Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

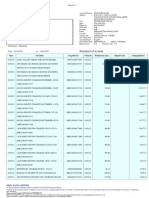

Labor Law Case Digests

Hochgeladen von

tweezy240 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

104 Ansichten9 Seitencase digests

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldencase digests

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

104 Ansichten9 SeitenLabor Law Case Digests

Hochgeladen von

tweezy24case digests

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 9

NITTO ENTERPRISES, vs.

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION and ROBERTO CAPILI,

G.R. No. 114337 September 29, 1995

FACTS: Petitioner Nitto Enterprises, a company engaged in the sale of glass and aluminum products,

hired Roberto Capili sometime in May 1990 as an apprentice machinist, molder and core maker as

evidenced by an apprenticeship agreement for a period of six (6) months from May 28, 1990 to

November 28, 1990 with a daily wage rate of P66.75 which was 75% of the applicable minimum wage.

At around 1:00 p.m. of August 2, 1990, Roberto Capili who was handling a piece of glass which he was

working on, accidentally hit and injured the leg of an office secretary who was treated at a nearby

hospital.

Later that same day, after office hours, private respondent entered a workshop within the office

premises which was not his work station. There, he operated one of the power press machines without

authority and in the process injured his left thumb. Petitioner spent the amount of P1,023.04 to cover

the medication of private respondent. On August 3, 1990 private respondent executed a Quitclaim and

Release in favor of petitioner for and in consideration of the sum of P1,912.79. Three days after, or on

August 6, 1990, private respondent formally filed before the NLRC Arbitration Branch, National Capital

Region a complaint for illegal dismissal and payment of other monetary benefits. On October 9, 1991,

the Labor Arbiter rendered his decision finding the termination of private respondent as valid and

dismissing the money claim for lack of merit.

Labor Arbiter Patricio P. Libo-on gave two reasons for ruling that the dismissal of Roberto Capilian was

valid. First, private respondent who was hired as an apprentice violated the terms of their agreement

when he acted with gross negligence resulting in the injury not only to himself but also to his fellow

worker. Second, private respondent had shown that "he does not have the proper attitude in

employment particularly the handling of machines without authority and proper training.

On July 26, 1993, the NLRC issued an order reversing the decision of the Labor Arbiter the appealed

decision is hereby set aside. The respondent is hereby directed to reinstate complainant to his work last

performed with backwages computed from the time his wages were withheld up to the time he is

actually reinstated. The Arbiter of origin is hereby directed to further hear complainant's money claims

and to dispose them on the basis of law and evidence obtaining.

On January 28, 1994, Labor Arbiter Libo-on called for a conference at which only private respondent's

representative was present. On April 22, 1994, a Writ of Execution was issued, finding merit in [private

respondent's] Motion for Issuance of the Writ, The private respondent is being commanded to proceed

to the premises of [petitioner] Nitto Enterprises and Jovy Foster located at No. l 74 Araneta Avenue,

Portero, Malabon, Metro Manila or at any other places where their properties are located and effect the

reinstatement of herein [private respondent] to his work last performed or at the option of the

respondent by payroll reinstatement.

He is also entitled to collect the amount of P122,690.85 representing his backwages as called for in the

dispositive portion, and turn over such amount to this Office for proper disposition.Petitioner filed a

motion for reconsideration but the same was denied.

ISSUES: 1. WHETHER OR NOT PUBLIC RESPONDENT NLRC COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN

HOLDING THAT PRIVATE RESPONDENT WAS NOT AN APPRENTICE.

2. WHETHER OR NOT PUBLIC RESPONDENT NLRC COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN

HOLDING THAT PETITIONER HAD NOT ADEQUATELY PROVEN THE EXISTENCE OF A VALID CAUSE IN

TERMINATING THE SERVICE OF PRIVATE RESPONDENT.

HELD: There is an abundance of cases wherein the Court ruled that the twin requirements of due

process, substantive and procedural, must be complied with, before valid dismissal exists. Without

which, the dismissal becomes void. The fact is private respondent filed a case of illegal dismissal with the

Labor Arbiter only three days after he was made to sign a Quitclaim, a clear indication that such

resignation was not voluntary and deliberate.

Private respondent averred that he was actually employed by petitioner as a delivery boy ("kargador" or

"pahinante"). He further asserted that petitioner "strong-armed" him into signing the aforementioned

resignation letter and quitclaim without explaining to him the contents thereof. Petitioner made it clear

to him that anyway, he did not have a choice.

Petitioner cannot disguise the summary dismissal of private respondent by orchestrating the latter's

alleged resignation and subsequent execution of a Quitclaim and Release. A judicious examination of

both events belies any spontaneity on private respondent's part.

The court finds no abuse of discretion committed by public respondent National Labor Relations

Commission, the appealed decision is hereby AFFIRMED.

MANILA TERMINAL CO. INC. v. CIR G.R. No. L-4148 July 16, 1952

FACTS: Manila Terminal Company, Inc. undertook the arrastre service in some of the piers in Manila's

Port Area at the request and under the control of the United States Army. The petitioner hired some

thirty men as watchmen on twelve-hour shifts at a compensation of P3 per day for the day shift and P6

per day for the night shift. The watchmen of the petitioner continued in the service with a number of

substitutions and additions, their salaries having been raised during the month of February to P4 per day

for the day shift and P6.25 per day for the nightshift. The private respondent sent a letter to Department

of Labor requesting that the matter of overtime pay be investigated. But nothing was done by the

Department of Labor.

Later on, the petitioner instituted the system of strict eight-hour shifts. The private respondent filed an

amended petition with the CIR praying, among others, that the petitioner be ordered to pay its

watchmen or police force overtime pay from the commencement of their employment.

By virtue of Customs Administrative Order No. 81 and Executive Order No. 228 of the President of the

Philippines, the entire police force of the petitioner was consolidated with the Manila Harbor Police of

the Customs Patrol Service, a Government agency under the exclusive control of the Commissioner of

Customs and the Secretary of Finance The Manila Terminal Relief and Mutual Aid Association will

hereafter be referred to as the Association.

Judge V. Jimenez Yanson of the CIR in his decision ordered the petitioner to pay to its police force but

regards to overtime service after the watchmen had been integrated into the Manila Harbor Police, the

has no jurisdiction because it affects the Bureau of Customs, an instrumentality of the Government

having no independent personality and which cannot be sued without the consent of the State.

The petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration. The Association also filed a motion for reconsideration

in so far its other demands were dismissed. Both resolutions were denied.

The public respondent decision was to pay the private respondents their overtime on regular days at the

regular rate and additional amount of 25 percent, overtime on Sundays and legal holidays at the regular

rate only, and watchmen are not entitled to night differential pay for past services. The petitioner has

filed a present petition for certiorari.

ISSUES: 1.) Whether or not the CIR has no jurisdiction to render a money judgment involving obligation

in arrears?

2.) Whether or not the agreement under which its police force were paid certain specific wages for

twelve-hour shifts, included overtime compensation.

3.) Whether or not the nullity or invalidity of the employment contract precludes any recovery by the

Association.

4.) Whether or not the Commonwealth Act No. 4444 does not authorize recovery of back overtime pay.

HELD: The Supreme Court affirmed the appealed decision that the petitioner's watchmen is entitled to

extra compensation only from the dates they respectively entered the service of the petitioner,

hereafter to be duly determined by the Court of Industrial Relations.

1.) The Court of Industrial Relations has no jurisdiction to award a money judgment was already

overruled by this Court on the case of Detective & protective Bureau, Inc. vs. Court of Industrial

Relations and United Employees Welfare Association that under Commonwealth Act No. 103 the Court

is empowered to make the order for the purpose of settling disputes between the employer and

employee.

2.) Based on the case of Detective & Protective Bureau, Inc. vs. Court of Industrial Relations and United

Employees Welfare Association, the law gives them the right to extra compensation. And they could not

be held to have impliedly waived such extra compensation, since it cannot expressly be waived.

3.) The employee in rendering extra service at the request of his employer has a right to assume that the

latter has complied with the requirement of the law, and therefore has obtained the required

permission from the Department of Labor. This was based on the case of Gotamo Lumber Co. vs. Court

of Industrial Relations, wherein both parties are in pari delicto. Moreover, the Eight-Hour Law, in

providing that "any agreement or contract between the employer and the laborer or employee contrary

to the provisions of this Act shall be null avoid ab initio.

4.) Based on Fair Labor Standards Act of the United States which provides that "any employer who

violates the provisions of section 206 and section 207 of this title shall be liable to the employee or

employees affected in the amount of their unpaid minimum wages or their unpaid overtime

compensation as the case may be," a provision not incorporated in Commonwealth Act No. 444, our

Eight-Hour Labor Law.

We cannot agree to the proposition, because sections 3 and 5 of Commonwealth Act 444 expressly

provides for the payment of extra compensation in cases where overtime services are required, with the

result that the employees or laborers are entitled to collect such extra compensation for past overtime

work. To hold otherwise would be to allow an employer to violate the law by simply, as in this case,

failing to provide for and pay overtime compensation.

AUTO BUS TRANSPORT SYSTEMS, INC. vs. ANTONIO BAUTISTA G.R. No. 156367 May 16, 2005

FACTS: Respondent Antonio Bautista has been employed by petitioner Auto Bus Transport Systems, Inc.

(Autobus), as driver-conductor with travel routes Manila-Tuguegarao via Baguio, Baguio- Tuguegarao via

Manila and Manila-Tabuk via Baguio. Respondent was paid on commission basis, 7% of the total gross

income per travel, on a twice a month basis. While he was driving he accidentally bumped the rear

portion of Autobus No. 124. Respondent averred that the accident happened because he was compelled

by the management to go back to Roxas, Isabela, although he had not slept for almost 24 hours, as he

had just arrived in Manila from Roxas, Isabela. Respondent further alleged that he was not allowed to

work until he fully paid the amount of P75,551.50, representing thirty percent (30%) of the cost of repair

of the damaged buses and that despite respondents pleas for reconsideration, the same was ignored by

management. After a month, management sent him a letter of termination. Bautista instituted a

Complaint for Illegal Dismissal with Money Claims for nonpayment of 13th month pay and service

incentive leave pay against Autobus.

ISSUE: Whether or not Bautista, who is paid on purely commission basis, is entitled to the grant of

service incentive leave pay.

HELD: Employees engaged on task or contract basis or purely commission basis are not automatically

exempted from the grant of service incentive leave, unless, they fall under the classification of field

personnel.

Field personnel" is not merely concerned with the location where the employee regularly performs his

duties but also with the fact that the employees performance is unsupervised by the employer. They

are those who regularly perform their duties away from the principal place of business of the employer

and whose actual hours of work in the field cannot be determined ith reasonable certainty. Thus, in

order to conclude whether an employee is a field employee, it is also necessary to ascertain if actual

hours of work in the field can be determined with reasonable certainty by the employer. In so doing, an

inquiry must be made as to whether or not the employees time and performance are constantly

supervised by the employer.

The respondent is not a field personnel but a regular employee who performs tasks usually necessary

and desirable to the usual trade of petitioners business. Accordingly, respondent is entitled to the grant

of service incentive leave. It is of judicial notice that along the routes that are plied by these bus

companies, there are its inspectors assigned at strategic places who board the bus and inspect the

passengers, xxxx. There is also the mandatory once a week car barn or shop day, where the bus is

regularly checked as to its mechanical, electrical xxx. They too, must be at specific place at specified

time, as they generally observe prompt departure and arrival from their point of origin to their point of

destination. In each and every depot, there is always the Dispatcher whose function is precisely to see to

it that the bus and its crew leave the premises at specific times and arrive at the estimated proper time.

These, are present in the case at bar. The driver, the complainant herein, was therefore under constant

supervision while in the performance of this work. He cannot be considered a field personnel.

LABOR CONGRESS OF THE PHILIPPINES V NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION,

FACTS: The 99 persons named as petitioners in this proceeding were rank-and-file employees of

respondent Empire Food Products, which hired them on various dates. Petitioners filed against private

respondents a complaint for payment of money claim[s] and for violation of labor standard[s] laws.

On January 23, 1991, petitioners filed a complaint docketed as NLRC Case No. RAB-III-01- 1964-91

against private respondents for:

After the submission by the parties of their respective position papers and presentation of testimonial

evidence, Labor Arbiter Ariel C. Santos absolved private respondents of the charges of unfair labor

practice, union busting, violation of the memorandum of agreement, underpayment of wages and

denied petitioners' prayer for actual, moral and exemplary damages. Labor Arbiter Santos, however,

directed the reinstatement of the individual complainants:

ISSUE: Whether or not the petitioners are pakyao or per piece workers and therefore not entitled to

benefits as that of a regular employee.

HELD: As to the other benefits, namely, holiday pay, premium pay, 13th month pay and service incentive

leave which the labor arbiter failed to rule on but which petitioners prayed for in their complaint, we

hold that petitioners are so entitled to these benefits. Three (3) factors lead us to conclude that

petitioners, although piece-rate workers, were regular employees of private respondents. First, as to the

nature of petitioners' tasks, their job of repacking snack food was necessary or desirable in the usual

business of private respondents, who were engaged in the manufacture and selling of such food

products; second, petitioners worked for private respondents throughout the year, their employment

not having been dependent on a specific project or season; and third, the length of time that petitioners

worked for private respondents.

Thus, while petitioners' mode of compensation was on a "per piece basis," the status and nature of their

employment was that of regular employees. The Rules Implementing the Labor Code exclude certain

employees from receiving benefits such as nighttime pay, holiday pay, service incentive leave and 13th

month pay, inter alia, "field personnel and other employees whose time and performance is

unsupervised by the employer, including those who are engaged on task or contract basis, purely

commission basis, or those who are paid a fixed amount for performing work irrespective of the time

consumed in the performance thereof." Plainly, petitioners as piece-rate workers do not fall within this

group.

As mentioned earlier, not only did petitioners labor under the control of private respondents as their

employer, likewise did petitioners toil throughout the year with the fulfillment of their quota as

supposed basis for compensation. Further, in Section 8 (b), Rule IV, Book III which we quote hereunder,

piece workers are specifically mentioned as being entitled to holiday pay.

Sec. 8. Holiday pay of certain employees. (b) Where a covered employee is paid by results or output,

such as payment on piece work, his holiday pay shall not be less than his average daily earnings for the

last seven (7) actual working days preceding the regular holiday: Provided, however, that in no case shall

the holiday pay be less than the applicable statutory minimum wage rate.

The Supreme Court in its decision HELD: DECLARING petitioners to have been illegally dismissed by

private respondents, thus entitled to full back wages and other privileges, and separation pay in lieu of

reinstatement at the rate of one month's salary for every year of service with a fraction of six months of

service considered as one year.

University of Pangasinan Faculty Union vs. University of Pangasinan G.R. No. L-63122 Feburuary 20, 1984

FACTS: The petitioners members are full time professors, instructors, and teachers of the respondent

University. The teachers in the college level teach for a normal duration of ten (10) months in a school

year, divided into two (2) semesters of five months each, excluding the two-month summer vacation.

These teachers are paid their salaries on a regular monthly basis.

In November and December, 1981, the petitioners members were fully paid their regular monthly

salaries. However, from November 7 to December 5, during the semestral break, they were not paid

their emergency cost of living allowance(ECOLA). The University claims that the teachers are not entitled

thereto because the semestral break is not an integral part of the school year and there being no actual

services rendered by the teachers during said period, the principle of No work, no pay appllies.

ISSUE: Whether or not petitioner members are not entitled to ECOLA under No work, no pay principle.

HELD: The No work, no pay does not apply in the instant case. The petitioners members received

their regular salaries during this period. It is clear from the aforeqouted provision of the law that it

contemplates a no work situation where the employees voluntarily absent themselves.

Petitioners, in the case at bar certainly do not, ad voluntatem, absent themselves during semestral

breaks. Rather, they are constrained to take mandatory leave from work. For this, they cannot be

faulted nor can they be begrudged that which is due them under the law. To a certain extent, the private

respondent can specify dates when no classes would be held..

Surely, it was no the intention of the framers of the law to allow employers to withhold employee

benefits by simple expedient of unilaterally imposing no work days and consequently avoiding

compliance with the mandate of the law for these days.

Thus, the legal principles of No work, no pay; No pay, no ECOLA must necessarily give way to the

purpose of the law to augment the income of the employees to enable them to cope with the harsh

living conditions brought about by inflation; and to protect employees and their wages against the

ravages brought by these conditions.

Wellington Investment and Manufacturing Corp., vs Trajano G.R. No. 114698 July 3, 1995

FACTS: The case arose from a routine inspection conducted by a Labor Enforcement Officer on August 6,

1991 of the Wellington Flour Mills, an establishment owned and operated by petitioner Wellington

Investment and Manufacturing Corporation (hereafter, simply Wellington). The officer thereafter drew

up a report, a copy of which was "explained to and received by" Wellington's personnel manager, in

which he set forth his finding of "non-payment of regular holidays falling on a Sunday for monthly-paid

employees."

Wellington sought reconsideration of the Labor Inspector's report, by letter dated August 10, 1991.

However, respondents arguments failed to persuade the Regional Director who, in an Order issued on

July 28, 1992, ruled and accordingly directed Wellington to pay its employees compensation

corresponding to four (4) extra working days. Wellington timely filed a motion for reconsideration of this

Order of August 10, 1992. Its motion was treated as an appeal and was acted on by respondent

Undersecretary. By Order dated September 22, the latter affirmed the challenged order of the Regional

Director." Again, Wellington moved for reconsideration, and again was rebuffed.

Wellington then instituted the special civil action of certiorari at bar in an attempt to nullify the orders

above mentioned. By Resolution dated July 4, 1994, this Court authorized the issuance of a temporary

restraining order enjoining the respondents from enforcing the questioned orders.

ISSUE: Whether a monthly-paid employee, receiving a fixed monthly compensation, is entitled to an

additional pay aside from his usual holiday pay, whenever a regular holiday falls on a Sunday

HELD: Every worker should, according to the Labor Code, "be paid his regular daily wage during regular

holidays, except in retail and service establishments regularly employing less than ten workers;" this, of

course, even if the worker does no work on these holidays. Particularly as regards employees "who are

uniformly paid by the month, "the monthly minimum wage shall not be less than the statutory minimum

wage multiplied by 365 days divided by twelve." This monthly salary shall serve as compensation "for all

days in the month whether worked or not," and "irrespective of the number of working days therein." .

So, too, in the event of the declaration of any special holiday, or any fortuitous cause precluding work on

any particular day or days (such as transportation strikes, riots, or typhoons or other natural calamities),

the employee is entitled to the salary for the entire month and the employer has no right to deduct the

proportionate amount corresponding to the days when no work was done. The monthly compensation

is evidently intended precisely to avoid computations and adjustments resulting from the contingencies

just mentioned which are routinely made in the case of workers paid on daily basis.

In Wellington's case, no issue that to this extent, it complied with the minimum norm laid down by law.

Apparently the monthly salary was fixed by Wellington to provide for compensation for every working

day of the year including the holidays specified by law and excluding only Sundays. In fixing the salary,

Wellington used what it calls the "314 factor;" that is to say, it simply deducted 51 Sundays from the 365

days normally comprising a year and used the difference, 314, as basis for determining the monthly

salary. The monthly salary thus fixed actually covers payment for 314 days of the year, including regular

and special holidays, as well as days when no work is done by reason of fortuitous cause, as above

specified, or causes not attributable to the employees.

There is no provision of law requiring any employer to make such adjustments in the monthly salary rate

set by him to take account of legal holidays falling on Sundays in a given year, or, contrary to the legal

provisions bearing on the point, otherwise to reckon a year at more than 365 days. As earlier

mentioned, what the law requires of employers opting to pay by the month is to assure that "the

monthly minimum wage shall not be less than the statutory minimum wage multiplied by 365 days

divided by twelve," and to pay that salary "for all days in the month whether worked or not," and

"irrespective of the number of working days therein." That salary is due and payable regardless of the

declaration of any special holiday in the entire country or a particular place therein, or any fortuitous

cause precluding work on any particular day or days (such as transportation strikes, riots, or typhoons or

other natural calamities), or cause not imputable to the worker. And as also earlier pointed out, the

legal provisions governing monthly compensation are evidently intended precisely to avoid re-

computations and alterations in salary on account of the contingencies just mentioned, which, by the

way, are routinely made between employer and employees when the wages are paid on daily basis.

Decision: In promulgating the orders complained of the public respondents have attempted to legislate,

or interpret legal provisions in such a manner as to create obligations where none are intended. They

have acted without authority, or at the very least, with grave abuse of their discretion. Their acts must

be nullified and set aside.

WHEREFORE, the orders complained of, namely: that of the respondent Undersecretary dated

September 22, 1993, and that of the Regional Director dated July 30, 1992, are NULLIFIED AND SET

ASIDE, and the proceeding against petitioner DISMISSED. SO ORDERED.

San Miguel Corporation vs. Court of Appeal January 30, 2002 375 SCRA 311 GR. No. 146775

FACTS: It was October 17, 1992, the Department of Labor and Employment, Illiigan district office,

conducted a routine inspection in San Miguel Corporation in Illigan city. DOLE discovered that there was

an underpayment by SMC of regular Muslim holiday pay to its employees. SMC contested the findings

and DOLE conducted summary hearings. SMC failed to submit proof that it was paying regular Muslim

holiday pay to its employees. DOLE issued a compliance order to consider Muslim holidays as regular

holidays and to pay both its Muslim and non-Muslim employees a holiday pay within 30 days from the

receipt of the order. SMC appealed to the DOLE main office in Manila, but its appeal was dismissed for

lack of merit. SMC, then, went to the Court of Appeals for a relief via a petition for certiorari.

Issue: Whether or not there is a distinction between Muslims and non-Muslims as regards to the

payment of benefits for Muslim holidays.

HELD: Muslim holidays are legally observed within the area of jurisdiction of the ARMM. It is only upon

presidential proclamations that Muslim holidays may be officially observed outside the ARMM and

generally extends to Muslims to enable them to observe the said holidays. There must be no distinction

between Muslims and non-Muslims as regards payment of benefits for Muslim holidays; wages and

other emoluments are laid down by law and not based on faith or religion.

MAKATI HABERDASHERY, INC., vs. NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION G.R. Nos. 83380-81

November 15, 1989

FACTS: Individual complainants have been working for petitioner Makati Haberdashery, Inc. as tailors,

seamstress, sewers, basters (manlililip) and "plantsadoras". They are paid on a piece-rate basis except

Maria Angeles and Leonila Serafina who are paid on a monthly basis. In addition to their piece-rate, they

are given a daily allowance of three (P 3.00) pesos provided they report for work before 9:30 a.m.

everyday. Private respondents are required to work from or before 9:30 a.m. up to 6:00 or 7:00 p.m.

from Monday to Saturday and during peak periods even on Sundays and holidays.

The Sandigan ng Manggagawang Pilipino, a labor organization of the respondent workers, filed a

complaint for (a) underpayment of the basic wage; (b) underpayment of living allowance; (c) non-

payment of overtime work; (d) non-payment of holiday pay; (e) non-payment of service incentive pay;

(f) 13th month pay; and (g) benefits provided for under Wage Orders Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Labor Arbiter rendered judgment in favor of complainants. The NLRC affirmed the arbiters decision.

Petitioner urged that the NLRC erred in concluding that an employer-employee relationship existed

between petitioner and the workers.

ISSUE: Whether employees paid on piece-rate basis are entitled to service incentive pay.

RULING: The facts at bar indubitably reveal that the most important requisite of control is present. As

gleaned from the operations of petitioner, when a customer enters into a contract with the

haberdashery or its proprietor, the latter directs an employee who may be a tailor, pattern maker,

sewer or "plantsadora" to take the customer's measurements, and to sew the pants, coat or shirt as

specified by the customer. Supervision is actively manifested in all these aspects the manner and

quality of cutting, sewing and ironing.

Petitioner has reserved the right to control its employees not only as to the result but also the means

and methods by which the same are to be accomplished. That private respondents are regular

employees is further proven by the fact that they have to report for work regularly from 9:30 a.m. to

6:00 or 7:00 p.m. and are paid an additional allowance of P 3.00 daily if they report for work before 9:30

a.m. and which is forfeited when they arrive at or after 9:30 a.m.

The workers did not exercise independence in their own methods, but on the contrary were subject to

the control of petitioners from the beginning of their tasks to their completion. Unlike independent

contractors who generally rely on their own resources, the equipment, tools, accessories, and

paraphernalia used by private respondents are supplied and owned by petitioners. Private respondents

are totally dependent on petitioners in all these aspects. The piece-rate workers in the case at bar are

employees which fall under exceptions set forth in the implementing rules and therefore not entitled to

service incentive leave and holiday pay.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Statutory Construction NotesDokument32 SeitenStatutory Construction Notespriam gabriel d salidaga95% (102)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Labor Law-San BedaDokument70 SeitenLabor Law-San BedaIrene Pacao100% (8)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Chapter 5: Newton's Laws of Motion.Dokument26 SeitenChapter 5: Newton's Laws of Motion.Sadiel Perez100% (2)

- Current Status Older PersonsDokument99 SeitenCurrent Status Older Personstweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Population LivingArrangementsDokument34 SeitenPopulation LivingArrangementsHetty ParsramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revised IRR of National Building Code - Why Is An Injunction NecessaryDokument56 SeitenRevised IRR of National Building Code - Why Is An Injunction NecessaryalainmelcresciniNoch keine Bewertungen

- DigestDokument14 SeitenDigesttweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- SJS v. Atienza, GR No.156052, February 13, 2008Dokument78 SeitenSJS v. Atienza, GR No.156052, February 13, 2008Jonna Maye Loras CanindoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department Order No. 19-93, April 1, 1993Dokument0 SeitenDepartment Order No. 19-93, April 1, 1993John SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sentinel v. NLRCDokument6 SeitenSentinel v. NLRCtweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- SC Rules Forest Land Patent Null Due to FraudDokument6 SeitenSC Rules Forest Land Patent Null Due to Fraudtweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- GMMSWMC v. Jancom, GR No. 163663, June 30, 2006Dokument24 SeitenGMMSWMC v. Jancom, GR No. 163663, June 30, 2006Jonna Maye Loras CanindoNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V. GenosaDokument16 SeitenPeople V. Genosatweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yabut and National Labor Relations Commission."Dokument7 SeitenYabut and National Labor Relations Commission."tweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Constitutions - Official Gazette of The Republic of The PhilippinesDokument2 SeitenPhilippine Constitutions - Official Gazette of The Republic of The Philippinestweezy240% (1)

- Policy Instructions No. 20-76Dokument3 SeitenPolicy Instructions No. 20-76tweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Omnibus Rules Book VIDokument3 SeitenOmnibus Rules Book VItweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dap & PdafDokument4 SeitenDap & Pdaftweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bengson v. HretDokument4 SeitenBengson v. Hrettweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Santos V. CADokument7 SeitenSantos V. CAtweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Macalintal v. ComelecDokument17 SeitenMacalintal v. Comelectweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law ReviewerDokument266 SeitenCriminal Law ReviewerivanlouieNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write A Case DigestDokument3 SeitenHow To Write A Case DigestJohari Valiao AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- UST GN 2011 - Criminal Law ProperDokument262 SeitenUST GN 2011 - Criminal Law ProperGhost100% (9)

- Natural LawDokument10 SeitenNatural Lawtweezy24100% (1)

- Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie by Bob DylanDokument3 SeitenLast Thoughts on Woody Guthrie by Bob Dylantweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hart NLDokument3 SeitenHart NLtweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nitto v. NLRCDokument4 SeitenNitto v. NLRCtweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Political Law Review University of The PhilDokument55 SeitenPolitical Law Review University of The PhilLorenz Angelo Mercader Panotes100% (1)

- H1Dokument7 SeitenH1tweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- H.L.A. HartDokument1 SeiteH.L.A. Harttweezy24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Master Circular on Baroda Mortgage Loan updated upto 30.09.2016Dokument41 SeitenMaster Circular on Baroda Mortgage Loan updated upto 30.09.2016RAJANoch keine Bewertungen

- Manage Your Risk With ThreatModeler OWASPDokument39 SeitenManage Your Risk With ThreatModeler OWASPIvan Dario Sanchez Moreno100% (1)

- SENSE AND SENSIBILITY ANALYSIS - OdtDokument6 SeitenSENSE AND SENSIBILITY ANALYSIS - OdtannisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Emergency's Impact on Press FreedomDokument13 SeitenNational Emergency's Impact on Press FreedomDisha BasnetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court of India Yearly Digest 2015 (692 Judgments) - Indian Law DatabaseDokument15 SeitenSupreme Court of India Yearly Digest 2015 (692 Judgments) - Indian Law DatabaseAnushree KapadiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mormugao Port (Adoptation of Rules) Regulations, 1964Dokument2 SeitenMormugao Port (Adoptation of Rules) Regulations, 1964Latest Laws TeamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ejercito V. Sandiganbayan G.R. No. 157294-95Dokument4 SeitenEjercito V. Sandiganbayan G.R. No. 157294-95Sabel FordNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aster Pharmacy: Earnings DeductionsDokument1 SeiteAster Pharmacy: Earnings DeductionsRyalapeta Venu YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neil Keenan History and Events TimelineDokument120 SeitenNeil Keenan History and Events TimelineEric El BarbudoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daniel 6:1-10 - LIARS, LAWS & LIONSDokument7 SeitenDaniel 6:1-10 - LIARS, LAWS & LIONSCalvary Tengah Bible-Presbyterian ChurchNoch keine Bewertungen

- PARAMUS ROAD BRIDGE DECK REPLACEMENT PROJECT SPECIFICATIONSDokument156 SeitenPARAMUS ROAD BRIDGE DECK REPLACEMENT PROJECT SPECIFICATIONSMuhammad irfan javaidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ordinance IntroducedDokument3 SeitenOrdinance IntroducedAlisa HNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life of St. Dominic de GuzmanDokument36 SeitenLife of St. Dominic de Guzman.....Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bolivia. Manual de Operacion de La Fabrica de Acido Sulfurico de EucaliptusDokument70 SeitenBolivia. Manual de Operacion de La Fabrica de Acido Sulfurico de EucaliptusJorge Daniel Cespedes RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sales Order Form 2019Dokument1 SeiteSales Order Form 2019Muhammad IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDokument4 SeitenStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceSiraj PNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2020.11.30-Notice of 14th Annual General Meeting-MDLDokument13 Seiten2020.11.30-Notice of 14th Annual General Meeting-MDLMegha NandiwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Description of The Prophet's Fast - Ahlut-Tawhid PublicationsDokument22 SeitenThe Description of The Prophet's Fast - Ahlut-Tawhid PublicationsAuthenticTauheed PublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Some Like The New Jim Crow So Much - A Critique (4!30!12)Dokument14 SeitenWhy Some Like The New Jim Crow So Much - A Critique (4!30!12)peerlesspalmer100% (1)

- SC Rules Civil Case for Nullity Not a Prejudicial Question to Bigamy CaseDokument3 SeitenSC Rules Civil Case for Nullity Not a Prejudicial Question to Bigamy CaseHazel Grace AbenesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Akun-Akun Queen ToysDokument4 SeitenAkun-Akun Queen ToysAnggita Kharisma MaharaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- AACC and Proactive Outreach Manager Integration - 03.04 - October 2020Dokument59 SeitenAACC and Proactive Outreach Manager Integration - 03.04 - October 2020Michael ANoch keine Bewertungen

- 0452 w16 Ms 13Dokument10 Seiten0452 w16 Ms 13cheah_chinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law Ii Notes: Non-Fatal Offences Affecting Human BodyDokument43 SeitenCriminal Law Ii Notes: Non-Fatal Offences Affecting Human BodyWai LingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Web Smart Des121028pDokument85 SeitenWeb Smart Des121028pandrewNoch keine Bewertungen

- DH - DSS Professional V8.1.1 Fix Pack - Release NotesDokument5 SeitenDH - DSS Professional V8.1.1 Fix Pack - Release NotesGolovatic VasileNoch keine Bewertungen

- ИБП ZXDU68 B301 (V5.0R02M12)Dokument32 SeitenИБП ZXDU68 B301 (V5.0R02M12)Инга ТурчановаNoch keine Bewertungen

- Niva Bupa Health Insurance Company LimitedDokument1 SeiteNiva Bupa Health Insurance Company LimitedSujanNoch keine Bewertungen

- IC33 - 8 Practice TestsDokument128 SeitenIC33 - 8 Practice TestskujtyNoch keine Bewertungen