Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Sandoval Notes Constitutional Law 2

Hochgeladen von

Michael Rangielo Brion Guzman0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

481 Ansichten23 Seitenconstitutional law reviewer

bill of rights

Originaltitel

Sandoval notes Constitutional law 2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOC, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenconstitutional law reviewer

bill of rights

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOC, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

481 Ansichten23 SeitenSandoval Notes Constitutional Law 2

Hochgeladen von

Michael Rangielo Brion Guzmanconstitutional law reviewer

bill of rights

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOC, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 23

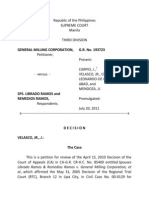

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW

A. THE INHERENT POWERS OF THE STATE

Police Power

1. Define Police Power and clarify its scope.

Held: 1. Police power is an inherent attribute of

sovereignty. It has been defined as the power vested

by the Constitution in the legislature to make, ordain,

and establish all manner of wholesome and reasonable

laws, statutes and ordinances, either with penalties or

without, not repugnant to the Constitution, as they shall

judge to be for the good and welfare of the

commonwealth, and for the subjects of the same. The

power is plenary and its scope is vast and pervasive,

reaching and justifying measures for public health,

public safety, public morals, and the general welfare.

It bears stressing that police power is lodged

primarily in the ational !egislature. It cannot be

e"ercised by any group or body of individuals not

possessing legislative power. The ational

!egislature, however, may delegate this power to the

President and administrative boards as well as the

lawmaking bodies of municipal corporations or local

government units. #nce delegated, the agents can

e"ercise only such legislative powers as are conferred

on them by the national lawmaking body.

(Metropolitan Manila Development Authority v. Bel-

Air Village Association, Inc., 328 !"A 83#, 8$3-

8$$, March 2%, 2&&&, '

st

Div. ()uno*+

$. The scope of police power has been held to

be so comprehensive as to encompass almost all

matters affecting the health, safety, peace, order,

1

morals, comfort and convenience of the community.

Police power is essentially regulatory in nature and the

power to issue licenses or grant business permits, if

e"ercised for a regulatory and not revenue%raising

purpose, is within the ambit of this power.

& " "

'T(he issuance of usiness licenses and

permits by a municipality or city is essentially regulatory

in nature. The authority, which devolved upon local

government units to issue or grant such licenses or

permits, is essentially in the e"ercise of the police

power of the )tate within the contemplation of the

general welfare clause of the !ocal *overnment Code.

(Ace,e-o .ptical !ompany, Inc. v. !ourt o/

Appeals, 320 !"A 3'$, March 3', 2&&&, 1n Banc

()urisima*+

2. Does Article 263(g) of the Labor Code (esting

!pon the "ecretary of Labor the discretion to

deter#ine what ind!stries are indispensable to the

national interest and thereafter$ ass!#e %!risdiction

oer disp!tes in said ind!stries) iolate the wor&ers'

constit!tional right to stri&e(

Held: )aid article does not interfere with the

workers+ right to strike but merely regulates it, when in

the e"ercise of such right, national interests will be

affected. The rights granted by the Constitution are not

absolute. They are still subject to control and limitation

to ensure that they are not e"ercised arbitrarily. The

interests of both the employers and the employees are

intended to be protected and not one of them is given

undue preference.

2

The !abor Code vests upon the )ecretary of

!abor the discretion to determine what industries are

indispensable to national interest. Thus, upon the

determination of the )ecretary of !abor that such

industry is indispensable to the national interest, it will

assume jurisdiction over the labor dispute of said

industry. The assumption of jurisdiction is in the nature

of police power measure. This is done for the

promotion of the common good considering that a

prolonged strike or lockout can be inimical to the

national economy. The )ecretary of !abor acts to

maintain industrial peace. Thus, his certification for

compulsory arbitration is not intended to impede the

workers+ right to strike but to obtain a speedy

settlement of the dispute. ()hiltrea- 2or3ers 4nion

()524* v. !on/esor, 2#0 !"A 303, March '2,

'00%+

3. )ay solicitation for religio!s p!rposes be s!b%ect to

proper reg!lation by the "tate in the e*ercise of

police power(

Held: The constitutional inhibition of legislation

on the subject of religion has a double aspect. #n the

one hand, it forestalls compulsion by law of the

acceptance of any creed or the practice of any form of

worship. ,reedom of conscience and freedom to

adhere to such religious organi-ation or form of

worship as the individual may choose canno! e

res!ric!ed " law. On !#e o!#er #and$ i! safe%uards

!#e free e&ercise of !#e c#osen for' of reli%ion.

Thus, the Constitution embraces two concepts, that is,

freedom to believe and freedom to act. The first is

absolute but, in the nature of things, the second cannot

be. Conduct remains subject to regulation for the

protection of society. The freedom to act must have

appropriate definitions to preserve the enforcement of

3

that protection. In every case, the power to regulate

must be so e"ercised, in attaining a permissible end, as

not to unduly infringe on the protected freedom.

.hence, even the e"ercise of religion may be

regulated, at some slight inconvenience, in order that

the )tate may protect its citi-ens from injury. .ithout

doubt, a )tate may protect its citi-ens from fraudulent

solicitation by re(uirin% a s!ran%er in !#e co''uni!",

before permitting him publicly to solicit funds for any

purpose, !o es!alis# #is iden!i!" and #is au!#ori!"

!o ac! for !#e cause w#ic# #e )ur)or!s !o re)resen!.

The )tate is likewise free to regulate the time and

manner of solicitation generally, in the interest of public

safety, peace, comfort, or convenience.

It does not follow, therefore, from the

constitutional guarantees of the free e"ercise of religion

that everything which may be so called can be

tolerated. It has been said that a law advancing a

legitimate governmental interest is not necessarily

invalid as one interfering with the /free e"ercise0 of

religion merely because it also incidentally has a

detrimental effect on the adherents of one or more

religion. Thus, the general regulation, in the public

interest, of solicitation, which does not involve any

religious test and does not unreasonably obstruct or

delay the collection of funds, is not open to any

constitutional objection, even though the collection be

for a religious purpose. )uch regulation would not

constitute a prohibited previous restraint on the free

e"ercise of religion or interpose an inadmissible

obstacle to its e"ercise.

1ven with numerous regulative laws in

e"istence, it is surprising how many operations are

carried on by persons and associations who, secreting

4

their activities under the guise of benevolent purposes,

succeed in cheating and defrauding a generous public.

It is in fact ama-ing how profitable the fraudulent

schemes and practices are to people who manipulate

them. The )tate has authority under the e"ercise of its

police power to determine whether or not there shall be

restrictions on soliciting by unscrupulous persons or for

unworthy causes or for fraudulent purposes. That

solicitation of contributions under the guise of

charitable and benevolent purposes is grossly abused

is a matter of common knowledge. Certainly the

solicitation of contributions in good faith for worthy

purposes should not be denied, but somewhere should

be lodged the power to determine within reasonable

limits the worthy from the unworthy. The objectionable

practices of unscrupulous persons are prejudicial to

worthy and proper charities which naturally suffer when

the confidence of the public in campaigns for the

raising of money for charity is lessened or destroyed.

)ome regulation of public solicitation is, therefore, in

the public interest.

To conclude$ solici!a!ion for reli%ious

)ur)oses 'a" e su*ec! !o )ro)er re%ula!ion "

!#e S!a!e in !#e e&ercise of )olice )ower. (!enteno

v. Villalon-)ornillos, 23# !"A '0%, ept. ', '00$

("egala-o*+

T#e Power of E'inen! +o'ain

+. ,hat is -#inent Do#ain(

Held: 1. 1minent domain is the right or power

of a sovereign state to appropriate private property to

particular uses to promote public welfare. It is an

indispensable attribute of sovereignty2 a power

5

grounded in the primary duty of government to serve

the common need and advance the general welfare.

Thus, the right of eminent domain appertains to every

independent government without the necessity for

constitutional recognition. The provisions found in

modern constitutions of civili-ed countries relating to

the taking of property for the public use do not by

implication grant the power to the government, but limit

a power which would otherwise be without limit. Thus,

our own Constitution provides that /'p(rivate property

shall not be taken for public use without just

compensation.0 (Art. ...$ "ec. /). ,urthermore, the due

process and e3ual protection clauses (1/01

Constit!tion$ Art. ...$ "ec. 1) act as additional

safeguards against the arbitrary e"ercise of this

governmental power.

)ince the e"ercise of the power of eminent

domain affects an individual+s right to private property,

a constitutionally%protected right necessary for the

preservation and enhancement of personal dignity and

intimately connected with the rights to life and liberty$

the need for its circumspect operation cannot be

overemphasi-ed. In City of )anila . Chinese

Co##!nity of )anila we said (+2 Phil. 3+/ 31/1/)4

The e"ercise of the right of eminent

domain, whether directly by the )tate, or by its

authori-ed agents, is necessarily in derogation

of private rights, and the rule in that case is that

the authority must be strictly construed. o

species of property is held by individuals with

greater tenacity, and none is guarded by the

Constitution and the laws more sedulously, than

the right to the freehold of inhabitants. .hen

the legislature interferes with that right, and, for

greater public purposes, appropriates the land of

6

ah individual without his consent, the plain

meaning of the law should not be enlarged by

doubt'ful( interpretation. (4ensley .

)o!ntainla&e ,ater Co.$ 13 Cal.$ 326 and cases

cited 313 A#. Dec.$ 5166)

The statutory power of taking property from the

owner without his consent is one of the most delicate

e"ercise of governmental authority. It is to be watched

with jealous scrutiny. Important as the power may be

to the government, the inviolable sanctity which all free

constitutions attach to the right of property of the

citi-ens, constrains the strict observance of the

substantial provisions of the law which are prescribed

as modes of the e"ercise of the power, and to protect it

from abuse " " ".

The power of eminent domain is essentially

legislative in nature. It is firmly settled, however, that

such power may be validly delegated to local

government units, other public entities and public

utilities, although the scope of this delegated legislative

power is necessarily narrower than that of the

delegating authority and may only be e"ercised in strict

compliance with the terms of the delegating law.

(6eirs o/ Al,erto uguitan v. !ity o/ Man-aluyong,

328 !"A '3%, '$$-'$#, March '$, 2&&&, 3

r-

Div.

(7on8aga-"eyes*+

$. 1minent domain is a fundamental )tate

power that is inseparable from sovereignty. It is

government+s right to appropriate, in the nature of a

compulsory sale to the )tate, private property for public

use or purpose. Inherently possessed by the national

legislature, the power of eminent domain may be

validly delegated to local governments, other public

entities and public utilities. ,or the taking of private

7

property by the government to be valid, the taking must

be for public purpose and there must be just

compensation. (Mo-ay v. !ourt o/ Appeals, 2#8

!"A 98#, :e,ruary 2&, '00%+

5. "tate so#e li#itations on the e*ercise of the power

of -#inent Do#ain.

Held: The limitations on the power of eminent

domain are that the use must be public, compensation

must be made and due process of law must be

observed. The )upreme Court, taking cogni-ance of

such issues as the ade3uacy of compensation,

necessity of the taking and the public use character or

the purpose of the taking, has ruled that the necessity

of e"ercising eminent domain must be genuine and of a

public character. *overnment may not capriciously

choose what private property should be taken.

(Mo-ay v. !ourt o/ Appeals, 2#8 !"A 98#,

:e,ruary 2&, '00%+

6. Disc!ss the e*panded notion of p!blic !se in

e#inent do#ain proceedings.

Held: The City of 5anila, acting through its

legislative branch, has the e"press power to ac3uire

private lands in the city and subdivide these lands into

home lots for sale to bona fide tenants or occupants

thereof, and to laborers and low%salaried employees of

the city.

That only a few could actually benefit from the

e"propriation of the property does not diminish its

public character. It is simply not possible to provide all

at once land and shelter for all who need them.

8

Corollary to the e"panded notion of public use,

e"propriation is not anymore confined to vast tracts of

land and landed estates. It is therefore of no moment

that the land sought to be e"propriated in this case is

less than half a hectare only.

T#rou%# !#e "ears$ !#e )ulic use

re(uire'en! in e'inen! do'ain #as e,ol,ed in!o a

fle&ile conce)!$ influenced " c#an%in%

condi!ions. Pulic use now includes !#e roader

no!ion of indirec! )ulic enefi! or ad,an!a%e$

includin% in )ar!icular$ uran land refor' and

#ousin%. (:ilstream International Incorporate- v.

!A, 28$ !"A %'#, ;an. 23, '008 (:rancisco*+

1. 7he constit!tionality of "ec. /2 of 4.P. 4lg. 001

(re8!iring radio and teleision station owners and

operators to gie to the Co#elec radio and

teleision ti#e free of charge) was challenged on

the gro!nd$ a#ong others$ that it iolated the d!e

process cla!se and the e#inent do#ain proision

of the Constit!tion by ta&ing airti#e fro# radio and

teleision broadcasting stations witho!t pay#ent of

%!st co#pensation. Petitioners clai# that the

pri#ary so!rce of reen!e of radio and teleision

stations is the sale of airti#e to adertisers and that

to re8!ire these stations to proide free airti#e is to

a!thori9e a ta&ing which is not :a de #ini#is

te#porary li#itation or restraint !pon the !se of

priate property.; ,ill yo! s!stain the challenge(

Held: 6ll broadcasting, whether by radio or by

television stations, is licensed by the government.

6irwave fre3uencies have to be allocated as there are

more individuals who want to broadcast than there are

fre3uencies to assign. 6 franchise is thus a privilege

subject, among other things, to amendment by

9

Congress in accordance with the constitutional

provision that /any such franchise or right granted " " "

shall be subject to amendment, alteration or repeal by

the Congress when the common good so re3uires.0

(Art. <..$ "ec. 11)

Indeed, provisions for Comelec Time have been

made by amendment of the franchises of radio and

television broadcast stations and such provisions have

not been thought of as taking property without just

compensation. 6rt. &II, )ec. 11 of the Constitution

authori-es the amendment of franchises for /the

common good.0 .hat better measure can be

conceived for the common good than one for free

airtime for the benefit not only of candidates but even

more of the public, particularly the voters, so that they

will be fully informed of the issues in an election7 /'I(t

is the right of the viewers and listeners, not the right of

the broadcasters, which is paramount.0

or indeed can there be any constitutional

objection to the re3uirement that broadcast stations

give free airtime. 1ven in the 8nited )tates, there are

responsible scholars who believe that government

controls on broadcast media can constitutionally be

instituted to ensure diversity of views and attention to

public affairs to further the system of free e"pression.

,or this purpose, broadcast stations may be re3uired to

give free airtime to candidates in an election.

In truth, radio and television broadcasting

companies, which are given franchises, do not own the

airwaves and fre3uencies through which they transmit

broadcast signals and images. They are merely given

the temporary privilege of using them. )ince a

franchise is a mere privilege, the e"ercise of the

privilege may reasonably be burdened with the

10

performance by the grantee of some form of public

service.

In the granting of the privilege to operate

broadcast stations and thereafter supervising radio and

television stations, the )tate spends considerable

public funds in licensing and supervising such stations.

It would be strange if it cannot even re3uire the

licensees to render public service by giving free airtime.

The claim that petitioner would be losing

P9$,:;<,<<<.<< in unreali-ed revenue from advertising

is based on the assumption that airtime is /finished

product0 which, it is said, become the property of the

company, like oil produced from refining or similar

natural resources after undergoing a process for their

production. 6s held in =ed Lion 4roadcasting Co. .

>.C.C. (3/5 ?.". at 3/+$ 23 L. -d. 2d at 3/1$ 8!oting

+1 ?.".C. "ec. 321)$ which upheld the right of a party

personally attacked to reply, /licenses to broadcast do

not confer ownership of designated fre3uencies, but

only the temporary privilege of using them.0

Conse3uently, /a license permits broadcasting, but the

licensee has no constitutional right to be the one who

holds the license or to monopoli-e a radio fre3uency to

the e"clusion of his fellow citi-ens. There is nothing in

the ,irst 6mendment which prevents the government

from re3uiring a licensee to share his fre3uency with

others and to conduct himself as a pro"y or fiduciary

with obligations to present those views and voices

which are representative of his community and which

would otherwise, by necessity, be barred from the

airwaves.0 6s radio and television broadcast stations

do not own the airwaves, no private property is taken

by the re3uirement that they provide airtime to the

Comelec. (51<1BA), Inc. v. !.M1<1!, 280 !"A

33%, April 2', '008 (Men-o8a*+

11

0. )ay e#inent do#ain be barred by @res %!dicata@ or

@law of the case@(

Held: The principle of res %!dicata$ which finds

application in generally all cases and proceedings,

cannot bar the right of the )tate or its agents to

e"propriate private property. The very nature of

eminent domain, as an inherent power of the )tate,

dictates that the right to e"ercise the power be absolute

and unfettered even by a prior judgment or res

%!dicata. T#e sco)e of e'inen! do'ain is )lenar"

and$ li-e )olice )ower$ can .reac# e,er" for' of

)ro)er!" w#ic# !#e S!a!e 'i%#! need for )ulic

use./ 6ll separate interests of individuals in property

are held of the government under this tacit agreement

or implied reservation. otwithstanding the grant to

individuals, the e#inent do#ain$ the highest and most

e"act idea of property, remains in the government, or in

the aggregate body of the people in their sovereign

capacity2 and they have the right to resume the

possession of the property whenever the public interest

re3uires it.0 Thus, the )tate or its authori-ed agent

cannot be forever barred from e"ercising said right by

reason alone of previous non%compliance with any

legal re3uirement.

.hile the principle of res %!dicata does not

denigrate the right of the )tate to e"ercise eminent

domain, it does apply to specific issues decided in a

previous case. ,or e"ample, a final judgment

dismissing an e"propriation suit on the ground that

there was no prior offer precludes another suit raising

the same issue2 i! canno!$ #owe,er$ ar !#e S!a!e or

i!s a%en! fro' !#ereaf!er co')l"in% wi!# !#is

re(uire'en!$ as )rescried " law$ and

suse(uen!l" e&ercisin% i!s )ower of e'inen!

12

do'ain o,er !#e sa'e )ro)er!". (Municipality o/

)arana=ue v. V.M. "ealty !orporation, 202 !"A

#%8, ;uly 2&, '008 ()angani,an*+

/. Disc!ss how e*propriation #ay be initiated$ and the

two stages in e*propriation.

Held: 1"propriation may be initiated by court

action or by legislation. In both instances, just

compensation is determined by the courts (-PAA .

D!lay$ 1+/ "C=A 325 31/016).

The e"propriation of lands consists of two

stages. 6s e"plained in )!nicipality of 4inan . Barcia

(102 "C=A 516$ 503C50+ 31/0/6$ reiterated in Dational

Power Corp. . Eocson$ 226 "C=A 522 31//26)F

The first is concerned with the

determination of the authority of the plaintiff to

e"ercise the power of eminent domain and the

propriety of its e"ercise in the conte"t of the

facts involved in the suit. It ends with an order, if

not dismissal of the action, =of condemnation

declaring that the plaintiff has a lawful right to

take the property sought to be condemned, for

the public use or purpose declared in the

complaint, upon the payment of just

compensation to be determined as of the date of

the filing of the complaint= " " ".

The second phase of the eminent domain

action is concerned with the determination by

the court of =the just compensation for the

property sought to be taken.= This is done by

the court with the assistance of not more than

three >:? commissioners " " ".

13

It is only upon the completion of these two

stages that e"propriation is said to have been

completed. 5oreover, it is only upon payment of just

compensation that title over the property passes to the

government. Therefore, until the action for

e"propriation has been completed and terminated,

ownership over the property being e"propriated

remains with the registered owner. Conse3uently, the

latter can e"ercise all rights pertaining to an owner,

including the right to dispose of his property, subject to

the power of the )tate ultimately to ac3uire it through

e"propriation. ("epu,lic v. alem Investment

!orporation, et. al., 7.". >o. '3%9#0, ;une 23, 2&&&,

2

n-

Div. (Men-o8a*+

12. Does the two (2) stages in e*propriation apply only

to %!dicial$ and not to legislatie$ e*propriation(

Held: The @e la Aamas are mistaken in arguing

that the two stages of e"propriation " " " only apply to

judicial, and not to legislative, e"propriation. 6lthough

Congress has the power to determine what land to

take, it can not do so arbitrarily. Budicial determination

of the propriety of the e"ercise of the power, for

instance, in view of allegations of partiality and

prejudice by those adversely affected$ and the just

compensation for the subject property is provided in

our constitutional system.

.e see no point in distinguishing between

judicial and legislative e"propriation as far as the two

stages mentioned above are concerned. Coth involve

these stages and in both the process is not completed

until payment of just compensation is made. The Court

of 6ppeals was correct in saying that C.P. Clg. :D< did

not effectively e"propriate the land of the @e la Aamas.

14

6s a matter of fact, it merely commenced the

e"propriation of the subject property.

& " "

The @e la Aamas make much of the fact that

ownership of the land was transferred to the

government because the e3uitable and the beneficial

title was already ac3uired by it in 1E;:, leaving them

with only the naked title. Fowever, as this Court held in

Association of "#all Landowners in the Phil.$ .nc. .

"ecretary of Agrarian =efor# (115 "C=A 3+3$ 30/

31/0/6)F

T#e reco%ni0ed rule$ indeed$ is !#a!

!i!le !o !#e )ro)er!" e&)ro)ria!ed s#all )ass

fro' !#e owner !o !#e e&)ro)ria!or onl" u)on

full )a"'en! of !#e *us! co')ensa!ion.

1uris)rudence on !#is se!!led )rinci)le is

consis!en! o!# #ere and in o!#er de'ocra!ic

*urisdic!ions. & " "

("epu,lic v. alem Investment !orporation, et. al.,

7.". >o. '3%9#0, ;une 23, 2&&&, 2

n-

Div. (Men-o8a*+

11. .s prior !ns!ccessf!l negotiation a condition

precedent for the e*ercise of e#inent do#ain(

Held: Citing .ron and "teel A!thority . Co!rt of

Appeals (2+/ "C=A 530$ Gctober 25$ 1//5)$ petitioner

insists that before eminent domain may be e"ercised

by the state, there must be a showing of prior

unsuccessful negotiation with the owner of the property

to be e"propriated.

This contention is not correct. 6s pointed out by

the )olicitor *eneral the current effective law on

delegated authority to e"ercise the power of eminent

15

domain is found in )ection 1$, Cook III of the Aevised

6dministrative Code, which provides4

/)1C. 1$. Power of -#inent Do#ain G

The President shall determine when it is

necessary or advantageous to e"ercise the

power of eminent domain in behalf of the

ational *overnment, and direct the )olicitor

*eneral, whenever he deems the action

advisable, to institute e"propriation proceedings

in the proper court.0

The foregoing provision does not re3uire prior

unsuccessful negotiation as a condition precedent for

the e"ercise of eminent domain. In .ron and "teel

A!thority . Co!rt of Appeals$ the President chose to

prescribe this condition as an additional re3uirement

instead. In the instant case, however, no such

voluntary restriction was imposed. (MI Development

!orporation v. "epu,lic, 323 !"A 8#2, ;an. 28,

2&&&, 3

r-

Div. ()angani,an*+

T#e Power of Ta&a!ion

12. Can ta*es be s!b%ect to offCsetting or

co#pensation(

Held: Ta"es cannot be subject to compensation

for the simple reason that the government and the

ta"payer are not creditors and debtors of each other.

There is a material distinction between a ta" and debt.

@ebts are due to the *overnment in its corporate

capacity, while ta"es are due to the *overnment in its

sovereign capacity. It must be noted that a

distinguishing feature of a ta" is that it is compulsory

rather than a matter of bargain. Fence, a ta" does not

16

depend upon the consent of the ta"payer. If any

ta"payer can defer the payment of ta"es by raising the

defense that it still has a pending claim for refund or

credit, this would adversely affect the government

revenue system. 6 ta"payer cannot refuse to pay his

ta"es when they fall due simply because he has a

claim against the government or that the collection of a

ta" is contingent on the result of the lawsuit it filed

against the government. ()hile? Mining !orporation

v. !ommissioner o/ Internal "evenue, 20$ !"A

#8%, Aug. 28, '008 ("omero*+

13. ?nder Article H.$ "ection 20$ paragraph 3 of the

1/01 Constit!tion$ @3C6haritable instit!tions$

ch!rches and parsonages or conents app!rtenant

thereto$ #os8!es$ nonCprofit ce#eteries$ and all

lands$ b!ildings$ and i#proe#ents$ act!ally$

directly and e*cl!siely !sed for religio!s$

charitable or ed!cational p!rposes shall be e*e#pt

fro# ta*ation.@ I)CA clai#s that the inco#e

earned by its b!ilding leased to priate entities and

that of its par&ing space is li&ewise coered by said

e*e#ption. =esole.

Held: The debates, interpellations and

e"pressions of opinion of the framers of the

Constitution reveal their intent that which, in turn, may

have guided the people in ratifying the Charter. )uch

intent must be effectuated.

6ccordingly, Bustice Filario *. @avide, Br., a

former constitutional commissioner, who is now a

member of this Court, stressed during the Concom

debates that =" " " what is e"empted is not the

institution itself " " "2 those e"empted from real estate

ta"es are lands, buildings and improvements actually,

directly and e"clusively used for religious, charitable or

17

educational purposes. ,ather Boa3uin *. Cernas, an

eminent authority on the Constitution and also a

member of the Concom, adhered to the same view that

the e"emption created by said provision pertained only

to property ta"es.

In his treatise on ta"ation, 5r. Bustice Bose C.

Hitug concurs, stating that ='t(he ta" e"emption covers

property ta"es only.= (!ommissioner o/ Internal

"evenue v. !A, 208 !"A 83, .ct. '$, '008

()angani,an*+

1+. ?nder Article <.H$ "ection +$ paragraph 3 of the

1/01 Constit!tion$ @3A6ll reen!es and assets of

nonCstoc&$ nonCprofit ed!cational instit!tions !sed

act!ally$ directly$ and e*cl!siely for ed!cational

p!rposes shall be e*e#pt fro# ta*es and d!ties.@

I)CA alleged that it @is a nonCprofit ed!cational

instit!tion whose reen!es and assets are !sed

act!ally$ directly and e*cl!siely for ed!cational

p!rposes so it is e*e#pt fro# ta*es on its

properties and inco#e.@

Held: .e reiterate that private respondent is

e"empt from the payment of property ta", but not

income ta" on the rentals from its property. The bare

allegation alone that it is a non%stock, non%profit

educational institution is insufficient to justify its

e"emption from the payment of income ta".

'!(aws allowing ta" e"emption are construed

strictissi#i %!ris. Fence, for the I5C6 to be granted

the e"emption it claims under the abovecited provision,

it must prove with substantial evidence that >1? it falls

under the classification nonCstoc&$ nonCprofit

ed!cational instit!tionJ and >$? the income it seeks to

be e"empted from ta"ation is !sed act!ally$ directly$

18

and e*cl!siely for ed!cational p!rposes. Fowever,

the Court notes that not a scintilla of evidence was

submitted by private respondent to prove that it met the

said re3uisites. (!ommissioner o/ Internal "evenue

v. !A, 208 !"A 83, .ct. '$, '008 ()angani,an*+

15. .s the I)CA an ed!cational instit!tion within the

p!riew of Article <.H$ "ection +$ par. 3 of the

Constit!tion(

Held: .e rule that it is not. The term

=educational institution= or =institution of learning= has

ac3uired a well%known technical meaning, of which the

members of the Constitutional Commission are

deemed cogni-ant. 8nder the 1ducation 6ct of 1E;$,

such term refers to schools. The school system is

synonymous with formal education, which =refers to the

hierarchically structured and chronologically graded

learnings organi-ed and provided by the formal school

system and for which certification is re3uired in order

for the learner to progress through the grades or move

to the higher levels.= The Court has e"amined the

=6mended 6rticles of Incorporation= and =Cy%!aws= of

the I5C6, but found nothing in them that even hints

that it is a school or an educational institution.

,urthermore, under the 1ducation 6ct of 1E;$,

even non%formal education is understood to be school%

based and =private auspices such as foundations and

civic%spirited organi-ations= are ruled out. It is settled

that the term =educational institution,= when used in

laws granting ta" e"emptions, refers to a =" " " school

seminary, college or educational establishment " " ".=

(0+ CE" 566) Therefore, the private respondent cannot

be deemed one of the educational institutions covered

by the constitutional provision under consideration.

19

(!ommissioner o/ Internal "evenue v. !A, 208

!"A 83, .ct. '$, '008 ()angani,an*+

16. )ay the PCBB alidly co##it to e*e#pt fro# all

for#s of ta*es the properties to be retained by the

)arcos heirs in a Co#pro#ise Agree#ent between

the for#er and the latter(

Held: The power to ta" and to grant e"emptions

is vested in the Congress and, to a certain e"tent, in

the local legislative bodies. )ection $;>D?, 6rticle HI of

the Constitution, specifically provides4 /o law granting

any ta" e"emption shall be passed without the

concurrence of a majority of all the members of the

Congress.0 The PC** has absolutely no power to

grant ta" e"emptions, even under the cover of its

authority to compromise ill%gotten wealth cases.

1ven granting that Congress enacts a law

e"empting the 5arcoses from paying ta"es on their

properties, such law will definitely not pass the test of

the e3ual protection clause under the Cill of Aights.

6ny special grant of ta" e"emption in favor only of the

5arcos heirs will constitute class legislation. It will also

violate the constitutional rule that /!a&a!ion s#all e

unifor' and e(ui!ale.@ (!have8 v. )!77, 200

!"A %$$, Dec. 0, '008 ()angani,an*+

11. Disc!ss the p!rpose of ta* treaties(

Held: The AP%8) Ta" Treaty is just one of a

number of bilateral treaties which the Philippines has

entered into for the avoidance of double ta"ation. The

purpose of these international agreements is to

reconcile the national fiscal legislations of the

contracting parties in order to help the ta"payer avoid

simultaneous ta"ation in two different jurisdictions.

20

5ore precisely, the ta" conventions are drafted with a

view towards the elimination of international %!ridical

do!ble ta*ation " " ". (!ommissioner o/ Internal

"evenue v. .!. ;ohnson an- on, Inc., 3&0 !"A

8%, '&'-'&2, ;une 29, '000, 3

r-

Div. (7on8aga-

"eyes*+

10. ,hat is @international %!ridical do!ble ta*ation@(

Held: It is defined as the imposition of

comparable ta"es in two or more states on the same

ta"payer in respect of the same subject matter and for

identical periods. (!ommissioner o/ Internal

"evenue v. .!. ;ohnson an- on, Inc., 3&0 !"A

8%, '&2, ;une 29, '000+

1/. ,hat is the rationale for doing away with

international %!ridical do!ble ta*ation( ,hat are

the #ethods resorted to by ta* treaties to eli#inate

do!ble ta*ation(

Held: The apparent rationale for doing away

with double ta"ation is to encourage the free flow of

goods and services and the movement of capital,

technology and persons between countries, conditions

deemed vital in creating robust and dynamic

economies. ,oreign investments will only thrive in a

fairly predictable and reasonable international

investment climate and the protection against double

ta"ation is crucial in creating such a climate.

@ouble ta"ation usually takes place when a

person is resident of a contracting state and derives

income from, or owns capital in, the other contracting

state and both states impose ta" on that income or

capital. In order to eliminate double ta"ation, a ta"

treaty resorts to several methods. ,irst, it sets out the

21

respective rights to ta" of the state of source or situs

and of the state of residence with regard to certain

classes of income or capital. In some cases, an

e"clusive right to ta" is conferred on one of the

contracting states2 however, for other items of income

or capital, both states are given the right to ta",

although the amount of ta" that may be imposed by the

state of source is limited.

The second method for the elimination of double

ta"ation applies whenever the state of source is given a

full or limited right to ta" together with the state of

residence. In this case, the treaties make it incumbent

upon the state of residence to allow relief in order to

avoid double ta"ation. There are two methods of relief

% the e"emption method and the credit method. In the

e"emption method, the income or capital which is

ta"able in the state of source or situs is e"empted in

the state of residence, although in some instances it

may be taken into account in determining the rate of

ta" applicable to the ta"payerJs remaining income or

capital. #n the other hand, in the credit method,

although the income or capital which is ta"ed in the

state of source is still ta"able in the state of residence,

the ta" paid in the former is credited against the ta"

levied in the latter. The basic difference between the

two methods is that in the e"emption method, the focus

is on the income or capital itself, whereas the credit

method focuses upon the ta". (!ommissioner o/

Internal "evenue v. .!. ;ohnson an- on, Inc.,

3&0 !"A 8%, '&2-'&3, ;une 29, '000+

22. ,hat is the rationale for red!cing the ta* rate in

negotiating ta* treaties(

Held: In negotiating ta" treaties, the underlying

rationale for reducing the ta" rate is that the Philippines

22

will give up a part of the ta" in the e"pectation that the

ta" given up for this particular investment is not ta"ed

by the other country. (!ommissioner o/ Internal

"evenue v. .!. ;ohnson an- on, Inc., 3&0 !"A

8%, '&3, ;une 29, '000+

23

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Final Exam Civ LawDokument6 SeitenFinal Exam Civ LawBass TēhNoch keine Bewertungen

- CivPro Jara NotesDokument145 SeitenCivPro Jara NotesLangley Gratuito100% (4)

- Sample of PleadingsDokument4 SeitenSample of PleadingsBianca Beltran100% (2)

- Constitutional Review SandovalDokument109 SeitenConstitutional Review SandovalAndro Julio QuimpoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stag Preweek Notes Political Law 2019 Final For ReleaseDokument37 SeitenStag Preweek Notes Political Law 2019 Final For ReleaseRiel Picardal-VillalonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor ReviewerDokument146 SeitenLabor Reviewerchan.aNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar 2021 LawsDokument24 SeitenBar 2021 LawsKrisdenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part 1 Political Law Reviewer by Atty SandovalDokument153 SeitenPart 1 Political Law Reviewer by Atty SandovalLoraine RingonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 006 Republic Vs Sandiganbayan 662 Scra 152Dokument109 Seiten006 Republic Vs Sandiganbayan 662 Scra 152Maria Jeminah TurarayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial Law) Civil Procedure) Notes of Rene Callanta) Made Early Part of 2000 (Est) ) 123 PagesDokument118 SeitenRemedial Law) Civil Procedure) Notes of Rene Callanta) Made Early Part of 2000 (Est) ) 123 PagesbubblingbrookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law Last Minute TipsDokument54 SeitenCriminal Law Last Minute TipsPaula GasparNoch keine Bewertungen

- UPRevised Ortega Lecture Notes IIDokument159 SeitenUPRevised Ortega Lecture Notes IISafenaz MutilanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recent Jurisprudence 2010 - May 2016 Prof Alexis Medina Draft 4.15 Part 1Dokument137 SeitenRecent Jurisprudence 2010 - May 2016 Prof Alexis Medina Draft 4.15 Part 1alyamarrabeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law DLSu Part PDFDokument40 SeitenCriminal Law DLSu Part PDFJose JarlathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests Compilation - Torts and Damages PDFDokument49 SeitenCase Digests Compilation - Torts and Damages PDFSheila RosetteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application LetterDokument1 SeiteApplication LetterStephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics Bathan CasesDokument20 SeitenEthics Bathan CasesBam BathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Encarnacion BanogonDokument1 SeiteEncarnacion BanogonPearl Angeli Quisido CanadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Order Denying Motion To QuashDokument2 SeitenOrder Denying Motion To QuashArjay Elnas0% (1)

- Civil Cases Marriage Psychological Incapacity Part 2Dokument176 SeitenCivil Cases Marriage Psychological Incapacity Part 2Hamid DSNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 AUSL LMT Legal Ethics Draft PDFDokument14 Seiten2019 AUSL LMT Legal Ethics Draft PDFJo GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Print - Siliman Civ QnawDokument231 SeitenPrint - Siliman Civ QnawbubblingbrookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adonis Notes 2011Dokument169 SeitenAdonis Notes 2011Ron GamboaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lim Teck Chuan Vs Uy (752 SCRA 268)Dokument20 SeitenLim Teck Chuan Vs Uy (752 SCRA 268)Mark Gabriel B. Maranga100% (1)

- Last Minute Materials Judge CampanillaDokument7 SeitenLast Minute Materials Judge CampanillaNica Nebreja100% (1)

- Political Law 306 Questions in Pol Law BDokument143 SeitenPolitical Law 306 Questions in Pol Law BNashiba Dida-AgunNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESCRA - Theory of The CaseDokument24 SeitenESCRA - Theory of The Casebatusay575Noch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Law DoctrinesDokument30 SeitenLabor Law DoctrinesOnat PNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases in Crim Outline Justice LopezDokument185 SeitenCases in Crim Outline Justice Lopezimianmorales100% (1)

- Pals Legal Ethics ReviewedDokument66 SeitenPals Legal Ethics ReviewedRaymund Christian Ong AbrantesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mogello - Siliman Answers To BarDokument244 SeitenMogello - Siliman Answers To BarMaria Izza Nicola KatonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018 Syllabus Pol Pil PDFDokument110 Seiten2018 Syllabus Pol Pil PDFRatio DecidendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 DOJ Free Bar Notes in Criminal LawDokument7 Seiten2017 DOJ Free Bar Notes in Criminal LawMarcelino CasilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar ExaminersDokument2 SeitenBar ExaminersAngelo Raphael B. DelmundoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oral ArgumentDokument2 SeitenOral ArgumentAlyza Montilla BurdeosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Testate Estate of Joseph G. Brimo, JUAN MICIANO, Administrator vs. Andre BrimoDokument12 SeitenTestate Estate of Joseph G. Brimo, JUAN MICIANO, Administrator vs. Andre BrimoHaze Q.Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Heirs of Alfredo CulladoDokument11 SeitenThe Heirs of Alfredo CulladoBrandon BanasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judge Gito Strategic Lecture in Political LawDokument354 SeitenJudge Gito Strategic Lecture in Political LawOpsOlavario100% (1)

- Dlsu Lcbo Political and International Law Animo Notes 2018Dokument83 SeitenDlsu Lcbo Political and International Law Animo Notes 2018Rachelle CasimiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- RemRev - Señga Case Doctrines (Leonen) (4E1920)Dokument157 SeitenRemRev - Señga Case Doctrines (Leonen) (4E1920)Naethan Jhoe L. CiprianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor DawayDokument41 SeitenLabor DawayMitchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Labor Law Justice Leonen Case DigestsDokument34 Seiten2 Labor Law Justice Leonen Case DigestsPonkan BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines Regional Trial CourtDokument3 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Regional Trial CourtJFANoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 164679 (Admin. Case Over Retired Emloyee)Dokument10 SeitenG.R. No. 164679 (Admin. Case Over Retired Emloyee)Mikee RañolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pale Cases 1Dokument166 SeitenPale Cases 1gay cambeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Tips in Answering Bar Exam Questions: Atty. Abelardo Domondon, Jurists Bar Review CenterDokument5 Seiten5 Tips in Answering Bar Exam Questions: Atty. Abelardo Domondon, Jurists Bar Review CenterMarko KasaysayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 139Dokument9 SeitenRule 139aquanesse21Noch keine Bewertungen

- "Conflict of Interest" of Corporate LawyersDokument29 Seiten"Conflict of Interest" of Corporate LawyersJeff FernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Review MethodsDokument3 SeitenBar Review MethodsRamon MasagcaNoch keine Bewertungen

- FERNANDO V GARMA - Reply To AnswerDokument18 SeitenFERNANDO V GARMA - Reply To AnswerHencel GumabayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prac Court ReactionDokument1 SeitePrac Court ReactionRia Kriselle Francia PabaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Reports Annotated 823Dokument57 SeitenSupreme Court Reports Annotated 823Janice LivingstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tilted Justice: First Came the Flood, Then Came the Lawyers.Von EverandTilted Justice: First Came the Flood, Then Came the Lawyers.Noch keine Bewertungen

- (What Is The Prevailing Statute/ Rule?Dokument16 Seiten(What Is The Prevailing Statute/ Rule?Cheala ManagayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Goro SpeDokument195 SeitenGoro SpeKR ReborosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Notes 2Dokument66 SeitenCase Notes 2Ron Jacob AlmaizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definition of Terms: State, People, Territory, Government and SovereigntyDokument35 SeitenDefinition of Terms: State, People, Territory, Government and SovereigntyKeith MarianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digested CasesDokument38 SeitenDigested CasesJaelein Nicey A. Monteclaro100% (1)

- Act #4 - Tandog, Judie Lee M. FSM 31Dokument6 SeitenAct #4 - Tandog, Judie Lee M. FSM 31Judie Lee TandogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Due ProcessDokument7 SeitenDue ProcessArciere Jeonsa100% (1)

- Constitutional Law II (Gabriel)Dokument194 SeitenConstitutional Law II (Gabriel)trishayaokasin100% (1)

- Leg Med 9Dokument28 SeitenLeg Med 9Bianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- 30s Elbow 30s Rest 30s B, Sic 30s Rest 30s Elbow 15s Right Side PL, NK 30s Rest 15s Left Side PL, NK 6x3 Push UpsDokument1 Seite30s Elbow 30s Rest 30s B, Sic 30s Rest 30s Elbow 15s Right Side PL, NK 30s Rest 15s Left Side PL, NK 6x3 Push UpsBianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Second Division Rico Rommel Atienza, G.R. No. 177407: ChairpersonDokument15 SeitenSecond Division Rico Rommel Atienza, G.R. No. 177407: ChairpersonBianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presidential Decree No 1829 - Obstruction of JusticeDokument4 SeitenPresidential Decree No 1829 - Obstruction of JusticeBianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leg Med 5Dokument32 SeitenLeg Med 5Bianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- (G.R. Nos. 96027-28. March 08, 2005) : Resolution PUNO, J.Dokument26 Seiten(G.R. Nos. 96027-28. March 08, 2005) : Resolution PUNO, J.Bianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Special Penal LawDokument42 SeitenSpecial Penal LawBianca Beltran100% (2)

- ObliCon - Cases - 1240 To 1258Dokument159 SeitenObliCon - Cases - 1240 To 1258Bianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- LegMed - Medical Negligence Cases DigestDokument115 SeitenLegMed - Medical Negligence Cases DigestBianca Beltran100% (4)

- Supreme Court: Leonen, Ramirez & Associates For Petitioner. Constante A. Ancheta For Private RespondentsDokument10 SeitenSupreme Court: Leonen, Ramirez & Associates For Petitioner. Constante A. Ancheta For Private RespondentsBianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Milling Corp. V Spouses Ramos, GR No. 193723Dokument11 SeitenGeneral Milling Corp. V Spouses Ramos, GR No. 193723Bianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- ObliCon - Cases - 1240 To 1258Dokument159 SeitenObliCon - Cases - 1240 To 1258Bianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geluz Vs CA, 2 Scra 801Dokument3 SeitenGeluz Vs CA, 2 Scra 801Bianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen