Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

PSM

Hochgeladen von

vijaydh0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

25 Ansichten9 SeitenStrategy Mgt

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenStrategy Mgt

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

25 Ansichten9 SeitenPSM

Hochgeladen von

vijaydhStrategy Mgt

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 9

Technology Readiness for Innovative High-Tech Products: How

Consumers Perceive and Adopt New Technologies

Dr. Ahmet Emre Demirci, Anadolu University, Turkey

Dr. Nezihe Figen Ersoy, Anadolu University, Turkey

ABSTRACT

The products and services companies offer sometimes become commodities long before they are diffused and

adopted at desired levels by their target audiences. Shortening life cycles of products and services as well as

rapidly shrinking technology s-curves are forcing businesses to better structure their innovation efforts. While

these trends are vital to business sustainability and survival, understanding potential customers technology

readiness and their perceptions concerning certain products and services could provide businesses with a

leading-edge position in their domain. This study is a replication and an extension of Parasuramans study on the

Technology Readiness Index (TRI). Our research aims to uncover the possible differences between the number

and the structure of factors with regard to the technology readiness of potential customers.

INTRODUCTION

As the intensity of competition is rapidly increasing, more companies are offering technology-based products

and services to satisfy and exceed the ever-changing expectations of the customers. While the number of

innovative high-tech products and services is increasing as we speak, consumers experiences with these

products and services are becoming a focal point for companies striving to survive in todays digital world. Thus,

the question of why do certain individuals adopt new technologies, whereas others dont? is highly important

for companies offering technology-based products and services (Tsikriktsis, 2004). The answer to this question

has a direct relevance to the diffusion and adoption of innovative products. Because innovations that are

perceived by receivers as having greater relative advantage, trialability, compatibility, observability and less

complexity will be adopted more rapidly compared to other innovations without these qualities (Rogers, 1983).

Among many research streams that have dealt with this question, scholars and companies have increasingly been

giving the notion of technology readiness more attention recently. Before we extend our discussion, a framework

of what technology is ought to be given. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (2000)

defines technology as:

1. Systematic treatment of an art or craft:

a. The application of science, especially to industrial or commercial objectives.

b. The scientific method and material used to achieve a commercial or industrial objective.

2. Electronic or digital products and systems considered as a group: a store specializing in office technology.

According to Bush (McOmber, 1999) Technology is a form of human cultural activity that applies the

principles of science and mechanics to the solution of problems. It includes the resources, tools, processes,

personnel, and systems developed to perform tasks and create immediate particular, and personal and/or

competitive advantages in a given ecological, economic, and social context.

From the perspective stressing the commercial value of technology, high technology products and services can

be considered as the output of a planned industrial approach, research and development, and ongoing innovation

efforts. While these innovative products and services are offered to targeted consumer groups, the relationship

between technology, innovation and consumers adoption processes should be underlined.

Diffusion of Innovations

Diffusion is a process whereby an innovation spreads across a population of potential adopters over time through

various channels (Fichman and Kemerer, 1999). Thus, diffusion of innovation refers to how, why, and at what

rate new ideas and technology spread through different cultures. Individuals within the cultures are not passive

recipients of innovations. Although it varies in terms of the extent, they seek innovations, experiment with them,

evaluate them, develop feelings about them, complain about them, and gain experience with them often through

dialogue with other users (Greenhalgh et al., 2004). Experiences of customers and the perceived value of

innovations are among the main factors causing some innovations to spread more quickly than others. Also the

characteristics of an innovation have a major impact on its rate of adoption among members of a social system

(Rogers, 2002). In addition to the above-mentioned factors, technology readiness of potential users is among the

factors affecting how fast and to what extent potential users adopt a technology.

Technology Readiness (TR) and Customer Readiness (CR)

Explaining and predicting user adoption of new technology has a long history of attention in both academia and

practice. TR construct can be viewed as an overall state of mind resulting from a gestalt of mental enablers and

inhibitors that collectively determine a persons predisposition toward using new technologies (Lin, Shih, Sher,

2007).

Parasuraman (2000) has tried to define what affects a customers choice to turn to SSTs (Self-Service

Technologies) and other technology-based services depending on marketing view. He found there are some

characteristics that comply with the acceptance of new technologies or services resulting in interaction through

technology. Thus, the term technology-readiness refers to people's propensity to embrace and use new

technologies for accomplishing goals in home life and at work (Parasuraman, 2000). Lin and Hsieh (2007) found

that it is critical for firms currently using, or considering using SSTs to address the TR of customers. Lin and

Hsiehs results show that the higher the technology readiness of customers, the higher the satisfaction and

behavioral intentions generated when using self-service technologies.

At the measurement level, the Technology Readiness Index (TRI) was developed to measure peoples general

beliefs and some thinking on technology. TR construct comprises four sub-dimensions: optimism,

innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity. According to Tsikritis, explanations of these dimensions are

(Tsikritis, 2004):

Optimism: A positive view of technology and a belief that it offers people increased control, flexibility,

and efficiency in their lives.

You like the idea of doing business via computers because you are not limited to regular

business hours.

Technology gives people more control over their daily lives.

Technology makes you more efficient in your occupation.(Tsikritis, 2004)

Innovativeness: A tendency to be a technology pioneer and thought leader. Innovativeness measures

the extent to which an individual believes he or she is at the forefront of trying out new technology-

based products and/or services and is considered by others as an opinion leader on technology-related

issues.

You can usually figure out new high-tech products and services without the help of others.

In general, you are among the first in your circle of friends to acquire new technology when it

appears.

Discomfort: A perceived lack of control over technology and a feeling of being overwhelmed

by it. This represents the extent to which people have a general paranoia about technology-based

products and services, believing that they tend to be exclusionary rather than inclusive for all kinds of

people. The following statements illustrate the types of beliefs contributing to discomfort:

Sometimes you think that technology systems are not designed for use by ordinary people.

When you get technical support from a provider of a hi-tech product or service, you sometimes

feel as if you are being taken advantage of by someone who knows more than you do.

Insecurity: Distrust of technology and skepticism about its ability to work properly. Although somewhat

related to discomfort, this dimension focuses on specific aspects of technology-based transactions,

rather than on a lack of comfort with technology in general. The following statements illustrate the

types of beliefs contributing to insecurity:

You do not consider doing business with a place that can only be reached online.

If you provide information to a machine or over the Internet, you can never be sure if it really

gets to the right place.

Massey, Khatri, and Montoya-Weiss (2007) stress that TR encompasses more than the degree to which an

individual is relatively earlier in adopting an innovation. Parasuraman (2000) further explains it is possible for

the customer to have both positive and negative feelings about technology, especially high technology products

and services. His study also found that even technological optimists and innovators experience anxiety in the

same way as less technology-enthusiastic customers. As noted earlier, technology readiness (TR) refers to the

propensity of consumers to embrace and use new technologies for accomplishing goals. He also said that the

technology readiness construct refers to peoples propensity to embrace and use new technologies for

accomplishing goals in home life and work. The key contribution of this index, which seeks to identify a

consumers propensity to adopt and use new technologies, is in the finding that a consumers level of readiness

to adopt is positively affected by both the consumers level of optimism regarding the products ability to

provide substantial benefits and his/her level of innovativeness with reference to the tendency to pioneer new

ideas (Parasuraman, 2000).

In describing TR, Parasuraman and Colby (2001) identify five distinct groups: Explorers, Pioneers, Skeptics,

Paranoids, and Laggards. Explorers score higher on the contributors (optimism, innovativeness) and lower on

inhibitors (discomfort, insecurity) than the other segments. Explorers are a relatively easy group to attract when

a new technology-based product or service is introduced and represent the first wave of customers. Laggards are

the opposite of Explorers, ranking lower on the contributor factors and higher on the inhibitor factors than all the

groups as a whole. Laggards are also typically the last group to adopt a new technology-based product or service.

The middle three segments (Pioneers, Skeptics, and Paranoids) have more complicated beliefs about technology.

Pioneers share the optimism and innovative beliefs of Explorers, but they simultaneously feel some discomfort

and insecurity. They desire the benefits of technology, but are more practical about the difficulties and

challenges. Skeptics tend to be dispassionate about technology, but also have few inhibitions; thus, they need to

be convinced of the benefits. Paranoids may find technology interesting, but they are also concerned about risks,

and exhibit high degrees of discomfort and insecurity (Massey, Khatri and Montoya-Weiss, 2007). According to

Parasumans results, Table 1 shows the characteristics of technology segments (Jaafar et al., 2007).

Table 1. The Characteristics of Technology Segments

Technology segments Optimism Innovativeness Discomfort Insecurity

Explorers High High Low Low

Pioneers High High High High

Skeptics Low Low Low Low

Paranoids High Low High High

Laggards Low Low High High

Source: http://www.arl.org/libqual/events/oct2000msq/slides/parasuraman

Although new technology is proliferating in modern times, people may not easily accept it. Technology cannot

be accepted if consumers are not ready. As we said before, much previous research has discussed the relationship

between CR and SST (Liljander et al., 2006; Lin and Hsieh, 2006; Meuter et al., 2005; Parasuraman, 2000;

Tsikritis, 2004). The concept of Customer Readiness (CR) (Ho and Ko, 2008) is a state of mind a persons

predisposition toward using new technologies (Liljander et al., 2006). Meuter et al. (2005) referred to CR as a

condition or state in which a consumer is prepared and likely to try new technology services; it can be

conceptualized as role clarity, motivation, and ability. According to Parasuraman (2000), technology readiness

defined as being peoples propensity to embrace and use new technologies for accomplishing tasks in home life

and at work is composed of optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity

Ho and Kos study (2008) uses role clarity, motivation, ability, and optimism to measure the effects of CR on the

acceptance of Internet banking (Meuter et al., 2005; Parasuraman, 2000). Role clarity occurs when a customer

understands and has knowledge of what to do. Motivation both intrinsic and extrinsic is the customers desire

to receive the rewards. Ability is the required processing skills and confidence to complete the task. Finally,

optimism claims that people have a positive view of technology and believe that SST offers them flexibility,

efficiency, freedom, and benefits in their lives (Ho and Ko, 2008). Companies should understand all the motives

and perceptions that may have an effect on customers technology readiness as these factors could be an integral

part of new product development strategies.

Method

Research and questionnaire design

Survey form

The Technology Readiness Index (TRI) was used in the study. TRI is a multiple-item scale developed to

measure consumers readiness to embrace new technologies (Parasumaran, 2000). TRI consists of 36 statements

that put forward the drivers and inhibitors of technology readiness. The statements were evaluated by survey

participants according to a five-point Likert scale (-2 strongly disagree and 2 strongly agree).

Sample

Academic staff of Anadolu University forms the universe for this study. The survey instrument was distributed

through a Web-based surveying application. The Web link to the survey, along with the explanations, was

distributed to all academic staff. All the statements in the survey instrument were mandatory. The statements

appeared on the Web site one by one. As the survey instrument was designed originally in English, a pilot study

was carried out with 30 people to test the clarity of the statements translated into Turkish. The final shape was

given after the necessary corrections were made.

Answering all the questions in the survey took the participants 7-8 minutes. The Web link for the survey was

sent to 1,500 academic staff. Seventy one forms were not taken into consideration as the answers were not

complete or statistically unusable. Three hundred and twenty four survey forms were returned as suitable for

statistical analysis. The rate of return in this study is 22%.

Findings and results

Characteristics of the sample

Of the 324 survey participants, 51.2% were female and 48.8% were male. 23.1% were under 29 years old, 23.8%

were 30-34, 21.9% were 35-39, 13.6% were 40-44 and finally 17.6% were over 45 years old. In terms of

monthly income, 21.3% of the participants earned less than 1000 TRL, while 42.9% were earning 1500-2000

TRL, 18.2% were earning 2000-2500 TRL, and 17.6% were earning 2500 TRL and above. The majority of the

participants were held a doctoral degree (56.2%), while 15.1% held a bachelors degree and 28.4% held a

masters degree.

Table 2. Characteristics of the Sample

Frequency Percentage

Gender

Female 166 51.2

Male 158 48.8

Age

29 and less 75 23.1

30-34 77 23.8

35-39 71 21.9

40-44 44 13.6

45 and above 57 17.6

Income

(Average monthly)

1001 TRL and less 69 21.3

1501-2000 TRL 139 42.9

2001-2500 TRL 59 18.2

2501 TRL and above 57 17.6

Education

Bachelors 49 15.1

Masters 92 28.4

Doctorate 182 56.2

Factors in technological readiness

There are 36 items in total which may drive or inhibit technology readiness in the TRI measurement scale of

Parasuraman. To classify and sort out the variables, two-level principal component factor analysis was used in

this study. Eleven items with factor loadings of less than 0.40 were excluded from the original scale after the first

pass, and the final analysis was performed on 25 items. In concordance with Kaisers (1974) criteria, only the

factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained; and only the items with factor loadings and communalities

greater than 0.40 were included in the final factor structure. Cronbachs alpha values for each dimension were

computed to confirm the factors internal consistency.

It is necessary to test the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (Zhang et al. 2003) in

order to apply factor analysis on the statements included in TRI. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) was 0.850,

indicating that the sample was adequate for factor analysis (Kaiser, 1974).

According to principal component analysis, five factors had an eigenvalue equal to or greater than 1, explaining

a total of 58.11% of the variance. These factors are called Innovativeness, Insecurity, Optimism,

Discomfort and Interaction. In factor analysis, the percentage of the variance explained by each factor

indicates the relative significance of the factors.

Accordingly, the first factor, labelled as innovativeness, explained the largest part (24,55%) of the total variance,

having a greater significance than the other four factors. The innovativeness factor consists of seven statements

related to the innovation readiness of the people. The second factor, labelled as optimism, explained 14,50% of

the variance. This factor consists of eight statements related to technological optimism. The third factor, labelled

as insecurity, explained 8,45% of the variance. This factor consists of four statements related to the feeling of

insecurity. The fourth factor, labelled as discomfort, explained 5,90% of total variance. This factor consists of

four statements related to technological discomfort. And, finally, the fifth factor, labelled as interaction,

explained 4,72% of the variance. This factor consists of two statements related to the users perceived

importance of human interaction in technology-related services. All factor loadings are greater than 0.40 and the

cronbach alphas are greater than 0.69, while the total scale reliability is 0.85. All factors have a relatively high

coefficient score (see Table 3).

Table 2. Factors and Items on Technologic Readiness

Factors Factor Loadings Mean S.D.

Eigenvalues

(% of

variance)

Alpha

Factor 1: Innovativeness (7 items)

OPTIMISM6 .59 4.15 0.88

6.136

(24,55%)

.89

INNOVATIVENESS11 .77 3.45 1.14

INNOVATIVENESS13 .82 3.19 1.07

INNOVATIVENESS14 .79 3.76 1.06

INNOVATIVENESS15 .69 4.17 0.82

INNOVATIVENESS16 .82 3.65 1.10

INNOVATIVENESS17 .79 3.60 1.04

Factor 2: Optimism (8 items)

OPTIMISM1 .68 4.61 0.60

3.626

(14.50%)

.80

OPTIMISM2 .60 4.18 0.96

OPTIMISM3 .58 4.00 0.85

OPTIMISM5 .50 3.93 0.92

OPTIMISM7 .66 4.62 0.68

OPTIMISM8 .51 4.28 0.86

OPTIMISM9 .68 4.04 0.93

OPTIMISM10 .62 4.41 0.77

Factor 3: Insecurity (4 items)

INSECURITY28 .88 3.20 1.34

2.112

(8.45%)

.82

INSECURITY29 .87 3.09 1.30

INSECURITY31 .69 3.37 1.20

INSECURITY32 .60 3.45 1.31

Factor 4: Discomfort (4 items)

DISCOMFORT19 .59 3.43 1.06

1.476

(5.90%)

.69

DISCOMFORT25 .66 3.41 1.14

DISCOMFORT26 .78 3.89 0.97

DISCOMFORT27 .71 4.16 0.87

Factor 5: Interaction (2 items)

INSECURITY34 .82 3.91 1.04 1.179

(4.72%)

.78

INSECURITY35 .78 4.25 0.94

ANOVA and t-tests were applied to assess the demographic differentiations of the factors of technological

readiness (Table 4). With regards to the gender variable, innovativeness was found to be significantly different

compared to the other variables. According to the t-test results for the innovativeness factor, male respondent

values were assessed as higher than those of female respondents. According to Shashaani (1997), males are more

interested in computers and related technologies than are females and have more self-confidence in working with

computers. Also Venkatesh et al.s (2000) investigation of the determinants of technology adoption and usage

behavior confirmed that attitude toward using technology was more salient to men. With regards to age,

insecurity and discomfort were found to be significantly different compared to the other variables. Morris et al.

(2000) suggests that there are clear differences with age in the importance of various factors in technology

adoption and usage. According to their study, older workers feel less comfortable with using a new technology

compared to younger workers. Also Schumacher et al.s (2001) research reveals that elder users are less

comfortable and/or competent with computers and related technologies. None of the factors of technological

readiness were statistically different according to educational level and average income.

Table 4. Aspect Differentiation According to Demographics

Factors Gender Age Education Income

t P F P F P F P

Innovativeness -3.986 .000** 2.602 .036 1.555 .200 0.274 .844

Optimism -0.034 .973 1.843 .120 2.558 .055 0.285 .836

Insecurity 2.115 .035 5.441 .000** 0.604 .613 1.366 .253

Discomfort 0.075 .941 4.485 .002** 0.386 .763 1.091 .353

Interaction 0.209 .835 1.738 .141 0.571 .634 0.010 .999

* p <0.05 ; ** p <0.01

Conclusion

As mentioned at the beginning of the article, this study was performed to replicate the technology readiness

taxonomy Parasuraman and Colby developed. The idea behind this replication study was to test the technology

readiness index within Turkish culture. Although the results have provided strong support for their taxonomy, we

found another dimension that differs from the original configuration. We found that two statements included in

the original index was separately grouped by the Turkish respondents. Both statements were about the

customers preferences in the way the company interacts with them. Although these two statements were

grouped under the Insecurity dimension in Parasumarans study, Turkish respondents positioned the statements

as a seperate group. As both statements deal with company-customer interaction, we labelled the new factor

found in our study as Interaction.

We found this result meaningful as we considered the cultural differences. According to Hofstede (1983),

individualism and collectivism is one of the dimensions he put forward to explain national cultural differences.

Although both individualist and collectivist societies are integrated wholes, individualist society is loosely

integrated while collectivist society is tightly integrated. In other words, the ties between individuals are tighter

in collectivist cultures compared to individualist cultures. In contrast with the U.S., Turkey has a low

individualism score. Tan et al. (1998) found that people in collectivist cultures may be less willing to use

computer-mediated communication tools compared to people in individualist cultures. Another point is that

individualist societies are generally low-context cultures, where people have a lesser need for nonverbal cues,

and people communicate in an open and direct way. Conversely, collectivist societies are generally high-context

cultures where people communicate in a less open and direct way. Thus, gestures, allusions, and nonverbal cues

are sometimes important for the mutual communication of messages. Ross (2001) suggests that low-context

cultures may experience greater comfort with the use of electronic communications media because fewer

nonverbal cues are required than those from higher context cultures. On the other hand, high-context cultures

require many non-verbal cues for communication which could hardly be satisfied through electronic

communication.

In concordance with studies on cultural differences and communication, Turkish respondents, who, as a group,

belong to a collectivist and high-context culture, perceived the above mentioned questions in a different way and

separated them from their original group while stressing the relative importance of human touch in company-

customer interaction in a society having tight relationships between individuals. Our study reveals that cultural

factors can also have an effect on the technology readiness of people, therefore the rate of diffusion and adoption

of new technologies vary from culture to culture. While 70% of our respondents stated that human touch is very

important when doing business with a company, 80.5% of our respondents clearly stated that they prefer to

interact with a person instead of a computer. Thus, we believe that adding a new dimension stressing the cultural

differences affecting technology readiness would be beneficial to better explain the rate of diffusion and

adoption of new technologies.

Limitations and Future Research

The most important limitation in our study is that the study was done on a group with a strong educational

background. Above-avarage income level and high educational background may affect the level our group

exposes to new technologies. Thus, our respondents may have a higher technology readiness profile compared to

other parts of society. Further research on a more diversified sample could generate a more detailed insight into

the technology readiness of Turkish customers.

Although we excluded some questions, original scale was used in the study. However, the results of our study

revealed that the cultural differences may affect the technology readiness of people in a society. In further

studies which might be performed in various societies with major differences from U.S. culture, an extended

scale could be developed to cover some more statements to better measure the effect of cultural factors in

technology readiness.

Finally, characteristics of technology segments could be analysed for different cultures to identify if there are

any shifts between the groups derived from the cultural differences. Especially, a research on a society with

collectivist qualities could have a potential to reveal the shifts between the segments.

REFERENCES

Fichman, Robert G. and Kemerer, Chris F. (1999). The Illusory Diffusion of Innovation: An Examination of Assimilation

Gaps. Information Systems Research, Vol.10(3): 255-275

Greenhalgh, Trisha, Robert, Glenn, MacFarlane, Fraser, Bate, Paul and Kyriakidou, Olivia (2004). Diffusion of Innovations

in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, Vol.82(4): 581-629

Hofstede, Geert (1983). The Cultural Relativity of Organizational Practices and Theories. J ournal of International Business

Studies, Vol.14(2): 75-89

J aafar, Mastura, Abdul Aziz, Abdul Rashid, Ramayah, T., and Saad, Basri (2007) , Integrating Information Technology in

the Construction Industry: Technology Readiness Assessment of Malaysian Contractors. International J ournal of Project

Management, Vol. 25(2): 115120

Liljander, V., Gillberg, F., Gummerus, J . and Riel, A.V. (2006). Technology Readiness and the Evaluation and Adoption of

Self-Service Technologies. J ournal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol.13(3): 177-191

Lin, C.H. and Peng, C.H. (2005). The Cultural Dimension of Technology Readiness on Customer Value Chain in

Technology-Based Service Encounters. The J ournal of American Academy of Business, Vol.7(1):176-180

Lin, Chien-Hsin, Shih, Hsin-Yu, and Sher Peter J . (2007). Integrating Technology Readiness into Technology

Acceptance:The TRAM Model. Psychology & Marketing, Vol.24(7): 641-657

Lin, J .C. and Hsieh, P.L. (2006). The Role of Technology Readiness in Customers Perception and Adoption of Self-Service

Technologies. International J ournal of Service Industry Management, Vol.17(5): 497-517

Lin, J iun-Sheng Chris and Hsieh, Pei-Ling (2007). The Influence of Technology Readiness on Satisfaction and Behavioral

Intentions Toward Self-Service Technologies. Computers in Human Behavior, Vol.23(3):1597-1615

Lu, J ., Yu, C.S., Liu, C. and Yao, J .E. (2003). Technology Acceptance Model For Wireless Internet. Internet Research:

Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, Vol.13(3):206-222

Massey, Anne P., Khatri, Vijay, and Montoya-Weiss, Mitzi M. (2007). Usability of Online Services: The Role of

Technology Readiness and Context. Decision Sciences, Vol.38(2): 277

McOmber, J ames (1999). Technological Autonomy and Three Definitions of Technology. Journal of Communication,

Vol.49(3): 137-153

Meuter, M.L., Bitner, M.J ., Ostrom, A.L. and Brown, S.W. (2005). Choosing Among Alternative Service Delivery Modes:

An Investigation of Customer Trial of Self-Service Technologies. J ournal of Marketing, Vol.69(2): 61-83

Meuter, M.L., Ostrom, A.L., Bitner, M.J . and Roundtree, R. (2003). The Influence of Technology Anxiety on Consumer Use

and Experiences with Self-Service Technologies. J ournal of Business Research, Vol.56(11): 899-906

Morris, Michael G, and Venkatesh, Viswanath (2000). Age Differences in Technology Adoption Decisions: Implications for

a Changing Workplace. Personnel Psychology, Vol.53(2): 375-403

Parasuraman, A. (2000). Technology-Readiness Index (TRI): A Multiple-Item Scale to Measure Readiness to Embrace New

Technologies. J ournal of Service Research, Vol.2(4): 307-320

Parasuraman, A., & Colby, C. L. (2001). Techno-ready marketing: How and why customers adopt technology. New York:

The Free Press, 224

Rogers, Everett M. (1983), Diffusion of Innovations, Third Edition, The Free Press, London

Rogers, Everett M. (2002). Diffusion of Preventive Innovations. Addictive Behaviors, Vol.27(6): 989-993

Ross, Douglas N. (2001). Electronic Communications: Do Cultural Dimensions Matter?. American Business Review,

Vol.19(2): 75-81

Schumacher, P. and Morahan-Martin, J . (2001). Gender, Internet and Computer Attitudes and Experiences. Computers in

Human Behavior, Vol.17(1): 95-110

Shashaani, Lily (1997). Gender Differences in Computer Attitudes and Use Among College Students. J ournal of Educational

Computing Research, Vol.16(1): 37-51

Shu-Hsun Ho and Ying-Yin Ko, (2008). Effects of Self-Service Technology on Customer Value and Customer Readiness:

The Case of Internet Banking, Internet Research, Vol.18(4): 427-446

Tan, Bernard C.Y., Wei, Kwok-Kee, Watson, Richard T., Clapper, Danial L. and Mclean, Ephraim R. (1998). Computer-

Mediated Communication and Majority Influence: Assessing the Impact in an Individualistic and a Collectivistic Culture,

Management Science, Vol.44(9): 1263-1278

Tsikriktsis, Nikos (2004). A Technology ReadinessBased Taxonomy of Customers: A Replication and Extension. J ournal of

Service Research, Vol.7(1): 42-52

Venkatesh, Viswanath, Morris, Michael G., and Ackerman, Philip L. (2000). A Longitudinal Field Investigation of Gender

Differences in Individual Technology Adoption Decision-Making Processes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, Vol.83(1): 33-60

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Pdi 1Dokument2 SeitenPdi 1vijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction to Research MethodologyDokument10 SeitenIntroduction to Research MethodologyvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sampling 876432Dokument29 SeitenSampling 876432vijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of DesignDokument19 SeitenPrinciples of Designapi-518483960Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion B: Principles of Design and Body TypesDokument11 SeitenFashion B: Principles of Design and Body TypesvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Readiness Assessment InstructionsDokument9 SeitenReadiness Assessment InstructionsvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Change-Readiness Assessment: Understanding the Seven TraitsDokument6 SeitenChange-Readiness Assessment: Understanding the Seven TraitsvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design Elements & Principles in ClothingDokument13 SeitenDesign Elements & Principles in Clothingvijaydh100% (1)

- Grid Method: Art Technique in Accuracy Scale Up and Scale DownDokument13 SeitenGrid Method: Art Technique in Accuracy Scale Up and Scale DownvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colors in FashionDokument59 SeitenColors in FashionvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- FMM - Computer Applications in Financial Market Marking SchemeDokument7 SeitenFMM - Computer Applications in Financial Market Marking SchemeRijo ThomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foreshortening - What It Means and How To Paint ItDokument44 SeitenForeshortening - What It Means and How To Paint ItvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indigo: (,, ,, Blue, And)Dokument23 SeitenIndigo: (,, ,, Blue, And)vijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Market LevelsDokument14 SeitenMarket LevelsvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Products and Planning Fashion Market ResearchDokument25 SeitenFashion Products and Planning Fashion Market ResearchvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

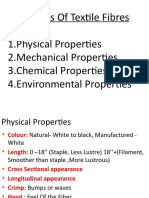

- Properties of Textile Fibres 1.physical Properties 2.mechanical Properties 3.chemical Properties 4.environmental PropertiesDokument4 SeitenProperties of Textile Fibres 1.physical Properties 2.mechanical Properties 3.chemical Properties 4.environmental PropertiesvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multi Screening The Who What When MarketersDokument16 SeitenMulti Screening The Who What When MarketersvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Donner NotesDokument4 SeitenDonner NotesvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Needs and Market OrientationDokument5 SeitenCustomer Needs and Market OrientationvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer ValueDokument6 SeitenCustomer ValuevijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Branch & BoundDokument8 SeitenBranch & BoundvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section 3 - Chap 3 - Structure of Interest RatesDokument13 SeitenSection 3 - Chap 3 - Structure of Interest RatesvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- FINAL Ecosystem Toolkit Draft - Print VersionDokument32 SeitenFINAL Ecosystem Toolkit Draft - Print VersionvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Telecom TrainingDokument4 SeitenTelecom TrainingvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treasury BillsDokument3 SeitenTreasury BillsvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- S7.2 - TRI by ParasuramanDokument36 SeitenS7.2 - TRI by ParasuramanvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modelling With Linear ProgDokument22 SeitenModelling With Linear ProgvijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2Dokument38 SeitenChapter 2vijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heineken Success Story 112309Dokument7 SeitenHeineken Success Story 112309vijaydhNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Module 1 - The Entrepreneurial MindDokument10 SeitenModule 1 - The Entrepreneurial Mindmilo santosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health and Safety Management SystemsDokument16 SeitenHealth and Safety Management SystemsclementNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motivation PresentationDokument65 SeitenMotivation PresentationK S Manikantan Nair67% (3)

- Kyriakos Voulinos A1 Professional LearningDokument6 SeitenKyriakos Voulinos A1 Professional Learningapi-664780361Noch keine Bewertungen

- 178-182 Proficiency Expert Teacher's Resource Material - Exam Practice 2 PDFDokument5 Seiten178-182 Proficiency Expert Teacher's Resource Material - Exam Practice 2 PDFHai Anh50% (2)

- PT 2Dokument13 SeitenPT 2Norma PanaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay With DialogueDokument3 SeitenEssay With Dialogued3gpmvqw100% (2)

- Positive Perspectives Matter Enhancing Positive Organizational BehaviorDokument15 SeitenPositive Perspectives Matter Enhancing Positive Organizational BehaviorGlobal Research and Development ServicesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Studies On Organizational Behavior Relevant IssuesDokument28 SeitenCase Studies On Organizational Behavior Relevant IssuesHasib HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- BRM MSDDokument27 SeitenBRM MSDSunil JoshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- SBI Clerk Prelims Memory Based-ENGLISH-1-2024Dokument4 SeitenSBI Clerk Prelims Memory Based-ENGLISH-1-2024sailuteluguNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1Dokument23 SeitenChapter 1Jeysel CarpioNoch keine Bewertungen

- THESIS Final 2 PDFDokument176 SeitenTHESIS Final 2 PDFReece GailNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDFDokument577 SeitenPDFOmaff HurtadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ed 203 Module 1Dokument26 SeitenEd 203 Module 1Aberia Juwimae Kristel AberiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Escape Room Unconference in Toronto Discusses Industry TrendsDokument1 SeiteEscape Room Unconference in Toronto Discusses Industry TrendsManuel Ricardo CristanchoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Innovation PDFDokument22 SeitenManagement Innovation PDFRomer GesmundoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maslow's Hierarchy Needs Self-ActualizationDokument3 SeitenMaslow's Hierarchy Needs Self-Actualizationdexter esperanzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solution Manual For Management 12th Edition by DaftDokument20 SeitenSolution Manual For Management 12th Edition by DaftSaxon D Pinlac67% (3)

- Digital Play and Media TransferenceDokument9 SeitenDigital Play and Media TransferenceLaura OioliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Worksheets #3 Batch 1: Observations of Teaching-Learning in Actual School Environment (Field Study 1)Dokument5 SeitenWorksheets #3 Batch 1: Observations of Teaching-Learning in Actual School Environment (Field Study 1)Pre Loved OlshoppeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic LeadershipDokument3 SeitenStrategic LeadershipAHmad RanjhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting Class Participation, Palawan National SchoolDokument40 SeitenFactors Affecting Class Participation, Palawan National SchoolRachel Anna Esman Lorenzo67% (3)

- Chap 20 LeadershipDokument4 SeitenChap 20 LeadershipklossmaddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of Performance Appraisal On Employee Productivity in Organizations: A Case Study of Selected Who Offices in East AfricaDokument13 SeitenThe Influence of Performance Appraisal On Employee Productivity in Organizations: A Case Study of Selected Who Offices in East AfricaJoel FdezNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIPD Employee Engagement and MotivationDokument2 SeitenCIPD Employee Engagement and MotivationAhanaf RashidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Musculoskeletal BiomechanicsDokument254 SeitenHuman Musculoskeletal Biomechanicsuilifteng100% (2)

- Important Questions Mba-Ii Sem Organisational BehaviourDokument24 SeitenImportant Questions Mba-Ii Sem Organisational Behaviourvikas__ccNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals of Human Resource Management: Decenzo and RobbinsDokument30 SeitenFundamentals of Human Resource Management: Decenzo and RobbinsAbdul AhadNoch keine Bewertungen