Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Total Quality Management As The Basis For Organizational Transfor

Hochgeladen von

hemarajputOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Total Quality Management As The Basis For Organizational Transfor

Hochgeladen von

hemarajputCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Southern Cross University

ePublications@SCU

Teses

2005

Total quality management as the basis for

organizational transformation of Indian Railways: a

study in action research

Madhu Ranjan Kumar

Southern Cross University

ePublications@SCU is an electronic repository administered by Southern Cross University Library. Its goal is to capture and preserve the intellectual

output of Southern Cross University authors and researchers, and to increase visibility and impact through open access to researchers around the

world. For further information please contact epubs@scu.edu.au.

Publication details

Kumar, MR 2005, 'Total quality management as the basis for organizational transformation of Indian Railways: a study in action

research', DBA thesis, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW.

Copyright MR Kumar 2005

Southern Cross University

Doctor of Business Administration

Total Quality Management as the basis for organizational

transformation of Indian Railways A Study in Action Research

Researcher: Madhu Ranjan Kumar

Student ID: 21231263

i

Table of Contents

Abstract .................................................................................................................. xiv

Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................. 1

1.1 Background to research.................................................................................................................................. 1

1.2 Research problem............................................................................................................................................ 2

1.2.1 Research pathway......................................................................................................................................3

1.2.2 Contribution...............................................................................................................................................4

1.3 Justification for research................................................................................................................................ 4

1.3.1 Need to change for Indian Railways..........................................................................................................5

1.4 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................... 6

1.5 Outline of this thesis........................................................................................................................................ 6

1.6 Limitations....................................................................................................................................................... 8

1.7 My own value system as a researcher............................................................................................................ 8

2.0 Conclusion...................................................................................................................................................... 10

Chapter 2 Literature Review.................................................................................. 11

2.1 Parent discipline............................................................................................................................................ 13

2.1.1 Parent discipline 1-Organisational Change..............................................................................................13

2.1.2 Parent discipline 2 Total Quality Management.....................................................................................15

2.1.2.1 Historical background......................................................................................................................15

2.1.2.2 Commonalty among quality gurus:..................................................................................................18

2.1.3 TQM as a philosophy of change..............................................................................................................21

2.2 Immediate discipline ..................................................................................................................................... 23

2.2.1 Total Quality Management- a systems perspective.................................................................................23

2.2.1.1 TQM and System Dynamics............................................................................................................29

2.2.1.2 Systems theory, TQM and organisational learning..........................................................................31

2.2.1.3 Organisational knowledge creating process.....................................................................................33

2.2.1.4 Learning and second order change..................................................................................................35

2.2.2 Critical success factors for TQM.............................................................................................................36

2.2.3 Different International Quality Awards...................................................................................................38

2.2.3.1 History of quality awards.................................................................................................................39

2.2.3.2 Commonality and differences among different quality awards.......................................................41

2.2.3.3 Change in the criteria of quality awards over time..........................................................................42

ii

2.2.3.4 Commonalities and differences between DP (2004) and MBNQA(2004)......................................45

2.2.3.5 TQM and awards in public sector....................................................................................................47

2.2.3.6 TQM in India and Indian quality awards.........................................................................................49

2.2.3.7 Indian quality awards vs. MBNQA & EQA ....................................................................................53

2.2.4 Synthesis of system dynamics, CSFs and quality award criteria.............................................................56

2.2.5 Total Quality Management and ISO........................................................................................................58

2.2.5.1 ISO 9000:2000 and TQM................................................................................................................60

2.2.5.2 Factors affecting transition from ISO to TQM................................................................................64

2.2.5.3 Quality movement in India and ISO................................................................................................65

2.2.6 TQM and culture.....................................................................................................................................67

2.2.6.1 Indian work culture..........................................................................................................................70

2.2.6.2 Duality of traditionalism and modernism in Indian culture.............................................................73

2.2.6.3 Recent changes in Indian work culture............................................................................................74

2.2.6.4 Nurturant task leadership.................................................................................................................76

2.2.6.5 Juxtaposition of culture for TQM and Indian culture......................................................................77

2.2.6.6 Comparison between J apanese culture and Indian culture...............................................................79

2.2.7 Indian Bureaucracy..................................................................................................................................80

2.2.7.1 Characteristics of Indian bureaucracy.............................................................................................81

2.2.7.2 Changing the bureaucracy...............................................................................................................83

2.2.7.3 TQM and change in government bureaucracy and in public sector.................................................86

2.2.7.4 Summary of TQM in bureaucracy..................................................................................................88

2.2.8 TQM and transformational leadership.....................................................................................................89

2.2.8.1 Impact of cultural factors on transformational leadership...............................................................91

2.2.8.2 Transformational leadership in India...............................................................................................92

2.3.Summary of literature review and overview of the central problem........................................................ 93

2.4. Identification of the gaps which need investigation.................................................................................. 97

Chapter 3 Research questions and research methodology ............................... 98

3.1 Research questions ........................................................................................................................................ 98

3.2 Different research paradigms..................................................................................................................... 100

3.3 Development of research map.................................................................................................................... 106

3.4 Research Design for stage 1........................................................................................................................ 108

3.4.1 Survey A - Assessment of organisational policies and practices in the Indian Railways......................108

3.4.2 Survey B - Assessment of cultural values of Indian Railway personnel ..............................................109

3.5 Research design for stage 2......................................................................................................................... 111

3.5.1 Survey C Assessment of the impact of ISO 9000 in the Indian Railways..........................................112

3.5.1.1 Sampling plan for survey C...........................................................................................................112

3.5.2 Survey D - Development of scale to measure the transition of ISO certified organisations towards TQM

........................................................................................................................................................................124

3.6 Questionnaire design and administration for survey D........................................................................... 124

3.6.1 Development and evaluation of questionnaire.......................................................................................125

3.6.2 Development of measurement scale......................................................................................................129

3.6.3 General issues in drafting the questionnaire..........................................................................................129

3.6.4 Pre-test, revision and final draft ............................................................................................................130

3.6.5 Reliability and validity of the instrument..............................................................................................130

3.6.6 Survey method.......................................................................................................................................133

3.7 Research design for stage 3......................................................................................................................... 133

3.7.1 Development of research design for stage 3..........................................................................................133

iii

3.8 Ethical considerations ................................................................................................................................. 134

3.9 Conclusion.................................................................................................................................................... 135

Chapter 4 Data collection and data analysis.......................................................136

4.1 Data collection and data analysis for survey A......................................................................................... 136

4.2 Data collection and data analysis for survey B......................................................................................... 143

4.2.1 Data collection.......................................................................................................................................143

4.2.2 Data Analysis........................................................................................................................................144

4.3 Data collection and data analysis for survey C......................................................................................... 148

4.3.1 Understanding the impact of ISO implementation on railway units in terms of intervening variables.149

4.4 Data collection and data analysis for survey D......................................................................................... 150

Chapter 5 The action research project ................................................................153

5.1 Situating Action Research in a Research Paradigm................................................................................. 153

5.2 Situating action research within systems theory ...................................................................................... 158

5.2.1 Soft System methodology......................................................................................................................158

5.2.2 Soft system methodology as action research.........................................................................................160

5.3 Justification of Action Research as the research methodology for this thesis........................................ 161

5.4 Research model for Action Research......................................................................................................... 164

5.5 Rigour and validity in the Action Research.............................................................................................. 167

5.5.1 Falsification...........................................................................................................................................170

5.5.2 Reflection and three levels of learning..................................................................................................171

5.5.3 Intervention...........................................................................................................................................175

5.5.4 General criteria for assessing rigour in AR...........................................................................................176

5.5.5 Rigour and validity in this Action Research..........................................................................................177

5.6 Action research at Jhansi Stores Depot..................................................................................................... 180

5.6.1 Selection of unit for action research......................................................................................................180

5.6.2 About J hansi Stores Depot....................................................................................................................180

5.6.3 The action research cycles.....................................................................................................................182

5.6.4 Experiential learning during action research.........................................................................................198

Chapter 6 Reflection after action and development of TQM transition model

................................................................................................................................203

6.1 Reflection after action................................................................................................................................. 203

6.1.1 Reflection after action- 1.......................................................................................................................203

6.1.2 Reflection after action- 2.......................................................................................................................207

6.1.3 Reflection after action- 3.......................................................................................................................209

6.1.4 Reflection after action- 4.......................................................................................................................210

6.1.5 Development of TQM transition model ................................................................................................214

6.2 Jhansi revisited............................................................................................................................................ 219

iv

6.2.1 The next action cycle.............................................................................................................................223

6.2.2 Action Research revisited......................................................................................................................226

6.3 Validation of the TQM transition model................................................................................................... 227

Chapter 7 Conclusion ...........................................................................................231

7.1 Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 231

7.2 Conclusions about research problems....................................................................................................... 231

7.3 Conclusion about research issue ................................................................................................................ 234

7.4 Assessment of Rigour in this Action Research.......................................................................................... 237

7.5 Contribution to literature........................................................................................................................... 238

7.5.1 Findings which support the existing literature......................................................................................238

7.5.2 Finding which is contrary to existing literature.....................................................................................239

7.5.3 Findings which are contribution to existing literature...........................................................................239

7.6 Contribution to policy and practice........................................................................................................... 240

7.6.1 Implications for Indian Railways..........................................................................................................240

7.6.2 Implications for Indian organisations....................................................................................................241

7.6.3 Implications for organisations in general ..............................................................................................242

7.7 Contribution to methodology ..................................................................................................................... 242

7.8 Limitations................................................................................................................................................... 243

7.9 Implications for future research ................................................................................................................ 244

Chapter 8 Researchers ruminations ...................................................................245

References .............................................................................................................254

Appendices ............................................................................................................281

Appendix 1. Tables and figures about quality awards................................................................................... 281

Appendix 2. Assessment of organisational policies......................................................................................... 301

Appendix 2A Summary of responses to question no.II to question no. VI of the questionnaire assessment of

organisational policies (Survey A)................................................................................................................311

Appendix 3. Behaviour preference scale ( S 004) ........................................................................................... 321

Appendix 3A Data analysis for the questionnaire S004 (survey B)............................................................... 328

Appendix 4. ISO 9000 Survey .......................................................................................................................... 338

Appendix 4A Summary of survey C in six ISO certified units of Indian Railways.......................................350

Appendix 5. TQM transition questionnaire.................................................................................................... 355

Appendix 6. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire ...................................................................................... 369

Appendix 6.1 Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire Leader Form................................................................372

Appendix 6.2 Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire Rater Form..................................................................375

Appendix 6.3 Scores obtained on the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (rater form).............................384

v

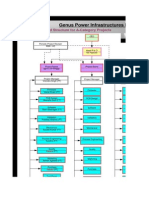

Appendix 7. Organization chart of Indian Railways...................................................................................... 385

Appendix 8. Intimation about co- action researchers .................................................................................... 386

Appendix 9. List of ISO certified units in the Indian Railways..................................................................... 389

Appendix 10. Organisational Chart of Jhansi workshop unit of Indian Railways...................................... 393

vi

List of Figures

Figure 2. 1 Concept map for literature review......................................................................... 12

Figure 2. 2 The yin-yang of TQM........................................................................................... 15

Figure 2. 3 Simplified example of an organization as a system.............................................. 26

Figure 2. 4 Milestones of organisational roots........................................................................ 28

Figure 2. 5 Milestones of quality development....................................................................... 28

Figure 2. 6 Quality and business results.................................................................................. 29

Figure 2. 7 Modes of knowledge creation in an organization................................................. 34

Figure 2. 8 The four types of learning as polar opposites........................................................ 35

Figure 2. 9 European Quality Model ....................................................................................... 41

Figure 2. 10 Model of a process-based quality management system...................................... 61

Figure 2. 11 Characteristics of internal work culture of organizations in developing countries

in the context of their sociocultural environment............................................................ 68

Figure 2. 12 Nurturant-Task leadership process leading to participative management........... 76

Figure 2. 13 Socio cultural factors in MBNQA and J QA....................................................... 78

Figure 2. 14 Summary of literature review and gaps in existing literature............................ 96

Figure 3. 1 Different assumptions about nature of reality..................................................... 101

Figure 3. 2 Research map..................................................................................................... 107

Figure 3. 3 Existing functional silos in Indian Railways....................................................... 117

Figure 3. 4 Model of a process-based quality management system...................................... 119

Figure 3. 5 Plan for development of TQM transition questionnaire .................................. 124

Figure 5. 1 The action research cycle.................................................................................... 153

Figure 5. 2 The experiential learning cycle........................................................................... 154

Figure 5. 3 The oscillation between reflection and generalisation........................................ 155

Figure 5. 4 Conceptual link between TQM and AR.............................................................. 164

Figure 5. 5 Two-project model for AR based thesis.............................................................. 165

Figure 5. 6 Research model used in stage 3 shown within the AR framework..................... 166

Figure 5. 7 The ORJ I within experiential learning cycle....................................................... 175

Figure 5. 8 Model for validation of learning which occurred in each cycle by using different

methods, different sources of data and different types of data...................................... 178

Figure 6. 1 Model for sequential development of TQM factors using the ISO framework.. 215

Figure 6. 2 Model for implementation of TQM in India using the ISO framework.............. 218

Figure 7. 1 Reproduction of Figure 2.14 showing gaps in existing literature....................... 235

Figure 7. 2 Model for implementation of TQM in Indian Railways using the ISO framework

thereby filling up the gap shown in Figure 7.1.............................................................. 236

Figure 8. 1 The structure of an appreciative system.............................................................. 248

vii

Figure 8. 2 Unbundling of standards of fact and value into three components of time, person

and ecology and their positioning along the Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft continuum.

....................................................................................................................................... 250

Figure 8. 3 Integration of mode 2 of SSM with context sensitivity and balancing............... 252

viii

List of Tables

Table 2. 1 Traditional change model vs. complex adaptive change model ............................. 14

Table 2. 2 Commonalities among seminal TQM work........................................................... 19

Table 2. 3 Definition of variable for enablers.......................................................................... 30

Table 2. 4 Definition of variables for results........................................................................... 31

Table 2. 5 Differences in checklists of Deming prize 1992 and Deming prize 2000.............. 43

Table 2. 6 Differences in the criteria of MBNQA 1992 and MBNQA 2004.......................... 44

Table 2. 7 Major Indian National Quality Awards.................................................................. 52

Table 2. 8 Comparison of Indian Quality Awards with MBNQA & EQA ............................. 54

Table 2. 9 CSFs for TQM and CEBEA criteria....................................................................... 55

Table 2. 10 ISO 9000 and Demings system of profound knowledge.................................... 62

Table 2. 11 Comparison of MBNQA, EFQM and ISO 9000......................................................... 63

Table 2. 12 Societal values of Indian managers after liberalisation........................................ 75

Table 2. 13 Comparison between vertical collectivism and horizontal collectivism.............. 79

Table 3. 1 Research questions for this work............................................................................ 99

Table 3. 2 Basic belief systems of alternative enquiry paradigms......................................... 102

Table 3. 3 Quality criteria for different research paradigm................................................... 104

Table 3. 4 Typology of sampling strategies in qualitative inquiry........................................ 113

Table 3. 5 Analysis of different categories of railway units on clauses of ISO 9000:2000.. 120

Table 3. 6 Percentiles for individual scores, based on others ratings on MLQ.................... 123

Table 3. 7 Operationalisation of different factors of TQM transition questionnaire ......... 128

Table 3. 8 Summary of scores obtained on the TQM transition questionnaire by DP winners

in India and ISO certified different units of Indian Railways........................................ 132

Table 4. 1 Respondent profile for survey A........................................................................... 136

Table 4. 2 Comparison of codes developed in survey A with the CSFs of TQM................. 139

Table 4. 3 Existing and proposed organisational dimensions for Indian Railways by senior railway

managers......................................................................................................................... 142

Table 4. 4 Number of respondents in different categories for survey B................................ 144

Table 4. 5 Scores obtained on the three dimensions of status consciousness (S),

personalised relationship (P) and dependency proneness (D) by different categories

of employees of Indian Railways................................................................................... 145

Table 4. 6 List of short-listed railway units for survey C...................................................... 148

Table 4. 7 Comparison of scores on TQM transition questionnaire of different units of

Indian Railways and the juxtaposition of intervening factors....................................... 151

Table 5. 1 Comparison between three paradigms of knowledge........................................... 156

Table 5. 2 Comparison between positivist science and action research................................ 157

Table 5. 3 Dimensions of SSM types.................................................................................... 159

Table 5. 4 First order, second order and third order learning................................................ 173

Table 5. 5 Skills of balancing inquiry and advocacy............................................................. 174

Table 5. 6 Types of intervention............................................................................................ 176

Table 5. 7 The AR cycles....................................................................................................... 183

Table 6. 1 Different types of power....................................................................................... 204

ix

Table 6. 2 Components of transformational leadership and their proposed Indian cultural

equivalent....................................................................................................................... 210

Table 6. 3 Improvement steps identified in May 2004 and their status in December 2004.. 221

Table 6. 4 Comparison of scores on TQM transition questionnaire of different units of

Indian Railways and the juxtaposition of intervening factors including no. of CPA and

no. of reward.................................................................................................................. 228

Table 7. 1 Assessment of rigour in this action research thesis.............................................. 237

Table 7. 2 Components of transformational leadership and their Indian cultural equivalent 240

x

Abbreviations

AL Action Learning

AMM Assistant Materials Manager

AMV Alambagh Warehousing Unit

AR Action Research

avg average

BEM Business Excellence Model

BPL Bhopal Workshop

BPO Business Process Outsourcing

CEBEA Confederation of Indian Industries Exim Bank Excellence Award

CEE Chief Electrical Engineer

CFA Critical Factor Analysis

ckt circuit

CLW Chittaranjan Locomotive Works

CME Chief Mechanical Engineer

CPO Chief Personnel Officer

COS Controller Of Stores

CWM Chief Workshop Manager

cert certificate

CII Confederation of Indian Industries

CII_EXIM Confederation of Indian Industries Bank Excellence Award

coop cooperation

CPA Corrective and Preventive Action

CSF Critical Success Factor

CWM Chief Workshop Manager

del delivery

DCW Diesel Components Works

DLW Diesel Locomotive Works

DEE Divisional Electrical Engineer

DME Divisional Mechanical Engineer

DMM District Materials Manager

doc document

DP Deming Prize

DRM Divisional Railway Manager

Dy CMM Deputy Chief Materials Manager

EFQM European Foundation Quality management

EQA European Quality Award

EXIM Export Import Bank

FA&CAO Financial Advisor and Chief Account Officer

GM General Manager

HPO High Performance Organisation

ICF Integral Coach Factory

info information

ISO International Standards Organisation

J PY J apanese Yen

J USE Union of J apanese Scientist and Engineers

Lit Literature

M&M Mahindra & Mahindra

MBNQA Malcolm Baldridge National Quality Award

xi

mgt management

MLQ Multi Factor Leadership Questionnaire

M.R. Management Representative

NC Non Conformance

n.d. no date

NDDB National Dairy Development Board

NQA National Quality Award

NT Nurturant Task

OHSAS Occupational Health and Safety Management System

perf performance

plg planning

PRL Parel Workshop

proc process

QC Quality Control

QMS Quality Management System

RCF Rail Coach Factory

reduc reduction

resp responsibility

ret rm retiring room

RWF Rail Wheel Factory (the current name of WAP)

shop workshop

sp qual special quality

SQC Statistical Quality Control

SSM Soft System Methodology

stat tech statistical technique

sup supervisor

sys system

TOR Turn Over Ratio

TQM Total Quality management

trg training

WAP Wheel and Axle Plant

xii

Statement of original authorship

This is to certify that this research work titled Total Quality Management as the basis for

organisational transformation of Indian Railways is an original work carried out by me.

Research work of other authors have been reproduced with due credit.

Madhu Ranjan Kumar

madhu_ranjan@yahoo.com

The author can be contacted at madhu_ranjan@yahoo.com for permission to take copies of

this thesis.

xiii

Acknowledgements

At the outset, I wish to thank my research guide Prof. Shankar Sankaran whose

guidance and incisive comments made this research work more rigorous. Southern Cross

University and its support staff can be rated as the most helpful team for a research work. The

library staff of SCU deserve a special thanks for their very prompt delivery of many research

papers and book sections. My special thanks goes to Ms Sue White who, as the DBA

administrator, was a constant source of support.

This is the perhaps the first ever doctoral level organisational study on Indian

Railways. I wish to thank the Department of Personnel & Training and the Ministry of

Railways of the Government of India for sponsoring this study. It is perhaps a measure of

change in thinking within the Indian government that it sponsored an in-depth academic study

of the largest bureaucracy in India with a view to bring about fundamental change in it.

A major part of the work involved collecting data at different railway units and

conducting surveys with railway employees from supervisors to chairmen. This is an occasion

to express my gratitude to hundreds of such respondents whose names cannot be individually

mentioned here for want of space. My special thanks go to the action research team at the

J hansi warehousing unit for their illuminating insights and the desire to run AR cycles.

Mr. Arif Zama deserves a special mention here for his painstaking feeding of data

collected into the computer and also for his enormous help in developing software which

helped in organising the data. That made the quantitative data analysis much easier.

I am thankful to Prof P. Khandwalla, ex. Director, I.I.M. Ahemadabad, Prof U.H.

Acharya of Indian Statistical Institute, Banglore, Prof J .B.P. Sinha of Assert Management

Institute, Patna and Prof. S.G.Deshmukh of I.I.T Delhi for their permission to use their

questionnaire in this thesis.

xiv

Abstract

The basic objective of this research was to assess the suitability of Total Quality

Management (TQM) via the International Standards Organization (ISO) 9000/2000 quality

accreditation system route for bringing about organisational transformation in the Indian

Railways and to develop an India specific model for taking an ISO certified organization

towards TQM.

The first part of the research aimed at getting the as is and should be status of

Indian Railways from an organisational change point of view. Based on the work carried out

by Khandwalla (1995), a series of open-ended and close-ended questions were asked to the

senior members of Indian Railways. Analysis of their responses was undertaken. It indicated

that the way they thought Indian Railways should change was in line with the TQM model of

change.

The culture-TQM fit was studied as a part of this research. Hierarchy (or power

distance) and its related concept collectivism were identified as the two cultural constructs

which affect the successful implementation of TQM. The second part of the research aimed at

measuring the hierarchical orientation among the employees of Indian Railways. This was

measured on three dimensions of dependency proneness, personalised relationship and

status consciousness based on the work done by Sinha (1995). It was found that among the

three dimensions, status consciousness and dependency proneness were more deeply

entrenched cultural traits among Indian Railway employees as compared to personalised

relationship. On the two dimensions of status consciousness and dependency proneness,

the class 1 officers of Indian Railways were less hierarchy conscious than the class 2 officers

who, in turn, were less hierarchy conscious than the supervisors. The tendency for

personalised relationship did not vary significantly either across the class 1 officer, class 2

officer and supervisor categories or across different age groups. Further, employees less than

30 years old, from 31 years to 50 years old and more than 50 years old, demonstrated similar

level of status consciousness and dependency proneness. This shows that at least in the

Indian Railways, even among the younger generation, notwithstanding 15 years of

liberalisation, hierarchical orientation continues to be a powerful cultural trait.

The third part of the research aimed at understanding the impact of ISO 9000

implementation in the Indian Railway units. It was found that, contrary to the literature, there

xv

was no resistance to implementation of ISO based change in the Indian Railways. This

research argues that because of their strong sense of identity with their work group, the

employees of Indian Railways are more amenable to an internal leader initiated change.

Hence there was no resistance to change.

The fourth part of the research was an action research project aimed at ISO 9000:2000

certification of a warehousing unit in the Indian Railways. This was carried out to investigate

the way organisational learning occurred during ISO certification. Three action cycles were

conducted over a period of two months. Seven months later, one additional cycle was

completed. Special care was taken to see that the conclusions arrived after one cycle were

validated from other sources. It was found that departmentalism and lack of team spirit are

major problems in Indian Railways. Both are ascribed to the caste system in India. It is

hypothesised that since an Indian Railway employee remains in a department throughout

his/her career, the department becomes his/her professional caste. The research then

identifies an Indianised version of leadership in the context of organisational change. It

hypothesises that hierarchical teacher-student (guru-shishya) relationship with the leader

invokes personal bases of power which promotes change in India. The teacher-student (guru-

shishya) relationship with the leader is conceptually similar to intellectual stimulation factor

of transformational leadership. The personalised relationship with a more equitable slant can

be elevated to the status of individualised consideration factor of transformational leadership

and the Nurturant Task (NT) leadership model of India is conceptually similar to the

contingent reward factor of transformational leadership.

In the context of TQM, this research hypothesises that there is a sequential

relationship among the critical success factors (CSFs) of TQM. For this, one should begin by

framing process-based quality procedures and quality objectives. Process based quality

procedures and quality objectives lead to development of team orientation in the context of

TQM implementation. Similarly, a multi-tier Corrective and Preventive Action (CPA)

reinforced with a reward and recognition system, positively intervenes in the transition of an

ISO certified organization towards TQM.

The learning arrived at in different parts of the research was finally integrated into a

model for transforming an ISO certified unit towards TQM. The model shows that

propagation of customer satisfaction as a value and not just as a measurement- as in a

customer satisfaction index is key for replacing some of the dysfunctional traditional Indian

values which do not fit in a liberalised economy. More specifically, the compulsion of

xvi

implementing a Corrective / Preventive Action makes a person come out of his/her

traditional moorings and thus begins his/her socialisation outside his/her professional caste.

The reinforcing effect of successive improvement inculcates a feeling of team spirit among

members of different functional groups. Successive CPAs supported by a suitable reward

system and an Indianised version of leadership mentioned earlier create a spiral vortex which

continually pulls the organization towards achieving TQM.

Finally, this research establishes a link between the soft system methodology and an

India specific cultural dimension called context sensitivity. The researcher argues that it is

because of context sensitivity of Indians that no resistance to change was found during ISO

implementation in Indian Railways. This also explains why post liberalisation Indians have

been able to make a mark in the world.

1

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Background to research

As a model of organisational change, TQM has been used in various forms for

decades (Yong & Wilkinson 2002). However, its success rate has not been very impressive

(Cao, Clarke & Lehany 2000; Tata & Prasad 1998). The reasons for its failures have

variously been summarised as:

(a) Improper understanding of the core concepts of TQM.

(b) Implementation was based on a one-size-fits-all assumption that is, it was

prescriptive and not participative (Boyne & Walker 2002; Korunka et al. 2003; Yusof &

Aspinwall 2000).

(c) Implementation of TQM ignored looking at different subsets of the organization

that is, it did not treat organization as a system (Reed, Lemak & Mero 2002).

TQM has also been criticised on the ground that it provides a rhetoric that is

individually interpreted and therefore carries inconsistent meaning across contexts (DeCock

1998; Zbracki reported by Reed, Lemak & Mero 2002).

The faltering success of TQM has led many researchers to establish relationships

between TQM and contextual factors such as culture (Lakhe & Mohanty 1994; Pun 2001;

Sahay & Walsham 1997), leadership (Rao, Raghunathan & Solis 1997; Zairi 2002),

teamwork (Eisenhardt & Tabrizi 1995; Quazi, Hong & Meng 2002) and training (Palo &

Padhi 2003). The personality profile of managers (Krumwiede & Lavelle 2000) and the host

country culture have been found to have a bearing on the adoption or success of TQM (Yen,

Krumwiede & Sheu 2002). Some researchers have looked at the specific problem of TQM

implementation in the public sector (Moon & Swafin-Smith 1998; Robertson & Seneviratne

1995; Stringham 2004; Yosuf & Aspinwall 2000) and tried to analyse whether TQM

implementation requires a different orientation in the public sector (Ehrenberg & Stupak

1994). Another stream of research has been conducted to arrive at empirically validated

factors that influence successful implementation of TQM (Black & Porter1996; Wali,

Deshmukh & Gupta 2003).

At a systemic level, a formal integration of TQM principles in a model of quality

management system has been attempted by ISO 9000: 2000 standard (Kartha 2002). Yet

2

there is a lack of reported research which establishes that ISO 9000:2000 certification enables

an organization to proceed on the TQM path. However, there is reported research about the

varying impact of ISO 9000: 1994 standard on an organization. It is both positive

(Escanciano, Fernndez & Vzquez 2001; Sun 1999) and negative (Curry & Kadasah 2002).

Some authors have tried to explain this varying impact on general factors such as country

culture (Noronha 2002); organisational factors such as intention behind certification

(Gotzamani & Tsiotras 2002; Poksinska, Dahlgaard & Antoni 2002); leadership (Hill, Hazlett

& Meegan 2001) and operational factors such as adoption of more than one enablers of TQM.

Therefore, there is a need to understand the implementation of TQM in terms of these

intervening factors.

Looking from this perspective, there seems to be a need to understand successful

implementation of TQM for organisational change as a function of the intra-organisational

parameters mentioned above.

1.2 Research problem

The above introductory background throws up the following broad research problem

which this thesis will address

Can TQM be used as the basis for organisational transformation? If yes, how can it

be effectively implemented in an Indian bureaucracy?

Within the Indian bureaucracy, this thesis will study the implementation related

issues in the context of Indian Railways which is the largest Indian bureaucracy.

The ISO 9000: 2000 model is the framework in which the study will be undertaken.

This is because ISO 9000: 2000 provides a change mechanism and change-monitoring model

which lends a holistic approach to change. The international standard organization claims

that its eight underlying principles are also in consonance with the tenets of TQM

(www.iso.org).

Thus this thesis attempts to understand whether the revised ISO 9000 standard is

designed for taking an organization on its TQM journey and how the intra-organisational

intervening variables of culture, presence of enablers of TQM and managements intention

behind certification affect this journey.

3

1.2.1 Research pathway

The specific research pathways which have been used to seek answer to the research

problem are now indicated.

The first area to be explored pertains to TQM. It attempts to answer the following

questions-

What is the state of TQM today? That is, starting from the principles of the founding

fathers of TQM, where does it stand today? What variations, if any, has it undergone? What

factors contribute to and what factors impede its successful implementation. These are dealt

with in section 2.2.1, 2.2.2 and 2.2.3.

Since the focus of this thesis is India, this research looks at different aspects of

Indian culture in their organisational context. How does Indian culture affect the

organisational values of Indian Railway personnel in the context of TQM? These are dealt

with in section 2.2.6.

Since Indian Railways is a bureaucratic organization, section 2.2.7 tries to explore

the core values of Indian bureaucracy and how it affects the organisational values and beliefs

of railway personnel who are part of this bureaucracy.

Other than establishing the status of TQM today and an understanding of the

organisational values and beliefs of Indian Railway personnel, the research also focuses on

the issues involved in the successful implementation, assimilation and continuance of TQM.

The key issues in the implementation of TQM are taken up in sections 2.2.5, 2.2.6 and 2.2.8

wherein the relationships between TQM and ISO, TQM and culture and TQM and

transformational leadership are dealt with.

Understanding these issues leads to the development of specific research questions:

What are and what should be the organisational policies and practices of Indian Railways

and what are the culturally induced values of Indian Railway personnel. The thesis also

assesses the general impact of ISO certification in Indian Railways. With TQM as the focus,

this research then takes up a participative style towards TQM implementation via the ISO

9000: 2000 route using an action research (AR) methodology. A question arises: does this

4

participative style build a learning capacity among the railway personnel? Answer to this

question is discussed at the end of the descriptions of the action research cycles.

1.2.2 Contribution

(i) At present there are very few AR based ISO 9000 implementations in the

government sector. So this thesis is expected to contribute to the literature by showing the

implementability of ISO 9000 in a government organization using a bottom-up approach.

(ii) In India, there has been very little work in the area of change management

through AR. Thus, to the Indian academic community, this will be one of the first studies of

systematic implementation of change using AR.

(iii) The contribution of this research to practice will be to the Indian organizations,

especially bureaucratic organizations. It will explain what flavour, if any, of TQM is suited

for bureaucracy and how its members internalise and implement the basic tenets of TQM.

1.3 J ustification for research

(i) The unimpressive success rate of TQM implementation in western countries,

inspite of it being around for more than 30 years in the field of research, has brought into

focus the contextual factors which mediate in the successful implementation of TQM and

also the route selected for TQM implementation. From this point of view, the values and

beliefs of the members of an organization provide a set of context for quality implementation.

(ii) Though the factors which lead to TQM are now understood, the current state of

research does not provide a synthesis of these factors. That is, there is little research carried

out which can explain the success or failure of TQM oriented change initiative in the light of

the totality of the understanding developed about TQM.

(iii) There are relatively few reported studies of TQM implementation with

organisational members as the focus that is, a bottom-up process involving the organisational

members in planning, implementing and evaluating the quality management system.

(iv) Internationally, TQM has generally been studied in the private sector

environment. There is not much evidence of research about its implementation in a

bureaucracy.

5

Another justification for the research comes from the need for change in the Indian

Railways.

1.3.1 Need to change for Indian Railways

The organisational justification for this study comes from the compelling need to

change for the Indian Railways made time and again (Sondhi n.d.). It needs to change in

order to survive. But given its history, how can a beginning be made for successful

implementation of change in Indian Railways. One option is to make an ambitious change

program, so ambitious, that it fundamentally alters the social system of Indian Railways. But

can the Indian Railways accommodate such a change programme? If the change is going to

fundamentally alter its social system, are the different stakeholders of Indian Railways the

government, the railway personnel and indeed, the customers of Indian Railways- the Indian

people - going to allow the implementation of such a radical change? It is worthwhile to

point out in this connection that in 1998, the Government of India appointed the Rakesh

Mohan committee to suggest ways for changing the Indian Railways. In its report, submitted

in the year 2001, the committee has inter alia mentioned that the Indian Railways is the most

studied organization in the world. However, hardly any one of the findings of those studies

has been implemented (quoted by Sondhi n.d). Not surprisingly, the recommendations of the

Rakesh Mohan committee too, were never implemented because it adversely affected all the

stakeholders. This is a pointer to the fact that while the malaise of Indian Railways and its

solutions from a purely large scale organisational transformation angle are well known, the

different stake holders of Indian Railways have ensured that such solutions remain

unimplemented.

The second option for change is to keep it at the level of window dressing. In this

case, the old systems remain untouched and they continue to generate the same behaviours.

However, the researcher believes that it is possible to bring about a change in a

manner and in such areas of Indian Railways which is acceptable to different stakeholders

and therefore implementable.

In the context of Indian Railways, action choices emanating from changes in such

factors as ownership and structure have the risk of antagonising the three important stake

holders - the government, the railway personnel and even the customers who would to see

the Indian Railways more as a not-for-profit organization. Thus it can make them withdraw

from or oppose the proposed change. However a change in such factors as system, culture,

6

leadership and industrial relations are not necessarily threatening to them and a beginning can

be made to initiate change in these areas.

Thus the intent of this research is to use TQM via the ISO 9000: 2000 route as the

overarching method for bringing about change in the Indian Railways

1.4 Methodology

Since this is perhaps the first doctoral level study on the Indian Railways, the overall

framework of research methodology is largely qualitative. Since the focus of the work is to

improve the intra-organisational processes within the Indian Railways, the concept of

customer here is that of an internal customer.

Literature review is the prime source for understanding the impact of Indian

bureaucracy and Indian culture on the values of Indian Railway personnel. The preliminary

literature review indicated that enough literature is available to understand the cultural values

of Indians. However, there is no direct study of the organisational values within the Indian

Railways. Thus direct assessment of the organisational values of Indian Railway personnel is

done. Established instruments are used for this assessment. The instruments have already

been extensively tested for their reliability and validity.

Literature review is the prime source for assessing the state of TQM and its status in

India.

A questionnaire-based survey of different units of Indian Railways is used to assess

the impact of ISO 9000 certification in these units.

It has been mentioned earlier that one of the weaknesses of TQM implementation has

been the prescriptive style which ignores the tacit factors (J oseph et al. 1999) which could

drive TQM success. Thus the emphasis of this research is to develop a bottom-up approach

of quality implementation. Therefore, action research (AR) methodology is used to

progressively implement the ISO 9000: 2000 quality system. For this purpose, an action

research model proposed by Perry and Sankaran (2002) is used.

1.5 Outline of this thesis

Chapter 2 is a literature review about the parent and immediate disciplines of this

research. It begins with organisational change and a historical account of TQM. In the

7

immediate discipline, the linkage between TQM and systems theory and identification of

critical success factors of TQM are dealt with. This leads to a discussion on different TQM

awards. Thereafter the linkage between TQM and ISO, and TQM and culture are discussed.

The discussion on TQM and culture leads to a discussion on bureaucratic culture and status

of TQM in bureaucratic organizations. A recurring theme in TQM implementation both in

private sector and bureaucracy is that of transformational leadership. Thus the critical role of

transformational leadership in TQM is the last part of literature review.

The literature review leads to the identification of gaps which need investigation.

Chapter 3 describes the research methodology used. It begins by framing the research

questions which need investigation. It then develops the research map for the research

questions. The research map divides the research in three stages.

Stage one consists of two surveys. Survey A seeks to find answers to the first

research question What are and what should be Indian Railways core values, style of

management, growth strategies, competitive strategies and changes in organisational

structure / management system so as to transform Indian Railways into an excellent

organization? Survey B assesses the impact of Indian culture on the organisational values

of the Indian Railway personnel by measuring their hierarchical tendencies. Section 3.4

discusses the specific surveys which are used.

Stage two seeks to find answers to the second and third research questions. These

research questions are

Research question ii - What is the impact of ISO implementation in Indian Railways?

Research question iii- To what extent has the implementation of ISO 9000 brought

about a TQM orientation in Indian Railways?

This involves development of a scale which can objectively measure the transition of

an ISO certified organization towards TQM.

Sections 3.5 and 3.6 discuss the specific surveys which were used to find answers to

these two research questions.

Chapter 4 deals with the data collection and data analysis for the above surveys.

Stage three seeks to find answers to the fourth and fifth research questions:

Research question iv - Will a bottom up methodology build learning capacity among

the railway personnel?

Research question v - How can the enablers of TQM be integrated in a model for

attaining TQM via the ISO framework?

8

Chapter 5 and chapter 6 discuss the action research methodology which was used to

find answer to the last two research questions.

Chapter 7 synthesises the findings and draws conclusions from the research. Chapter

8 is the researchers reflection on the entire thesis.

1.6 Limitations

The focus of the work is in the context of Indian Railways. The results obtained from

here can be applicable to the rest of the Indian Railways subject to further test. However, no

claim of generalisability can be made beyond that. For an outside customer, Indian Railways

is a service organization. But this study has been limited to the manufacturing section of

Indian Railways. This was done because TQM started in manufacturing sector and in the

Indian Railways also, its concept has largely been used in its manufacturing units via the ISO

9000 implementation.

1.7 My own value system as a researcher

When the researcher joined the Indian Railways, he found on the table of a railway

engineer, underneath a transparent glass sheet, a chart which read as

Error Punishment

Inspection not done Withhold annual increment in salary

Not reporting on time Decrease in grade of salary

J umping the signal Demotion

Accident Dismissal from service

When he checked up, it was explained that since there were so many cases of these

types of errors, to make the decision making simpler for the engineer, this chart came in

handy in deciding what level of punishment was required for different categories of errors.

Apparently the railway engineer was a robot who would mechanically hand over punishment!

The researcher wondered what happened to the staff who had made an error of other than an

accident? They obviously continued in the system, but at what level of efficiency?

9

Notwithstanding this managerial mind set, the researcher has always been impressed

by the fact that though close to 50% of its staff are illiterate, and it has only one engineer for

every 500 workers, Indian Railways manufactures, maintains and runs technologically

advance locomotives and coaches. Further, during the last 18 years, Indian Railways has

reduced its workforce by 300,000 without any formal voluntary retirement scheme or golden

handshake and there has not been a murmur of protest in the job scarce India. Yet he used to

hear You cannot do much in the Indian Railways. The politicians will not allow you to do.

The staff is not interested in working. This made him wonder whether the tendency for

external locus of control has been manifested in the working of Indian Railways. Thus in his

professional work, the researcher tended to stretch his subordinates and his superiors beyond

their conventional standard of working. To their credit, he did not find the subordinates

shirking in meeting the stretched expectations or the superiors and peers shirking in their

stretched assistance to him. This made the researcher undertake a formal study of Indian

Railways to get an academically validated study of this organization.

When the researcher started this research, the initial aim was to look for ways to bring

about improvement in the Indian Railways which was by and large acceptable to its

stakeholders and which was also implementable. TQM appeared to him one such way. He

thought he would do this by juxtaposing the basics of TQM on to the ground realities of

Indian Railways. As a student, his initial grounding has been in the field of mathematics.

Therefore he has always tried to get an unbiased estimate of the reality out there. However

after joining the service, as more and more varieties of reality began to unfold before him, he

began to realize the shortcoming of trying to get an unbiased estimate of reality. The situation

became more complex when he realized that in a social situation, even within one type of

reality, there were so many variables which interacted with each other that it was impossible

to isolate the impact of one variable from another. This showed to him the importance of

context in decision making. The context in decision-making became the boundary condition

within which a social system like an organization worked. This has been reflected in this

research also. Until chapter 4, this research is largely defining the boundary conditions of

Indian Railways.

Another major way this research differs from other research is that data as it emerges

during research has been compared with other emerging data or with existing literature. The

data has not been kept in isolation till the end when they will be compared with other data or

existing literature. This approach has made the research more focused without losing rigour

in the context in which the research was done. Thus there are cross comparisons to other

10

parts of literature in the literature review itself and research data have been compared with

earlier data as they emerge in later chapters of the thesis.

2.0 Conclusion

This chapter has provided an overview of the thesis. A synopsis of each

chapter of the thesis has been dealt with. A detailed description of each chapter now follows.

11

Chapter 2 Literature Review

Introduction

This research aims at studying TQM as a model for bringing about organisational

transformation in Indian Railways and identifying ways for effective implementation of that.

Thus the broad research question has been framed as follows:

Can TQM be used as a model for organisational transformation of Indian Railways?

If yes, how can it be effectively implemented in Indian Railways?

The purpose of this chapter is to carry out a literature search on TQM as a model of

change and understand the key issues involved in the implementation of TQM in Indian

Railways.

Concept map

Based on this question, the concept map for literature review is shown in Figure 2.1. The two

parent disciplines, organizational change and TQM are discussed in sections 2.1.1 and 2.1.2.

Their interaction has been discussed in sections 2.1.3 (TQM as a philosophy of change).

These form the basis for literature review of the immediate discipline wherein the

focus is on the interaction between different aspects of TQM. Different immediate disciplines

have been taken up as they naturally emerge during discussion. That is, the immediate

disciplines have not been taken based on any given a-priori set or point of view or school of

thought. Thus the flavour of the discussion is rather eclectic. Each major theme is also

reviewed in the Indian context so that the focus remains on the research question mentioned

earlier.

12

Figure 2. 1Concept map for literature review

Source: developed for this research.

2.2 Immediate discipline

2.2.1 TQM- a systems perspective

2.2.2 Critical Success Factors (CSFs) for TQM

2.2.3 Different international quality awards

2.2.4 Synthesis of system dynamics, CSFs and quality award

criteria

2.2.5 TQM and ISO

2.2.6 TQM and culture

2.2.7 Indian bureaucracy

2.2.8 TQM and transformational leadership

2.3 Summary of above and overview of

central problem

2.4 Identification of the gaps which need

investigation

Parent discipline 1

2.1.1Organisational change

Parent discipline 2

2.1.2 Total Quality Management

2.1.3 TQM as a philosophy of change

13

2.1 Parent discipline

2.1.1 Parent discipline 1-Organisational Change

Organisational change models closely parallel how organizations have been viewed

over time. From scientific management to organisational development and organisational

studies, the study of organization has moved from a study of mechanical functions from a

closed system perspective to a study of complex adaptive functions from an open system

perspective. Within open systems theory, contingency theory materialised as a means of

accounting for change within an organization. Contingency theory states that depending on

the level of turmoil within an organization, different systems theories should be adopted for

facilitating change. Thus in a government organization where stability and bureaucracy cause

change to occur slowly, a more mechanistic model should be adopted (McElyea 2003, p.63).

Within the field of organisational change, a comparison of the traditional change

model and complex adaptive model of organization change is shown in Table 2.1.

14

Traditional Models of Organisational

Change

Complex Adaptive Model of

Organisational Change

Few variables determine outcome

Innumerable variables determine outcome

The whole is equal to the sum of its parts

(reductionist)

The whole is different from the sum of its

parts

Direction is determined by design and power

of a few leaders

Direction is determined by emergence and

the participation of many people

Individual or system behaviour is knowable,

predictable and controllable

Individual or system behaviour is

unknowable, unpredictable and

uncontrollable

Causality is linear: every effect can be traced

back to a specific cause

Causality is mutual: every cause is also an

effect and every effect is a cause

Relationship are directive

Relationship are empowering

All systems are essentially the same

Each system is unique

Efficiency and reliability are measures of

value

Responsiveness to the environment is the

measure of value

Decisions are based on facts and data

Decisions are based on tensions and patterns

Leaders are experts and authorities Leaders are facilitators and supporters

Table 2. 1Traditional change model vs. complex adaptive change model

Source: McElyea (2003, p. 63).

Mastenbroek (1996) looks upon organisational change in historical perspective and

emphasises that organizational change is essentially a duality management, a balance

between autonomy and interdependence, between steering and self-organization. From this

perspective, strategies such as empowerment cannot be corrected without strong steering.

Top-down reengineering cannot be balanced without the responsibility and creativity of work

units. Mastenbroek says that TQM and continuous improvements often do not live up to their

promises because the line organization is involved in rather awkward ways. All kinds of

analysis and research, internal and external consultants obstruct the development of steering

and self-organization in the line organization. This impedes the cultural change necessary to

give continuous improvement momentum. Capacities for steering and self-organization are

critical assets for such a culture. It is to be noted that this approach does not ask for an

absolute participative management style, rather a balance between participative and directive

style. A similar view has also been expressed by Cunha, Cunha and Dahab (2002). They have

15

called for a dialectic synthesis between the soft and hard (yin and yang) side of

management to get a better look at TQM as shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2. 2The yin-yang of TQM

Source: Cunha, Cunha and Dahab (2002).

2.1.2 Parent discipline 2 Total Quality Management

2.1.2.1 Historical background

Today, TQM has become a part of corporate management on a global scale (Lakhe &

Mohanty 1994; Melan 1998; Yusof & Aspinwall 2000). Quality today is studied under the

overall umbrella of Total Quality Management. The improvements brought about by TQM

in the J apanese industry are too well known to merit repetition here. Quality as a concept has

moved from being an attribute of the product or service to encompass all the activities of an

organization.

The core philosophy of TQM as it is understood today is that each step in a

production process is seen as a relationship between a customer and a supplier (whether

internal or external to the organization). The suppliers will have to meet the customers

Norm

Standardization

Control

Methods

Statistics Participation

Inspection trust

Planning creativity

Top Down Leadership Suggestions

Quantity self-control

bottom up leaders

collaboration

democratic leadership

quality

autonomy

16

requirements, both stated and implied, at the lowest cost. Waste elimination and continuous

improvement are ongoing activities.

The early development of total quality management was influenced by a few quality

gurus: Deming, J uran, Feigenbaum, Crosby and Ishikawa. Their key contribuitions to the

quality movement will now be looked at.

The work of Deming: The main thesis of Deming is that by improving quality, it is possible

to increase productivity which results in improved competitiveness of a business enterprise.

According to Deming, low quality results in high cost which will lead to loss of competitive

position in the market. His approach can be summarised in his 14 point programme (Gaither

& Frazier 1999, p. 634):

(i) Create constancy of purpose for improvement of product and service.

(ii) Refuse to allow commonly accepted levels of delay for mistakes, defective material, defective

workmanship.

(iii) Cease dependence on mass inspection to achive quality.

(iv) Reduce the number of suppliers. Buy on statistical evidence, not price.

(v) Constantly and forever improve the system of costs, quality, productivity and service.

(vi) Institute modern methods of training on the job.

(vii) Focus supervision on helping people to do a better job.

(viii) Drive out fear.

(ix) Break down barriers between departments. Encourage problem solving through team work.

(x) Eliminate numerical goals slogans, posters for the workforce.

(xi) Use statistical methods for continuing improvement of quality and productivity and eliminate

work standards prescribing numerical quotas.

(xii) Remove barriers to pride of workmanship.

(xiii) Institute a vigorous program of education and training.

(xiv) Clearly define managements permanent commitment to quality and productivity.

From these initial concepts, Deming later developed what he called the system of

profound knowledge (Bauer, Reiner & Schamchale 2000, p.412). This means appreciation

of a system, knowledge about variation, theory of knowledge and psychology. Deming said

that only if the top management is able to understand the company as a complex system, are

they able to successfully improve the structures of the system ( Bauer, Reiner & Schamschule

2000, p.412).

The work of Juran : Unlike Deming whose approach was more process oriented, the ideas

of J uran were having a managerial flavour (Kruger 2001). His main contribution was that

17

quality control must be an integral part of the management function. This broadened the

understanding of quality. Visible leadership and personal involvement of top management is

important in inspiring quality across the organisation.

According to J uran (1988), to demonstrate commitment to quality the management

should establish a quality council which would coordinate the companys various activities

regarding quality. Further, the management should establish a quality policy which should

guide the managerial action. The management has to establish quality goals which should be

expressed in numbers and should have a time frame. Once a specific goal has been