Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Business Law Notes

Hochgeladen von

Tabish Ahmed0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

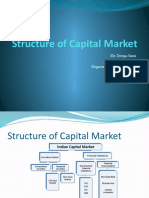

228 Ansichten27 SeitenThis document summarizes key aspects of contract law in India as outlined in the Indian Contract Act of 1872. It discusses the definition and types of contracts, including valid, voidable, void, illegal, and unenforceable contracts. It also describes the essential elements required for a valid contract, including offer and acceptance. Specifically, it defines what constitutes a legal offer and acceptance and the rules around offer, acceptance, and formation of a contract.

Originalbeschreibung:

notes

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThis document summarizes key aspects of contract law in India as outlined in the Indian Contract Act of 1872. It discusses the definition and types of contracts, including valid, voidable, void, illegal, and unenforceable contracts. It also describes the essential elements required for a valid contract, including offer and acceptance. Specifically, it defines what constitutes a legal offer and acceptance and the rules around offer, acceptance, and formation of a contract.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

228 Ansichten27 SeitenBusiness Law Notes

Hochgeladen von

Tabish AhmedThis document summarizes key aspects of contract law in India as outlined in the Indian Contract Act of 1872. It discusses the definition and types of contracts, including valid, voidable, void, illegal, and unenforceable contracts. It also describes the essential elements required for a valid contract, including offer and acceptance. Specifically, it defines what constitutes a legal offer and acceptance and the rules around offer, acceptance, and formation of a contract.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 27

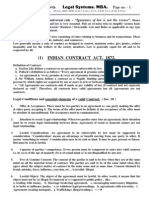

INDIAN CONTRACT ACT, 1872

MEANING AND TYPES OF CONTRACTS

The law relating to the contracts is contained in the Indian Contract Act,

1872. It is that branch of law which lays down the essentials of a valid contract, the

different modes of discharging the contract and the remedies available to the aggrieved

party in the case of breach of contract. It is the most important branch of business law. It

is, of particular importance to people engaged in trade, commerce and industry as bulk

of their business transactions are based on contracts.

A contract is an agreement made between two or more parties which the law will

enforce. Sec. 2 (h) of the Indian Contract Act defines it as An agreement enforceable

by law. Sec. 10 lays down that All agreements are contracts if they are made by the

free consent of parties competent to contract, for a lawful consideration and with a

lawful object and are not hereby expressly declared to be void.

CLASSIFICATION OF CONTRACTS

Contracts may be classified according to their validity, formation or performance.

I CLASSIFICATION ACCORDING TO VALIDITY

A contract is based on an agreement. An agreement becomes a contract when all the

essential elements referred to above are present. In such a case, the contract is a valid

contract. If one or more of these elements are missing, the contract is either voidable,

void, illegal or unenforceable.

Voidable Contract

Voidable contract is an agreement that is binding and enforceable, but because of the

lack of one or more of the essentials of a valid contract, it may be repudiated by the

aggrieved party at his option.

Example: A promises to sell his house to B for Rs.2 lakhs. A obtained Bs consent by

exercising fraud on the latter. The contract is voidable at the option of B.

Void Contract

A contract which is not enforceable by law is a void contract. It confers no right on any

person and creates no obligations.

Example: A promises for no consideration, to give to B Rs.1000. This contract is void.

Illegal Contracts

An illegal contract is one which are opposed to statutory law or public morals. It is

criminal in nature. The effect of an illegal contract is that, it not only makes the

transaction between the immediate parties void, but also render the collateral

transactions void.

Example: A borrows Rs.1000 from B for manufacturing bombs. As manufacturing

bombs is illegal, the contract is void.

Unenforceable Contract

An unenforceable contract is one which cannot be enforced in a Court of law because of

some technical defect.

Example:

(i) A debt barred by limitation is unenforceable.

(ii) A document for want of prescribed value of the stamp is unenforceable.

II CLASSIFICATION ACCORDING TO FORMATION

Contracts may be classified according to the mode of their formation as follows:

Express Contract

If the terms of a contract are expressly agreed upon, whether by words spoken or

written at the time of the formation of the contract, the contract is said to be an express

contract.

Implied Contract

An implied contract is one which is inferred from the acts or conduct of the parties or

course of dealings between them. It is not the result of any express promise or promises

by the parties but of their particular act.

Example: A, enters into a hotel and takes lunch. It is an implied contract that he has to

pay the cost of lunch after taking it.

III CLASSIFICATION ACCORDING TO PERFORMANCE

These may be classified as Executed contracts or Executory contracts,

Executed Contracts

An executed contract is one in which both the parties have performed their respective

obligations.

Example: A agrees to sell a book to B for Rs.200. When A delivers the book and B pays

the price, the contract is said to be executed.

Executory Contracts

An executory contract is one in which both the parties have yet to perform their

obligations. Thus in the above example, the contract is executory if A has not delivered

the book and B has not paid the price.

ESSENTIALS OF A VALID CONTRACT

A valid contract must have the following essentials:

1. Two parties: There must be two parties for a valid contract.

2. Offer and acceptance: There must be an offer and acceptance. One party making the

offer and the other party accepting it.

3. Consensus-ad-idem or Identity of Minds: The parties to the contract must have

agreed about the subject matter of the contract at the same time and in the same

sense.

Illustration: A has two houses, one at Karaikudi and another at Madurai.

He has offered to sell one to B. B accepts thinking to purchase the house at Karaikudi,

while A, when he offers, has in his mind to dispose of house at Madurai. There is no

Consensus-ad-idem.

4. Consideration: It means something in return. Every contract must be supported by

consideration.

Illustration: A offers to sell his watch for Rs.800 to B and B accepts the offer. Thus,

Rs.800 is the consideration for the watch and vice-versa. 5. Capacity: The parties to the

contract must be competent to contract. For example, a contract by a minor is void,

since he is not competent to contract.

6. Free Consent: The consent of the parties must be free from any flaw. It must not be

caused by a mistake or coercion or undue influence.

7. Lawful Consideration: The consideration to a contract must be lawful.

Illustration: A promises to pay Rs.500/- to B, in consideration of B murdering C. The

consideration is illegal.

8. Lawful object: The object of the contract must be lawful.

Illustration: A promises to pay Rs.500/- for letting Bs house for running a brothel. The

object is illegal. Hence, the contract is void.

Thus, the essence of a legal contract is that there shall be an agreement between two

persons, that one of them shall do something either for the benefit of the other or for his

own detriment and that these persons intend that the agreement shall be enforceable at

law.

OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE

OFFER

One of the early steps in the formation of contract lies in arriving at an agreement

between the contracting parties by means of offer and acceptance. One party makes a

definite proposal to the other, and that other accepts it in its entirety.

An offer is also called a proposal. Sec.2 (a) of the Indian Contract Act defines a

proposal as, When one person signifies to another his willingness to do or to abstain

from doing anything, with a view to obtaining the assent of that other to such act or

abstinence, he is said to make a proposal. The person making the proposal is called

the proposer, or offeror and the person to whom the proposal is made is called the

offeree.

LEGAL RULES RELATING TO OFFER

1. It must contain definite, unambiguous and certain and not loose and vague terms.

Montreal Gas Co Vs Vasey: It was held in this case, that a clause to favourably consider

the application for renewal, is ambiguous and not binding the company.

Taylor Vs Portington: The terms to put the house into thorough repairs and decorate

drawing rooms according to present style, were held uncertain.

2. It must intend to give rise to legal relationship. A social invitation, even if it is accepted

does not create legal relationship, because it is not so intended.

Balfour Vs Balfour: A husband promised to pay Rs.1000/- per month to his wife, staying

away from him. Held that the promise was never intended to be enforced in law.

3. It must be distinguished from a quotation or an invitation to offer.

MacPherson Vs. Appanna: P offered to buy Ds property for Rs.6000. D replied, Wont

accept less than Rs.10,000. P agreed to pay Rs.10,000. But D sold it to another

person. It was held that mere statement of price by D contained no implied contract to

sell it at that price.

4. An offer may be made to an individual or addressed to the world at large.

An offer is called a specific offer when it is made to a particular person.

Carlill Vs Carbolic Smoke Ball Co: The company has offered by advertisement, a

reward of 100 to anybody contracting influenza after using their smoke ball according

to their direction. Mrs. Carlill used it as directed but still had an attack of influenza.

Hence, she sued for the award of 100.

It was held that she was entitled to the award since an offer made at large, can ripen

itself into a contract with anybody who performs the terms of the offer.

5. Offer must be made with a view to obtaining the assent.

The offer to do or not to do something must be made with a view to obtaining the assent

of the other party addressed and not merely with a view to disclosing the intention of

making an offer.

6. An offer must be communicated to the offeree.

Lalman Shukla Vs Gowri Dutt: As nephew was missing. B, who was an employee of A,

volunteered his services to search for the boy. Meanwhile, A had announced a reward

to anybody who could trace the boy. B found the boy and brought him back to home

and sued for the reward. It was held that he was not entitled to the reward as he was

ignorant of the offer.

Section 4 lays down that the communication of an offer is complete only when it

reaches the offeree. So, an offer binds the offeror only when the offeree has the

knowledge of the offer.

ACCEPTANCE

Section 2 (b) of the Indian Contract Act defines acceptance as, When the person to

whom the proposal is made signifies his assent thereto, the proposal is said to be

accepted. A proposal, when accepted becomes a promise. An offer, when accepted,

becomes a contract. Acceptance may be express or implied. It is express when it is

communicated by words spoken or written or by doing some required act. It is implied

when it is to be gathered from the surrounding circumstances or the conduct of the

parties.

Essentials of Valid Acceptance

1. Acceptance must be absolute and unconditional and should correspond with the

terms of the offeror. Otherwise, it amount to counter offer which may be accepted or

rejected by the offeror.

For example, A offers to sell his car for Rs.l lakh. B asks for Rs. 70,000.

It is not an acceptance, but a counter offer only.

2. An offer can be accepted only by the persons to whom the offer is made.

Boulton Vs Jones: A sold his business to B. This sale is not known to As customers.

So, Jones, who is a usual customer of the vendor, places an order for goods with the

vendor A by name. B, the new owner, receives the order and supplies the goods

without disclosing the fact of sale of business to him. It was held that the price could not

be recovered as the contract was not entered into with him.

3. Acceptance must be communicated in usual and reasonable manner. It may be made

by express words, spoken or written or by conduct of the parties, i.e. by doing an act

which amounts to acceptance according to the terms of the offer or by the offeree

accepting the benefit offered by the offeror.

Any method can be prescribed for the communication of acceptance. It must be

according to the mode prescribed or usual and reasonable mode.

Silence can never be prescribed as a method of communication. Hence, mere mental

assent without expressing it and communicating it by means of word or an act, is not

sufficient.

Example: A wrote to B, I offer you my car for Rs.10,000. If I dont hear from you in

seven days, I shall assume that you accept. B did not reply at all. There is no contract.

Brogden Vs Metropolitan Railway Co: The Manager of a railway company simply wrote

on the proposal approved and kept it in a drawer.

By oversight, it was not communicated. It was held that the acceptance was not

communicated and hence there was no contract.

4. Acceptance must be made within a reasonable time. If any time limit is specified, the

acceptance must be given within that time. If no time limit is specified, it must be given

within a reasonable time.

Example: On June 8 M offered to take shares in R company. He received a letter of

acceptance on November 23. He refused to take the shares. Held, M was entitled to

refuse as his offer had lapsed as the reasonable period during which it could be

accepted had elapsed.

5. Acceptance should be made before the offer lapses or is revoked or is rejected.

6. Acceptance cannot precede an offer. If the acceptance precedes an offer, it is not a

valid acceptance and does not result in a contract.

Example: In a company, shares were allotted to a person who had not applied for them.

Subsequently when he applied for shares, he was unaware of the previous allotment.

The allotment of shares previous to the application is invalid.

7. Communication of acceptance may be waived by the offeror.

This rule is established in the case of Carlill Vs Carbolic Smoke Ball

Company where the advertisement never wanted the communication, apart from

fulfilling the conditions of offer.

Acceptance, once made, Concludes the Contract

The rule is that when once an offer is accepted, it concludes the contract.

So, an acceptance is irrevocable. When a lighted match is applied to gun powder it

produces something which cannot be recalled. Sir William Anson compares here the

gun powder to an offer and the lighted match to acceptance and says that either

the gun powder may be allowed to become damp or it may be removed before the

lighted match is applied. So also an offer may be allowed to lapse for lack of

acceptance or may be revoked before acceptance is given. But when once acceptance

is given, it ripens into contract, just as when a lighted match is applied to gun powder it

produces an explosion. Thus he emphasizes two things: (i) There cannot be an

acceptance after revocation of the offer and

(ii) When once there is an acceptance, there can be no revocation.

COMMUNICATION OF OFFER, ACCEPTANCE AND REVOCATION

An offer, its acceptance and their revocation to be complete must be communicated.

1. The communication of an offer is complete when it comes to the knowledge of the

person to whom it is made.

Example: A proposes, by a letter, to sell a house to B at a certain price.

The letter is posted on 10th July. It reaches B on 15th July. The communication of the

offer is complete when B receives the letter on 15

th

July.

2. The communication of acceptance is complete

as against the proposer when it is put into a course of transmission to him, so as to be

out of the power of the acceptor;

as against the acceptor when it comes to the knowledge of the proposer.

Example: B accepts As proposal, in the above case, by a letter sent

by post on 16th July. The letter reaches A on 18th instant. The communication of the

acceptance is complete, as against A, when the letter is posted, i.e. on 16th. As against

B, when the letter is received by A, i.e. on 18th.

3. The communication revocation is complete

as against the person who makes it, when it is put into a course of transmission to

the person to whom it is made, so as to be out of the power of the person who makes it;

as against the person to whom it is made, when it comes to his knowledge.

Time for revocation of Offer and Acceptance

An offer may be revoked at any time before the communication of its acceptance is

complete as against the offeror, but not afterwards. An acceptance may be revoked at

any time before the communication of the acceptance is complete as against the

acceptor, but not afterwards.

CONSIDERATION AND CAPACITY

Consideration is one of the essential elements of a contract. Consideration is known as quid pro

quo, i.e. something in return for something. When a party to an agreement promises to do

something, he must get something in return. This something is defined as consideration.

Section 2 (d) of the Indian Contract Act defines consideration thus: When at the desire of the

promisor, the promisee or any other person has done or abstained from doing, or does or

abstains from doing, or promises to do or abstain from doing something, such act or abstinence

or promise is called a consideration for the promise. legal rules as to consideration

1. Consideration at the Desire of the Promisor

Consideration must proceed at the request or desire of the promisor. Hence, acts done

voluntarily or at the request of third parties do not constitute a valid consideration.

Durga Prasad Vs Baldev: A built a market at the request of the Collector of the place. B

promised to pay A, commission on the articles sold in the market. It was held that Bs promise to

pay commission did not constitute a valid consideration because A did not build the market at

the request of B.

1. The Promisee or any other Person

Consideration may move from the promisee or any third party. Hence, a stranger to onsideration

can sue on the contract.

2. It may be an act, abstinence or forbearance or a return promise

i) An act, i.e. doing of something. In this sense consideration is in an affirmative form.

ii) An abstinence or forbearance, i.e. abstaining or refraining from doing something. In this

sense consideration is in a negative form.

Example: A promises B not to file a suit against him if he pays him Rs.10,000. The abstinence

of A is the consideration for Bs payment.

iii) A return promise.

Example: A agrees to sell his horse to B for Rs.30,000. Here Bs promise to pay the sum of

Rs.30,000 is the consideration for As promise to sell the horse, and As promise to sell the

horse is the consideration for Bs promise to pay the sum of Rs.30,000.

3. Consideration may be past, present or future

The words used in Sec.2(d) are: . has done or abstained from doing (past), or does or

abstains from doing (present), or promises to do or to abstain from doing (future) something

.. This means consideration may be past, present or future.

a) Consideration may be past: When consideration by a party for a present promise was given

in the past.

Example: A renders some service to B at latters desire. After a month B promises to

compensate A for the services rendered to him. It is past consideration.

b) Consideration may be present: When consideration is given simultaneously with promise, it is

said to be present consideration.

Example: A receives Rs.500 in return for which he delivers a watch to B. The money A receives

is the present consideration for which he delivers the watch.

c) Consideration may be future: When consideration from one party to the other is to pass

subsequently to the making of the contract, it is future consideration.

Example: A promises to deliver certain goods to B after a week and B promises to pay the price

after a fortnight. Consideration in this case is future.

4. Something in return for Something There must be something in return. This

something in return need not necessarily be equal in value to something given.

Consideration need not be adequate. But it must be real and lawful.

Example: A agrees to sell a cow worth Rs.1200 for Rs.10. He has given his consent freely. The

agreement is a contract though consideration is inadequate.

5. Consideration must be real and not illusory

Although consideration need not be adequate, it must be real, competent and of some value in

the eyes of the law.

Example: A promise to create treasure by magic or to join two straight lines together cannot be

regarded as valid consideration.

6. Consideration must be something which the promisor is not already bound to do

A promise to do what one is already bound to do, either by general law or under an existing

contract, is not a consideration.

7. Consideration should not be illegal, immoral or opposed to public policy

Example: A married woman was given money to enable her to obtain divorce from her husband

and then to marry the lender. Held, the agreement was immoral and the lender could not

recover the money.

Capacity to contract

The parties who enter into a contract must have the capacity to do so. Capacity means the

competence of the parties to understand the nature of the contract and the rights and liabilities

arising out of those contract.

According to Sec. 11, every person is competent to contract who

(a) is of the age of majority according to the law, to which he is subject,

(b) is of sound mind, and

(c) is not disqualified from contracting by any law to which he is subject.

Thus the following persons are incompetent to contract:

(i) Minors

(ii) Persons of unsound mind, and

(iii) Persons disqualified by any law to which they are subject incapacity to contract

Incapacity may arise out of (a) Status and (b) Mental deficiency.

(A) Incapacity Arising out of Status

Alien Enemies: An alien is a person who belongs to a foreign state. He may be an alien friend

or an alien enemy.

Contracts with an alien friend are valid. Contracts made with an alien enemy before the war may

either be suspended or discharged.

During the continuance of the war, an alien enemy can neither contract with an Indian subject

nor can he sue in an Indian Court.

Foreign Sovereigns, their diplomatic staff and accredited representatives of foreign States:

They have some special privileges and generally cannot be sued unless they of their own

submit to the jurisdiction of our law Courts. They can enter into contracts and enforce those

contracts in our Courts.

But an Indian citizen has to obtain a prior sanction of the Central Government in order to sue

them in our Courts.

Convict: A convict when undergoing imprisonment is incapable of entering into a contract.

Insolvent: The insolvent cannot enter into contract and bind his property as his property shall be

vested with the official receiver when he is adjudged as insolvent.

(B) Incapacity Arising from Mental Deficiency

A person is said to be mentally deficient when (a) he does not attain majority, e.g. a minor, or

(b) he is of unsound mind.

1. When he is a Minor

A minor is a person who has not completed 18 years of age. He attains majority on completion

of

18 years. A minor cannot enter into a valid contract.

2. When he is of Unsound Mind

Section 12 lays down that A person is said to be of sound mind for the purpose of making a

contract if, at the time when he makes it, he is capable of understanding it and of forming a

rational judgement as to its effect upon his interests. A person who is usually of unsound mind,

but occasionally of sound mind, may make a contract when he is of sound mind.

Illustration: A patient in a lunatic asylum, who is at intervals, of sound mind, may contract during

those intervals.

Law relating to contracts entered into by minors

According to Sec.3 of the Indian Majority Act, 1875, a minor is a person who has not completed

eighteen years of age. He attains majority on completion of 21 years when his property

ismanaged by court of wards or a guardian.

1) A contract by a minor is void and inoperative ab initio (from the beginning).

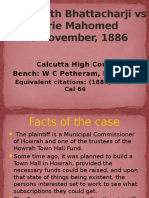

Mohoribibi Vs Dharmodas Ghosh: A minor had executed a mortgage for Rs.20,000. The money-

lender had paid Rs.8000 on the security of the mortgage. The minor sued for setting aside the

mortgage. It was held that a contract by a minor was void and that the amount advanced by the

lender could not be recovered under Sections 64 and 65 of the Indian Contract Act.

2) Minors agreement cannot be ratified by him on attaining the age of majority.

Arumugam Vs Duraisinga: A minor, having given a promissory note during his minority, has

executed another note on attaining majority in settlement of the first note. It was held that the

second note executed by the minor is void.

3) He can be a promisee or a beneficiary. Incapacity of a minor to enter into a contract does not

debar him from becoming a beneficiary. Such contracts may be enforced at his option, but not

at the option of the other party.

Example: M aged 17, agreed to purchase a second-hand scooter for Rs.5,000 from S. He paid

Rs.200 as advance and agreed to pay the balance the next day. S told him that he had changed

his mind and offered to return the advance. S cannot avoid the contract.

4) If the minor has received any benefit under a void agreement, he cannot be asked to

compensate or pay for it.

Example: M, a minor, obtains a loan by mortgaging his property. He is not liable to refund the

loan. Not only this, even his mortgaged property cannot be made liable to pay the debt.

5) Minor can always plead minority. Even if he has, by misrepresenting his age, induced the

other party to contract with him, he cannot be sued either in contract or in tort for fraud.

The Court may, where a loan or some property is obtained by the minor by some fraudulent

representation and the agreement is set aside, direct him, on equitable consideration, to restore

the money or property to the other party. Whereas the law gives protection to the minors, it does

not give them liberty to cheat men.

6) There can be no specific performance of the agreements entered into by him as they are void

ab initio.

7) Minor cannot enter into a contract of partnership. But he may be admitted to the benefits of

partnership with the consent of other partners.

8) Minor cannot be adjudged as insolvent, because he is incapable of contracting debts.

9) Minor can be an agent, since an agent is merely a link between the principal and the third

party.

10) A contract by a guardian on behalf of the minor is enforceable by or against the minor,

provided the guardian is competent to contract and the contract is beneficial to the minor. But he

cannot purchase immovable property without obtaining the consent of the court.

11) A minor is liable for necessaries supplied to him.

Persons of unsound mind

One of the essential conditions of competency of parties to a contract is that they should be of

sound mind. Sec.12 lays down that A person is said to be of sound mind for the purpose of

making a contract if, at the time when he makes it, he is capable of understanding it and of

forming a rational judgement as to its effect upon his interests.

A person who is usually of unsound mind, but occasionally of sound mind, may make a contract

when he is of sound mind.

A person who is usually of sound mind, but occasionally of unsound mind, may not make a

contract when he is unsound mind.

Soundness of mind of a person depends on:

(i) his capacity to understand the contents of the business concerned, and

(ii) his ability to form a rational judgement as to its effect upon his interests.

If a person is incapable of both, he suffers from unsoundness of mind. Whether a party to a

contract is of sound mind or not is a question of fact to be decided by the Court.

Contracts of Persons on Unsound Mind

Lunatics: A lunatic is a person who is mentally deranged due to some mental strain or other

personal experience. He suffers from intermittent intervals of sanity and insanity. He can enter

into contract during the period when he is sane and the contract is valid. The contract entered

during the period of insanity is not valid.

Idiots: An idiot is a person who has only physical maturity but not mental maturity. For instance,

an individual of age 25 can have the brain growth of only 10 years old. Hence he cannot

understand the nature of the transactions. Idiocy is permanent. An agreement with an idiot is

void.

Drunkard: A drunkard person suffers from temporary incapacity to contract, i.e. at the time when

he is incapable of forming a rational judgement. He can enter into a valid contract when he is

normal, and the contract entered during the period of intoxication is not valid.

FREE CONSENT

Consent: It means an act of assenting to an offer. According to Sec.13 Two or more persons

are said to consent when they agree upon the same thing in the same sense.

Free Consent: Consent is said to be free when it is not caused by

(1) Coercion as defined in Sec. 15, or

(2) Undue influence as defined in Sec. 16, or

(3) Fraud as defined in Sec. 17, or

(4) Misrepresentation as defined in Sec. 18, or

(5) Mistake, subject to the provisions of Secs.20, 21 and 22 (Sec.14).

When there is no consent, there is no contract.

Example: A is forced to sign a promissory note at the point of pistol. A knows what he is signing

but his consent is not free. The contract in this case is voidable at his option. flaw in consent

Coercion Undue influence Misrepresentation Mistake (Sec. 15) (Sec. 16)

Fraudulent or Innocent or Willful (Sec. 17) unintentional (Sec. 18)

Mistake of law Mistake of fact (Sec. 21) (Sec. 20)

Coercion

Coercion is the committing, or threatening to commit, any act forbidden by the Indian Penal

Code, 1860 or the unlawful detaining, or threatening to detain, any property, to the prejudice of

any person whatever, with the intention of causing any person to enter into an agreement.

When a person is compelled to enter into a contract by the use of force by the other party or

under a threat, coercion is said to be employed.

The threat amounting to coercion need not necessarily proceed from a party to the contract. It

may proceed even from a stranger to the contract.

Example: A threatens to kill B if he does not lend Rs.1000 to C. B agrees to lend the amount to

C. The agreement is entered into under coercion.

Consent is said to be caused when it is obtained by:

1) Committing or threatening to commit any act forbidden by the Indian Penal Code.

Ranganayakamma Vs Alwar Chetti: A young girl of 13 years was forced to adopt a boy to her

husband who had just died by the relativesof the husband who prevented the removal of his

body for cremation until she consented. Held, the consent was not free but was induced by

coercion.

2) Unlawful detaining or threatening to detain any property

Muthiah Vs Muthu Karuppan: An agent refused to hand over the account books of a business to

the new agent unless the principal released him from all liabilities. The principal had to give a

release deed asdemanded. Held, the release deed was given under coercion and was voidable

at the option of the Principal.

Undue influence

Sometimes a party is compelled to enter into an agreement against his will as a result of unfair

persuasion by the other party. This happens when a special kind of relationship exists between

the parties such that one party is in a dominant position to exercise undue influence over the

other.

Sec. 16(1) defines undue influence as follows:

A contract is said to be induced by undue influence where the relations subsisting between the

parties are such that one of the parties is in a position to dominate the will of the other and uses

that position to obtain an unfair advantage over the other.

The following relationships usually raise a presumption of undue influence, viz.,

(i) teacher and student,

(ii) guardian and ward,

(iii) trustee and beneficiary,

(iv) religious adviser and disciple,

(v) doctor and patient,

(vi) solicitor and client.

The presumption of undue influence applies whenever the relationship between the parties is

such that one of them is, by reason of confidence reposed on him by the other, able to take

unfair advantage over the other.

A person is deemed to be in a position to dominate the will of another where:

he holds a real or apparent authority over the other, e.g. the relationship between teacher

and the student.

he stands in a fiduciary relation (relation of trust and confidence) to the other. It is supposed

to exist, for example, between solicitor and client, trustee and beneficiary.

he makes a contract with a person whose mental capacity is temporarily or permanently

affected by reason of age, illness or mental or bodily distress. Such a relation exists, for

example, between a medical attendant and his patient.

Example: A spiritual guru induced his devotee to gift to him the whole of his property in return of

a promise of salvation of the devotee. Held, the consent of the devotee was given under undue

influence. (Mannu Singh Vs. Umadat Pandey).

Effect of undue influence

When consent to an agreement is obtained by undue influence, the contract is voidable at the

option of the party whose consent was so obtained.

Example: A money lender advances Rs.1000 to B, and agriculturist and by undue influence

induces B to execute a bond for Rs.2000 with interest at 6 per cent per month. The Court may

set the bond aside, ordering B to repay Rs.1000 with such interest as may seem to it

reasonable.

Difference between coercion and undue influence

1. The consent is obtained under the threat of an offence.

The consent is obtained by a person who is in a position to dominate the will of another.

2. Coercion is mainly of a physical character. It involves mostly use of physical or violent force.

Undue influence involves use of moral force or mental pressure to obtain the consent.

3. There must be intention of causing physical harm to any person to enter into an agreement.

Here the influencing party uses its position to obtain an unfair advantage over the other party.

4. It involves a criminal act. It involves unlawful act.

Misrepresentation and fraud

A statement of fact which one party makes in the course of negotiations with a view to inducting

the other party to enter into a contract is known as representation.

misrepresentation

A representation, when wrongly made is a misrepresentation.

A misrepresentation may be (i) innocent misrepresentation (ii) willful misrepresentation or fraud.

Innocent misrepresentation is a false statement which the person making it honestly believes to

be true or which he does not know to be false. It also includes non-disclosure of a material fact

or facts without any intent to deceive the other party.

Sec. 18 defines misrepresentation. According to it, there is misrepresentation:

(1) When a person positively asserts that a fact is true when his information does not warrant it

to be so though he believes is to be true.

(2) When there is any breach of duty by a person which brings an advantage to the person

committing it by misleading another to his prejudice.

(3) When a party causes, however innocently, the other party to the agreement to make a

mistake as to the substance of the thing which is the subject of the agreement.

Example: A told his wife within the hearing of their daughter that the bridegroom proposed for

her was a young man. The bridegroom, however, was over sixty years. The daughter gave her

consent to marry him believing the statement by her father. Held, the consent was vitiated by

misrepresentation and fraud.

Consequences of Misrepresentation

The aggrieved party, in case of misrepresentation by the other party, can

1) avoid or rescind the contract; or

2) accept the contract but insist that he shall be placed in the position in which he would have

been if the representation made had been true.

Fraud

Fraud exists when it is shown that a false representation has been made (a) knowingly, or (b)

without belief in its truth, or (c) recklessly, not caring whether it is true or false, and the maker

intended the other party to act upon it, or,

There is a concealment of a material fact or that there is a partial statement of a fact in such a

manner that the withholding of what is not stated makes that which is stated false.

The intention of the party making fraudulent misrepresentation must be to deceive the other

party to the contract or to induce him to enter into a contract.

According to Sec.17, fraud means and includes any of the following acts committed by a party

to a contract, or with his connivance, or by his agent with intent to deceive or to induce a person

to enter into a contract:

1. The suggestion that a fact is true when it is not true and the person making the suggestion

does not believe it to be true;

2. The active concealment of a fact by a person having knowledge or belief of the fact;

3. A promise made without any intention of performing it;

4. Any other act or omission as the law specifically declares to be fraudulent.

LEGALITY OF OBJECT

A contract must have a lawful object. The word object means purpose or design. In some

cases, consideration for an agreement may be lawful but the purpose for which the agreement

is entered into may be unlawful. In such cases the agreement is void. As such, both the object

and the consideration of an agreement must be lawful, otherwise the agreement is void.

Sec. 23. The consideration or object of an agreement is unlawful

1. If the object is forbidden by law.

Example: A promises to obtain for B an employment in the public service and B promises to pay

Rs.1,00,000 to A. The agreement is void, as the consideration is unlawful.

2. If the object is permitted, it would defeat the provisions of any law.

Example: N agreed to enter a companys service in consideration of a weekly wage of Rs.75

and a weekly expense allowance of Rs.25. Both the parties knew that the expense allowance

was a device to evade tax. Held, the agreement was unlawful.

3. If the object is fraudulent. An agreement which is made for a fraudulent purpose is void. Thus

an agreement in fraud of creditors with a view to defeating their rights is void.

4. If it involves or implies injury to the person or property of the another. Injury means wrong,

harm of damage.

5. If the consideration or the object is immoral.

Example: A agrees to let her daughter to B for concubinage (state of living together as man and

wife without being married). The agreement is unlawful, being immoral.

6. Where the object is opposed to public policy.

Unlawful and illegal agreements

An unlawful agreement is one which, like a void agreement, is not enforceable by law. An illegal

agreement, is not only void as between the immediate parties but also makes the collateral

transactions void.

Example: L lends Rs.50,000 to B to help him to purchase some prohibited goods from T, an

alien enemy. If B enters into an agreement with T, the agreement will be illegal and the

agreement between B and L shall also become illegal, because it is collateral to the main

transaction. L cannot, therefore, recover the amount.

Every illegal agreement is unlawful, but every unlawful agreement is not necessarily illegal.

Illegal acts are those which involve the commission of a crime or contain an element of obvious

moral turpitude and forbidden by law. On the other hand, unlawful acts are those which are less

rigorous in effect and involve a non-criminal breach of law. These acts do not affect public

morals, nor do they result in the commission of a crime. These are simply disapproved by law

on some ground of public policy.

Effects of Illegality

The general rule of law is that no action is allowed on an illegal agreement and the law will not

help both the parties to the agreement. agreements opposed to public policy

An agreement is said to be opposed to public policy when it is harmful to the public welfare.

Some of the agreements which are opposed to public policy and are unlawful are as follows:

1. Agreements of trading with enemy. An agreement made with an alien enemy in time of war is

illegal on the ground of public policy.

2. Agreement to commit a crime. Where the consideration in an agreement is to commit a crime,

the agreement is opposed to public policy. The Court will not enforce such an agreement.

3. Agreements which interfere with administration of justice. An agreement, the object of which

is to interfere with the administration of justice is unlawful, being opposed to public policy. It may

take any of the following forms:

(a) Interference with the course of justice. An agreement which obstructs the ordinary process of

justice is unlawful.

(b) Stifling prosecution. It is in public interest that if a person has committed a crime, he must be

prosecuted and punished.

(c) Maintenance and champerty. Maintenance is an agreement to give assistance, financial or

otherwise, to another to enable him to bring or defend legal proceedings when the person giving

assistance has got no legal interest of his own in the subject-matter.

4. Agreements in restraint of legal proceedings. Sec. 28 which deals with these agreements:

(a) Agreements restricting enforcement of rights. An agreement which wholly or partially

prohibits any party from enforcing his rights under or in respect of any contract is void to that

extent.

(b) Agreements curtailing period of limitation. Agreements which curtail the period of limitation

prescribed by the Law of Limitation are void because their object is to defeat the provisions of

law.

5. Trafficking in public offices and titles. Agreements for the sale or transfer of public offices and

titles or for the procurement of a public recognition like Padma Vibhushan or Param Veer

Chakra for monetary consideration are unlawful, being opposed to public policy.

Example: R paid a sum of Rs.2,50,000 to A who agreed to obtain a seat for Rs son in a Medical

College.

On As failure to get the seat, R filed a suit for the refund of Rs.2,00,000. Held, the agreement

was against public policy.

6. Agreements tending to create interest opposed to duty. If a person enters into an agreement

whereby he is bound to do something which is against his public or professional duty, the

agreement is void on the ground of public property.

7. Agreements in restraint of parental rights. A father, and in his absence the mother, is the legal

guardian of his/her minor child. This right of guardianship cannot be bartered away by any

agreement.

8. Agreements restricting personal liberty. Agreements which unduly restrict the personal

freedom of the parties to it are void as being against public policy.

9. Agreements in restraint of marriage. Every agreement in restraint of the marriage of any

person, other than a minor, is void (Sec. 26). This is because the law regards marriage and

married status as the right of every individual.

10. Marriage brokerage agreements. An agreement by which a person, for a monetary

consideration, promises in return to procure the marriage of another is void, being opposed to

public policy.

11. Agreements interfering with marital duties. Any agreement which interferes with the

performance of marital duties is void, being opposed to public policy. Such agreements have

been held to include the following:

(a) A promise by a married person to marry, during the lifetime or after the death of spouse.

(b) An agreement in contemplation of divorce, e.g. an agreement to lend money to a woman in

consideration of her getting a divorce and marrying the lender.

(c) An agreement that the husband and wife will always stay at the wifes parents house and

that the wife will never leave her parental house.

12. Agreements to defraud creditors or revenue authorities. An agreement the object of which is

to defraud the creditors or the revenue authorities is not enforceable, being opposed to public

policy.

13. Agreements in restraint of trade. An agreement which interferes with the liberty of a person

to engage himself in any lawful trade, profession or vocation is called an agreement in restraint

of trade.

Oakes & Co. Vs Jackson: An agreement between an employee and the company whereby the

employee agrees not to work in a similar company within a distance of 800 miles from Madras

after leaving the employment, is held void.

CONTINGENT CONTRACTS

Contingent means that which is dependent on something else. A Contingent Contract is a

contract to do or not to do something, if some event, collateral to such contract, does or does

not happen (Sec. 31). For example, goods are sent on approval, the contract is a contingent

contract depending on the act of the buyer to accept or reject the goods.

There are three essential characteristics of a contingent contract:

1. Its performance depends upon the happening or non-happening in future of some event. It is

this dependence on a future event which distinguishes a contingent contract from other

contracts.

2. The event must be uncertain. If the event is bound to happen, and the contract has got to be

performed in any case it is not a contingent contract.

3. The event must be collateral, i.e. incidental to the contract.

Contracts of insurance, indemnity and guarantee are the commonest instances of a contingent

contract.

Rules regarding contingent contracts

1. Contingent contracts dependent on the happening of an uncertain future event cannot be

enforced until the event has happened. If the event becomes impossible, such contracts

become void (Sec. 32).

Example: A contracts to pay B a sum of money when B marries C. C dies without being married

to B.

The contract becomes void.

2. Where a contingent contract is to be performed if a particular event does not happen, its

performance can be enforced when the happening of that event becomes impossible (Sec. 33).

Example: A agrees to pay B a sum of money, if a certain ship does not return. The ship is sunk.

The contract can be enforced when the ship sinks.

3. If a contract is contingent upon how a person will act at an unspecified time, the event shall

be considered to become impossible when such person does anything which renders it

impossible that he should so act within any definite time, or otherwise than under further

contingencies (Sec. 34).

Example: A agrees to pay B a sum of money if B marries C. C marries D. The marriage of B to

C must now be considered impossible, although it is possible that D may die and that C may

afterwards marry B.

4. Contingent contracts to do or not to do anything, if a specified uncertain event happens within

a fixed time, become void if the event does not happen or its happening becomes impossible

before the expiry of that time.

Example: A promises to pay B a sum of money if a certain ship returns within a year. The

contract may be enforced if the ship returns within the year, and becomes void if the ship is

burnt within the year.

5. Contingent agreements to do or not to do anything, if an impossible event happens, are void,

whether or not the fact is known to the parties (Sec. 36).

Example: A agrees to pay B Rs.1,000 if B will marry As daughter, C. C was dead at the time of

the agreement. The agreement is void.

PERFORMANCE OF CONTRACT

Performance of a contract takes place when the parties to the contract fulfil their obligations

arising under the contract within the time and in the manner prescribed.

Offer to perform

Sometimes it so happens that the promisor offers to perform his obligation under the contract at

the proper time and place but the promisee does not accept the performance. This is known as

attempted performance or tender. Thus, a tender of performance is equivalent to actual

performance.

Requisites of a valid tender

1. It must be unconditional. It becomes conditional when it is not in accordance with the terms of

the contract.

2. It must be of the whole quantity contracted for or of the whole obligation. A tender of an

instalment when the contract stipulates payment in full is not a valid tender.

3. It must be by a person who is in a position, and is willing, to perform the promise.

4. It must be made at the proper time and place. A tender of goods after the business hours or

of goods or money before the due date is not a valid tender.

5. It must be made to proper person, i.e. the promisee or his duly authorised agent. It must also

be in proper form.

6. It may be made to one of the several joint promisees. In such a case it has the same effect as

a tender to all of them.

7. In case of tender of goods, it must give a reasonable opportunity to the promisee for

inspection of goods.

8. In case of tender of money, the debtor must make a valid tender in the legal tender money.

Contracts which need not be performed

A contract need not be performed

1. When its performance becomes impossible.

2. When the parties to it agree to substitute a new contract for it or to rescind or alter it.

3. When the promisee dispenses with or remits, wholly or in part, the performance of the

promise made to him or extends the time for such performance or accepts any satisfaction for it.

4. When the person at whose option it is voidable, rescindsit.

5. When the promisee neglects or refuses to afford the promisor resonable the facilities for the

performance of his promisee.

Example: A contracts with B to repair Bs house. A neglects or refuses to point out to A the

places in which his house requires repairs. B is excused for the non-performance of the

contract, if it is caused by such neglect or refusal.

6. When it is illegal.

TERMINATION AND DISCHARGE OF CONTRACT

Discharge of contract means termination of the contractual relationship between the parties. A

contract is said to be discharged when it ceases to operate, i.e. when the rights and obligations

created by it come to an end.

A contract may be discharged

1. By Performance

2. By Agreement or Consent

3. By Impossibility

4. By Lapse of Time

5. By Operation of Law

6. By Breach of Contract

1. Discharge by performance

Performance means the doing of that which is required by a contract. Discharge by performance

takes place when the parties to the contract fulfil their obligations arising under the contract

within the time and in the manner prescribed.

Performance of a contract is the most usual mode of its discharge. It may be

(1) Actual Performance: When both the parties perform their promises, the contract is

discharged.

Performance should be complete, precise and according to the terms of the agreement.

(2) Attempted Performance or Tender: Tender is not actual performance, but is only an offer to

perform the obligation under the contract.

2. Discharge by agreement or consent

Sec. 62 lays down that if the parties to a contract agree to substitute a new contract for it, or to

rescind or to alter it, the original contract is discharged and need not be performed.

The various cases of discharge of contract by mutual agreement are dealt with in Secs. 62 and

63 are given below:

(a) Novation (Sec. 62): Novation takes place when a new contract is substituted for an existing

one between the same parties.

Example: A owes money to B under a contract. It is agreed between A, B and C that B shall

henceforth accept C as his debtor, instead of A. The old debt of A to B is at an end, and a new

debt from C to B has been contracted.

(b) Rescission (Sec. 62): Rescission of a contract takes place when all or some of the terms of

the contract are cancelled. It may occur

(i) by mutual consent of the parties, or

(ii) where one party fails in the performance of his obligation. In such a case, the other party

may rescind the contract without prejudice to his right to claim compensation for the breach of

contract.

Example: A promises to supply certain goods to B six months after date. By that time, the goods

go out of fashion. A and B may rescind the contract.

(c) Alteration (Sec. 62): Alteration of a contract may take place when one or more of the terms

of the contract is/are altered by the mutual consent of the parties to the contract. In such a case,

the old contract is discharged.

Example: A enters into a contract with B for the supply of 100 bales of cotton at his Godown

No.1 by the first of the next month. A and B may alter the terms of the contract by mutual

consent.

(d) Remission (Sec. 63): Remission means acceptance of a lesser fulfilment of the promise

made, i.e. acceptance of a lesser sum than what was contracted for, in discharge of the whole

of the debt.

Example: A owes B Rs.50,000. A pays to B and B accepts, in satisfaction of the whole debt,

Rs.20,000 paid at the time and place at which Rs.50,000 were payable. The whole debt is

discharged.

(e) Waiver: Waiver takes place when the parties to a contract agree that they shall no longer be

bound by the contract. This amounts to a mutual abandonment of rights by the parties to the

contract.

(f) Merger: Merger takes place when an inferior right accruing to a party under a contract

merges into a superior right accruing to the same party under the same or some other contract.

Example: P holds a property under a lease. He later buys the property. His rights as a lessee

merge into his rights as an owner.

3. Discharge by impossibility of performance

If an agreement contains an undertaking to perform an impossibility, it is void ab initio. This rule

is based on the following maxims:

1. Impossibility existing at the time of agreement. Sec. 56 lays down that an agreement to do

an impossible act itself is void. This is known as pre-contractual or initial impossibility.

2. Impossibility arising subsequent to the formation of contract. Impossibility which arises

subsequent to the formation of a contract (which could be performed at the time when the

contract was entered into) is called post-contractual or supervening impossibility.

Discharge by Supervening Impossibility

A contract is discharged by supervising impossibility in the following cases:

1. Destruction of subject-matter of contract: When the subject-matter of a contract, subsequent

to its formation, is destroyed without any fault of the parties to the contract, the contract is

discharged.

Example: C let a music hall to T for a series of concerts on certain days. The hall was

accidentally burnt down before the date of the first concert. Held, the contract was void.

2. Non-existence or Non-occurrence of a particular state of things: Sometimes, a contract is

entered into between two parties on the basis of a continued existence or occurrence of a

particular state of things. If there is any change in the state of things which ought to have

occurred does not occur, the contract is discharged.

Example: A and B contract to marry each other. Before the time fixed for the marriage, A goes

mad.

The contract becomes void.

3. Death or Incapacity for personal service: Where the performance of a contract depends on

the personal skill or qualification of a party, contract is discharged on the illness or incapacity or

death of that party. The mans life is an implied condition of the contract.

Example: An artist undertook to perform at a concert for a certain price. Before she could do so,

she was taken seriously ill. Held, she was discharged due to illness.

4. Change of law. When, subsequent to the formation of a contract, change of law takes place,

and the performance of the contract becomes impossible, the contract is discharged.

Example: D enters into a contract with P on 1st March for the supply of certain imported goods in

the month of September of the same year. In June by an Act of Parliament, the import of such

goods is banned. The contract is discharged.

5. Outbreak of war. A contract entered into with an alien enemy during war is unlawful and

therefore impossible for performance. Contracts entered into before the outbreak of war are

suspended during the war and may be revived after the war is over.

4. Discharge by lapse of time

The Limitation Act, 1963 lays down that a contract should be performed within a specific period,

called period of limitation. If it is not performed, and if no action is taken by the promisee within

the period of limitation, he is deprived of his remedy at law. For example, the price of goods sold

without any stipulation as to credit should be paid within three years of the delivery of the goods.

If the price is not paid and creditor does not file a suit against the buyer for the recovery of price

within three years, the debt becomes time-barred and hence irrecoverable.

5. Discharge by operation of law

A contract may be discharged by operation of law. This includes discharge

(a) By Death: In contracts involving personal skill or ability, the contract is terminated on death

of the promisor. In other contracts, the rights and liabilities of a deceased person pass on to the

legal representatives of the deceased person.

(b) By Merger: When an inferior right accruing to a party merges into a superior right accruing to

the same party under the same or some other contract, the inferior right accruing to the party is

said to be discharged.

(c) By Insolvency: When a person is adjudged insolvent, he is discharged from all liabilities

incurred prior to his adjudication.

(d) By Unauthorised Alteration of the terms of a Written Agreement: Where a party to a contract

makes any material alteration in the contract without the consent of the other party, the other

party can avoid the contract. A material alteration is one which changes, in a significant manner,

the legal identity or character of the contract or the rights and liabilities of the parties to the

contract.

(e) By Rights and Liabilities becoming vested in the Same Person: Where the rights and

liabilities under a contract vested in the same person, for example when a bill gets into the

hands of the acceptor, the other parties are discharged.

6. Discharge by breach of contract

Breach of contract means a breaking of the obligation which a contract imposes. It occurs when

a party to the contract without lawful excuse does not fulfil his contractual obligation or by his

own act makes it impossible that he should perform his obligation under it. It confers a right of

action for damages on the injured party.

REMEDIES FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT

When a contract is broken, the injured party has one or more of the following remedies:

1. Rescission of the contract

2. Suit for damages

3. Suit upon quantum meruit

4. Suit for specific performance of the contract

5. Suit for injunction.

1. rescission

When a contract is broken by one party, the other party may sue to treat the contract as

rescinded and refuse further performance. In such a case, he is absolved of all his obligations

under the contract.

Example: A promises B to supply 10 bags of cement on a certain day. B agrees to pay the price

after the receipt of the goods. A does not supply the goods. B is discharged from liability to pay

the price.

The Court may grant rescission

(a) where the contract is voidable by the plaintiff; or

(b) where the contract is unlawful for causes not apparent on its face and the defendant is more

to blame than the plaintiff.

When a party treats the contract as rescinded, he makes himself liable to restore any benefits

he has received under the contract to the party from whom such benefits were received. But if a

person rightfully rescinds a contract he is entitled to compensation for any damage which he

has sustained through non-fulfilment of the contract by the other party.

2. damages

Damages are a monetary compensation allowed to the injured party by the Court for the loss or

injury suffered by him by the breach of a contract. The object of awarding damages for the

breach of a contract is to put the injured party in the same position, so far as money can do it,

as if he had not been injured, i.e. in the position in which he would have been had there been

performance and not breach. This is called the doctrine of restitution.

The rules relating to damages may be considered as under:

1. Damages arising naturally Ordinary damages

When a contract has been broken, the injured party can recover from the other party such

damages as naturally and directly arose in the usual course of things from the breach. This

means that the damages must be the proximate consequence of the breach of contract. These

damages are known as ordinary damages.

Example: A contracts to sell and deliver 50 quintals of Farm Wheat to B at Rs.1000 per quintal,

the price to be paid at the time of delivery. The price of wheat rises to Rs.1200 per quintal and A

refuses to sell the wheat. B can claim damages at the rate of Rs.200 per quintal.

2. Damages in contemplation of the parties Special damages

Special damages can be claimed only under the special circumstances which would result in a

special loss in case of breach of a contract. Such damages, known as special damages, cannot

be claimed as a matter of right.

Example: A, a builder, contracts to erect a house for B by the 1st of January, in order that B may

give possession of it at that time to C to whom B has contracted to let it. A is informed of the

contract between B and C. A builds the house so badly that before the 1st January, it falls down

and has to be rebuilt by B, who, in consequence, loses the rent which he was to have received

from C, and is obliged to make compensation to C for the breach of the contract. A must make

compensation to B for the cost of rebuilding the house, for the rent lost, and for the

compensation made to C.

3. Vindictive or Exemplary damages

Damages for the breach of a contract are given by way of compensation for loss suffered, and

not by way of punishment for wrong inflicted. Hence, vindictive or exemplary damages have

no place in the law of contract because they are punitive (involving punishment) by nature. But

in case of (a) breach of a promise to marry, and (b) dishonour of a cheque by a banker

wrongfully when he possesses sufficient funds to the credit of the customer, the Court may

award exemplary damages.

4. Nominal damages

Where the injured party has not in fact suffered any loss by reason of the breach of a contract,

the damages recoverable by him are nominal. These damages merely acknowledge that the

plaintiff has proved his case and won.

Example: A firm consisting of four partners employed B for a period of two years. After six

months two partners retired, the business being carried on by the other two. B declined to be

employed under the continuing partners. Held, he was only entitled to nominal damages as he

had suffered no loss.

5. Damages for loss of reputation

Damages for loss of reputation in case of breach of a contract are generally not recoverable. An

exemption to this rule exists in the case of a banker who wrongfully refuses to honour a

customers cheque. If the customer happens to be a tradesman, he can recover damages in

respect of any loss to his trade reputation by the breach. And the rule of law is: the smaller the

amount of the cheque dishonoured, the larger the amount of damages awarded. But if the

customer is not a tradesman, he can recover only nominal damages.

6. Damages for inconvenience and discomfort

Damages can be recovered for physical inconvenience and discomfort. The general rule in this

connection is that the measure of damages is not affected by the motive or the manner of the

breach.

Example: A was wrongfully dismissed in a harsh and humiliating manner by G from his

employment. Held, (a) A could recover a sum representing his wages for the period of notice

and the commission which he would have earned during that period; but (b) he could not

recover anything for his injured feelings or for the loss sustained from the fact that his dismissal

made it more difficult for him to obtain employment.

7. Mitigation of damages

It is the duty of the injured party to take all reasonable steps to mitigate the loss caused by the

breach. He cannot claim to be compensated by the party in default for loss which he ought

reasonably to have avoided. That is he cannot claim compensation for loss which is really due

not to the breach, but due to his own neglect to mitigate the loss after the breach.

8. Difficulty of Assessment

Although damages which are incapable of assessment cannot be recovered, the fact that they

are difficult to assess with certainty or precision does not prevent the aggrieved party from

recovering them.

The Court must do its best to estimate the loss and a contingency may be taken into account.

Example: H advertised a beauty competition by which readers of certain newspapers were to

select fifty ladies. He himself was to select twelve out of these fifty. The selected twelve were to

be provided theatrical engagements. C was one of the fifty and by Hs breach of contract she

was not present when the final section was made. Held, C was entitled to damages although it

was difficult to assess them.

9. Cost of Decree

The aggrieved party is entitled, in addition to damages, to get the cost of getting the decree for

damages. The cost of suit for damages is in the discretion of the Court.

10. Damages agreed upon in advance in case of breach

If a sum is specified in a contract as the amount to be paid in case of its breach, or if the

contract contains any other stipulation by way of a penalty for failure to perform the obligations,

the aggrieved party is entitled to receive from the party who has broken the contract, a

reasonable compensation not exceeding the amount so mentioned.

Example: A contracts with B to pay Rs.1000 if he fails to pay B Rs.500 on a given day. B is

entitled to recover from A such compensation not exceeding Rs.1000 as the Court considers

reasonable.

Liquidated Damages and Penalty

Sometimes parties to a contract stipulate at the time of its formation that on the breach of the

contract by either of them, a certain specified sum will be payable as damages. Such a sum

may amount to either liquidated damages or a penalty. Liquidated damages represent a sum,

fixed or ascertained by the parties in the contract, which is a fair and genuine pre-estimate of

the probable loss that might arise as a result of the breach, if it takes place. A penalty is a sum

named in the contract at the time of its formation, which is disproportionate to the damage likely

to accrue as a result of the breach. It is fixed up with a view to securing the performance of the

contract.

Payment of Interest

The largest number of cases decided under Sec. 74 relate to stipulations in a contract providing

for payment of interest. The following rules are observed with regard to payment of interest:

1. Payment of interest in case of default.

2. Payment of interest at higher rate

(a) from the date of the bond, and

(b) from the date of default.

3. Payment of compound interest on default

(a) at the same rate as simple interest, and

(b) at the rate higher than simple interest.

4. Payment of interest at a lower rate, if interest paid on due date.

3. quantum meruit

The phrase quantum meruit literally means as much as earned. A right to sue on a quantum

meruit arises where a contract, partly performed by one party, has become discharged by the

breach of the contract by the other party.

4. specific performance

In certain cases of breach of contract, damages are not an adequate remedy. The Court may, in

such cases, direct the party in breach to carry out his promise according to the terms of the

contract. Some of the cases in which specific performance of a contract may, in discretion of the

Court, be enforced are as follows:

(a) When the act agreed to be done is such that compensation in money for its non-

performance is not an adequate relief.

(b) When there exists no standard for ascertaining the actual damage caused by the non-

performance of the act agreed to be done.

(c) When it is probable that the compensation in money cannot be got for the non-performance

of the act agreed to be done.

5. injunction Where a party is in breach of a negative term of a contract (i.e. where he is doing

something which he promised not to do), the Court may, by issuing an order, restrain him from

doing what he promised not to do. Such an order of the Court is known as injunction.

Example: W agreed to sing at Ls theatre, and during a certain period to sing nowhere else.

Afterwards W made contract with Z to sing at another theatre and refused to perform the

contract with L.

Held, W could be restrained by injunction from singing for Z.

QUASI CONTRACTS

Under certain circumstances, a person may receive a benefit to which the law regards another

person as better entitled, or for which the law considers he should pay to the other person, even

though there is no contract between the parties. Such relationships are termed quasi-contracts,

because, although there is no contract or agreement between the parties, they are put in the

same position as if there were a contract between them. These relationships are termed as

quasi-contracts.

A quasi-contract rests on the ground of equity that a person shall not be allowed to enrich

himself unjustly at the expense of another. The principle of unjust enrichment requires:

that the defendant has been enriched by the receipt of a benefit;

that this enrichment is at the expense of the plaintiff; and

that the retention of the enrichment is unjust.

Law of quasi-contracts is also known as the law of restitution. Strictly speaking, a quasi-contract

is not a contract at all. A contract is not intentionally entered into. A quasi-contract, on the other

hand, is created by law.

Kinds of quasi contracts

1. Supply of necessaries (Sec. 68)

If a person, incapable of entering into a contract, or anyone whom he is legally bound to

support, is supplied by another with necessaries suited to his condition in life, the person who

has furnished such supplies is entitled to be reimbursed from the property of such incapable

person.

Example: A supplies B, a lunatic, with necessaries suitable to his condition in life. A is entitled to

be reimbursed from Bs property.

2. Payment by an interested person (Sec. 69)

A person who is interested in the payment of money which another is bound by law to pay, and

who therefore pays it, is entitled to be reimbursed by the other.

Example: P left his carriage on Ds premises. Ds landlord seized the carriage as distress for

rent. P paid the rent to obtain the release of his carriage. Held, P could recover the amount from

D.

The essential requirements are as follows:

(a) The payment made should be bonafide for the protection of ones interest.

(b) The payment should not be voluntary one.

(c) The payment must be such as the other party was bound by law to pay.

3. Obligation to pay for non-gratuitous acts (Sec. 70)

When a person lawfully does anything for another person or delivers anything to him, not

intending to do so gratuitously, and such other person enjoys the benefit thereof, the latter is

bound to make compensation to the former in respect of, or to restore, the thing so done or

delivered.

Example: A, a tradesman, leaves goods at Bs house by mistake. B treats the goods as his own.

He is bound to pay for them to A.

Before any right of action under Sec. 70 arises, three conditions must be satisfied:

(a) The thing must have been done lawfully.

(b) The person doing the act should not have intended to do it gratuitously.

(c) The person for whom the acts is done must have enjoyed the benefit of the act.

4. Responsibility of finder of goods (Sec. 71)

A person, who finds goods belonging to another and takes them into his custody, is subject to

the same responsibility as a bailee. He is bound to take as much care of the goods as a man of

ordinary prudence would, under similar circumstances, take of his own goods of the same bulk,

quality and value.

He must also take all necessary measures to trace its owner. If he does not, he will be guilty of

wrongful conversion of the property. Till the owner is found out, the property in goods will vest in

the finder and he can retain the goods as his own against the whole world (except the owner).

Example: F picks up a diamond on the floor of Ss shop. He hands it over to S to keep it till true

owner is found out. No one appears to claim it for quite some weeks in spite of the wide

advertisements in the newspapers. F claims the diamond from S who refuses to return. S is

bound to return the diamond to F who is entitled to retain the diamond against the whole world

except the true owner.

The finder can sell the goods in the following cases:

when the thing found is in danger of perishing;

when the owner cannot, with reasonable diligence, be found out;

when the owner is found out, but he refuses to pay the lawful charges of the finder; and

when the lawful charges of the finder, in respect of the thing found, amount to two-thirds of

the value of the thing found. (Sec. 169).

5. Mistake or coercion (Sec. 72)

A person to whom money has been paid, or anything delivered, by mistake or under coercion,