Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Operational Research Question

Hochgeladen von

Matin Ahmad KhanCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Operational Research Question

Hochgeladen von

Matin Ahmad KhanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

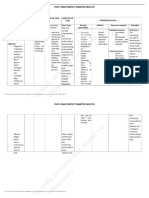

OPERATIONAL RESEARCH QUESTION

How early to start antiretroviral therapy (i.e. at what CD4 count level) among HIV-

infected TB patients, to achieve maximum reduction in the risk of developing TB?

Without treatment, most HIV-infected individuals will eventually develop progressive

immunosuppression, as evident by CD4 T lymphocyte (CD4) cell depletion, leading to AIDS-defining

illnesses and premature death. The primary goal of ART is to prevent HIV-associated morbidity and

mortality. This goal is best accomplished by using effective ART to maximally inhibit HIV replication so

that plasma HIV RNA (viral load) remains below levels detectable by commercially available assays.

Durable viral suppression improves immune function and overall quality of life, lowers the risk of both

AIDS-defining and non-AIDS-defining complications, and prolongs life.

Furthermore, high plasma HIV RNA is a major risk factor for HIV transmission, and effective antiretroviral

therapy (ART) can reduce viremia and transmission of HIV to sexual partners by more than

96%.

2

Modelling studies suggest that expanded use of ART may result in lower incidence and,

eventually, prevalence of HIV on a community or population level. Thus, a secondary goal of ART is to

reduce the risk of HIV transmission.

Historically, HIV-infected individuals have had low CD4 counts at presentation to care. However, there

have been concerted efforts to increase testing of at-risk patients and to link these patients to medical

care before they have advanced HIV disease. Deferring ART until CD4 count declines put an individual at

risk of AIDS-defining conditions has been associated with higher risk of morbidity and mortality (as

discussed below). Furthermore, the magnitude of CD4 recovery is directly correlated with CD4 count at

ART initiation. Consequently, many individuals who start treatment with CD4 counts <350

cells/mm

3

never achieve counts >500 cells/mm

3

after up to 6 years on ART.

5

The recommendation to initiate ART in individuals with high CD4 cell countswhose short-term risk for

death and development of AIDS-defining illness is low is based on growing evidence that untreated

HIV infection or uncontrolled viremia is associated with development of non-AIDS-defining diseases,

including cardiovascular disease (CVD), kidney disease, liver disease, neurologic complications, and

malignancies. Furthermore, newer ART regimens are more effective, more convenient, and better

tolerated than regimens used in the past.

Regardless of CD4 count, the decision to initiate ART should always include consideration of a patients

comorbid conditions, his or her willingness and readiness to initiate therapy, and available resources. In

settings where there are insufficient resources to initiate ART in all patients, treatment should be

prioritized for patients with the following clinical conditions: pregnancy; CD4 count <200 cells/mm

3

or

history of an AIDS-defining illness including HIV-associated dementia, HIV-associated nephropathy

(HIVAN), or hepatitis B virus (HBV); and acute HIV infection.

Tempering the enthusiasm to treat all patients regardless of CD4 count is the absence of randomized

trial data that demonstrate a definitive clinical benefit of ART in patients with higher CD4 counts (e.g.,

>350 cells/ mm

3

) and mixed results from observational cohort studies as to the definitive benefits of

early ART (i.e., when CD4 count >500 cells/mm

3

). For some asymptomatic patients, the potential risks of

short- or long-term drug-related complications and non-adherence to long-term therapy may offset

possible benefits of earlier initiation of therapy. An ongoing randomized controlled trial evaluating the

role of immediate versus delayed ART in patients with CD4 counts >500 cells/mm

3

(see Strategic Timing

of Antiretroviral Treatment (START); ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00867048) should help to further

define the role of ART in this patient population.

HIV infection significantly increases the risk of progression from latent to active TB disease. The CD4 cell

count influences both the frequency and severity of active TB disease [1-2]. Active TB also negatively

affects HIV disease. It may be associated with a higher HIV viral load and more rapid progression of HIV

disease [3].

Active pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB disease requires prompt initiation of TB treatment. The

treatment of active TB disease in HIV-infected patients should follow the general principles guiding

treatment for individuals without HIV (AI). Treatment of drug-susceptible TB disease should include a

standard regimen that consists of isoniazid (INH) + a rifamycin (rifampin or rifabutin) + pyrazinamide +

ethambutol given for 2 months, followed by INH + a rifamycin for 4 to 7 months [4]. The Guidelines for

Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and

Adolescents [4] include a more complete discussion of the diagnosis and treatment of TB disease in HIV-

infected patients.

All patients with HIV/TB disease should be treated with ART (AI). Important issues related to the use of

ART in patients with active TB disease include: (1) when to start ART, (2) significant pharmacokinetic

drug-drug interactions between rifamycins and some antiretroviral (ARV) agents, (3) the additive

toxicities associated with concomitant ARV and TB drug use, (4) the development of TB-associated IRIS

after ART initiation, and (5) the need for treatment support including DOT and the integration of HIV and

TB care and treatment.

2. What is the optimal timing and frequency of systematic TB screening among

people living with HIV?

3. What are the barriers to care for people living with HIV, adults, children and

families, to access HIV and TB care, and antiretroviral therapy for those co-

infected with TB, from patient and health-care workers perspective, and how to

address them?

Tuberculosis (TB) and HIV infection are very closely linked, and over a million persons with both

conditions are estimated to need simultaneous treatment for both diseases each year. People

living with HIV (PLHs) have an increased risk of becoming infected and developing TB. Although

TB is curable, it is a leading cause of ill health and death among PLHs. For this reason, early

diagnosis, timely initiation of treatment for both diseases and careful monitoring are essential

to treat TB in PLHs and identify HIV infection in people with TB. The main obstacles to managing

patients with TB and HIV co-infection are weak coordination between TB and HIV programmes

and slow integration of collaborative TB-HIV services into the general health services. These

challenges may have an adverse impact on patients treatment access and outcomes. The

escalating human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis (TB) epidemics have a

significant impact on public health services in resource-limited settings four potential barriers

to treatment use by comparing the reported perceptions and experiences of HIV-positive adults

(age 18+) who have never taken a prescription medicine to treat their HIV (untreated

patients) to those who had begun taking a prescription medicine to treat their HIV in the past

five years (treated patients):

Limited disease-specific knowledge. Untreated patients are less knowledgeable about HIV and

its potential effects than treated patients.

Only 38 percent of untreated patients believe that HIV attacks the immune system and

body even if the person with HIV does not feel sick, compared to 63 percent of treated

patients.

Thirty-nine percent of untreated patients believe the human body has a natural ability

to fight HIV, compared to 16 percent of treated patients.

Limited treatment-specific knowledge. Untreated patients also have limited treatment-specific

knowledge and cite reasons for not using HIV prescription medicine that are inconsistent with

available data or current treatment guidelines.

Data show that HIV-positive patients who take HIV prescription medicine reduce their

risk of transmitting the virus to someone else by 96 percent , but only 25 percent of

untreated patients are aware being on a HIV prescription medicine reduces that risk

Despite its proven efficacy, only 28 percent of untreated patients believe that HIV

prescription medicine controls the negative effects of the disease

Misperceptions regarding treatment use. The reported perceptions of HIV prescription

medicine among untreated patients were somewhat negative and inconsistent with the

reported experiences of treated patients.

Nearly one-third (30 percent) of untreated patients believe that the side effects of HIV

prescription medicine are worse than HIV itself, but only 15 percent of treated patients

report this to be the case

Eighty percent of treated patients believe that their HIV prescription medicine makes

them feel better, and they can focus on the important things in their life, and 56 percent

say that it has had a positive impact on their overall health and well-being. However,

one in five (20 percent) of untreated patients dont currently take HIV prescription

medicine because they believe once they start, theyll need to be on it for the rest of

their lives

Fewer positive perceptions of overall well-being.

Untreated patients are less likely than treated patients to agree that their disease is

well-controlled (84 percent vs. 91 percent) and less likely to agree they will live a full life

despite their HIV (72 percent vs. 83 percent)

Initial review of these parallel programs revealed barriers to optimal care of both HIV-infected

and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infected patients. These barriers are discussed below.

Strict application of ART program guidelines

Requirement of a treatment buddy to accompany the patient to a doctors appointment.

Communications barriers among providers and between providers and patients

Counselors providing ART adherence training

HIV expertise at the inpatient medical service.

Limited patient preparation for TB treatment

TB diagnosis and adherence to TB program guidelines.

Failure of DOTS in the face of human-resource shortages.

Separation from traditional healers

Need for HIV and TB support services.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Artcle Review - by DR.M Tariq Alvi (Ms-Ent)Dokument5 SeitenArtcle Review - by DR.M Tariq Alvi (Ms-Ent)Matin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using Viruses To Fight VirusesDokument2 SeitenUsing Viruses To Fight VirusesMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of Role of CHQ in Prevention in CancerDokument4 SeitenAssessment of Role of CHQ in Prevention in CancerMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MRCP WebsitesDokument1 SeiteMRCP WebsitesMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Worker: Career Information: Dawn Rosenberg MckayDokument4 SeitenSocial Worker: Career Information: Dawn Rosenberg MckayMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clin Chem Lab MedDokument1 SeiteClin Chem Lab MedMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Worker: Career Information: Dawn Rosenberg MckayDokument4 SeitenSocial Worker: Career Information: Dawn Rosenberg MckayMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMSC Thesis 4Dokument7 SeitenMMSC Thesis 4Matin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To HIV CourseDokument9 SeitenIntroduction To HIV CourseMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taher and AbdelhaiDokument11 SeitenTaher and AbdelhaiMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- AIIMS General KnowledgeDokument8 SeitenAIIMS General KnowledgeMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation of Gastric FunctionDokument17 SeitenEvaluation of Gastric FunctionMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Friis Study GuideDokument14 SeitenFriis Study GuideMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sandeep Sachdeva Jagbir S. Malik Ruchi Sachdeva Tilak R. SachdevDokument5 SeitenSandeep Sachdeva Jagbir S. Malik Ruchi Sachdeva Tilak R. SachdevMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MR - Matin Ahmed KhanDokument1 SeiteMR - Matin Ahmed KhanMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- HIV ForensicsDokument12 SeitenHIV ForensicsMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMSC Thesis 1Dokument13 SeitenMMSC Thesis 1Matin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discovery of AidsDokument3 SeitenDiscovery of AidsMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Mosquitoes Cannot Transmit AIDSDokument3 SeitenWhy Mosquitoes Cannot Transmit AIDSMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article Review FormatDokument6 SeitenArticle Review FormatMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discovery of AidsDokument3 SeitenDiscovery of AidsMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- TableDokument2 SeitenTableMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Directorate of Learning Systems Directorate of Learning SystemsDokument50 SeitenDirectorate of Learning Systems Directorate of Learning SystemsMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMSC Thesis 6Dokument38 SeitenMMSC Thesis 6Matin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Specializations Available Hand Book of The ProgramDokument2 SeitenThe Specializations Available Hand Book of The ProgramMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Njem 1Dokument14 SeitenNjem 1Matin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- HIV and SalivaDokument1 SeiteHIV and SalivaMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Based PhD-CEO EditedDokument3 SeitenThesis Based PhD-CEO EditedMatin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMSC Thesis 6Dokument38 SeitenMMSC Thesis 6Matin Ahmad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Scenar Testimonials (Updated)Dokument10 SeitenScenar Testimonials (Updated)Tom Askew100% (1)

- Discuss Ethical and Cultural Consideration in DiagnosisDokument2 SeitenDiscuss Ethical and Cultural Consideration in DiagnosisJames Harlow0% (1)

- Flagile X SyndromeDokument2 SeitenFlagile X Syndromeapi-314093325Noch keine Bewertungen

- TB Caravan GuideDokument22 SeitenTB Caravan GuideMajo Napata100% (1)

- Best IVF Doctors in Delhi With High Success RatesDokument11 SeitenBest IVF Doctors in Delhi With High Success RatesPrabha SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safety Seal Certification ChecklistDokument2 SeitenSafety Seal Certification ChecklistKathlynn Joy de GuiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Pre Experimental Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Planned Teaching Programme On Knowledge Towards Safe Handling of Chemotherapeutics Drugs Among Staff Nurses in C.H.R.I Gwalior M.PDokument6 SeitenA Pre Experimental Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Planned Teaching Programme On Knowledge Towards Safe Handling of Chemotherapeutics Drugs Among Staff Nurses in C.H.R.I Gwalior M.PEditor IJTSRDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Megan Fobar - Case Study AbstractDokument2 SeitenMegan Fobar - Case Study Abstractapi-288109471Noch keine Bewertungen

- Topnotch Pathology Supplemental PICTURES Powerpoint Based On Handouts September 2019Dokument53 SeitenTopnotch Pathology Supplemental PICTURES Powerpoint Based On Handouts September 2019croixNoch keine Bewertungen

- POPS PretestDokument6 SeitenPOPS Pretestkingjameson1Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2 AleDokument10 Seiten2 AleAna María ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- PrimaryCare JAWDA - Update 2022Dokument40 SeitenPrimaryCare JAWDA - Update 2022SECRIVINoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Chronic PainDokument8 SeitenJournal of Chronic PainRirin TriyaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Local AnestheticDokument4 SeitenLocal AnestheticAndrea TrescotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study 10Dokument4 SeitenCase Study 10Rachael OyebadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- dm2020 0202 PDFDokument6 Seitendm2020 0202 PDFcode4saleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gi-Rle - NCP For Deficient Fluid VolumeDokument2 SeitenGi-Rle - NCP For Deficient Fluid VolumeEvangeline Villa de Gracia100% (1)

- Discontinuing β-lactam treatment after 3 days for patients with community-acquired pneumonia in non-critical care wards (PTC) : a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trialDokument9 SeitenDiscontinuing β-lactam treatment after 3 days for patients with community-acquired pneumonia in non-critical care wards (PTC) : a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trialSil BalarezoNoch keine Bewertungen

- NT Biology Answers Chapter 11Dokument4 SeitenNT Biology Answers Chapter 11ASADNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quality Form Oplan Kalusugan Sa Deped Accomplishment Report FormDokument11 SeitenQuality Form Oplan Kalusugan Sa Deped Accomplishment Report Formchris orlanNoch keine Bewertungen

- NeedlestickDokument14 SeitenNeedlestickluis_chubeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ketamine For Treatment-Resistant Depression (2016)Dokument167 SeitenKetamine For Treatment-Resistant Depression (2016)JorgeMM67% (3)

- 3 - PancreaseDokument12 Seiten3 - PancreasemyarjddbzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tanda, Ciri-Ciri Dan Perbedaan Versi B InggrisDokument2 SeitenTanda, Ciri-Ciri Dan Perbedaan Versi B Inggriselama natilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- B-Blood Banking History 2-4-21: RequiredDokument5 SeitenB-Blood Banking History 2-4-21: RequiredFlorenz AninoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acr 2016 Dxit Exam Sets - WebDokument129 SeitenAcr 2016 Dxit Exam Sets - WebElios NaousNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 43 - Thrombocytopenia and ThrombocytosisDokument6 SeitenChapter 43 - Thrombocytopenia and ThrombocytosisNathaniel SimNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01CLOSTRIDIUMDokument15 Seiten01CLOSTRIDIUMaldea_844577109Noch keine Bewertungen

- This Study Resource Was Shared Via: Fncp-Health Deficit: Diabetes MellitusDokument3 SeitenThis Study Resource Was Shared Via: Fncp-Health Deficit: Diabetes MellitusAlhadzra AlihNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Mechanism Isorhythmic: of Synchronization A-VDokument11 SeitenThe Mechanism Isorhythmic: of Synchronization A-VSheila AdiwinataNoch keine Bewertungen