Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Terapi Okupasi

Hochgeladen von

Nerz Yuhi0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

27 Ansichten9 Seitenjurnal keperawatan jiwa

Originaltitel

terapi okupasi

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenjurnal keperawatan jiwa

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

27 Ansichten9 SeitenTerapi Okupasi

Hochgeladen von

Nerz Yuhijurnal keperawatan jiwa

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 9

Clinical Rehabilitation

27(7) 638 645

The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0269215512473136

cre.sagepub.com

CLINICAL

REHABILITATION

473136CRE27710.1177/0269215512473136Clinical RehabilitationHoshii et al.

2013

1

Department of Rehabilitation Science, Kobe University

Graduate School of Health Sciences, Japan

2

Higashikakogawa Hospital, Japan

Subject-chosen activities in

occupational therapy for the

improvement of psychiatric

symptoms of inpatients

with chronic schizophrenia:

a controlled trial

Junko Hoshii

1

, Kayano Yotsumoto

1

, Eri Tatsumi

1

,

Chito Tanaka

1

, Takashi Mori

2

and Takeshi Hashimoto

1

Abstract

Objective: To compare the therapeutic effects of subject-chosen and therapist-chosen activities in

occupational therapy for inpatients with chronic schizophrenia.

Design: Prospective comparative study.

Setting: A psychiatric hospital in Japan.

Subjects: Fifty-nine patients with chronic schizophrenia who had been hospitalized for many years.

Interventions: The subjects received six-months occupational therapy, participating in either activities

of their choice (subject-chosen activity group, n = 30) or activities chosen by occupational therapists

based on treatment recommendations and patient consent (therapist-chosen activity group, n = 29).

Main measures: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and the Global Assessment of Functioning

(GAF) Scale were used to evaluate psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial function, respectively.

Results: After six-months occupational therapy, suspiciousness and hostility scores of the positive scale

and preoccupation scores of the general psychopathology scale significantly improved in the subject-

chosen activity group compared with the therapist-chosen activity group, with 2(2) (median (interquartile

range)) and 3(1.25), 2(1) and 2.5(1), and 2(1) and 3(1), respectively. There were no significant differences

in psychosocial functions between the two groups. In within-group comparisons before and after

occupational therapy, suspiciousness scores of the positive scale, preoccupation scores of the general

psychopathology scale, and psychosocial function significantly improved only in the subject-chosen activity

group, with 3(1) to 2(2), 3(1) to 2(1), and 40(9) to 40(16) respectively, but not in the therapist-chosen

activity group.

Article

Corresponding author:

Takeshi Hashimoto, Department of Rehabilitation Science,

Kobe University Graduate School of Health Sciences,

Tomogaoka 7-10-2, Suma-ku, Kobe 654-0142, Japan.

Email: hashimo@kobe-u.ac.jp

Hoshii et al. 639

Conclusions: The results suggested that the subject-chosen activities in occupational therapy could

improve the psychiatric symptoms, suspiciousness, and preoccupation of the inpatients with chronic

schizophrenia.

Keywords

Occupational therapy, client-centered, schizophrenia, controlled trial

Received: 16 April 2012; accepted: 9 December 2012

Introduction

Beginning in the 1960s, many countries began shift-

ing from a hospital-based system of mental health

treatment to one centered on the community. After

1980, the number of hospital beds and length of

hospital stays reduced sharply. In Organization for

Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

countries, the average length of stay in 2005 for

patients with schizophrenia was 38 days.

1

In con-

trast, the number of psychiatric beds in Japanese

hospitals increased suddenly in the 1960s, and the

average length of stay in 2008 for patients with

schizophrenia was 601 days.

2

Mental health care in

Japan has historically been hospital-centered, char-

acterized by long hospital stays and insufficient

support services to allow people with mental disor-

ders to live in the community.

3

Long-term hospitaliza-

tion can cause institutionalization.

4,5

Patients with

institutional syndrome restrain themselves, live a

passive life, and lose their individuality and initiative.

4,5

The 2009 interim report of Visions in Reform of

Mental Health and Medical Welfare noted that

patients with schizophrenia who had stayed in a

hospital for more than one year were more likely to

be subsequently hospitalized for a long period.

6

Some patients with schizophrenia continue to expe-

rience a chronic course of symptoms followed by

long-term hospitalization.

The symptoms of schizophrenia include positive

symptoms, negative symptoms, cognitive dysfunc-

tions, and nonspecific psychological symptoms, such

as anxiousness/depression.

7

Psychopharmacological

treatments, which are the basic treatment, are not

highly effective.

8,9

The effect of psychosocial

therapies, which are provided as add-on therapies

to psychopharmacological treatments, is also

insufficient.

9

Therefore, it is necessary to establish

an effective treatment that minimizes prolonged

hospitalizations and promotes the transfer of patients

back to the community.

Psychiatric rehabilitation, including occupational

therapy, has been a client-centered practice since

the 1990s.

1013

Corring et al.

10

emphasize that it is

important to focus on client perspectives. It is also

important for the clients to work on activities based

on their preferences and choices. Following the

introduction of client-centered occupational therapy

in Japan, it quickly became common in most psychi-

atric hospitals. However, little research has been

done studying the effects of client-centered occupa-

tional therapy in psychiatric hospitals in Japan.

The aim of this study was to compare the effects

of subject-chosen and therapist-chosen activities in

the occupational therapy on the psychiatric symp-

toms and psychosocial functions of patients with

schizophrenia.

The hospital ethics committee approved this

study on 19 January 2010.

Method

The study was conducted at a private psychiatric

hospital located in an urban area. We assessed all

inpatients for eligibility; 209 of them were diag-

nosed with schizophrenia, as defined by the

International Statistical Classification of Diseases

(10th Revision), and had been hospitalized for more

than a year as of January 2010. A total of 59 patients

were included in the study after excluding patients

who had difficulty communicating owing to their

640 Clinical Rehabilitation 27(7)

symptoms, those who were going to be discharged

in a few day, and those who declined to participate

in the study.

The allocation for males and females was inde-

pendent. Each male subjects data were consecu-

tively listed in a row on an excel spreadsheet. The

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale

scores were in the first column. All dates were

sorted according to the GAF score (from the high-

est to the lowest). Subjects on odd numbered rows

were allocated to a subject-chosen activity group

and those on even numbered rows were allocated

to a therapist-chosen activity group. The same pro-

cedure was followed for females. The data for

males and females were unified as a subject-chosen

group and a therapist-chosen group.

For the subject-chosen activity group, at the

first interview, the subjects were asked to choose

activities. The Canadian Occupational Performance

Measure (COPM)

14

was used in the process of

extraction of the chosen activities so that the occu-

pational therapists could understand the subjects

choices, regardless of their years of experience.

After subjects had determined the set of activities

that they would take part in, the subjects performed

these activities.

For the therapist-chosen activity group, the first

series of interviews was conducted without using

the COPM, and the occupational therapists chose

activities for patients based on treatment recom-

mendations. The therapists then had their patients

perform these activities under patients consent.

The therapist-chosen activity is often employed

in the occupational therapy for chronic inpatients

with severe symptoms of schizophrenia in Japan.

In both groups, when a patient completed the

first activity that had been chosen, the next activity

was chosen and performed via the same process.

Patients took part in occupational therapy for up to

two hours, once a week, for six months (March to

September 2010). The interviews and interven-

tions were conducted by different therapists so that

differences in the relationship between subjects

and occupational therapists owing to interview

methods could be avoided.

Psychiatric symptoms were measured using

the Japanese version of the Positive and Negative

Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

15

Psychosocial function

was measured using the Japanese version of the

GAF scale.

7

The GAF rates psychological, social,

and occupational function on a scale of 1 to 100.

7

To minimize evaluator bias, subject psychiatric

symptoms and psychosocial function was evaluated

before and after occupational therapy by a psy-

chiatrist who was blind to the group allocation of

patients.

The differences between the two groups in sub-

ject characteristics, including age of onset, amount

of drug, and duration (months) of occupational

therapy before the study, were examined using the

Student t-test. The other factors; age, duration of

illness, number of hospital admission, and length of

current stay were examined using the Mann-Whitney

U test, as the data were not normally distributed. For

the PANSS and GAF Scale, the differences before

and after the occupational therapies were tested

using the Mann-Whitney U test, and differences

within each group before and after the therapies

were tested using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

The statistical analyses were performed using

Statcel2 for excel 2007 (The Publisher OMS,

Saitama, Japan), and statistical significance was set

at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

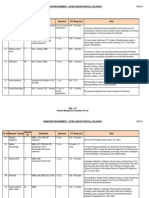

The flow of patients is shown in Figure 1. In each

group, one patient dropped out the study owing to

worsening symptoms. At the beginning of the study,

no significant differences were found between the

subject-chosen activity group and the therapist-

chosen activity group in any of the factors (Table 1).

Also, no significant differences in all item scores

of PANSS and GAF were demonstrated between

the two groups before the occupational therapies

(Table 2).

After the six-months occupational therapies,

suspiciousness and hostility scores of the positive

scale, and preoccupation scores of the general psy-

chopathology scale for the subject-chosen activity

group and therapist-chosen activity group were 2(2)

(median (interquartile range)) and 3(1.25), 2(1) and

2.5(1), and 2(1) and 3(1), respectively. The other

Hoshii et al. 641

items in PANSS and GAF Scores were not signifi-

cantly different between the two groups (Table 2).

These results show that the suspiciousness, hos-

tility, and preoccupation items were significantly

improved more in the subject-chosen activity group

as compared with the therapist-chosen activity

group (p < 0.05).

In the comparisons within the groups between

before and after the occupational therapies, the

scores in the suspiciousness item of the positive

scale and the preoccupation of the general psy-

chopathology scale were significantly improved

in the subject-chosen activity group from 3(1)

(median (interquartile range)) and 3(1) before the

occupational therapies to 2(2) and 2(1), respec-

tively, after the occupational therapies (p < 0.05).

In contrast, no significant changes were found for

any of the PANSS items in the therapist-chosen

group. The GAF Scores in the subject-chosen

activity group significantly improved after occu-

pational therapy, from 40(9) (median (interquar-

tile range)) to 40(16), respectively (p < 0.05).

This improvement was not found in the therapist-

chosen group.

Eligible for the study

(n = 209)

Excluded (n = 150)

scheduled for discharge in a few

days (n = 8)

difficulty communicating (n = 62)

declined to participate (n = 80)

Subject-chosen activity group

(n = 30)

Therapist-chosen activity group

(n = 29)

Received allocated intervention

(n = 30)

Received allocated intervention

(n = 29)

Loss (n=1)

drop-out for worsening

symptoms (n = 1)

Analyzed

(n = 28)

Analyzed

(n = 29)

Loss (n=1)

drop-out for worsening

symptoms (n = 1)

Consecutive alternative allocation by gender and GAF

(n = 59)

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

642 Clinical Rehabilitation 27(7)

Table 1. Characteristics of the patients in this study.

Subject-chosen activity Therapist-chosen activity p-value

(n = 29) (n = 28)

Gender male/female 14/15 14/14

Mean age (years)

a

57.1 9.8 55.9 10.5 n.s.

Age of onset (years)

b

23.6 8.5 24.3 8.0 n.s.

Duration of illness (years)

a

33.1 11.6 31.6 11.8 n.s.

Number of hospital admissions

a

5.4 4.3 4.5 2.9 n.s.

Length of current stay (months)

a

159.1 123.4 151.8 152.9 n.s.

Chlorpromazine equivalent (mg)

b

1329.3 851.8 1197.8 897.7 n.s.

Duration of occupational therapy

before this study (months)

b

97.2 46.2 75.3 57.1 n.s.

Mean SD; n.s., no significance.

a

Mann-Whitney U test.

b

Student t- test.

Table 2. Comparisons of PANSS and GAF scores between subject-chosen activity and therapist-chosen activity.

Sub-C (n = 29) The-C (n = 28) Difference

Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Sub-C The-C

Median (IQR) Two groups

a

Pre and post

b

Positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS)

Positive Scale

Delusion 4(2) 4(2) 3(2) 4(2.25) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Conceptual disorganization 4(1) 4(2) 4(1) 4(1.25) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Hallucinatory behavior 3(3) 3(2) 3.5(2) 4(2) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Excitement 3(1) 2(1) 3(1) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Grandiosity 2(2) 2(2) 3(1.25) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Suspiciousness 3(1) 2(2) 3(1.25) 3(1.25) n.s. p<0.05 p<0.05 n.s.

Hostility 2(1) 2(1) 3(1) 2.5(1) n.s. p<0.05 n.s. n.s.

Scale total 20(5) 19(8) 22.5(7.5) 21(8.25) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Negative Scale

Blunted affect 4(1) 3(1) 3(1) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Emotional withdrawal 3(1) 4(2) 3.5(1) 3.5(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Poor rapport 3(1) 3(2) 3(2) 3(0.5) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Passive apathetic social

withdrawal

3(2) 3(3) 3(1) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Difficulty in abstract thinking 3(2) 4(2) 3(1) 3(2) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Lack of spontaneity and flow

of conversation

3(1) 3(2) 3(2) 3(1.25) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Stereotyped thinking 3(1) 3(1) 3(0.25) 3(0.25) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Scale total 23(10) 25(11) 22(7) 23(8) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

General Psychopathology Scale

Somatic concern 2(1) 2(2) 3(2.25) 2(2) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Anxiety 2(1) 2(1) 3(1) 2(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

(Continued)

Hoshii et al. 643

Discussion

We adopted only the item that improved in both

group and prepost comparisons as an improvement

item. The subject-chosen activity in occupational

therapy consisted of patients choosing and per-

forming activities and being supported in perform-

ing it by occupational therapists. This might result

in improvements on the suspiciousness item of the

positive scale and the preoccupation item of the

general psychopathology scale of PANSS.

The suspiciousness item of the PANSS positive

scale is defined as unrealistic or exaggerated ideas of

persecution.

15

In the subject-chosen activity group,

the occupational therapists accepted the activities

that the subjects chose and coordinated the environ-

ments in order to support the subjects in performing

their activities satisfactorily. This relationship

between the subject and the occupational therapist is

called a partnership. This is one of the important

concepts constituting client-centered occupational

therapy.

1618

Partnership leads to the subjects trust in

their occupational therapists

16

and comfortable per-

formance of activities. This experience is considered

to relieve patient suspiciousness. This characteristic

symptom, which is often observed in the acute stage,

makes it difficult to attain stable and smooth human

relationships. Ikebuchi

19

also reported that schizo-

phrenia symptoms, such as hostility, excitement, and

suspiciousness, which destroy patients relationships

with those around them, could be factors that prevent

them from being discharged from the hospital.

Therefore, it is suggested that subject-chosen

activities improve psychiatric symptoms, such as

suspiciousness, making it easier to build a stable

relationship between inpatients with chronic schizo-

phrenia and their therapists, and helping patients

recover enough to return to the community.

The preoccupation item of the PANSS general

psychopathology scale refers to absorption with

internally generated thoughts and feelings and

an autistic experience. This comprehensive psy-

chopathological symptom, encompassing both

positive and negative symptoms, is detrimental to

Sub-C (n = 29) The-C (n = 28) Difference

Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Sub-C The-C

Median (IQR) Two groups

a

Pre and post

b

Guilt feeling 2(0) 2(1) 2(1) 2(0.25) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Tension 2(1) 2(2) 2(1.25) 2(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Mannerisms and posturing 2(1) 3(1) 3(1) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Depression 2(2) 2(2) 2(1) 2(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Motor retardation 2(2) 3(2) 3(1.25) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Uncooperativeness 3(1) 2(2) 3(2) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Unusual thought content 3(2) 3(1) 3.5(1) 3.5(2) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Disorientation 2(1) 2(2) 2(2) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Poor attention 3(1) 2(1) 3(2) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Lack of judgment and insight 4(2) 4(1) 4(2) 4(2) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Disturbance of volition 3(2) 3(2) 3(2) 3(2) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Poor impulse control 3(1) 3(1) 3(1) 3(1) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Preoccupation 3(1) 2(1) 3(1) 3(1) n.s. p<0.05 p<0.05 n.s.

Active social avoidance 3(1) 2(3) 3(1.25) 3(2) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Scale total 43(15) 43(18) 48(13.75) 42(17.25) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Global Assessment of

Functioning (GAF)

40(9) 40(16) 39(8.25) 37.5(6.75) n.s. n.s. p<0.05 n.s.

a

Comparison between two groups (Mann-Whitney U test).

b

Comparison between pre and post within group (Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Sub-C, subject-chosen activity group; The-C, therapist-chosen activity group; n.s., no significance.

Table 2. (Continued)

644 Clinical Rehabilitation 27(7)

reality orientation and adaptive behavior.

15

In the

subject-chosen activity group, the subjects chose and

performed activities with the support of occupational

therapists. Choosing and performing the activities

might enable the subjects, who are deeply involved

in an autistic experience, to act realistically and

autonomously, and might improve preoccupation of

the general psychopathological symptoms.

When they are experiencing strong suspicion,

patients with schizophrenia often avoid relationships

with others and their surroundings, and immerse

themselves in their own experiences. Therefore, the

results of this study also suggest the possibility that

the improvement of positive symptoms, such as

suspiciousness, may improve the preoccupation of

general psychopathological symptoms.

Negative symptoms improved neither in the ther-

apist-chosen nor subject-chosen activity groups.

This suggests that occupational therapy did not

directly improve the negative symptoms of schizo-

phrenia. This finding is consistent with the previous

finding that the negative symptoms of schizophrenia

are notoriously difficult to treat.

20

However, preoc-

cupation, the general psychopathological symptom

encompassing both positive and negative symptoms,

was improved in the subject-chosen activity group.

This finding suggests that clinical conditions associ-

ated with negative symptoms could be improved

through client-centered occupational therapy, even if

it were difficult to improve the negative symptoms

themselves.

Client-centered occupational therapy, in this study,

consisted of interviews and interventions. The inter-

view was conducted less than five times, for 10 min-

utes each. Since the total interview time was so short,

the authors suggest that the influence of the interview

itself can be ignored. Therefore, the effects of the

client-centered occupational therapy would be owing

to the client-centered approach regarding patient

choices and performance in occupational therapy.

In this study, social function was also explored

using the GAF Scale. There was a slight improve-

ment in GAF scores in the subject-chosen group,

while no difference in GAF score was observed

between the subject-chosen and therapist-chosen

activity groups. Improvement in PANSS items, such

as suspiciousness and preoccupation in the subject-

chosen group, might have partially affected the

psychological functioning area of the GAF Scale

and led to a slight improvement in GAF scores.

Our findings suggest that the subject-chosen

activity in the occupational therapy could improve

the psychiatric symptoms of the inpatients with

chronic schizophrenia. In the therapist-chosen activ-

ity group, no effect of the occupational therapy was

found for any examined items. These results suggest

the possibility that the subject-chosen activities in

the occupational therapy break the cycle of long-

term hospitalization of the patients with intractable

schizophrenia who experience failed therapies by

various types of professionals and have long-term

chronic conditions. Currently, an effective treatment

is necessary to help patients return to the commu-

nity. The effects of the client-centered occupational

therapy in this study can be highly significant.

This study was limited by the fact that it was only

conducted with a small group of subjects at one hos-

pital. Less than one-third of eligible participants actu-

ally took part in the study. In light of the fact that

many patients with schizophrenia had disease periods

of more than 30 years, and hospitalization periods of

more than 10 years, the intervention period may have

been too brief to be effective. The authors recom-

mend conducting future studies in this area using lon-

ger and more frequent intervention periods. Increasing

the number of subjects and the participating institu-

tions may contribute to the establishment of the

client-centered occupational therapy as an effective

treatment for inpatients with chronic schizophrenia.

Clinical messages

Client-centered occupational therapy in

which patients chose and performed activi-

ties with support of occupational therapists

was feasible for inpatients with chronic

schizophrenia.

Subject-chosen activities in the occupational

therapy were more effective in improving

the suspiciousness and preoccupation of

inpatients with chronic schizophrenia.

Further investigation of the effect of the

subject-chosen activity may contribute

to the establishment of the occupational

therapy as an effective treatment toward

inpatients with chronic schizophrenia.

Hoshii et al. 645

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all of the patients, occupa-

tional therapists, and psychiatrists who contributed to

the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Kobe University

Graduate School of Health Sciences research fund.

References

1. Organization for economic co-operation and development

(OECD). Mental health in OECD countries. Policy brief,

Paris, France, November 2008.

2. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Table 59 in the

first volume, Patient survey 2008. Statics and Information

Department, Ministers Secretariat, Ministry of Health,

Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, Japan, December 2009 (in

Japanese).

3. Kuno E and Asukai N. Efforts toward building a commu-

nity-based mental health system in Japan. Int J Law Psy-

chiatry 2000; 23: 361373.

4. Martin DV. Institutionalisation. Lancet 1955; 269: 1188

1190.

5. Johnstone EC, Owens DG, Gold A, et al. Institutionaliza-

tion and the defects of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1981;

139: 195203.

6. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. An

interim report of Visions in Reform of Mental Health and

Medical Welfare in 2009. Report, Tokyo Japan, September

2009 (in Japanese).

7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statisti-

cal manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington,

DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

8. Lindenmayer JP. Treatment refractory schizophrenia.

Psychiatr Q 2000; 71: 373384.

9. Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, et al. The

schizophrenia patient outcomes research team (PORT):

updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull

2010; 36: 94103.

10. Corring DJ and Cook JV. Client-centred care means that

I am a valued human being. Can J Occup Ther 1999; 66:

7182.

11. Legault E and Rebeiro KL. Occupation as means to men-

tal health: a single-case study. Am J Occup Ther 2001; 55:

9096.

12. Cook S, Chambers E and Coleman JH. Occupational ther-

apy for people with psychotic conditions in community

settings: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil

2009; 23: 4052.

13. Schindler VP. A client-centred, occupation-based occu-

pational therapy programme for adults with psychiatric

diagnoses. Occup Ther Int 2010; 17: 105112.

14. Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, et al. Canadian occu-

pational performance measure. 4th ed. Ottawa: CAOT

Publications ACE, 2005.

15. Kay SR, Fiszbein A and Opler LA. The positive and nega-

tive syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr

Bull 1987; 13: 261276.

16. Law M, Baptiste S and Mills J. Client-centred practice:

what does it mean and does it make a difference? Can J

Occup Ther 1995; 62: 250257.

17. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. Enabling

occupation: an occupational therapy perspective. Ottawa:

CAOT Publications ACE, 1997.

18. Sumsion T and Law M. A review of evidence on the

conceptual elements informing client-centred practice.

Can J Occup Ther 2006; 73: 153162.

19. Ikebuchi E, Satoh S and Anzai N. What impedes discharge

support for persons with schizophrenia in psychiatric hospi-

tals? Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 2008; 110: 10071022 (in

Japanese).

20. Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT Jr, et al. The

NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symp-

toms. Schizophr Bull 2006; 32: 214219.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without

permission.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Staffing Pattern FormulaDokument1 SeiteStaffing Pattern FormulaPb100% (5)

- ABG Interpretation Made EasyDokument5 SeitenABG Interpretation Made EasyChris Chan100% (2)

- Medical Audit Report Summary: Client InformationDokument1 SeiteMedical Audit Report Summary: Client InformationTomal HalderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prediction in Mimic 3 DataDokument8 SeitenPrediction in Mimic 3 DataUday GulghaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper - FinalDokument16 SeitenResearch Paper - Finalapi-455663099Noch keine Bewertungen

- Brent Hospital and Colleges IncorporatedDokument2 SeitenBrent Hospital and Colleges IncorporatedArnold Cavalida BucoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nama: Yudi Supriyadi NIM: MB1218049 Kelas: TK 3: Task Week 9#Dokument4 SeitenNama: Yudi Supriyadi NIM: MB1218049 Kelas: TK 3: Task Week 9#yudi supriyadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Care/Intensive Care Unit Experience Internal Medicine INM.M INM.S CourseDokument11 SeitenCritical Care/Intensive Care Unit Experience Internal Medicine INM.M INM.S CourseAmer Moh SarayrahNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5Dokument10 Seiten5John C. LewisNoch keine Bewertungen

- One Good Deed Deserves AnotherDokument3 SeitenOne Good Deed Deserves Anotherizti_azrah4981Noch keine Bewertungen

- Icp Member Handbook Il PDFDokument36 SeitenIcp Member Handbook Il PDFjohnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safety Culture AHRQDokument8 SeitenSafety Culture AHRQangga rizkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maternal Mortality in Osun StateDokument5 SeitenMaternal Mortality in Osun StateObafemi Kwame Amoo JrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flowchart OB WardDokument1 SeiteFlowchart OB WardISABELLA MARIE AGUILARNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Surgical NurseDokument8 SeitenJournal of Surgical NurseWahyu WeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manila Doctors Hospital vs. So Un Chua PDFDokument30 SeitenManila Doctors Hospital vs. So Un Chua PDFj0% (1)

- Family Satisfaction in The Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care Unit: Another Important Quality MeasureDokument5 SeitenFamily Satisfaction in The Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care Unit: Another Important Quality MeasureSeptiana ChimuzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Board ExamDokument13 SeitenNursing Board ExamKira100% (48)

- Observational Study of Safe Injection Practices in A Tertiary Care Teaching HospitalDokument5 SeitenObservational Study of Safe Injection Practices in A Tertiary Care Teaching HospitalMuhammad HaezarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recruitment Aadhar ClinicalDokument7 SeitenRecruitment Aadhar ClinicalVishram LomteNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2005 Magnetom Flash 1Dokument96 Seiten2005 Magnetom Flash 1Herick Savione100% (1)

- Community Health Nurse RolesDokument4 SeitenCommunity Health Nurse Rolescoy008Noch keine Bewertungen

- Appropriate of Hospital Market: Measures AreasDokument21 SeitenAppropriate of Hospital Market: Measures AreasMartin GoldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aegys Pro-MRI: MRI Safety-Four Zones For Dummies PDFDokument3 SeitenAegys Pro-MRI: MRI Safety-Four Zones For Dummies PDFaegysabetterwayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Best Practice of Hospital Management Strategy To Thrive in The National Health Insurance EraDokument14 SeitenBest Practice of Hospital Management Strategy To Thrive in The National Health Insurance EraPuttryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter of Complaint To Massachusetts Department of Public HealthDokument4 SeitenLetter of Complaint To Massachusetts Department of Public HealthGreg SaulmonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class Action Petition 081919Dokument8 SeitenClass Action Petition 081919GazetteonlineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cad Cam Bar and MagnetsDokument5 SeitenCad Cam Bar and MagnetsAnnaAffandieNoch keine Bewertungen

- QDokument17 SeitenQFarhana KanakanNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparative Study of The Tea Sector in KenyaDokument49 SeitenA Comparative Study of The Tea Sector in KenyaAli ArsalanNoch keine Bewertungen