Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

J Interpers Violence 2012 Lim 2039 61

Hochgeladen von

Amapola Lustre0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

9 Ansichten24 SeitenSelf-Worth as a Mediator Between Attachment and Posttraumatic Stress in Interpersonal Trauma Ban Hong (Phylice) Lim, Lauren A. Adams and Michelle M. Lilly Stress in Interpersonal Trauma Self-Worth as a Mediator Between Attachment and Posttraumatic Stress in interpersonal trauma.

Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenSelf-Worth as a Mediator Between Attachment and Posttraumatic Stress in Interpersonal Trauma Ban Hong (Phylice) Lim, Lauren A. Adams and Michelle M. Lilly Stress in Interpersonal Trauma Self-Worth as a Mediator Between Attachment and Posttraumatic Stress in interpersonal trauma.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

9 Ansichten24 SeitenJ Interpers Violence 2012 Lim 2039 61

Hochgeladen von

Amapola LustreSelf-Worth as a Mediator Between Attachment and Posttraumatic Stress in Interpersonal Trauma Ban Hong (Phylice) Lim, Lauren A. Adams and Michelle M. Lilly Stress in Interpersonal Trauma Self-Worth as a Mediator Between Attachment and Posttraumatic Stress in interpersonal trauma.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 24

http://jiv.sagepub.

com/

Violence

Journal of Interpersonal

http://jiv.sagepub.com/content/27/10/2039

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0886260511431440

2012 27: 2039 originally published online 10 February 2012 J Interpers Violence

Ban Hong (Phylice) Lim, Lauren A. Adams and Michelle M. Lilly

Stress in Interpersonal Trauma

Self-Worth as a Mediator Between Attachment and Posttraumatic

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children

can be found at: Journal of Interpersonal Violence Additional services and information for

http://jiv.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://jiv.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://jiv.sagepub.com/content/27/10/2039.refs.html Citations:

What is This?

- Feb 10, 2012 OnlineFirst Version of Record

- Jun 3, 2012 Version of Record >>

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Journal of Interpersonal Violence

27(10) 2039 2061

The Author(s) 2012

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0886260511431440

http://jiv.sagepub.com

431440JIV271010.1177/088626051143144

0Lim et al.Journal of Interpersonal Violence

The Author(s) 2012

Reprints and permission: http://www.

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

1

Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL, USA

Corresponding Author:

Ban Hong (Phylice) Lim, Department of Psychology, Northern Illinois University, Psychology-

Computer Science Building, DeKalb, IL 60115, USA

Email: blim1@niu.edu

Self-Worth as a Mediator

Between Attachment and

Posttraumatic Stress in

Interpersonal Trauma

Ban Hong (Phylice) Lim, BA,

1

Lauren A. Adams, BA,

1

and

Michelle M. Lilly, PhD

1

Abstract

It is well documented that most trauma survivors recover from adversity

and only a number of them go on to develop posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD). In addition, survivors of interpersonal trauma (IPT) appear to be at

heightened risk for developing PTSD in comparison to survivors of nonin-

terpersonal trauma (NIPT). Despite a robust association between IPT expo-

sure and attachment disruptions, there is a dearth of research examining the

role of attachment-related processes implicated in predicting PTSD. Using a

sample of college undergraduates exposed to IPT and NIPT, this study ex-

plores the mediating effect of self-worth in the relationship between attach-

ment and PTSD. It is hypothesized that insecure attachment will be related

to posttraumatic symptomatology via a reduced sense of self-worth in IPT

survivors but not in NIPT survivors. Mediation analyses provide support for

this hypothesis, suggesting the importance of considering negative cogni-

tions about the self in therapeutic interventions, particularly those offered

to IPT survivors.

Keywords

interpersonal trauma, attachment, self-worth, posttraumatic stress disorder

Article

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2040 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

An overwhelming majority of individuals (40% to 90%) have experienced at

least one traumatic event in their lifetime (Breslau, Davis, Andreski, & Peterson,

1991; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995; Norris, 1992; Resnick,

Kilpatrick, Dansky, Saunders, & Best, 1993). However, the lifetime prevalence

for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been estimated to be as low as

7.8% but in some cases up to 20% (Breslau et al., 1991; Kessler et al., 1995;

Perkonigg, Kessler, Storz, & Wittchen, 2000). Furthermore, although noninter-

personal traumatic events (NIPT; 33.3%), such as natural disasters and motor

vehicle accidents, have been shown to be much more prevalent than interper-

sonal traumatic events (IPT), such as physical assault and sexual assault

(10.28% and 14.32% respectively; Resnick et al., 1993), IPT survivors appear

to be more at risk than NIPT survivors for developing posttrauma psychopa-

thology, including PTSD (Breslau et al., 1991). Specifically, Resnick et al.

found the lifetime prevalence of PTSD to be significantly higher in the after-

math of IPT (38.5%) than that of NIPT (9.4%). A meta-analysis revealed that

IPT, when broken down into different types, was more related to PTSD if it

was found in a noncombat scenario, such as domestic violence and sexual

assault, rather than situations associated with combative trauma exposure

(Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003). Collectively, these findings suggest

that although differences in trauma exposure account for some variability in

posttrauma functioning, there are likely individual differences that have an

impact on the development of posttrauma psychopathology.

One vulnerability factor that has often been explored in relation to trauma

exposure and PTSD is attachment. Bowlbys attachment theory underscores

the importance of healthy infantcaregiver bonds in an individuals develop-

ment in the areas of emotion regulation, cognition, behavior, and personality,

which in turn has a strong influence on ones long-term psychological well-

being (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). Attachment theorists (e.g., Ainsworth, Blehar,

Waters, & Wall, 1978; Bowlby, 1969/1982; Hazan & Shaver, 1987) have dis-

tinguished between secure and insecure styles of attachment. Secure individu-

als tend to display a positive regard for oneself and others and are comfortable

with both intimacy and autonomy; individuals with an insecure style marked

by anxious attachment tend to view themselves and others negatively, fear

abandonment, and seek heightened intimacy in close relationships; individu-

als with avoidant attachment tend to be uncomfortable with closeness and

dependency on others and prefer to be self-reliant (Ainsworth et al., 1978).

Attachment is likely to be most germane to posttrauma functioning in cases of

IPT because exposure to IPT tends to implicate attachment processes and

affect an individuals internal working models of perceptions about self and

others (Cicchetti & Toth, 1995; Cole & Putnam, 1992). For example, betrayal

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2041

trauma, which is defined as trauma that is inflicted by caregivers or intimate

partners, entails a violation of trust by someone the survivor relies on for sur-

vival (Freyd, 1994) and is highly associated with insecure attachment (e.g.,

Cook et al., 2005).

Research has established a robust relationship between IPT (in both child-

hood and adulthood) and attachment disruptions (Alexander, 1993; Muller,

Sicoli, & Lemieux, 2000; Roche, Runtz, & Hunter, 1999; Sullivan-Hanson,

1990). Studies on childhood maltreatment showed that between 70% and

100% of survivors are insecure, which is in stark contrast to findings by other

studies, that there are only approximately 30% insecure individuals in nona-

bused samples (Carlson, Cicchetti, Barnett, & Braunwald, 1989; Cicchetti,

Cummings, Greenberg, & Marvin, 1990). Crittenden (1997) proposed that

growing up in an inconsistent or abusive environment may lead insecure

individuals to concentrate on pleasing others, thus leaving little time and

energy for self-enhancement. As a result, abuse survivors have frequently

been observed to suffer from an impaired sense of self and concurrent inabil-

ity to relate to others, which are related to attachment processes (Briere &

Elliott, 1994; Gold, Sinclair, & Bulge, 1999). Likewise, emerging research

on adulthood IPT revealed that battered women are not only at increased risks

for developing an impaired attachment compared to nonexposed women but

are also more likely to form insecure attachment to their infants during preg-

nancy (Huth-Bocks, Levendosky, Theran, & Bogat, 2004).

Despite an increasing focus on attachment in IPT survivors, the role of

attachment and related underlying processes implicated in predicting PTSD

has been underinvestigated. Research has established that attachment disrup-

tions contribute to the onset and maintenance of PTSD (MacDonald et al.,

2008; Stovall-McClough & Cloitre, 2006); thus, factors that explain the link

between attachment disruptions and PTSD deserve empirical exploration.

Self-worth may well account for this link given that it is highly associated

with both insecure attachment (e.g., OConnor & Elklit, 2008) and the onset

of PTSD (e.g., Bradley, Schwartz, & Kaslow, 2005). Broadly speaking,

self-worth refers to the satisfaction and acceptance of oneself in regards to

achievements and personal characteristics. Given the substantial impact of

early infantcaregiver interactions on the formation of mental representations

of self, attachment is critical in the development of self-worth (Collins &

Read, 1990; Feeney & Noller, 1990; Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994).

Specifically, secure individuals tend to exhibit higher self-worth that is inter-

nalized and not sought through others acceptance and approval; in contrast,

insecure individuals, particularly those with a fearful or preoccupied

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2042 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

attachment style, tend to exhibit lower self-worth that is based on ongoing

external validation (Bartholomew, 1990).

There is ample evidence documenting the implication of self-worth in the

etiology of a broad range of psychopathology, including depression and vari-

ous types of anxiety disorders (e.g., Roberts, Gotlib, & Kassel, 1996; van

Oppen & Arntz, 1994). Furthermore, greater self-worth has also been found

to be vital for adaptive posttrauma functioning. For example, research has

consistently revealed that anxious, fearful, and preoccupied attachment

styles, all of which reflect a negative self-regard, were most related to

posttraumatic stress symptomatology (Browne & Winkelman, 2007;

Muller et al., 2000). Conversely, secure and dismissing attachments, which

reflect a positive view of self, were not connected to posttraumatic stress

symptoms (Mikulincer, Florian, & Weller, 1993). IPT survivors with low

self-worth may be predisposed to experience trauma-specific guilt and

shame, which have been found to hamper trauma-related coping and place

individuals at risk for the development of PTSD (Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Foa,

Steketee, & Rothbaum, 1989; Owens & Chard, 2001). Possessing low self-

worth may also hinder ones ability to cope effectively and regulate affective

responses, which is a key marker of PTSD (Bradley et al., 2005; Sandberg,

Suess, & Heaton, 2010). Being unable to process trauma-related information

adaptively would lead trauma survivors to falsely perceive internal and exter-

nal stimuli as ongoing threats (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). In addition, positive

regard for self, as typically displayed by secure individuals, may also allow

for more tolerance of adversity and a greater sense of efficacy to mobilize and

benefit from the use of internal and external supports posttrauma (Benight &

Bandura, 2004; OConnor & Elklit, 2008).

Taken together, insecure attachment may likely contribute to posttrau-

matic stress via lowered self-worth (Sandberg et al., 2010). The current

study extends previous research by investigating the role of self-worth in the

relationship between attachment and PTSD, particularly in regard to differ-

ent types of trauma exposure (i.e., IPT and NIPT). The main hypotheses are

as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Consistent with previous studies, greater attachment

anxiety and avoidance will be related to both lowered self-worth

and heightened PTSD symptoms. Self-worth will also be inversely

correlated with PTSD symptoms.

Hypothesis 2: There will be significant differences between individuals who

experienced IPT and those who did not, in terms of attachment, self-

worth, and PTSD symptom severity. More specifically, the IPT group

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2043

will report greater overall attachment difficulties, lower self-worth, and

greater PTSD symptom severity, compared to the NIPT group.

Hypothesis 3: Self-worth will mediate the relationship between attach-

ment and PTSD for the IPT group. However, self-worth will not

mediate the relationship between attachment and PTSD for the

NIPT group.

As such, we propose a moderated mediation relationship may exist. It is

important to note that, depending on the theory being tested, a variable can be

introduced as a mediator or a moderator. In this case, self-worth is proposed as

a mediator because research has consistently shown a strong relationship

between insecure attachment and PTSD; therefore, a mediator can serve to

clarify the mechanisms behind this relationship (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004).

Method

Participants

The present study is part of a larger data set collected at a Midwestern university,

comprising a sample of 616 undergraduate students. Participants included in the

present study endorsed at least one incident of trauma in their life and had com-

plete data for the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany, 2004).

In addition, participants were chosen if they could identify and report on a trau-

matic event that was the worst or stuck with them on the Posttraumatic

Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa, 1995). All other participants were excluded.

The final sample of 228 undergraduate students had a mean age of 19.64 (SD =

3.09), and 66.7% of participants identified as female (n = 152). Most participants

were European American (68.9%, n = 157), 11.0% were African American (n =

25), 5.7% were Hispanic (n = 13), 3.5% were Asian (n = 8), and the remaining

11% identified as biracial or Other (n = 23); in some cases, the participants did

not identify their ethnicity (n = 2). The sample was comprised of mostly fresh-

men (58.3%, n = 133) and sophomores (23.7%, n = 54).

Procedure

Participants were recruited from the introductory psychology subject pool

and received class credit for their participation. Once participants signed up

for the study, they were emailed a unique login name and password as well

as a link to the questionnaires. Participants completed an informed consent

form and a battery of questionnaires online, which took about 60 min to

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2044 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

complete. A debriefing form along with resources and referrals were pro-

vided at the end of the study.

At the conclusion of the study, two trauma exposure groups were created

based on participants responses to the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire

(TLEQ; Kubany, 2004). An interpersonal trauma score was created that

summed participants exposure to the interpersonal trauma items on the TLEQ.

Participants who had a score of zero were placed in the noninterpersonal

trauma (NIPT) group, and participants with nonzero scores were placed in the

interpersonal trauma group (IPT). The groups did not differ in regards to age,

t(226) = 1.86, p = .07; gender,

2

= .46, p = .50; ethnicity,

2

= 7.86, p = .35;

or year in school,

2

= 7.70, p = .26.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire. Participants were asked a number of questions

focusing on demographics, including age, gender, ethnicity, education level,

sexual orientation, current relationship status, and household/family and per-

sonal income.

Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised Inventory (ECR-R). The ECR-R

(Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000) is a self-report questionnaire that measures

attachment difficulties, specifically attachment avoidance and attachment

anxiety. Each of the 36 items was scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1

(not at all) to 7 (extremely). For instance, the item, I worry that others wont

care about me as much as I care about them, reflects attachment anxiety,

whereas the item, I try to avoid getting too close to others, reflects attach-

ment avoidance. Respondents rate each item on the extent to which they

agree with each statement about their feelings toward close relationships. The

subscales are created by averaging the responses to the 13 items on each

subscale. A higher total score on each subscale indicates higher attachment

insecurity. Missing scores on several items of the subscales were present for

three participants and were in no particular pattern. These values were

replaced by the series mean. Research using the ECR-R has shown strong

psychometric properties, including strong internal consistency ( = .93 for

avoidance, and = .92 for anxiety), acceptable testretest reliability, and

strong validity across various populations (Fairchild & Finney, 2006; Sibley,

Fischer, & Liu, 2005). Internal consistency in the present study was = .93

for anxiety scale, and = .94 for the avoidance scale.

The World Assumption Scale (WAS). The WAS (Janoff-Bulman, 1989)

assesses cognitive schemas about self and others. There are a total of 32 items

that can be divided into subscales that assess benevolence of the world,

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2045

benevolence of people, justice, controllability, randomness, self-worth, self-

controllability, and luck. For the purposes of the present study, only the Self-

Worth subscale was used by reverse scoring specified items and summing the

responses to represent participants assumptions regarding self-worth. Items

on the Self-Worth subscale include, I am very satisfied with the kind of person

I am, and I often think I am no good at all (reverse coded). Responses are

based on how much the respondent agrees with each statement on a scale of

1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), with a higher score indicating

more positive assumptions. Two participants had missing values on several

items of the Self-Worth subscale, which were replaced by the series mean.

Discriminant analyses conducted in the development of the measure revealed

that three of the assumptions, including self-worth (Wilkss = .98), were

able to discriminate between survivors and nonsurvivors of trauma (Janoff-

Bulman, 1992). Internal consistency for the Self-Worth subscale was accept-

able ( = .73) in the present study.

Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale. The PDS (Foa, 1995) measures

the severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms in the previous month.

Respondents are asked to identify a traumatic event that was the worst

or stuck with them and answer a series of questions pertaining to that

event that measure PTSD diagnostic criteria. It also assesses the extent

to which symptoms have interfered with various areas of the respon-

dents life. For the present study, a total symptom severity score, rang-

ing from 0 to 51, was generated by summing the items on the symptom

clusters (i.e., hyperarousal, reexperiencing, and avoidance). Symptom

severity was rated as follows: 0 = no rating, 1 to 10 = mild, 11 to 20 =

moderate, 21 to 35 = moderate to severe, and 36 and above = severe. The

scale has demonstrated good reliability for the symptom severity scale

( = .92) and good testretest reliability (r = .83; Foa, 1995). For the

present study, internal consistency for the PTSD symptom severity scale

was high ( = .92).

Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. The TLEQ (Kubany, 2004) assesses

exposure to potentially traumatic events and how many times each of these

events has happened. The types of trauma assessed include natural disaster,

sexual assault, physical abuse, war or combat exposure, and motor vehicle

accidents. Each of the 23 items was rated based on the following responses:

never, once, twice, 3 times, 4 times, and more than 5 times. The TLEQ yields a

total trauma history score by tallying the items, with higher scores indicating

greater traumatic event exposure. Scores for both IPT and NIPT were gener-

ated. The IPT score was created by summing the items associated with sex-

ual assault, nonsexual assault (e.g., physical assault, being robbed), or

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2046 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

stalking; the NIPT score summed responses to items associated with acci-

dents, natural disasters, war or combat exposure, death or illness of a loved

one, miscarriage or abortion. Given that civilian or everyday traumas are of

interest in this study and that the intent and dynamics of military-related

trauma are very different from civilian trauma and may be differentially

related to attachment and self-worth, we decided to categorize military-

related trauma as an NIPT. Likewise, Ozer et al. (2003) confirmed that

noncombat IPT items, such as domestic violence and sexual assault, were

more related to PTSD compared to that of combative trauma exposure. The

TLEQ has demonstrated high testretest reliability as well as high conver-

gent validity with other measures of posttraumatic stress disorder such as

structured interviews (Kubany et al., 2000).

Results

Participants in the present study reported exposure to an average of 7.55 (SD =

8.09) total traumatic events, which indicates the total number of times each

trauma occurred; thus, this number could include multiple exposures to the

same type of event. In total, participants endorsed exposure to an average of

5.05 (SD = 2.90) of the 23 different types of events assessed on the TLEQ,

which ranged between exposure to only one type of trauma and exposure to

all of the 23 different types of trauma. Table 1 shows the percentage of par-

ticipants who reported at least one exposure to each type of traumatic event

assessed on the TLEQ. Chi-square analyses indicated no gender differences

in exposure to the traumatic events, with the exception of being robbed,

military combat, and exposure to anothers death. Men were overrepre-

sented in the robbed,

2

(1) = 8.14, p = .004, and military combat exposure

group,

2

(1) = 5.01, p = .03, whereas women were overrepresented in the

exposure to anothers death group,

2

(1) = 6.13, p = .01. In regards to IPT,

participants reported exposure to an average of 3.73 total events (SD =

6.24) and an average of 2.69 (SD = 2.11) different types of interpersonal

traumatic events. The mean severity score in regards to PTSD symptoms was

9.43 (SD = 10.45) and ranged between 0 and 48. Using a cutoff score of 28

to suggest diagnostic levels of PTSD symptoms (Coffey, Dansky, Falsetti,

Saladin, & Brady, 1998), 8.8% of the sample (n = 20) achieved a symptom

severity level that may qualify for a PTSD diagnosis. This number is slightly

higher than levels of PTSD reported in the general populations (7.8%;

Kessler et al., 1995). Of the 20 individuals who qualify for a PTSD diagno-

sis, 16 were female. However, a chi-square statistic revealed that this did not

constitute statistically significant overrepresentation by women,

2

(1) = 1.75,

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2047

p = .19. In regard to attachment, the mean attachment scores for Anxiety and

Avoidance subscales were as follows: attachment avoidance (M = 2.94, SD =

1.18), attachment anxiety (M = 3.39, SD = 1.27). Participant scores on the

WAS Self-Worth subscale had a mean of 17.95 (SD = 4.12). The attachment

and self-worth scores were comparable to those reported for other college

undergraduates who had been previously exposed to traumatic events (Lilly,

2011; Sandberg et al., 2010).

A correlation matrix of the variables of interest is presented in Table 2.

Consistent with the first hypothesis, attachment difficulties were significantly

inversely related to self-worth and positively related to PTSD symptom

severity. As hypothesized, self-worth was significantly inversely related to

PTSD symptom severity. Hypotheses related to interpersonal trauma expo-

sure were partially confirmed. Although interpersonal trauma exposure was

significantly positively related to both PTSD symptom severity and attachment

avoidance, it was not significantly related to attachment anxiety or self-worth.

In addition, although noninterpersonal trauma exposure was significantly pos-

itively related to PTSD symptom severity, it was not related to attachment

difficulties or self-worth. This provides preliminary support for our main

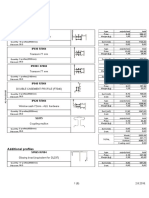

Table 1. Prevalence of Traumatic Events With Chi-Square to Gender Differences

Interpersonal Trauma %

2

Noninterpersonal Trauma %

2

Adolescent CSA 12.3 3.44 Abortion 6.1 0.04

CSA by peer 9.2 .94 Accident, fire, explosion 16.2 1.03

CSA by older person 12.3 2.04 Life-threatening illness 8.3 0.03

CPA 15.4 2.70 Others death 66.2 6.13*

Experienced IPV 16.7 1.01 Others illnesses/trauma 53.5 0.22

Harassment 5.7 0.06 Other traumatic event 18.0 1.49

Robbed 7.5 8.14** Military combat 2.2 5.01*

Physical assault by

stranger

8.3 1.84 Miscarriage 4.4 0.84

Sexual assault 9.2 3.78 Motor vehicle accident 18.0 3.81

Stalked 18.0 0.95 Natural disaster 43.0 0.01

Threatened 26.8 2.20 Witnessed stranger

physical assault

9.2 0.94

Witnessed family

violence

26.3 0.10

Note: N = 228.

*p < .05. **p < .01

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2048 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

hypothesis that self-worth will mediate the relationship between attachment

and PTSD for the IPT group; however, self-worth will not mediate the rela-

tionship between attachment and PTSD for the NIPT group.

The second set of hypotheses proposed that there would be significant dif-

ferences between the IPT and NIPT group, with the IPT group reporting

greater overall attachment difficulties, lower self-worth, and greater PTSD

symptom severity. Independent samples t test were conducted and are sum-

marized in Table 3. As hypothesized, significant differences were observed

between the IPT and the NIPT groups on attachment difficulties, self-worth,

and PTSD symptom severity. Individuals in the IPT group reported overall

greater attachment avoidance and anxiety, as well as greater PTSD symptom

severity, whereas individuals in the NIPT group reported significantly greater

self-worth, with small to moderate size effects.

Next, we aimed to examine whether self-worth mediated the relationship

between attachment difficulties and PTSD symptom severity. We proposed

that self-worth would mediate the relationship between attachment difficul-

ties and PTSD symptom severity for those in the IPT group but would not

mediate the relationship for those in the NIPT group. As such, we proposed

that a moderated mediation relationship may exist.

According to Frazier et al., four statistical conditions need to be fulfilled

to establish a mediation effect: (a) The predictor variable is significantly

related to the criterion variable, (b) the predictor variable is related to the

mediator variable, (c) the mediator variable is related to the criterion variable

when controlling for the effects of the predictor variable on the criterion vari-

able, and (d) inclusion of the mediator variable in the model must significantly

reduce the magnitude of the relationship between the predictor variable and the

criterion variable. A complete mediation is observed when this relationship is

Table 2. Correlation Matrix Between Primary Variables of Interest

1 2 3 4 5 6

1. Self-worth

2. Attachment anxiety .56***

3. Attachment avoidance .40*** .61***

4. Posttraumatic stress symptom severity .30*** .29*** .20**

5. Interpersonal trauma exposure .11 .06 .18** .18**

6. Noninterpersonal trauma exposure .00 .00 .06 .13* .38**

Note: N = 228.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2049

reduced to zero; otherwise, the relationship between the predictor variable

and criterion variable is partially mediated, which is more prevalent (for fur-

ther discussion on mediation and the distinction between mediation and mod-

eration, see Frazier et al., 2004).

Prior to running the regression analyses, the interrelationships between

demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, income, race, and relationship sta-

tus) and outcome variables in each step of the regression analyses were

examined. Given that none of the demographic variables was significantly

related to self-worth or posttraumatic stress symptomatology, no covariate

variables were included in subsequent regression analyses. Using the proce-

dures outlined in Frazier et al. (2004), we conducted a series of regression

analyses, the results of which are shown in Table 5 (attachment avoidance as

predictor) and Table 5 (attachment anxiety as predictor). First, we aimed to

determine whether self-worth mediated the relationship between attachment

avoidance and PTSD symptom severity for individuals in the IPT group but not

the NIPT group. In the first step, PTSD symptom severity was significantly

related to attachment avoidance only in the IPT group ( = 1.63, p = .02) and

not in the NIPT group ( = 1.73, p = .10). Given the lack of a significant

relationship between the predictor variable and criterion variable for the

NIPT group, it was determined that self-worth could not mediate the relation-

ship between attachment avoidance and PTSD symptom severity. As such,

the remaining analyses were only completed for the IPT group. Proceeding

with the mediation, self-worth and attachment avoidance were significantly

positively related ( = 1.34, p < .001) to the IPT group. In the final step,

PTSD symptom severity was regressed on both self-worth and attachment

avoidance. Consistent with the presence of a partial mediation relationship, it

Table 3. Comparisons Between Survivors of Interpersonal Trauma (IPT) and

Survivors of Noninterpersonal Trauma (NIPT) on Primary Variables of Interest

IPT Group NIPT Group

M (SD) M (SD) t p Cohens d

Attachment anxiety 3.53 (1.32) 3.16 (1.15) 2.10 .04* .29

Attachment avoidance 3.05 (1.25) 2.73 (1.02) 1.99 .05* .28

Self-worth 17.50 (4.33) 18.73 (3.62) 2.30 .02* .31

Posttraumatic stress

severity

10.63 (10.69) 7.34 (9.73) 2.31 .02* .32

*p < .05. **p < .01.

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2050 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

was found that the mediator of self-worth was significantly related to PTSD

symptom severity ( = .65, p = .003) and that attachment avoidance no lon-

ger predicted PTSD symptom severity ( = .76, p = .31) (see fig. 1). A Sobel

test was conducted to examine the significance of the partial mediation,

which revealed a z score of 2.63 (p = .009).

The same procedures were adopted to determine whether self-worth medi-

ated the relationship between attachment anxiety and PTSD symptom sever-

ity for the IPT group but not the NIPT group. Unlike for attachment avoidance,

attachment anxiety was significantly related to PTSD symptom severity for

both the IPT ( = 2.16, p = .001) and the NIPT ( = 2.40, p = .009) groups.

Similar results were observed in the second step, as attachment anxiety was

significantly related to self-worth for both the IPT ( = 1.95, p <.001) and

NIPT ( = 1.40, p < .001) groups. However, the regression models diverged

in the third step. For the IPT group, a partial mediation model was suggested,

as attachment anxiety no longer predicted PTSD symptom severity ( = 1.13,

p = .16) whereas self-worth was significantly related to PTSD symptom

Table 4. Linear Regression Analyses Testing Self-Worth as a Mediator of the

Relationship Between Attachment Avoidance and Posttraumatic Stress

Interpersonal Trauma

(IPT) or Noninterpersonal

Trauma (NIPT)

Adj. R

2

B (SE B) Sig.

IPT NIPT IPT NIPT IPT NIPT

Regression 1

Outcome: Posttraumatic

stress

.03 .02

Predictor: Attachment

avoidance

1.63 (.71) 1.73 (1.05) .02* .101

Regression 2

Outcome: Self-worth .14

Predictor: Attachment

avoidance

1.34 (.27) .000***

Regression 3

Outcome: Posttraumatic

stress

.08

Mediator: Self-worth .65 (.21) .003**

Predictor: Attachment

avoidance

.76 (.74) .31

Note: N = 228.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2051

severity ( = .53, p = .03). A Sobel test of significance revealed a z score of

2.14 (p = .03), suggesting that self-worth significantly, partially mediated the

relationship between attachment anxiety and PTSD symptom severity for the

IPT group (see fig. 2). Consistent with the study hypotheses, a mediation

Table 5. Linear Regression Analyses Testing Self-Worth as a Mediator of the

Relationship Between Attachment Anxiety and Posttraumatic Stress

Interpersonal

Trauma (IPT) or

Noninterpersonal

Trauma (NIPT)

Adj. R

2

B (SE B) Sig.

IPT NIPT IPT NIPT IPT NIPT

Regression 1

Outcome:

Posttraumatic stress

.06 .07

Predictor: Attachment

anxiety

2.16 (.65) 2.40 (0.899) .001** .009***

Regression 2

Outcome: Self-worth .35 .19

Predictor: Attachment

anxiety

1.95 (.22) 1.40 (0.31) .000*** .000***

Regression 3

Outcome:

Posttraumatic stress

.09 .08

Mediator: Self-worth 0.53 (.24) .42 (0.32) .03* .19

Predictor: Attachment

anxiety

1.13 (.80) 1.81 (1.00) .16 .07

Note: N = 228.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Figure 1. Self-worth as a mediator of the relationship between attachment

avoidance and posttraumatic stress for individuals exposed to interpersonal trauma

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2052 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

model was not observed for the NIPT group, as neither attachment anxiety (

= 1.81, p = .07) nor self-worth ( = .42, p = .19) were significantly related

to PTSD symptom severity in the final regression.

Discussion

Early experiences with caregivers have repeatedly been shown to bear pro-

found influences on mental health well-being. Indeed, many studies have

demonstrated the implication of attachment in a myriad of psychological

disorders, including depression, anxiety disorder, and PTSD (e.g., Bifulco,

Moran, Ball, & Lillie, 2002; OConnor & Eklit, 2008; van Buren & Cooley,

2002). Nevertheless, the mechanisms through which attachment difficulties

lead to heightened risk of developing PTSD have remained relatively

unknown. More effort is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the

attachmentPTSD relationship to improve related therapeutic interventions,

as suggested by Sandberg et al. (2010). Correspondingly, the present study

sought to investigate the role of self-worth in the relationship between

attachment and PTSD, particularly in regard to different types of trauma

exposure (i.e., IPT and NIPT).

Consistent with previous research, findings in the current study revealed

that insecure attachment was inversely related to self-worth (e.g., OConnor

& Elklit, 2008) and positively related to PTSD symptom severity (e.g.,

Bradley et al., 2005). Self-worth was also significantly inversely related to

PTSD symptom severity. These findings provide preliminary support for the

proposed mediationthat self-worth will mediate the relationship between

attachment and PTSD. However, although IPT exposure was significantly

positively related to both PTSD symptom severity and attachment avoidance,

it was not significantly related to attachment anxiety or self-worth. This

Figure 2. Self-worth as a mediator of the relationship between attachment anxiety

and posttraumatic stress for individuals exposed to interpersonal trauma

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2053

finding is contrary to previous research that had shown attachment anxiety to

be more associated with IPT and that attachment avoidance was more strongly

related to NIPT. In particular, Elwood and Williams (2007) observed that IPT

survivors tend to display greater attachment anxietybut not more avoid-

ancecompared to individuals who did not endorse IPT. Renaud (2008) also

suggested that attachment avoidance, relative to attachment anxiety, may be

more related to PTSD following NIPT such as combat exposure, likely

because attachment avoidance is more pertinent to perceptions of external

threat rather than perceptions of self (e.g., self-worth). One explanation for

our finding is related to the composition of the IPT group in the current study;

individuals in the IPT group may also have been exposed to NIPT, as the

analyses indicate a positive, significant correlation between IPT and NIPT

(see Table 2). Alternatively, attachment avoidance, which involves distancing

oneself from aversive emotions, may also serve as a self-protective adapta-

tion in the face of trauma (Sandberg et al., 2010). Nevertheless, these contra-

dictory findings merit further investigation to clarify whether attachment

anxiety and attachment avoidance indeed lead to differential outcomes in

response to varying types of trauma exposure.

Consistent with both betrayal trauma theory (Freyd, 2009) and world

assumptive theory (Janoff-Bulman, 1992), the IPT and NIPT groups were

found to differ significantly on their attachment, self-worth, and PTSD symp-

tom severity. In contrast to the NIPT group individuals, who reported greater

self-worth, individuals in the IPT group reported greater attachment avoid-

ance, attachment anxiety, and PTSD symptom severity, and thus, appeared to

be less adaptive . These findings are consistent with past research suggesting

that IPT exposure typically leads to heightened psychological distress (Freyd,

2009; Janoff-Bulman, 1992). More specifically, because IPT is frequently

inflicted by someone the survivor trusts or relies on for survival (e.g., care-

giver or intimate partners), individuals exposed to IPT are likely to be less

adaptive in the face of trauma (Freyd, 2009). Likewise, Janoff-Bulman pro-

posed that IPT may be more detrimental to our core conceptual system and

may subsequently lead to poor posttrauma functioning. Indeed, being harmed

by another person can result in humiliation, questions of personal autonomy

and strength of will, as well as shattering of self-worth. Furthermore, because

NIPT such as exposure to natural disasters is usually considered an unfortu-

nate event and not a result of ones own doing, NIPT survivors typically

receive greater support and validation from others (Janoff-Bulman, 1992).

Findings in the current study provide support for the hypothesized moder-

ated mediation. As hypothesized, self-worth mediated the relationship

between attachment and PTSD in survivors exposed to IPT, but the mediating

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2054 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

effect was not observed in survivors exposed to NIPT. Consistent with previ-

ous research, insecure attachment may lead IPT survivors to believe that they

are accountable for the occurrence of the traumatic event. These individuals

are also likely to engage in characterological self-blame and attribute the

occurrence of trauma to some enduring, negative self-trait, which in turn

results in diminished self-worth and increased risk for developing PTSD

(Foa, Feske, Murdock, Kozak, & McCarthy, 1991; Silver, Boon, & Stones,

1983). Insecure individuals may also be inclined to rely heavily on affect,

rather than cognition, in directing their behaviors and have a highly sensitive

emotional system (Crittenden, 1997). Their inability to process trauma-

related information adaptively may in turn cause them to falsely perceive

internal and external stimuli as ongoing threats, which is a prominent symp-

tom of PTSD (Ehlers & Clark, 2000).

Self-worth has also been associated with a greater sense of efficacy to

mobilize resources for effective trauma-related coping (Benight & Bandura,

2004; Bradley et al., 2005). For that reason, secure individuals may be more

likely than insecure individuals to seek social support following trauma,

which has been shown to alleviate adverse effects on self-worth and thwart

the development of PTSD (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Cuneo &

Schiaffino, 2002; Ozer et al., 2003). In addition, self-worth has also been

found to be implicated in dissociation (Lilly, 2011), which often co-occurs

with PTSD following trauma. More specifically, Lilly proposed that dissocia-

tion may be used as a tactic in traumatic situations to defend against strong

threats to ones sense of self-worth. As observed in trauma survivors with

PTSD, dissociative symptoms may also likely arise from feelings of being

damaged or trauma-related guilt.

Several limitations in the present study need to be addressed in future

studies. First, the use of a cross-sectional design in the present study makes it

difficult to determine the direction of causality. Although the current study

modeled insecure attachment and diminished self-worth as precursors of

posttraumatic stress symptoms, it is possible that insecure attachment and

diminished self-worth are instead outcomes of posttraumatic stress symp-

toms. Further studies using a longitudinal design that assess attachment and

self-worth prior to and following a traumatic event are warranted to examine

this relationship further. Second, it is important to distinguish exposure to

childhood from later IPT in future studies, considering that attachment style

and self-worth are developmental variables, and thus, may be more related to

childhood trauma. Third, the use of a convenient college sample poses chal-

lenges in generalizing the current findings to a wider range of trauma survi-

vors. A sample of college students who are exposed to trauma may be

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2055

unrepresentative of trauma survivors at large because being able to attend

college may be indicative of a relatively better psychological adjustment

or having experienced less trauma, compared to other trauma survivors in

clinical setting, in the community, or who dropped out of college following

trauma. Fourth, self-selection bias could also influence the composition of

the sample in this study. Participants were given a number of options for

research studies in which to participate, and those who chose to participate in

this study may represent a skewed sample of trauma survivors. In particular,

individuals who have been exposed to severe or chronic traumatic events

may likely avoid participating in trauma-related studies. Fifth, to generate a

more holistic and accurate understanding of posttrauma functioning, it may

be necessary to take into account all possible adverse mental health outcomes

associated with trauma exposure. Sixth, it is difficult to gauge clinical signifi-

cance of the outcome variables because the measures we used do not provide

such information. For example, although there is some evidence that a cutoff

score of 28 on the PDS (Coffey et al., 1998) may reflect the potential pres-

ence of a PTSD diagnosis, there are no norms for scores on the PDS that

suggest clinically meaningful differences. Lastly, the use of self-reports may

also introduce recall bias and socially desirable responding.

Despite these limitations, the study represents an important contribution to

the field of trauma recovery and mental health. Research has shown that inse-

cure attachment is a risk factor in developing emotional difficulties following

trauma. It is important to clarify this link between attachment and PTSD

because attachment denotes a more enduring, distal factor that may be resis-

tant to change. More important, a better understanding of the underlying eti-

ology contributing to this association, which in this case implicates a negative

working model of the self, can help design and tailor prevention and interven-

tion strategies offered to trauma survivors.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publica-

tion of this article.

References

Ainsworth, M. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment:

A psychological study of the strange situation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2056 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

Alexander, P. C. (1993). The differential effects of abuse characteristics and attach-

ment in the prediction of long-term effects of sexual abuse. Journal of Interper-

sonal Violence, 8, 346-362. doi:10.1177/088626093008003004

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal

of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147-178. doi:10.1177/0265407590072001

Benight, C. C., & Bandura, A. (2004). Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recov-

ery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behavior Research and Therapy, 42,

1129-1148. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008

Bifulco, A., Moran, P. M., Ball, C., & Lillie, A. (2002). Adult Attachment Style-II: Its

relationship to psychosocial depressive-vulnerability. Social Psychiatry and Psy-

chiatric Epidemiology, 37, 60-67. doi:10.1007/s127-002-8216-x

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss. Vol. 1: Attachment. New York, NY: Basic

Books. (Original work published 1969)

Bradley, R., Schwartz, A. C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2005). Posttraumatic stress disor-

der symptoms among low-income, African American women with a history of

intimate partner violence and suicidal behaviors: Self-esteem, social support,

and religious coping. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18, 685-696. doi:10.1002/

jts.20077

Breslau, N., Davis, G. C., Andreski, P., & Peterson, E. (1991). Traumatic events and

posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of

General Psychiatry, 48, 216-222. Retrieved from http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors

for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 5, 748-766. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.68.5.748

Briere, J. N., & Elliott, D. M. (1994). Immediate and long-term impacts of child sexual

abuse. Future of Children, 4, 54-69. doi:10.2307/1602523

Browne, C., & Winkelman, C. (2007). The effect of childhood trauma on later

psychological adjustment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 684-697.

doi:10.1177/0886260507300207

Carlson, V., Cicchetti, D., Barnett, D., & Braunwald, K. (1989). Disorganized/disoriented

attachment relationships in maltreated infants. Developmental Psychology, 24, 525-531.

Cicchetti, D., Cummings, E. M., Greenberg, M. T., & Marvin, R. S. (1990). An orga-

nizational perspective on attachment beyond infancy: Implications for theory,

measurement, and research. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings

(Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research and intervention (pp.

3-49). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (1995). Child maltreatment and attachment organization:

Implications for intervention. In S. Goldberg, R. Muir, & J. Kerr (Eds.), Attachment

theory: Social, developmental, and clinical perspectives (pp. 279-308). Hillsdale,

NJ: Analytic Press.

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2057

Coffey, S. F., Dansky, B. S., Falsetti, S. A., Saladin, M. E., & Brady, K. T. (1998).

Screening for PTSD in a substance abuse sample: Psychometric properties of a

modified version of the PTSD Symptom Scale Self-Report. Journal of Traumatic

Stress, 11, 393-399. doi:10.1023/A:1024467507565

Cole, P. M., & Putnam, F. W. (1992). Effect of incest on self and social functioning:

A developmental psychopathology perspective. Journal of Consulting and Clini-

cal Psychology, 60, 174-184. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.60.2.174

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relation-

ship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58,

644-663. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644

Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M., Cloitre, M., . . . van der

Kolk, B. (2005). Complex trauma in children and adolescence. Psychiatric Annals,

35, 390-398. Retrieved from http://www.psychiatricannalsonline.com/

Crittenden, P. M. (1997). Patterns of attachment and sexual behavior: Risk of dys-

function versus opportunity for creative integration. In L. Atkinson & J. Zucker

(Eds.), Attachment and psychopathology (pp. 47-93). New York, NY: Guilford.

Cuneo, K. M., & Schiaffino, K. M. (2002). Adolescent self-perceptions of adjust-

ment to childhood arthritis: The influence of disease activity, family resources,

and parent adjustment. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 363-371. doi:10.1016/

S1054-139X(01)00324-X

Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Behavior Research and Therapy, 38, 319-345. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0

Elwood, L. S., & Williams, N. L. (2007). PTSD-related cognitions and romantic

attachment style as moderators of psychological symptoms in victims of inter-

personal trauma. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 1189-1209. doi:

10.1521/jscp.2007.26.10.1189

Fairchild, A. J., & Finney, S. J. (2006). Investigating validity evidence for the Experi-

ences in Close Relationships-Revised Questionnaire. Educational and Psycho-

logical Measurement, 66, 116-135. doi:10.1177/0013164405278564

Feeney, J. A., & Noller, P. (1990). Attachment style as a predictor of adult roman-

tic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 281-291.

doi:10.1037//0022-3514.58.2.281

Foa, E. B. (1995). Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scalemanual. Minneapolis, MN:

National Computer Systems.

Foa, E. B., Feske, U., Murdock, T. B., Kozak, M. J., & McCarthy, P. R. (1991). Pro-

cessing of threat-related information in rape victims. Journal of Abnormal Psy-

chology, 100, 156-162. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.2.156

Foa, E. B., Steketee, G., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1989). Behavioral/cognitive concep-

tualizations of post-traumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapy, 20, 155-176.

doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(89)80067-X

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2058 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

Fraley, R. C., & Shaver, P. R. (2000). Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical devel-

opments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General

Psychology, 4, 132-154. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.4.2.132

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analy-

sis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 78, 350-365. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350

Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator

effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51,

115-134. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115

Freyd, J. (1994). Betrayal trauma: Traumatic amnesia as an adaptive response to child-

hood abuse. Ethics & Behavior, 4, 307-329. doi:10.1207/s15327019eb0404_1

Freyd, J. J. (2009). What is a betrayal trauma? What is betrayal trauma theory?

Retrieved from http://dynamic.uoregon.edu/~jjf/defineBT.html

Gold, S. R., Sinclair, B. B., & Bulge, K. A. (1999). Risk of sexual revictimization:

A theoretical model. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 4, 457-470. doi:10.1016/

S1359-1789(98)00024-X

Griffin, D., & Bartholomew, K. (1994). Models of the self and other: Fundamental

dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 67, 430-445. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.430

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. doi:10.1037/0022-

3514.52.3.511

Huth-Bocks, A. C., Levendosky, A. A., Theran, S. A., & Bogat, G. A. (2004). The

impact of domestic violence on mothers prenatal representations of their infants.

Infant Mental Health Journal, 25, 79-98. doi:10.1002/imhj.10094

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1989). Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events:

Applications of the schema construct. Social Cognition, 7, 113-136. doi:10.1521/

soco.1989.7.2.113

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of

trauma. New York, NY: Free Press.

Kessler, R. C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., Hughes, M., & Nelson, C. B. (1995). Post-

traumatic stress disorder in a national comorbidity survey. Archives of General

Psychiatry, 52, 1048-1060. Retrieved from http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org

Kubany, E. S. (2004). Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ). Los Angeles,

CA: Western Psychological Services.

Kubany, E. S., Haynes, S. N., Leisen, M. B., Owens, J. A., Kaplan, A. S., Watson, S. B., &

Burns, K. (2000). Development and preliminary valiation of a brief broad-spectrum

measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychologi-

cal Assessment, 12, 210-224. doi:10.1037//1040-3590.I2.2.210

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2059

Lilly, M. M. (2011). The contributions of interpersonal trauma exposure and world

assumptions in predicting dissociation in undergraduates. Journal of Trauma &

Dissociation, 12, 375-392. doi:10.1080/15299732.2011.573761

Macdonald, H. Z., Beeghly, M., Grant-Knight, W., Augustyn, M., Woods, R. W., Carbral, H.,

. . . Frank, D. A. (2008). Longitudinal association between infant disorganized attach-

ment and childhood posttraumatic stress symptoms. Development and Psychopathol-

ogy, 20, 493-508. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000242

Mikulincer, M., Florian, V., & Weller, A. (1993). Attachment styles, coping strategies, and

posttraumatic psychological distress: The impact of the Gulf War in Israel. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 817-826. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.817

Muller, R. T., Sicoli, L. A., & Lemieux, K. E. (2000). Relationship between attach-

ment style and posttraumatic stress symptomatology among adults who report

the experience of childhood abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13, 321-332.

doi:10.1023/A:1007752719557

Norris, F. (1992). Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impact of different poten-

tially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 60, 409-418. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.60.3.409

OConnor, M., & Elklit, A. (2008). Attachment styles, traumatic events, and PTSD:

A cross-sectional investigation of adult attachment and trauma. Attachment &

Human Development, 10, 59-71. doi:10.1080/14616730701868597

Owens, G. P., & Chard, K. M. (2001). Cognitive distortions among women report-

ing childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16, 178-191.

doi:10.1177/088626001016002006

Ozer, E. J., Best, S. R., Lipsey, T. L., & Weiss, D. S. (2003). Predictors of post-

traumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological

Bulletin, 129, 52-73. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52

Perkonigg, A., Kessler, R. C., Storz, W., & Wittchen, H.-U. (2000). Traumatic events

and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: Prevalence, risk factors, and

comorbidity. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 101, 46-59. doi:10.1034/j.1600-

0447.2000.101001046.x

Renaud, E. F. (2008). The attachment characteristics of combat veterans with PTSD.

Traumatology, 14, 1-12. doi:10.1177/1534765608319085

Resnick, H. S., Kilpatrick, D. G., Dansky, B. S., Saunders, B. E., & Best, C. L. (1993).

Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative

sample of women. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 61, 984-991.

doi:10.1037//0022-006X.61.6.984

Roberts, J. E., Gotlib, I. H., & Kassel, J. D. (1996). Adult attachment security and

symptoms of depression: The mediating roles of dysfunctional attitudes and

low self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 310-320.

doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.310

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2060 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(10)

Roche, D. N., Runtz, M. G., & Hunter, M. A. (1999). Adult attachment: A mediator

between child sexual abuse and later psychological adjustment. Journal of Inter-

personal Violence, 14, 184-207. doi:10.1177/088626099014002006

Sandberg, D. A., Suess, E. A., & Heaton, J. L. (2010). Attachment anxiety as a media-

tor of the relationship between interpersonal trauma and posttraumatic symptom-

atology among college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 33-49.

doi:10.1177/0886260508329126

Sibley, C. G., Fischer, R., & Liu, J. H. (2005). Reliability and validity of the Revised

Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR-R) self-report measure of adult roman-

tic attachment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1524-1536.

doi:10.1177/0146167205276865

Silver, R. L., Boon, C., & Stones, M. H. (1983). Searching for meaning in misfortune: Mak-

ing sense of incest. Journal of Social Issues, 39, 81-101. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1983.

tb00142.x

Stovall-McClough, K. C., & Cloitre, M. (2006). Unresolved attachment, PTSD, and

dissociation in childhood abuse histories. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psy-

chology, 74, 219-228. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.219

Sullivan-Hanson, J. M. (1990). The early attachment and current affectional bonds of

battered women: Implications for the impact of spouse abuse on children (Unpub-

lished doctoral dissertation). University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

van Buren, A., & Cooley, E. L. (2002). Attachment styles, view of self and negative

affect. North American Journal of Psychology, 4, 417-430. Retrieved from http://

najp.8m.com/

van Oppen, P., & Arntz, A. (1994). Cognitive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Behavior Research and Therapy, 32, 79-87. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)90086-8

Bios

Ban Hong (Phylice) Lim is currently a second year doctoral student in the clinical

psychology program at Northern Illinois University. She earned her B.A. in

Psychology in 2010 from University of Kansas. Broadly speaking, her interests

include a) exploring factors impacting mental health sequeale following trauma, b)

examining the different types of traumatic events on mental health sequeale, c) under-

standing factors impacting the occurrences and reoccurrences of intimate partner

violence, and d) exploring how the abovementioned contextual factors facilitate or

hinder survivors recovery from the violence.

Lauren A. Adams completed her BA in psychology at Northern Illinois University

in 2011. She has completed research in the area of intimate partner violence, revic-

timization, and mental health outcomes. She completed an internship as an advocate

at a local domestic violence shelter in DeKalb, Illinois. She plans to attend graduate

school and pursue a career as a counselor.

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lim et al. 2061

Michelle M. Lilly began as an assistant professor at Northern Illinois University in

the fall of 2009. She earned her doctorate in clinical psychology and womens studies

at the University of Michigan in 2008 and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the

Psychological Clinic in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Her research has focused predomi-

nantly in the following areas: intimate partner violence, PTSD, and the mediating role

of ethnicity, coping, world assumptions, and religiosity. She has also done research in

the area of police work and the role that gender plays in predicting mental health

outcomes.

by Allan de Guzman on April 10, 2014 jiv.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Instructional Supervisory Plan BITDokument7 SeitenInstructional Supervisory Plan BITjeo nalugon100% (2)

- Ethiopia FormularyDokument543 SeitenEthiopia Formularyabrham100% (1)

- A Terence McKenna Audio Archive - Part 1Dokument203 SeitenA Terence McKenna Audio Archive - Part 1BabaYagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book - IMO Model Course 7.04 - IMO - 2012Dokument228 SeitenBook - IMO Model Course 7.04 - IMO - 2012Singgih Satrio Wibowo100% (4)

- Basilio, Paul Adrian Ventura R-123 NOVEMBER 23, 2011Dokument1 SeiteBasilio, Paul Adrian Ventura R-123 NOVEMBER 23, 2011Sealtiel1020Noch keine Bewertungen

- Test - To Kill A Mockingbird - Chapter 17 - Quizlet PDFDokument2 SeitenTest - To Kill A Mockingbird - Chapter 17 - Quizlet PDFchadlia hadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disha Publication Previous Years Problems On Current Electricity For NEET. CB1198675309 PDFDokument24 SeitenDisha Publication Previous Years Problems On Current Electricity For NEET. CB1198675309 PDFHarsh AgarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cayman Islands National Youth Policy September 2000Dokument111 SeitenCayman Islands National Youth Policy September 2000Kyler GreenwayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 9 Special Rules of Court On ADR Ver 1 PDFDokument8 SeitenChap 9 Special Rules of Court On ADR Ver 1 PDFambahomoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leseprobe Aus: "Multilingualism in The Movies" Von Lukas BleichenbacherDokument20 SeitenLeseprobe Aus: "Multilingualism in The Movies" Von Lukas BleichenbachernarrverlagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simple Past Story 1Dokument7 SeitenSimple Past Story 1Ummi Umarah50% (2)

- Chapter-British Parliamentary Debate FormatDokument8 SeitenChapter-British Parliamentary Debate FormatNoelle HarrisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building Social CapitalDokument17 SeitenBuilding Social CapitalMuhammad RonyNoch keine Bewertungen

- QUARTER 3, WEEK 9 ENGLISH Inkay - PeraltaDokument43 SeitenQUARTER 3, WEEK 9 ENGLISH Inkay - PeraltaPatrick EdrosoloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instructional MediaDokument7 SeitenInstructional MediaSakina MawardahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rules of SyllogismDokument6 SeitenRules of Syllogismassume5Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lara CroftDokument58 SeitenLara CroftMarinko Tikvicki67% (3)

- Lista Materijala WordDokument8 SeitenLista Materijala WordAdis MacanovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3a Ela Day 3Dokument5 Seiten3a Ela Day 3api-373496210Noch keine Bewertungen

- GrandEsta - Double Eyelid Surgery PDFDokument2 SeitenGrandEsta - Double Eyelid Surgery PDFaniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- t10 2010 Jun QDokument10 Seitent10 2010 Jun QAjay TakiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABHI Network List As On 30-06-2023Dokument3.401 SeitenABHI Network List As On 30-06-20233uifbcsktNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dictums of Famous ArchitectsDokument3 SeitenDictums of Famous ArchitectsErwin Ariola100% (2)

- Introducing Identity - SummaryDokument4 SeitenIntroducing Identity - SummarylkuasNoch keine Bewertungen

- If He Asked YouDokument10 SeitenIf He Asked YouLourdes MartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- gtg60 Cervicalcerclage PDFDokument21 Seitengtg60 Cervicalcerclage PDFLijoeliyas100% (1)

- Security and Azure SQL Database White PaperDokument15 SeitenSecurity and Azure SQL Database White PaperSteve SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Donchian 4 W PDFDokument33 SeitenDonchian 4 W PDFTheodoros Maragakis100% (2)

- Business Intelligence in RetailDokument21 SeitenBusiness Intelligence in RetailGaurav Kumar100% (1)

- Most Common Punctuation Errors Made English and Tefl Majors Najah National University - 0 PDFDokument24 SeitenMost Common Punctuation Errors Made English and Tefl Majors Najah National University - 0 PDFDiawara MohamedNoch keine Bewertungen