Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Development of Tourism in Dubai Grace Chang Mazza

Hochgeladen von

Mohit Arora0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

155 Ansichten24 SeitenDubai Tourisam

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenDubai Tourisam

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

155 Ansichten24 SeitenDevelopment of Tourism in Dubai Grace Chang Mazza

Hochgeladen von

Mohit AroraDubai Tourisam

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 24

1

Development of Tourism in Dubai

HIS 640

Consumption Culture in the Middle East

Grace Chang Mazza

2

Introduction:

The World Tourism Organization (WTO), a United Nations agency, estimated that by the

end of 2012, one billion international tourists will have traveled the world. In 2011 international

tourism receipts surpassed $1 trillion

1

(UNWTO Tourism). However, the World Travel &

Tourism Council (WTTC) estimates that the direct economic impact of tourism to GDP is closer

to $2 trillion and the industry generated 98 million jobs worldwide. Furthermore, taking account

tourisms direct

2

, indirect

3

, and induced impacts

4

, the WTTC estimates that tourism contributed

over $6 trillion to global GDP (9% of total), 255 million jobs (1 in 12 jobs), and $743BN in

investments (5% of total) (Economic Impact).

Overview of Middle East Tourism Industry

Specifically in the Middle East

5

, overall growth in number of tourists for 2012 is

estimated to be -1%, which is up from a decline of 7% in 2011 due to the political turmoil and

instability in the region (International Tourism). The Middle East as a whole earned $46BN

from tourism receipts in 2011 (UNWTO Tourism). For the United Arab Emirates (UAE),

tourism directly contributed to around 6.5% of GDP in 2011, with total contributions, including

direct, indirect, and induced, accounting for 13.5% of GDP. From an employment standpoint,

tourism directly supported 166,000 jobs (4.6% of total employment) and its total contribution to

1

Unless otherwise noted, all currencies are reported in US dollars.

2

As defined by the WTTC, direct contribution to GDP is GDP generated by industries that deal directly with

tourists, including hotels, travel agents, airlines and other passenger transport services, as well as the activities of

restaurant and leisure industries that deal directly with tourists (WTTC).

3

As defined by the WTTC, indirect contribution to GCP is capital investment spending by all sectors involved in the

travel and tourism industry, general government spending in support of general tourism activity, and the purchases

of domestic goods and service by different sectors of the tourism industry as inputs into their outputs (WTTC).

4

As definted by the WTTC, induced contribution is the broader contribution to GDP and employment of spending

by those who are directly or indirectly employed by Travel & Tourism (WTTC).

5

The Middle East refers to: Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi

Arabia, Syria, UAE, and Yemen.

3

employment was 388,000 jobs (10.7%). The UAE invested almost $28BN in the travel and

tourism industry in 2011 and ranked ninth worldwide in terms of total capital invested tourism.

(WTTC)

Within the Middle East, the UAE accounted for

nearly 33% of travel and tourism demand most of that

is reflected in the number of visitors arriving in Dubai.

Dubai, in fact receives the largest number of visitors of

any Arab destination apart from Egypt. With notable

exceptions, the region remains relatively undeveloped

as a tourist destination, receiving only a fraction of

global tourist arrivals and global receipts. In 2011,

Dubai had an estimated 8MM tourist arrivals and

international receipts of $9.2BN (UNWTO

Tourism). As a whole, tourism in the UAE and

Dubai is dominated by tourists from the Middle East

and about 75% of tourists travel for leisure, while the

remainder travel for business (see charts at right).

Leisure travelers are heavily skewed towards Dubai as

the rest of the UAE is underdeveloped when it comes

to tourism. Outside of Dubai, tourism in the Middle East is not associated with leisure or

vacation travel and tends to be dominated by business or religious travel, specifically with regard

to Saudi Arabia. In most of the Middle East, international leisure tourism is either culturally

Middle

East

42%

Europe

26%

Asia

9%

USA

3%

Other

20%

UAE 2011 Arrivals by

Origin

Business

24%

Leisure

76%

UAE 2011 Arrivals by

Purpose of Visit

Source: Euromonitor 2012

Source: Euromonitor 2012

4

undesirable or economically unnecessary because of large oil reserves (Sharpley 2008).

Moreover, political instability in various countries also presents a barrier to tourism development.

The UAE, and Dubai in particular, have been exceptions to other Middle Eastern

countries. The UAE put tourism at the core of its economic development plans in order to

diversify and strengthen its economy, while decreasing its dependency on fluctuating oil prices

(Sharpley 2008). The plans have been successful; in 2007, non-oil revenues contributed to 63%

of GDP, with Abu Dhabi and Dubai contributing 59% and 29%, respectively, to the UAEs total

GDP. What is more surprising is that due to Dubais push to use tourism to diversify its

economy, Dubai contributes over 80% of the non-oil related GDP in the UAE. Dubai is now

considered one of the top tourist destinations in the world. In 2011, Dubais top tourist source

markets outside the UAE were Saudi Arabia, India, UK, Iran, and the US (Guests). Ironically,

while tourism in the Middle East overall was negatively impacted by the Arab Spring, Dubai was

positively impacted in that tourists and business activities in other countries in the region were

diverted to Dubai (United Arab).

Source: Department of Tourism and Commerce Marketing

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

Dubai Hotel Guests by Nationality (MM's)

Europe Asia Other AGCC Country UAE Other Arab Americas Africa (ex. Arab) Australasia & the Pacific

5

Public Policy and Tourism

Based on tourisms impact on worldwide and regional GDP and employment, it is clear

that understanding how to plan for and develop the tourism industry can have many benefits and

should in fact be incorporated into a countrys public policy strategy. From a branding

perspective, the execution of destination branding has often been limited to the design and

development of logos (Balakrishnan 2008). A more encompassing strategy involving

implementation of public policies to facilitate trade and investment can produce far better results.

Balakrishnan discusses the importance of this strategy being focused, while still considering the

diversity of both internal and external stakeholder needs. Furthermore, in considering a

countrys tourism strategy, it is important to remember that destination loyalty (level of tourist

perceptions of a destination as a recommendable place) was significantly dependent on safety,

perceived cultural differences, and perceived convenience of transportation (Balakrishnan 2008).

As discussed later, Dubai serves as an example of how public policy can be used to successfully

shape the tourism industry.

Gastronomic Tourism

In developing a tourism strategy, it is important to remember the relationship between

food and tourism. Food is an important tourist attraction and can enhance or is central to the

visitor experience (Henderson 2009). Food is more than nourishment, it offers pleasure and

entertainment and serves a social purpose. It is also a key part of all cultures, a major element

of global intangible heritage and an increasingly important attraction for tourists (Richards

2012).

6

There is a wide range of ways that tourists interact with food. Those that are more

serious can participate in organized activities like sampling and learning about food. This

interest, often labeled as culinary tourism, gastronomy tourism, or tasting tourism, also

incorporates that appreciation of beverages, both of the alcohol and non-alcoholic nature. On the

other end of the spectrum are tourists with a casual attitude towards food; however, even these

people need to decide what and where to eat when they are traveling. In the middle are those

who enjoy dining out and trying local cuisine when traveling for leisure or business. Others

enjoy watching the scenes at local markets or sampling and purchasing produce linked to the

destination. A visitors gastronomic experiences at their destination can also change their

consumption patterns when they return home due to the exposure of previously unknown

ingredients and cooking methods. (Henderson 2009)

What visitors want out of their food experience varies. As visitors become more

adventurous, many are looking for something genuine and authentic, which they believe can be

found in local foods and eating areas. The presence of locals and sharing space with them can be

viewed as a facet of tourism and a sign of authenticity, while establishments dominated by

tourists are shunned. At the same time, there is a trend towards standardization and

homogenization; tourists wary of unfamiliar environments -- where both the food and people are

foreign, prefer to frequent establishments they are familiar with. This has been one of the drivers

in the spread of fast food chains. Dubai has also seen this with the influx of American mid-

priced chain restaurants entering the market. As the world becomes more globalized and

governments plan their tourism strategy, as with other areas, governments need to find a balance

between both local and global to appeal to tourists. (Henderson 2009)

7

Gastronomic experiences play a part in determining perceptions of and

satisfaction with the overall travel experience and food is agreed to

impinge on tourist attitudes, decisions and behavior. Food and wine can

be a very powerful influence on feelings of involvement and place

attachment and poor quality and service failure can impact negatively on

health, disrupting trips and tarnishing destination reputations (Henderson

2009).

Tourism in Dubai

Dubais History and Political-Economy

In the 1960s, the UAE could be described as barren coastlands largely populated by

nomadic tribes where the only occupations are fishing and pearling (Henderson 2006). Dubai

was one of the least developed countries in the world (Sharpley 2008).

Dubais then ruler, Sheikh Rashid Bin Saeed Al Maktoum, led the charge to transform

Dubai from a barren coastland into the dreamworld of conspicuous consumption it is today

(Sharpley 2008). In the 1980s, oil production accounted for 2/3 of the countrys GDP, with

tourism limited to business travel. Ironically, Richard Sharpley attributes Dubais success in

diversifying away its economic reliance on oil through tourism to it being a rentier state, that is,

a state in which economic development and fiscal policy are based upon the rent gained from

the exploitation of natural resources. A particular characteristic to the rentier state is that the

generation and distribution of this rent or wealth is controlled by an elite or ruling minority. The

table on the next page summarizes the characteristics of a rentier state. Richard Sharpley argues

8

that because of Dubais wealth from oil and also the authoritarian political structure, the emirate

was able to make and implement tourism and infrastructure policies that have a direct impact on

tourism in ways and achieve results that other countries with different political-economic

systems could not.

Source: Sharpley, 2008

9

Dubais Tourism Policies

In 1966, Dubai accidentally discovered oil; however, unlike Abu Dhabi, whose oil

reserves are estimated to be sufficient for 100 years, Dubais reserves are expected to last no

more than a decade. As the second largest state in the UAE and in an effort to diversify its

reliance on oil, Dubai emerged as a service hub with shipping, financial and commercial services,

media, and tourism. It was ideally suited to serve this role, because of its strategic geographic

location at the confluence of the Middle East, Asia, Western Africa, and Central/Eastern Europe

(Balakrishnan 2008). Because of its location, Dubais initial commercial expansion, the

development of the Jebel Ali port, the worlds largest man-made port, was funded by the UAE.

In the 1990s, tourism was identified as a viable economic development option and

Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum set a strategic vision for the emirate: tourism would

act as a catalyst for foreign direct investment and wider business development, rather than just

establishing a tourism industry. The emirate would market itself to business travelers in Western

Europe and neighboring Gulf countries. In order to be successful, this strategy was supported by

intense transport and infrastructure development, which included setting up the state-owned

Emirates Airlines and the Dubai Commerce and Tourism Protection Board (DCTPB), later

becoming the Department of Tourism and Commerce Marketing (DTCM). The early role of the

DCTPB was to be a government agency responsible for promoting activities of various

organizations involved in tourism, including Emirates Airlines. During the initial phase, there

was already a focus on high-end, luxury facilities. The development of hotels also fell under the

purview of the government and as early as 1985, 26 out of the 42 hotels in the emirate were

classified as deluxe/ first-class. This initial strategy of marketing itself to business travelers was

highly successful, and led to a shift in focus to developing an entirely new tourism industry

10

within the overall objective of developing Dubai as an international business and service hub as

defined by the 30-year development plan (Sharpley 2008). This new plan proposed three

phases of development:

Source: Sharpley, 2008

The first phase, lasting from 1996-2000, began with the creation of the DTCM to

establish a principal authority for the planning, supervision and development of tourism in the

emirate (Sharpley 2008). Unlike other developing countries, Dubai realized its lack of domestic

expertise and had the foresight to hire external consultants for long-term advisory positions,

rather than short term involvements. As part of their pro-tourism policies, the emirate enacted

liberal trade policies. They also allowed open skies transportation policies, allowing any

airline to fly through Dubai. In recognition of how the Middle Easts religious restrictions on

food and clothing could have a negative impact on its tourism and international economic

11

development, Dubai removed dress code and alcohol consumption restrictions, becoming one of

the more liberal states in the region.

The emirate, and more specifically, the royal family made significant investments in

facilities and attractions. During this period, the first seven-star hotel, the Burj Al Arab hotel

was built. It is owned by the royal family and was built as part of the state-owned Jumeirah

international hotel chain. Financial analysts doubt that this project will ever provide returns

acceptable to typical financial investors; however, from a tourism and public policy perspective

it can be considered a success as it is now an iconic landmark in Dubai and led the way for the

additional high-end luxury developments by international hotel chains (Sharpley 2008).

The government also recognized that given Dubais desert climate, tourism in its hot

summer months would always be less attractive unless certain attractions or events were

specifically developed to draw tourists to the emirate during the summer months. Because of

this, specific events were created with the intent to reduce industry seasonality. These events

included the Dubai Shopping Festival and Dubai Summer Surprise. The Summer Surprise is a

10-week shopping, child-focused extravaganza. It combines discounted hotel prices with

activities directed at families. Colorful cultural ceremonies such as Bedouin weddings often

form part of the festivities, as well as powerboat competitions, horse races and golf, tennis and

rugby tournaments with extremely generous prizes. (Henderson 2006)

In addition to government involvement, Dubai recognized that one of the key factors for

the success of Dubais tourism industry is the strategic partnership between the government and

the private sector (Sharpley 2008). Partnerships with local and international, although mostly

Middle Eastern investors, were encouraged in order to share the developmental costs of the

12

aforementioned projects and events. As a measurement of the success of these initiatives, many

of these events, although initially created and supported by the DTCM, eventually became fully

private-sector funded initiatives.

The second phase of the emirates development plan lasted from 2001-2010 and targeted

increasing annual tourist arrivals in 2010 to 15MM. The DTCM was primarily focused on

marketing and promotional activities and was supported by offices in 15 key overseas markets.

Its role was broadened to include managing the licensing of hotels, tour operators, tour guides,

and transport operators. The DTCMs goals for this phase also included the development of

sustainable tourism, encouraging public-private partnerships, quality management within the

tourism industry, and improving skills and employment opportunities. Dubai also recognized the

importance of culture in being a successful tourist destination and the DTCM began a policy of

cultural conservation during this period, which led to the development of various cultural events,

such as Bedouin wedding ceremonies during the Summer Surprise festivals. (Sharpley 2008)

The emirate continued with its pro-tourism policies by liberalizing visa and land

ownership restrictions. Dubais land ownership laws did not allow foreigners to own land;

however, restrictions were loosened such that foreign land ownership was allowed in certain

tourism development areas. Within these areas, such as the Internet and Media Cities, the Palms,

and the Dubai Marina, full foreign ownership of land was allowed, although this ownership was

still limited to 99-year leases. The government attempted to improve employment opportunities

for the local population; however, given that only 7% of the population over age 15 consists of

local emiratis and local emiratis had expectations of employment in white-collar, managerial

posts, rather than tourism, this area had limited success (Population).

13

Throughout this period, the supply of hotels and hotel rooms have doubled (see chart on

next page). The majority of this growth has been in the high-end, luxury segment of four- and

five-star hotels which have had an average annual growth rate of 16.5% and 10.2%, respectively.

As a function of hotel room availabilities and also alcohol sales restrictions, the majority of

visitors (65% of residence nights) stayed in high-end hotels and Dubai was able to attract some

of the highest hotel rates in the world.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

Dubai Hotel Rooms by Class ('000s)

Five-Star Four-Star Three-Star Two-Star One-Star Listed/ Guest House

5-Star

40%

4-Star

25%

3-Star

16%

2-Star

10%

1-Star

8%

Listed

1%

2011 Residence Nights by

Hotel Classification

Source: Dubai Statistics Center

Source: Department of Tourism and Commerce Marketing

14

In addition to hotels, there was continued attraction and infrastructure developments,

most notably of these was The Palm Islands, an offshore development of three manmade islands,

each of which will add 160km of shoreline to mitigate the saturation of Dubais existing

coastline. The concept of the Palms is that the development will accommodate new hotels,

residential villas, shoreline apartments, marinas, water parks, restaurants, shopping malls, sports

facilities, health spas, and movie theaters. Of the three islands, Palm Jumeirah, is slated to have

a $650MM, 2,000-room resort and water park that is being developed through a joint venture

between Nahkeel and Kerzner International. Construction on this island began in 2001 and is

almost complete, with the first residents arriving in 2006. The second island, Palm Jebel Ali,

began construction in October 2002, but was slowed by project delays due to the downturn in the

construction in 2008. Finally, work on the third and largest island, Palm Deira, began in

November 2004 (United Arab). Other public-private developments include The World, a

cluster of 250 manmade islands off the Jumeirah coastline between the Burj Al Arab and Port

Rashid. Each of these islands will be sold to private developers. Ski Dubai was successfully

opened in 2005 to combat seasonality by encouraging tourism during the low season with an

indoor ski slope.

Furthermore, the Dubai Metro project was started. The first part of the project consisted

of upgrading the existing Dubai International Airport and the second, beginning construction of

the new 6-runway World Central International Airport. The new airport is slated to be the

worlds largest airport handling 120MM passengers by 2025. Once again, in an effort to

encourage public-private partnership, the initial investment of the airport was provided by the

government, with the goal that the balance would be financed through private financing. Being a

rentier state, Dubai benefited enormously from the continuing inclination of the oil sheiks to

15

invest within, rather than outside, the region, as profits from regional oil producing countries

were invested in Dubais tourist-friendly infrastructure program (Sharpley 2008). For example,

in 2004, Saudi Arabian investors invested $7BN into major property developments in Dubai.

One of the key reasons of success can be attributed to the regional oil profits, as most of the

capital used to finance these policies were derived from oil production.

Not all investments were a success, in 2009, due to oversupply and weak investor

confidence, the state-owned investment company, Dubai World, met with creditors to discuss

delaying the repayment of their $25BN debt. The issues were resolved in September 2010 when

99% of its creditors agreed to restructure the $25BN liabilities. As part of the agreement, Dubai

World was forced to, over the next eight years, sell a number of their prized assets, which are

valued at around $18BN. Also in 2010, Dubai Holding reached an agreement with its creditors

to extend the repayment of its $555MM credit facility. The development of Dubailand, the

biggest terrestrial tourism development, began in 2003, however further development was put on

hold in 2008 due to the global recession and economic crisis. It was to have been the most

ambitious leisure complex, attracting an estimated 200,000 visitors per day and housing the

largest shopping complex in the world and a Snowdome.

Keys to Success

Despite the setbacks that have been primarily caused by the global economic crisis and

economic recession in 2008, Dubai is a successful example of developing a Middle East tourism

center. The factors that have led to this success have been its political stability, government

policies, and geographic accessibility.

16

Unlike other countries in the region, Dubai has experienced a relatively extended and

uninterrupted period of political order, along with economic prosperity.

Dubai acts as a regional entrepot and promotes itself as the commercial

and financial nexus of the Gulf, energetically creating free-trade zones and

industrial parks such as the latest ones devoted to the Internet and

Media. is seen as a comparatively liberal and cosmopolitan society, with

little threat of civil unrest and low crime rates, and expatriates make up

about 80% of the 1.2 million population (Henderson 2006).

As demonstrated above, the Dubai government has taken an extremely active role in the

development of tourism through legislation and investment in infrastructure, with the rulers of

Dubai setting the vision that Dubai will be a leading tourism destination and commercial hub in

the world (Henderson 2006). Tourism was viewed as a way to diversify its economy away

from its reliance on oil profits. Hospitality development has been facilitated by a relaxation of

land ownership laws. Public-private partnerships have launched events to reduce seasonality.

From an accessibility standpoint, Dubai aspires to be an air transport hub for the Middle

East and Far East and would like to also be considered a cruising hub and destination, similar to

Singapore. In order to achieve this goal, the government has simplified visa procedures to

streamline the passenger processing. (Henderson 2006)

Challenges and Opportunities

As Dubai enters the third phase of its tourism strategic plan, it clearly has succeeded

because of the significant financial resources it and its neighboring countries possess, as well as

17

its ability to control and manage development in a way that democratic, market-led economies

would not be able to. However, there are a number of areas where it can improve.

Currently, the DTCM has been tasked with marketing and promotional offices to support

the tourism initiative. The problem with the DTCM is its lack of authority. It neither has

exclusive authority nor the mechanisms for managing the sector (Sharpley 2008). In Dubai, this

power belongs to the Dubai Executive Council, a government body made up of chairmen/CEOs

of public, private, and quasi-government organizations, major government owned development

companies, and government departments involved in tourism planning and management. The

DTCM is neither recognized nor able to act as the official tourism data collection and

dissemination source in Dubai, as a result tourism related data is spread through this organization,

the Dubai Statistics Center, and the Dubai Chamber of Commerce, among other agencies. No

tourism development project is allowed to proceed without the approval of the rule and even

though the Sheikh is the head of the DTCM, it is frequently excluded from the overall tourism

planning and strategizing process, as those usually occur behind closed doors at the Dubai

Executive Council. (Sharpley 2008)

The role of the DTCM has become one where it encourages investment and then

promotes the resulting product, rather than take an active stand in shaping the development of

and investment in the tourism project. Furthermore, because all decisions must be channeled

through the Sheikh, there tends to be a lack of central authority and rigor in approving project

developments. Sharpley provides the example of how investment proposals for the development

of hotels must be approved by the Sheikh, once the approval is received the actual design, scale,

and nature of the hotels is left to the development companies, without any central oversight. In

2005, this mismatch, or even lack of, oversight resulted in a shortage of rooms, causing a 35%

18

price increase. It is clear that the mismatch still exists as the average annual growth rates for

tourist arrivals for 2002-2011 was 7.5%, but for the same period hotel rooms grew at a rate of

close to 10%.

There are concerns about the amount of capital spending the government is putting into

an unpredictable and cyclical industry and that tourism is responsible for unprecedented

construction and a potential real estate bubble. The figure below shows the magnitude of

development between 1990 and 2005. Furthermore, Dubai must face the environmental impact

of its development in a region that already has natural resource limitations.

While Dubai has already taken many steps to make itself friendlier to foreign investors, it

could do more in the way of its land ownership rules to further increase development. Currently

Source: Balakrishnan 2008

19

land and real ownership laws require a local business or organization have a least 51%

ownership. Certain free zones, such as Internet City and Media City are not subject to these

laws, because international businesses operate under regulatory and legal bubble-domes tailored

to the specific needs of foreign capital (Sharpley 2008). As a result, all hotel developments are

still locally owned, but usually managed by international or local hotel chains.

Moreover, Dubai has developed a reputation of being expensive and does not enjoy a

high level of repeat tourism, as shown in the chart below, average stays are relatively short, with

an average across visitors of 3.2 nights, because it still relies on the short-stay/stop-over market.

Most of its attractions focus on individuals and feature a theme of a conspicuous consumption

lifestyle. In marketing materials, Dubai is positioned as the home of luxury brands. For example,

the average daily private consumption spending in Dubai is $26.80 versus $3.80 in the rest of the

Arab world. Visitors spend over $700MM annually at Dubai Duty Free, third only to Heathrow

and Incheon. As a result of the various shopping festivals that Dubai has organized and

Ramadan initiatives, nearly 2/3 of the annual gold and jewelry sales occurs around these select

2.3

2.8

3.1

3.0

4.2

2.7

2.4

3.2

UAE Other

AGCC

Other

Arab

Asia and

Africa

Europe Americas Oceana Overall

Average Length of Stay by Nationality

Source: Dubai Statistics Center

20

activities. Visitors to Dubai are coming more for shopping than for leisure or business activities.

While this currently benefits the emirate, the preoccupation with luxury and consumerism could

lead to the neglect of tourists with more modest budgets, whose spending is just as valuable.

(Balakrishnan 2008; Henderson 2006)

Compared with competitive destinations such as the Caribbean, Mediterranean, and

South East Asia, Dubai has a more narrow selection of cultural and natural heritage attractions

(Henderson 2006). Certain existing and planned leisure facilities such as shopping complexes

and theme parks have a sterility and homogeneity, which tourists may tire of once novelty wears

off (Henderson 2006).

Gastronomic Tourism in Dubai

One of the ways Dubai can try to increase visitor loyalty, increase their length of stays,

and appeal to more middle-class visitors and increase its cultural appeal is potentially through

gastronomic tourism. As stated by Henderson, food and wine can be a very powerful influence

on feelings of involvement and place attachment (2009). Dubai is emerging as of the up and

coming gastronomic destinations. In a recent survey 2/3 of UAE residents admit to eating out at

least twice a week and choosing food quality over price (Slow Economy).

Because of the large percentages of expatriates working Dubai, the multicultural

population has created demand for food from everywhere and has helped launch a restaurant

scene that is receiving accolades from chefs and tourists (Gastronomic). Its reputation as a

gastronomic destination has grown to the point where it is attracting attention from

internationally renowned chefs, several of whom have opened up restaurants in Dubai. The first

21

such international chef was Gordon Ramsay, who opened Verre in 2001 at the Hilton Dubai

Creek. Gary Rhodes then opened Rhodes Mezzanine in the Grosvenor House in 2007 and Nobu

Matsuhisa followed with Nobu Atlantis in 2008.

Because of alcohol restrictions, only four- and five-star hotel properties are permitted to

sell alcohol, so most of these high-end gastronomic restaurants are located within these hotels.

Dubai already has a culture of indulging in food with opulent Friday brunches a popular activity

for both locals and visitors. For example, at the Fairmont Dubai, diners can choose between 200

signature dished with unlimited Mot & Chandon champagne (Gastronomic).

Dubai has developed a number of events to promote its food culture. In 2007, the

Jumeirah Hotel Group, in conjunction with American Express and several other regional partners

launched a Festival of Taste. The five-day festival brought together high-profile chefs and was

later transformed into the Taste of Dubai. The Taste of Dubai features a variety of gastronomic

events during which visitors can sample signature dishes from Dubais leading restaurants and

watching cooking demonstrations, while being entertained by some of the regions favorite and

new musical bands. More recently, the Emirates Culinary Guild (ECG) was founded as a

professional association, whose mandate is the promotion of culinary arts of the UAE. ECG also

publishes a trade magazine and is involved in the Emirates International Salon Culinaire. This

prestigious international competition draws hundreds of chefs who are judged by a panel of

culinary experts approved by the World Association of Chefs Societies (WACS)

(Gastronomic).

22

Conclusion

Dubai is often referred to as Dubai, Inc., because everything in the emirate is largely

owned by the royal family or through government owned organizations. In an effort to diversify

its economic reliance on oil, Dubai wanted to become the center of international business and

services in the Middle East. One of the ways it has achieved this is through its public policy

towards tourism. Dubais actions towards and success around tourism are a direct result of its

and its neighbors wealth from oil, as well as its central planning. While it has achieved

remarkable success in a relatively short period, its tourism industry and overall development has

also been affected by the global financial crisis and Arab Spring movements. As Dubai resets its

course after its own economic recession, it needs to be aware of opportunities within the tourism

industry around focusing on consumer segments other than the high-end, luxury tourists and

developing cultural and heritage attractions, potentially around the booming gastronomic tourism

market and its emergence as a gastronomic destination.

23

Bibliography

Balankrishnan, Melodena Stephens, Dubai a Star in the East: A Case Study in Strategic

Destination Branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, Vol. 1 No.1

(2008): 62-91.

Dubai Total Hotel Establishment Guests by Nationality. Department of Tourism and

Commerce Marketing, accessed December 11, 2012,

http://www.dubaitourism.ae/sites/default/files/hotelstat/2002-

2011_Dubai_Hotel_Establishment_Guests_by_Nationality.pdf.

Economic Impact of Travel & Tourism 2012: Summary. World Travel & Tourism Council,

accessed December 11, 2012,

http://wttc.org/site_media/uploads/downloads/Economic_impact_reports_Summary_v3.p

df.

Gastronomic Tourism International May 2009. Mintel Reports Database.

Guests and Residence Nights at Hotels by Nationality and Classification Category Emirate of

Dubai. Dubai Statistic Center, accessed December 12, 2012,

http://dsc.gov.ae/Reports/DSC_SYB_2011_12_11.pdf.

Henderson, Joan C., Food Tourism Reviewed. British Food Journal, Vol. 111 Iss. 4 (2009):

317-326.

Henderson, Joan C., Tourism in Dubai: Overcoming Barriers to Destination Development.

International Journal of Tourism Research, 8 (2006): 87-99.

International Tourism Strong Despite Uncertain Economy. World Tourism Organization,

accessed December 11, 2012, http://www2.unwto.org/en/press-release/2012-11-

05/international-tourism-strong-despite-uncertain-economy.

Number of Dubai Hotels & Available Rooms By Class. Department of Tourism and

Commerce Marketing, accessed December 11, 2012,

http://www.dubaitourism.ae/sites/default/files/hotelstat/2002-

2011_Dubai_Hotels_&_Rooms_by_Class.pdf.

Population (15 Years and Over) by Nationality, Sex and Economic Activity Status Emirate of

Dubai. Dubai Statistics Center, accessed December 12, 2012,

http://dsc.gov.ae/Reports/DSC_LFS_2011_01_01.pdf.

Richards, Greg, An Overview of Food Tourism Trends and Policies. in Food and the Tourism

Experience: The OECD-Korea Workshop. OECD Studies in Tourism: OECD Publishing,

2012

24

Sharpley, Richard, Planning for Tourism: the Case of Dubai. Tourism and Hospitality

Planning and Development, Vol. 5 Iss. 1 (2008): 13-30.

Slow Economy Doesnt Eat into UAE Dining Habits, Arabian Business.com, accessed

December 11, 2012, http://www.arabianbusiness.com/slow-economy-doesn-t-eat-into-

uae-dining-habits-416810.html

Tourism Flows Inbound in the United Arab Emirates. May 2008, Global Market Information

Database. Euromonitor International.

United Arab Emirates Tourism Report Q4 2012. October 2012. Business Monitor

International.

UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2012 edition. World Tourism Organization, accessed December

11, 2012,

http://dtxtq4w60xqpw.cloudfront.net/sites/all/files/docpdf/unwtohighlights12enlr_1.pdf.

WTTC, Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2012 United Arab Emirates, World Travel &

Tourism Council, accessed December 11, 2012,

http://wttc.org/site_media/uploads/downloads/united_arab_emirates2012.pdf.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Feasibility Report Amusement Park NRDADokument28 SeitenFeasibility Report Amusement Park NRDANityaMurthy89% (9)

- Analysis of ICT Usage PatternsDokument16 SeitenAnalysis of ICT Usage PatternsFajri FebrianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tourism in U.A.EDokument30 SeitenTourism in U.A.EalzinatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lisbona TLx14 Marketing Plan 2011 2014Dokument52 SeitenLisbona TLx14 Marketing Plan 2011 2014Davide Conflitti100% (1)

- Project WBS ChartDokument4 SeitenProject WBS ChartMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Culture and Tourism Geography ReviewerDokument12 SeitenPhilippine Culture and Tourism Geography ReviewerRoselyn Acbang100% (2)

- OS at Gateway VarkalaDokument64 SeitenOS at Gateway VarkalaSyam RajuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tourism Industry Profile IndiaDokument23 SeitenTourism Industry Profile IndiaPrince Satish Reddy50% (2)

- AI in Travel and Hospitality Market - Global Industry Analysis, Size, Share, Growth, Trends, and Forecast - Facts and TrendsDokument3 SeitenAI in Travel and Hospitality Market - Global Industry Analysis, Size, Share, Growth, Trends, and Forecast - Facts and Trendssurendra choudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Events (Mice) TH5KH950: UWL STUDENT ID-21392272 TURNITIN - 92815172 WORDCOUNT - 1751Dokument6 SeitenCorporate Events (Mice) TH5KH950: UWL STUDENT ID-21392272 TURNITIN - 92815172 WORDCOUNT - 1751SHUBRANSHU SEKHAR100% (1)

- BTTM 704 Outbound TourismDokument66 SeitenBTTM 704 Outbound TourismSaurabh ShahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Lifestyles in The United Arab EmiratesDokument65 SeitenConsumer Lifestyles in The United Arab Emiratesu76ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tourism Marketing: Diana Jacob Viren Shah Kapil Athwani Priyanka Abhyankar Isha KolabkarDokument26 SeitenTourism Marketing: Diana Jacob Viren Shah Kapil Athwani Priyanka Abhyankar Isha KolabkarreetsdoshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- INDIA - UAE Trade RelationDokument20 SeitenINDIA - UAE Trade RelationAditya LodhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Overview of Indian Tourism IndustryDokument21 SeitenAn Overview of Indian Tourism Industrynishtichka100% (3)

- The Market 2008Dokument108 SeitenThe Market 2008rakeshkrNoch keine Bewertungen

- COuntry COmparisonDokument8 SeitenCOuntry COmparisonDevan GoyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Booking Holdings Inc.: Submitted byDokument58 SeitenBooking Holdings Inc.: Submitted byNancy JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- UAE Confectionery Sales Rise 11% in 2010Dokument2 SeitenUAE Confectionery Sales Rise 11% in 2010Moayad El Leithy0% (1)

- Airline and Travel Industry IntroductionDokument7 SeitenAirline and Travel Industry IntroductionMahender SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dubai BankDokument43 SeitenDubai BankArslanMehmoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rise of Medical Tourism SummaryDokument12 SeitenRise of Medical Tourism SummaryJack RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- UAE PESTLE ANALYSISDokument13 SeitenUAE PESTLE ANALYSISrishifiib08100% (1)

- Sustainability in TourismDokument10 SeitenSustainability in TourismNoeen FatmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Students Are Requested To Remit The Fee For SAP Dubai As Per The Following DetailsDokument12 SeitenThe Students Are Requested To Remit The Fee For SAP Dubai As Per The Following DetailsAchin AgarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gul Ahmed Business Plan For DubaiDokument25 SeitenGul Ahmed Business Plan For DubaiZain ImranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study Id65436 International Tourism in IndiaDokument62 SeitenStudy Id65436 International Tourism in Indiakausthubh vitthalNoch keine Bewertungen

- ITB World Travel Trends Report 2010/2011Dokument30 SeitenITB World Travel Trends Report 2010/2011Pablo AlarcónNoch keine Bewertungen

- C Marketing PlanDokument15 SeitenC Marketing PlanHồ AnhNoch keine Bewertungen

- HT Muslim Millennial Travel Report 2017Dokument46 SeitenHT Muslim Millennial Travel Report 2017Najma Qolby JuharsyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- BC - Projects Portfolio Overview - Oct - LR1 Austrialia Hotel GroupDokument39 SeitenBC - Projects Portfolio Overview - Oct - LR1 Austrialia Hotel GroupEshwar KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service Industry ManagerDokument16 SeitenService Industry ManagerNoora Al Shehhi100% (1)

- Gulf Projects Market OutlookDokument20 SeitenGulf Projects Market Outlookmohamad5357Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tourism 2023 Full Report Web VersionDokument57 SeitenTourism 2023 Full Report Web VersionSam KimminsNoch keine Bewertungen

- PESTEL Analysis On Bahrain Economic FounDokument13 SeitenPESTEL Analysis On Bahrain Economic FounMohamed ChebaichebNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Travellers' Perspective On Factors AffectingDokument17 SeitenMedical Travellers' Perspective On Factors AffectingBisma HarjunoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mgt372 International Hotel ProjectDokument23 SeitenMgt372 International Hotel ProjectPalash Debnath100% (1)

- Customs Procedure 20080701Dokument11 SeitenCustoms Procedure 20080701Anonymous 1gbsuaafddNoch keine Bewertungen

- China Hotel IndustryDokument10 SeitenChina Hotel IndustryProf PaulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Updated Tryvium WhitepaperDokument51 SeitenUpdated Tryvium WhitepaperTryviumNoch keine Bewertungen

- GCC Customers TravelDokument37 SeitenGCC Customers TravelCeyttyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hospitality Business Middle East, June 2013Dokument60 SeitenHospitality Business Middle East, June 2013Louie AlmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Are Investors Absolutely Necessary For Startups SurvivalDokument11 SeitenAre Investors Absolutely Necessary For Startups SurvivalTrue046Noch keine Bewertungen

- 9 - Promotion Strategy Anu KavitaDokument3 Seiten9 - Promotion Strategy Anu KavitaRamandeep KaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study MOS Dubai-Destination BrandingDokument12 SeitenCase Study MOS Dubai-Destination Brandingarunangshu_pal100% (1)

- Arabian Travel Market 2022Dokument10 SeitenArabian Travel Market 2022India OutboundNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Tourism in India: A Case Study of Apollo HospitalsDokument11 SeitenMedical Tourism in India: A Case Study of Apollo HospitalsBabu George88% (8)

- Shaping The Future of Travel in Asia PacificDokument32 SeitenShaping The Future of Travel in Asia PacificskiftnewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mice Assessment - 1 Module Leader-Bitan BoseDokument9 SeitenMice Assessment - 1 Module Leader-Bitan BoseSHUBRANSHU SEKHARNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tourism Management System Project ReportDokument76 SeitenTourism Management System Project ReportPawan VermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GCC Food Industry Report 2015Dokument112 SeitenGCC Food Industry Report 2015Hesham TabarNoch keine Bewertungen

- UntitledDokument52 SeitenUntitledapi-161235517Noch keine Bewertungen

- Global Vision Travel, Company Profile JordanDokument9 SeitenGlobal Vision Travel, Company Profile JordanTawfiq Issa100% (7)

- Conference Tourism in KenyaDokument7 SeitenConference Tourism in KenyaFriti FritiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment Help DubaiDokument2 SeitenAssignment Help DubaiAssignment Help DubaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1.1 The Tourism Industry OverviewDokument14 SeitenModule 1.1 The Tourism Industry OverviewGretchen LaurenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abu Dhabi Toursim DocumentsDokument25 SeitenAbu Dhabi Toursim DocumentsAdventure EmiratesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faisal Zaid I ThesisDokument78 SeitenFaisal Zaid I Thesisfzaidi14Noch keine Bewertungen

- KPMG The Indian Golf Market 2011Dokument3 SeitenKPMG The Indian Golf Market 2011manishthakur08100% (1)

- Factor Affecting The Tour Package FormulationDokument9 SeitenFactor Affecting The Tour Package Formulationmadhu anvekarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tourist Guide DubaiDokument32 SeitenTourist Guide DubaiPradyumna PathakNoch keine Bewertungen

- OECD Tourism Innovation GrowthDokument150 SeitenOECD Tourism Innovation GrowthInês Rodrigues100% (1)

- Commercial management Complete Self-Assessment GuideVon EverandCommercial management Complete Self-Assessment GuideNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sink or Shine: Attract Clients and Talent With the Brightness of Your MissionVon EverandSink or Shine: Attract Clients and Talent With the Brightness of Your MissionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Central Excise GuideDokument9 SeitenCentral Excise GuideMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- OD429179211415106100Dokument1 SeiteOD429179211415106100Mohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- HMEL Production Schedule BathindaDokument1 SeiteHMEL Production Schedule BathindaMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Incoterms Shipping GuideDokument60 SeitenIncoterms Shipping GuidejumbotronNoch keine Bewertungen

- MEM No - 010 Rev-1Dokument30 SeitenMEM No - 010 Rev-1Mohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Warranty Clause 14Dokument4 SeitenWarranty Clause 14Mohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Production Capacity of Barauni Refinery: MMTPA Million Metric Tonne Per AnnumDokument1 SeiteProduction Capacity of Barauni Refinery: MMTPA Million Metric Tonne Per AnnumMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- HSBC Credit Card T&C SummaryDokument10 SeitenHSBC Credit Card T&C SummaryMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Central Excise GuideDokument62 SeitenCentral Excise GuideMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- MEM No - 010 Rev-1Dokument30 SeitenMEM No - 010 Rev-1Mohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pipeline Engineering: BTG Program For Graduate Engineers Pipeline & City Gas DistributionDokument3 SeitenPipeline Engineering: BTG Program For Graduate Engineers Pipeline & City Gas DistributionMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

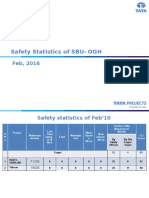

- Safety Statistics of OGH For Feb 16Dokument4 SeitenSafety Statistics of OGH For Feb 16Mohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Central Excise GuideDokument9 SeitenCentral Excise GuideMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- GLOIncoterms IDokument2 SeitenGLOIncoterms IWarren SappNoch keine Bewertungen

- Incoterms Shipping GuideDokument60 SeitenIncoterms Shipping GuidejumbotronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budget Analysis (2011-12)Dokument14 SeitenBudget Analysis (2011-12)Jayesh NairNoch keine Bewertungen

- INCOTermsDokument8 SeitenINCOTermsSanjay GawadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- N"",rio DL-?X: - , LR - Oc - B 'T (Lo TT", - (-,TD' ' "' A'Dokument9 SeitenN"",rio DL-?X: - , LR - Oc - B 'T (Lo TT", - (-,TD' ' "' A'Mohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Risk Management Adv and PitfallsDokument6 SeitenProject Risk Management Adv and PitfallsMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Addendum 1Dokument34 SeitenAddendum 1Mohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer BehaviourDokument43 SeitenConsumer BehaviourMohit AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vis BreakingDokument12 SeitenVis BreakingMohit Arora100% (1)

- Internship ReportDokument33 SeitenInternship Reportananya kapoorNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 Food TourismDokument28 Seiten2014 Food TourismPantazis PastrasNoch keine Bewertungen

- TNM201Final Report2Dokument28 SeitenTNM201Final Report2Nazifa Tasnia Raisa 1813471630Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tourism Code EditedDokument13 SeitenTourism Code EditedJoanne Marie ComaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brainstorming and OutliningDokument7 SeitenBrainstorming and OutliningWalter Evans LasulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Multidimensional Tourism Carrying Capacity Model - An Empirical ApproachDokument16 SeitenA Multidimensional Tourism Carrying Capacity Model - An Empirical Approachita faristaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GR 12 - Tourism - Term 1 - Global Events of International Significance - Revision Question Answers - EcdoeDokument21 SeitenGR 12 - Tourism - Term 1 - Global Events of International Significance - Revision Question Answers - Ecdoebongiweshibe55Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Tourism and Hospitality ProfessionalDokument28 SeitenThe Tourism and Hospitality ProfessionalLovella V. CarilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hotel Front Office ExperienceDokument1 SeiteHotel Front Office ExperienceTwan Darsh (adarsh)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 9 MacroDokument11 SeitenChapter 9 MacroRoy CabarlesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Impacts (Tourism)Dokument12 SeitenCultural Impacts (Tourism)Anvesh VakadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revolution in Central America Replaced by Tenuous Democracies (GEOG382Dokument3 SeitenRevolution in Central America Replaced by Tenuous Democracies (GEOG382jamesbilesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 7 - How Do Many Hearing-Impaired People TalkDokument10 SeitenLesson 7 - How Do Many Hearing-Impaired People TalkJamille NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Proposal On Designingrecreational Tourist Resort: Therme BaiaeDokument8 SeitenThesis Proposal On Designingrecreational Tourist Resort: Therme BaiaeMadiha RehmathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roles of Bangladesh Parjatan Corporation in Developing TourismDokument8 SeitenRoles of Bangladesh Parjatan Corporation in Developing TourismIslam MarufNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal B.inggris Kelompok 3Dokument11 SeitenSoal B.inggris Kelompok 3Muzakki AbdulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tourism - Act - 2005 - 0Dokument51 SeitenTourism - Act - 2005 - 0webmaster@sltdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rizkiatul Kamaliah-Public Discussion - Is Ecotourism Worth ItDokument3 SeitenRizkiatul Kamaliah-Public Discussion - Is Ecotourism Worth ItLia KamalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eyo Festival Origin and SignificanceDokument4 SeitenEyo Festival Origin and SignificanceHenry Rondon100% (1)

- TravelDokument26 SeitenTravelJesi GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Based Homestay Programme A Personal ExpeDokument10 SeitenCommunity Based Homestay Programme A Personal Expejenal abidinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tourism Impacts On The EconomyDokument4 SeitenTourism Impacts On The Economyqueenie esguerraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Newsweek International - 28 05 2021Dokument52 SeitenNewsweek International - 28 05 2021Jose PirulliNoch keine Bewertungen

- 46 118 1 SM PDFDokument17 Seiten46 118 1 SM PDFfaizalhiolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Different Perspectives of Tourism Identified by Mcintosh and GoeldnerDokument2 Seiten4 Different Perspectives of Tourism Identified by Mcintosh and GoeldnerNguyễn Bích NgọcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uganda Tourism Act SummaryDokument27 SeitenUganda Tourism Act Summarympuuga abdunasserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key Outbound Tourism Markets in SE AsiaDokument199 SeitenKey Outbound Tourism Markets in SE AsiaLinhHNguyen100% (2)