Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Brownfield Neg - Magallon Perry-2

Hochgeladen von

Morgan FreemanCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Brownfield Neg - Magallon Perry-2

Hochgeladen von

Morgan FreemanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

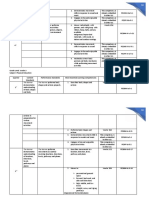

Brightfields Neg

Solvency Answers

No Solvency Capacity

Grid operators worry solar power takeover unimagineable.

JADHAV, May 18, 2011

(NILESH, Solar Energy Intermittency: Grid operators nightmare?, Solar Novus Today,

http://www.solarnovus.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2824:solar-

energy-intermittency-grid-operators-nightmare&catid=75:editors-blogs&Itemid=352, Aug 1,

12)MJG

However, grid operators worry when solar energy forms a significant portion of the generation

mix (say 10-30%). The concern is that such a scenario is unmanageable due to the fact that spinning

reserves and peak power generation capacity may not be sufficiently available. The conclusion

by some grid operators is that solar energy cannot really provide major share of electricity

generation, which could be bad news for grid-connected solar. This leads to the question of whether there is an upper limit on

grid-connected solar systems that is actually much smaller (e.g., <10%) than what many forecast today?

No Solvency Costs

Cant solve investment too expensive

GreenDIYenergy, 2010, Why is Solar Energy so Expensive? GreenDIYenergy,

http://www.egreendiyenergy.org/why-is-solar-energy-so-expensive/)

The fact is that the solar industry is not yet vast enough to create a market which can allow for

prices of solar panels and installation to drop. The more competition that is available, the

more these companies will compete against each other to attract buyers by lowering the prices. Solar

energy is still young, and as a result architects are timid about using these new solar technologies

on house designs. They may be timid becauase: They are unfamiliar with how to properly incorporate solar energy into

house designs that they have been doing for years. They are afraid of losing clients because solar energy adds to the overall project

cost. They are unsure of where to get the proper help and assistance to incorporate solar technology into their designs. Many

builders are about the bottom line, and the fact is that because solar energy is expensive, they dont

find it profitable for them to spend excessive architectural fees on designs and systems that

arent mainstream. Its a bit of a unfortunate loop, because this is a reason why solar energy is expensive, and because its

expensive this happens. Many people, especially in todays day in age, are all about the now. If people want

something, they do what they can to get it now. Unfortunately, the installation of solar panels is

an investment that may not necessarily see returns for the investor (homeowner or builder) until a

year, two years, or even five years after installation. There are a lot of short term concerns on peoples minds,

too many in fact that solar energy becomes just a nice thought in the back of peoples minds, and something to put off until later.

Many are waiting until solar energy is cheaper and economic, but it wont happen until people

start investing in it in the first place. I think the biggest reason why solar energy is so expensive, is because we dont

NEED it. Its a luxury right now, because we have many other energy sources so readily and cheaply available to us right now.

No Solvency Incentives 1NC

Even if plan provides incentives, companies will still only redevelop 1/3

of brownfield sites

Essoka 3 (Dumbe, Dr. of philosophy @ Drexel, Brownfields Revitalization

Projects:Displacement of the Dispossessed http://dspace.library.drexel.edu/handle/1860/206 )

Sites are categorized into three types: viable, threshold and nonviable. Viable sites are

already economically viable and the private market is taking steps to develop them.

Potential liability is low and the potential rate of return is high. Threshold sites are

marginally viable sites that cannot be developed without some public assistance. Nonviable

sites are tracts with a high potential for liability and/or a low economic advantagethey

require a substantial amount of public assistance

No Solvency Incentives 2NC/1NR

The problem of brownfields is too great to be solved by a single political

action

Kibel 98 (Paul Stanton, Adjunct Professor, Golden Gate University School of Law, Boston

College Environmental Affairs Law Review, 25 B.C. Envtl. Aff. L. Rev. 589, p. lexis)

The origins of suburban sprawl, toxic contamination, and inner-city decline are complex. Given

this complexity, there are no simple policy solutions to these problems. The scope and

interrelatedness of the issues do not lend themselves to tidy, reductionist answers. While there

may not be simple solutions, there are nonetheless specific and important policy steps that can be taken to improve the situation.

Particularly in the areas of metropolitan land governance and the remediation regulatory framework, there are policy options that

can and should be pursued. In the area of metropolitan land governance, there needs to be a

recognition that our municipal governments often lack the legal capacity to deal with the

problems facing our cities. n136 Jurisdiction over land regulation generally exists at the county

level, yet the problems of open space loss and inner-city disinvestment frequently operate on

a larger metropolitan scale. n137 As long as land-use planning, property taxes, and municipal

services are handled by county governments, different counties will lack either the means or

the incentive to deal with metropolitan-wide land-use problems. n138

No Solvency Grassroots Key 1NC

Government sponsored top-down solutions to the problems of

brownfields are doomed to failure due to their lack of focus on the

community

EPA 8 (6/6/08, NEJAC: Report on Public Dialogues - Key Issues in the Brownfields Debate

http://209.85.141.104/search?q=cache:n0_lvvakD98J:www.epa.gov/swerrims//ej/html-

doc/pub04.htm+Brownfields+racism+critical&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=us)

"Urban revitalization" is very different from "urban redevelopment." The two concepts are

not synonymous and should not be confused with each other. Urban revitalization is a

bottom-up process. It proceeds from a community-based vision of its needs and

aspirations and seeks to build capacity, build partnerships, and mobilize resources to

make the vision a reality. Revitalization, as we define it, does not lead to displacement of

communities through gentrification that often results from redevelopment policies.

Governments must not simply view communities as an assortment of problems but also

as a collection of assets. Social scientists and practitioners have already compiled

methodologies to apply community planning models. There must be opportunities for

full articulation of the importance of public participation in Brownfields issue. While

public participation is cross-cutting in nature, its meaning is shaped within the context of

concrete issues. It is not merely a set of mechanical prescriptions but a process of

bottom-up engagement that is "living." With regards to Brownfields and the future of

urban America, Public Dialogue participants were emphatic that "without meaningful

community involvement, urban revitalization simply becomes urban redevelopment."

No Solvency Grassroots Key 2NC/1NR

Public role key

EPA 8 (6/6/08, NEJAC: Report on Public Dialogues - Key Issues in the Brownfields Debate

http://209.85.141.104/search?q=cache:n0_lvvakD98J:www.epa.gov/swerrims//ej/html-

doc/pub04.htm+Brownfields+racism+critical&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=us)

The role of the public sector is one of the most pressing issues in present American political

discourse. The question reveals itself in virtually all issues surrounding the Brownfields

debate, including the future of cities, urban sprawl, economic and environmental

sustainability, racial polarization and social equity, defense conversion, transportation, public

health, housing and residential patterns, energy conservation, materials reuse, pollution

prevention, urban agriculture, job creation and career development, education, and the link

between living in degraded physical environments, alienation, and destructive violence.

Grassroots movements are key to environmental justice

EPA 95 (Office of Environmental Justice, 9 Admin. L. J. Am. U. 623, Fall, p. 661, LN)

[*661] CHAIRMAN MOORE: I would like to congratulate BIG for the very good work that is being done. I also wanted to

reinforce several of the comments that have been made. Many times, what ends up happening is that, we confuse what

environmental justice is really all about. There are many groups with various concerns. The concept of the

environmental justice movement cannot be viewed through one focal point. With that in mind, I

would hope that you take under consideration that there needs to be grassroots participation and

grassroots people speaking on behalf of themselves, and not many organizations that

claim to speak for grassroots people or for the environmental justice movement.

No Solvency Liability 1NC

Decreasing liability wont solve investor reluctance on Brownfields

multiple warrants

Meyer, Van Landingham 00 (Peter B and H. Wade, Director, Center for Environmental

Policy and Management and Assoc. CEPM , Reclamation and Economic Regeneration of

Brownfields, August, http://209.85.173.104/search?q=cache:Z0iHkcWafUIJ:www

.eda.gov/PDF/meyer.pdf+%22Brownfield+Sites:+Causes,+Effects,+and+Solutions%22&hl=en&ct

=clnk&cd=3&gl=us)

The continued relatively tight brownfields capital market appears to be due to a number

of different factors: -brownfields are often in neighborhoods with many problems other than contamination,

including poor infrastructure or transportation access, crime, and related ills (23, 97, 120, 121); -for a variety of reasons, urban

land is often less in demand than suburban or exurban sites, even in the absence of the complicating

factor of possible past contamination (20, 23, 96); -federally financed highways and other infrastructure

development, along with tax policies and other public policies, have tended to subsidize development of previously rural and

suburban land for decades, placing all urban land, and especially brownfields, at a further

competitive disadvantage (65, 102); -most brownfield sites, even those only suspected of having contamination, are

given valuations by appraisers that may exaggerate risks or costs, and thus face reduced

access to debt capital from institutions with prescribed loan-to-value ratios designed to

limit the risk exposures they accept (30, 94, 104); and, -continued investor concerns about

project viability and stability of cash flow for loan servicing, whether or not accurate in the changing

investment climate, limit the willingness of lenders to fund, regardless of property valuations (11, 46, 56, 112).

No Solvency Liability 2NC/1NR

Liability is just one of three key reasons for lack of brownfield investment-the

Aff doesnt solve cost and time overruns, community acceptance or lender

conservatism

Meyer, Van Landingham 00 (Peter B and H. Wade, Director, Center for Environmental Policy and Management and

Assoc. CEPM , Reclamation and Economic Regeneration of Brownfields, August,

http://209.85.173.104/search?q=cache:Z0iHkcWafUIJ:www

.eda.gov/PDF/meyer.pdf+%22Brownfield+Sites:+Causes,+Effects,+and+Solutions%22&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=3&gl=us)

While appraisers tend to discount excessively for stigma, they are correct in their perception that there are

exceptional risks associated with projects on sites that need to be remediated. Three major risks confront

investors in contaminated sites that are not present in other development projects: -possible cost (and time) overruns

in cleanup or containment operations; -possible liability claims arising from accidents or exposures to

contaminants in the past or during the cleanup; and, -future uncertainty about community acceptance of

the site redevelopment (leading to changes in marketability of the site, restrictions on

acceptable land uses, and possible additional cleanup requirements). While developers

appear to be increasingly willing to incur such risks, they tend to do so with other peoples

moneyand thus are constrained by appraiser and lender conservatism with respect to

brownfields (56, 81, 145).

No Solvency Liability SQ Solves 1NC

There are many measures that solve liability fears.

Sigurani 6 *Miral Alena, Assistant Attorney General, Brownfields: Converging Green,

Community, and Investment Concerns, AZ Attorney, Vol. 43, p. 38, December, l/n+

In addition, many private tools, such as environmental insurance policies and indemnification

provisions, have further reduced fears of potential liability. Some available types of

environmental insurance include: pollution legal liability insurance, remediation legal liability

insurance, defense coverage, remediation stop-loss insurance and contingent contractors

insurance. n29 Investors also may use indemnification provisions to shield themselves from

liability. Those provisions are private contractual mechanisms in which one party promises to

shield another from liability. n30

No Solvency Liability SQ Solves 2NC/1NR

Developers are comfortable with liability law, and incentives work

North and South Carolina prove.

Rodenberger 5 *Farah, Brownfields Programs and Tax Incentives are Stimulating the

Redvelopment of Brownfields Properties in North Carolina and South Carolina, Southeastern

Environmental Law Journal,

Southeastern Environmental Law Journal, Vol. 13, p. 119, Spring, l/n]

Private developers have benefited from well-defined liability protections, as well as an array

of financial incentives to evaluate and redevelop brownfields in North Carolina, South

Carolina, and across the country. n241 Since the enactment and reauthorization of the federal Taxpayer Relief Act,

n242 the federal government has offered tax incentives for eligible cleanup expenses to stimulate cleanups and redevelopments of

brownfields. n243 In North Carolina, tax incentives in the form of partial and graduated property exemptions for five years were

enacted in July 2001. n244 In South Carolina, more complicated corporate tax incentives were enacted

beginning in May 2002, such as tax credits, job tax credits, fees-in-lieu of property taxes, and

ad valorem tax exemptions. n245 The number of brownfields redevelopments has increased

dramatically since January 2002. n246 This increase indicates a growing comfort with

statutory protections from environmental liability, and proves that financial incentives may be

encouraging brownfields redevelopments in North Carolina and South Carolina.

No Solvency Tax Credits 1NC

Tax credits dont solve environmental justice fails in the most

depressed economic areas.

Green 4 (Emily A, Enviro Policy BS, 5 J.L. Socy 611, Winter, LN)

Michigan's Brownfield legislation assumes that private investors will view the tax increment

financing and small business tax credits as a [*612] prudent business investment. 250

This assumption may work for many areas, but not in the most depressed economic

areas. The success of incentives is particularly seen in areas where real estate is at a

premium and the economy is strong. It is in these areas that developers see little risk in their

investment. In some cases, municipal authorities report being passed over by developers, in which case the developer

absorbs the cost and passes it on to the consumer. 251 However, in most cases, the local authorities recruit developers. 252

No Solvency Generic

Implementation of Brightfields is too Unrealistic to be Successful

Riberio, 2007

(Lori *Harvard College; masters degree in environmental policy, MIT, developed the Brockton

Brightfields+ Waste to watts: A brightfield installation has the potential to bring renewed life

to a brownfield site, Refocus, Volume 8, Issue 2, MarchApril 2007, Pages 46-49,

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471084607700501, DJ)

The fatal flaws of the DOE's program were a failure to provide sufficient technical and financial

resources for Brightfield cities to succeed, an inability to build local capacity required to

ensure success, and an unrealistic business model that promoted small assembly plants in the

midst of an industry trend towards increasingly large factories. However, to install a utility scale

brightfield on an environmentally challenging site is an extraordinarily complex project that

most municipalities are ill-equipped to perform, particularly given the numerous state and federal policy barriers.

A community must undertake the sophisticated process of securing legislative/regulatory

approval, and then financing, developing, operating and maintaining a small power plant to

complete this type of brightfields project. Environmental conditions may require additional site preparation prior to

brightfield installation. Also, policy that encourages brightfield projects is doomed to fail without the tools and resources for

successful implementation.

Brightfield program unrealistic - inadequate government resources and

capacity building dedicated to program implementation

Ribeiro, 06

(Lori *Harvard College; masters degree in environmental policy, MIT, developed the Brockton

Brightfields] "Does it Have to be So Complicated? Municipal Renewable Energy Projects in

Massachusetts," http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/37677, DJ).

The US Department of Energy conceived the Brightfield program, which requires significant technological

innovation and sophistication at the local level, without providing sufficient resources.

Funding, technical assistance and capacity building resources provided were not

commensurate with the program goals. DOE announced a program at the outset of its initial

experiment without designing the experiment for learning. By establishing its program role as

a facilitator, DOE did not design the program with due consideration to the implementation

difficulties that would follow. Further, one of the DOE's core concepts for local job creation

was based on a flawed understanding of the solar photovoltaics industry it was trying to

support.

Brightfield projects likely to fail - complexity of joint action

Ribeiro, 06

(Lori *Harvard College; masters degree in environmental policy, MIT, developed the Brockton

Brightfields] "Does it Have to be So Complicated? Municipal Renewable Energy Projects in

Massachusetts," http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/37677, DJ).

The implementation of the Brightfield project involved numerous institutional stakeholders at

the local, state and Federal levels, all with different roles, perspectives and levels of urgency.

There were too many decision clearances required to ensure project success; it was achieved

only through a confluence of key success factors. As the analysis will show, even with an

extremely high probability of success at each decision point, the odds were 2:1 that the

project should have failed.

Brightfields difficult to develop - lots of support structure requirements

Millennium Energy LLC, 01

(Technical and Economic Feasability Assessment of a Brightfield Photovoltaic Power Plant at

Miramar Landfill, http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy01osti/30478.pdf, 8/4/12 ERW)

Independent of the system type selected (stationary fixed axis or tracking) it will require a mounting

support structure. Mounting structures are typically made of steel, and are designed to meet parameters allowing for 90

mph 3-second gust and 50 year design wind speeds. Installation of the mounting structure will require minor

excavation into the landfill cap. However, the base of the mounting structure only needs to be

buried approximately 2-4 feet below ground, which may be shallower than the final cap

depth. Prior to finalizing the PV plant site, the City should determine the cap depth at the specific site to ensure that the

mounting structure does not penetrate the landfill cap. Minimal disturbance to the existing landfill site would occur as a result of

site preparation and installation activities, and would be limited to minor grading and minor excavation associated with setting the

mounting structure. Landfill sites have limited options for development, primarilyMillennium Energy LLC 5 Brightfield Feasibility

Assessment February, 2001 NREL Task Ordering Agreement # KDC-0-30470-00 due to concerns of soil settlement. Since

settlement defines the very nature of landfills, further investigations should be undertaken to determine

impacts on the system and ongoing maintenance requirements. Alternatives to steel support structures include

modules that can be placed directly on the ground with a mat backing; however, significant

reduction of peak power output would be experienced with ground-placed modules (hence

diminishing project economics). In addition, there may be issues associated with dirt build up

from heavy rain and run off (further degrading module performance), and impacts on landfill

maintenance.

Effective solutions to brownfields must consist of BOTH cleanup and

pollution prevention

EPA 8 (6/6/08, NEJAC: Report on Public Dialogues - Key Issues in the Brownfields Debate

http://209.85.141.104/search?q=cache:n0_lvvakD98J:www.epa.gov/swerrims//ej/html-

doc/pub04.htm+Brownfields+racism+critical&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=us)

Likewise, pollution prevention must be integrated into all Brownfields projects as an

overarching principle. Brownfields projects can provide unique opportunities to apply

the pollution prevention concept in practical ways. Most Brownfields communities have

both cleanup and toxic release problems. Turning them into livable communities means that

both have to be addressed. For example, if you do cleanup without pollution prevention, the

same set of problems will reemerge. The community must be involved in developing pollution

prevention strategies because they often have the most practical and innovative ideas. Pollution prevention must be

integrated into all Brownfields projects as an overarching principle. Brownfields

projects can provide unique opportunities to apply the pollution prevention concept in

practical ways. Most Brownfields communities have both cleanup and toxic release

problems. Turning them into livable communities means that both have to be addressed.

For example, if you do cleanup without pollution prevention, the same set of problems

will reemerge. To date, the concept of pollution prevention has been noticeably absent

from the Brownfields dialogue. To avoid yet another generation of Brownfields,

pollution prevention must be aggressively introduced before plans for redevelopment

have become entrenched. Education about pollution prevention must take place at the

earliest stages

Development of brownfields is very expensive

Momber 6 (Major Amy L., Chief of Environmental Torts in the Environmental Litigation

Branch, Environmental Law and Litigation Division, Air Force Legal Operations Agency

http://web.lexis-

nexis.com/scholastic/document?_m=92503b1285bdb498d702653402a08fda&_docnum=1&wch

p=dGLbVlb-zSkVk&_md5=78b15cc1a5cd75355c33f6ca0949ea58)

The wide range of possible latent variations in site conditions, daunting complexity of

relevant environmental laws, ambiguity as to exposure for personal and property

damages, and inability to get enough information to sufficiently characterize a site

before work begins, may preclude an accurate appraisal of the actual liability risks

involved in a project and expose federal remediation contracting parties to staggering

unanticipated expenses. 46 Therefore, the government and remediation contractors cannot presume that

the anticipated cost of a cleanup is definite--even when preliminary precautions (i.e.,

assessments, [*73] inspections, investigations, studies, and designs) have been taken. 47 Rather, in some cases, unexpected

areas of contamination are not unearthed until the remedial action phase is well

underway. 48 Such a discovery can send once economically feasible projects well into the

"red." To understand why the government and government contractors take on these risky projects, it is useful to examine the

dynamics that motivate them.

Economy Answers

Green Economy Answers 1NC

Solar energy infeasible- raises energy costs

Institute for Energy, 12

(July 20, Solar Subsidies Make Electricity Bills More Expensive

http://www.canadafreepress.com/index.php/article48216, 8-4-12, acm)

Most importantly, Germanys solar subsidies have been expensive with little evidence to prove they

are worth the cost. Last year over 8 billion ($10.2 billion was paid out to German solar farm

operators and homeowners with solar panels, but only 3.3 of the countrys power supply was

generated by solar in the same time period. Two decades of highly-subsidized renewable energy have had a noticeable effect

on the countrys electricity prices. Currently, Germanys solar feed-in tariffs vary from $0.166 per kWh on the low end to $.0297 PKH

on the high end, which makes it $0.2315 per kWh on average. This represents a large portion on the price of residential electricity:

an average customer in Germany pays about $0.3523 per kWh or electricity used. Those who

believe that the Unites States should emulate Germanys model should consider the following: 35 cents per kWh

for electricity is three times as much as U.S. customers paid on average for electricity last year

(11.8 cents pKw). Germanys solar feed Germanys solar feed-in tariff alone is 41-152% greater than the US total residential

electricity rates. Germans also have the 2

nd

highest electricity prices in Europeoutdone only by wind-

dependent Denmarkand this situation will inevitably be made worse by the face that Germany has pledge to phase out nuclear

energy and become more reliant on renewable energy sources.

Green Economy Answers 2NC/1NR

Solar energy hurts economyexpensive and kills jobs

Aszkler, 11

(July 11, The Real Cost of Solar Enery,

http://www.americanthinker.com/2011/07/the_real_cost_of_solar_energy.html#ixzz22dFHaXE

P, acm)

The economy of scale makes apparent the physical impossibility of solar harvesting. Using the

sun to provide 50% of America's electricity needs would necessarily cover tens of thousands of

square miles with solar panels and mirrors, with all of it costing tens of trillions of dollars. From

the study commissioned by the University of Juan Carlos and the Juan de Mariana Institute, since 2000 Spain spent

571,138 to create each "green job", including subsidies of more than 1 million per wind industry job. Two

thirds of jobs were in construction, fabrication and installation, one quarter in administrative

positions, marketing and projects engineering, and just one out of ten jobs has been created

at the more permanent level of actual operation and maintenance of the renewable sources of electricity.

The programs creating each green job also resulted in the destruction of 2.2 jobs elsewhere in the country for

every "green job" created. In the end the price of electricity paid by the consumer in Spain will have to be

increased 31% to be able to repay the historic debt generated by the deficit produced by the

subsidies to renewable. Once the panels are constructed, the cold, hard reality of solar energy's 33% efficiency shines as

hot as the midday sun. One can clearly see the massive government subsides required to keep solar

plants operating while never achieving anywhere near breakeven return on investment.

Environmentalists still proudly promote the green advantages of solar while glossing over the facts:

US Solar Energy not competitiveChina is ahead

Martin and Snyder, 12

(Christopher Martin and Jim Snyder, Jun 29, 2012, Abound Failure Revives Debate Over Obama

Solar Policies http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-06-29/abound-failure-revives-debate-

over-obama-solar-policies.html acm)

Abound Solar Inc., a U.S. solar manufacturer that was awarded a $400 million loan guarantee in

2010, said yesterday it will suspend operations and file for bankruptcy next week. Abound said its thin-

film panels couldnt compete against Chinese products, the same reason cited by Solyndra LLC, which closed

its doors in August after receiving a $535 million guarantee from the same program. Half of the four solar

manufacturers that received loan guarantees have failed, supporting the argument that backing clean-

energy is a mistake, according to Representative Cliff Stearns. We know why they went bankrupt. We warned them they

would go bankrupt, Stearns, a Florida Republican, told reporters yesterday. The larger question is why the

administration was pursuing a green-energy policy in which companies are going bankrupt

and wasting taxpayer money. Stearns is chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committees oversight panel that

has held hearings on the Energy Departments loan guarantee program. Representative Jim Jordan, an Ohio Republican and

chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committees stimulus oversight panel that has investigated loan

guarantees to solar companies, said Abounds failure is further proof the Energy Department program was a mistake. It just adds to

the weight of how ridiculous this was, Jordan told reporters. Abound plans to file for bankruptcy in Wilmington, Delaware,

next week and will fire about 125 employees, according to a statement yesterday. The company, based in Loveland,

Colorado, borrowed about $70 million against its guarantee. U.S. taxpayers may lose $40 million to $60 million

on the loan after Abounds assets are sold and the bankruptcy proceeding closes, Damien LaVera, an Energy

Department spokesman, said in a statement. When the floor fell out on the price of solar panels, Abounds product was no longer

cost competitive,LaVera said. Abound stopped production in February to focus on reducing costs after a global oversupply and

increasing competition from China drove down the price of solar panels by half last year. Aggressive pricing actions

from Chinese solar-panel companies have made it very difficult for an early stage startup company like

Abound to scale in current market conditions, the company said in the statement.

Energy is really expensive, especially after brightfield development.

Millennium Energy LLC, 01

(Technical and Economic Feasability Assessment of a Brightfield Photovoltaic Power Plant at

Miramar Landfill, http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy01osti/30478.pdf, 8/4/12 ERW)

In conducting these "base case" analyses, the net present value of the project benefits was

derived through the summation of the projected annual revenues from energy generated by

the plant over its expected thirty year life. These revenues were calculated based upon an

assumption that the value of the energy generated in the base year of operations was equal

to 16 cents/kWh (i.e., the commodity price of energy sold from the plant, or the cost of utility provided energy displaced

from the on-site PV plant, is equal to 16 cents per kWh). This value was calculated based on prevailing market

conditions in the San Diego region from January through December 2000. The SDG&E General

Service "A" rate tariff was used as a proxy for this assessment. This assumption for the value

of power generated is a conservative estimate based on a mix of high and low monthly

average energy prices during this period ranging from a low of under 10 cents/kWh to a high

of over 26 cents/kWh. It should be noted that as recently as January of 2001, average

monthly retail energy prices have reached nearly 30 cents/kWh. After the base year, a 3% per

year energy price escalator was included in the analysis to account for future energy price

increases and inflation. These annual revenues were then discounted by the appropriate

discount rate tied to the financing option, and then summed over the thirty-year period.

Solar energy hurts economyprograms fail, jobs lost

Garate, 12

(Jessica, June 28, 2012, Schott Solar shuts down; 250 lose jobs,

http://www.krqe.com/dpp/news/breaking_news/250-lose-jobs-as-schott-solar-closes 8-4-2012

acm)

Schott Solar never lived up to its promises of high-paying jobs, and now with the decline of the U.S. Solar

industry is shutting down its New Mexico plant. That means 250 people are going to be out of a job. Schott Solar

started telling their employees at the Albuquerque plant at Mesa del Sol Thursday afternoon. One part of their plant will

close Friday laying off 200 people. The rest of the operation will ramp down over the summer June 28, 2012with the

remaining 50 workers losing their jobs then. In January 2008 Schott announced its intentions to build a plant year. It opened its

doors in Albuquerque in May 2009 promising 1,500 jobs but at its peak only employed 350 Schott

makes solar panels and sells them mostly to businesses. Company officials say they chose New Mexico

because of the abundance of sunshine and the qualified workforce. The $130 million in incentives

didn't hurt either. Now three years later the company is closing. Schott did not release a statement

Thursday instead saying it will comment after all employees have been told about the closing. Over the last year, solar

operations have been shutting down across the United States unable to keep up with the

china and its lower-cost manufacturing processes.

Failed Solar programs cost taxpayers millions

Nikolewski, 12 Capital Reporter

(Rob, July 1, 2012 State out $16m in Schott closure

http://newmexico.watchdog.org/14413/state-out-16m-in-schott-solar-closure-its-infuriating-

susana-says/ 8-4-2012 acm)

Schott received millions from various government entities in New Mexico to relocate here. But while

Bernalillo County and the City of Albuquerque will receive some of the money back it gave Schott

Solar in Local Economic Development Act funding, its now been learned that none of the $16 million it received from

the state of New Mexico under the guidance of then-Gov. Bill Richardson will have to be returned. From KOB-TVs

Chris Ramirez: The County and City will get all or part of the funds back because they negotiated claw back provisions. And since

SCHOTT Solar did not meet its obligations, the governments are entitled to recoup the funds. However, KOB 4 On Your Side

uncovered a document that reads the State of New Mexico specifically requested that no performance claw backs be tied to their

contribution. That means while the City and County are entitled to get funds from SCHOTT Solar, the Bill Richardson Administration

negotiated a $16 million loss for the State. We showed the documents to current Governor Susana Martinez. The State did not want

(claw back provisions) under the Richardson Administration, Martinez said. They basically gave away taxpayer dollars with no

consequences. Its infuriating because they took tax dollars, state money and ran and we cant get any of it back.

The Richardson administration was a big backer of green energy development and had hopes for

creating a Solar Valley in New Mexico that could rival the Silicon Valley but many of the investments never got off

the ground

Jobs Answers 1NC

Green Jobs another excuse to regulate business and hurt economy

Quiroz-Martinez, Fall 2010

(Julie, Beyond Green Jobs, The Public Eye, Vol. 25, No. 3,

http://www.publiceye.org/magazine/v25n3/beyond-green-jobs.html, Aug 1, 2012)MJG

But organized opposition to green jobs does exist; in fact it thrives among conservative thought

leaders and business groups, who view any push for an environmentally sustainable economy

as simply an excuse to further regulate business. The influential Heritage Foundation, for one,

claims that a green economy is a contradiction in terms, an approach that will eliminate more

jobs than it would create. [4] Heritage also argues that green jobs are anti-free enterprise, propped

up by government subsidies. It even pokes fun at green jobs, asking, as Peter Brookes and J. D. Foster do on the Heritage website,

What could be greener than a rickshaw?

Jobs Answers 2NC/1NR

Studies prove job creation is a myth

Quiroz-Martinez, Fall 2010

(Julie, Beyond Green Jobs, The Public Eye, Vol. 25, No. 3,

http://www.publiceye.org/magazine/v25n3/beyond-green-jobs.html, Aug 1, 2012)

As part of their overall effort to influence public understanding and public policy regarding

pollution and climate, the Kochs have funded efforts to discredit green jobs ideas and

programs. According to the Greenpeace report, their dollars supported the widely publicized

Spanish study 2009 research by an economics professor from Madrid arguing that Spains policy commitment to

renewable energy development had cost the country 2.2 jobs for each clean-energy job

created. With initial support from the Koch-funded Institute for Energy Research, the study gained followers in key

venues such as a Heritage Foundation briefing in Washington, DC, and a Congressional

Western Caucus hearing, in which Phil Kerpen, the policy director of the Koch-funded Americans for Prosperity (AFP),

testified. While the Department of Energy and others have challenged the validity of the study [8], it continues to bounce on the

internet and in public debate

Solar energy destroys jobs

Alvarez; Merion Jara; Rallo Julian, 2009

(Gabriel, King Juan Carlos University Research director, Raquel Merino Jara, King Juan Carlos

University Researcher, Juan Ramn Rallo Julin, King Juan Carlos University Researcher, Study

of the effects on employment of public aid to renewable, King Juan Carlos University,

http://www.juandemariana.org/pdf/090327-employment-public-aid-renewable.pdf, Aug 4, 12,

p.29)MJG

This result is important, since although solar energy may on paper appear to employ many workers

(essentially in the plants construction), the reality is that for the plant to work, it requires consumption of

great amounts of capital that would have instead created many more jobs in other parts of

the economy. Inversely, wind power, while still noxious in its economic impact when coercively introduced through state

intervention, wastes far fewer resources per megawatt of installed capacity and thus does not destroy as many jobs in the rest of

the economy.

Environmental Justice Answers

Environmental Justice Bad Frontline 1NC

1. The reductiveness and intersectionality of the environmental justice

movement cause it to deny the agency of distinct minority groups and

threaten their survival.

Yamamoto and Lyman 1 (Eric K, Hawaii Law School law prof., and Jen-L W, UC Berkeley

visiting law prof., University of Colorado Law Review, 72 U. Colo. L. Rev. 311, Spring, p. 311-313,

ln)

"Racial communities are not all created equal." 1 Yet, the established environmental

justice framework tends to treat racial minorities as interchangeable and to assume for

all communities of color that health and distribution of environmental burdens are main

concerns. For some racialized communities, 2 however, environmental justice is not only, or

even primarily, about immediate health concerns or burden distribution. Rather, for them, and

particularly for some indigenous peoples, environmental justice is mainly about cultural and

economic self-determination and belief systems that connect their history, spirituality, and

livelihood to the natural environment. 3 This article explores the meaning of "environmental justice," focusing

on race as it merges with the environment. The word "environment" triggers images of the physical surroundings - water, [*312]

trees, ecosystems. 4 Society tends to separate physical environment from social environment - the latter including people, culture,

and social structures. 5 But the "race" in "environmental racism" suggests that the physical and

the social are integrally connected. Indeed, understanding "our environment" is

impossible without understanding both its physical and social aspects, and their

interplay. 6 Much of the scholarly writing on environmental justice does not address

with adequate complexity or depth the interplay between the natural and the racial.

Rather, many articles make unexplored assumptions about racialized environments,

failing to inquire into distinct cultural and power differences among communities of

color and their relationships to "the environment." For instance, while some might describe

the siting of a waste disposal plan near an indigenous American community as

environmental racism, that community might say that the wrong is not racial

discrimination or unequal treatment; it is the denial of group sovereignty - the control

over land and resources for the cultural and spiritual well-being of a people. Alternatively,

the community might say that the siting is, on balance, desirable because it provides

needed jobs in the area and is an aspect of group economic survival.

2. The race-based politics of the environmental justice movement

reconstitutes racism and precludes unity.

Shellenberger 8 (Michael, environmental strategist, March/April, Utne Reader, Complete

Interview: The Temperature Transcends Race, p. 6, http://www.utne.com/2008-03-

01/Environment/Complete-Interview-The-Temperature-Transcends-Race.aspx)

Ever since we wrote Death of Environmentalism weve been in various debates about environmental justice. We decided to do

the chapter in part because so many people said, Well, environmental justice is the expansive environmentalism. And

we went and looked at it and read a huge amount and interviewed many dozens of people, and what you find is a movement

that looks at the intersection of race, class, and pollution, which actually makes that

movement smaller not larger. And frankly, you didnt ask it, but Ill say it anyway: We think that a race-based

politics is toxic, and completely outmoded, and that we should not be organizing as different races. Race is

itself a very dubious concept and construct. Were a single human race and well do far

better organizing across race lines than within them. If you look at where the

environmental justice movement has gotten into trouble, its where you find a lot of

infighting often between different races, different ethnic groups. It hasnt actually served to be

a unifying movement. To say race is itself a very dubious concept and construct is one thing, but to say that it doesnt

play a role in how communities suffer is another. Well of course. Of course theres racism. And of course there are

racial disparities, but thats different from organizing as Latinos or as African

Americans or as whites. I just dont believe that thats a positive expansive politics. Its important to

organize outside of racial and environmental categories. The fact that pollution is a

problem does not necessarily lead you to creating a pollution-based politics. And the fact

that racism is a problem does not mean that you should have a race-based politics. The

goal of the original civil rights movement was to put an end to race-based politics not to

reconstitute it.

3. Environmental justice advocates ignore the economic complexities of

life for indigenous peoples, threating their survival while transforming

them into environmental mascots.

Yamamoto and Lyman 1 (Eric K, Hawaii Law School law prof., and Jen-L W, UC Berkeley

visiting law prof., University of Colorado Law Review, 72 U. Colo. L. Rev. 311, Spring, p. 320-322,

ln)

The framework, however, at times also undercuts environmental justice struggles by

racial and indigenous communities because it tends to foster misassumptions about race,

culture, sovereignty, and the importance of distributive justice. Those misassumptions sometimes

lead environmental justice scholars and activists to miss what is of central importance to affected communities. The first

misassumption is that for all racialized groups in all situations, a hazard-free physical

environment is their main, if not only, concern. 47 Environmental justice advocates foster this notion by placing

emphasis on "high quality environments" 48 and the adverse health effects caused by exposure to air pollutants and hazardous

waste materials. [*321] Not all facility sitings that pose health risks, however, warrant full-scale

opposition by host communities. Some communities, on balance, are willing to tolerate

these facilities for the economic benefits they confer or in lieu of the cultural or social disruption that

might accompany large-scale remedial efforts. Other communities, struggling to deal with joblessness,

inadequate education, and housing discrimination, indeed with daily survival, prefer to

devote most of their limited time and political capital to those challenges. In these situations,

racial and indigenous communities may have pressing needs and long-range goals beyond the re-siting of polluting facilities. 49

For example, as Native communities endeavor to ameliorate conditions of poverty and social

dislocation by encouraging the economic development of tribal lands, some increasingly

find themselves in conflict with environmentalists, who are sometimes but not always environmental

justice advocates. In the mining industry, several Native American tribes are attempting to tap mineral resources on their

reservations. 50 Urged by the increased emphasis on economic self-determination in federal

Native American policy in the 1970s, the tribes formed the Council of Energy Resource

Tribes to deal [*322] with both the siting of new mines on Native American lands and the

environmental and the cultural problems that might result. 51 Those efforts met stiff opposition from

some environmental groups concerned mainly with land degradation and pollution. The environmentalists' seeming

lack of understanding of the economic and cultural complexity of the Native American

groups' decisions have led some Native Americans to express cynicism about

environmentalists who sometimes treat them as mascots for the environmental cause.

4. Environmental justice prevents communities from solving poverty

and public health.

Glasgow 5 (Joshua, Yale Law School JD candidate, Buffalo Environmental Law Journal, 13 Buff.

Envtl L.J. 69, Fall, ln)

Some environmental justice advocates oppose compensated siting proposals on moral grounds.

Robert Bullard has coined the term "environmental blackmail" to refer to such plans. 210 Vicki Been usefully classifies these

moral objections into four broad categories. 211 First, LULUs involve risks to health some argue should not be commodified. 212

This argument is generally unpersuasive. Society commonly allows individuals to take risks in

exchange for compensation. Many professions include a risk premium that provides

additional compensation for abnormally dangerous jobs. More importantly, it is not

clear that a community that accepts a LULU is actually increasing its total level of risk.

The increased income that a compensation package provides can decrease countervailing

risks associated with poverty. Compensation [*121] can pay for health-care costs or

better nutrition, the benefits of which may exceed the risks associated with a LULU. 213 Second, compensated siting

proposals may result in disproportionate siting. Poor communities may value the compensation a LULU

offers more than wealthier communities because of the declining marginal utility of

capital. Some environmental justice advocates find such an outcome inherently unjust.

214 If compensation mechanisms are carefully crafted to avoid disparities in bargaining power, such a disparity should be

recognized as an accurate gauge of community preferences. Siting a LULU in the community that values a compensation package

the most increases total utility in the same way any competitive market transaction does.

5. Policies protecting environmental justice only cause minorities to

suffer more by denying these groups job opportunities and further

suppressing them into racial stereotypes

Payne 00 (Henry

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1568/is_n5_v30/ai_21141903/print?tag=artBody;col1)

The EPA's policy and its application in Louisiana have enraged and confused governors, mayors, and

environmental officials across the nation. These officials see the administration's efforts not

as environmental justice but as a policy of environmental redlining that effectively

excludes minority areas from badly needed business investment. Chris Foreman, a political scientist

at the Brookings Institution and author of a forthcoming book on environmental justice, laments the administration's racial

politicization of the permitting process. "Environmental justice is not fundamentally racial," Foreman

says. "But Title VI invites race-based claims." He says accusations of environmental racism are

"dubious, but politically compelling. No one wants to be called a racist." In its zeal to apply Title

VI civil rights law to industrial emissions, Foreman contends, the administration has obscured the real health problem that

threatens communities like Romeville: poverty. State and local governments across the nation have felt

Louisiana s pain. Despite the national economic boom, black unemployment remains over 9 percent,

and local governments are scrambling to attract industries to state enterprise zones and

brownfields. In addition to the U.S. Conference of Mayors, local organizations and business groups throughout the country

have lined up to condemn the EPA's environmental redlining policy. City officials are lobbying the company to build the new

facility in one of the majority-black city's many brownfield sites. But as long as the EPA rule is in effect, says

Michigan environmental chief Harding, "G.M. will not build in Lansing. They'll buy farmland

somewhere instead. The loser won't be the company; the losers will be the workers and

cities." Says Steve Serkaian, media relations director for Lansing Mayor David Hollister: "What does this have to do with civil

rights? If these plants don't build in these communities, [residents] will suffer from

malnutrition, not pollution."Fifty-seven percent of the population living within five miles of Ford's truck assembly

plant in Dearborn, for example, is minority, as compared to 16 percent of the state's population. As a result, when Ford sought to

update its paint operations this year, local activists threatened it with an environmental racism complaint, delaying the company's

permit for four months. In the highly competitive auto marketplace, which measures new model development in months, Ford is

concerned that the EPA's policy could create a nightmare of red-tape delays. "It seems like the

EPA is setting up an almost endless adversarial process," Ford executive Tim O'Brien told The Detroit

News.

Environmental Justice Bad Native Americans 2NC/1NR

Extend Yamamoto and Lyman 1 the environmental justice movement

dehumanizes Native Americans by painting them as deeply and extremely connected

to the environment so that they may be used as mascots, while in reality Native

Americans struggle to survive and must occasionally allow environmental harm to

do so. When this occurs, environmental justice advocates backlash against the

Native Americans, representing a racism grounded in stereotypes of over-

expectation.

The framework of environmental justice disregards and threatens the

survival of Native Americans.

Yamamoto and Lyman 1 (Eric K, Hawaii Law School law prof., and Jen-L W, UC Berkeley

visiting law prof., University of Colorado Law Review, 72 U. Colo. L. Rev. 311, Spring, p. 338-339,

ln)

James Huffman also criticizes the traditional environmental justice framework, but from the perspective of

Native American economic development. He identifies three assumptions of modern environmental thought that work against

Native [*339] interests. 164 First, orthodox environmentalism assumes the existence of a

scientifically "correct" natural condition and thus tends toward oppressive command

and control methods. 165 The second assumption is that regulations must limit development and

growth. 166 Finally, in marked contrast to arguments that anthropocentrism in American environmentalism clashes with

Native cultural beliefs, Huffman asserts that American environmentalism assumes a "biocentric"

approach fundamentally opposed to economic development, even when necessary for

Native survival. 167 He criticizes environmental protection as a "luxury good" enjoyed by wealthier

societies 168 that promotes the idea that "the poverty and economic depression of the

reservations [is] not only inevitable but desired." 169 Huffman's critique is harsh: "Native

Americans, more than any other segment of American society, will suffer at the altar of

environmentalism worshipped in their name." 170 Commentator Conrad Huygen arrives at a similar

conclusion: "We have romanticized indigenous cultures in a manner that threatens to stifle

development on reservations and perpetuate the poverty that permeates them." 171 In more

measured terms, Tsosie agrees with Huffman's view that "national implementation of centralized policies

(whatever their origin and content) often disregards tribal sovereignty and the special interests of

indigenous peoples." 172

The environmental justice movement disenfranchises racial groups,

especially Native Americans.

Yamamoto and Lyman 1 (Eric K, Hawaii Law School law prof., and Jen-L W, UC Berkeley

visiting law prof., University of Colorado Law Review, 72 U. Colo. L. Rev. 311, Spring, p. 335, ln)

Some commentators on environmental racism treat the meaning of race with sophistication.

101 The established framework, however, tends to engender formal-race analysis and thus

to encourage writing about environmental racism without [*329] explanation of, or sometimes

even use of, the term, "race." 102 By not acknowledging race and racial context, these writings are limited. However

otherwise illuminating, they do not address: (1) racial groups' (or subgroups') differing

understandings of "the environment," and of "race" itself; (2) groups' differing spiritual,

cultural, and economic connections to the environment; and (3) the importance of the

environment to the groups' identities. By treating all racial groups alike, they fail to

provide analytical and organizational frameworks for understanding specific

environmental justice problems and for tailoring actual remedies to meet the needs and

goals of different racial communities. The writings tend to embody a one-size-fits-all approach, overlooking

distinct historical experiences of particular communities of color and their current cultural and economic concerns. 103 In doing

so, the writings sometimes ignore the distinct sovereignty-based claims of Native Americans.

104 For example, [*330] stories of waste disposal on Native American reservations recently

inspired a series of derisively titled news articles, "Dances with Garbage." 105 The

Campo Band in California decided to build a waste landfill on its reservation, sparking

vehement protest not from tribal members, but from non-Native local residents. 106 In New

Mexico, the Mescalero Apaches are negotiating with a private company to locate a monitored, retrievable storage nuclear waste

facility on their lands, inciting the wrath of non-Native neighbors. 107 These stories turn sideways traditional

environmentalist notions of Native Americans as the primitive foot soldiers in the war

against pollution. The disputes also destabilize the conventional wisdom of the

environmental justice movement that opposes as discriminatory the siting of the same

sort of waste disposal facilities that some Native tribes are cautiously inviting onto their

lands. 108 Viewed paternalistically, the question might be: Are the tribes acting against

their better judgment, imperiling both the environment and themselves? Viewed

critically, the question might be different: Are the tribes, after calculation, exercising

rights of self-determination [*331] in order to build an economic base to assure cultural

and political survival?

Environmental Justice Bad Poverty 2NC/1NR

Extend Glasgow 5 that environmental justice impairs efforts to solve poverty and

public health locally unwanted land uses rejected by environmental justice

activists often pose little health risk to communities, as in the case of a landfill.

However, they also usually provide jobs and revenue for a community, elevating

communities from poverty and increasing a communitys potential for public health

facilities.

Environmental justice abandons opportunity for solving poverty and

public health.

Evans 98 (Jill E, Samford U associate law prof., Challenging the Racism in Environmental

Racism: Redefining the Concept of Intent, Arizona Law Review, 40 Ariz. L. Rev. 1219, p. 1258-

1260, ln)

Economic critics of the "environmental racism" theory also argue that there are trade-offs at play in mitigating

siting disputes and point out that minority communities have in many instances

supported siting toxic facilities in their communities. 192 The possibility of jobs and other

perceived economic benefits induce city leaders in poorer communities suffering from

"rising unemployment, extreme poverty, a shrinking tax base, and a decaying business

infrastructure" 193 not only to welcome, but to actively encourage, the location of a toxic facility in

their community. 194 These communities become ripe for exploitation by polluting industries anxious to avoid a NIMBY

195 -triggered protest. Economic incentives and [*1259] monetary inducements pave the way for unopposed facility siting 196

because, as one commentator asserted, if many low income communities are to lift themselves out of

poverty, they must support the construction of job creating projects... Recycling plants, sewage

treatment plants, sewage sludge treatment units,...any many others are, ironically, environmentally both necessary and

controversial. It is past time to abandon the reflexive notion that every major construction is

an evil that must be fought. 197 A clear example of the impact of economic incentives is found in the Emelle

incinerator operated by Chemical Waste Management ("CWM"). The Emelle facility in Sumter County, Alabama is the nation's

largest hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facility. 198 Sumter County is rural and poor, nearly 70% of the

population is black, 199 and 90% of the black residents lived in poverty at the time of siting. 200 According to WMX

Technologies, of which CWM is a subsidiary, the Emelle facility has brought substantial revenues into a county which, at 14.4%,

had one of the state's highest infant mortality rates. 201 Since the siting of the Emelle facility, the infant mortality rate dropped to

8.5%, lower than the state infant mortality rate of 11%. 202 Emelle employs 300 people on an annual payroll of $ 10 million, with

60% of the employees living in Sumter County. 203 The revenue brought in by the landfill, in addition to

providing employment, has been used to improve schools, build the local fire station and town

hall, as well as improve health care delivery. 204

The environmental justice movement prevents creation of energy plants

where they could boost health and create jobs.

Kaswan 3 (Alice, U San Francisco law prof., March, North Carolina Law Review, 81 N.C.L. Rev.

1031, March, p. 1058-1060, ln)

Moreover, many LULUs bring a mix of benefits and burdens. For some communities, the

benefits could outweigh the burdens, with the net result that an arguably "undesirable" land use becomes, overall,

a desirable land use. 219 Professor Blais reflects this possibility in her use of the term "environmentally sensitive land uses" rather

than "locally undesirable land uses," 220 and in referring to possible "differentials" in facility distribution patterns rather than

"disproportions." 221 The benefits could include direct services, such as medical care needed

within the community. 222 Many LULUs, both industrial and service-oriented, could bring

significant employment [*1080] opportunities to a community. 223 A significant enterprise could

improve an area's tax base. 224 Moreover, some communities are plagued by abandoned properties,

industrial and otherwise, that degrade the community environment. 225 A LULU might

be considered an improvement on the existing environment, notwithstanding certain undesirable

features. The movement to develop "brownfields" - former industrial properties - reflects the judgment that communities

could improve their lot by encouraging the development of new facilities on existing abandoned,

industrial properties. 226

Environmental justice targets facilities important for minority

employment.

Kaswan 3 (Alice, U San Francisco law prof., March, North Carolina Law Review, 81 N.C.L. Rev.

1031, March, p. 1081, ln)

Professor Blais argues that poor or minority residents may choose to live close to environmentally

sensitive land uses due to the job opportunities and other benefits such uses provide. 480

By way of example, she describes how industrial development in Richmond, California, attracted residents

during the last century. 481 In the 1940s, war-based production, in particular, attracted southern African-

Americans seeking employment. 482 Although the Richmond example has been used by

environmental justice advocates "to provide evidence of the injustice of the existing

distribution of [*1137] environmentally sensitive land uses," 483 Professor Blais concludes that

"the fact that most of its residents are minorities appears to be directly attributable to

individual choices to seek employment in a highly industrialized area." 484

Environmental Justice Bad Racism 2NC/1NR

Extend Shellenberger 8 that environmental justice movements recreate racism by

focusing the movement on race, environmental justice advocates create infighting

between political groups that skewers the movement while simultaneously

encouraging new racism against the majority or between minorities.

Environmental justice is defined by perspectives of intrinsic whiteness

and elitism, creating an exclusionary silence in racial issues.

Yamamoto and Lyman 1 (Eric K, Hawaii Law School law prof., and Jen-L W, UC Berkeley

visiting law prof., University of Colorado Law Review, 72 U. Colo. L. Rev. 311, Spring, p. 347-348,

ln)

Critical race theory also facilitates interrogation of the often unexamined influences of whiteness on environmental law, policy,

and practice. According to Peter Manus, the environmental movement, from which environmental justice springs in

part, "is determined by the norms or perceptions of white mainstream America." 210 Manus

thus attributes the tension between environmentalism and other social justice

movements to environmentalism's "elitist roots, conceived of and implemented primarily

from a white, male, and mainstream perspective" and to its resulting "proclivity to

immerse itself in pure science, as opposed to human science, and to express itself in

command-and-control regulation, as opposed to consensus." 211 To what extent, if at all, is this true?

Critical race theory helps us grapple with this question by unpacking whiteness. In law, whiteness is the racial

referent - "inequality" means "not equal to white." Whiteness is the norm. 212 Yet whiteness

itself, until recently, has been largely unexplored. Critical race theorists and historians are now unraveling the often hidden

strands of white influence and privilege and the ways in which whiteness (as a norm and as a racial identity) dramatically, yet

quietly, shapes all racial relationships. 213 Joe Feagin observes the following about the influence of Anglo law, religion, and

language. [*348] From the 1700s to the present, ... immigrant assimilation has been seen as one-way, as conformity to the

Anglo-Protestant culture: "If there is anything in American life which can be described as an overall American culture ... it can

best be described ... as the middle-class cultural patterns of largely white Protestant, Anglo-Saxon origins." 214 White influence is

so pervasive that it often goes unnoticed. It is, according to Barbara Flagg, "transparent": In this society, the white

person has an everyday option not to think of herself in racial terms at all. In fact, whites

appear to pursue that option so habitually that it may be a defining characteristic of whiteness ... . I label the tendency

for whiteness to vanish from whites' self-perception the transparency phenomenon. 215

Integral to this transparency is "the very vocabulary we use to talk about

discrimination." 216 "Evil racist individuals" discriminate; by implication, all others do

not. This vocabulary hides "power systems and the privilege that is their natural

companion." 217 Critical race theory thus pushes environmental justice proponents to

examine the white racism (and sometimes the racism by other groups) that undergirds

the environmental problems affecting Native communities and communities of color. It

also challenges proponents to closely interrogate the influence of whiteness in environmental

law, policy, and practice, and its effect, in turn, on established approaches to environmental justice

controversies.

Environmental justice depoliticizes race to allow aversion of racial

issues.

Yamamoto and Lyman 1 (Eric K, Hawaii Law School law prof., and Jen-L W, UC Berkeley

visiting law prof., University of Colorado Law Review, 72 U. Colo. L. Rev. 311, Spring, p. 336, ln)

What O'Neill identifies and what is missing from many other commentators' accounts is an express understanding of how race

and culture operate in contemporary U.S. communities. Racial categories are not biological realities.

Rather, they are socially constructed by culture, politics, history, and human interaction.

138 By perceiving race as fixed and objective - instead of socially constructed - the

established environmental justice framework tends to treat "race [as] a neutral,

apolitical term, divorced from social content" 139 and devoid of cultural meaning. This

further reflects the inclination of many courts and commentators to avoid facing race

through the "painful revelations that may be lurking in an examination of either racial

history or the current racial disparities of society." 140

The environmental justice movement cant solve racism it denies the

uniqueness and culture of individual identity groups.

Yamamoto and Lyman 1 (Eric K, Hawaii Law School law prof., and Jen-L W, UC Berkeley

visiting law prof., University of Colorado Law Review, 72 U. Colo. L. Rev. 311, Spring, p. 323, ln)

Finally, the established framework tends to assume that all racial and indigenous groups,

and therefore racial and indigenous group needs, are the same. 62 In general, it assumes that in terms

of cultural needs and political-legal remedies, one size fits all. This simplifying assumption is rooted in the

longstanding perception of many disciplines that race is fixed and biologically

determined rather than socially constructed and that it is, therefore, largely devoid of cultural

content. It is also rooted in the related perception that skin color and hair type are the

reason for ill-treatment by some, but are otherwise irrelevant to social interactions - that

beyond biological distinctions, all people (and groups) are essentially the same. 63 A number of

courts and environmental justice scholars make this simplifying assumption about race and culture.

The Affs distributive environmental justice precludes deeper social

movements.

Kaswan 3 (Alice, U San Francisco law prof., March, North Carolina Law Review, 81 N.C.L. Rev.

1031, March, p. 1058-1060, ln)

Writing in political philosophy, Professor Iris Marion Young has suggested a deeper critique of a focus on distributive justice.

Like Professor Foster, she argues that focusing on distributive justice could fail to address the deeper

social problems that cause disparities to arise 110 because it presupposes rather than

scrutinizes institutional structures and processes. 111 Ultimately, a primary focus on distribution could

implicitly support unjust institutions, since it takes [*1059] them as given. 112 Her concern is not just with the study of

discrimination, however, but the development of distributionally-based remedies. For example, affirmative action

efforts tend to focus on distributions: who gets employment or opportunities for higher

education. That focus fails to address such critical underlying structural issues as who

decides who is "qualified" for employment and why some have the means to attain these

qualifications while others do not. 113 A focus on distribution is ultimately depoliticizing,

Professor Young argues, because potential challenges to the existing systems of power and

control become rechanneled into distributive "solutions" that dissipate the thrust of

critical social movements. 114 Professor Young does not argue that distributive justice is irrelevant, 115 but she does

argue that issues of political and social justice should be the primary focus. Professor Young's

concern that a preoccupation with distributive justice could lead to a failure to question and

challenge unjust social and institutional structures is an important caution. If the environmental

justice movement were reduced to simply counting how many facilities end up here and

there, then critical aspects of the movement would indeed be lost. Many environmental justice

leaders are not simply challenging the number of facilities to which they are subject, but also the fairness of decision-making and

underlying power structures. 116 Challenging environmental decisions is one step in a broader engagement over the nature of

economic and political power. The goal of sustained challenge is a greater political voice - a voice that may transcend particular

disputes over particular facilities. 117 It is also important to identify the widespread inequities [*1060] that may lie behind

current land use distributions. Furthermore, addressing political and social processes will also likely improve distributive justice

given their role in causing disparities. Nonetheless, given the difficulty of devising effective remedies for many past and present

forms of political and social injustices, 118 and the real world consequences of distributional inequities, I argue that it is

appropriate for the movement to direct at least some of its efforts toward distribution-focused remedies.

Environmental Justice Bad Survival 2NC/1NR

Extend Yamamato and Lyman 1 that environmental justice threatens minority

survival because many minority groups, especially indigenous peoples, require the

plants and companies attacked by the environmental justice movement for jobs and

economic survival. The environmental justice movement both ignores the special

economic condition of these groups and ignores their perceptions of environmental

justice as a tool to regain their sovereignty rather than as a tool of

environmentalism.

Environmental Justice Bad Reductive 1NC

The reductiveness of environmental justice movements precludes a

broader effort to end social and racial injustice.

Shellenberger 8 (Michael, environmental strategist, March/April, Utne Reader, Complete

Interview: The Temperature Transcends Race, p. 1-2, http://www.utne.com/2008-03-

01/Environment/Complete-Interview-The-Temperature-Transcends-Race.aspx)

What started out as an effort to make environmentalism more expansive ended up making it

even more narrow. The challenges facing poor communities of color go way beyond air and

water pollution. They have far less access to healthy food; they have less health care security,

less child care security. Theyve got crappier schools. Theres more stress and

disempowerment. So to create a politics thats centrally focused on toxic contamination or

diesel bus pollution is reductive and speaks to a set of things that are very low priorities in

comparison to the much bigger factors driving health and life outcomes. Are you saying that low income communities,

particularly communities of color, dont bear a larger burden of environmental degradation? No. We say very clearly that poor

communities of color do bear a heavier burden in terms of pollution and environmental impact. The point that we

make is that what gets defined by environmental justice advocates as environmental impacts are

not the most serious factors determining health outcomes. In other words, smoking, diet, probably

even things like stress related to living in an environment thats high in violence and

insecurity. Those are much more powerful factors shaping life and health outcomes and an

expansive movement would deal with all of those problems simultaneously, not just with the ones that are

defined as environmental.

Environmental Justice Bad Reductive 2NC/1NR

Environmental justice fails to address the broad threats to minorities.

Utne Reader 8 (Environmental Justice for All, March/April,

http://www.truthout.org/docs_2006/030908G.shtml)

In their 2007 book Break Through: From the Death of Environmentalism to the Politics of Possibility, authors Ted Nordhaus and

Michael Shellenberger take issue with this strategy (see "The Temperature Transcends Race"). They argue that some of the research

conducted in the name of environmental justice was too narrowly focused and that activists have

spent too much time looking for conspiracies of environmental racism and not enough time

looking at the multifaceted problems facing poor people and people of color. "Poor Americans

of all races, and poor Americans of color in particular, disproportionately suffer from social ills

of every kind," they write. "But toxic waste and air pollution are far from being the most serious

threats to their health and well-being. Moreover, the old narratives of intentional

discrimination fail to explain or address these disparities. Disproportionate environmental

health outcomes can no more be reduced to intentional discrimination than can

disproportionate economic and educational outcomes. They are due to a larger and more

complex set of historic, economic, and social causes."

Alt Cause Income

Alt cause - income is correlated with living in environmentally damaged

areas

Downey 5 (Liam, University of Colorado Faculty Associate in Population Program and CU

Population Center The Unintended Significance of Race: Environmental Racial Inequality in

Detroit, Social Forces, 83, 3, 8/1/12, 971-972) CMAP

For example, several environmental inequality studies have found environmental hazards to be

distributed equitably according to race in areas where they are distributed inequitably

according to income, despite the fact that minorities generally earn significantly less than

whites (Anderton et al. 1994a; Oakes, Anderton, and Anderson 1996; Yandle and Burton 1996). But if income is negatively associated