Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Chinese Business Groups

Hochgeladen von

92_883755689Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chinese Business Groups

Hochgeladen von

92_883755689Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

What has China done to promote big business groups? Are they paragons or parasites?

There has been significant change within Chinas large enterprises and groups, but until quite

recently these changes have remained poorly understood. Divergent views on this subject have

emerged. These competing views broadly correspond to the competing paradigms found in the

development literature. This split has emerged at least in part owing to the fact that among studies

related to Chinas economic development, because of a priori assumptions regarding key variables

determining enterprise performance, there has been a tendency to categorize and study enterprises

mainly from the perspective of different ownership types. Ownership and the distribution of

property rights have conventionally been considered one of the main determinants of economic

performance, particularly in economies undertaking the transition from plan to market. As a result

of this mindset there have been many studies looking at state owned enterprises (SOEs) as a whole

and also studies making comparisons between the state sector and the newer private sector.

Comparatively fewer studies, by contrast, have looked directly and exclusively at Chinas large-scale

sector or large enterprise groups. The important contribution and growing presence of large

enterprises, particularly large groups within key industries supported by specific state policies, has

therefore at times also been largely overlooked. Only a small (though growing) body of specialized

literature in Western academia investigating large enterprises and groups has emerged in the past

few years (Keister 1998; Lo 1997; Lo 1999; Lo and Chan 1998; Nolan 1996; Nolan and Wang 1998;

Smyth 2000). These studies have already strongly challenged some of the conventional insights on

Chinas industrial development. In particular, the generally negative assessment made of the overall

performance and importance of large-scale state industry, and the tendency to regard small

enterprises as engines or the foundation for recent economic growth, has been brought into

question (World Bank 1997: 21). Instead, an alternative and competing viewpoint, namely that

Chinas LMEs are now actually coming to represent the 'core' of Chinas transformed economy, is

gaining ground.

[3] By 1997 there were 468,000 enterprises in the industrial independent accounting category. The

number of LMEs increased in this period markedly, from approximately 5,000 to 24,000, up from 1.3

per cent to 3.9 per cent of the total number of all independent accounting industrial enterprises.

. The report shows that to succeed the encouragement strategy needs to be accompanied by a

strategy of discipline; that is, policies that impose hard budget constraints on the old-large

enterprises that remain from pretransition days. Soft budget constraints that allow these enterprises

to not pay their taxes, social security contributions, and bank debts undermine the level playing field

between different kinds of enterprises and have also been at the root of explosive fiscal and banking

crises. The decentralization of management decisions boosted the productivity of firms. 25 But

relative to the rest of the economy, state industrial enterprises languished, with slow growth and

declining profits. In part this was because state enterprises, unlike their nonstate competitors, were

required to provide job security and a range of social services, such as housing, education, and

health care. Yet slackening performance also reflected a deeper malaise rooted in the poor

investment decisions of the past and in an "iron rice bowl" system that did not penalize low

productivity.

Policies promoting institutional change in the trial business groups

The previous sections have examined some of the features of the national team, including the

industries and provinces from which they developed, their origins and the origins of policies aimed

at promoting their development, the size of the groups and their strategic importance to the Chinese

economy. The next sections go on to look in more detail at policies introduced to the national team

trial groups in two important policy directives, central to understanding the current grasp the large,

let go of the small policy, issued in 1991 and 1997.27 Although the emergence of trials with groups

can be dated back to 1986, these two influential State Council policy directives, in which formal

selection of the trial groups was made, are still regarded as a a great leap forward in the

development of business groups (Chen Qiaosheng, 1998: 704). As already described, even before the

first batch of trial groups was officially chosen in 1991 five years of experimentation, consideration

and preparation concerned with the direction of business group policy had taken place. Dongfeng,

one of the very first trial enterprise groups, after several months was expanded to include two more

auto producers. Shortly after this, by April 1987 the number of trial groups had unofficially expanded

to 13 and the preferential planning policy was complemented with the promotion of internal group

finance companies. Over the years a number of new policies were introduced and spread to the trial

business groups, including foreign trade rights, standardization of the mother/son company system,

clarification of property rights within the core enterprises and promotion of technology centres.

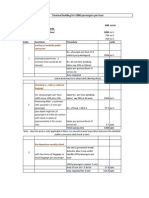

Table 3.4 illustrates the various measures, the timing of their introduction to the trial groups and the

way in which they gradually broadened their coverage. By 1999 the three trial groups had increased

to 120 and at least seven major policy measures had been introduced .

The first State Council directive, December 1991

The first directive laid out the objectives, principles of experimentation with groups and necessary

conditions for choosing the trial groups. Broadly speaking the policies introduced attempted to free

the enterprise groups from some of the constraints of the old planning system. This was partly

achieved by using the market mechanism to exploit their full potential but also by the introduction

of new rules and laws to promote necessary institutions and greater cohesion within the groups. In

total five interrelated goals for the national team enterprise groups are listed in this directive.

Firstly, and unsurprisingly, a priority was to encourage specialization and redress the historical legacy

of geographically dispersed small-scale industry and the inability of achieving economies of scale.

Secondly, the groups were seen as a means of breaking through the existing regional and

departmental barriers which constrained the natural growth of large-scale enterprise groups. This

remains a problem today: enterprise mergers are still hindered by regional and departmental

barriers. The government should guide the development of large enterprises by industrial policy but

not administrative intervention (CDBW, 8 December 1998). Thirdly, they were to give play to the

leading role of large enterprises in concentrating and directing investment funds in the hope of

reducing replication. Fourthly, even by 1991 it was hoped that international competitiveness could

be improved so the groups could become major forces in international markets.

The fifth and final objective was related to the domestic economy.This was to improve what are

referred to as macro-economic adjustment capabilities. This objective highlights the official

endorsement groups were given in absorbing enterprises in the small-scale state sector and loss

makers in general, a role they have assumed from early on in reforms. This policy clearly states that

by reforming a set of large enterprises as the core of the business groups it will be possible to more

efficiently lead the economic activities of a large number of medium and small sized enterprises. In

the 1994-97 period alone it is reported, for example, that profitable large groups saved about 2,000

loss-making enterprises (China Business Review, May-June 1999). The history of enterprise groups,

as already noted, is closely associated with that of merger and take-over, a process which in China

has usually involved loss-making enterprises. The groups, therefore, have explicitly been given a dual

role, one with inherent contradictions. They have been earmarked to lead the large-scale sector into

international markets but also to absorb large numbers of poorly performing small enterprises. This

dual function of enterprise groups continues to make them an appealing and natural policy for the

reform of state industry though it also brings into question whether they will be able to succeed in

achieving international levels of competitiveness.

The State Council envisaged several criteria the groups would need to fulfil in order to achieve the

foreseen goals. Firstly, a strong core member was needed, hence usually the agglomeration of the

groups around successful large state-owned enterprises. Secondly, a multi-layered structure was a

prerequisite for a large group company with the ability to lead smaller enterprises, increase scale

and become trans-regional. Thirdly, an integrated management system was needed, based around

capital ties between enterprises. Furthermore, the selection of groups was to correspond to

national economic development strategies and industrial policies. Trans-regional and departmental

groups were also encouraged as was their separation from governmental responsibilities. A key

feature of this policy were efforts to force the often disparate members of the enterprise groups

together into a cohesive organic whole by advocating the unification of the group led by the mother

company. To this end the policy of six unifications within the close layer of enterprises of the group

was promoted. This foresaw unifying the planning departments of the core members and developing

greater contractual relations within core enterprises. Unification of loans needed for large

infrastructure and technology projects, of imports and exports, integration of the main management

teams (giving responsibility of hiring and firing to the mother company) were other elements of the

six unifications policy. Eventual unification in the ownership of core members, to be supervised by

the State Capital Management Bureau, was also put forward and this led to the creation of a policy

which empowered groups with rights to manage state capital. The 1991 directive also gave details

of the single track which were expanded and clarified. To an extent this measure also contributed to

unification within the groups. Preferential planning only included the core enterprise and the close

layer of members but not semi-close and dispersed members. This created an incentive for

enterprises to enter the close layer of the groups. The development of finance companies promoting

the internal circulation of funds, and export and import rights allowing independent export and

import management, were also included in this directive.

The first State Council directive in 1991 outlined the reasons for forming business groups and some

of the policies that were to be used. It also chose the groups to be included in the trials. It marked an

important step in the development of an industrial strategy which had not yet fully crystallized. This

involved adopting measures to promote the institutional transformation of large-scale industry in

key industries while at the same time giving up control of the small-scale state industry.

The second State Council directive, 1997

After a gap of about five years on 29 April 1997 the second state directive was published and the

additional batch of 63 trial groups was added to the initial 57 groups. It deemed that the initial batch

had basically achieved the stated goals but stressed that a new phase had been entered. The new

policy, although pushing forward and recognizing many of the reforms initiated in the earlier

document, noted that two important changes had taken place. Firstly, the growth pattern had

transformed from extensive growth to concentrated growth, referring to the need to further focus

development in certain key areas of the economy. Secondly, it also stressed the implications of

further integration with the international economy: as opening to the outside continues enterprises

will face more severe domestic and international competition. Accordingly it was argued that a

crucial stage in reform had been entered in which two basic transformations, from extensive

development to intensive concentrated development within key industries, and from national to

international markets, were to be made. To achieve this, it concludes, deepening the trial work with

large enterprise groups is a vital necessity.

The five goals laid out in the later document are in many ways quite similar to those given in the

1991 document, though there are two noticeable differences. Firstly, an important position is given

to the establishment of the modern corporate system so that the groups and their members could

become defined legal entities. To this end it is noted that the direction of state enterprise reform is

the establishment of the modern corporate system, based upon Chinas company law, newly

established in 1994. Greater emphasis is also placed upon the separation of enterprise and

governmental activities and the transformation of government departments, making the groups

responsible for their debts as well as granting them rights to retain profits. Secondly, although the

role of groups in promoting macroeconomic stability and directing a large number of small

enterprises is not omitted entirely as a goal in this later document, it is only briefly mentioned in

passing. This signified the intention to move away from direct state intervention in the creation of

forced marriages. The second policy continued to attempt to concentrate greater powers within

the mother company. This was so they could formulate strategies for the groups and become the

leading providers of capital and technology, as well as co-ordinators of foreign investment and

technological exchanges within the groups. To this end the investment function of the mother

company was expanded, giving it greater freedom in co-ordinating new investment projects as well

as utilizing foreign capital for new projects below $30 million dollars. Domestic and international

stock market listings were also to be encouraged among the mother companies, as well as corporate

bond issues. Trade rights were also expanded to other members of the enterprise groups, creating

incentives for them to join. The creation of technology and research centres within the groups to

help promote their product development capabilities and hopes of being successful in the

international market place were also advanced.

The second State Council directive issued in 1997 recognized Chinas increasing international

economic integration and the need to further develop the framework within which large enterprises

operated. It recognized the need to further concentrate industry in certain sectors by creating larger

economic units more akin to large modern industrial corporations in developed nations. It expanded

the number of enterprises and the industries and regions they covered, it recognized also that large

enterprises could also be privately run, by including three TVEs. There were, therefore, a number of

important changes in the focus of policy in the second directive as well as the means by which the

goals could be achieved.

A number of trials were introduced in the groups: have these had an impact on performance?

Preferential planning status

The single track preferential planning policy was the first and perhaps single most important

measure introduced within the trial business groups. It enabled the emergence of the groups from

within the planning system and the beginning of their evolution into units more akin to enterprises.

For the first time it gave enterprises real autonomy in the most basic of decisions concerning areas

such as product output volume, basic construction and investment, foreign technology use, science

and education, salary and financial decisions. First introduced in 1986 at Dongfeng and two other

auto producers, the system was quickly expanded to other groups, reaching 13 by 1989 (Table 3.4).

By the end of 1991 all of the trial groups were using the single track system. Of all the policies

directed at the trial groups this one appears to have spread very quickly and at the time was also

highly influential. Symbolically this policy elevated the core enterprise to the same level as the

planning authorities. Instead of receiving planning orders, the groups were able to make requests

directly to the state planning department and other necessary organs, informing them directly of

their plans and requirements. By 1991 the right to participate in relevant meetings with the Planning

Commission and other related departments was granted. The Planning Commissions role evolved to

providing macroeconomic information to the groups to help them better adjust in unpredictable

market conditions. The policy also raised the status of managing directors to vice-ministerial level,

though significantly their salaries were not raised in line with their new political status. The elevation

of the status of the business leaders reflected the growing importance attached to the trial groups in

political circles as well as the evolving and emerging ties between business and state leaders.

Although preferential planning was basically phased out as the plans importance diminished, it had

played an important role in stimulating the early development of the enterprise groups. As early as

1986 it recognized the need to clear away the restraints of the planning system and represented the

first coherent measure aimed at promoting business groups by empowering enterprises with the

most basic of production decisions. It was also the first step in the movement towards a more co-

ordinated business group strategy.

Internal finance companies

In July 1987 the first internal finance company was established, again at Dongfeng. This

corresponded to a time when relations between close members of the groups, concerning both

production and management, were growing ever closer. Exchanges of products and services had

increased quickly. At Dongfeng, for example, by 1987 a third of the groups total sales were made

between member enterprises (Chen, 1998). This in turn helped break down not only the regional

and departmental ownership structures between close members of the group, it also led to the

question of how better internal channels for distributing funds could be developed. A logical step

was to establish an organ that could productively harness funds, moving them from enterprises

making excess profits to those short of capital. The policy caught on and by 1994 there were 33 such

finance companies (Table 3.4). Recent empirical work, among the few studies in Western academia

on Chinese business groups, has found strong evidence to show that finance companies have

improved the financial and productivity performance among some of Chinas largest business groups

(Keister, 1998). The example of the finance company, therefore, stands out as an innovative

measure which, via the development of internal markets for credit, helped stimulate the

development of the groups.

The finance companies were restricted to activity within their groups. They tended also to be

established using group personnel. As a result this gave the finance companies unique insights into

their groups capabilities and longer term development strategies but sometimes financial expertise

was lacking. The problem with the traditional banking system was that it was not capable of

undertaking loans of sufficient size nor could it allocate them across the various provincial and

departmental boundaries that the business groups often spanned. Finance companies therefore

provided indispensable services. Among these were the provision of timely short-term credits to tide

over member enterprises in emergency situations and innovative measures, such as the introduction

of hire-purchase schemes. The banking system did not offer the kind of flexibility, dedication or

innovation needed to promote the interests of the trial groups. Among the problems with the

finance companies, however, has been their uneven distribution and lack of standardization. By July

1995 the Bank of China had approved the creation of a total of 53 finance companies, of which 35

belonged to the trial business groups. The 53 finance companies had total assets of 6.6 billion yuan

which at this time was equivalent to about one per cent of the entire financial sectors assets (Chen,

1998: 21). By 1997 this had increased to 1.6 per cent, and a further 16 finance companies had been

created, increasing the number to 69. However, within the trial groups some finance companies

remained very small with less than 100 million yuan in assets while others exceeded 7-8 times this

amount. The size disparities of the finance companies was in practice greatly dependent upon the

actual size of the group. Another problem with the finance companies in some cases has been that

the groups have been unaware of the potential roles such finance companies could play. As a result

they have not had a great impact on the groups. Nonetheless, the development of internal finance

companies has been an innovative and beneficial measure overall, with very strong evidence to

suggest that they have improved the financial and productivity performance of the groups.

Empowering business groups with the rights to manage state capital

This policy was introduced more slowly, but by 1997 renewed commitment was shown in efforts to

reform the rights to manage state property, a key element in clarifying the ownership relations

between the large numbers of group members. Again, Dongfeng was the first group to introduce this

policy under the guidance of the newly established State Capital Management Office in 1990. Later

in 1990, a small trial among three groups was run, including Dongfeng, Heavy Vehicle Group and

Dongfang Group. By 1992 official policy expanded the number undergoing the trial to 7 groups. From

February 1993 onwards more of the trial groups were given these rights. Provincial and city level

governments also started to introduce the policy, quickly widening its impact.

In the five years from 1982 to 1987 Dongfeng had grown from a group of just eight enterprises

spanning eight provinces to 118 enterprises spanning 21 provinces. However, as a leading group

representative commented, this amounted in reality to the linking of industrial departments, not

enterprises (Chen, 1992: 64). It became very difficult for Dongfeng to control group members, which,

though nominally linked to Dongfeng, were still in large part under local government control. In

extreme cases, for example, local authorities simply repossessed enterprises that Dongfeng had

turned back into profit. Closely related to this problem was the policy of the three no changes (san

bu bian) which during the 1980s stated that departmental relations, financial relations and

ownership rights within enterprises should not change. Under these conditions the expansion of

groups became seriously threatened. To combat this in September 1992 the State Capital

Management Office published On how to implement the empowerment of trial business groups

with state capital management rights clarifying issues related to the new policy. This specified that it

gave the rights to run the close members of the group to the core enterprise . . . . Establishing

between the core enterprise and its close members ownership ties, concentrating the groups power,

making the close members of the group become the cores wholly invested son companies or stock

controlled companies and giving play to the overall advantages of the group (emphasis added)

(SCMB, ZGZN, 1993:334). This measure, therefore, was designed to give the mother company

ownership and hence management control over the close members of the group. The mother

company came to supersede the previous regional and provincial controllers in place under the

policy of three no changes. By passing the rights to manage the close members of the group on to

the core of the group the policy of six unifications put forward in 1991, attempting to promote

cohesion, was logically extended. It delineated the responsibility for the management of state

capital, placing a firm responsibility with the groups core. This policy therefore stood out as another

strong endorsement of the positive function of the enterprise group.

Technology centres

Introduced in the 1997 directive, this has involved the annexation of existing scientific research

institutions to the business groups as well as the creation of new centres. By 1997 within the 120

business groups 71 state level research institutes had been created or annexed. Measures had also

been taken to force all large and medium enterprises to create their own research institutions or

face disciplinary measures, such as losing bank loans and also preferential access to material

supplies (CDBW, 3 April 1999). The central government has been busy in promoting ties between

research institutions and state enterprises, keenly aware that if Chinese enterprises are to be

successful, especially in the longer term, they must develop research capabilities. By the end of 1998

there were 203 state level and 500 provincial and city level R&D centres and 120,000 reported co-

operative efforts between universities, research institutions and state enterprises. Of the 203 state

level institutes 100 were affiliated to the national team players and 512 preferred enterprises

(CDBW, 3 April 1999). This reflected the wish of the State Council to push the groups from

technology-acquiring late-industrializing enterprises to modern corporations capable of innovating

themselves. Under the centrally planned system research was carried out in institutes well removed

from the activities of the plant, and much of the scientific progress was based upon imports from the

Soviet Union. It is unsurprising, therefore, that many enterprises still lack adequate research

capabilities. Even in 1997 about 80 per cent of all research was undertaken by the state research

bodies and 20 per cent by enterprises. In the US enterprises were responsible for half national R&D

expenditure and in Japan and Germany over 60 per cent (Li, 1999: 141). It is estimated that the top

500 global companies investment in R&D is about five to ten per cent of their total sales whereas in

China LMEs have invested no more than 1.5 per cent of sales in technical innovation since 1990

(CDBW, 17 January 2000). Given the great disparities in the average sales of Chinas largest

enterprises and her global competitors, already noted to be less than 2 per cent of the global

Fortune 500 enterprises for Chinas top 500 enterprises, it is evident that annual research

expenditures of global corporations vastly exceed those of Chinas largest groups.

By the eve of the reforms not only was China still quite technologically backward, there were also

relatively few resources contributed to research and development within enterprises. The

incorporation of research institutions into the trial groups represents another strategic step in

pushing forward the development of modern corporations in China and reflects the long-term vision

and hope of creating

If a country has several large companies or groups it will be assured of maintaining a certain

market share and a position in the international economic order. America, for example,

relies on General Motors, Boeing, Du Pont and a batch of other multinational companies.

Japan relies on six large business groups and Korea relies on 10 large commercial groupings.

In the same way now and in the next century our nations position in the international

economic order will be to a large extent determined by the position of our nations large

businesses and groups

Vice-premier Wu Bangguo, reported in the Jingji Ribao, in early 1997

By all accounts China has made outstanding economic progress in the past two decades. If

Chinas provinces were each considered individual nations, the twenty fastest growing nations

in the world from1978-95 would all be Chinese (World Bank, 1997: 2). It is sometimes argued

that Chinas rapid industrial development, the motor behind growth in this period, has been

primarily as a result of the speedy proliferation of small enterprises. The powerful imagery of

the healthy young shoots of small private enterprises pushing their way upwards in response to

sprinklings of market reform is an image that many observers hold dear. This interpretation

considers Chinas small enterprises the foundation for recent growth (World Bank, 1997: 21).

More recently, however, this view has been challenged by those who point out that although

small enterprises have played a very important role in Chinas recent industrial development,

the large-scale sector, predominantly state-owned, has also been critical (Lo, 1997; Lo, 1999;

Nolan, 1996; Nolan and Wang, 1998). Among other things they show that the number of large

and medium enterprises (LMEs) and their share of industrial output has increased significantly

during the reforms. Furthermore, LMEs are found predominantly in key upstream pillar

industries, often supplying smaller scale enterprises with basic producer goods, or in industries

with significant linkages. As well as this, despite being parched by years of planning, empirical

evidence now also suggests LME productivity and financial performance has bettered that of the

small-scale sector (Lo, 1999). In short, there is a growing weight of evidence suggesting the role

of the large-scale state sector has been of far greater importance in Chinas reform than has

previously been recognized.

Yet not unlike Japan in the 1950s and 1960s, and South Korea in the 1970s and 1980s, policy

makers and business leaders in China have made great efforts to nurture the saplings of big

business, particularly large enterprise groups.

One of the slogans state enterprise reform has now adopted is grasp the large, let go of the

small. The latter element, letting go of the small, is itself an important and interesting subject.

By the end of 1996 up to 70 per cent of small state-owned enterprises (SOEs) had already been

privatized in pioneering provinces and about a half in many other provinces. This was referred

to as a quiet revolution from below (Cao, Qian, and Weingast, 1999: 105). Equally

revolutionary measures, however, have also been undertaken in the large-scale sector. Of in

which successively 55 and 63 enterprise groups were selected to undergo influential trial

reforms.

8

Among the reform measures introduced were the development of internal group finance

companies, the systematic introduction of stock market listings, the promotion of preferential

planning within the groups giving them greater autonomy in basic decision making, granting of

import and export rights, the empowerment of the groups core with special rights to incorporate

state assets into the group and the creation of research and technology centres. Extensive financial

support from the banking sector and shelter from international competition by a wall of protective

tariffs, not mentioned in these directives, have also been provided. By the end of 1996 the 120

groups had swelled: alone they were accountable for more than 50 per cent of profits and

approximately 25 per cent of tax, total assets and total sales of state-owned industrial enterprises

in the independent accounting sector (SCDRC, ZJN, 1997: 677). Thousands of member

enterprises had been incorporated within the business groups of the national team players, as well

as many thousands more in preferred province level teams of business groups. Many of Chinas

LMEs, the large-scale sector, are now incorporated in the 2,302 enterprise groups registered at the

national or provincial level (Yin, Yuan, and Zang, 1999: 132).

9

In 1997 these groups accounted

for just 1.27 per cent of the total number of independent accounting enterprises but 51.1 per cent

of all assets and 45.5 per cent of all sales (Yin, Yuan, and Zang, 1999). An approximate

calculation suggests that these groups produced over 10 per cent of Chinas GDP (SSB, ZTN,

1998: 56; 431; 444).

10

The significance of policies instituted in the national team lies not only in

the impact on the 120 team players but also, perhaps even more importantly, the great influence

they have had and continue to exert as role models on the development of provincial and lower

level enterprise groups. Most provincial as well as hundreds more city and lower level

governments are nurturing their own teams of preferred enterprise groups.

11

As a result it is

probable that the scale and reach of central and local government industrial policy, if not its

effectiveness, far exceeds that which nations such as South Korea or Japan exercised during their

most impressive growth periods.

To a great extent the development of the national team of business groups has adopted the

traditional Chinese method of reform, using incremental steps, the groping for stones approach

as opposed to shock therapy. However, unlike many of the previous incremental reform

measures, those related to the trial business groups have over time developed explicitly stated

objectives as well as implicitly accepted time horizons. With WTO entry approaching, it is

considered imperative to develop a number of large enterprise groups to make up the backbone

of the national economy and the countrys main force to participate in international

competition.

12

Although by the mid 1990s most accounts agreed that China had already

succeeded in growing out of the plan there was still a great gulf between Chinese and foreign

multinationals. By 1999 there were still only 6 Chinese enterprises in the Global Fortune 500

listings, of which one was from Hong Kong, one a bank and two trade companies (Fortune, 2

August 1999).

13

Tariff barriers remained high, sheltering a number of strategic industries.

President Jiang Zemin at the 15

th

Party Conference in late 1997 summarized how efforts were to

be made to distil the state sector into key pillar or life blood industries of the national

economy using strategic adjustments to create highly competitive large enterprise groups:

particular relevance to this debate are two policy directives, officially issued in December 1991

and April 1997

Even as early as 1987 policy makers were issuing directives claiming the development of

business groups is of profound long-term importance to the development of production

capabilities and deepening the reform of the economic system (CRES, ZJTGN, 1988: IX-17). The

goal of grasping a batch of large enterprise groups, using capital ties to link and promote

enterprise restructuring, creating economies of scale and thoroughly giving play to their

backbone role more recently has also been included as part of long-term development plans up

to the year 2010 (CRES, ZJTGN, 1997: 243). This sentiment, even in the wake of the Asian

financial crisis, appears to have remained unchanged.

There is a strong consensus in China that large groups are vitally needed if it is to attain a

cherished goal of becoming a leading nation in the international economic order.

Insider lending appears to substitute for a formal financial system and to give firms access to

otherwise scarce capital where markets are inade- quate a t allocating funds (Goto 1982; Lamoreaux

1986). Informal financing arrangements allow funds to be allocated to their highest return uses

within a particular group, provides opportunities for diversification, and allows firms to engage in

otherwise unaffordable activities. Insider lending can mitigate certain informational asymmetries

and reduce transaction costs, allowing firms to gain control over their environments. During de-

velopment, for example, if banks exist, they are likely to be skeptical about unfamiliar potential

borrowers. Jnformal finance arrangements, that are often based on trust among well-acquainted

parties, reduce such risks by reducing the amount of information unknown to each party and the

costs associated with investigating potential borrowers (Williamson 1981). These arrangements

might also provide a vehicle for co-opting resources and thus further reducing environmental

uncertainties (Pfeffer and Salan- cik 1978). In China in the late 1980s, financial markets were unable

to distribute funds efficiently, which left many firms without necessary capital. Firms that were

members of some business groups had access to additional financing through the group's finance

company (caiwu gongsi), a specialized firm that collected and redistributed funds within the group

and also obtained funds through state banks on behalf of member firms (Shi 1995). Reformers

originally experimented with finance companies in the central industries and later in most other

industries (Li 1995). Initially the activities of the finance companies were not monitored, but as their

activity expanded regulations were implemented to control lending practices. The finance company

enabled the member firms to engage in research and development, to better manage investments

both within the group (i.e., investments in other firms that are members of the same group) and

out- side the group, and, if necessary, to meet short term operating expenses (for a description of

the emergence and functioning of finance companies in Chinese business groups see [Keister 1998).

The informational and market-substitute advantages of the group- specific bank suggest that firms in

Chinese business groups with finance companies should be advantaged over firms in groups that do

not have finance companies, and the more extensive the operations of the finance company, the

greater the advantages of this specialized firm.

Interlocking directorates are not new to China; they existed in government ministries before reform

when a single state representative was assigned to the boards of more than one firm (Schurmann

1965; Xie 1996).8 In the business groups, interlocks occur when member firms acquire shares in each

other and place representatives on each others' boards. The interlocks have the same functional

form as interlocks in other contexts (i.e., an individual occupies a seat on more than one board of

directors); however, unlike in the United States, where interlocks are both a source of information

(Davis 1992; Haunschild 1993; Mizruchi 1992) and a form of co-optation or monitoring (Aldrich 1979;

Dooley 1969; Mizruchi and Stearns 1988), interlocks in China primarily function as an information

source for the interlocked firms (Li 1995; SASBG 1995; Xie 1996).' The interlocks allow information

about technological advances, market oppor- tunities, innovative strategies, and so on, to pass

among firms in the group. Interlocks are not the only source on information available to firms, but

they are a central and predominant source. Because interlocks in China are not a form of co-optation,

they were viewed differently by Chinese managers during the 1980s than they are generally viewed

by Western managers. Chinese managers generally saw them as positive, as they tended to see most

forms of social connection among firms in the groups. (Keister, 1998).

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Security Operating Procedures and StandardsDokument5 SeitenSecurity Operating Procedures and StandardsQuy Tranxuan100% (2)

- AS Unit 1 Revision Note Physics IAL EdexcelDokument9 SeitenAS Unit 1 Revision Note Physics IAL EdexcelMahbub Khan100% (1)

- Business Analytics Case Study - NetflixDokument2 SeitenBusiness Analytics Case Study - NetflixPurav PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crib Sheet BridgeDokument2 SeitenCrib Sheet Bridge92_883755689100% (1)

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDokument3 SeitenNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentVince Vince100% (1)

- Clusters and Economic Policy White PaperDokument10 SeitenClusters and Economic Policy White PaperShahzod QuchkorovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of State Owned Enterprises ChinaDokument21 SeitenRole of State Owned Enterprises ChinaFelipe QuintasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial and Operating Performance of Privatized Firms A Case Study of PakistanDokument27 SeitenFinancial and Operating Performance of Privatized Firms A Case Study of PakistanSuhrab Khan JamaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Industrial Policy Implementation: Empirical Evidence From China's Shipbuilding IndustryDokument3 SeitenIndustrial Policy Implementation: Empirical Evidence From China's Shipbuilding IndustryCato InstituteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Financenext Term and State Enterprise Reform in Previous Termchinanext TermDokument31 SeitenCorporate Financenext Term and State Enterprise Reform in Previous Termchinanext TermIchbinleoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4Dokument29 SeitenChapter 4Nada ElDeebNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate ResturctureDokument26 SeitenCorporate ResturcturehetugotuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macroeconomic Reforms and A Labour Policy Framework For India Jayati GhoshDokument53 SeitenMacroeconomic Reforms and A Labour Policy Framework For India Jayati GhoshVipul KhannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Multinational Corporation and Global Governance Modelling Public Policy NetworksDokument14 SeitenThe Multinational Corporation and Global Governance Modelling Public Policy NetworksNeil MorrisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Management in The Non-Profit OrganisationsDokument17 SeitenStrategic Management in The Non-Profit OrganisationsMuhammad Imran SharifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Privatization in India Issues and EvidenceDokument18 SeitenPrivatization in India Issues and EvidencePradeep Kumar RevuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1043951X17301761 Main PDFDokument3 Seiten1 s2.0 S1043951X17301761 Main PDFabadittadesseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Privatisation and The Role of Public and Private Institutions in Restructuring ProgrammesDokument24 SeitenPrivatisation and The Role of Public and Private Institutions in Restructuring Programmesasdf789456123100% (1)

- HSG Report - 2011 China Legal and Regulatory AnalysisDokument77 SeitenHSG Report - 2011 China Legal and Regulatory Analysisapi-536548929Noch keine Bewertungen

- White Et Al-2008-Management and Organization ReviewDokument32 SeitenWhite Et Al-2008-Management and Organization ReviewArslan QayyumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Industrial Policy DebateDokument8 SeitenIndustrial Policy Debateandinua9525Noch keine Bewertungen

- 20CH10064 - Sneha MajumderDokument16 Seiten20CH10064 - Sneha MajumderRashi GoyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Will Bartlett and Vladimir Bukvič 2001Dokument20 SeitenWill Bartlett and Vladimir Bukvič 2001ImranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Does Privatization Lead To Benign OutcomesDokument18 SeitenDoes Privatization Lead To Benign OutcomesNikit ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ross Schneider 2009 A Comparative Political Economy of Diversified Business GroupsDokument31 SeitenRoss Schneider 2009 A Comparative Political Economy of Diversified Business GroupsCarlos PalaciosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurship EssayDokument4 SeitenEntrepreneurship Essay92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Synthesis Paper About COMPREHENSIVE POLICIES TOWARDS ENTREPRENEURIAL DYNAMISM AN UPDATE MODEL FOR THE ASIA PACIFIC REGION AND THE LESS AND LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIESDokument4 SeitenSynthesis Paper About COMPREHENSIVE POLICIES TOWARDS ENTREPRENEURIAL DYNAMISM AN UPDATE MODEL FOR THE ASIA PACIFIC REGION AND THE LESS AND LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIESRufa Mae RadinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research IncompleteDokument42 SeitenResearch Incompletehikagayahachiman9Noch keine Bewertungen

- Detailed Report On Privatisation and DisinvestmentDokument37 SeitenDetailed Report On Privatisation and DisinvestmentSunaina Jain50% (2)

- Disinvestment and PrivatisationDokument40 SeitenDisinvestment and Privatisationpiyush909Noch keine Bewertungen

- Disinvestment and PrivatisationDokument30 SeitenDisinvestment and PrivatisationSantosh MashalNoch keine Bewertungen

- How State-owned Enterprises Drag on Economic Growth: Theory and Evidence from ChinaVon EverandHow State-owned Enterprises Drag on Economic Growth: Theory and Evidence from ChinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final ThesisDokument66 SeitenFinal ThesisHiromi Ann ZoletaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Are The Best Ways of Supporting Entrepreneurship For Economic Development?Dokument13 SeitenWhat Are The Best Ways of Supporting Entrepreneurship For Economic Development?Sdimt FaridabadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept of Corporate Governance in Development Country Vs Developing CountyDokument8 SeitenConcept of Corporate Governance in Development Country Vs Developing CountysakibhasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chinese Strategic State-Owned Enterprises and Ownership ControlDokument14 SeitenChinese Strategic State-Owned Enterprises and Ownership ControlChantich CharmtongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chaebols Financial Liberalization and EcDokument45 SeitenChaebols Financial Liberalization and EcMarketing ScienceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article Review On PorterDokument12 SeitenArticle Review On PorterGizachew AlazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad: Morris@iimahd - Ernet.in Rakesh@iimahd - Ernet.inDokument42 SeitenIndian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad: Morris@iimahd - Ernet.in Rakesh@iimahd - Ernet.inPushpa LathaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4998 B Introduction SBRDokument2 Seiten4998 B Introduction SBRSantiago CunialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Causes of PrivatisationDokument9 SeitenCauses of PrivatisationNipunNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Evolution and Restructuring of Diversified Business Groups in Emerging Markets: The Lessons From Chaebols in KoreaDokument24 SeitenThe Evolution and Restructuring of Diversified Business Groups in Emerging Markets: The Lessons From Chaebols in KoreafalmendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Privatisation in Developing Countries (Performance and Ownership Effects)Dokument34 SeitenPrivatisation in Developing Countries (Performance and Ownership Effects)Hanan RadityaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MRK Per... 1-1Dokument41 SeitenMRK Per... 1-1Ajai KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Entrepreneurial Orientations in State-Owned Enterprises in MalaysiaDokument11 SeitenCorporate Entrepreneurial Orientations in State-Owned Enterprises in MalaysiaDr. Harry Entebang100% (2)

- Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Financing A Review of LiteratureDokument5 SeitenSmall and Medium-Sized Enterprises Financing A Review of LiteratureaflruomdeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.transferable Lessons Re Examining The Institutional Prerequisites of East Asian Economic Policies PDFDokument22 Seiten1.transferable Lessons Re Examining The Institutional Prerequisites of East Asian Economic Policies PDFbigsushant7132Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Public Enterprise in The 80S: Problems and IssuesDokument8 SeitenPhilippine Public Enterprise in The 80S: Problems and Issuesdexie de guzmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public, Private and Joint SectorsDokument10 SeitenPublic, Private and Joint SectorsAMITKUMARJADONNoch keine Bewertungen

- ALAS - PHD 201 AR #3Dokument4 SeitenALAS - PHD 201 AR #3Queenie Marie AlasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qi Kotz 2019 The Impact of State Owned Enterprises On China S Economic GrowthDokument19 SeitenQi Kotz 2019 The Impact of State Owned Enterprises On China S Economic GrowthsergiolefNoch keine Bewertungen

- Katoch Bahri State EnterprisesDokument30 SeitenKatoch Bahri State Enterprisesrahul sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Skills ManagementDokument61 SeitenSkills ManagementSudeep Chinnabathini100% (1)

- Impact of Privatization On Organization 2Dokument8 SeitenImpact of Privatization On Organization 2Yasmeen AtharNoch keine Bewertungen

- MRK pwr1-1 - 220609 - 154133Dokument167 SeitenMRK pwr1-1 - 220609 - 154133sadhvi sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Privatisation in IndiaDokument5 SeitenPrivatisation in IndiaGaurav KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment On New Economic EnviornmentDokument13 SeitenAssignment On New Economic EnviornmentPrakash KumawatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Industrial Agglomeration - PIDSDokument63 SeitenIndustrial Agglomeration - PIDSJack DanielsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disinvestment An OverviewDokument8 SeitenDisinvestment An OverviewRavindra GoyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic InvestmentDokument15 SeitenStrategic InvestmentMananNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 1 Why Should Business Students Understand Government?Dokument3 SeitenWeek 1 Why Should Business Students Understand Government?vamuya sheriffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trade and Competitiveness Global PracticeVon EverandTrade and Competitiveness Global PracticeBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- The What, The Why, The How: Mergers and AcquisitionsVon EverandThe What, The Why, The How: Mergers and AcquisitionsBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- Reforming Asian Labor Systems: Economic Tensions and Worker DissentVon EverandReforming Asian Labor Systems: Economic Tensions and Worker DissentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Somaliland: Private Sector-Led Growth and Transformation StrategyVon EverandSomaliland: Private Sector-Led Growth and Transformation StrategyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internal Consistency, Reliability, and Temporal Stability of The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire Short-Form - Test-Retest Data Over Two WeeksDokument9 SeitenInternal Consistency, Reliability, and Temporal Stability of The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire Short-Form - Test-Retest Data Over Two Weeks92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Seminar 7 - Innovation and Technological Change: Industrial OrganisationDokument7 SeitenSeminar 7 - Innovation and Technological Change: Industrial Organisation92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Resonance - A Destructive Power: DiscoveryDokument5 SeitenResonance - A Destructive Power: Discovery92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurship EssayDokument4 SeitenEntrepreneurship Essay92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Tax Evasion FrameworkDokument2 SeitenThe Tax Evasion Framework92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hurricane EssayDokument3 SeitenHurricane Essay92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Industrial Organisation: Seminar 6 - Market Structure and PerformanceDokument1 SeiteIndustrial Organisation: Seminar 6 - Market Structure and Performance92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Air Pollution in Mexico CityDokument1 SeiteAir Pollution in Mexico City92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1) Seller ConcentrationDokument5 Seiten1) Seller Concentration92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Keiretsu 1Dokument6 SeitenKeiretsu 192_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Harvard Referencing GuideDokument4 SeitenHarvard Referencing Guide92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Collusion EssayDokument6 SeitenCollusion Essay92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Auctions EssayDokument6 SeitenAuctions Essay92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Poole (1970) Exam AnswerDokument7 SeitenPoole (1970) Exam Answer92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Central Planning EssayDokument5 SeitenCentral Planning Essay92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Exit and Survival NotesDokument11 SeitenExit and Survival Notes92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rogoff (1985) ConservativeDokument5 SeitenRogoff (1985) Conservative92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cartel FormationDokument4 SeitenCartel Formation92_883755689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mindfulness of Breathing and The Four Elements MeditationDokument98 SeitenMindfulness of Breathing and The Four Elements Meditationulrich_ehrenbergerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Download Test Bank For Ethics Theory and Contemporary Issues 9th Edition Mackinnon PDF Full ChapterDokument36 SeitenFull Download Test Bank For Ethics Theory and Contemporary Issues 9th Edition Mackinnon PDF Full Chapterpapismlepal.b8x1100% (16)

- StratificationDokument91 SeitenStratificationAshish NairNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 - List of Equipment, Tools & MaterialsDokument3 Seiten2019 - List of Equipment, Tools & Materialsreynald manzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSC-MEPC.6-Circ.21 As at 31 October 2023Dokument61 SeitenMSC-MEPC.6-Circ.21 As at 31 October 2023nedaldahha27Noch keine Bewertungen

- Appraisal: Gilmore and Williams: Human Resource ManagementDokument18 SeitenAppraisal: Gilmore and Williams: Human Resource ManagementShilpa GoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leaders Eat Last Key PointsDokument8 SeitenLeaders Eat Last Key Pointsfidoja100% (2)

- Using Open-Ended Tools in Facilitating Mathematics and Science LearningDokument59 SeitenUsing Open-Ended Tools in Facilitating Mathematics and Science LearningDomina Jayne PagapulaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Strategic Cost Management and Management AccountingDokument3 SeitenIntroduction To Strategic Cost Management and Management AccountingnovyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bibliografia Antenas y RadioDokument3 SeitenBibliografia Antenas y RadioJorge HerreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wp406 DSP Design ProductivityDokument14 SeitenWp406 DSP Design ProductivityStar LiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Untitled PresentationDokument23 SeitenUntitled Presentationapi-543394268Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kanne Gerber Et Al Vineland 2010Dokument12 SeitenKanne Gerber Et Al Vineland 2010Gh8jfyjnNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECAT STD 2 Sample Question PaperDokument7 SeitenECAT STD 2 Sample Question PaperVinay Jindal0% (1)

- Chen, Y.-K., Shen, C.-H., Kao, L., & Yeh, C. Y. (2018) .Dokument40 SeitenChen, Y.-K., Shen, C.-H., Kao, L., & Yeh, C. Y. (2018) .Vita NataliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metsec Steel Framing SystemDokument46 SeitenMetsec Steel Framing Systemleonil7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Designation of Mam EdenDokument2 SeitenDesignation of Mam EdenNHASSER PASANDALANNoch keine Bewertungen

- West Visayas State University (CHECKLIST FOR FS)Dokument3 SeitenWest Visayas State University (CHECKLIST FOR FS)Nichole Manalo - PoticarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of Design 2Dokument98 SeitenTheory of Design 2Thirumeni MadavanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bus Terminal Building AreasDokument3 SeitenBus Terminal Building AreasRohit Kashyap100% (1)

- Atf Fire Research Laboratory - Technical Bulletin 02 0Dokument7 SeitenAtf Fire Research Laboratory - Technical Bulletin 02 0Mauricio Gallego GilNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Highways Authority of IndiaDokument3 SeitenNational Highways Authority of IndiaRohitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment # (02) : Abasyn University Peshawar Department of Computer ScienceDokument4 SeitenAssignment # (02) : Abasyn University Peshawar Department of Computer ScienceAndroid 360Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pineapple Working PaperDokument57 SeitenPineapple Working PaperAnonymous EAineTiz100% (7)

- Medical and Health Care DocumentDokument6 SeitenMedical and Health Care Document786waqar786Noch keine Bewertungen

- SAmple Format (Police Report)Dokument3 SeitenSAmple Format (Police Report)Johnpatrick DejesusNoch keine Bewertungen