Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Valentino Pittoni

Hochgeladen von

Jāfri Wāhid0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

59 Ansichten8 Seitenthe life of valentino pittoni the life of valentino pittoni the life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittoniv

Originaltitel

Valentino Pittoni.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenthe life of valentino pittoni the life of valentino pittoni the life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittoniv

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

59 Ansichten8 SeitenValentino Pittoni

Hochgeladen von

Jāfri Wāhidthe life of valentino pittoni the life of valentino pittoni the life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittonithe life of valentino pittoniv

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 8

Valentino Pittoni

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Valentino Pittoni

Valentino Pittoni c. 1907

Member of the Austrian Imperial Council

In office

19071918

Constituency Trieste (Old City and San Giacomo)

Personal details

Born May 23, 1872

Brazzano, Cormons

Died April 11, 1933 (aged 60)

Vienna

Political party Social Democratic Workers Party of Austria

Children

Bianca Pittoni (19041993)

Nerina Pittoni

Valentino Pittoni (German: Valentin Pittoni; May 23, 1872 April 11, 1933) was a socialist politician

from Trieste, who was mainly active in Austria-Hungary. As a follower of Austromarxism and militant

of the Social Democratic Workers Party of Austria (SDAP), he came to oppose both Italian

irredentism and Slovenian nationalism. In the early 20th century he emerged as the key leader of the

socialist movement in the Austrian Littoral region.

[1]

Pittoni represented Trieste in the Imperial

Council, where he became known as a proponent of electoral democracy, and was additionally a

member of Trieste's Municipal Council. He set up a cooperative movement, as one of several

ventures ensuring inter-ethnic solidarity in the Littoral.

Increasingly isolated after World War I, Pittoni was uncompromising in demanding Trieste's

autonomy within Austria, and eventually its independence from the Kingdom of Italy. He was a noted

adversary of Italian fascism, who lived his later life in exile in Vienna. His final contributions were as

a newspaper editor and doctrinaire of interwar Austrian socialism.

Contents

[hide]

1 Early life

2 Parliamentarian

3 World War

4 Exile

5 Notes

6 References

Early life[edit]

Pittoni was born on May 23, 1872, in Brazzano, part of the Cormons municipality. His father was a

textile trader. During his childhood the family moved to Trieste.

[2]

He studied at the Trade Academy

(Accademia di Commercio e Nautica) in Trieste,

[1]

and worked on his father's business.

[2]

During his

youth, Pittoni sympathized with irredentism.

[1]

He was called for military service in the Austro-

Hungarian Army, and was discharged with the rank of Second Lieutenant.

[2]

Later, Pittoni joined the Trieste Workers Society, which, despite the name, was a moderate

nationalist group with only some socialist members.

[3]

In 1896 he befriended the Austrian socialist

leader Victor Adler, who invited him to join SDAP that same year.

[4]

For the next twenty years,

Pittoni was strongly influenced by Adler's Austromarxist ideological line.

[1][5]

He lobbied for the

transformation of the Austro-Hungarian empire into a Danubian Confederation of non-territorial

nationalities.

[1][6]

A staunch internationalist, he opposed any Italian irredentist moves.

[7][8][9]

For

Pittoni, irredentism was promoted by Italian capitalists to weaken unity of the working

class.

[10]

Nonetheless, he and his movement had only marginal contacts with

the Slovene neighbours, as Pittoni resented Slovenian nationalism and opposed the Slavic claims

over Trieste (or "urban Slavism").

[11]

Pittoni joined the Social Democratic League, a Triestine branch of the SDAP, and, by 1902, was

involved in mediating between the socialists and organised labour. That year, he helped the senior

socialist leader Carlo Ucekar in directing the sterreichischer Lloyd stokers strike, but lost control of

it to anarchist agitators.

[12]

The strike ended in bloodshed. The authorities were lenient toward the

socialists, and willing to blame the strike on anarchists, but made a point of warning Pittoni to comply

in the future.

[13]

Later that year, Ucekar died; Pittoni vied for and won the post as leader of the Social Democratic

League.

[4][14][15]

With Pittoni at the helm, the Triestine socialists closer to the Austromarxist

centre,

[4][14][16]

holding the 1905 anti-war and anti-irredentist demonstration which coincided with the

official launch of SMS Erzherzog Ferdinand Max.

[9]

Parliamentarian[edit]

The 1907 Austrian general election was the first to be held with universal male suffrage. Pittoni was

elected to the Imperial Council with an absolute majority, representing the first constituency of

Trieste (covering the old city and the suburb of San Giacomo).

[17][18]

Although this was a major

victory for his version of socialism, Pittoni noted that his League lacked cadres, and reached out to

members of Italian Socialist Party (PSI), in the Kingdom of Italy, proposing that they should relocate

their militancy to Trieste.

[19]

He allowed a measure of nationalism to seep into his discourse, noting:

"It is up to us to also deal with the national issue."

[20]

In August, he represented his party at

the Stuttgart Congress of the Second International.

[19]

Like other SDAP deputies, Pittoni demanded the introduction of universal suffrage

in Transleithania, which was administered by the Gyula Andrssy government in Budapest. As he

noted in a parliamentary address of October 10, 1908: "it can no longer be indifferent to the nations

of Austria if the disenfranchised peoples and classes of Hungary still fail to receive the rights we owe

them."

[21]

Together with Adler, Etbin Kristan, Engelbert Pernerstorfer and Josef Steiner, he presided

over an SDAP Conference which demanded "freedom in Hungary".

[22]

From 1907 onwards Cesare Battisti, a left-wing intellectual inside the party from Trentino, emerged

as prominent leader of Trieste's League. Battisti and Pittoni clashed on political issues, especially

following the 1908 Bosnian crisis.

[10][15]

The latter incident had created a dissonance between the

goals of socialist internationalism and those of Austrian nationalism,

[23]

but Pittoni played it down,

arguing that many Bosniaks were already subjects of the Austrian monarchy, in Croatia-

Slavonia.

[24]

He also noted that, contrary to the indignation in Italy, Italians had nothing to

fear.

[25]

Against Pittoni, Battisti maintained an anti-militarist and separatist position.

[10][15]

Pittoni also

found himself criticised by Claudio Treves, Leonida Bissolati

[25]

and Gaetano Salvemini,

[26]

irredentist

politicians of the PSI.

Pittoni was elected municipal councillor of Trieste in 1909,

[27]

and promoted labour

management initiatives. Chief editor of the party organ, Il Lavoratore, and a key figure in the Social

Studies Circle, Pittoni also founded the Workers Cooperative of Trieste, Istria and Friulia.

[1][28]

His

participation in such causes increased the cultural and educational prestige of socialism, solving

many of the movement's teething problems, and helping to spread the cooperative ideals among the

Slovene population.

[29]

He conditioned affiliation to these cooperatives on the desegregation and

inter-ethnic solidarity of candidate unions.

[30]

He also campaigned for the establishment of Workers

Club and an Italian universityin Trieste.

[1]

Pittoni retained his parliamentary seat in the 1911 Austrian general election. This time he was

supported by mainstream Slavic parties, opposed to Felice Venezian's Italian national-liberals,

[18]

but

could not count on the regular Slovene voters, who withdrew their support.

[11]

As leader of the Italian

parliamentary club,

[1][4]

Pittoni supported an inquiry into the affairs of Transleithania, where,

according to fellow deputy George Grigorovici, the Hungarian Post was censoring the

correspondence of left-wing opponents, including Austrian subjects.

[31]

Like the rest of his party, Pittoni issued protests against Rudolf Montecuccoli's plan to modernize

and increase the Austro-Hungarian Navy.

[32]

Together with Adler and with members of the PSI, he

co-founded an anti-war congress that would report on any rearmament on either side of the Italian

Austrian conflict.

[4]

During October 1912, he participated in the mass rallies opposing Austria-

Hungary's involvement in the First Balkan War, and petitioned the government on that subject.

[33]

World War[edit]

The Italian Front in August 1916

In 1914, just before the start of World War I, Pittoni began cooperating with the Yugoslav Social-

Democratic Party (JSDS), which had recently relocated in Trieste, and set up a shared bureau to

oversee common operations. However, he insisted that the common slogan was that of "national

toleration [and] workers solidarity", and that the status of Trieste as an Austrian port could not expect

to change.

[34]

In May 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary. The violence of the subsequent "Mountain War"

demoralized Pittoni,

[35]

who pleaded with his government for the fair treatment of Italian captives and

refugees.

[1]

He and the Slovene Henrik Tumaconceived of an abortive plan to establish a bi-national

Trieste as part of the Austrian monarchy.

[36]

It was to includeMonfalcone, San Dorligo della

Valle, Muggia and other rural localities, which were supposed to form an anti-irredentist cordon of

Slovenes and Friulians.

[37]

In mid 1916, they joined hands with other JSDS moderates,

reestablishing the newspaper Zarja, which, against the SDAP party line, advocated the end of

war.

[38]

The PittoniTuma project was opposed by the Yugoslavistwing of the JSDS, whose

leader Josip Ferfolja accused the internationalists of facilitating the his people's "death as a

nation".

[39]

Probably as a result of this nonconformism, Pittoni was again conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian

Army and sent to the front, before returning to Trieste as cooperative leader, working to ensure the

city's supply in food and basic goods.

[40]

He regained his seat in the Imperial Council in summer

1917, when it reopened its sessions,

[41]

and declared himself willing to represent the Austrian

workers at an international peace conference that was planned in Stockholm.

[42]

At odds with Adler,

who supported continuing the war, he moved closer to Karl Renner's faction, which stood by the old

confederation programme, but he also issued messages of sympathy toward the

revolutionary, Bolshevik and "maximalist", groups.

[43]

He notably demanded freedom for Adler's

son Friedrich, jailed for his assassination of Minister-President von Strgkh.

[44]

Faced with the challenges of Yugoslavism and Austro-Hungarian dissolution, Pittoni called for the

creation of an independent Istrian state

[45]

or a "Republic of Venezia Giulia".

[46]

It was to demand

protection from the League of Nations,

[47]

but Pittoni also spoke of other diplomatic alternatives,

including an American or a Bolshevik occupation.

[48]

In late 1918, as the Slovene National Council

prepared to assume control of the region, he publicized the manifesto of Emperor Charles, which

proposed an Austrian confederation and a special role for Trieste.

[49]

However, he faced increased

opposition within the Trieste socialist movement from the Giuseppe TuntarIvan Regent faction

(which favoured an Italo-Slavic Soviet Republic)

[46]

and from irredentist or "socialist-nationalists"

such as Edmondo Puecher, who had organised the strike of January 1918.

[8]

He responded by

purging Il Lavoratorestaff of suspected irredentists, including writer Bruno Piazza.

[8]

In October 1918, during the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, the Imperial Council's Italian club dissolved: a

"national fascio" was formed, unilaterally proclaiming the annexation of Istria and South Tyrol by the

Kingdom of Italy. Pittoni condemned the move, as did the Friulian deputies Luigi

Faidutti and Giuseppe Bugatto.

[50]

However, he agreed to become a member of the Italian deputies'

Permanent Commission, which was led by the fascio's spokesman, Enrico Conci.

[51]

Although

stranded in Vienna, he communicated with his Triestine faction: his second-in-command, Alfredo

Callini, was a member of the Committee of Public Safety, formed after Governor Alfred von Fries-

Skene abandoned Trieste.

[52]

Pittoni had by then lost all footing inside the JSDS, with Ferfolja

accusing him of being a covert irredentist.

[53]

Exile[edit]

In 1919, Pittoni protested as the Arditi and the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento took over in

Trieste.

[54]

The city was soon placed under the governorship of Carlo Petitti di Roreto, who tried to

talk Pittoni into accepting the national unification and the Trieste Social Democratic League's

integration with the PSI.

[55]

By mid 1919 many of Pittoni's followers, Callini included, had deserted to

the irredentist camp.

[56][50]

Pittoni himself radicalised his opposition to Italian integration, and from

1920 argued that Trieste should form a state within the new Republic of Austria.

[57]

In 1922 Pittoni resigned from his posts in the party, complaining that the socialist movement had

fallen prey to "the most arrogant and greedy kind of capitalism".

[58]

By then, he had lost control of Il

Lavoratore to a Bolshevik faction which was eventually absorbed into the Italian Communist

Party.

[59]

Pittoni moved to Milan, where he managed a Consorzio Italiano consumers

cooperative.

[1][60]

He campaigned for the unification of Italian cooperatives into "a few hundred

powerful organisms", which, as he explained in a February 1922 article for La Cooperazione

Siciliana, were to form the basis of "a new society".

[61]

His daughter Bianca (born in Trieste on March

20, 1904) also became politically active, joiningAnna Kuliscioff's socialist circle in Milan.

[62]

Pittoni remained in Italy after the fascist coup, but was eventually driven out by the regime's violent

actions in 1925.

[63]

He moved back to Vienna, and lived the rest of his life in relative

poverty.

[1]

Granted protection by the municipal government of Karl Seitz,

[64]

he became editor of

the Arbeiter-Zeitung.

[1][65]

Like other Italian emigrants, among themAngelica Balabanoff, he managed

to influence SDAP doctrines, contributing to its strong show of anti-fascism.

[66]

In the conflict

between Italian resistance groups, Pittoni raised funds for Filippo Turati's United Socialists.

[67]

Bianca

Pittoni, who also left Italy in 1927, became Turati's secretary and confidante, and then worked

with Giuseppe Saragat in Vienna.

[62]

Such activities irritated Benito Mussolini, the Italian fascist

leader, who repeatedly urged the Austrian Christian Social Party to liquidate the Viennese socialist

"canker".

[66]

Pittoni died in Vienna on April 11, 1933.

[1][4]

The funeral oration was given by SDAP

colleague Wilhelm Ellenbogen, who called Pittoni's fight against irredentism "one of the most

glorious actions in the history of Austria's workers movement", and praised his "intimate affinity with

the Austro-German thought and sentiment".

[68]

As argued by researcher Gilbert Bosetti, Pittoni's

death "put an end to all hopes of a reform-minded Triestine socialism that supported peace among

peoples."

[58]

Bianca went on to fight for the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. During World War II,

pursued by OVRA and the Gestapo, she joined the French Resistance inPoitou-Charentes.

[62]

From

1944, she was employed by the Embassy of the Republic of Italy in Paris, where she died in

1993.

[62]

Pittoni's other relatives were still residing in Italian Trieste, and then in the Free Territory.

They include his other daughter, Nerina,

[69]

and his niece Anita Pittoni, founder of Lo Zibaldone

publishing house.

[70]

Nerina's son, Luciano Manfredi, was Anita Pittoni's heir.

[69]

Notes[edit]

1. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

j

k

l

m

E. Maserati, "Pittoni, Valentino (18721933), Politiker", entry in

the sterreichisches Biographisches Lexikon 18151950, Vol. 8

2. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

c

Giuseppe Piemontese (1974). Il Movimento operaio a Trieste: dalle origini all'

avvento del fascismo.... Editori Riuniti. p. 146.

3. Jump up^ Bosetti, p. 195

4. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

c

d

e

f

Klinger, p. 85

5. Jump up^ Cuomo, pp. 3132, 72; Klinger, pp. 8588

6. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 8586; Sluga, p. 24

7. Jump up^ Apih, pp. 9295; Bosetti, pp. 197198; Cuomo, pp. 3132; Klinger, pp. 85, 88, 105,

108109

8. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

c

Risa B. Sodi (2007). Narrative and Imperative: The First Fifty Years of Italian

Holocaust Writing (19441994). Peter Lang AG. pp. 9293. ISBN 978-0-8204-8872-1.

9. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

"Congresul internaional socialist". Tribuna Poporului (Arad). May 25, 1905. p. 4.

10. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

c

Labour History Review. Society for the Study of Labour History. 1992. p. 22.

11. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Cuomo, p. 32

12. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 8283

13. Jump up^ Sondhaus, pp. 154155

14. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Graeme Morton; Robert John Morris; B. M. A. de Vries (2006). Civil Society,

Associations, and Urban Places: Class, Nation, and Culture in Nineteenth-century Europe.

Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7546-5247-2.

15. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

c

Laurence Cole (July 1, 2014). Military Culture and Popular Patriotism in Late

Imperial Austria. Oxford University Press. pp. 208, 234. ISBN 978-0-19-967204-2.

16. Jump up^ Eduard Winkler (2000). Wahlrechtsreformen und Wahlen in Triest 19051909: eine

Analyse der politischen Partizipation in einer multinationalen Stadtregion der

Habsburgermonarchie. Oldenbourg Verlag. p. 84. ISBN 978-3-486-56486-0.

17. Jump up^ Sluga, p. 24

18. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Vasilij Melik (January 1, 1997). Wahlen im alten sterreich: am Beispiel der

Kronlnder mit slowenischsprachiger Bevlkerung. Bhlau Verlag Wien. pp. 305, 406.ISBN 978-

3-205-98063-6.

19. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Klinger, p. 87

20. Jump up^ Bosetti, p. 199

21. Jump up^ "Austriacii cer votul universal pentru Ungaria". Tribuna Poporului (Arad). October 13,

1908. p. 4.

22. Jump up^ "Coroana i votul universal". Tribuna Poporului (Arad). September 30, 1908. p. 1-3.

23. Jump up^ Apih, pp. 9293; Cuomo, pp. 3132

24. Jump up^ Bosetti, p. 240

25. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

"Aperto dissenso fra socialisti d'Austria e socialisti d'Italia". Il Paese (248)

(Udine). October 19, 1908. p. 1.

26. Jump up^ Cuomo, pp. 3132

27. Jump up^ Bosetti, p. 205

28. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 87, 88

29. Jump up^ Apih, pp. 9293; Klinger, pp. 8788, 110

30. Jump up^ Apih, p. 92

31. Jump up^ Graur, p. 444

32. Jump up^ Sondhaus, p. 196

33. Jump up^ Raimund Lw (1988). "Die deutsche Sozialdemokratie in sterreich und die

Balkankriege 1912/1913". In Frits van Holthoon; Marcel van der Linden.Internationalism in the

Labour Movement: 18301940, II. E. J. Brill. pp. 413414.ISBN 90-04-08635-8.

34. Jump up^ Apih, pp. 9495

35. Jump up^ Bosetti, p. 267

36. Jump up^ Bosetti, p. 267; Pirjevec, pp. 82, 86

37. Jump up^ Pirjevec, p. 82

38. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 9597

39. Jump up^ Kacin-Wohinz, p. 116

40. Jump up^ Klinger, p. 97

41. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 85, 87

42. Jump up^ Pirjevec, p. 83

43. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 97, 100101

44. Jump up^ Klinger, p. 101

45. Jump up^ Alessi, pp. 29, 34; Kacin-Wohinz, pp. 115118; Bosetti, p. 267

46. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Sluga, p. 41

47. Jump up^ Sluga, p. 41; Kacin-Wohinz, p. 118

48. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 100101

49. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 106107

50. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Branko Marui (2000). "Gli sloveni di Trieste e del Goriziano alla fine della

prima guerra mondiale". Il Territorio (Consorzio Culturale del Monfalconese) 13: 11-12. Retrieved

July 19, 2014.

51. Jump up^ Sergio Benvenuti; Andreina Mascagni (1999). "L'archivio della famiglia

Conci".Archivio Trentino (Museo Storico in Trento) 49 (2): 120. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

52. Jump up^ Alessi, pp. 2834

53. Jump up^ Kacin-Wohinz, p. 119

54. Jump up^ Bosetti, p. 270

55. Jump up^ Alessi, pp. 2830; Cuomo, pp. 7172

56. Jump up^ Alessi, pp. 2930; Klinger, p. 85; Sluga, p. 41

57. Jump up^ Sluga, p. 38

58. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Bosetti, p. 269

59. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 111112

60. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 85, 114; Bosetti, p. 269

61. Jump up^ Eugenio Guccione (1993). "Il giornalismo cooperativistico". In Orazio Cancila. Storia

della cooperazione siciliana. Istituto regionale per il credito alla cooperazione.

p. 509.OCLC 797874034.

62. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

c

d

Giuseppe Muzzi, "Pittoni, Bianca, politica", biographical profile in SIUSA:

Archivi di personalit. Censimento dei fondi toscani tra '800 e '900. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

63. Jump up^ Cuomo, p. 127; Klinger, pp. 85, 108109, 114; Graur, p. 446

64. Jump up^ Cuomo, p. 127

65. Jump up^ Miriam Coen (January 1, 1995). Bruno Pincherle. Edizioni Studio Tesi.

p. 19.ISBN 978-88-7692-495-8. Graur, p. 446; Klinger, p. 85

66. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Diego Cante (2009). "Gli incontri di calcio tra Italia e Austria tra le due guerre". In

Maria Canella; Sergio Giuntini. Sport e fascismo. FrancoAngeli. p. 161. ISBN 978-88-568-1510-

8.

67. Jump up^ Carmela Maltone (2013). "Scrivere contro. I giornali antifascisti italiani in Francia dal

1922 al 1943". Line@editoriale (University of Toulouse) 5. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

68. Jump up^ Klinger, pp. 108109

69. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

"Fondo Anita Pittoni", entry in the Catalogo integrato dei beni culturali,

Commune of Trieste. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

70. Jump up^ Katia Pizzi (2001). A City in Search of an Author. Sheffield Academic Press.

p. 164.ISBN 1-84127-284-1. Sluga, p. 226

References[edit]

Chino Alessi (1993). Rino Alessi. Edizioni Studio Tesi. ISBN 88-7692-369-1.

Elio Apih (1979). "Sui rapporti tra socialisti italiani e socialisti sloveni nella regione Giulia (1888

1917)". Prispevki za zgodovino delavskega gibanja, Letnik XVII. Intitut za zgodovino

delavskega gibanja. pp. 8996. OCLC 11668604.

Gilbert Bosetti (2006). De Trieste Dubrovnik: une ligne de fracture de l'Europe.

ELLUG. ISBN 978-2-84310-080-2.

Pasquale Cuomo (2012). Il miraggio danubiano: Austria e Italia, politica ed economia, 1918

1936. FrancoAngeli. ISBN 978-8820411480.

Constantin Graur (1935). Cu privire la Franz Ferdinand. Adevrul. OCLC 34613821.

Milica Kacin-Wohinz (1979). "I socialisti sloveni di Trieste nel 1918". Prispevki za zgodovino

delavskega gibanja, Letnik XVII. Intitut za zgodovino delavskega gibanja. pp. 113

121. OCLC 11668604.

William Klinger (2012). "Crepuscolo adriatico. Nazionalismo e socialismo italiano in Venezia

Giulia (18961945)". Quaderni (Centro Ricerche Storiche Rovigno) 23: 79126. Retrieved July

19, 2014.

Joe Pirjevec (1979). "Henrik Tuma e il socialismo". Prispevki za zgodovino delavskega gibanja,

Letnik XVII. Intitut za zgodovino delavskega gibanja. pp. 7587.OCLC 11668604.

Glenda Sluga (January 11, 2001). The Problem of Trieste and the Italo-Yugoslav Border:

Difference, Identity, and Sovereignty in Twentieth-Century Europe. SUNY Press.ISBN 978-0-

7914-4824-3.

Lawrence Sondhaus (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 18671918: Navalism,

Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. Purdue University Press.ISBN 978-1-55753-

034-9.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hitler and the Forgotten Nazis: A History of Austrian National SocialismVon EverandHitler and the Forgotten Nazis: A History of Austrian National SocialismBewertung: 2.5 von 5 Sternen2.5/5 (3)

- Support For The War: OntentsDokument3 SeitenSupport For The War: OntentsLEONHARD COHENNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tito-Stalin Split and Its Consequences: Christoffer M. Andersen Central Europe & Stalin Winter 2004Dokument11 SeitenThe Tito-Stalin Split and Its Consequences: Christoffer M. Andersen Central Europe & Stalin Winter 2004shwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HIST 102 Exam 2Dokument7 SeitenHIST 102 Exam 2William QuillenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mussolini as revealed in his political speeches, November 1914-August 1923Von EverandMussolini as revealed in his political speeches, November 1914-August 1923Noch keine Bewertungen

- Failure of 1820-1830 Revolutions in ItalyDokument3 SeitenFailure of 1820-1830 Revolutions in Italysamsyed23100% (1)

- Communism and anti-Communism in early Cold War Italy: Language, symbols and mythsVon EverandCommunism and anti-Communism in early Cold War Italy: Language, symbols and mythsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Austria and 1938Dokument1 SeiteAustria and 1938Schannasp8Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Priest at The Front. Jozef Tiso Changi PDFDokument22 SeitenA Priest at The Front. Jozef Tiso Changi PDFLenthár BalázsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tito The Formation of A Disloyal BolshevikDokument24 SeitenTito The Formation of A Disloyal BolshevikMarijaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti-Russian Nationalism in The Baltic States: On The 60th Anniversary of The Victory of The Red Army Over NazismDokument2 SeitenAnti-Russian Nationalism in The Baltic States: On The 60th Anniversary of The Victory of The Red Army Over NazismShane MishokaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Winston Churchill: Contemporary British History November 2017Dokument9 SeitenWinston Churchill: Contemporary British History November 2017EmanuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 12Dokument46 SeitenChapter 121federalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timeline of Key Events - Paper 1 - The Move To Global War Italy and Germany 1933-1940Dokument10 SeitenTimeline of Key Events - Paper 1 - The Move To Global War Italy and Germany 1933-1940victormwongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rise of Fascism and NazismDokument12 SeitenRise of Fascism and NazismMatías Rodríguez .-.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Georg Ritter Von Schönerer: Supporting Memorandum Supporting MemorandumDokument9 SeitenGeorg Ritter Von Schönerer: Supporting Memorandum Supporting MemorandumBogdanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Age of Dictatorship: Europe 1918-1989 - The Little Dictators TranscriptDokument8 SeitenThe Age of Dictatorship: Europe 1918-1989 - The Little Dictators TranscriptKlaudia MendyczkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Support For The War: Poster Urging Women To Join The British War Effort, Published by TheDokument3 SeitenSupport For The War: Poster Urging Women To Join The British War Effort, Published by TheLEONHARD COHENNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jenő VargaDokument46 SeitenJenő Varga1federalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paolo Casciola: Italian TrtotskyismDokument63 SeitenPaolo Casciola: Italian TrtotskyismAnonymous Pu2x9KVNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study 2: German AND Italian ExpansionDokument12 SeitenCase Study 2: German AND Italian ExpansionLea Charlotte Wingerden vanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1914 1918 Online Interventionism - Italy 2016 06 10Dokument3 Seiten1914 1918 Online Interventionism - Italy 2016 06 10ilmioahuhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rise of Fascism and Nazism PDFDokument5 SeitenThe Rise of Fascism and Nazism PDFhistory 2BNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Relationship Between Hitler and MussoliniDokument6 SeitenThe Relationship Between Hitler and MussoliniAlina-Andrea ArdeleanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timeline For Italian and German ExpansionDokument10 SeitenTimeline For Italian and German ExpansionFlor AliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rise of Fascism in Italy and Nazism in Germany: A Comparitive StudyDokument22 SeitenRise of Fascism in Italy and Nazism in Germany: A Comparitive StudyMoon MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rise of Nationalism in The Contemporary European PoliticsDokument22 SeitenRise of Nationalism in The Contemporary European Politicsanitta joseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Year 12 Modern History Soviet Foreign Policy 1917 41 ADokument2 SeitenYear 12 Modern History Soviet Foreign Policy 1917 41 ANyasha chadebingaNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Joseph Stalin - Premier of Union of Soviet Socialist Republics"Dokument4 Seiten"Joseph Stalin - Premier of Union of Soviet Socialist Republics"Va SylNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ib History Wwii PreviewDokument4 SeitenIb History Wwii Previewdavidtrump3440100% (1)

- The Mustard Gas WarDokument31 SeitenThe Mustard Gas WarAlan Challoner100% (1)

- Research Paper in Mapeh: Submitted To:sir Richard Gabilo By:John Robert E. NarcisoDokument5 SeitenResearch Paper in Mapeh: Submitted To:sir Richard Gabilo By:John Robert E. NarcisoKang ArnoldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fascism in ItalyDokument15 SeitenFascism in Italyhistory 2BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q&A Nationalism 1815-70Dokument3 SeitenQ&A Nationalism 1815-70nyoman_pandeNoch keine Bewertungen

- AxisDokument51 SeitenAxisbakex645Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bento MussoliniDokument8 SeitenBento MussoliniMohit VermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fascism in ItalyDokument14 SeitenFascism in ItalyFlavia Andreea SavinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilhelm StuckartDokument4 SeitenWilhelm StuckartChristosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Causes of Rise of Fascism in ItalyDokument10 SeitenCauses of Rise of Fascism in ItalyTaimur KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resistenza - Articolo ERASDokument8 SeitenResistenza - Articolo ERASMax LiviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nazis Germany Political Science Prof. Martin SviatkoDokument33 SeitenNazis Germany Political Science Prof. Martin SviatkoLinyVatNoch keine Bewertungen

- ATA II, Course VaI (Interwar Period)Dokument33 SeitenATA II, Course VaI (Interwar Period)y SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fascism Is One of The Most Important and Also Controversial Phenomena of Modern History As There IsnDokument3 SeitenFascism Is One of The Most Important and Also Controversial Phenomena of Modern History As There IsnSrishti kashyapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fascism and NazismDokument12 SeitenFascism and NazismAruni SinhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ussr Ii Russian Foreign Policy AcademiaDokument20 SeitenUssr Ii Russian Foreign Policy AcademiaBidisha MaharanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Otto Strasser and National Socialism GottfriedDokument10 SeitenOtto Strasser and National Socialism Gottfriedgiorgoselm100% (1)

- Rise of Facism WorksheetDokument3 SeitenRise of Facism Worksheetanfal azamNoch keine Bewertungen

- A3. Mussolini's Political OdysseyDokument3 SeitenA3. Mussolini's Political OdysseyTehreem ChNoch keine Bewertungen

- FascismDokument8 SeitenFascismPreeti KumariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forlenza - Between East and WestDokument31 SeitenForlenza - Between East and WestdaviesmaxspamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sage Publications, LTDDokument18 SeitenSage Publications, LTDerezdavNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Anschluss With AustriaDokument1 SeiteThe Anschluss With Austriachl23Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pactul TripartitDokument8 SeitenPactul Tripartittodo_laura2005Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fascism in ItalyDokument6 SeitenFascism in ItalyPathias Matambo0% (2)

- Trotsky - Robert ServiceDokument4 SeitenTrotsky - Robert ServicepabloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 1 E3 The Collapse of The Liberal State and The Triumph of Fascism in ItalyDokument32 SeitenUnit 1 E3 The Collapse of The Liberal State and The Triumph of Fascism in ItalyTrisha KhannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Working With The Enemy The Relationship Between Italian Partisans and British ForcesDokument8 SeitenWorking With The Enemy The Relationship Between Italian Partisans and British ForcesBob CookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strasserism in DepthDokument42 SeitenStrasserism in DepthSouthern FuturistNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saving SAT (First) and ACT (Second) Scores Into A PDFDokument6 SeitenSaving SAT (First) and ACT (Second) Scores Into A PDFJāfri WāhidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Strategies Used by The BanksDokument20 SeitenMarketing Strategies Used by The BanksJāfri Wāhid100% (1)

- Banking Industry of BangladeshDokument26 SeitenBanking Industry of BangladeshJāfri WāhidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internship Report of IFIC BankDokument40 SeitenInternship Report of IFIC BankJāfri WāhidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internship Affiliation Report On Bank AsiaDokument42 SeitenInternship Affiliation Report On Bank AsiaJāfri Wāhid100% (1)

- First Homecoming C10Dokument10 SeitenFirst Homecoming C10Jomer MesiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vișan-Miu Tudor - Mauriciu BrocinerDokument20 SeitenVișan-Miu Tudor - Mauriciu BrocinertudorvisanmiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Growth of Feminist Foreign Policy PDFDokument3 SeitenThe Growth of Feminist Foreign Policy PDFNatasya AmazingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Extra O. Gazette No. 195 EC Parliamentary Results 2020Dokument86 SeitenExtra O. Gazette No. 195 EC Parliamentary Results 2020Fuaad DodooNoch keine Bewertungen

- KUWAIT Hospital ListDokument7 SeitenKUWAIT Hospital ListenquiryNoch keine Bewertungen

- St. Johns County Candidate List Aug. 18 2020Dokument10 SeitenSt. Johns County Candidate List Aug. 18 2020First Coast NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparison of Noli Me Tangere and El FilibusterismoDokument11 SeitenComparison of Noli Me Tangere and El FilibusterismoJessa Mae SusonNoch keine Bewertungen

- BADDENAPALLYDokument5 SeitenBADDENAPALLYlaxmisrclNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nag D - Bengali Popular Films Since 1950Dokument10 SeitenNag D - Bengali Popular Films Since 1950arunodaymajumderNoch keine Bewertungen

- India and Post-Colonial DiscourseDokument8 SeitenIndia and Post-Colonial Discourseankitabehera0770% (1)

- Oral CommDokument1 SeiteOral CommShanley MarieNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2021.07.21 Our Report On Russian Interference - UpdatedDokument12 Seiten2021.07.21 Our Report On Russian Interference - UpdatedFaireSansDireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geopolitical Significance of Afghanistan A Reappraised EpistemeDokument3 SeitenGeopolitical Significance of Afghanistan A Reappraised EpistemeInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drept Administrativ Volumul II Ed.4 - Dana Apostol TofanDokument12 SeitenDrept Administrativ Volumul II Ed.4 - Dana Apostol TofanIonela Huidiu0% (1)

- 845-Article Text-3105-1-10-20231107Dokument9 Seiten845-Article Text-3105-1-10-20231107daesha putriNoch keine Bewertungen

- தரம் 7 PDFDokument46 Seitenதரம் 7 PDFஅகரம் தினேஸ்Noch keine Bewertungen

- Israel and Turkey: Once Comrades Now Frenemies: Tuğçe Ersoy CeylanDokument18 SeitenIsrael and Turkey: Once Comrades Now Frenemies: Tuğçe Ersoy CeylanAdilkhan GadelshiyevNoch keine Bewertungen

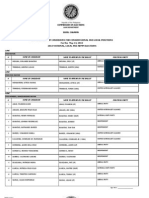

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDokument2 SeitenCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1) Define Essence of WarDokument7 Seiten1) Define Essence of Warმარიამ კაკაჩიაNoch keine Bewertungen

- LP Report Chapter 8Dokument27 SeitenLP Report Chapter 8Gem Boy HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laporan Pertanggungjawaban Pramuka MengajarDokument11 SeitenLaporan Pertanggungjawaban Pramuka MengajarDanik FitriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Placencia'S Code On The Ancient Customs of The TAGALOGS (1589)Dokument16 SeitenPlacencia'S Code On The Ancient Customs of The TAGALOGS (1589)Lee HoseokNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federalists Vs Democratic RepublicansDokument2 SeitenFederalists Vs Democratic RepublicansVioletNoch keine Bewertungen

- LTC Form 2 Aclo Lot 4412-BDokument2 SeitenLTC Form 2 Aclo Lot 4412-BJaypee Semeni ApitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Othello EssayDokument2 SeitenOthello Essayapi-402675684Noch keine Bewertungen

- ????? ????????? ?????Dokument20 Seiten????? ????????? ?????minaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 750 Words With ReferenceDokument2 Seiten750 Words With ReferenceNight BallNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journals PPSJ 33 2 Article-P255 12-PreviewDokument2 SeitenJournals PPSJ 33 2 Article-P255 12-PreviewCjES EvaristoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gandhi Radical KinshipDokument15 SeitenGandhi Radical KinshipGlauco FerreiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dewey View On Religion.Dokument17 SeitenDewey View On Religion.GeeKinqestNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary: Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties by Tom O’ Neill & Dan Piepenbring: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties by Tom O’ Neill & Dan Piepenbring: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (2)

- Say More: Lessons from Work, the White House, and the WorldVon EverandSay More: Lessons from Work, the White House, and the WorldBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sVon EverandAn Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)

- For Love of Country: Leave the Democrat Party BehindVon EverandFor Love of Country: Leave the Democrat Party BehindBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (5)

- Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesVon EverandSon of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (506)

- The War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionVon EverandThe War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Broken Money: Why Our Financial System Is Failing Us and How We Can Make It BetterVon EverandBroken Money: Why Our Financial System Is Failing Us and How We Can Make It BetterBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (5)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentVon EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (9)

- Revenge: How Donald Trump Weaponized the US Department of Justice Against His CriticsVon EverandRevenge: How Donald Trump Weaponized the US Department of Justice Against His CriticsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (60)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldVon EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (1147)

- Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorVon EverandBind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (77)

- Financial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassVon EverandFinancial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benjamin Franklin: An American LifeVon EverandBenjamin Franklin: An American LifeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (152)

- Pagan America: The Decline of Christianity and the Dark Age to ComeVon EverandPagan America: The Decline of Christianity and the Dark Age to ComeBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- How to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsVon EverandHow to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (21)

- You Can't Joke About That: Why Everything Is Funny, Nothing Is Sacred, and We're All in This TogetherVon EverandYou Can't Joke About That: Why Everything Is Funny, Nothing Is Sacred, and We're All in This TogetherNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Return of George Washington: Uniting the States, 1783–1789Von EverandThe Return of George Washington: Uniting the States, 1783–1789Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (22)

- Compromised: Counterintelligence and the Threat of Donald J. TrumpVon EverandCompromised: Counterintelligence and the Threat of Donald J. TrumpBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (18)

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaVon EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (23)

- Thomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaVon EverandThomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (107)

- Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowVon EverandHeretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (57)

- Darkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the BrinkVon EverandDarkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the BrinkBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (31)

- The Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpVon EverandThe Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (11)

- Franklin & Washington: The Founding PartnershipVon EverandFranklin & Washington: The Founding PartnershipBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (14)