Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Brother Is A Nutritionist. My Sisters Are Mathematicians

Hochgeladen von

yanieggOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Brother Is A Nutritionist. My Sisters Are Mathematicians

Hochgeladen von

yanieggCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

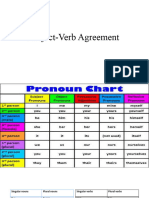

Basic Principle: Singular subjects need singular verbs; plural subjects need plural verbs.

My

brother is a nutritionist. My sisters are mathematicians.

See the section on Plurals for additional help with subject-verb agreement.

The indefnite pronouns anyone, everyone, someone, no one, nobody are always singular

and, therefore, require singular verbs.

veryone has done his or her homewor!.

Somebody has left her purse.

Some indefnite pronouns " such as all, some " are singular or plural depending on what

they#re referring to. $%s the thing referred to countable or not&' (e careful choosing a verb

to accompany such pronouns.

Some of the beads are missing.

Some of the water is gone.

)n the other hand, there is one indefnite pronoun, none, that can be either singular or

plural* it often doesn#t matter whether you use a singular or a plural verb " unless

something else in the sentence determines its number. $+riters generally thin! of none as

meaning not any and will choose a plural verb, as in ,-one of the engines are wor!ing,,

but when something else ma!es us regard none as meaning not one, we want a singular

verb, as in ,-one of the food is fresh.,'

-one of you claims responsibility for this incident&

-one of you claim responsibility for this incident&

-one of the students have done their homewor!. $%n this last e.ample, the word

their precludes the use of the singular verb.

Some indefnite pronouns are particularly troublesome Everyone and everybody $listed

above, also' certainly feel li!e more than one person and, therefore, students are

sometimes tempted to use a plural verb with them. They are always singular, though.

Each is often followed by a prepositional phrase ending in a plural word $ach of the cars',

thus confusing the verb choice. Each, too, is always singular and requires a singular verb.

veryone has fnished his or her homewor!.

/ou would always say, ,verybody is here., This means that the word is singular and

nothing will change that.

ach of the students is responsible for doing his or her wor! in the library.

0on#t let the word ,students, confuse you* the subject is each and each is always singular

" ach is responsible.

1hrases such as together with, as well as, and along with are not the same as

and. The phrase introduced by as well as or along with will modify the earlier

word $mayor in this case', but it does not compound the subjects $as the word

and would do'.

The mayor as well as his brothers is going to prison.

The mayor and his brothers are going to jail.

The pronouns neither and either are singular and require singular verbs even

though they seem to be referring, in a sense, to two things.

-either of the two tra2c lights is wor!ing.

+hich shirt do you want for 3hristmas&

ither is fne with me.

%n informal writing, neither and either sometimes ta!e a plural verb when these pronouns

are followed by a prepositional phrase beginning with of. This is particularly true of

interrogative constructions4 ,5ave either of you two clowns read the assignment&, ,6re

either of you ta!ing this seriously&, (urchfeld calls this ,a clash between notional and

actual agreement.,7

The conjunction or does not conjoin $as and does'4 when nor or or is used the

subject closer to the verb determines the number of the verb. +hether the

subject comes before or after the verb doesn#t matter* the pro.imity

determines the number.

ither my father or my brothers are going to sell the house.

-either my brothers nor my father is going to sell the house.

Are either my brothers or my father responsible&

Is either my father or my brothers responsible&

(ecause a sentence li!e ,-either my brothers nor my father is going to sell the house,

sounds peculiar, it is probably a good idea to put the plural subject closer to the verb

whenever that is possible.

The words there and here are never subjects.

There are two reasons 8plural subject9 for this.

There is no reason for this.

5ere are two apples.

+ith these constructions $called e.pletive constructions', the subject follows the verb but

still determines the number of the verb.

:erbs in the present tense for third-person, singular subjects $he, she, it and

anything those words can stand for' have s-endings. )ther verbs do not add s-

endings.

5e loves and she loves and they love; and . . . .

5e loves and she loves and they love; and . . . .

Sometimes modifers will get betwen a subject and its verb, but these modifers must not

confuse the agreement between the subject and its verb.

The mayor, who has been convicted along with his four brothers on four counts of various

crimes but who also seems, li!e a cat, to have several political lives, is fnally going to jail.

Sometimes nouns ta!e weird forms and can fool us into thin!ing they#re plural when

they#re really singular and vice-versa. 3onsult the section on the Plural Forms of

Nouns and the section on Collective Nouns for additional help. +ords such as

glasses, pants, pliers, and scissors are regarded as plural $and require plural verbs'

unless they#re preceded the phrase pair of $in which case the word pair becomes the

subject'.

My glasses were on the bed.

My pants were torn.

6 pair of plaid trousers is in the closet.

Some words end in s and appear to be plural but are really singular and require

singular verbs.

The news from the front is bad.

Measles is a dangerous disease for pregnant women.

)n the other hand, some words ending in s refer to a single thing but are nonetheless plural and

require a plural verb.

My assets were wiped out in the depression.

The average wor!er#s earnings have gone up dramatically.

)ur than!s go to the wor!ers who supported the union.

The names of sports teams that do not end in ,s, will ta!e a plural verb4 the Miami 5eat have been

loo!ing < , The 3onnecticut Sun are hoping that new talent < . See the section on plurals for help

with this problem.

=ractional e.pressions such as half of, a part of, a percentage of, a majority of are

sometimes singular and sometimes plural, depending on the meaning. $The same is

true, of course, when all, any, more, most and some act as subjects.' Sums and

products of mathematical processes are e.pressed as singular and require singular

verbs. The e.pression ,more than one, $oddly enough' ta!es a singular verb4 ,More

than one student has tried this.,

Some of the voters are still angry.

6 large percentage of the older population is voting against her.

Two-ffths of the troops were lost in the battle.

Two-ffths of the vineyard was destroyed by fre.

=orty percent of the students are in favor of changing the policy.

=orty percent of the student body is in favor of changing the policy.

Two and two is four.

=our times four divided by two is eight.

%f your sentence compounds a positive and a negative subject and one is plural, the

other singular, the verb should agree with the positive subject.

The department members but not the chair have decided not to teach on

:alentine#s 0ay.

%t is not the faculty members but the president who decides this issue.

%t was the spea!er, not his ideas, that has provoked the students to riot.

Denition

6dverbs are words that modify

a verb $5e drove slowly. " 5ow did he drive&'

an adjective $5e drove a very fast car. " 5ow fast was his car&'

another adverb $She moved quite slowly down the aisle. " 5ow slowly did she move&'

6s we will see, adverbs often tell when, where, why, or under what conditions something happens

or happened. 6dverbs frequently end in ly* however, many words and phrases not ending in ly

serve an adverbial function and an ly ending is not a guarantee that a word is an adverb. The

words lovely, lonely, motherly, friendly, neighborly, for instance, are adjectives4

That lovely woman lives in a friendly neighborhood.

%f a group of words containing a subject and verb acts as an adverb $modifying the verb of a

sentence', it is called an Adverb Clause!

+hen this class is over, we#re going to the movies.

+hen a group of words not containing a subject and verb acts as an adverb, it is called an

adverbial phrase. Prepositional phrases frequently have adverbial functions $telling place and

time, modifying the verb'4

5e went to the movies.

She wor!s on holidays.

They lived in 3anada during the war.

6nd Innitive phrases can act as adverbs $usually telling why'4

She hurried to the mainland to see her brother.

The senator ran to catch the bus.

(ut there are other !inds of adverbial phrases4

5e calls his mother as often as possible.

6dverbs can modify ad"ectives, but an adjective cannot modify an adverb.

Thus we would say that ,the students showed a really wonderful attitude, and

that ,the students showed a wonderfully casual attitude, and that ,my

professor is really tall, but not ,5e ran real fast.,

>i!e adjectives, adverbs can have comparative and superlative forms to show

degree.

+al! faster if you want to !eep up with me.

The student who reads fastest will fnish frst.

+e often use more and most, less and least to show degree with adverbs4

+ith snea!ers on, she could move more quic!ly among the patients.

The ?owers were the most beautifully arranged creations %#ve ever seen.

She wor!ed less confdently after her accident.

That was the least s!illfully done performance %#ve seen in years.

The as " as construction can be used to create adverbs that e.press sameness or equality4 ,5e

can#t run as fast as his sister.,

6 handful of adverbs have two forms, one that ends in ly and one that doesn#t. %n certain cases,

the two forms have di@erent meanings4

5e arrived late.

>ately, he couldn#t seem to be on time for anything.

%n most cases, however, the form without the ly ending should be reserved for casual situations4

She certainly drives slow in that old (uic! of hers.

5e did wrong by her.

5e spo!e sharp, quic!, and to the point.

6dverbs often function as intensiers, conveying a greater or lesser emphasis to something.

%ntensifers are said to have three di@erent functions4 they can emphasiAe, amplify, or downtone.

5ere are some e.amples4

mphasiAers4

o % really don#t believe him.

o 5e literally wrec!ed his mother#s car.

o She simply ignored me.

o They#re going to be late, for sure.

6mplifers4

o The teacher completely rejected her proposal.

o % absolutely refuse to attend any more faculty meetings.

o They heartily endorsed the new restaurant.

o % so wanted to go with them.

o +e !now this city well.

0owntoners4

o % !ind of li!e this college.

o Boe sort of felt betrayed by his sister.

o 5is mother mildly disapproved his actions.

o +e can improve on this to some e.tent.

o The boss almost quit after that.

o The school was all but ruined by the storm.

6dverbs $as well as adjectives' in their various degrees can be accompanied by premodifers4

She runs very fast.

+e#re going to run out of material all the faster

This issue is addressed in the section on degrees in adjectives.

=or this section on intensifers, we are indebted to ! "rammar of #ontemporary English by

Candolph Duir!, Sidney Ereenbaum, Eeo@rey >eech, and Ban Svartvi!. >ongman Eroup4 >ondon.

FGHI. pages JKI to JLH. .amples our own.

#sing Adverbs in a Numbered $ist

+ithin the normal ?ow of te.t, it#s nearly always a bad idea to number items beyond three or four,

at the most. 6nything beyond that, you#re better o@ with a vertical list that uses numbers $F, M, K,

etc.'. 6lso, in such a list, don#t use adverbs $with an ly ending'* use instead the unin?ected ordinal

number $frst, second, third, fourth, ffth, etc.'. =irst $not frstly', it#s unclear what the adverb is

modifying. Second $not secondly', it#s unnecessary. Third $not thirdly', after you get beyond

,secondly,, it starts to sound silly. 6dverbs that number in this manner are treated as disjuncts

$see below.'

Adverbs %e Can Do %ithout

Ceview the section on &eing Concise for some advice on adverbs that we can eliminate to the

beneft of our prose4 intensiers such as very, e$tremely, and really that don#t intensify anything

and e'pletive constructions $,There are several boo!s that address this issue.,'

3lic! on ,>olly#s

1lace, to read and

hear (ob 0orough#s

,Eet /our 6dverbs

5ere, $from

Scholastic Coc!,

FGHJ'.

Schoolhouse Coc!N

and its characters

and other

elements are

trademar!s and

service mar!s of

6merican

(roadcasting

3ompanies, %nc.

Osed with

permission.

(inds of Adverbs

Adverbs of )anner

She moved slowly and spo!e quietly.

Adverbs of Place

She has lived on the island all her life.

She still lives there now.

Adverbs of Fre*uency

She ta!es the boat to the mainland every day.

She often goes by herself.

Adverbs of +ime

She tries to get bac! before dar!.

%t#s starting to get dar! now.

She fnished her tea frst.

She left early.

Adverbs of Purpose

She drives her boat slowly to avoid hitting the roc!s.

She shops in several stores to get the best buys.

Positions of Adverbs

)ne of the hallmar!s of adverbs is their ability to move around in a sentence. 6dverbs of manner

are particularly ?e.ible in this regard.

Solemnly the minister addressed her congregation.

The minister solemnly addressed her congregation.

The minister addressed her congregation solemnly.

The following adverbs of frequency appear in various points in these sentences4

(efore the main verb4 % never get up before nine o#cloc!.

(etween the au.iliary verb and the main verb4 % have rarely written to my brother without

a good reason.

(efore the verb used to: % always used to see him at his summer home.

%ndefnite adverbs of time can appear either before the verb or between the au.iliary and the main

verb4

5e fnally showed up for batting practice.

She has recently retired.

,rder of Adverbs

There is a basic order in which adverbs will appear when there is more than one. %t is similar to

+he -oyal ,rder of Ad"ectives, but it is even more ?e.ible.

+.E -,/A$ ,-DE- ,F AD0E-&1

0erb )anner Place Fre*uency +ime Purpose

(eth

swims

enthusiastically in the pool every morning before dawn to !eep in shape.

0ad

wal!s

impatiently into town every afternoon before supper to get a newspaper.

Tashond

a naps

in her room every morning before lunch.

%n actual practice, of course, it would be highly unusual to have a string of adverbial

modifers beyond two or three $at the most'. (ecause the placement of adverbs is so

?e.ible, one or two of the modifers would probably move to the beginning of the

sentence4 ,very afternoon before supper, 0ad impatiently wal!s into town to get a

newspaper., +hen that happens, the introductory adverbial modifers are usually set o@

with a comma.

)ore Notes on Adverb ,rder

6s a general principle, shorter adverbial phrases precede longer adverbial phrases, regardless of

content. %n the following sentence, an adverb of time precedes an adverb of frequency because it

is shorter $and simpler'4

0ad ta!es a bris! wal! before brea!fast every day of his life.

6 second principle4 among similar adverbial phrases of !ind $manner, place, frequency, etc.', the

more specifc adverbial phrase comes frst4

My grandmother was born in a sod house on the plains of northern -ebras!a.

She promised to meet him for lunch ne.t Tuesday.

(ringing an adverbial modifer to the beginning of the sentence can place special emphasis on that

modifer. This is particularly useful with adverbs of manner4

Slowly, ever so carefully, Besse flled the co@ee cup up to the brim, even above the brim.

)ccasionally, but only occasionally, one of these lemons will get by the inspectors.

Inappropriate Adverb ,rder

Ceview the section on )isplaced )odiers for some additional ideas on placement. Modifers

can sometimes attach themselves to and thus modify words that they ought not to modify.

They reported that Eiuseppe (alle, a uropean roc! star, had died on the si. o#cloc! news.

3learly, it would be better to move the underlined modifer to a position immediately after ,they

reported, or even to the beginning of the sentence " so the poor man doesn#t die on television.

Misplacement can also occur with very simple modifers, such as only and barely4

She only grew to be four feet tall.

%t would be better if ,She grew to be only four feet tall.,

Ad"uncts2 Dis"uncts2 and Con"uncts

Cegardless of its position, an adverb is often neatly integrated into the ?ow of a sentence. +hen

this is true, as it almost always is, the adverb is called an adjunct. $-otice the underlined adjuncts

or adjunctive adverbs in the frst two sentences of this paragraph.' +hen the adverb does not ft

into the ?ow of the clause, it is called a disjunct or a conjunct and is often set o@ by a comma or

set of commas. 6 disjunct frequently acts as a !ind of evaluation of the rest of the sentence.

6lthough it usually modifes the verb, we could say that it modifes the entire clause, too. -otice

how ,too, is a disjunct in the sentence immediately before this one* that same word can also serve

as an adjunct adverbial modifer4 %t#s too hot to play outside. 5ere are two more disjunctive

adverbs4

=ran!ly, Martha, % don#t give a hoot.

=ortunately, no one was hurt.

3onjuncts, on the other hand, serve a connector function within the ?ow of the te.t, signaling a

transition between ideas.

%f they start smo!ing those awful cigars, then %#m not staying.

+e#ve told the landlord about this ceiling again and again, and yet he#s done nothing to f.

it.

6t the e.treme edge of this category, we have the purely conjunctive device !nown as the

conjunctive adverb $often called the adverbial conjunction'4

Bose has spent years preparing for this event* nevertheless, he#s the most nervous person

here.

% love this school* however, % don#t thin! % can a@ord the tuition.

6uthority for this section4 ! %niversity "rammar of English by Candolph Duir! and Sidney

Ereenbaum. >ongman Eroup4 sse., ngland. FGGK. FMP. Osed with permission. .amples our own.

1ome 1pecial Cases

The adverbs enough and not enough usually ta!e a postmodifer position4

%s that music loud enough&

These shoes are not big enough.

%n a roomful of elderly people, you must remember to spea! loudly enough.

$-otice, though, that when enough functions as an adjective, it can come before the noun4

0id she give us enough time&

The adverb enough is often followed by an infnitive4

She didn#t run fast enough to win.

The adverb too comes before adjectives and other adverbs4

She ran too fast.

She wor!s too quic!ly.

%f too comes after the adverb it is probably a disjunct $meaning also' and is usually set o@ with a

comma4

/asmin wor!s hard. She wor!s quic!ly, too.

The adverb too is often followed by an infnitive4

She runs too slowly to enter this race.

6nother common construction with the adverb too is too followed by a prepositional phrase " for

Q the object of the preposition " followed by an infnitive4

This mil! is too hot for a baby to drin!.

-elative Adverbs

6djectival clauses are sometimes introduced by what are called the relative adverbs4 where,

when, and why. 6lthough the entire clause is adjectival and will modify a noun, the relative word

itself fulflls an adverbial function $modifying a verb within its own clause'.

The relative adverb where will begin a clause that modifes a noun of place4

My entire family now worships in the church where my great grandfather used to be minister.

The relative pronoun ,where, modifes the verb ,used to be, $which ma!es it adverbial', but the

entire clause $,where my great grandfather used to be minister,' modifes the word ,church.,

6 when clause will modify nouns of time4

My favorite month is always =ebruary, when we celebrate :alentine#s 0ay and 1residents# 0ay.

6nd a why clause will modify the noun reason:

0o you !now the reason why %sabel isn#t in class today&

+e sometimes leave out the relative adverb in such clauses, and many writers prefer ,that, to

,why, in a clause referring to ,reason,4

0o you !now the reason why %sabel isn#t in class today&

% always loo! forward to the day when we begin our summer vacation.

% !now the reason that men li!e motorcycles.

6uthority for this section4 %nderstanding English "rammar by Martha Rolln. Jrth dition. MacMillan

1ublishing 3ompany4 -ew /or!. FGGJ.

0iewpoint2 Focus2 and Negative Adverbs

6 viewpoint adverb generally comes after a noun and is related to an adjective that precedes

that noun4

6 successful athletic team is often a good team scholastically.

%nvesting all our money in snowmobiles was probably not a sound idea fnancially.

/ou will sometimes hear a phrase li!e ,scholastically spea!ing, or ,fnancially spea!ing, in these

circumstances, but the word ,spea!ing, is seldom necessary.

6 focus adverb indicates that what is being communicated is limited to the part that is focused* a

focus adverb will tend either to limit the sense of the sentence $,5e got an 6 just for attending the

class.,' or to act as an additive $,5e got an 6 in addition to being published.,

6lthough negative constructions li!e the words ,not, and ,never, are usually found embedded

within a verb string " ,5e has never been much help to his mother., " they are technically not

part of the verb* they are, indeed, adverbs. 5owever, a so-called negative adverb creates a

negative meaning in a sentence without the use of the usual noSnotSneitherSnorSnever

constructions4

5e seldom visits.

She hardly eats anything since the accident.

6fter her long and tedious lectures, rarely was anyone awa!e.

6 preposition describes a relationship between other words in a sentence. %n itself, a word li!e ,in,

or ,after, is rather meaningless and hard to defne in mere words. =or instance, when you do try to

defne a preposition li!e ,in, or ,between, or ,on,, you invariably use your hands to show how

something is situated in relationship to something else. 1repositions are nearly always combined

with other words in structures called prepositional phrases. 1repositional phrases can be made

up of a million di@erent words, but they tend to be built the same4 a preposition followed by a

determiner and an adjective or two, followed by a pronoun or noun $called the object of the

preposition'. This whole phrase, in turn, ta!es on a modifying role, acting as an ad"ective or an

adverb, locating something in time and space, modifying a noun, or telling when or where or

under what conditions something happened.

3onsider the professor#s des! and all the prepositional phrases we can use while tal!ing about it.

/ou can sit before the des! $or in front of the des!'. The professor can sit on the des! $when he#s

being informal' or behind the des!, and then his feet are under the des! or beneath the des!.

5e can stand beside the des! $meaning ne't to the des!', before the des!, between the des!

and you, or even on the des! $if he#s really strange'. %f he#s clumsy, he can bump into the des! or

try to wal! through the des! $and stu@ would fall o3 the des!'. 1assing his hands over the des!

or resting his elbows upon the des!, he often loo!s across the des! and spea!s of the des! or

concerning the des! as if there were nothing else like the des!. (ecause he thin!s of nothing

e'cept the des!, sometimes you wonder about the des!, what#s in the des!, what he paid for the

des!, and if he could live without the des!. /ou can wal! toward the des!, to the des!, around

the des!, by the des!, and even past the des! while he sits at the des! or leans against the

des!.

6ll of this happens, of course, in time4 during the class, before the class, until the class,

throughout the class, after the class, etc. 6nd the professor can sit there in a bad mood 8another

adverbial construction9.

Those words in bold blue font are all prepositions. Some prepositions do other things besides

locate in space or time " ,My brother is li&e my father., ,veryone in the class e$cept me got the

answer., " but nearly all of them modify in one way or another. %t is possible for a preposition

phrase to act as a noun " ,0uring a church service is not a good time to discuss picnic plans, or

,%n the South 1acifc is where % long to be, " but this is seldom appropriate in formal or academic

writing.

3lic! .E-E for a list of common prepositions that will be easy to print out.

/ou may have learned that ending a sentence with a

preposition is a serious breach of grammatical etiquette. %t

doesn#t ta!e a grammarian to spot a sentence-ending

preposition, so this is an easy rule to get caught up on $T'.

6lthough it is often easy to remedy the o@ending preposition,

sometimes it isn#t, and repair e@orts sometimes result in a

clumsy sentence. ,%ndicate the boo! you are quoting from, is

not greatly improved with ,%ndicate from which boo! you are

quoting.,

(ased on sha!y historical precedent, the rule itself is a

latecomer to the rules of writing. Those who disli!e the rule are

fond of recalling 3hurchill#s rejoinder4 ,That is nonsense up with

which % shall not put., +e should also remember the child#s

complaint4 ,+hat did you bring that boo! that % don#t li!e to be

read to out of up for&,

%s it any wonder that prepositions create such troubles for students for whom nglish is a second

language& +e say we are at the hospital to visit a friend who is in the hospital. +e lie in bed but on

the couch. +e watch a flm at the theater but on television. =or native spea!ers, these little words

present little di2culty, but try to learn another language, any other language, and you will quic!ly

discover that prepositions are troublesome wherever you live and learn. This page contains some

interesting $sometimes troublesome' prepositions with brief usage notes. To address all the

potential di2culties with prepositions in idiomatic usage would require volumes, and the only way

nglish language learners can begin to master the intricacies of preposition usage is through

practice and paying close attention to speech and the written word. Reeping a good dictionary

close at hand $to hand&' is an important frst step.

Prepositions of +ime! at, on2 and in

+e use at to designate specifc times.

The train is due at FM4FL p.m.

+e use on to designate days and dates.

My brother is coming on Monday.

+e#re having a party on the =ourth of Buly.

+e use in for nonspecifc times during a day, a month, a season, or a year.

She li!es to jog in the morning.

%t#s too cold in winter to run outside.

5e started the job in FGHF.

5e#s going to quit in 6ugust.

Prepositions of Place! at, on2 and in

+e use at for specifc addresses.

Erammar nglish lives at LL (oretA Coad in 0urham.

+e use on to designate names of streets, avenues, etc.

5er house is on (oretA Coad.

6nd we use in for the names of land-areas $towns, counties, states, countries, and continents'.

She lives in 0urham.

0urham is in +indham 3ounty.

+indham 3ounty is in 3onnecticut.

Prepositions of $ocation! in, at2 and on

and No Preposition

IN

$the' bed7

the bedroom

the car

$the' class7

the library7

school7

A+

class7

home

the library7

the o2ce

school7

wor!

,N

the bed7

the ceiling

the ?oor

the horse

the plane

the train

N,

P-EP,1I+I,N

downstairs

downtown

inside

outside

upstairs

uptown

7 /ou may sometimes use di@erent prepositions for these locations.

Prepositions of )ovement! to

and No Preposition

+e use to in order to e.press movement toward a place.

They were driving to wor! together.

She#s going to the dentist#s o2ce this morning.

'oward and towards are also helpful prepositions to e.press movement. These are simply variant

spellings of the same word* use whichever sounds better to you.

+e#re moving toward the light.

This is a big step towards the project#s completion.

+ith the words home, downtown, uptown, inside, outside, downstairs, upstairs, we use no

preposition.

Erandma went upstairs

Erandpa went home.

They both went outside.

Prepositions of +ime! for and since

+e use for when we measure time $seconds, minutes, hours, days, months, years'.

5e held his breath for seven minutes.

She#s lived there for seven years.

The (ritish and %rish have been quarreling for seven centuries.

+e use since with a specifc date or time.

5e#s wor!ed here since FGHU.

She#s been sitting in the waiting room since two-thirty.

Prepositions with Nouns2 Ad"ectives2 and 0erbs4

1repositions are sometimes so frmly wedded to other words that they have practically become

one word. $%n fact, in other languages, such as Eerman, they would have become one word.' This

occurs in three categories4 nouns, adjectives, and verbs.

N,#N1 and P-EP,1I+I,N1

approval of

awareness of

belief in

concern for

confusion

about

desire for

fondness

for

grasp of

hatred of

hope for

interest in

love of

need for

participation

in

reason for

respect for

success in

understandin

g of

AD5EC+I0E1 and P-EP,1I+I,N1

afraid of

angry at

aware of

capable of

careless about

familiar with

fond of

happy about

interested in

jealous of

made of

married to

proud of

similar to

sorry for

sure of

tired of

worried about

0E-&1 and P-EP,1I+I,N1

apologiAe for

as! about

as! for

belong to

bring up

give up

grow up

loo! for

loo! forward to

loo! up

prepare for

study for

tal! about

thin! about

trust in

care for

fnd out

ma!e up

pay for

wor! for

worry about

6 combination of verb and preposition is called a phrasal verb. The word that is joined to the verb

is then called a particle. 1lease refer to the brief section we have prepared on phrasal verbs for

an e.planation.

Idiomatic E'pressions with Prepositions

agree to a proposal, with a person, on a price, in principle

argue about a matter, with a person, for or against a proposition

compare to to show li!enesses, with to show di@erences $sometimes similarities'

correspond to a thing, with a person

di@er from an unli!e thing, with a person

live at an address, in a house or city, on a street, with other people

#nnecessary Prepositions

%n everyday speech, we fall into some bad habits, using prepositions where they are not necessary.

%t would be a good idea to eliminate these words altogether, but we must be especially careful not

to use them in formal, academic prose.

She met up with the new coach in the hallway.

The boo! fell o@ of the des!.

5e threw the boo! out of the window.

She wouldn#t let the cat inside of the house. 8or use ,in,9

+here did they go to&

1ut the lamp in bac! of the couch. 8use ,behind, instead9

+here is your college at&

Prepositions in Parallel Form

$3lic! .E-E for a defnition and discussion of parallelism.' +hen two words or phrases are used

in parallel and require the same preposition to be idiomatically correct, the preposition does not

have to be used twice.

/ou can wear that outft in summer and in winter.

The female was both attracted by and distracted by the male#s dance.

5owever, when the idiomatic use of phrases calls for di@erent prepositions, we must be careful not

to omit one of them.

The children were interested in and disgusted by the movie.

%t was clear that this player could both contribute to and learn from every game he played.

5e was fascinated by and enamored of this beguiling woman.

6rticles, determiners, and quantifers are those little words that precede and modify nouns4

the teacher, a college, a bit of honey, that person, those people, whatever purpose, either way,

your choice

Sometimes these words will tell the reader or listener whether we#re referring to a specifc or

general thing $the garage out bac!* ! horseT ! horseT My !ingdom for a horseT'* sometimes they

tell how much or how many $lots of trees, several boo!s, a great deal of confusion'. The choice of

the proper article or determiner to precede a noun or noun phrase is usually not a problem for

writers who have grown up spea!ing nglish, nor is it a serious problem for non-native writers

whose frst language is a romance language such as Spanish. =or other writers, though, this can be

a considerable obstacle on the way to their mastery of nglish. %n fact, some students from eastern

uropean countries " where their native language has either no articles or an altogether di@erent

system of choosing articles and determiners " fnd that these ,little words, can create problems

long after every other aspect of nglish has been mastered.

0eterminers are said to ,mar!, nouns. That is to say, you !now a determiner will be followed by a

noun. Some categories of determiners are limited $there are only three articles, a handful of

possessive pronouns, etc.', but the possessive nouns are as limitless as nouns themselves. This

limited nature of most determiner categories, however, e.plains why determiners are grouped

apart from adjectives even though both serve a modifying function. +e can imagine that the

language will never tire of inventing new adjectives* the determiners $e.cept for those possessive

nouns', on the other hand, are well established, and this class of words is not going to grow in

number. These categories of determiners are as follows4 the articles $an, a, the " see below*

possessive nouns $Boe#s, the priest#s, my mother#s'* possessive pronouns, $his, your, their, whose,

etc.'* numbers $one, two, etc.'* indefnite pronouns $few, more, each, every, either, all, both, some,

any, etc.'* and demonstrative pronouns. The demonstratives $this, that, these, those, such' are

discussed in the section on 0emonstrative 1ronouns. -otice that the possessive nouns di@er from

the other determiners in that they, themselves, are often accompanied by other determiners4 ,my

mother#s rug,, ,the priests#s collar,, ,a dog#s life.,

This categoriAation of determiners is based on %nderstanding English "rammar by Martha Rolln.

Jrth dition. MacMillan 1ublishing 3ompany4 -ew /or!. FGGJ.

1ome Notes on 6uantiers

>i!e articles, *uantiers are words that precede and modify nouns. They tell us how many or how

much. Selecting the correct quantifer depends on your understanding the distinction between

Count and Non7Count Nouns. =or our purposes, we will choose the count noun trees and the

non-count noun dancing4

'he following (uanti)ers will wor& with count nouns:

many trees

a few trees

few trees

several trees

a couple of trees

none of the trees

'he following (uanti)ers will wor& with noncount nouns:

not much dancing

a little dancing

little dancing

a bit of dancing

a good deal of dancing

a great deal of dancing

no dancing

'he following (uanti)ers will wor& with both count and noncount nouns:

all of the treesSdancing

some treesSdancing

most of the treesSdancing

enough treesSdancing

a lot of treesSdancing

lots of treesSdancing

plenty of treesSdancing

a lack of treesSdancing

%n formal academic writing, it is usually better to use many and much rather than phrases such as

a lot of, lots of and plenty of.

There is an important di@erence between 8a little8 and 8little8 $used with non-count words' and

between 8a few8 and 8few8 $used with count words'. %f % say that Tashonda has a little e.perience

in management that means that although Tashonda is no great e.pert she does have some

e.perience and that e.perience might well be enough for our purposes. %f % say that Tashonda has

little e.perience in management that means that she doesn#t have enough e.perience. %f % say that

3harlie owns a few boo!s on >atin 6merican literature that means that he has some some boo!s "

not a lot of boo!s, but probably enough for our purposes. %f % say that 3harlie owns few boo!s on

>atin 6merican literature, that means he doesn#t have enough for our purposes and we#d better go

to the library.

Onless it is combined with of, the quantifer 8much8 is reserved for questions and negative

statements4

Much of the snow has already melted.

5ow much snow fell yesterday&

-ot much.

-ote that the quantifer 8most of the8 must include the defnite article the when it modifes a

specifc noun, whether it#s a count or a non-count noun4 ,most of the instructors at this college

have a doctorate,* ,most of the water has evaporated., +ith a general plural noun, however $when

you are not referring to a specifc entity', the ,of the, is dropped4

Most colleges have their own admissions policy.

Most students apply to several colleges.

6uthority for this last paragraph4 'he Scott, *oresman +andboo& for ,riters by Ma.ine 5airston

and Bohn B. CusA!iewicA. Jth ed. 5arper3ollins4 -ew /or!. FGGP. .amples our own.

6n indefnite article is sometimes used in conjunction with the quantifer many, thus joining a

plural quantifer with a singular noun $which then ta!es a singular verb'4

Many a young man has fallen in love with her golden hair.

Many an apple has fallen by )ctober.

This construction lends itself to a somewhat literary e@ect $some would say a stu@y or archaic

e@ect' and is best used sparingly, if at all.

+he Need to Combine 1entences

Sentences have to be combined to avoid the monotony that would surely result if all sentences

were brief and of equal length. $%f you haven#t already read them, see the sections on Avoiding

Primer 1tyle and 1entence 0ariety.' 1art of the writer#s tas! is to employ whatever music is

available to him or her in language, and part of language#s music lies within the rhythms of varied

sentence length and structure. ven poets who write within the formal limits and sameness of an

iambic pentameter beat will sometimes stri!e a chord against that beat and vary the structure of

their clauses and sentence length, thus !eeping the te.t alive and the reader awa!e. This section

will e.plore some of the techniques we ordinary writers use to combine sentences.

Compounding 1entences

6 compound sentence consists of two or more independent clauses. That means that there

are at least two units of thought within the sentence, either one of which can stand by itself as its

own sentence. The clauses of a compound sentence are either separated by a semicolon

$relatively rare' or connected by a coordinating con"unction $which is, more often than not,

preceded by a comma'. 6nd the two most common coordinating conjunctions are and and but.

$The others are or, for, yet, and so.' This is the simplest technique we have for combining ideas4

Meriwether >ewis is justly famous for his e.pedition into the territory of the >ouisiana

1urchase and beyond2 but few people !now of his contributions to natural science.

>ewis had been well trained by scientists in 1hiladelphia prior to his e.pedition2 and he

was a curious man by nature.

-otice that the and does little more than lin! one idea to another* the but also lin!s, but it does

more wor! in terms of establishing an interesting relationship between ideas. The and is part of the

immediate language arsenal of children and of dreams4 one thing simply comes after another and

the logical relationship between the ideas is not always evident or important. The word but $and

the other coordinators' is at a slightly higher level of argument.

3lic! here to review the rules of comma usage when you combine two independent clauses with a

coordinating conjunction.

Compounding 1entence Elements

+ithin a sentence, ideas can be connected by compounding various sentence elements4 subjects,

verbs, objects or whole predicates, modifers, etc. -otice that when two such elements of a

sentence are compounded with a coordinating conjunction $as opposed to the two independent

clauses of a compound sentence', the conjunction is usually adequate and no comma is required.

1ub"ects! +hen two or more subjects are doing parallel things, they can often be combined as a

compounded subject.

+or!ing together, President 5e3erson and )eriwether $ewis convinced 3ongress to

raise money for the e.pedition.

,b"ects! +hen the subject$s' isSare acting upon two or more things in parallel, the objects can be

combined.

1resident Be@erson believed that the headwaters of the Missouri reached all the way to

the 3anadian border.

5e also believed that meant he could claim all that land for the Onited States.

1resident Be@erson believed that the headwaters of the Missouri might reach all the way to

the 3anadian border and that he could claim all that land for the Onited States.

-otice that the objects must be parallel in construction4 Be@erson believed that this was true and

that was true. %f the objects are not parallel $Be@erson was convinced of two things4 that the

Missouri reached all the way to the 3anadian border and wanted to begin the e.pedition during his

term in o2ce.' the sentence can go awry. 3lic! here to review the principles of parallelism.

0erbs and verbals! +hen the subject$s' isSare doing two things at once, ideas can sometimes be

combined by compounding verbs and verb forms.

5e studied the biological and natural sciences.

5e learned how to categoriAe and draw animals accurately.

5e studied the biological and natural sciences and learned how to categoriAe and draw

animals accurately.

-otice that there is no comma preceding the ,and learned, connecting the compounded elements

above.

%n 1hiladelphia, >ewis learned to chart the movement of the stars.

5e also learned to analyAe their movements with mathematical precision.

%n 1hiladelphia, >ewis learned to chart and analy9e the movement of the stars with

mathematical precision.

-. / %n 1hiladelphia, >ewis learned to chart the stars and analy9e their movements with

mathematical precision.

$-otice in this second version that we don#t have to repeat the ,to, of the infnitive to maintain

parallel form.'

)odiers! +henever it is appropriate, modifers such as prepositional phrases can be

compounded.

>ewis and 3lar! recruited some of their adventurers from river-town bars.

They also used recruits from various military outposts.

>ewis and 3lar! recruited their adventurers from river7town bars and various military

outposts4

-otice that we do not need to repeat the preposition from to ma!e the ideas successfully parallel

in form.

1ubordinating ,ne Clause to Another

The act of coordinating clauses simply lin!s ideas* subordinating one clause to another establishes

a more comple. relationship between ideas, showing that one idea depends on another in some

way4 a chronological development, a cause-and-e@ect relationship, a conditional relationship, etc.

+illiam 3lar! was not o2cially granted the ran! of captain prior to the e.pedition#s

departure.

3aptain >ewis more or less ignored this technicality and treated 3lar! as his equal in

authority and ran!.

Although +illiam 3lar! was not o2cially granted the ran! of captain prior to the

e.pedition#s departure2 Captain >ewis more or less ignored this technicality and treated

3lar! as his equal in authority and ran!.

The e.plorers approached the headwaters of the Missouri.

They discovered, to their horror, that the Coc!y Mountain range stood between them and

their goal, a passage to the 1acifc.

As the e.plorers approached the headwaters of the Missouri2 they discovered, to their

horror, that the Coc!y Mountain range stood between them and their goal, a passage to

the 1acifc.

+hen we use subordination of clauses to combine ideas, the rules of punctuation are very

important. %t might be a good idea to review the denition of clauses at this point and the uses

of the comma in setting o@ introductory and parenthetical elements.

#sing Appositives to Connect Ideas

The appositive is probably the most e2cient technique we have for combining ideas. 6n

appositive or appositive phrase is a renaming, a re-identifcation, of something earlier in the

te.t. /ou can thin! of an appositive as a modifying clause from which the clausal machinery

$usually a relative pronoun and a lin!ing verb' has been removed. 6n appositive is often, but not

always, a parenthetical element which requires a pair of commas to set it o@ from the rest of the

sentence.

Sacagawea, who was one of the %ndian wives of 3harbonneau, who was a =rench fur-

trader, accompanied the e.pedition as a translator.

6 pregnant, ffteen-year-old %ndian woman2 1acagawea2 one of the wives of the =rench

fur-trader Charbonneau, accompanied the e.pedition as a translator.

-otice that in the second sentence, above, Sacagawea#s name is a parenthetical element

$structurally, the sentence adequately identifes her as ,a pregnant, ffteen-year-old %ndian

woman,', and thus her name is set o@ by commas* 3harbonneau#s name, however, is essential to

the meaning of the sentence $otherwise, which fur-trader are we tal!ing about&' and is not set o@

by a pair of commas. 3lic! here for additional help identifying and punctuating around

parenthetical elements.

#sing Participial Phrases to Connect Ideas

6 writer can integrate the idea of one sentence into a larger structure by turning that idea into a

modifying phrase.

3aptain >ewis allowed his men to ma!e important decisions in a democratic manner.

This democratic attitude fostered a spirit of togetherness and commitment on the part of

>ewis#s fellow e.plorers.

Allowing his men to make important decisions in a democratic manner2 >ewis

fostered a spirit of togetherness and commitment among his fellow e.plorers.

%n the sentence above, the participial phrase modifes the subject of the sentence, 0ewis.

1hrases li!e this are usually set o@ from the rest of the sentence with a comma.

The e.peditionary force was completely out of touch with their families for over two

years.

They put their faith entirely in >ewis and 3lar!#s leadership.

They never once rebelled against their authority.

Completely out of touch with their families for over two years2 the men of the

e.pedition put their faith in >ewis and 3lar!#s leadership and never once rebelled against

their authority.

#sing Absolute Phrases to Connect Ideas

1erhaps the most elegant " and most misunderstood " method of combining ideas is the

absolute phrase. This phrase, which is often found at the beginning of sentence, is made up of a

noun $the phrase#s ,subject,' followed, more often than not, by a participle. )ther modifers might

also be part of the phrase. There is no true verb in an absolute phrase, however, and it is always

treated as a parenthetical element, an introductory modifer, which is set o@ by a comma.

The absolute phrase might be confused with a participial phrase, and the di@erence between them

is structurally slight but signifcant. The participial phrase does not contain the subject-participle

relationship of the absolute phrase* it modifes the subject of the the independent clause that

follows. The absolute phrase, on the other hand, is said to modify the entire clause that follows. %n

the frst combined sentence below, for instance, the absolute phrase modifes the subject 0ewis,

but it also modifes the verb, telling us ,under what conditions, or ,in what way, or ,how, he

disappointed the world. The absolute phrase thus modifes the entire subsequent clause and

should not be confused with a dangling participle, which must modify the subject which

immediately follows.

>ewis#s fame and fortune was virtually guaranteed by his e.ploits.

>ewis disappointed the entire world by ine.plicably failing to publish his journals.

.is fame and fortune virtually guaranteed by his e'ploits2 >ewis disappointed the

entire world by ine.plicably failing to publish his journals.

>ewis#s long journey was fnally completed.

5is men in the 3orps of 0iscovery were dispersed.

>ewis died a few years later on his way bac! to +ashington, 0.3., completely alone.

.is long "ourney completed and his men in the Corps of Discovery dispersed2

>ewis died a few years later on his way bac! to +ashington, 0.3., completely alone.

The most convincing ideas in the world, e.pressed in the most beautiful sentences, will

move no one unless those ideas are properly connected. Onless readers can move easily

from one thought to another, they will surely fnd something else to read or turn on the

television.

1roviding transitions between ideas is largely a matter of attitude. /ou must never assume

that your readers !now what you !now. %n fact, it#s a good idea to assume not only that

your readers need all the information that you have and need to !now how you arrived at

the point you#re at, but also that they are not quite as quic! as you are. /ou might be able

to leap from one side of the stream to the other* believe that your readers need some

stepping stones and be sure to place them in readily accessible and visible spots.

There are four basic mechanical considerations in providing transitions between ideas4

using transitional e.pressions, repeating !ey words and phrases, using pronoun reference,

and using parallel form.

#1IN: +-AN1I+I,NA$ +A:1

Transitional tags run the gamut from the most simple " the little conjunctions4 and, but,

nor, for, yet, or, $and sometimes' so " to more comple. signals that ideas are somehow

connected " the conjunctive adverbs and transitional e.pressions such as however,

moreover, nevertheless, on the other hand.

=or additional information on conjunctions, clic! .E-E.

The use of the little conjunctions " especially and and but " comes naturally for most

writers. 5owever, the question whether one can begin a sentence with a small conjunction

often arises. %sn#t the conjunction at the beginning of the sentence a sign that the sentence

should have been connected to the prior sentence& +ell, sometimes, yes. (ut often the

initial conjunction calls attention to the sentence in an e@ective way, and that#s just what

you want. )ver-used, beginning a sentence with a conjunction can be distracting, but the

device can add a refreshing dash to a sentence and speed the narrative ?ow of your te.t.

Cestrictions against beginning a sentence with and or but are based on sha!y grammatical

foundations* some of the most in?uential writers in the language have been happily

ignoring such restrictions for centuries.7

5ere is a chart of the transitional devices $also called con"unctive adverbs or adverbial

con"unctions' accompanied with a simplifed defnition of function $note that some

devices appear with more than one defnition'4

addition

again, also, and, and then, besides, equally important,

fnally, frst, further, furthermore, in addition, in the frst

place, last, moreover, ne.t, second, still, too

comparison also, in the same way, li!ewise, similarly

concession granted, naturally, of course

contrast

although, and yet, at the same time, but at the same

time, despite that, even so, even though, for all that,

however, in contrast, in spite of, instead, nevertheless,

notwithstanding, on the contrary, on the other hand,

otherwise, regardless, still, though, yet

emphasis certainly, indeed, in fact, of course

e'ample or

illustration

after all, as an illustration, even, for e.ample, for instance,

in conclusion, indeed, in fact, in other words, in short, it is

true, of course, namely, specifcally, that is, to illustrate,

thus, truly

summary

all in all, altogether, as has been said, fnally, in brief, in

conclusion, in other words, in particular, in short, in

simpler terms, in summary, on the whole, that is,

therefore, to put it di@erently, to summariAe

time se*uence

after a while, afterward, again, also, and then, as long as,

at last, at length, at that time, before, besides, earlier,

eventually, fnally, formerly, further, furthermore, in

addition, in the frst place, in the past, last, lately,

meanwhile, moreover, ne.t, now, presently, second,

shortly, simultaneously, since, so far, soon, still,

subsequently, then, thereafter, too, until, until now, when

6 word of caution4 0o not interlard your te.t with transitional e.pressions merely because

you !now these devices connect ideas. They must appear, naturally, where they belong, or

they#ll stic! li!e a fshbone in your reader#s craw. $=or that same reason, there is no point in

trying to memori1e this vast list.' )n the other hand, if you can read your entire essay and

discover none of these transitional devices, then you must wonder what, if anything, is

holding your ideas together. 1ractice by inserting a tentative however, nevertheless,

conse(uently. Ceread the essay later to see if these words provide the glue you needed at

those points.

-epetition of (ey %ords and Phrases

The ability to connect ideas by means of repetition of !ey words and phrases sometimes

meets a natural resistance based on the fear of being repetitive. +e#ve been trained to

loathe redundancy. -ow we must learn that catching a word or phrase that#s important to a

reader#s comprehension of a piece and replaying that word or phrase creates a musical

motif in that reader#s head. Onless it is overwor!ed and obtrusive, repetition lends itself to

a sense of coherence $or at least to the illusion of coherence'. Cemember >incoln#s advice4

/ou can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the

time, but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time.

%n fact, you can#t forget >incoln#s advice, because it has become part of the music of our

language.

Cemember to use this device to lin! paragraphs as well as sentences.

Pronoun -eference

1ronouns quite naturally connect ideas because pronouns almost always refer the reader

to something earlier in the te.t. % cannot say ,This is true because . . ., without causing the

reader to consider what ,this, could mean. Thus, the pronoun causes the reader to sum up,

quic!ly and subconsciously, what was said before $what this is' before going on to the

because part of my reasoning.

+e should hardly need to add, however, that it must always be perfectly clear what a

pronoun refers to. %f my reader cannot instantly !now what this is, then my sentence is

ambiguous and misleading. 6lso, do not rely on unclear pronoun references to avoid

responsibility4 ,They say that . . .,

Parallelism

Music in prose is often the result of parallelism, the deliberate repetition of larger

structures of phrases, even clauses and whole sentences. +e urge you to read the Euide#s

section on Parallelism and ta!e the accompanying quiA on recogniAing parallel form $and

repairing sentences that ought to use parallel form but don#t'. 1ay special attention to the

guided tour through the parallel intricacies within 6braham >incoln#s Eettysburg 6ddress.

Coherence Devices in Action

%n our section on writing the Argumentative Essay, we have a complete student essay

$,3ry, +olf, " at the bottom of that document' which we have analyAed in terms of

argumentative development and in which we have paid special attention to the

connective devices holding ideas together.

>oo! at the following paragraph4

The ancient gyptians were masters of preserving dead people#s bodies by ma!ing

mummies of them. Mummies several thousand years old have been discovered

nearly intact. The s!in, hair, teeth, fngernails and toenails, and facial features of

the mummies were evident. %t is possible to diagnose the disease they su@ered in

life, such as smallpo., arthritis, and nutritional defciencies. The process was

remar!ably e@ective. Sometimes apparent were the fatal aVictions of the dead

people4 a middle-aged !ing died from a blow on the head, and polio !illed a child

!ing. Mummifcation consisted of removing the internal organs, applying natural

preservatives inside and out, and then wrapping the body in layers of bandages.

Though wea!, this paragraph is not a total washout. %t starts with a topic sentence, and the

sentences that follow are clearly related to the topic sentence. %n the language of writing,

the paragraph is uni)ed $i.e., it contains no irrelevant details'. 5owever, the paragraph is

not coherent. The sentences are disconnected from each other, ma!ing it di2cult for the

reader to follow the writer#s train of thought.

(elow is the same paragraph revised for coherence. 2talics indicates pronouns and

repeatedSrestated !ey words, bold indicates transitional tag-words, and underlining

indicates parallel structures.

The ancient gyptians were masters of preserving dead people#s bodies by ma&ing

mummies of them. In short, mummi)cation consisted of removing the internal

organs, applying natural preservatives inside and out, and then wrapping the body

in layers of bandages. And the process was remar!ably e@ective. Indeed,

mummies several thousand years old have been discovered nearly intact. 'heir

s!in, hair, teeth, fngernails and toenails, and facial features are still evident. 'heir

diseases in life, such as smallpo., arthritis, and nutritional defciencies, are still

diagnosable. Even their fatal aVictions are still apparent4 a middle-aged !ing died

from a blow on the head* a child !ing died from polio.

The paragraph is now much more coherent. The organiAation of the information and the

lin!s between sentences help readers move easily from one sentence to the ne.t. -otice

how this writer uses a variety of coherence devices, sometimes in combination, to achieve

overall paragraph coherence.

76uthority4 'he 3ew *owler4s 5odern English %sage edited by C.+. (urchfeld. 3larendon

1ress4 ).ford, ngland. FGGP. Osed with the permission of ).ford Oniversity 1ress.

6 typical e.pository paragraph starts with a controlling idea or claim, which it then

e.plains, develops, or supports with evidence. 1aragraph sprawl occurs when digressions

are introduced into an otherwise focused and unifed discussion. 0igressions and

deviations often come in the form of irrelevant details or shifts in focus.

Irrelevant Details

+hen % was growing up, one of the places % enjoyed most was the cherry tree in the

bac! yard. (ehind the yard was an alley and then more houses. very summer

when the cherries began to ripen, % used to spend hours high in the tree, pic!ing

and eating the sweet, sun-warmed cherries. My mother always worried about my

falling out of the tree, but % never did. (ut % had some competition for the cherries

" ?oc!s of birds that enjoyed them as much as % did and would perch all over the

tree, devouring the fruit whenever % wasn#t there. % used to wonder why the grown-

ups never ate any of the cherries* but actually when the birds and % had fnished,

there weren#t many left.

-o sentence is completely irrelevant to the general topic of this paragraph $the cherry

tree', but the sentences Behind the yard was an alley and then more houses and 5y

mother always worried about my falling out of the tree, but 2 never did do not develop the

specifc idea in the frst sentence4 enjoyment of the cherry tree.

1hift in Focus

F

%t is a fact that capital

punishment is not a deterrent to

crime.

M

Statistics show that in

states with capital punishment,

murder rates are the same or

almost the same as in states

without capital punishment.

K

%t is

also true that it is more

e.pensive to put a person on

death row than in life

imprisonment because of the

costs of ma.imum security.

J

Onfortunately, capital

punishment has been used

unjustly.

L

Statistics show that

every e.ecution is of a man and

that nine out of ten are blac!.

P

So

prejudice shows right through.

)nce again, no sentence in this paragraph $to the

left' is completely irrelevant to the general topic

$capital punishment', but the specifc focus of this

paragraph shifts abruptly twice. The paragraph

starts out with a clear claim in sentence ;4 2t is a

fact that capital punishment is not a deterrent to

crime. Sentence < provides evidence in support of

the initial claim4 Statistics show that in states with

capital punishment, murder rates are the same or

almost the same as in states without capital

punishment. Sentence =, however, shifts the focus

from capital punishment as a deterrent to crime to

the cost of incarceration4 2t is also true that it is

more e$pensive to put a person on death row than

in life imprisonment because of the costs of

ma$imum security. Sentence > once again shifts

the focus, this time to issues of justice4

%nfortunately, capital punishment has been used

unjustly. Sentences ? and @, Statistics show that

every e$ecution is of a man and that nine out of

ten are blac& and So prejudice shows right

through, follow from J if one believes that

e.ecuting men and blac!s is in fact evidence of

injustice and prejudice. More importantly,

however, we are now a long way o@ from the

original claim, that capital punishment does not

deter crime. The focus has shifted from deterrence

to e.pense to fairness.

The following paragraph on the same topic is much more e@ectively focused and unifed4

F

The punishment of criminals has

always been a problem for

society.

M

3itiAens have had to

decide whether o@enders such as

frst-degree murderers should be

!illed in a gas chamber,

imprisoned for life, or

rehabilitated and given a second

chance in society.

K

Many citiAens

argue that serious criminals

should be e.ecuted.

J

They

believe that !illing criminals will

set an e.ample for others and

also rid society of a cumbersome

burden.

L

)ther citiAens say that

no one has the right to ta!e a life

Sentence ; puts forth the main claim4 'he

punishment of criminals has always been a

problem for society. Sentence < specifes the e.act

nature of the problem by listing society#s choices4

#iti1ens have had to decide whether o6enders

such as )rstdegree murderers should be &illed in

a gas chamber, imprisoned for life, or rehabilitated

and given a second chance in society. Sentence =

further develops the topic by stating one point of

view4 5any citi1ens argue that serious criminals

should be e$ecuted. The reasons for this point of

view are then provided in sentence >4 'hey

believe that &illing criminals will set an e$ample

for others and also rid society of a cumbersome

burden. Sentence ? states an opposing point of

view4 -ther citi1ens say that no one has the right

and that capital punishment is

not a deterrent to crime.

P

They

believe that society as well as the

criminal is responsible for the

crimes and that !illing the

criminal does not solve the

problems of either society or the

criminal.

to ta&e a life and that capital punishment is not a

deterrent to crime. Sentence @ states the reason

for the opposing point of view4 'hey believe that

society as well as the criminal is responsible for

the crimes and that &illing the criminal does not

solve the problems of either society or the

criminal.

+opic 1entences

6ll three paragraphs start out well with a topic sentence. 6 topic sentence is a sentence

whose main idea or claim controls the rest of the paragraph* the body of a paragraph

e.plains, develops or supports with evidence the topic sentence#s main idea or claim. The

topic sentence is usually the frst sentence of a paragraph, but not necessarily. %t may

come, for e.ample, after a transition sentence* it may even come at the end of a

paragraph.

Topic sentences are not the only way to organiAe a paragraph, and not all paragraphs need

a topic sentence. =or e.ample, paragraphs that describe, narrate, or detail the steps in an

e.periment do not usually need topic sentences. Topic sentences are useful, however, in

paragraphs that analyAe and argue. Topic sentences are particularly useful for writers who

have di2culty developing focused, unifed paragraphs $i.e., writers who tend to sprawl'.

Topic sentences help these writers develop a main idea or claim for their paragraphs, and,

perhaps most importantly, they help these writers stay focused and !eep paragraphs

manageable.

Topic sentences are also useful to readers because they guide them through sometimes

comple. arguments. Many well-!nown, e.perienced writers e@ectively use topic sentences

to bridge between paragraphs. 5ere#s an e.ample of how one professional writer does this4

Soon after the spraying had ended there were unmista!able signs that all was not well.

+ithin two days dead and dying fsh, including many young salmon, were found along the

ban!s of the stream. (roo! trout also appeared among the dead fsh, and along the roads

and in the woods birds were dying. 6ll the life of the stream was stilled. (efore the

spraying there had been a rich assortment of the water life that forms the food of salmon

and trout " caddis ?y larvae, living in loosely ftting protective cases of leaves, stems or

gravel cemented together with saliva, stone?y nymphs clinging to roc!s in the swirling

currents, and the wormli!e larvae of blac!?ies edging the stones under riVes or where the

stream spills over steeply slanting roc!s. (ut now the stream insects were dead, !illed by

00T, and there was nothing for a young salmon to eat.

Cachel 3arson, Silent Spring

The frst part of 3arson#s topic sentence " Soon after the spraying had ended " is a

transitional clause that loo!s bac! to the previous topic4 00T spraying. Topic sentences

often begin with such transitional clauses referring to the previous paragraph. The second

part of the topic sentence " there were unmista&able signs that all was not well " shapes

and controls what follows. This !ind of bridging helps the reader follow 3arson#s argument.

-otice, too, how 3arson further helps the reader follow her argument by providing a more

focused version of the topic sentence later in the paragraph " !ll the life of the stream

was stilled. This sentence tells us e.actly what 3arson meant by all was not well.

Denition of a 1entence

(efore elaborating too much on the nature of sentences or trying to defne a sentence#s parts, it

might be wise to defne a sentence itself. A sentence is a group of words containing a

sub"ect and predicate. Sometimes, the subject is ,understood,, as in a command4 ,8/ou9 go ne.t

door and get a cup of sugar., That probably means that the shortest possible complete sentence is

something li!e ,EoT, 6 sentence ought to e.press a thought that can stand by itself, but it would

be helpful to review the section on 1entence Fragments for additional information on thoughts

that cannot stand by themselves and sentences !nown as ,stylistic fragments., The various +ypes

of 1entences, structurally, are defned, with e.amples, under the section on sentence variety.

Sentences are also defned according to function4 declarative $most of the sentences we use',

interrogative $which as! a question " ,+hat#s your name&,', e.clamatory $,There#s a fre in the

!itchenT,', and imperative $,0on#t drin! thatT,'

%n Sha!espeare#s +enry 27, Part 8 $%%iv', we see that great ,stu@ed cloa!-bag of guts,, =alsta@, in

debate with his good friend 1rince 5al, the future Ring of ngland. 6fter a night of debauchery

together, he is imploring his young friend not to forget him when 5al becomes Ring. The banter

goes on, but the best part of it is =alsta@#s last few sentences on the matter $tal!ing about himself

here " his favorite subject'4

(ut to say % !now more harm in him than in myself,

were to say more than % !now. That he is old, the

more the pity, his white hairs do witness it* but

that he is, saving your reverence, a whoremaster,

that % utterly deny. %f sac! and sugar be a fault,

Eod help the wic!edT if to be old and merry be a

sin, then many an old host that % !now is damned4 if

to be fat be to be hated, then 1haraoh#s lean !ine

are to be loved. -o, my good lord* banish 1eto,

banish (ardolph, banish 1oins4 but for sweet Bac!

=alsta@, !ind Bac! =alsta@, true Bac! =alsta@,

valiant Bac! =alsta@, and therefore more valiant,

being, as he is, old Bac! =alsta@, banish not him

thy 5arry#s company, banish not him thy 5arry#s

company4 banish plump Bac!, and banish all the world.

The speech is quite a ramble, flled with =alsta@#s lively good spirits. 5ow can the 1rince follow

this& 5e does, with two little sentences4

% do. % will.

6nd there you have it. The prince !nows he must someday, soon, renounce his life with =alsta@

and turn to the responsibilities of ruling ngland. 6ll the !inetic energy of =alsta@, manifested in

the turns of phrase and rhythm in this speech, has been dammed up, thwarted and turned bac! by

those two little sentences, four little words.

That#s what variety of sentence length can do. Ereat e.pansiveness followed up by the bullwhip

crac! of a one-liner. %t#s not that one !ind of sentence is better than the other $although the taste

of the twentieth-century reader generally favors the terse, the economical'. %t#s just that there are

two di@erent !inds of energies here, both potent. Ose them both, and your prose will be energiAed.

The trouble is that many writers, unsure of themselves, are leery of long sentences because they

fear the run-on, that troll under the bridge, forgetting that it is often better to ris! imperfection

than boredom.

+hat we need, then, is practice in handling long sentences. %t is relatively easy to feel confdent in

writing shorter sentences, but if our prose is made up entirely of shorter structures, it begins to

feel li!e ,See 0ic! run. See Bane jump. See Bane jump on 1u@., 1rimer style $pronounced ,primmer,

in the O.S.6.', it#s called, and it would drive a reader craAy after a while.

-un7ons and $ength

=irst, review the section of the Euide that defnes -un7on 1entences. Cemember that a really

long sentence and a run-on sentence are not the same thing. Boseph +illiams#s fne boo! Style:

'oward #larity and "race $Oniv. of 3hicago4 FGGU', enlists this monster of a sentence from Thomas

5oo!er, father of 6merican democracy and founder of 5artford, 3onnecticut4

-ow if nature should intermit her course and leave altogether, though it were but for awhile, the

observation of her own laws* if those principal and mother elements of the world, whereof all

things in this lower world are made, should lose the qalities which now they have* if the frame of

that heavenly arch erected over our heads should loosen and dissolve itself* if celestial spheres

should forget their wonted motions, and by irregular volubility turn themselves any way as it might

happen* if the prince of the lights of heaven which now as a giant doth run his unwearied course,

should, as it were through a languishing faintness, begin to stand and to rest himself* if the moon

should wander from her beaten way, the times and seasons of the year blend themselves by

disordered and confused mi.ture, the winds breathe out their last gasp, the clouds yield no rain,

the earth be defeated of heavenly in?uence, the fruits of the earth pine away as children at the

withered breasts of their mother no longer able to yield them relief " what would become of man

himself, whom these things now do all serve&

"from -f the 0aws of Ecclesiastical Polity

The modern reader might rebel at the comple.ity of those clauses piled one upon the other, and it

does seem rather ponderous at frst. %n fact, if you were to write such a sentence in academic

prose, your instructor would probably call you in for a conference. (ut if, as reader, you let yourself

go a bit, there#s a well earned delight in fnding yourself at the end of such a sentence, having

successfully navigated its shoals. 6nd, as writer $avoiding such e.tremes', there#s much to be

learned by devising such monsters and then cutting them bac! to reasonable siAe.

5ere are some hints about using long sentences to your advantage. The ideas here are based

loosely on those in +illiams# boo!, which we highly recommend, but with our own e.amples.

Coordination

6llow the comple.ity of a longer sentence to develop after the verb, not before it. 3lic! .E-E to

read a MKG-word sentence $not a run-on, though' that succeeds grammatically but fails stylistically

because it does way too much wor! before the subject-verb connection is made. Ma!e the

connection between subject and verb quic! and vigorous and then allow the sentence to do some

e.tra wor!, to cut a fancy fgure or two. %n the completer $predicate', however, be careful to

develop the comple. structures in parallel form.

3lic! .E-E to visit our section on parallel form, most of which is ta!en from

+illiam Strun!#s Elements of Style. (e sure to go through our ,slide show,

on the Eettysburg 6ddress and closely e.amine the uses of parallelism in

that classic speech.

-epeated +erms

)ne of the scariest techniques for handling long sentences is the repetition of a !ey term. %t feels

ris!y because it goes against the grain of what you#ve been taught about repetition. +hen properly

handled, though, repetition of !ey words and phrases within a sentence and then within a

paragraph not only holds things together but creates a rhythm that provides energy and drives the

meaning home.

The Swiss watchma!ers# failure to capitaliAe on the invention of the digital timepiece was both