Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

'Pressed For Time' - The Differential Impacts of A 'Time Squeeze

Hochgeladen von

Liu Yu Cheng0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

16 Ansichten25 SeitenThis paper reviews analysis of the Health and Lifestyle Survey (HALS), 1985 and 1992, in order to shed light on'senses' of time squeeze. 75% of respondents felt at least'somewhat' pressed for time, with variables of occupation, gender, age and consumption significantly increasing senses of being 'pressed for time' this is not surprising given theories of the 'time squeeze'

Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

'Pressed for Time'– the Differential Impacts of a 'Time Squeeze

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThis paper reviews analysis of the Health and Lifestyle Survey (HALS), 1985 and 1992, in order to shed light on'senses' of time squeeze. 75% of respondents felt at least'somewhat' pressed for time, with variables of occupation, gender, age and consumption significantly increasing senses of being 'pressed for time' this is not surprising given theories of the 'time squeeze'

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

16 Ansichten25 Seiten'Pressed For Time' - The Differential Impacts of A 'Time Squeeze

Hochgeladen von

Liu Yu ChengThis paper reviews analysis of the Health and Lifestyle Survey (HALS), 1985 and 1992, in order to shed light on'senses' of time squeeze. 75% of respondents felt at least'somewhat' pressed for time, with variables of occupation, gender, age and consumption significantly increasing senses of being 'pressed for time' this is not surprising given theories of the 'time squeeze'

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 25

Pressed for time the differential

impacts of a time squeeze

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

Abstract

The time squeeze is a phrase often used to describe contemporary concerns about

a shortage of time and an acceleration of the pace of daily life. This paper reviews

analysis of the Health and Lifestyle Survey (HALS), 1985 and 1992, and draws upon

in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted with twenty British suburban house-

holds, in order to shed light on senses of time squeeze. 75% of HALS respondents

felt at least somewhat pressed for time, with variables of occupation, gender, age

and consumption signicantly increasing senses of being pressed for time. This is

not surprising given theories of the time squeeze. However, identication of vari-

ables only offers insights into isolated causal effects and does little to explain how

or why so many respondents reported feeling usually pressed for time. Using inter-

view data to help interpret the HALS ndings, this paper identies three mecha-

nisms associated with the relationship between practices and time (volume,

co-ordination and allocation), suggesting that harriedness represents multiple

experiences of time (substantive, temporal dis-organisation, and temporal density).

In conclusion, it is argued that when investigating harriedness it is necessary to

recognise the different mechanisms that generate multiple experiences of time in

order for analysis to move beyond one-dimensional interpretations of the time

squeeze, and in order to account for the relationship between social practices and

their conduct within temporalities (or the rhythms of daily life).

Time, like money, has become a basic unit of measurement during modernity.

E.P. Thompson (1967) demonstrated how organising the production process

according to time-oriented action was central for the development of indus-

trial societies, while Veblens (1953: 43[1899]) account of the leisure class

where conspicuous abstention from labour . . . becomes the conventional

mark of superior pecuniary achievement highlighted how time can be asso-

ciated with social status. Yet, contemporary anxieties about time go beyond

measurement and display. Put simply, time is often viewed as being squeezed,

that people can no longer nd the time to complete the tasks and activities

most important to them and that the pace of life is increasing (Cross, 1993;

DEMOS, 1995). There are many explanations as to why this is the case. Some

explore substantive changes in the duration of time spent on particular tasks,

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd.,

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, 02148, USA.

such as paid and unpaid work (Gershuny, 2000; Schor, 1992). Others consider

the temporal organisation of societies (Zerubavel, 1979), while qualitative

accounts examine narratives and experiences of those most vulnerable to

time pressures (Hochschild, 1997; Thompson, 1996). The problem remains,

however, that little agreement can be found regarding whether experiences

of a time squeeze (or being harried) are as pervasive as popular discourse sug-

gests, what socio-structural mechanisms generate a time squeeze and whether

its effects are distributed evenly across society.

This article reviews analysis of the Health and Lifestyle Survey (HALS),

1985 and 1992, and draws upon in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted

with twenty British suburban households in order to shed light on senses of

time squeeze. The HALS is interesting because it asked respondents whether

they felt pressed for time and therefore presents a quantitative source of data

which can be associated with the notion of being harried a term often

employed by people interviewed in the qualitative part of this study.

1

Liter-

ally, the verb harried means to harass and to worry (Oxford English

Dictionary). However, since Linder (1970) appropriated the term to describe

the harried leisure class, its meaning has come to be associated more directly

with both a lack of time and the acceleration of daily life. For example, to be

harried is similar to being hurried and harassed in the sense that people hurry

to complete tasks within limited time frames or feel harassed by the burden

of obligations to others. To this, the term harried adds a degree of anxiety

regarding the temporal over-load created by the proliferation of simultane-

ous demands (Southerton, 2003).

Following a brief review of the many accounts which address why a time

squeeze may be emerging results from the HALS are presented. Accompa-

nied by analysis of interview data, these results demonstrate how occupation,

gender, age and consumption held various implications for the degrees to

which people felt harried. When the data sources are taken together three

mechanisms which generate different experiences of harriedness are

revealed. This suggests that when analysing time it is necessary to consider

how multiple inter-connected, yet relatively distinct, mechanisms are at play

in the conditioning of temporal experiences, not all of which relate to the dis-

tribution of practices in time but to the conduct and collective organisation

of practices in time (and space).

Explanations of the time squeeze

Explanations of the time squeeze, of being harried and pressed for time

can be broadly summarised within three themes of social change economic,

cultural and technological. The themes are not mutually exclusive, although

they do indicate contrasting approaches to the study of time. This review

is not exhaustive. Rather, it represents the theoretical orientation of key

accounts that address this subject of social scientic enquiry.

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

216 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

Economic change

Those who point to economic change as the root cause of a time squeeze iden-

tify mechanisms related to employment and the provisioning of goods and

services. Some highlight the pressures placed on people to work longer hours.

Two related processes are widely identied. The rst focuses on workplace

competition, employees being pitted against one-another (with respect to

career progression) in a way that generates a culture of working long hours

the principal means of demonstrating commitment and ambition by employ-

ers (Rutherford, 2001; Kunda, 2001). The second emphasises the organisation

of capitalist workplaces. Schor (1992, 1998) explains the economic benets

for rms of training a limited number of employees who work long hours as

opposed to a larger number of employees who work limited hours. She also

highlights the signicance of consumption in ratcheting upwards the hours

people spend in paid work. Assuming that people value their consumption

relative to others and that a global consumer culture places the lifestyles of

the most afuent as the key consumer referent group, then the average indi-

vidual needs to earn more money (Schor, 1998: 123). Overall, the logic of

global capitalism is that people work more to consume more. The difculty

with these arguments is that much, although not all, time use data suggests

that people are not working longer hours. Robinson and Godbeys (1997)

analysis demonstrated that Americans felt more rushed in 1995 than they did

in 1965 despite having signicantly more leisure time. Importantly, analysis of

social change is dependent on the historical time scales taken for compara-

tive analysis. Gershuny (2000) demonstrates that the general trend in the UK

is a decrease in hours worked until the mid-1980s when hours spent in paid

work increased slightly.

The changing distribution of time spent in work and leisure is important,

but says little about the temporal organisation of daily life. Garhammer

(1995), describing the shift toward post-Fordism, identies a process of ex-

ibilization whereby working times and locations are increasingly de-regulated

and scattered. The consequence is a temporal shift from 9 to 5, Monday to

Friday to the 24 hour society, from collectively maintained temporal

rhythms toward individually organised temporalities. While Breedveld (1998)

demonstrates that the 9 to 5 model remains the dominant practice in the

Netherlands, his analysis of scattered working hours does suggest that those

with higher socio-economic status are best placed to utilise exibilization and

gain greater control over their own daily use of time because they have auton-

omy over the allocation of tasks within their working day and over which

hours of the day that they work. By contrast, exibilization for lower socio-

economic status groups tends to be controlled by employers and it is this

group who suffer most from the temporal fragmentation caused by working

irregular hours. Wouters (1986) discussion of informalisation, whereby

group-based norms are eroded, also implies a reduction in the rigidity of insti-

tutionally timed events. A clear example is the growth of grazing patterns of

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 217

eating and decline of the family meal (Charles and Kerr, 1988). Taken

together, exibilization and informalisation imply a weakening of socio-tem-

poral structures that, in the absence of xed institutional temporalities, make

the potential for co-ordinating practices between social actors increasingly

problematic (Warde, 1999; Southerton et al., 2001). These are theories that

can be described as indicating a process of de-routinization of societys col-

lective temporal organisation.

A third set of theories refers to the growing number of women entering

the workforce. It is suggested that women in dual income households

experience a dual burden as a consequence of juggling both paid employ-

ment and their continued responsibility for domestic matters (Thompson,

1996). One symptom of the squeeze placed on womens time is the require-

ment to multi-task or do many tasks simultaneously in order to t them all

in to nite amounts of daily time (Sullivan, 1997). Perhaps more profound

are the implications for how people interpret and organise time in their

daily life. In her ethnographic study of a major American corporation,

Hochschild (1997) draws together accounts of how intensifying global com-

petition increases hours of paid work and the temporal implications of a dual

burden. She argues that as hours of paid work increase (what she calls

the rst shift), time for domestic matters (the second shift) become squeezed,

creating the need for a third shift whereby people attempt to create quality

time for their loved ones. This is a process of rationalisation because the

principles of Taylorization, whereby tasks are broken down into their com-

ponent parts (fragmented) and re-sequenced to maximise temporal efciency,

have become applied to domestic matters. Consequently, the second shift

becomes time pressured and, Hochschild suggests, the process spills into

the third shift where even quality time becomes regulated by the principles

of efcient time use and time itself comes to be viewed as a means to an

end.

Crucial to the dual burden thesis is the claim that women have compara-

tively less leisure time than they did in the past and than men. Bittman

and Wajcman (2000) demonstrate that in OECD countries, when taking paid

and unpaid work together, there is very little difference in the number

of minutes men and women spend in work. While undermining the dual

burden thesis, Bittman and Wajcmans study does reveal important distinc-

tions in the quality of leisure time experienced by men and women. They

distinguish between pure and interrupted leisure and show that men

enjoy more leisure time that is uninterrupted. Womens leisure, by contrast,

tends to be conducted more in the presence of children and subject to punc-

tuation by activities of unpaid work. In addition to implying that womens

leisure time maybe less restorative than mens, Bittman and Wajcman show

how the socio-economic organisation of time, particularly in terms of the

domestic division of labour, can produce qualitatively different experiences

of time.

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

218 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

Cultural change

Linder (1970) was the rst to identify cultural changes in leisure practices and

associate them with shifting cultural orientations toward time use. Turning

Veblens theory of the leisure class around, Linder argued that the relation-

ship between status and leisure today rests on the volume of leisure experi-

ences rather than on the conspicuous display of idleness. To display status

through leisure requires the consumption of more and more leisure practices,

a process which in turn renders leisure less leisurely as people attempt to cram

more activities into their daily life (Roberts, 1976). This basic argument is

taken further by Darier (1998) who suggests that being busy is symbolic of a

full and valued life. In his conceptualisation of the problem, reexive mod-

ernisation and the emerging demands on individuals to narrate their identity

through styles of consumption (see Bauman (1988) and Giddens (1991) for a

detailed exposition of this theory) brings with it the demands of trying new

and varied experiences, and it is this which leads individuals toward the in-

nite pursuit of more cultural practices. In short, being busy is now a necessary

requirement of reexive identity-formation.

Accounts of changing orientations toward consumption lend some support

to Linder and Dariers theories. Peterson and Kern (1996) discuss omnivo-

rousness an orientation toward consumption where good taste is judged less

by a depth of knowledge in specied cultural practices and more by a broad

understanding of many different genres. From a different theoretical position,

Lamont (1992) points to the orientation of the professional middle classes

toward cosmopolitanism and self-actualisation the serious and committed

pursuit of many novel cultural activities. Both accounts imply that changing

cultural orientations toward consumption make it a set of social practices both

more demanding on time use and more central to social life. It follows that

such cultural changes bring with them new experiences of time that, when

taken in conjunction with the theories of Linder and Darier, indicate that con-

sumption might be a central mechanism in generating the time squeeze.

Technological change

Accounts of socio-technological change highlight how emerging technologies

impact on the temporal organisation of society. Innovations in the form of

labour-saving domestic appliances have received most attention. The basic

conundrum is whether labour-saving technologies also save time. Vanek

(1978) demonstrated that the amount of time devoted to domestic work by

women in the USA remained constant between the 1920s and 1970s. Given

that this period featured the rise of domestic labour-saving technologies,

Vanek explains this consistency by recognising that such technologies increase

domestic productivity and with this comes a corresponding increase in (cul-

tural) standards of domestic work. In other words, labour-saving technologies

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 219

contribute to an increased frequency, range and quality of domestic work.

As Schwartz-Cowan (1983) indicates, net gains in time saving are therefore

limited while expectations of time saving are high, leaving impressions that it

is time which has become squeezed rather than that domestic technologies

have not delivered time saving (see also Shove, 2003).

Summary

Explanations of a time squeeze all take the position that contemporary life

is at least perceived as an experience of increased harriedness, even if

empirical accounts are inconsistent in their prognosis of the condition. Analy-

sis has tended to focus on the relationships between work, home and con-

sumption, with attention paid to the changing distribution of practices within

and between these spheres of daily life. Whether quantitative methods are

employed to investigate use of time or qualitative methods to explore expe-

riences of it, the problem tends to be addressed through one-dimension that

some practices take up increasingly more time to the detriment of others

(Bittman and Wajcman being the major exception). The consequences of such

changing distributions of practices in time are then associated with broader

social changes such as those outlined above.

Despite the theoretical and analytical gains presented by these approaches,

what remains unclear is how the idea of a time squeeze has come to be so

pervasive in popular discourse. Current accounts tend to identify specic

groups as being susceptible to the same one-dimensional problem through a

plethora of largely unconnected processes. For example, dual burden theories

identify women in paid labour as being the harried, while theories of con-

sumption and workplace competition tend to focus on the middle classes. This

article is less concerned with which social groups are most pressed for time

(although the identication of why different social groups might feel pressed

for time is important to the analysis). Rather, using a combination of quan-

titative and qualitative data, our concern is with understanding whether

harriedness is a uniform experience and with revealing the mechanisms

that generate such experiences. As a starting point, we examine explanations

of economic, cultural and technological change in relation to the available

variables that affected subjective statements of the degree to which

HALS respondents felt pressed for time. The article continues to reveal three

different mechanisms responsible for generating multiple experiences of

harriedness.

Pressed for time results from the Health and Lifestyle

Survey (HALS)

2

The HALS data were collected in 1984 and 1985 to form a random sample of

9003 respondents aged 18 or over and resident in private households in Great

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

220 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

Britain, and included many variables related to the areas of consumption and

lifestyles. For example, detailed data on food consumption, smoking, alcohol

consumption, hobbies, exercising, as well as socio-demographic variables

including social class, household composition, age and gender were gathered.

The respondents were traced and re-interviewed seven years later (referred

to as the follow-up survey) and almost all the original questions were

repeated. Thus we have similar data from two points in time for the

same people. However, a number of respondents from the rst wave could

not be traced or had died when the second survey took place, reducing the

size of the second wave from 9003 to 5352. This merits some caution when

analysing the second wave of the survey as we do not know what effects

this attrition of the sample may have on the results. The models use data

pooled for the two years so that time can be taken into account. Also note

that all models, with the exception of model 1, were restricted to employees

only. Attrition is controlled for in the models below by including a dummy

variable (called lost) indicating that a respondent in wave 1 was absent in

wave 2.

3

Crucially for our analysis, questions were asked about day to day habits

and use of time including a variable reecting harriedness: Indicate how well

the description Usually pressed for time ts your life. Respondents had four

options in reply not at all, somewhat, fairly well, very well. Taking these

responses as the dependent variable in ordered logistic regression models, we

analyse the extent that people reported feeling pressed for time in terms of

social class, age, gender, life-course, and consumption orientations. We were

also able to analyse the data in relation to a number of less commonly used

variables, such as the effect of shift work and going out to meet people, in an

attempt to isolate possible causes of being pressed for time. These variables

are described in table 1.

Interpretation of the survey results was aided by qualitative interview data

conducted in 2000. Twenty suburban households were interviewed regarding

their impressions of whether people are increasingly squeezed for time. The

sample comprised single households, couples with and without children and

respondents age varied between 25 and 65. Some were dual income house-

holds, some professionals and some retired, thus providing a range of demo-

graphic and socio-economic status groups. Interviewees were contacted via

letters sent to every other house in the most and least expensive areas of the

town.

4

Interviews lasted, on average, two hours. Adopting a conversational

approach (Douglas, 1985) toward semi-structured interviews, interviewees

were asked about whether society was, in general, more time pressured than

in the past, whether they felt pressed for time, to recount and reect on the

previous week and weekend day, and to recall moments when they felt

harried. In this article, interview data is used to illustrate and help interpret

the signicance of the HALS results (for a more detailed analysis of the qual-

itative data see Southerton, 2003). What follows is a general description of the

survey ndings, starting with responses to the initial question and followed by

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 221

regression analysis of how occupation, age, gender, life-course and consump-

tion affected the degree to which people felt pressed for time.

How many people are pressed for time?

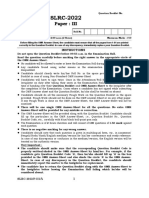

Figure 1 reveals that little change has taken place between 1985 and 1992 with

regards to feeling pressed for time. This is perhaps not surprising given the

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

222 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

Table 1 Complete list of independent variables included in the models

Variable name Description

y92 Dummy: 1 if year = 1992, 0 if year = 1985

lost Attrition dummy set to 1 if no response in second wave

i Occupation professional (RG I)

ii Occupation manager (RG II)

iiin Occupation routine non manual (RG IIIN)

iiim Occupation skilled manual (RG IIIM)

iv Occupation semi skilled (RG IV)

6

unemp Unemployed

sickdis Sick or disabled

retired Retired

student Full time student

hwife Full time housewife

thirties Aged 3039

forties Aged 4049

fties Aged 5059

sixties Aged 60 and above

7

female Female

wk1120 Hours worked 1120

wk2130 Hours worked 2130

wk3140 Hours worked 3140

wk4198 Hours worked 41 or more

8

drive2-drive4 Indicators of drive and ambition from a 4 point scale (base 1 is

lowest)

shift Whether has shift work

super Whether supervises others

/mi etc. Occupation interacted with gender (e.g., = female class I,

miv = male class IV etc.)

kids04m Man with children aged 04

kids04f Woman with children aged 04

kids511m Man with children aged 511

kids511f Woman with children aged 511

logomni Omnivorousness score

gooutlot Indicator of people who go out a lot

seeppl Indicator of people who go out to see people a lot

spur People who indicate they do things on the spur of the moment

carefree People who describe themselves as carefree

relatively short time scale between the two sample years, and because expla-

nations of an increasing sense of feeling harried tie the process to a broader

time frame. Figure 1 suggests that three quarters of the population report

feeling at least somewhat pressed for time but whether somewhat pressed for

time constitutes being harried is open to interpretation.

Impact of employment status and occupation on harriedness

Initial regression results

5

(see table 2) show that all classes are more pressed

for time relative to classes IV and V (note that the non-employed are not

assigned to a class in this analysis). The professional and managerial groups

reported being most pressed for time and non-employed groups, other than

housewives, were signicantly less pressed for time than those in work. Thus,

the unemployed, students, the sick and disabled, and the retired are all less

pressed for time. There is a marginal decline in being pressed for time in 1992,

but this is only just signicant at the 5% level. More importantly the attrition

indicator appears to be insignicant so we can be more condent that attri-

tion in the second wave is not having a dramatic effect on the results. Other

signicant effects from the rst model show highly signicant age effects with

time pressure declining as respondents get into their fties and beyond, and

a highly signicant gender effect with women much more likely to describe

themselves as pressed for time than men.

The class effect persists even when we control for number of hours

worked among employees in the sample (table 3), but only for managerial

and professional workers. Thus among the employed the most harried seem

to be at the upper end of the white-collar spectrum. When we only consider

employees there is no signicant change in harriedness over time (y92 is

insignicant) and again the attrition indicator is insignicant. It may be the

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 223

Indicate how well the description Usually

pressed for time fits your life (%)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Not at all Somewhat Fairly well Very well

Year

1985

1992

Figure 1 degrees of feeling pressed for time in 1985 and 1992

case that some generalisable characteristics of professional and managerial

jobs make them more demanding in terms of time. This argument gains

support when the variable pressed for time is analysed in relation to whether

people work shifts or whether they supervise others. Table 4 demonstrates that

supervisory roles, which require a degree of responsibility for the time man-

agement of others, and not working xed hours (i.e. not working to a shift

system) increases senses of being pressed for time. This provides some support

for Garhammers theory of the impacts of exible work and Breedvelds

claims to a process of de-routinization, whereby an erosion of structured work

times makes collective action a case of individual time management and has

the effect of intensifying the immediacy of time. However, the class effect

remains even when these things are taken into account.

Explanation as to why being professional middle class served as a signi-

cant variable might be found by generalizing about the workplace and social

status. Rutherford (2001) and Kundas (2001) ethnographic accounts of time

and professional occupations suggest that the corporate world encourages,

if not demands, high degrees of employee competition as an incentive for

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

224 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

Table 2 A basic model with occupation, age and gender all respondents

Number of obs = 10,356

Ordered Logit Estimates chi2(17) = 1,664.76

Log Likelihood = -13,239.853 Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

Variable Coef. Std. Err. P > |z| Pseudo R2 = 0.0592

y92 -0.0933702 0.0471658 0.048

lost -0.0722766 0.0489713 0.140

i 0.8874785 0.1176081 0.000

ii 0.867675 0.090162 0.000

iiin 0.4642229 0.0993753 0.000

iiim 0.415411 0.0884631 0.000

iv 0.1567807 0.0997465 0.116

unemp -0.5803457 0.126371 0.000

sickdis -1.065291 0.1816903 0.000

retired -0.8239733 0.1149354 0.000

student -0.4924166 0.112017 0.000

hwife -0.1459078 0.1016325 0.151

thirties 0.0557434 0.0599808 0.353

forties -0.0877262 0.0620595 0.157

fties -0.2478916 0.0646654 0.000

sixties -0.555723 0.0830194 0.000

female 0.3291287 0.0386622 0.000

_cut1 -1.156138 0.0981035 (Ancillary parameters)

_cut2 0.4564696 0.0972167

_cut3 1.812553 0.0992585

ambitious employees. Apart from placing pressure on employees to work

longer hours, workplace competition has the effect of intensifying work rates,

meaning that even those who did not work long hours still felt the impact of

time pressure. This was also an explanation offered by interviewees such as

Suzanne:

in the seventies stress wasnt a word was it? . . . in the commercial world,

and you know a lot more is expected of you compared to that era . . . I think

companies . . . they demand blood . . . that makes it very competitive . . . The

knock on effect of that then when youre looking at your personal life and

that sort of thing, then you havent got time! Because youre directing all your

time in trying to be successful in your career.

Rutherford and Kundas studies also indicate how being harried has become

an important part of professional middle class identity and source of social

status. Take for example Stevens remarks about career success:

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 225

Table 3 Effects of hours worked employees only

Number of obs = 5,908

Ordered Logit Estimates chi2(16) = 399.59

Log Likelihood = -7,675.1401 Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

Variable Coef. Std. Err. P > |z| Pseudo R2 = 0.0254

y92 -0.0597711 0.0534919 0.264

lost -0.020583 0.0666777 0.758

i 0.6927484 0.1498345 0.000

ii 0.5871587 0.1294274 0.000

iiin 0.2377826 0.1364008 0.081

iiim 0.1634402 0.1278771 0.201

iv -0.1139742 0.1365585 0.404

thirties 0.1311829 0.0726211 0.071

forties -0.0261868 0.073514 0.722

fties -0.1653488 0.0795361 0.038

sixties -0.30182 0.1124572 0.007

female 0.6749304 0.0579366 0.000

wk1120 0.3600338 0.1159055 0.002

wk2130 0.5460537 0.1197813 0.000

wk3140 0.4706091 0.1042179 0.000

wk4198 1.143891 0.1125365 0.000

_cut1 -0.7232272 0.1689376 (Ancillary parameters)

_cut2 1.148328 0.1686873

_cut3 2.509649 0.171139

if youre successful or have a high status job then youll be busy and not

have enough time for yourself because youll have so much to do. Its the old

money rich time poor syndrome.

To not identify oneself as harried within the context of dynamic careers was

tantamount to admitting that one did not belong to the successful professional

middle classes and was lacking ambition and personal determination to

succeed within that environment.

HALS does not contain variables of workplace competition to allow for

direct testing of this hypothesis. However, it does ask questions regarding the

degree to which respondents felt they were ambitious. As Table 4 indicates,

ambition was related to an increased likelihood of reporting being pressed

for time. Whether being ambitious is a personal characteristic particular to

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

226 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

Table 4 Models including other work oriented variables employees only

Number of obs = 5,908

Ordered Logit Estimates chi2(21) = 772.83

Log Likelihood = -7,488.5195 Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

Variable Coef. Std. Err. P > |z| Pseudo R2 = 0.0491

y92 -0.0569811 0.0538156 0.290

lost -0.057432 0.0671888 0.393

i 0.4985009 0.1529758 0.001

ii 0.395934 0.131889 0.003

iiin 0.1141724 0.1377934 0.407

iiim 0.0856758 0.1290255 0.507

iv -0.1271915 0.1376565 0.355

thirties 0.2184767 0.0735777 0.003

forties 0.1059875 0.0748754 0.157

fties -0.0360448 0.0808012 0.656

sixties -0.2352873 0.1131939 0.038

female 0.8265935 0.0594302 0.000

wk1120 0.3749939 0.1167885 0.001

wk2130 0.5269522 0.1208173 0.000

wk3140 0.3561772 0.1066145 0.001

wk4198 0.9243931 0.1156808 0.000

drive2 0.5584821 0.0817706 0.000

drive3 0.8648146 0.0812849 0.000

drive4 1.70397 0.100324 0.000

shift_ -0.267912 0.0715689 0.000

super_ 0.1935124 0.0548396 0.000

_cut1 -0.0465987 0.1805062 (Ancillary parameters)

_cut2 1.894702 0.1817661

_cut3 3.325726 0.1851352

the professional middle classes or an outcome of increased workplace com-

petition in professional occupations is a debate beyond the scope of this

article. At the very least it seems that being harried has become intimately

connected with being a member of the professional middle classes in addition

to any personal ambitions they might have.

The effects of gender

We saw in table 2 that gender was highly signicant. Table 5 demonstrates that

women in the same occupations as men generally reported feeling more

pressed for time. Professional and managerial women reported feeling the

most pressed for time of all female employees and more so than their male

counterparts. This nding is consistent with the effects of workplace compe-

tition having a greater effect on women compared with men in the same occu-

pation (Rutherford, 2001). However, the largest gap between men and women

of the same occupation can be found in the intermediate classes occupations

less readily associated with workplace competition over career progression.

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 227

Table 5 Gender and occupational interaction effects employees only

Number of obs = 5,961

Ordered Logit Estimates chi2(16) = 235.99

Log Likelihood = -7,828.0971 Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

Variable Coef. Std. Err. P > |z| Pseudo R2 = 0.0148

y92 -0.032267 0.0531224 0.544

lost 0.0102972 0.0658993 0.876

0.8131743 0.1726698 0.000

mi 0.6115915 0.1652358 0.000

i 0.8290091 0.1309003 0.000

mii 0.5620387 0.1297832 0.000

iin 0.4947467 0.140924 0.000

miiin 0.0960335 0.1467161 0.513

iim 0.419361 0.1289212 0.001

miiim 0.0475298 0.1271188 0.708

v 0.2330796 0.1427538 0.103

miv -0.3380453 0.1472103 0.022

thirties 0.1281205 0.0712439 0.072

forties -0.0012553 0.072553 0.986

fties -0.1545216 0.0783178 0.048

sixties -0.4321708 0.1096457 0.000

_cut1 -1.567225 0.1308244 (Ancillary parameters)

_cut2 0.2737908 0.1284503

_cut3 1.604649 0.130285

The gap between men and women appears only partially attributable to dif-

ferential pressures in the workplace.

It is interesting to note that Bittman and Wajcmans (2000) time use study

reports the total paid and unpaid working hours of men and women for the

UK in 1985 (the same year as the rst wave of the HALS). Using this data,

we can see that UK men and women worked approximately 47 hours each

per week. However, women were responsible for 76% of total time spent in

unpaid work. Taken together with the HALS results it appears that women

report feeling pressed for time more than men regardless of occupation and

despite similar total hours of paid and unpaid work. This lends some support

to the dual burden theory as explained by Thompson (1996). It implies that

the dual burden is less about total hours worked and more about the respon-

sibilities and obligations that accompany unpaid work and particularly the

work of caring for children. Thompson (1996) employs the metaphor of jug-

gling to capture working mothers experience of time and the personal anx-

ieties that arise through managing motherhood and career. Yet surprisingly,

table 6 demonstrates that having very young children (under 5) had little

bearing on the degree to which women felt pressed for time when compared

to men. Indeed it appears to be men with small children rather than women

that are the more pressed for time, all things considered. The survey

data, therefore, either indicates that dual burden theories are mistaken in their

prognosis that juggling paid work and caring for the family create senses

of harriedness or that the survey question fails to capture particular experi-

ences of time that might otherwise be described as harried. Both men and

women with children aged 511 showed a marginal effect on being presses for

time.

Interviews with women did indicate that having young children signicantly

increased senses of being harried even if those women did not describe them-

selves as lacking time. Cindy provided a good case in point. She described

use of time during the day of interview as a mix between leisure and domes-

tic tasks:

I worked out in the gym . . . Then I came home, had my lunch and pottered

around the house for a bit which is quite unusual for me because I usually

tend to go to the shops or see friends or whatever . . . I had to be back to the

school for about three . . . Then we walk home from school and I spent a

whole hour getting her [daughter] to eat her tea ready for gym club which

was quarter to ve.

Given this description of events it was not surprising that Cindy suggests she

is not short of time. However, she was clear that she was sometimes harried:

I nd the mornings very very hectic what with trying to feed her, get her

dressed, to get myself dressed and get her out the door in time to get her to

school. Like this evening she got back from school, we had about one hour

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

228 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

and then she had to go to gym club and I was like, thats not enough time,

she needs to eat her tea and you would think an hour is plenty but, so I nd

myself stressed all the time by trying to get her to places for the time she needs

to be there.

What is important about Cindys case is that she demonstrates how being

harried should not be conated with feeling pressed for time because

harried is a term which describes a density of social practices within specic

frames of time. Pressed for time, by contrast, implies a general shortage of

free time.

Of course, one reason why working mothers may not have reported addi-

tional degrees of feeling pressed for time is that they are more likely to have

some form of childcare. Dual burden theories suggest that women maintain

responsibility for the organisation and transportation of children to the

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 229

Table 6 Impact of children employees only

Number of obs = 5,961

Ordered Logit Estimates chi2(20) = 257.76

Log Likelihood = -7,817.2155 Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

Variable Coef. Std. Err. P > |z| Pseudo R2 = 0.0162

y92 -0.0340488 0.0531607 0.522

lost 0.0163995 0.0659705 0.804

0.8213948 0.1736224 0.000

mi 0.5955452 0.1657334 0.000

i 0.8481595 0.1318441 0.000

mii 0.5472701 0.1305113 0.000

iin 0.5244022 0.1416063 0.000

miiin 0.098522 0.1471445 0.503

iim 0.4371475 0.1299953 0.001

miiim 0.0322492 0.1278308 0.801

v 0.2543633 0.1435184 0.076

miv -0.3556183 0.1478064 0.016

thirties 0.0399756 0.0756705 0.597

forties 0.012943 0.0739842 0.861

fties -0.0979907 0.079697 0.219

sixties -0.3685517 0.1107295 0.001

kids04m 0.2378405 0.0683029 0.000

kids04f 0.1071713 0.0992041 0.280

kids511m 0.1088399 0.052991 0.040

kids511f 0.1254814 0.0542904 0.021

_cut1 -1.507913 0.1317126 (Ancillary parameters)

_cut2 0.3369538 0.1294723

_cut3 1.671726 0.1314261

various forms of day care available to them. Sarah served as a good example.

As a single working mother, Sarah admitted she was fortunate to be able to

afford a nanny to care for her two children during the daytime. She was also

adamant that Im not pushed for time because Im organised. However, she

did admit that predictable moments of her daily schedule were harried:

it is a case of getting up, feeding the two boys, making their breakfasts,

getting them off to school . . . we have this set routine, they get up, we have

our breakfast, we hoover, they have a bath, I get them dressed and then we

are ready for school. The latest that I can go upstairs for that bath is 8 oclock.

Otherwise, we are very pressured for time and then we are rushing.

Cindy and Sarah captured how mothers in the interview sample experi-

enced time, whether working mothers or not. These narrative accounts also

tally with the qualitative accounts of Hochschild (1997) and Thompson (1996)

and together indicate that the limitations of the survey question (are you

usually pressed for time) for revealing experiences of time and highlight that

a dual burden refers more to the quality of time than to the quantities of

time spent in paid and/or unpaid work.

Consumption and lifestyle

We saw in tables 2 and 3 (above) that increasing age generally has a negative

impact on being pressed for time. Life-course effects could explain why

younger adults felt more pressed than those aged over fty. However, it seems

unlikely that starting a family is signicant given the limited effect that having

young children had on women although the strong signicance for men sug-

gests that life-course is an important factor for them. Orientations toward con-

sumption offer a different account of the relationship between age and feeling

pressed for time. Schors theory that consumer culture generates the time

squeeze implies a generational effect. Consumer culture is a process that can

broadly be traced to the 1960s (Harvey et al., 2001), making those aged in

their forties and under more susceptible to the inuence of this process. To

examine this claim, it is necessary to consider the impacts of consumption and

lifestyle on survey responses.

While the Health and Lifestyle survey holds no data on the volume of time

respondents devoted to practices of consumption, it does contain variables

related to leisure activities. This allows for analysis of omnivorousness a

concept that suggests an orientation toward consumption where individuals

consume a wide variety of cultural pursuits but do not necessarily devote sig-

nicant volumes of time or energy to them. Using a measure derived from

Warde et al. (2000), where participation in various activities is combined into

a score, we were able to construct a variable to measure omnivorousness.

Table 7 shows that omnivorousness had a signicant impact on degrees of

feeling harried. Despite being unable to measure the frequency that cultural

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

230 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

activities occurred for each individual, the signicance of omnivorousness

does suggest that it may be the range of consumption interests rather than the

amount of time spent on consumption in total which increases senses of

feeling pressed for time. Indications of why this might be the case can be found

in variables regarding sociability. As Table 7 also shows, going out, in itself,

makes little difference to feeling pressed for time but going out to see people

does. It follows that the task of co-ordinating with others and with having tem-

poral deadlines for meeting others enhances senses of being pressed for time.

This was a point made by many interviewees:

Our problem is that when we arrange to go out you can guarantee that what-

ever time we need to leave by Karen will not be ready and that makes things

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 231

Table 7 effects of lifestyle all respondents

Number of obs = 10,356

Ordered logit estimates LR chi2(22) = 1,873.77

Log likelihood = -13,135.345 Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

Variable Coef. Std. Err. P > |z| Pseudo R2 = 0.0666

yr92 -0.1470373 0.0477677 0.002

lost -0.0646442 0.0491892 0.189

i 0.7817256 0.118458 0.000

ii 0.7969043 0.0907899 0.000

iiin 0.3902125 0.0999473 0.000

iiim 0.3850488 0.0886054 0.000

iv 0.1338496 0.0999785 0.181

unemp -0.6223712 0.1267945 0.000

sickdis -1.05596 0.1828032 0.000

retired -0.8418699 0.1153555 0.000

student -0.544319 0.1124722 0.000

hwife -0.1582944 0.1016999 0.120

thirties 0.1043857 0.060403 0.084

forties 0.0003151 0.062969 0.996

fties -0.1311548 0.0659491 0.047

sixties -0.4178277 0.0844001 0.000

female 0.2949099 0.0390883 0.000

logomni 0.2533645 0.0326249 0.000

gooutlot 0.0456961 0.0388151 0.239

seeppl 0.1495254 0.0398839 0.000

spur 0.2468636 0.0371008 0.000

carefree -0.370981 0.0393145 0.000

_cut1 -0.8616358 0.113354 (Ancillary parameters)

_cut2 0.7735507 0.1130085

_cut3 2.1467 0.115055

difcult because we are late and then we have to try and make up time to get

there on time and its not really a very good start to an evening out. (Steven)

its okay if youre going out alone or down the pub but if youre going to

the cinema and youre late and youve arranged to meet friends then you do

rush more because of the thought of them sitting around waiting for you

(Kathryn)

Hypothetically, being omnivorous is likely to increase the range of people with

whom sociability occurs by arrangement because it will potentially expand

social networks, and together this might further exacerbate senses of being

pressed for time. More prosaically, consumption and sociability have direct

implications for how time is experienced, although the survey data is not

extensive enough to conclusively tie this either to Schors (1992) work-spend

cycle nor Linders harried leisure class.

Mechanisms generating harriedness: substantive overload,

disorganised rhythms and temporal density

The survey data is instructive in identifying variables that effected senses of

feeling pressed for time and for highlighting which social groups felt rela-

tively more pressed than others. However, isolating variables and compar-

ing groups tells us little about the mechanisms that make harriedness appear

so widespread. While analysis in relation to interview data and other empiri-

cal accounts helps interpretation of why specic variables might affect expe-

riences of time, these accounts remain fragmented and connections between

variables remain inadequately explained. Identifying the mechanisms that

generate senses of being harried is, therefore, necessary if analysis is to move

beyond a description of the problem and towards an explanation of processes.

As it stands, the survey only tests isolated causal models of why occupation,

gender, age and consumption were signicant.

Three mechanisms can be isolated from the data to explain senses of feeling

pressed for time. First is the volume of time required to complete sets of tasks

regarded as necessary, and refers to the changing distribution of practices in

time. This is a straightforward process identied in rational action theories of

time use (Becker, 1965) where, for example, working long hours reduces the

amount of time available to spend on other sets of tasks, such as domestic

work, time with family and friends, consumption and leisure. This raises issues

of what constitutes need and whether some groups are pressed for time

because they place greater value on certain practices that other groups regard

as less necessary. For example, some professionals might work longer hours

in order to gain advantage over others in the advancement of their career, or

younger people might work longer hours in order to consume more, or spend

more time devoted to consumption because it is regarded as a need rather

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

232 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

than a want. Regardless, volume of time devoted to work and/or consump-

tion practices is one mechanism that increased senses of harriedness.

The second mechanism is co-ordination, which refers to the difculties of

co-ordinating social practices with others in a society where collectively organ-

ised temporalities have been eroded. In a similar sense to the process of ex-

ibilization discussed by Garhammer and Breedvelds de-routinization, this

mechanism points to the challenges of co-ordinating collective social practices

in circumstances where institutionally derived and relatively stable temporal

rhythms are undermined by the individualised scheduling of practices. The

impact of exible working hours on degrees of feeling pressed for time serves

as a good example of this process. Omnivorous orientations toward con-

sumption are also associated with the mechanisms of co-ordination. This is

because practices of consumption often involve interaction within social net-

works (Warde and Tampubolon, 2002), and accounts of network formation

suggest that individuals develop network ties based around specic cultural

practices (Bellah et al., 1985; Fischer, 1982). Consequently, those who are

more omnivorous in their consumption orientations are likely to have a

greater range of networks in which issues of co-ordination will be central to

the organisation of those consumption practices. Allan (1989) demonstrates

that, when socialising, the working classes use public spaces where there is a

strong likelihood of meeting network members by chance rather than arrange-

ment. For the middle classes, such network meetings are pre-arranged. In both

cases, co-ordination becomes increasingly problematic in circumstances where

collective temporalities are eroded. It means that turning up in public spaces

is less likely to reveal known others because networks might, for example,

work at different times of the day, thus undermining normative meeting times.

In terms of meeting by arrangement, increasing fragmentation of collective

temporal rhythms is likely to make common agreement on suitable times to

meet more difcult. In this way, co-ordination is a mechanism which explains

why exible working hours, omnivorousness and socialising with others were

signicant variables that increased senses of feeling pressed for time.

The third mechanism refers to the allocation of practices within time.

Rather than suggest actual increases in volume of practices, allocation refers

to certain practices being located within temporal rhythms that create a sense

of intensity in the conduct of those practices. Allocation is not a mechanism

revealed by the survey data and this is important because it indicates how

experiences of time can be evaluated according to multiple criteria. For

example, narratives of juggling practices and multi-tasking that are found in

accounts of the lives of working women (Hochschild, 1997; Sullivan, 1997;

Thompson, 1996) all concern the challenges of allocating practices within par-

ticular parts of the day. Allocation is also linked to a notion of the boundaries

that separate practices. Hochschilds account of domestic work suggests that

what were once task-oriented practices have now become time-oriented,

meaning that the boundaries between domestic tasks are no longer driven by

completion of those tasks in a sequential manner but according to principles

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 233

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

234 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

of time-related efciency. Consequently, the boundaries between tasks are

eroded in the course of generating more efcient means of completing those

tasks (see also OMalley, 1992). Importantly, the allocation of practices, which

no longer have clearly dened boundaries, into particular parts of the day can

generate senses of being harried, irrespective of whether the bulk of that day

is experienced as being pressed for time. This mechanism is not restricted to

the home and can also be found in work-place practices where the allocation

of tasks is subject to personal management and where multiple tasks are con-

ducted simultaneously.

Isolating these three mechanisms reveals that harriedness is not a one-

dimensional experience. Indeed, the three mechanisms seem to generate three

distinct senses of harriedness. The mechanism of volume can be held as the

basis for substantive senses of being harried. Bradley summarised what being

substantively harried means:

between my working 5 days a week and then taking Alex [his daughter]

places at the weekend and then in the summer you have to come home and

cut the grass every week and you just have, the household management is

just like almost a day gone . . . But most of the time I leave for work at 7, get

home about 6, 6.30, do household management, sit down at 10 and if Ive

got the energy read for 20 minutes.

A second form of harriedness refers to temporal dis-organisation and is the

outcome of the mechanism of co-ordination. This sense of harriedness is less

conspicuous than the substantive form because it accounts for experiences

that are not obviously connected with an absolute shortage of time. Tempo-

ral dis-organisation takes many forms. For example, Charlotte described being

rushed:

This morning was typical, rst Mike rushes about to get out the door by

quarter to seven, then I get the girls up, dash about getting them ready and

then myself. Then its out the door, rush to school and I have to drop them

at ten to nine or I am late for work. I do my cleaning [paid work] and get

home about two, have something to eat and then get the girls from school

and generally from then on its plain sailing.

Senses of rush always related to the difculty of meeting co-ordination points

within the day, such as to collect children from school or meet with friends or

work colleagues. As Charlotte illustrated, this was caused by the problem of

co-ordinating between her personal schedule and the schedule of her daugh-

ter. However, dis-organisation was also expressed in terms of an inability to

competently organise ones own time. As Cindy explained:

I do nd that I get easily distracted, you know going to the school in the

morning, and its like Ive got to come back and I must do this and I must

do that. At the school Ill chat to friends, chat, chat, chat, chat, chat, chat,

chat, and then its oh no, come back, oh no, I was gonna do that at that

time you know.

In other cases, temporal dis-organisation was presented as the outcome of

obligations to others:

because he [his brother] works typical hours he thinks I can meet up for a

drink at 5. If I dont he thinks Im avoiding him, that my jobs more impor-

tant than he is . . . So I will try and meet up and I either rush everything to

get it nished before I leave or know its waiting for me the next morning.

(Ashley)

Ashley, who worked exible hours, neatly illustrates the difculty of aligning

personal schedules in conditions where others work xed (shift) hours. It also

illustrates how senses of harriedness were exacerbated by senses of obligation

to overcome temporal dis-organisation and create time for signicant others.

Normative expectations surrounding obligation was also found in statements

such as quality time, chill time and bonding time.

Finally, density of practices allocated within time frames acts as a third

sense of harriedness. Temporal density accounts for experiences of time that

can be described as juggling and multi-tasking. As Sarah and Cindy illus-

trated when describing their day, it suggests an uneven experience of tempo-

ralities in which parts of the day are packed with activities while other parts

are relatively empty. Take Chloes description of times when she felt harried:

Some mornings are chaos, after getting them off to school Ill have a cup of

tea and a sit down, then Ill try and get all the housework done so that I can

get off to work for 12.00 and thats as busy as getting the kids off, you know,

start the washing, do some ironing, make the beds, then the washing nishes,

so I stop what Im doing and peg it out . . . Work is easy, the most relaxing

part of the day because I only have to do one thing . . . Tuesdays and Thurs-

days are not so bad because I dont do housework, Ill meet friends or go

swimming or shopping.

For Chloe, temporal dis-organisation is apparent in that she rushes to meet

an institutionally dened meeting point (school), but the multi-tasking of

housework is equally an experience of harried because of the density of tasks.

However, when asked if she felt generally pushed for time she answered: no,

Im busy some of the time but not others. This helps explain why having small

children did not necessarily register as signicant in relation to reporting

feeling usually pressed for time in the survey. Interviewees such as Sarah,

Cindy and Chloe did describe being harried but were always quick to point

out the partiality of that experience, and in doing so avoided describing the

emotional work of childcare as being substantively harried.

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 235

Isolating mechanisms that explain why people might feel harried or pressed

for time and distinguishing between different forms of harriedness is instruc-

tive in accounting for multiple experiences of time. It suggests that when

analysing time it is important to account for the mechanisms that impact on

experiences of time, recognising that different methodological approaches

offer insights into particular experiences. In this case, the survey data gener-

ated understandings of the factors that led to outcomes of being pressed for

time while qualitative data shed light on the mechanisms that generated mul-

tiple experiences of being harried. Moreover, while scope for analysing which

mechanisms and forms of harriedness were most applicable to specied

social groups was beyond the scope of this article, the identication of multi-

ple experiences does offer a framework for exploring the (changing) socio-

structural circumstances that lead to particular senses and experiences of the

time squeeze.

Conclusion

Approaches to the analysis of a time squeeze tend to account for experi-

ences of time through one-dimensional processes that explore the changing

distribution of time spent on certain practices to the detriment of others. This

has produced valuable insights into changing time use and provided indica-

tions as to why particular social groups might feel increasingly harried.

However, such accounts are limited in their capacity to either generalise their

ndings beyond specic groups or to provide sufciently nuanced accounts of

differential experiences of time. Consequently, while insight is gained into

many social changes that might generate substantive shifts in the distribution

of practices within time for many social groups, little progress has been made

in the identication of key mechanisms that generate senses of harriedness

nor of distinguishing between different senses of being harried.

Analysis of the HALS data and in-depth household interviews offered the

opportunity to bring together the many theoretical and empirical accounts of

the time squeeze and to reveal underlying mechanisms that effect multiple

experiences of harriedness. Occupation in relation to the number of hours

worked, whether respondents worked exible hours, supervised others and

degree of ambition all had signicant independent effects on degrees of

feeling pressed for time. Socio-economic status was also important, as was

gender, age, consumption orientations, and socialising with others. The mech-

anisms which contributed towards how and why these variables impacted on

senses of being harried all related to the organisation of personal and collec-

tive social practices within time and according to the temporalities of every-

day life. Consequently, the volume, co-ordination and allocation of social

practices were the key mechanisms that generated harriedness and each

mechanism was associated with different experiences of time. This demon-

strates that when investigating the time squeeze it is important not to con-

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

236 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

ate experiences related to being pressed for time to factors concerning only

lack of time for the conduct of particular activities (such as domestic work

or sociability with friends and family).

By identifying different mechanisms that generate, and different forms of,

harriedness, this research also suggests a framework for future investigations

of the time squeeze. Of particular importance is analysis of which forms of

harriedness are most closely associated with specic social groups, and under

what conditions are the mechanisms that generate harriedness produced (for

example, is the mechanism of allocation most pertinent to housewives or does

it also have general currency in, say, the workplace). Further understanding

of the mechanisms of co-ordination and allocation is also required, and analy-

sis of the organisation or sequencing of practices is one potentially instructive

approach. This would not only provide insights into how temporalities, or the

rhythms of daily life, are changing, but also further demonstrate how it is the

relationship between the conduct (and particularly the temporal challenges

of collective conduct) of different types of practices (rather than increases of

time spent on one set of practices at the expense of another) that is crucial in

accounting for the signicance of these two mechanisms in contemporary

experiences of time.

Notes

1 Many time use diary surveys contain a survey component that enquire into subjective experi-

ences of being time pressured. HALS data is not superior in quality to these other data sets

but is longitudinal and therefore allows for pooled analysis of two points in historical time.

2 Data were supplied by the Data Archive, Colchester, Essex and the interpretation of the data

is solely our responsibility.

3 The pooling of the cases means that the 1992 responses are all 7 years older than the 1985, and

since there is no replacement of cases this means that there are a lot fewer respondents in their

twenties in 1992 and a lot more aged over 59. As a result, and given that over 59 year olds

reported feeling less time pressured, it is likely that the marginal decline in overall senses of

feeling pressed for time is a consequence of the panel survey sample. Secondly, further analy-

sis that uses the panel, rather than pooled, data is possible. This would allow us to answer ques-

tions such as whether changed individual circumstances over the seven year period lead to

changes in degrees of feeling pressed for time. While these is not scope within this article to

consider panel data analysis, such an approach would provide an opportunity to model changes

in harriedness in terms of the mechanisms that generate harriedness as identied by pooled

data.

4 The term respondent refers to those responses from the HALS data, interviewee for those

from the qualitative interviews.

5 One may interpret these coefcients as one would interpret binary logistic regression coef-

cients except here the dependent variable has more than two values. In other words a positive

coefcient indicates an increased chance that a subject with a higher score on the independent

variable will be observed in a higher category of being pressed for time. A negative coefcient

indicates that the chances that a subject with a higher score on the independent variable will

be observed in a lower category of being pressed for time.

6 Base class is class V (unskilled).

7 Base age is under 30.

8 Base hours worked is less than 10.

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 237

References

Allan, G., (1989), Friendship: Developing a Sociological Perspective, London: Harvester

Wheatsheaf.

Bauman, Z., (1988), Freedom, Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Becker, G., (1965), Theory of the Allocation of Time. Economic Journal, September, pp. 493517.

Bellah, R., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W., Swindler, A. and Tipton, S., (1985), Habits of the Heart:

Individualism and Commitment in American Life, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bittman, M. and Wajcman, J., (2000), The Rush Hour: the character of leisure time and gender

equity, Social Forces, 79 (1): 165189.

Breedveld, K., (1998), The Double Myth of Flexibilization: trends in scattered work hours, and

differences in time sovereignty, Time & Society, 7 (1): 129143.

Charles, N. and Kerr, M., (1988), Women, Food and Families, Manchester: Routledge.

Cross, G., (1993), Time and Money The Making of Consumer Culture, London: Routledge.

Darier, E., (1998), Time to be Lazy. Work, the environment and subjectivities, Time & Society,

7 (2): 193208.

DEMOS, (1995), The Time Squeeze, London: Demos.

Douglas, D., (1985), Creative Interviewing, Sage: London.

Fischer, C., (1982), To Dwell Among Friends: Personal Networks in Town and City, Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Garhammer, M., (1995), Changes in Working Hours in Germany, Time & Society, 4 (2): 167203.

Gershuny, J., (1992), Changes in the domestic division of labour in the UK, 197587: dependent

labour versus adaptive partnership, in Abercrombie, N. and Warde, A. (eds), Social Change in

Contemporary Britain, Cambridge: Polity, 7094.

Gershuny, J., (2000), Changing Times: work and leisure in postindustrial society, Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Giddens, A., (1991), Modernity and Self-Identity, Cambridge: Polity.

Harvey, M., McMeekin, A., Randles, S., Southerton, D., Tether, B. and Warde, A., (2001), Between

demand & consumption: a framework for research, CRIC Discussion Paper No 40, The Uni-

versity of Manchester and UMIST.

Hochschild, A.R., (1997), The Time Bind: when home becomes work and work becomes home,

CA Henry Holt.

Kunda, I., (2001), Scenes from a Marriage: Work, Family and Time in Corporate Drama, paper

presented to the International Conference on Spacing and Timing, November, Palermo, Italy.

Lamont, M., (1992), Money, Morals & Manners: the Culture of the French and American Upper-

Middle Class, London: Chicago Press.

Linder, S.B., (1970), The Harried Leisure Class, Columbia University Press.

OMalley, M., (1992), Time, Work and Task orientation: A critique of American Historiography,

Time and Society, 1 (3): 34158.

Roberts, K., (1976), The Time Famine, in Parker, S., (ed.), The Sociology of Leisure, Allen &

Unwin.

Robinson, J. and Godbey, G., (1997), Time for Life: the surprising ways that Americans use their

time, Pennsylvania State Press.

Rutherford, S., (2001), Are You Going Home Already?: the long hours culture, women managers

and patriarchal closure, Time and Society, 10 (2/3): 259276.

Peterson, R. and Kern, R., (1996), Changing high brow taste: From snob to omnivore and univore,

Poetics, 21: 24358.

Schor, J., (1992), The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure, Basic Books.

Schor, J., (1998), Work, Free Time and Consumption, Time, Labour and Consumption: Guest

Editors Introduction, Time & Society, 7 (1): 119127.

Schwartz Cowan, R., (1983), More work for mother: the ironies of household technology from

the open hearth to the microwave, New York: Basic Books.

Dale Southerton and Mark Tomlinson

238 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005

Shove, E., (2003), Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality,

Oxford: Berg.

Southerton, D., (2003), Squeezing Time: allocating practices, co-ordinating networks and

scheduling society, Time & Society, 12 (1): 525.

Southerton, D., Shove, E. and Warde, A., (2001), Harried and Hurried: time shortage and coor-

dination of everyday life, CRIC Discussion Paper No. 47, The University of Manchester and

UMIST.

Sullivan, O., (1997), Time waits for no (wo)men: an investigation of the gendered experience of

domestic time, Sociology, 31 (2): 221240.

Thompson, C., (1996), Caring consumers: gendered consumption meanings and the juggling

lifestyle, Journal of Consumer Research, 22: 388407.

Thompson, E.P., (1967), Time, Work-Discipline and Industrial Capitalism: past and present, 38:

5697; reprinted in Flinn, M. and Smout, T. (eds), (1974), Essays in Social History, Oxford:

Clarendon Press.

Vanek, J., (1978), Household Technology and Social Status: Rising Living Standards and Status

and Residence Differences in Housework, Technology and Culture, 19: 36175.

Veblen, T., (1925), The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of institutions, London:

Allen & Unwin, rst published 1899.

Warde, A., (1999), Convenience food: space and timing. British Food Journal, 101 (7): 51827.

Warde, A., Tomlinson, M. and McMeekin, A., (2000), Expanding Tastes?: cultural omnivorous-

ness and social change in the UK, CRIC Discussion Paper No. 37, The University of Man-

chester and UMIST.

Warde, A. and Tampubolon, G., (2002), Social capital, networks and leisure consumption, The

Sociological Review, 50 (2): 15580.

Wouters, C., (1986), Formalization and Informalization: changing tension balances in civilizing

processes, Theory, Culture and Society, 3 (1): 118.

Zerubavel, E., (1979), Patterns of Time in Hospital Life, London: University of Chicago Press.

Pressed for time the differential impacts of a time squeeze

The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 2005 239

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Jazzed About Christmas Level 2-3Dokument15 SeitenJazzed About Christmas Level 2-3Amanda Atkins64% (14)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)