it is indeed extremely hard to predict changes in the market over the next few months or a year. But

the theory is wrong when it asserts that it is impossible for careful observers to detect that the

market is a historic speculative bubble, as it has been in recent years.

Another factor making the policy of changing margin requirements look less attractive after 1974

was the rapid increase in sophistication of our financial markets since around that time, which

created many new opportunities other than margin credit for investors to leverage their investments.

Notably, the Chicago Board Options Exchange opened trading in stock options in 1973. Now

individual investors can easily take speculative options positions in stocks without using margin

credit. Yet this does not mean that the Fed should not take the limited action that raising margin

requirements represents, for such an action will still be an important signal to the markets.

When the Fed actively managed margin requirements before 1974, it was following a fairly

consistent policy of attempting to restrain speculation. Each of the 12 times margin requirements

became more restrictive, stock prices had increased over the prior six months, often dramatically. In

nine of the 10 times margin requirements were relaxed, stock prices had declined over the prior six

months. Thus, it appears that the Fed was attempting to lean against prior stock market price

changes. Moreover, there was some tendency for the Fed to keep margin requirements relatively

high in times when the market price/earnings ratio was high, and relatively low when the P/E ratio

was low.

At Times Erratic

Though the Fed's changes in the requirements were invariably controversial, and at times erratic, on

balance the policy probably made some sense. If the Fed were to follow the same procedures today,

given both very high price/earnings ratios and recent price increases, margin requirements would

probably be over 90% now. The absence of such a reaction from the Fed board members today, the

abandonment of their old concern about speculation, and the reluctance of national leaders to say

anything about speculation in the market, must be part of the reason why the current boom is bigger

than any before.

While the Fed should be very wary on principle of intervening in markets, increasing the margin

requirement today would stand as a warning to investors not to leverage themselves up excessively

and would work in the direction of cooling the market. Increasing margin requirements a little, to

60% say, and grand fathering existing margin credit so as not to induce an immediate crisis, would

send a healthy caution signal. It is the most important step the Fed can take at this time of historic

misvaluation in the stock market.

Mr. Shiller is a professor of economics at Yales International Center for Finance and author of "Irrational

Exuberance" (Princeton University Press, 2000)

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Greenlight UnlockedDokument7 SeitenGreenlight UnlockedZerohedgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- 'Long Term or Confidential (KIG Special) 2015Dokument12 Seiten'Long Term or Confidential (KIG Special) 2015CanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Stan Druckenmiller Sohn TranscriptDokument8 SeitenStan Druckenmiller Sohn Transcriptmarketfolly.com100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Stan Druckenmiller The Endgame SohnDokument10 SeitenStan Druckenmiller The Endgame SohnCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- OakTree Real EstateDokument13 SeitenOakTree Real EstateCanadianValue100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- 2015 q4 Crescent Webcast For Website With WatermarkDokument38 Seiten2015 q4 Crescent Webcast For Website With WatermarkCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Stock Market As Monetary Policy Junkie Quantifying The Fed's Impact On The S P 500Dokument6 SeitenThe Stock Market As Monetary Policy Junkie Quantifying The Fed's Impact On The S P 500dpbasicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Charlie Munger 2016 Daily Journal Annual Meeting Transcript 2 10 16 PDFDokument18 SeitenCharlie Munger 2016 Daily Journal Annual Meeting Transcript 2 10 16 PDFaakashshah85Noch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- KaseFundannualletter 2015Dokument20 SeitenKaseFundannualletter 2015CanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fpa Crescent FundDokument51 SeitenFpa Crescent FundCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Fairholme 2016 Investor Call TranscriptDokument20 SeitenFairholme 2016 Investor Call TranscriptCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Market Macro Myths Debts Deficits and DelusionsDokument13 SeitenMarket Macro Myths Debts Deficits and DelusionsCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Tilson March 2016 Berkshire ValuationDokument26 SeitenTilson March 2016 Berkshire ValuationCanadianValue100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hussman Funds Semi-Annual ReportDokument84 SeitenHussman Funds Semi-Annual ReportCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Munger-Daily Journal Annual Mtg-Adam Blum Notes-2!10!16Dokument12 SeitenMunger-Daily Journal Annual Mtg-Adam Blum Notes-2!10!16CanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- UDF Overview Presentation 1-28-16Dokument18 SeitenUDF Overview Presentation 1-28-16CanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Gmo Quarterly LetterDokument26 SeitenGmo Quarterly LetterCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- Weitz - 4Q2015 Analyst CornerDokument2 SeitenWeitz - 4Q2015 Analyst CornerCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2015Q3 Webcast Transcript LLDokument26 Seiten2015Q3 Webcast Transcript LLCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Einhorn Consol PresentationDokument107 SeitenEinhorn Consol PresentationCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Einhorn Q4 2015Dokument7 SeitenEinhorn Q4 2015CanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- IEP Aug 2015 - Investor Presentation FINALDokument41 SeitenIEP Aug 2015 - Investor Presentation FINALCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hayman Capital Management LP - Clovis Oncology Inc VFINAL HarvestDokument20 SeitenHayman Capital Management LP - Clovis Oncology Inc VFINAL HarvestCanadianValue100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Einhorn Consol PresentationDokument107 SeitenEinhorn Consol PresentationCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kase Q3&Oct 15 LtrsDokument21 SeitenKase Q3&Oct 15 LtrsCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whitney Tilson Favorite Long and Short IdeasDokument103 SeitenWhitney Tilson Favorite Long and Short IdeasCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steve Romick FPA Crescent Fund Q3 Investor PresentationDokument32 SeitenSteve Romick FPA Crescent Fund Q3 Investor PresentationCanadianValue100% (1)

- Investors Title InsuranceDokument55 SeitenInvestors Title InsuranceCanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fpa Crescent Fund (Fpacx)Dokument46 SeitenFpa Crescent Fund (Fpacx)CanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- PTS Morning Call 12-14-09Dokument4 SeitenPTS Morning Call 12-14-09PrismtradingschoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stock Market IndicesDokument15 SeitenStock Market IndicesSIdhu SimmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- WSJ - Li Lu ProfileDokument5 SeitenWSJ - Li Lu ProfilezemblaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joint VentureDokument2 SeitenJoint VentureAries Gonzales CaraganNoch keine Bewertungen

- IFFSSAFinal Report 2 May 22Dokument133 SeitenIFFSSAFinal Report 2 May 22Tom CochranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cup 1 FA 1 and FA 2Dokument16 SeitenCup 1 FA 1 and FA 2Thony Danielle LabradorNoch keine Bewertungen

- OFOD7 e Test Bank CH 03Dokument2 SeitenOFOD7 e Test Bank CH 03Danny NgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fipb Review 2011-13Dokument100 SeitenFipb Review 2011-13mailnevadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fsa Practical Record ProblemsDokument12 SeitenFsa Practical Record ProblemsPriyanka GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recession Normal ExpansionDokument3 SeitenRecession Normal ExpansionAshish BhallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annexure 2Dokument13 SeitenAnnexure 2Shalini SrivastavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Investors Perception Towards Real Estate InvestmentDokument38 SeitenInvestors Perception Towards Real Estate InvestmentMohd Fahd Kapadia25% (4)

- LCCI Level I (Book-Keeping) : Course OutlineDokument5 SeitenLCCI Level I (Book-Keeping) : Course OutlineGergana DraganovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 Financial Statement AnalysisDokument7 SeitenChapter 4 Financial Statement AnalysisAnnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tony's Rentals General Journal For September 20Dokument17 SeitenTony's Rentals General Journal For September 20Rehan Mehmood63% (8)

- Jawaban Buku ALK Subramanyam Bab 7Dokument8 SeitenJawaban Buku ALK Subramanyam Bab 7Must Joko100% (1)

- T1 Importance of Mutual FundsDokument2 SeitenT1 Importance of Mutual Fundsharsh agarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prob Set 1Dokument6 SeitenProb Set 1Nikki BulanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mosaic - Perspectives On Investing Download - Tìm Với GoogleDokument2 SeitenMosaic - Perspectives On Investing Download - Tìm Với GooglefdsafasfNoch keine Bewertungen

- To Analyze The Financial Performance of Axis Bank by Using RatiosDokument16 SeitenTo Analyze The Financial Performance of Axis Bank by Using RatiosPrasad S. NayakNoch keine Bewertungen

- 57-The Last-Hour Trading Technique PDFDokument4 Seiten57-The Last-Hour Trading Technique PDFNavin Chandar100% (1)

- Liquidity, Risk and Profitability AnalysisDokument13 SeitenLiquidity, Risk and Profitability AnalysisMichael Neal100% (1)

- Capital Adequacy Ratio - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokument4 SeitenCapital Adequacy Ratio - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaTrần Kim ChungNoch keine Bewertungen

- COST OF CAPITAL - Basic FinanceDokument21 SeitenCOST OF CAPITAL - Basic FinanceAqib IshtiaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acca Paper F3 Financial Accounting Mock Exam Prepared By: MR Yeo Hong AnnDokument23 SeitenAcca Paper F3 Financial Accounting Mock Exam Prepared By: MR Yeo Hong AnnRajeshwar Nagaisar50% (2)

- Profitable Short Term Trading StrategiesDokument196 SeitenProfitable Short Term Trading Strategiessupriya79% (29)

- Topic 30 Cross Reference To GARP Assigned Reading - The Institute For Financial Markets, Chapter 1Dokument1 SeiteTopic 30 Cross Reference To GARP Assigned Reading - The Institute For Financial Markets, Chapter 1Rehan GanatraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dhana - Accounting For Managers - Ass1Dokument7 SeitenDhana - Accounting For Managers - Ass1Kiran Kumar MCNoch keine Bewertungen

- BA544 Chap 008Dokument50 SeitenBA544 Chap 008Abhay AgrawalNoch keine Bewertungen

- StockholdersDokument458 SeitenStockholdersMica Joy FajardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- These Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaVon EverandThese Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (8)

- These are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaVon EverandThese are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (14)

- Joy of Agility: How to Solve Problems and Succeed SoonerVon EverandJoy of Agility: How to Solve Problems and Succeed SoonerBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Burn the Boats: Toss Plan B Overboard and Unleash Your Full PotentialVon EverandBurn the Boats: Toss Plan B Overboard and Unleash Your Full PotentialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Venture Deals, 4th Edition: Be Smarter than Your Lawyer and Venture CapitalistVon EverandVenture Deals, 4th Edition: Be Smarter than Your Lawyer and Venture CapitalistBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (73)

- Mastering Private Equity: Transformation via Venture Capital, Minority Investments and BuyoutsVon EverandMastering Private Equity: Transformation via Venture Capital, Minority Investments and BuyoutsNoch keine Bewertungen