Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ethical Evaluation by Consumers

Hochgeladen von

Zeeshan Mateen0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

21 Ansichten16 Seitenethics

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenethics

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

21 Ansichten16 SeitenEthical Evaluation by Consumers

Hochgeladen von

Zeeshan Mateenethics

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 16

Ethical evaluation by consumers:

the role of product harm and

disclosure

Pi-Chuan Sun, Hsu-Ping Chen and Kuang-cheng Wang

Department of Business Management, Tatung University, Taipei, Taiwan

Abstract

Purpose The purpose of this paper is to explore the impacts of product harm, consumers product

knowledge and rms negative information disclosure on ethical evaluation of a rm, especially, the

moderating effects of product knowledge and negative information disclosure.

Design/methodology/approach A 3 2 2 between-subject design with three levels of product

harm, two levels of product knowledge, and two treatments of negative information was used in this

study. The experimental product is diet food.

Findings The ndings reveal that the level of product harm affects consumers ethical evaluation.

Furthermore, the individuals ethical evaluation will inuence his or her purchase intention. The main

effect of subjective knowledge is signicant while its moderating effect is not signicant. It is also

found that the negative information disclosure will lower consumers ethical evaluation of a rm, and

the effect of product harm on ethical evaluation will be stronger for harmful products than for

harmless products when the negative information is disclosed.

Practical implications Marketers might need to be especially responsive if their practices result

in a diminished reputation for their rms and lost sales. Exploiting the vulnerability of consumers or

worsening their situation by marketing harmful products might be evaluated as unethical under

principles of justice. It is suggested that marketers include increased disclosures of actual product

harm levels relative to industry norms.

Originality/value Consumers product knowledge and rms negative information disclosure are

integrated into the model, exploring the effect of product harm on consumers ethical evaluation of a

rm and their moderating effects are discussed.

Keywords Consumer behaviour, Product attributes, Ethics, Food products, Purchase intention,

Ethical evaluation, Product harm, Product knowledge, Negative information disclosure

Paper type Research paper

1. Introduction

Early examinations of ethical behavior largely focused on the need to establish public

condence in such professions as the legal, medical, accounting, and marketing

communities. However, recent well-publicized national or international recalls of

ground beef and pet food have increased public awareness of food safety issues. The

2008 milk product recall further added to public concerns about food safety.

Food-related risks to the public health extend beyond those posed by naturally

occurring organisms or chemical residues left from production or processing. The key

ingredients in some of the new diet supplements may be just as dangerous. For

example, some over-the-counter diet pills, drawn from plant leaves and promoted in

many herbal diet remedies as a natural weight loss product, are not regulated and

can have safety problems of their own. Any product that is known to be unsafe and/or

unt for its intended use is a harmful product (Smith and Cooper-Martin, 1997).

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0007-070X.htm

BFJ

114,1

54

Received October 2009

Revised February 2010

June 2010

Accepted June 2010

British Food Journal

Vol. 114 No. 1, 2012

pp. 54-69

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited

0007-070X

DOI 10.1108/00070701211197365

Polonsky et al. (2003) introduced the concept of a harm chain to broaden the way in

which rms and public policy makers consider potential negative outcomes from

marketing activities. All those whom the rm impacts, either negatively or positively,

have the right to be considered in corporate decision-making (Polonsky and Ryan,

1996). Marketing of a harmful product to any group is generally considered to be

unethical despite the product category (Nwachukwu et al., 1997; Smith and

Cooper-Martin, 1997). Accordingly, a normative prescriptive framework for ethical

conduct on the part of the business community is vital and an adequate understanding

of ethical evaluation of corporate behaviors by consumers is imperative. The ethical

evaluation procedure suggests that consumers follow a four-step decision-making

process: the consumer must:

(1) First recognize a moral issue is present.

(2) Make the moral judgment.

(3) Establish moral intent.

(4) Engage in moral behavior.

Frameworks that describe ethical decision-making in marketing organizations provide

a solid foundation for understanding dimensions of ethical decision-making in sales

(Ferrell et al., 2007). Many researches focused on the effect of organizational factors on

ethical decisions (Bellizzi, 1995; Bellizzi and Norvell, 1991; Dubinsky and Ingram,

1984), on the individuals role (Barnett et al., 1994), or on both (Ferrell et al., 2007).

Nevertheless, their observations are viewed from the perspectives of marketing

organizations. For market-driven organizations, consumers perceptions are critical for

their success. Particularly, product-harm crises and product recalls have the potential

to damage carefully developed brand equity, spoil consumers quality perceptions,

tarnish a companys reputation, and lead to revenue and market share losses (Chen

et al., 2009). Indeed, some researchers examined the ethical evaluation on marketing

strategies from the perspectives of consumers. For example, Smith and Cooper-Martin

(1997) and Jones and Middleton (2007) explored the consumers ethical evaluations of

marketing strategies, focusing on the roles of product harm and consumer

vulnerability. However, if the consumer is unable to identify or incorrectly identies

either the level of product harm or the degree of consumer vulnerability, the consumer

may not even recognize that a moral issue is present, thus resulting in a awed ethical

evaluation process. Indeed, negative information will exert certain inuence on a

consumers attitude and cognition (Fiske, 1980; Herr et al., 1991). Nevertheless, two

people may have the same quantity of information and exhibit different performance

on product judgment and choice. It is the product knowledge that helps the individual

to evaluate product statement and product quality. However, the ethical issue was

seldom studied about consumers product knowledge and rms negative information

disclosure. Hence, this study, to make up for the shortcomings of past research, will

attempt to explore the effects of consumers product knowledge and rms negative

information disclosure in consumers ethical evaluation. In particular, efforts will be

made to examine the moderating effects of product knowledge and negative

information disclosure on the relationship between product harm and ethical

evaluation.

Ethical

evaluation of

consumers

55

2. Literature reviews and research hypotheses

2.1 Ethical evaluation

Two sets of experiences that may inuence how one perceives the business

environment might lie in the persons experiences as a consumer and as a citizen

(Allison, 1978; Bearder et al., 1983). These two sets of experiences may be exemplied

by the individuals attitudes as a consumer and his attitudes toward business in

general (Pettijohn et al., 2007). Ethical evaluation is based on moral philosophy

(Reidenbach and Robin, 1990). The ethical decision depends on individual moral

values, and the judgment of business activity is inuenced by his/her moral

philosophy. There are ve philosophy models for individual ethical decision-making,

including theories of justice, relativism, egoism, utilitarianism and deontology. Based

on these theories, a multidimensional ethics measure has been developed (Reidenbach

and Robin, 1990). Dimension one, labeled a moral equity dimension, focuses on

concepts of fairness and justice, while dimension two is a relativistic dimension which

captures the idea of cultural and traditional acceptance of an action. Finally, dimension

three, named the contractualism dimension, centers on the breach of an implied

contract. The moral equity dimension is broad-based. It relies heavily on lessons from

our early training that we receive at home regarding fairness, right and wrong as

communicated through childhood lessons of sharing, religious training, morals from

fairy tales and fables. The relativism dimension is more concerned with the guidelines,

requirements, and parameters inherent in the social/cultural system than with

individual considerations and can be acquired later in life. The contractualism

dimension is in keeping with the notion of a social contract between business and

society (Donaldson and Dunfee, 1994).

2.2 Product harm and ethical evaluation

The Code of Ethics of the American Marketing Association states that marketers should

conform to the basic rule of professional ethics not to do harm knowingly, and they

should offer products and services that are safe and t for their intended uses. Hence,

marketing activities could be criticized and evaluated as unethical when it involves

products perceived as harmful because of the marketers obligation to avoid causing

harm. Harmful products have been dened as any product that is known to be unsafe

and/or unt for its intended use. Much of the discussion of product safety in the literature

relates to physical harm. However, product harm includes economic harm and

psychological harm(Smith and Cooper-Martin, 1997). Society may viewsuch products as

differing in degrees of harm on a continuum that ranges from less harmful

(i.e. non-sin or guilty pleasures), to more harmful (i.e. lthy habits), to most

harmful (i.e. sinful or socially unacceptable) ( Jones and Middleton, 2007). The

product perceived to be more or less harmful depends on the level of a harmful attribute

in the product, such as the amount of nicotine in cigarettes (Smith and Cooper-Martin,

1997). The marketing environment may be hostile for products if they are considered to

be more or most harmful as evidenced by the organized opposition of social, religious,

political, and regulatory groups. This hostility occurs despite the fact that these socially

problematic products, though strictly regulated, are generally legal and highly desired

by certain customer segments (Davidson, 1996; Rotfeld, 1998). Firms can create value by

reducing harmful organizational activities or outcomes (Polonsky et al., 2003). Although

the process of evaluating the harmful impacts of marketing activities is complex

BFJ

114,1

56

(Carrigan, 1985), perceptions of product harm affect publics judgments of the ethics of

the strategy, which in turn inuence any behavioral response. Product harmfulness has a

signicant effect on ethical evaluations, and ethical concern is partly due to perceived

product harm(Smith and Cooper-Martin, 1997). Generally, product harmappears to have

a greater effect on ethical evaluation than target vulnerability (Smith and Cooper-Martin,

1997; Jones and Middleton, 2007). Accordingly, this study infers that the level of product

harm will inuence consumers ethical evaluation of a rm. Based on the preceding

inference, H1 research hypothesis is proposed:

H1. The level of product harmwill inuence consumers ethical evaluation of a rm.

2.3 The effects of product knowledge on ethical evaluation

The measure of consumer product knowledge used in previous studies fall into three

categories: objective product knowledge, subjective knowledge, and experience-based

knowledge (Brucks, 1985). Subjective knowledge is an individuals perception of how

much he or she knows (Park and Lessig, 1981). Objective Knowledge is what an

individual actually has stored in memory ( Johnson and Russo, 1984). Experience-Based

knowledge is the purchasing or usage experience with the product. Consumers make

ethical evaluations of product harm based on information they remember (explicit

memory), information they know (implicit memory), or guess (Monroe and Lee, 1999).

Consumers with more product knowledge have better memory, recognition, analysis,

and logic abilities than those with less product knowledge. As a result, those who think

they have more product knowledge tend to rely on intrinsic cues, like the level of harmful

attribute in the product to evaluate a product because they are aware of the importance

of product information. On the other hand, those with less product knowledge are

inclined to use extrinsic cues, like the price or the brand, to evaluate a product since they

do not know how to judge it (Rao and Monroe, 1988). Accordingly, this study infers that

the consumers product knowledge will moderate the relationship between the level of

product harm and the ethical evaluation of a rm. Although there are three ways to

measure product knowledge, the product knowledge based on experience has less direct

relations with the behavior (Brucks, 1985). Moreover, the mechanisms through which

subjective knowledge and objective knowledge affect search (Brucks, 1985; Park and

Lessig, 1981) and information processing (Park et al., 1994) may be different. These two

knowledge constructs have been distinguished (Brucks, 1985; Park and Lessig, 1981),

because the consumers perceptions of what they know (subjective knowledge) and what

they really know (objective product knowledge) may be inconsistent. Therefore, the

moderating effects of two knowledge constructs are examined separately. Research

hypotheses H2 and H3 are then proposed.

H2. The effect of the level of product harm on ethical evaluation is contingent on

the consumers subjective product knowledge.

H3. The effect of the level of product harm on ethical evaluation is contingent on

the consumers objective product knowledge.

2.4 The effects of negative information disclosure on ethical evaluation

The general public does not normally know the average levels of product harm found

in many popular products. Firms typically do not provide that information, or the

government does not require that such information be printed on the packaging.

Ethical

evaluation of

consumers

57

Although consumers may want to purchase morally pleasing, socially acceptable, safe

products, often times they are not able to make informed judgments as to the true

nature of a product. Without the presence of a prime, subjects are far less likely to be

able to distinguish among high and low levels of product harm ( Jones and Middleton,

2007). While priming may alert the target to the products attributes, it may actually

cause them to more consciously and specically attend to the stimuli, thereby resulting

in more extreme responses (Martin, 1986). If no reference point is provided, the

consumer is less likely to accurately recognize the harm of a product. If consumers

cannot detect levels of product harm, they will be unable to detect a moral issue (Hunt

and Vitell, 1992; Paolillo and Vitell, 2002). If a rm disclosed the harmfulness

information associated with the product, it will provide a reference point and help

consumers to detect the levels of harmfulness and then inuence their attitudes and

cognition. Negative information will exert certain inuence on a consumers attitude

and cognition (Fiske, 1980; Herr et al., 1991). Hence, it is inferred that whether the

negative information is disclosed or not will moderate the effect product harm on

ethical evaluation. Based on the preceding inference, H4 research hypothesis is

proposed.

H4. The effect of the level of product harm on ethical evaluation is contingent on

whether the negative information is disclosed or not.

2.5 The effects of ethical evaluation on purchase intention

Purchase intention refers to the consumers subjective inclination towards a certain

product, and has been proven to be a key factor in predicting consumer behavior

(Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). People who evaluate a marketer as less ethical are to some

extent more predisposed to engage in disapproving behaviors (Andreasen and

Manning, 1990). Ethical concern evokes the likelihood of disapproving behaviors,

particularly boycotts and negative word of mouth (Smith and Cooper-Martin, 1997). A

consumer who evaluates a strategy as less ethical is more likely to engage in a

disapproving behavior (e.g. a boycott) and less likely to engage in an approving

behavior (e.g. the public could respond positively by praising a companys actions)

than is a consumer with a more ethical evaluation. These disapproving behaviors

appear to apply to all the companys products, not just the product in question. Such

disapproving behaviors can have powerful effects. Consumers perceptions of product

harmfulness are expected to affect their judgments of the ethicality of the marketer,

which in turn inuence their subjective inclinations towards that product. Purchase

intention is a consequent result of ethical evaluation. Accordingly, research hypothesis

H5 is proposed.

H5. A consumers ethical evaluation of a rm will inuence his/her purchase

intention.

3. Research method

This study examines the effects of product harm (harmless, less harmful, and more

harmful), product knowledge (low and high), negative information (disclosure and

undisclosure) on ethical evaluation. Especially, it tries to explore the moderating effects

of product knowledge and negative information on the relationship between product

harm and ethical evaluation. Figure 1 shows the research framework.

BFJ

114,1

58

3.1 Measurement

Following the methods used by Smith and Cooper-Martin (1997), product harm was

manipulated as the level of a harmful attribute (senna in diet food: none, 8 mg and

12 mg per unit). Each level of product harm was representative of high and low

amounts of the attribute offered to consumers. Product knowledge is dened as

consumers familiarity, expertise, and experience when a particular product is used or

purchased (Alba and Hutchinson, 1987). Primarily, we drew items from existing scales

and adapted them to reect consumer-specic knowledge of diet food. The scale

developed by Brucks (1985) was modied according to professional medical reports

and pretest. Eight items were used to evaluate the degree of consumers subjective

product knowledge and twelve items were used to measure objective knowledge.

Modied Multi-dimensional Ethics Scale (MES) (Reidenbach and Robin, 1990; Jones

and Middleton, 2007) was employed as a means for measuring general public potential

consumers ethical evaluations of company actions. A set of eight items resulting in a

three-dimensional scale was used. These three-dimensions do reect a generalized

evaluative structure (Humphreys et al., 1993). The moral equity dimension is intended

to measure the value sets thought to be imparted through the training and education

received in childhood. Subjects perceptions of moral equity (i.e. just/unjust,

fair/unfair, morally right/not morally right, and acceptable/not acceptable to my

family) were assessed. The relativism dimension is purported to measure the ethical

boundaries inherent in an individuals social system. This acculturation process is

often described as collective mental programming, such that each culture denes for its

members actions and behaviors that are morally acceptable or unacceptable

(i.e. culturally acceptable/unacceptable and traditionally acceptable/unacceptable)

(Hofstede, 1983). Finally, the contractualism dimension assesses the social contract

inherent between business and society-at-large (i.e. violates/does not violate an

unspoken promise and violates/does not violate an unwritten contract) (Reidenbach

and Robin, 1990). All items were anchored by a ve-point Likert scales.

Purchasing intention is denes as the possibility to make a purchase (Dodds et al.,

1991). Three items were used to measure it (consider buying, be likely to purchase, and

have willingness to buy). A ve-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to

strongly agree (1 strongly disagree, 5 strongly agree) was adopted. Finally,

negative information disclosure was operationalized as providing unfavorable

Figure 1.

Research framework

Ethical

evaluation of

consumers

59

information about the harmful attribute of diet food or not. Anote labeled When taken

in large amounts, senna side effects can include nausea, diarrhea, and severe cramps

will be presented as negative information disclosure. Otherwise, it is negative

information undisclosure.

A pilot test was conducted to clarify the measurement item of product knowledge,

ethical evaluation, and purchase intention as well as to examine measurement reliability.

Of 60 questionnaires 48 were completed and found valid. All the Cronbachs a coefcient

for each research construct are over 0.7, indicating a high internal consistency. The items

of subjective and objective product knowledge for the experimental product were also

tested. The result shows that the subjective and objective knowledge measurement items

can distinguish the level of product knowledge.

3.2 Data collection

A 3 2 2 between-subject design with three levels of product harm (harmless, less

harmful, and more harmful), two levels of subjective (or objective) product knowledge

(high and low), and two treatments of negative information (disclosure and

undisclosure) was used in this study. It could not only measure the main effects, but

also measure the interaction effects of variables. The experimental product was diet

food. Six situations were designed according to two manipulated variables, the level of

product harm (harmless, less harmful and more harmful) and negative information

disclosure (disclosure and undisclosure). Every situation was described by words and

pictures.

The rst part of the questionnaire was the picture and the description of the diet

food, herbal tea. Each subject was required to read one of the six descriptions of the

product rst randomly. After reading the description of the diet food, the subject was

asked to respond to the items on ethical evaluation and purchase intention. The third

part was the test of the subjects product knowledge, including subject and objective

knowledge. Finally, the subjects were asked to complete the demographic data.

There were six situations depicted verbally and pictorially. Because females are

usually the primary users of diet product, this research targeted female consumers as

the experiment unit. Three hundreds questionnaires (50 for each situation) were

delivered to ofce ladies in Taipei city by convenient sampling, of which 192 out of 198

returned were effective. The effective response rate was 62 per cent. Most of the

respondents (65.2 per cent) were under 30 years old, and more than half (53.6 per cent)

were university educated. Approximately 45.3 per cent of the participants worked in

the service sector, and 39.4 per cent of them were married. Approximately 64.6 per cent

of the participants had an annual income of under US$20,000 and 22.4 per cent between

US$20,000 and US$30,000.

3.3 Reliability and validity test

The test of internal consistence of each construct shows that all the Cronbachs a value of

each scale is greater than the suggested value of 0.7. Further, AMOS 7.0 was used to

examine measurement model. Results of the measurement model for intravenous

variables moral equity, relativism, contractualism, and purchase intention were

analyzed. The model shows adequate t: x

2

66:126 p 0:00, x

2

=df 1:787 (less

than 2), GFI 0.970, AGFI 0.947, CFI 0.998, TLI 0.997, and the RMSEA 0.045

(below 0.05). All the coefcients of each item are greater than 0.882 and are signicant at

BFJ

114,1

60

the level of 0.001. To test the discriminate validity, the condent interval of correlation

for each pair of latent constructs was examined. The result shows that there is

satisfactory discriminate validity for these theoretical constructs.

4. Result of hypothesis test

SPSS14.0 was used to process collected data and MANOVA was conducted to test the

hypotheses of this study. The results of testing are shown in Table I.

Table I shows the main and interaction effects of product harm, negative

information disclosure and subjective knowledge on ethical evaluation. It is found that

the main effect of product harmis signicant for moral equity (F 418.905, p 0.000),

relativism (F 275.558, p 0.000), and contractualism (F 323.957, p 0.000). The

main effect of negative information disclosure is signicant for moral equity

(F 160.972, p 0.000), relativism (F 146.968, p 0.000), and contractualism

(F 86.708, p 0.000). The main effect of subjective knowledge is signicant in moral

equity (F 5.101, p 0.025), relativism (F 12.808, p 0.000), and contractualism

(F 5.989, p 0.015). There is a signicant interaction effect between product harm

and negative information disclosure on moral equity (F 86.987, p 0.000),

relativism (F 75.044, p 0.000), and contractualism (F 145.267, p 0.000).

4.1 Product harm effects

Table I indicates that the main effect of product harm is signicant for moral equity,

relativism, and contractualism. A Shelf test was further conducted to examine the

Source Dependent variable DF F-value Sig.

Product harm (A) Moral equity 2 418.905 0.000

* *

Relativism 2 275.558 0.000

* *

Contractualism 2 323.957 0.000

* *

Purchase Intention 2 163.145 0.000

* *

Negative information (B) Moral Equity 1 160.972 0.000

* *

Relativism 1 146.968 0.000

* *

Contractualism 1 86.708 0.000

* *

Purchase intention 1 52.391 0.000

* *

Subjective knowledge (C) Moral equity 1 5.101 0.025

*

Relativism 1 12.808 0.000

* *

Contractualism 1 5.989 0.015

*

Purchase intention 1 1.769 0.185

A B Moral equity 2 86.987 0.000

* *

Relativism 2 75.044 0.000

* *

Contractualism 2 145.267 0.000

* *

Purchase intention 2 28.107 0.000

* *

A C Moral equity 2 1.204 0.302

Relativism 2 1.638 0.197

Contractualism 2 2.391 0.094

Purchase intention 2 2.502 0.085

Note:

*

p , 0.05,

* *

p , 0.01

Table I.

MANOVA analysis result

Ethical

evaluation of

consumers

61

effect of product harm. The results are shown in Table II. All the mean scores of moral

equity, relativism, and contractualism for harmless product are higher than those for

the less and more harmful products, while all the ethical evaluations for the less

harmful product are better than those for the more harmful product. The statistics bear

out that product harm erodes the rms ethical evaluation. H1 is supported.

4.2 The effect of product knowledge

Table I shows that the main effect of subjective knowledge is signicant in moral

equity, relativism, and contractualism. This study further examines the effect of

product knowledge by dividing the sample into two groups based on the level of

subjective knowledge. The result is shown in Table III. The mean scores of moral

equity, relativism and contractualism for the respondents with less subjective

knowledge are higher than those with more subjective knowledge, signifying that

consumers subjective knowledge reduces the rms ethical evaluation.

(I) Product harm ( J) Product harm (I-J) Mean difference Std. error Sig.

Moral equity Harmless Less 8.81558 0.31723 0.000

*

More 10.596 0.3244 0.000

*

Less Harmless 28.8155 0.31723 0.000

*

More Harmless

Less

210.5968 0.32447 0.000

*

2 1.7813 0.31723 0.000

*

Relativism Harmless Less 7.73346 0.34777 0.000

*

More 9.580 0.35571 0.000

*

Less Harmful 27.7334 0.34777 0.000

*

More 1.8472 0.34777 0.000

*

More Harmless 29.5806 0.35571 0.000

*

Less 2 1.8472 0.34777 0.000

*

Contractualism Harmless Less 5.82315 0.23691 0.000

*

More 7.193 0.24231 0.000

*

Less Harmless 25.8231 0.23691 0.000

*

More 1.3705 0.23691 0.000

*

More Harmless 27.1935 0.24231 0.000

*

Less 2 1.3705 0.23691 0.000

*

Note:

*

p , 0.01

Table II.

Results of shelf test for

product harm effects

Low-subjective

knowledge

High-subjective

knowledge

Mean Std. error Mean Std. error Sig.

Moral equity 12.408 0.236 10.758 0.165 0.000

*

Relativism 12.831 0.259 10.700 0.180 0.000

*

Contractualism 8.289 0.177 6.762 0.123 0.000

*

Note:

*

p , .05

Table III.

Main effect of consumers

subjective knowledge

BFJ

114,1

62

Table I reveals that there is no signicant interaction between product harm and

subjective knowledge. Subjective knowledge does not inuence the relationship

between product harm and ethical evaluation. H2 is not supported. Furthermore, this

study duplicated the analysis by replacing subjective knowledge with objective

knowledge. The results show that both the main effect and interaction effect of

objective knowledge are not signicant for moral equity, relativism, and

contractualism. H3 is not supported.

4.3 The effect of negative information disclosure

Table I shows that negative information disclosure has a signicant main effect on

moral equity (p , 0:01), relativism (p , 0:01), and contractualism (p , 0:01), and there

is a signicant interactive effect between product harm and negative information

disclosure. The interaction effect was further examined. Figure 2 shows the interactive

effect of product harm and negative information disclosure on moral equity. Figure 3

shows the interactive effect of product harm and negative information disclosure on

relativism. Figure 4 shows the interactive effect of product harm and negative

information disclosure on contractualism. The three analyses reveal that the effect

from product harm on ethical evaluations is stronger when negative information is

disclosed. It means that the effect of product harm hinges on whether the negative

information is disclosed or not. H4 is supported.

Figure 2.

The interaction of product

harm and negative

information on the moral

equity

Figure 3.

The interaction of product

harm and negative

information on the

relativism

Ethical

evaluation of

consumers

63

4.4 The effect of ethical evaluation on purchase intention

A regression analysis was then conducted through SPSS14.0 to examine the

relationship between consumers ethical evaluation and purchase intention. The results

reveal that the positive effects of moral equity (b 0.658, t 6.825, p 0.000) and

contractualism (b 0.147, t 2.199, p 0.029) on purchase intention are signicant.

However, the positive effect from relativism is not signicant (b 0.114, t 1.270,

p 0.205). A consumers purchase intention is inuenced by his or her evaluation of a

rms moral equity and contractualism but not by relativism. Table IV provides the

evidence that H5 is partially supported.

5. Conclusions

Based on previous researches, this study examines the effects of product harm on

ethical evaluation. Different from the previous researches, this study also investigates

the effects of consumers product knowledge and negative information disclosure. In

particular, the moderating effects of product knowledge and negative information

disclosure on the relationship between product harm and ethical evaluation are also

explored. In addition, the current study links ethical evaluation and behavioral

intention since consumers perceptions will inuence their behaviors.

The ndings of this study reveal that consumers ethical evaluation of a harmless

product is better than that of a less harmful product or a more harmful product.

Product harmfulness has a signicant effect on ethical evaluation, and ethical concern

partly stems from perceived product harm (Smith and Cooper-Martin, 1997).

Furthermore, the individuals ethical evaluation will affect his or her purchase

intention. If a rm introduced a harmful product to the market, consumers will assign

Y

Purchase intention

X Beta t-value Sig.

Moral Equity 0.658 6.825 0.000

* *

Relativism 0.114 1.270 0.205

Contractualism 0.147 2.199 0.029

*

Note:

*

p , 0.05,

* *

p , 0.01

Table IV.

Results of regression

analysis

Figure 4.

The interaction of product

harm and negative

information on the

contractualism

BFJ

114,1

64

it a lower ethical rating. Perception of product harm affects a perspective customers

judgment of the ethics of the strategy, which in turn inuences any behavioral

response. The possibility of experiencing economic or physical harm downgrades

his/her ethical evaluation of the rm and then reduces his/her purchase willingness.

Consistent with the nding of Humphreys et al. (1993), the result of this study suggests

that the moral equity dimension exerts the greatest inuence impact in explaining

consumer intention. Thus, concepts of fairness and justice dominate consumers

behavioral intention.

It is found that the level of subjective knowledge inuences consumers ethical

evaluation of a rm. However, it does not inuence the relationship between the

product harm and ethical evaluation. The level of objective knowledge does not

inuence ones ethical evaluation, nor does it inuence the relationship between the

product harm and ethical evaluation. Consistent with the argument of Park and Lessig

(1981), subjective knowledge could be more helpful in understanding the formulation of

consumers decisions than objective knowledge, since subjective knowledge reects

the self-condence of product knowledge in their decisions. In this research, it is found

that subjective knowledge can affect ones ethical evaluation of a rm. Consumers with

high condence in understanding product may expect more of rms ethical behaviors,

and then lower their ethical evaluation of the rms.

The present study also nds that negative information disclosure will lower

consumers ethical evaluation. A product attribute cannot be evaluated since it carries

no information before disclosure (Carpenter et al., 1994). The disclosed information is a

cue for consumer evaluation. Especially, negative information is more attractive than

positive information. Consumers are more sensitive to negative information for

protecting themselves from being injured. Consequently, the effect of product harm on

ethical evaluation will be stronger from a harmful product than from a harmless

product when negative information is disclosed.

5.1 Managerial implications

For market-driven organizations, consumers perceptions are critical for their success.

All those whom the rm impacts, either negatively or positively, have the right to be

considered in corporate decision-making (Polonsky and Ryan, 1996). Consequently,

public condence in organizations, such as medical, accounting, and marketing

communities, is focused in researches related to ethical behavior (Smith and

Cooper-Martin, 1997). Nevertheless, American public condence in the safety of the

food supply fell in the period from August 2005 to June 2007. The proportion of the

population indicating that they were very condent about the safety of their food

dropped by eleven percentage points to 22 per cent and the proportion indicating that

they were not very condent rose by ve percentage points to 15 per cent (Stinson et al.

2008). During the past several years marketers have witnessed a growing concern for

and inquiry into the moral implications of marketing decision making (Reidenbach and

Robin, 1991). It is believed that in the long run a companys right to continue in

business is granted by the consumers they serve ( Jones and Middleton, 2007). This

study provides the evidence that product harm will affect consumers ethical

evaluation of the rm, and, in turn, affect consumers purchase intention. When levels

of product harm were manipulated in our studies, there was ethical concern about the

marketing of the more harmful product (Smith and Cooper-Martin, 1997). Consumers

Ethical

evaluation of

consumers

65

may want to purchase morally pleasing, socially acceptable, safe products. If a rm is

to maximize its prot potential, it must reconsider its actions if the product possesses a

certain level of actual harm.

Todays market is characterized by actively involved and sophisticated consumers.

It is found that consumers with high condence in understanding of product may

expect and demand more of a rms ethical behaviors, and then lower their ethical

evaluation of the rm. The publics ethical perceptions of business people in general

are commonly low (Pettijohn et al., 2007). Polonsky et al. (2003) suggested a broad

concept of harm chain to consider the potential negative outcomes from marketing

activities. Addressing harm from a harm chain perspective might require rms to alter

production inputs, redesign production process or consider leaving the community or

industry. For food safety, manufacturers are considered more responsible for food

defense than other segments of the food industry or consumers. Manufacturers are

clearly believed to be primarily responsible for food defense, and the percentage

assigning manufacturers primary responsibility grew over the time (Stinson et al.,

2008). Todays consumers are much more knowledgeable about product offerings than

their predecessors. Marketers might need to be especially responsive if their practices

result in a diminished reputation for the rm and lost sales. Nevertheless, consumers

with less knowledge are liable to give higher scores in ethical evaluation even though

having purchased harmful products.

If consumers are unable to accurately detect product harm levels, they may be

putting themselves at risk by not taking necessary precautions to avoid or minimize

the potential risk posed by the product. It would be reasonable to assume that a

consumer would take added precautions to avoid negative outcomes associated with

products perceived to incur greater physical, emotional, or nancial risk. If the

consumer is unable to detect the inherent added risk from a highly harmful product, he

is unlikely to be proactive in minimizing or at least consciously accepting the added

risk. Exploiting the vulnerability of consumers or worsening their situation by

marketing harmful products might be evaluated as unethical under principles of

justice. This may become particularly controversial if consumers are indeed unable to

fully comprehend the level of actual harm associated with a product when making

judgments about these types of products ( Jones and Middleton, 2007). Firms knowing

that consumers are unable to identify the added risk associated with their products

may nd themselves bearing increased liability if actual harm to the consumer results.

It is suggested that marketers should disclose the level of actual product harm and its

side effects. Providing important information, such as the side effects of diet food, can

help consumers understand the risks associated with their decisions. In fact, rms and

organizations are not the only members of the exchange that initiate harm. Consumers

may also cause harm via inappropriate product use (Polonsky et al., 2003). Of course,

the disclosure of negative information may make consumers speculate that the side

effects of this ingredient are serious that the rm had no other choice but to disclose it

to reduce potential impact. In other words, the consumers are likely to interpret

disclosure of negative information as a signal of escaping from legal liability.

Therefore, it worsens ethical evaluation when selling a harmful product. Nevertheless,

a proactive strategy may have positive consequences on consumer perceptions. For

example, such a strategy can be interpreted as an indication that the rm is

trustworthy and cares about its consumers (Chen et al., 2009). Short-run oriented

BFJ

114,1

66

businesses which only care about making prots will be punished by their customers

because, in the long run, a companys right to continue in business is granted by the

consumers it serves ( Jones and Middleton, 2007).A growing body of literature has

argued that there is a positive link between rms socially responsible strategies and

their nancial market performance (Margolis et al., 2007).

5.2 Limitations and suggestions for future research

Several avenues for future research can be suggested that would extend the ndings of

this research. Although female consumers are suitable to be the study subjects due to

their greater familiar with and more frequent use of the products selected in this study,

the results of this study may not generalize to their male counterparts. Furthermore,

since this research targeted the ofce ladies in Taipei city by convenient sampling, the

sampling bias should be taken into account. Future research may consider people in

other lines of work as subjects or adopt probability sampling to enhance external

validity. In the course of the experiment, the subjects only read product information

described verbally or pictorially. Future study may provide real products to enhance

the reality of the experimental context. This study considers only product knowledge

and negative information as moderating variables. Further study can include more

other variables to examine the effects of product harm on the basis of ethical

evaluation.

References

Alba, J.W. and Hutchinson, W. (1987), Dimensions of consumer expertise, Journal of Consumer

Research, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 411-54.

Allison, N.K. (1978), A psychometric development of a test for consumer alienation from the

marketplace, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 564-75.

Andreasen, A.R. and Manning, J. (1990), The dissatisfaction and complaining behavior of

vulnerable consumers, Journal of Consumer Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction and Complaining

Behavior, Vol. 3, pp. 12-20.

Barnett, T., Bass, K. and Brown, F. (1994), Ethical ideology and ethical judgments regarding

ethical issues in business, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 13, June, pp. 469-80.

Bearder, W.O., Lichtenstein, D.R. and Teel, J.E. (1983), Reassessment of the dimensionality,

internal consistency, and validity of the consumer alienation scale, in Murphy, P.E. et al.

(Eds), 1985 American Marketing Association Summer Educators Conference Proceedings,

American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL, pp. 35-40.

Bellizzi, J.A. (1995), Committing and supervising unethical sales force behavior: the effects of

victim gender, victim status, and sales force motivational techniques, Journal of Personal

Selling and Sales Management, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 1-15.

Bellizzi, J.A. and Norvell, D.W. (1991), Personal characteristics and salespersons justications

as moderators of supervisory discipline in cases involving unethical salesforce behavior,

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 11-16.

Brucks, M. (1985), The effect of product class knowledge on information search behavior,

Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 12 No. 1, pp. 1-16.

Carpenter, G.S., Rashi, G. and Nakamoto, K. (1994), Meaningful brands from meaningless

differentiation, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 339-50.

Ethical

evaluation of

consumers

67

Carrigan, M. (1985), Positive and negative aspects of the societal marketing concept: stakeholder

conicts for the tobacco industry, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 11 No. 5,

pp. 469-85.

Chen, Y., Ganesan, S. and Liu, Y. (2009), Does a rms product-recall strategy affect its nancial

value? An examination of strategic alternatives during product-harm crises, Journal of

Marketing, Vol. 73 No. 6, pp. 214-26.

Davidson, D.K. (1996), Selling Sin: The Marketing of Socially Unacceptable Products, Quorum

Books, Westport, CT.

Dodds, W.B., Monroe, K. and Grewal, D. (1991), Effect of price, brand and store information on

buyers product evaluations, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 307-19.

Donaldson, T. and Dunfee, T.W. (1994), Toward a unied conception of business ethics:

integrative social contracts theory, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 19 No. 4,

pp. 252-84.

Dubinsky, A.J. and Ingram, T.N. (1984), Correlates of salespeoples ethical conict: an exploratory

investigation, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 3, November, pp. 343-53.

Ferrell, O.C., Johnston, M.W. and Ferrell, L. (2007), A framework for personal selling and sales

management ethical decision making, Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management,

Vol. 27 No. 4, pp. 291-9.

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975), Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to

Theory and Research Reading, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Fiske, S.T. (1980), Attention and weight in person perception: the impact of negative and

extreme behavior, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 38 No. 6, pp. 889-906.

Herr, P.M., Kardes, F.R. and Kim, J. (1991), Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute

information on persuasion: an accessibility perspective, Journal of Consumer Research,

Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 454-62.

Hofstede, G. (1983), The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories, Journal of

International Business Studies, Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 75-89.

Humphreys, N., Robin, D.P., Reidenbach, R.E. and Moak, D.L. (1993), The ethical decision

making process of small business owner/managers and their customers, Journal of Small

Business Management, Vol. 31, July, pp. 9-22.

Hunt, S.D. and Vitell, S. (1992), A general theory of marketing ethics: a retrospective and

revision, in Quelch, J. and Smith, S. (Eds), Ethics in Marketing, Irwin, Chicago, IL.

Johnson, E.J. and Russo, J.E. (1984), Product familiarity and learning new information, Journal

of Consumer Research, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 542-50.

Jones, J.L. and Middleton, K.L. (2007), Ethical decision-making by consumers: the roles of

product harm and consumer vulnerability, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 70 No. 3,

pp. 247-64.

Margolis, J.D., Elfenbein, H. and Walsh, J. (2007), Does it Pay to be Good? A Meta-analysis and

Redirection of Research on Corporate Social and Financial Performance, Harvard Business

School, Harvard University, Boston, MA.

Martin, L.L. (1986), Set/reset: use and disuse of concepts in impression formation, Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 51 No. 3, pp. 493-504.

Monroe, K.B. and Lee, A.Y. (1999), Remembering versus knowing: issues in buyers processing

of price information, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 27 No. 2,

pp. 207-25.

BFJ

114,1

68

Nwachukwu, S.L.S., Vitell, S.J., Gilbert, F.W. Jr and Barnes, J.H. (1997), Ethics and social

responsibility in marketing: an examination of the ethical evaluation of advertising

strategies, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 39 No. 2, pp. 107-18.

Paolillo, J. and Vitell, S. (2002), An empirical investigation of the inuence of selected personal,

organizational, and moral intensity factors on ethical decision making, Journal of

Business Ethics, Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 65-74.

Park, C.W. and Lessig, V.P. (1981), Familiarity and its impacts on consumer decision biases and

heuristics, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 223-30.

Park, C.W., Feick, W.L. and Mothersbaugh, D.L. (1994), Consumer knowledge assessment,

Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 71-82.

Pettijohn, C.E., Pettijohn, L.S., Pettijohn, J.B. and Taylor, A.J. (2007), How do the attitudes of

students compare with the attitudes of salespeople? A comparison of perceptions of

business, consumer and employer ethics, Marketing Management Journal, Vol. 17 No. 1,

pp. 51-64.

Polonsky, M.J. and Ryan, P. (1996), The implications of stakeholder statutes for socially

responsible managers, Business and Professional Ethics Journal, Vol. 15 No. 4.

Polonsky, M.J., Carlson, L. and Fry, M.-L. (2003), The harm chain: a public policy development

and stakeholder perspective, Marketing Theory, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 345-64.

Rao, A.R. and Monroe, K.B. (1988), The moderating effect of prior knowledge on cue utilization

in product evaluations, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 253-64.

Reidenbach, R.E. and Robin, D.P. (1990), Toward the development of a multidimensional scale

for improving evaluations of business ethics, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 9 No. 8,

pp. 639-53.

Reidenbach, R.E. and Robin, D.P. (1991), Epistemological structures in marketing: paradigms,

metaphors, and marketing ethics, Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 185-200.

Rotfeld, H. (1998), Marketing is target when product undesirable, Marketing News, Vol. 32

No. 18, p. 8.

Smith, N.C. and Cooper-Martin, E. (1997), Ethics and target marketing: the role of product harm

and consumer vulnerability, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 61 No. 3, pp. 1-20.

Stinson, T.F., Fhosh, D., Kinsey, J. and Degeneffe, D. (2008), Do household attitudes about food

defense and food safety change following highly visible national food recalls?, American

Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 90 No. 5, pp. 1272-8.

Corresponding author

Pi-Chuan Sun can be contacted at: pcsun@ttu.edu.tw

Ethical

evaluation of

consumers

69

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com

Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Effects of Unethical ConductDokument16 SeitenThe Effects of Unethical ConductZeeshan MateenNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Consumer Personality and Green Buying IntentionDokument15 SeitenConsumer Personality and Green Buying IntentionZeeshan MateenNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

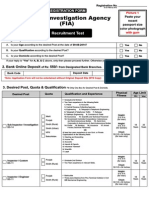

- FIA Aug2014 FormDokument5 SeitenFIA Aug2014 FormZeeshan MateenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Norm - Referenced Tests & Criterion-Referenced TestsDokument13 SeitenNorm - Referenced Tests & Criterion-Referenced TestsZeeshan Mateen100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Child Protection 24aug2014 FormDokument5 SeitenChild Protection 24aug2014 FormAd ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- B Plan of CanteenDokument36 SeitenB Plan of CanteenZeeshan MateenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Music Lesson PlanDokument15 SeitenMusic Lesson PlanSharmaine Scarlet FranciscoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Have To - Need To - Want To - Would Like To... Lesson PlanDokument1 SeiteHave To - Need To - Want To - Would Like To... Lesson Planped_inglesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Pallasmaa - Identity, Intimacy And...Dokument17 SeitenPallasmaa - Identity, Intimacy And...ppugginaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- CV Summary for Ilona Nadasdi-NiculaDokument3 SeitenCV Summary for Ilona Nadasdi-NiculaCarmen ZaricNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sentence WritingDokument2 SeitenSentence WritingLee Mei Chai李美齊Noch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Consumer and Business Buyer BehaviorDokument50 SeitenUnderstanding Consumer and Business Buyer BehavioranonlukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Linking Words and ConnectorsDokument2 SeitenLinking Words and ConnectorsGlobal Village EnglishNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Bequest of Love: Hope of My LifeDokument8 SeitenBequest of Love: Hope of My LifeMea NurulNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Sbarcea Gabriela - Message To My Butterfly PDFDokument300 SeitenSbarcea Gabriela - Message To My Butterfly PDFVioricaSbarceaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Management Extit Exam Questions and Answers Part 2Dokument8 SeitenManagement Extit Exam Questions and Answers Part 2yeabsrabaryagabrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mr Collins' proposal rejectedDokument5 SeitenMr Collins' proposal rejectedabhishek123456Noch keine Bewertungen

- Transactional AnalysisDokument32 SeitenTransactional AnalysisAjith KedarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minggu 2: Falsafah Nilai & EtikaDokument12 SeitenMinggu 2: Falsafah Nilai & EtikaNur Hana SyamsulNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - Looking at Language Learning StrategiesDokument18 Seiten1 - Looking at Language Learning StrategiesTami MolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Sample TechniquesDokument3 SeitenSample TechniquesAtif MemonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Wisc V Interpretive Sample ReportDokument21 SeitenWisc V Interpretive Sample ReportSUNIL NAYAKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Based LearningDokument1 SeiteProject Based Learningapi-311318294Noch keine Bewertungen

- Vistas Book Chapter 4 The EnemyDokument13 SeitenVistas Book Chapter 4 The EnemySeven MoviesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- PSY285 Assign 2 Lin Y34724878Dokument10 SeitenPSY285 Assign 2 Lin Y34724878Hanson LimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cornelissen (5683823) ThesisDokument48 SeitenCornelissen (5683823) ThesisAbbey Joy CollanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Media MarketingDokument11 SeitenSocial Media MarketingHarshadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Play TherapyDokument26 SeitenPlay TherapypastellarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Benchmarking Clubs: A Guide For Small and Diaspora NgosDokument7 SeitenBenchmarking Clubs: A Guide For Small and Diaspora NgosEngMohamedReyadHelesyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coxj Ogl321 Mod1 Paper Final For 481Dokument5 SeitenCoxj Ogl321 Mod1 Paper Final For 481api-561877895Noch keine Bewertungen

- Take Control of Your Mental, Emotional, Physical and Financial DestinyDokument10 SeitenTake Control of Your Mental, Emotional, Physical and Financial DestinyGanti AranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 9 English DLL Q2 Lessons on Finding Others' GreatnessDokument136 SeitenGrade 9 English DLL Q2 Lessons on Finding Others' GreatnessPhranxies Jean BlayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2J Coordination: Time: 1 Hour 5 Minutes Total Marks Available: 65 Total Marks AchievedDokument26 Seiten2J Coordination: Time: 1 Hour 5 Minutes Total Marks Available: 65 Total Marks AchievedRabia RafiqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIGDAL State in Society ApproachDokument9 SeitenMIGDAL State in Society Approachetioppe100% (4)

- Principles of Management - PSOCCDokument32 SeitenPrinciples of Management - PSOCCEden EscaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 2 ReportDokument77 SeitenGroup 2 ReportZhelParedesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)