Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1 s2.0 S0261517796001161 Main

Hochgeladen von

Shoaib ZaheerOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1 s2.0 S0261517796001161 Main

Hochgeladen von

Shoaib ZaheerCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Pergamon

PII: S0261-5177(96)00116-1

Tourism Management, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 149-158, 1997

1997 Elsevier Science Ltd

All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain

0261-5177/97 $17.00 + 0.00

Atti tudes to careers in touri sm:

an Angl o Greek compari son

David Airey

School of Managerial Studies, University of Surrey, Guildford GU2 5XH

Athanassios Frontistis

Effective Management International, Vassiliadou 13, GR-111 41 Athens, Greece

Drawing on findings which form part of a wider study this article presents comparative

information on attitudes of young people in Greece and the UK about tourism as a sector for

their careers. It sets out the context within which career decisions are formed. It examines

perceptions of tourism and attitudes to tourism jobs. It suggests t hat the UK pupils have a

bet t er established careers support system and t hat they have a less positive attitude toward

tourism than their Greek counterparts apparently due to a more realistic view of the nature

of the jobs in question. It also points to a variety of perceptions about what constitutes a

tourism job, notably t hat many components of accommodati on and catering are not seen as

being part of tourism. It also demonstrates a difference between attitudes toward individual

tourism jobs and attitudes toward employment in the tourism sector as a whole. 1997

Elsevier Science Lt d

Keywords: t ouri sm jobs, at t i t udes to careers in tourism, careers support, identification of t ouri sm jobs

The relationship bet ween tourism and the workforce

can be examined from a number of different points

of view. Some of these have been well explored over

a relatively long period. For example, the employ-

ment creation effects of tourism, and education and

training for tourism have been document ed since

the mid-1960s. ',2 Similarly, although starting from a

rat her later date, t here is now a substantial litera-

ture about the nature and characteristics of tourism

empl oyment and careers. Mathieson and WalP

provide an early summary. One area which has

received much less attention is the perceptions and

attitudes of young peopl e to careers in tourism.

Ross 4 makes the point forcefully that ' Relatively

little research has thus far been conduct ed on the

perceptions and intentions of those individuals who

are likely to ent er the tourism/hospitality workforce' .

In some ways, given the i mport ance of the

workforce to the successful devel opment of tourism,

and given anecdotal evidence that attitudes to

tourism careers span such a wide range from

glamorous and exciting to poorly paid and mundane,

this lack of attention is surprising. But apart from

pioneering work by Ross 4-7 t here are few ot her

studies of this i mport ant relationship.

The early work by Ross ~ suggests that secondary

school students in Australia had a high level of

interest in management positions in the tourism and

hospitality industry and that they were prepared to

undert ake vocational preparat i on to achieve such

positions. He also found ~ that school leavers inter-

ested in hospitality and tourism positions generally

placed a higher than average value on achievement

in their planned professional life. In ot her words

tourism is potentially attracting the higher achievers.

In his later study of post-school intentions regarding

tourism and hospitality industry empl oyment in an

Australian tourism resort Ross 4 found that ' most

respondent s were highly interested in empl oyment

and perhaps a career in the tourism/hospitality

industry. Relatively few evinced no tourism and

hospitality empl oyment interest' . He went on to

suggest the possibility that ' the tourism/hospitality

industry is now regarded as holding considerable

promise for future empl oyment and careers

prospects in many western countries such as

149

Attitudes to careers in tourism: D Airey and A Frontistis

Australia' . Although, as he acknowledges, the level

of interest is influenced by the fact that familiarity

and involvement with the industry, which may be

high for many residents in such a tourism resort,

may lead to more favourable evaluations than would

be found elsewhere. This point is also made by

Murphy2

Positive attitudes toward tourism empl oyment

have also been found by Choy"' in Hawaii who,

noting that food and beverage is the major source of

employment, comment ed that the large majority of

tourism industry workers were satisfied with their

jobs and that a substantial proport i on would

encourage their ' bright' child to study tourism

industry management. He points out that this

reflects a positive attitude toward careers in the

tourism industry and that a significant proport i on of

respondents working in non tourism industry jobs

also held positive attitudes toward careers in the

tourism industry. In the UK Purcell and Quinn '~

indicated in their study of hotel and catering gradu-

ates that positive experience and perceptions of the

hospitality industry were main reasons for being

attracted to study hospitality management .

These positive attitudes contrast with ot her work

which identifies important concerns about employ-

ment in tourism. In his study of human resource

factors in tourism policy formulation, Baum ~2 identi-

fied a number of concerns by Chief Officers of

NTO' s of which the poor image of the tourism

industry as an empl oyer ranked of prime concern.

As Baum indicates this is a perception that is voiced

frequently but fails to recognize the diversity of

empl oyment within the industry. It is probable that

this response to a great extent reflects the situation

in the accommodat i on and food-related sectors,

especially with respect to small business. Koko and

Guerri er ~3 comment on jobs in the hospitality

industry being criticized for being 'physicallly repeti-

tive, poorly paid, controlled by task-oriented

managers and providing limited opportunities for

participation and development' . This unease about

tourism empl oyment is reflected elsewhere including

some careers literature which comment s on long

hours and poor pay. '4

In his study in the Spey Valley in Scotland, Get z '~

found that the hotel and catering sector was a

relatively unattractive option. Also comparing 1978

and 1992 he found that the desire to pursue a career

in hotel and catering empl oyment had dropped by

over one half. The percent age who agreed that ' jobs

in hotel and tourist establishments are attractive and

good for young peopl e' fell from 43 to 29% between

1978 and 1992. This is in a region where, in 1992,

42% of respondent s had a parent working in the

tourism industry and a high proport i on of respon-

dents had had direct experience working in the

industry.

Against this background, and with support from

the Commission of the European Communities

(CEC) a comparative study of Greece and the UK

was carried out in the first half of 1995 into the

views of young people about careers in tourism.

Ultimately the main goal of the study was to identify

and test ways of familiarizing young people in

Greece with working in tourism. The study drew

upon the experience of Greece and the UK and in

the process provided comparative information not

only about the attitudes of the young people but

also about the context within which these attitudes

are formed. The purpose of this paper is to set out

some of the key findings from the study as they

relate to the ways in which young people, in the two

countries, view tourism as a potential sector for

their careers.

Met hod

The first part of the study was a broad comparison,

mainly from secondary sources, but supplemented

by interviews with leading employers, of the scale

and scope of the tourism industry, of the systems of

education and training, including that concerned

with tourism, of careers guidance, and of likely

developments in the tourism industry and associated

careers.

This was followed by separate focus groups, of

about ten each, of pupils, parents and teachers,

conduct ed at three secondary schools in each

country, from Athens in Greece and from

Nottingham in the UK. Apart from providing infor-

mation about views of tourism, about careers and

about careers guidance, information from these

groups was also used to develop the questionnaire

for the later stages of the study. The focus groups in

each country were led by experienced careers

advisers. Each group followed a common format,

with appropri at e variations for the pupils, teachers

and parents, and they included a range of questions

and exercises, with prompts provided as required.

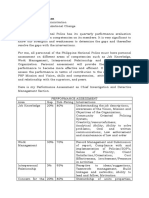

Figure 1 provides a summary of the content of the

focus group discussions with the pupils.

The subsequent questionnaire, which used infor-

mation from the focus groups, also followed a

common format in each country, although some of

the questions, particularly those relating to careers,

were different to reflect the different situations in

the two countries. The questionnaire was admini-

stered to 176 pupils in four schools in the

Nottingham area in May and early June 1995 and

152 pupils in t hree schools in the Gr eat er Athens

area in mid-April and early May 1995. No pupils

participating in the focus groups were included in

those responding to the questionnaire. In the UK

the 176 pupils represent ed about 15% of the total

cohort of the four schools. In Greece the 152 pupils

represent ed about 60% of the cohort. In both cases,

selection of the samples was in the hands of the

150

t eacher s and was cons t r ai ned by pupi l avai l abi l i t y

dur i ng t i met abl ed hours.

The school s in t he Not t i ngham ar ea i ncl uded one

in an i ndust r i al t own t o t he nor t h of Not t i ngham

wher e t her e is hi gh unempl oyment . The ot her s ar e

l ocat ed in t he city of Not t i ngham in mor e

pr os per ous ar eas wher e t her e is a hi gher pr opor t i on

of r esi dent s in pr of essi onal occupat i ons. The t hr ee

school s in Gr e e c e wer e in t he Gr e a t e r At hens

r egi on. Thes e wer e l ocat ed in di f f er ent par t s of t he

regi on; t he cat chment ar eas of t wo ar e r el at i vel y

Attitudes to careers in tourism: D Airey and A Frontistis

pr os per ous whi l e t he t hi r d dr aws f r om a less

pr os per ous di st ri ct . Al l t hr ee school s ar e publ i c

l yceums, whi ch account for ar ound 85% of all pupi l s

at this level. Pupi l s ar e r equi r ed to ent er t he l yceum

in t he ar ea in whi ch t hey live, t her e is no el ement of

sel ect i vi t y.

One of t he school s in t he UK was a si xt h-form

col l ege whi ch onl y has pupi l s in t he age r ange

16- 18. The ot her s t ake all age pupi l s and across t he

ful l -abi l i t y range. Wi t h t he except i on of t he sixth-

f or m col l ege, t he ot her pupi l s wer e all in t he age

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

I0.

QUESTION ACTIVITY/OUTCOME

Tell me about your ideal job

Have any of you decided what you are

going to do when you leave school?

Which of given named jobs do you

think are in tourism?

What do you think of 3 named jobs

in tourism?

Open discussion

Result on flip chart

Record Yes/No

Careers mentioned

39jobs given on lists,

Participants underline tourism jobs

leading to discussion

Guided discussion to elicit response

on status, level of skills, level of pay,

job security and others

How would you describe the people who

do these jobs?

Which career areas are you interested/

not interested in?

Which word best describes the people

who work in these areas?

Open discussion

14 career areas

(eg. Teaching, Army, Law, Tourism)

provided on list, participants record

answers on paper

Participants choose from well-paid, male

fun-loving, female, outgoing, boring,

How do you feel about a job in tourism?

What information have you received

about careers? What extra information

would you like?

How would you like to get extra

information?

strong, serious, clever, ordinary, badly

paid, want job for life.

Participants put choice on scale

from 0 (negative) to 100 (positive)

Discuss and record answer on

flip chart

Discuss and record answers on

flip chart

Figure 1 Summary of guide to focus groups (pupils)

151

Attitudes to careers in tourism: D Airey and A Frontistis

range of 14-16 years. Those from the sixth-form

college were in the age range of 16-18 years. In the

UK group, one of the secondary schools and the

sixth-form college included tourism as a subject of

study. Such a subject does not exist at school level in

Greece. Although it is difficult to make precise

compari sons, the soci o-economi c profile of the

pupils compl et i ng the questionnaires in the two

countries, as measured by parent al occupations, was

similar and the sex bal ance was also similar. The

questionnaires were i mpl ement ed in class time with

a member of the study t eam on hand to answer

questions and provide assistance as required.

In answering the questionnaire the pupils were

asked to provi de demographic variables such as sex,

occupat i on of parent s as well as personal interests;

i nformat i on about career plans, job preferences and

careers advice; and about views and attitudes to

employment in tourism. These views and attitudes

were examined in four separat e sets of questions.

(1) General attitudes to tourism empl oyment were

tested by the accept ance or rejection of four

st at ement s giving descriptions of empl oyment in

tourism. These st at ement s are given in Figure 2.

(2) These attitudes were furt her tested by the evalu-

ation of st at ement s concerning the nat ure of

jobs in tourism. A summary version of these

st at ement s is given in Table 6.

(3) As to what is recognized as a t ouri sm job, this

was tested by respondent s being asked to

classify different jobs according to whet her they

t hought the job bel onged to the t ouri sm sector.

A list of jobs is given in Table 7.

(4) Finally the respondent s were asked to indicate

in which of the identified tourism jobs they

would be interested as a career.

In the final part of the study, the groups of the

Gr eek pupils were exposed to one of three different

techniques of providing careers advice. These were

devel oped on the basis of the focus group discus-

sions and also recognized what is feasible in the

context of the education system in Greece. The first

group simply received a Touri sm Career Gui de

which had been prepared for the study. This was

handed out to the pupils who were asked to read it

during class time and at home. The second group

received the Touri sm Career Gui de one week

before a 1 hour lesson dealing with careers informa-

tion. During the lesson the t eacher explained the

contents of the guide and answered questions. The

final group received a 1 hour present at i on by a

tourism specialist with visual aids and the Touri sm

Career Gui de was handed out at the end of the

session. Aft er these activities the pupils were again

asked about their views and attitudes to empl oyment

in tourism using the same four questions to which

they had already responded.

Context

In order to underst and and interpret the results

of the study a number of similarities and differences

in the contextual background to tourism careers in

Gr eece and the UK were identified. The most

i mport ant of these were:

Tourism provides good career opportunities leading to well paid and exciting positions.

Working in tourism offers the chance to meet interesting people in a glamorous

environment. The work is very varied and gives the prospect of international travel.

Tourism is a growing industry which provides plenty of opportunities at many levels. The

work in tourism can be varied and interesting. There are good career opportunities for

those who work hard and like meeting other people.

Tourism offers opportunities at many levels and provides career prospects for those who

are prepared to accept hard work sometimes for low pay and with unsociable hours.

Career prospects in tourism are limited. Much of the work includes serving other people

and a lot of boring routine. It is usually badly paid. Many jobs have a low status and some are

only available on a seasonal basis.

Figure 2 Descriptions of employment in tourism

152

Attitudes to careers in tourism: D Airey and A Frontistis

Table 1 Career decision

UK Greece

(%) (%)

I know exactly what sort of career I want when I leave school.

I have not yet made up my mind. There are several things I might like to do for a career.

I have no idea what I want to do yet. There is plenty of time to decide.

Total sample

29 24

62 65

9 11

176 152

Tourism and employment

In both countries, accommodat i on, catering and

rel at ed services is the biggest sector of tourism

empl oyment , accounting for about 50% of the

total;

Touri sm accounts for about 5% of empl oyment in

the UK while in Gr eece the equivalent figure

reaches up to 15% during the seasonal peak

period;

In bot h countries t here has been a steady growth

in empl oyment in tourism;

Part -t i me work in tourism is much less common in

Gr eece than in the UK;

Seasonality of t ouri sm empl oyment is more

pr onounced in Gr eece than in the UK;

Education and training

Compul sory schooling in Gr eece is up to age 15,

in the UK it is up to age 16;

While in bot h countries, after compul sory

schooling, the pupils may follow a number of

clearly defined routes, the UK system offers

relatively mor e flexibility in allowing transfer from

rout e to route. Decisions t aken by 15 and 16 year

old Gr eek children are far mor e irreversible;

The ' world of work' plays a far mor e i mport ant

role in the compul sory educat i on system of the

UK than it does in Greece;

The UK has a well devel oped educat i on and

training system for t ouri sm with a br oad range of

courses and qualifications at all levels from

pre-vocat i onal courses in schools to graduat e and

post graduat e studies in universities. In Gr eece the

system is much less fully devel oped and tourism

studies do not exist at university level.

Careers education and guidance

The careers educat i on and guidance system is

much mor e fully devel oped in the UK than it is in

Greece;

The careers service in the UK has much closer

links with industry t han the equivalent in Greece;

A peri od of work experi ence during compul sory

school is common in the UK. It is almost

unknown in Greece.

Re s ul t s

Tables 1- 4 set out some of the background findings

from the study. Tables 5- 8 give i nformat i on about

attitudes to t ouri sm empl oyment in the two

countries. And finally Table 9 sets out the ' before

and aft er' views of the Gr eek pupils who experi-

enced the different kinds of careers advice.

Background findings

There are some similarities as well as some marked

differences bet ween the UK and Gr eek groups of

pupils in their views about careers. In each case, as

shown in Table 1, about 25% said that they had a

clear idea of the sort of career they wished to

pursue and about 10% indicated that they had no

idea about their future career. Within these figures

t here were some differences bet ween the sexes with

rat her mor e UK girls than boys having a clear idea

of their career (33% as against 23%) and bet ween

soci o-economi c groups. This may be because those

who perceive fewer choices have a cl earer idea of

their future. In the UK the lower socio-economic

groups expressed great er certainty with 45% saying

that they knew exactly the sort of career they

wanted. On the ot her hand in Gr eece it was the

upper soci o-economi c groups who appeared to be

mor e certain at 36%. While these figures give some

guide to career intentions they need to be t reat ed

with caution. This is particularly so for the Gr eek

figures. Asked later about the j ob they want ed to do,

only 14% of the Gr eek pupils, who said they knew

exactly what career they wanted, named just one job.

The ot hers showed a preference for a range of

different jobs. The same figure for the UK pupils

was 41%. This tends to suggest that the Gr eek

pupils may be at an earlier stage in their thinking,

and possibly less knowl edgeabl e than their UK

count er parts.

Faced with a list of jobs grouped into broad

categories, the pupils were asked to indicate those

they would like to do and of these which would be

their preferred choice. Scope was provided for t hem

to add to the list. The results of this are given in

Table 2. The Gr eek pupils gave an average of 4.4

different choices with the British at 3.9. The overall

picture reveals a stronger preference by the Greeks

for professional, business and management careers

and a stronger preference by the British for self-

empl oyment , i ndependent and ot her career areas.

Also a far higher proport i on of the British pupils

was not able to give a preferred choice. The fact

that 11% of Gr eek pupils said they had no idea

about their career choice, as shown in Table 1, while

153

Attitudes to careers in tourism: D Airey and A Frontistis

Table 2 Career preference

Career group

UK Greece

Preferred All Preferred All

Choice Choices Choi ce Choices

(%) (%) (%) (%)

Professional (doctor, lawyer etc.)

Busi ness & management

Public sector (including teaching)

Empl oyee, craft smen, unskilled workers

Self employed, i ndependent and ot her

Do not know

Number of respondent s

Average number of choices

Number of non-responses

Total sampl e

10 15 30 22

11 22 19 21

23 14 25 18

18 21 14 25

21 27 12 13

18 1

162 630 152 673

3.9 4.4

14 0

176 152

only 1% were unable to give a preferred choice

when given a list of jobs, provides furt her support to

the relatively fluid state of the decisions in that

country.

The source of careers advice as shown in Table 3,

reveals a marked difference bet ween Gr eece and the

UK. The careers guidance specialists (careers

officers, librarians and teachers) and work experi-

ence figure mor e promi nent l y among the responses

by the young peopl e in the UK. In Greece, possibly

because of a lack of ot her non-parent al guidance,

nearly half the pupils said that their career decision

so far was simply made on their own. Perhaps not

surprisingly, therefore, as shown in Table 4, the UK

Table 3 Career guidance and advice

UK Greece

(%) (%)

Parent s 28 30

Careers officer/librarian/teacher 19 11

Friends 12 9

Wor k experience 20 0

Own decision 6 49

Ot her 5 0

Do not know 11 1

Number of respondent s 157 149

Number of non-responses 19 3

Tot al sampl e 176 152

Table 4 Satisfaction with careers advice

UK Greece

(%) (%)

Fully satisfactory 13 7

Satisfactory 52 39

Very unsatisfactory 35 53

Number of respondent s 174 152

Number of non-responses 2 0

Total sampl e 176 152

pupils were far more satisfied with the careers

advice they had received.

Perhaps the most i mport ant issues from these

background findings are that with a bet t er

devel oped system for careers support and with a

relatively more flexible educational process the UK

pupils have a broader and possibly more realistic

view of career opportunities. The Gr eek pupils

operat i ng in a highly structured education system,

which itself has its sights set on university entrance,

have high career aspirations which are likely in any

case to be unrealistic and which for many will be

unachievable. The UK pupils at a similar stage are

more fully and broadl y advised, they are aware of a

wider range of options and their schools are less

' university focused' . As a result the career prefer-

ences, given in Table 2, including the high propor-

tion who ' do not know' may be more realistic.

Tourism and tourism careers

The pupils in bot h countries were present ed with

four st at ement s about empl oyment in tourism and

asked to indicate with which they most strongly

agreed and disagreed. The four st at ement s and the

overall summary of the responses are given in Table

5. These indicate an ambi val ent attitude by the UK

pupils which contrasts with the very positive view of

the Greeks. Ther e are a number of factors which

might explain this difference. Empl oyment in

Table 5 Attitudes about touri sm empl oyment

UK Greece

(%) (%)

Positive at t i t ude (agree 1 & 2, disagree 3 & 4)

Negative at t i t ude (disagree 1 & 2, agree 3 & 4)

Uncert ai n (ot her combi nat i ons including no answer)

Total sampl e

46 83

21 7

33 11

176 152

Comment on Chi -square test: There is a st rong difference

bet ween UK and Greece (Z ~ =53. 750, c~<0.00). Compari ng the

observed frequenci es with the normally expected distribution we

find UK: Z 2 9.48, ~<0. 008 GR: X 2 110.91, ct<0.000. This implies

that t he results are strongly significant.

154

tourism in Greece at 15% of the total is relatively

more i mport ant than in the UK where it accounts

for about 5%. The UK pupils have much great er

experience in tourism as consumers and hence may

have different perceptions of the glamour of tourism

employment. For example 88% of the UK pupils

had travelled internationally compared with 38% of

the Greeks. Also the relatively unrealistic view of

the Greek pupils about careers might from a part of

the explanation. But whatever the case, a figure of

fewer than 50% of UK pupils having a positive

attitude about empl oyment in tourism provides an

interesting message which deserves furt her

examination.

These views about tourism empl oyment were

explored furt her by asking pupils to indicate the

extent of their agreement to a number of state-

ments. A list of some of the statements with the

results are given in Table 6. Although the differences

between the pupils in the two countries are less

pronounced, these t end to confirm the generally

more favourable attitude of the Greek pupils toward

tourism and tourism careers.

In order to throw light on the pupils' perceptions

of what constituted a tourism job they were asked to

identify, from a list of jobs, which ones they felt

were in the tourism industry. The results, given in

Table 7, provide some interesting messages and

comparisons. The rest aurant sector, including chefs,

waiter/esses and rest aurant owners have a relatively

low level of identification as tourism jobs, as do

leisure managers and hotel housekeepers. Given the

i mport ance of the accommodat i on and catering

sector in total tourism empl oyment , about 50% in

both countries, this perception of young peopl e is an

interesting one. Among the differences between the

two countries is that among the Gr eek pupils airline

pilots and check-in staff have a low level of identi-

fication as tourism jobs while in the UK their identi-

Table 6 Statements about touri sm and touri sm careers

Attitudes to careers in tourism: D Airey and A Frontistis

fication level is very high. It is possible to speculate

that this results from the high proport i on of UK

pupils who have travelled abroad, mostly by air,

which points up the role of the airline sector in

tourism.

Of the jobs which they identified as tourism jobs

the pupils in the two countries were asked to

indicate the extent to which they were interested in

one or more of the jobs. As shown in Table 8 the

overall response by the Greek and UK pupils was

similar. About 60% were interested in at least one

tourism job and only about 10% categorically

rejected tourism jobs. It is interesting to compare

these results with those in Table 5. The effect of

asking about particular jobs, rather than about

tourism empl oyment generally seems to encourage a

more positive attitude by the UK pupils and a less

positive attitude by the Greek pupils. This may be

explained in part by a difference in the identification

of different jobs as belonging in the tourism industry

and a strong interest by the UK pupils in some of

these jobs. This is particularly the case for the

airline industry and for jobs as a hotel manager,

restaurant owner and ski instructor. The UK pupils

were more likely to identify jobs with airlines and as

a ski instructor as being a part of tourism and to

express a strong interest in such jobs. For jobs as a

hotel manager or restaurant owner they were more

strongly interested in such jobs than their Greek

counterparts even though the level of identification

of such jobs as being part of tourism was similar in

both countries. For a range of ot her jobs, such as

hotel receptionist, tourist guide, tourist information

officer, the level of interest by the UK pupils was

much lower than that expressed by the Greek pupils.

Changes in attitudes

In the final part of the study an attempt was made

to examine shifts in attitudes by the Greek pupils

Bri ef summary of statements

UK

Average

score*

Greece

Average

score* F-test

Positive statements

Int erest i ng job opport uni t i es

Can be st udi ed at university level

Well paid, manageri al opport uni t i es early in career

Chances for travel

Most i mport ant sector of economy

Growi ng sector

Negative statements

Unsoci abl e hours

Boring j obs

For t hose wi t hout hi gher educat i on

Low level poorly paid j obs

Most j obs seasonal

Much unempl oyment

Total sampl e

2.92

2.38

3.54

2.39

3.90

2.66

3.36

4.19

4.21

4.00

3.09

4.11

176

2.33

2.62

2.92

2.24

2.14

2.03

3.34

4.49

3.73

4.77

2.87

4.90

152

23.400

3.090

20.486

1.084

150.920

27.083

0.019

3.205

8.867

33.582

1.775

43.329

0.0000

0.080

0.0000

0.2987

0.0000

0.0000

0.8911

0.074

0.003

0.0000

0.184

0.0000

Note: *Averages calculated on 6 poi nt scale 1 = totally agree, 6 = totally diagree.

155

Attitudes to careers in tourism: D Airey and A Frontistis

following exposure to one of t hree different careers

information sessions. The results are given in Table

9. It is difficult to draw firm conclusions from this

because the majority of the results were not statis-

tically significant. Ther e was a general increase in

the level of identification of most jobs as being a

part of tourism. This was notably true and statis-

tically significant for the airline industry and hotels.

The rejection of food production and service as

forming a part of tourism remai ned clear.

Table 7 Identification of touri sm jobs

UK Greece

(%)* (%)*

Hotel manager 80 84

Hotel receptionist 58 72

Hotel housekeeper 44 47

Restaurant chef 30 21

Waiter/ess 27 31

Restaurant owner 37 28

Airline pilot 81 38

Officer on cruiseliner 85 69

Coach driver 62 50

Airline steward/ess 85 65

Airline check-in staff 71 15

Taxi driver 36 14

Tourist police officer 78 80

Tourist information officer 96 89

Tourist guide 98 92

Travel agent 91 77

Leisure centre manager 40 43

Ski instructor/monitor 64 37

Translator 74 49

Number of respondents 162 151

Number of non-respondents 14 1

Total sample 176 152

Note." *Percentage who agreed that the ' Job is definitely in the

tourism industry'.

Table 9 Identification and interest in touri sm jobs by Greek pupi l s

In the same way the shifts in the level of interest

in tourism jobs were also generally positive although

only the shifts related to the jobs as airline pilot and

hotel housekeepeer were significant at the 5% level.

Given the existing positive attitudes (Table 5) it

would be difficult to expect substantial change. One

interesting result was that the most important shifts

occurred in pupils who either had the careers

presentation by the tourism specialist or were simply

asked to study the booklet on their own. The

presentation by the teacher within the framework of

the normal careers orientation as currently practised

in Greek schools had little effect. The percentage of

pupils interested in at least one job in tourism

increased from 61% (Table 8) to 68% and the total

number of jobs in which they were interested

increased by 29%. In ot her words although many of

the effects of the exposure to careers information

were not statistically significant t here is sufficient

evidence to draw the view that overall there was a

broadeni ng of the understanding of what constitutes

the tourism sector and that the level of interest

increased.

Table 8 Interest in touri sm jobs

UK Greece

(%) (%)

Definitely interested in one or more jobs in tourism

Possibly interested in one or more jobs in tourism

Not interested in any tourism jobs

Total sample

57 61

31 31

11 9

176 152

Apparently there is a clear and significant trend in both countries

in the Chi-squared test versus the equal frequencies (UK:

X2=32.24, e=0. 00; GR: Z -~=41.33, ct=0.00). The difference

between the countries is not significant (g 2 = 0.281, ~t = 0.85).

Before careers i nformati on

Identification as a tourist job

(%) Interest

After careers i nformati on

Identification as a touri st job

(%) Interest

Chi -squared test

Identification Interest

Airline pilot 38 9 46 18

Officer on cruiseliner 69 13 74 16

Hotel manager 84 22 89 27

Leisure centre manager 43 9 34 8

Tourist police officer 80 11 82 11

Tourist information officer 89 12 96 16

Restaurant chef 21 l 28 3

Coach driver 50 0 43 1

Airline steward/ess 65 13 80 20

Waiter/ess 31 1 30 2

Tourist guide 92 23 93 25

Ski instructor/monitor 37 8 37 12

Airline check-in staff 15 3 27 5

Hotel receptionist 72 11 82 14

Hotel housekeeper 47 0 45 5

Restaurant owner 28 4 28 7

Travel agent 77 14 84 11

Number 151 151 148 148

Chi-squared test: * = significant at 10% level; ** = significant at 5% level.

156

Concl usi on

Although the main purpose of the study on which

this article is based was to identify and test ways of

familiarizing young people in Greece with working

in tourism, the findings relating to the situation and

attitudes of young people in Greece and the UK are

in many ways more interesting, possibly have a wider

applicability, certainly provide a fertile basis for

speculation and above all suggest the usefulness of

furt her research.

By way of conclusion these findings are grouped

into four inter-related themes each one of which

provides a possible starting point for speculation

and/or for furt her study.

The first is the extent to which the careers support

and the education for tourism is so much bet t er

developed in the UK than in Greece. Against this

background it is suggested that the system works

well in providing young people in the UK with a

relatively broad and realistic view of career options.

In Greece there seems to be a serious problem with

the support which contributes to a situation in

which, by comparison, Greek pupils seem to be at

an earlier, almost ' fantasy' , stage in their thinking

about careers.

Rel at ed to this is the finding that the UK pupils

are more hostile than their Greek counterparts in

their attitudes toward tourism as a career option. It

is interesting to speculate that the ' fantasy' stage of

Greek pupils leads them to have a glamorous and

unrealistic view of tourism careers. But also differ-

ences in their level of experience as tourists and

differences in the empl oyment structures of the two

countries will play an important part in forming

these attitudes. It would be interesting to examine

furt her the extent to which UK pupils' negative view

of tourism jobs is influenced by their personal

experiences as tourists.

There are also important differences between

views about empl oyment in the tourism sector as a

whole and views about individual tourism jobs. The

important message here is that when asked about

particular jobs, the attitudes of the UK pupils

become more positive while those of their Greek

counterparts become less positive than when asked

about tourism empl oyment in general. It can be

argued that it is more realistic to ask about indivi-

dual jobs and that these responses may be more

accurate than those related to tourism as a whole.

This seems to be particularly true in the light of

the final group of findings relating to the different

perceptions as to what constitutes the tourism

sector. There are some interesting omissions and

contrasts in the pupils' perceptions of what consti-

tutes a tourism job. In particular the low level of

identification in both countries of many jobs in the

accommodat i on and catering sector as being part of

tourism, is in many ways surprising and certainly

contains important messages for the provision of

Attitudes to careers in tourism: D Airey and A Frontistis

careers information about tourism. There is clearly

an important task to get the right semantics about

tourism.

Perhaps the most important conclusion of this

study is that t here are so many questions which still

need to be answered about the attitudes of young

people to tourism careers. At a time when tourism is

held out as one of the world' s major industries and

sources of employment' " it would be timely to know

more about what potential recruits think about it, in

order to provide a basis for attracting the best

possible work force.

Acknowledgements

This article draws upon a study supported by tile

Commission of the European Communities (CEC)

and undert aken jointly by Effective Management

International of Athens, Greece and The

Nottingham Trent University UK. The authors

thank the following for their assistance in carrying

out the research and preparing the article: Dr P

Lytras, Professor of Tourism, Technical Institute of

Athens, Dr J Haliklas, Athens University of

Economics, Mr V Mortensen, EMI, Athens, Ms S

Goddard, Consultant, Nottingham Business School

and Ms Jennifer Gee, European Business Centre.

References

1. I UOTO Study on the economic impact of tourism on

national economies and international trade, Travel Research

Journal Special Issue. International Uni on of Official Travel

Organizations, Geneva, 1966.

2. Medlik, S., Higher Education and Research in Tourism in

Western Europe. University of Surrey, London, 1966.

3. Mathieson, A. and Wall G., Tourism Economic, Physical and

Social Impacts. Longman, London, 1982.

4. Ross, G. F., What do Australian school leavers want of the

industry? Tourism Management, 1994, 15(1), 62-66.

5. Ross, G. F., Tourism management as a career path:

vocational perceptions of Australian school leavers. Tourism

Management, 1992, 13, 242-247.

6. Ross, G. F., School leavers and their perceptions of employ-

ment in the tourism/hospitality industry. Journal of Tourism

Research, 1992, 2, 28-35.

7. Ross, G. F., Tourism and hospitality industry j ob- - at t ai nment

beliefs and work values among Australian school leavers.

International Journal of Hospitalio' Management, 1992, 11 (4),

319- 33(I.

8. Ross, G. F., Correlates of work responses in the tourism

industry. P, sychological Reports, 1991, 68, 1079-1089.

9. Murphy, P. E., Tourism: A Community Approach. Methuen,

New York, 1985.

10. Choy, D. J. L., The quality of tourism employment. Tourism

Management. 1995, 16(2), 129-139.

11. Purcell, K. and Quinn, J., Exploring the educat i on--empl oy-

ment equation in hospitality management: a comparison of

graduates and HND' s. International Journal ()f Hospitality

Management, 1996, 15( 1 ), 51-68.

12. Baum, T., National Tourism Policies: supplementing the

human resource dimension. Tourism Management, 1994,

15(4), 259-266.

157

Attitudes to careers in tourism: D Air~v and A Frontistis

13. Koko, J. and Guerrier, Y., Overeducation, underempl oyment

and job satisfaction: a study of Finnish hotel receptionists.

htternational Journal ~)f Hospitality Management, 1994, 13(4),

375-386.

14. Caterer and Hotel Keeper, Careers Guide 1995. Caterer and

Hotel Keeper, Sutton, 1995.

15. Gctz, D., Students" work experiences, perceptions and

attitudes towards careers in hospitality and tourism, a longitu-

dinal case study in Spey Valley, Scotland. htternational

Journal of Hospitali~ Management, 1994, 13( 1 ), 25-38.

16. World Travel and Tourism Council, Travel attd Tourism, A

New Economic Perspective. WqTC, Brussels, 1993.

158

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Title:: Management Strategy and Decision MakingDokument4 SeitenTitle:: Management Strategy and Decision MakingShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- EssaywritingDokument5 SeitenEssaywritingapi-314279477Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Nature of Strategic ManagementDokument43 SeitenThe Nature of Strategic ManagementShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Title:: Anagement Concept: Case Study 2Dokument7 SeitenTitle:: Anagement Concept: Case Study 2Shoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 700 WordsDokument5 Seiten700 WordsShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neocon PaymentDokument5 SeitenNeocon PaymentShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dessler hrm12 Tif06Dokument45 SeitenDessler hrm12 Tif06Razan Abuayyash100% (1)

- Diploma in Hospitality Management ProspectusDokument8 SeitenDiploma in Hospitality Management ProspectusShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brazil Plastics 2013Dokument31 SeitenBrazil Plastics 2013THANGVUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Warehouse Planning ENUDokument12 SeitenWarehouse Planning ENUVaibhav BindrooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diploma in Hospitality Management ProspectusDokument8 SeitenDiploma in Hospitality Management ProspectusShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Selection Interview AssignmentDokument3 SeitenSelection Interview AssignmentShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art:10.1007/s10490 007 9060 5Dokument19 SeitenArt:10.1007/s10490 007 9060 5Shoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Highstone Electronics Case StudyDokument2 SeitenHighstone Electronics Case StudyShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quality and System ManagementDokument16 SeitenQuality and System ManagementurvpNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 I-Chao LeeDokument19 Seiten11 I-Chao LeeShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wor6562 GDT Q3 2011Dokument36 SeitenWor6562 GDT Q3 2011Shoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines Volunteer Work: Number 7Dokument2 SeitenGuidelines Volunteer Work: Number 7Shoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- References: Unpublished Bachelor Thesis, Mikkeli University of Applied Sciences, Finland, 81Dokument1 SeiteReferences: Unpublished Bachelor Thesis, Mikkeli University of Applied Sciences, Finland, 81Shoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- EssaywritingDokument5 SeitenEssaywritingapi-314279477Noch keine Bewertungen

- Capital BudgetingDokument78 SeitenCapital BudgetingAnkit Jain100% (1)

- Efficiency Vs EffectivenessDokument9 SeitenEfficiency Vs EffectivenessjibharatNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Test of The Impact of Leadership Styles On Employee Performance: A Study of Department of Petroleum ResourcesDokument12 SeitenA Test of The Impact of Leadership Styles On Employee Performance: A Study of Department of Petroleum ResourcesShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rpi 0605Dokument13 SeitenRpi 0605Shoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Your Bibliography - 28 Sep 2014Dokument1 SeiteYour Bibliography - 28 Sep 2014Shoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Your BibliographyDokument2 SeitenYour BibliographyShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brien T Web PG PlatoDokument3 SeitenBrien T Web PG PlatoShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment Brief USN Jan14Dokument8 SeitenAssignment Brief USN Jan14Shoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 1 Case DanoneDokument19 SeitenAssignment 1 Case DanoneShoaib ZaheerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital BudgetingDokument78 SeitenCapital BudgetingAnkit Jain100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Sas1 Gen 002Dokument21 SeitenSas1 Gen 002Luna ValeriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maatua Whangai - A HistoryDokument24 SeitenMaatua Whangai - A HistoryKim Murphy-Stewart100% (3)

- W L IB CAS Handbook 2024.docx 1Dokument19 SeitenW L IB CAS Handbook 2024.docx 1Cyber SecurityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art AppreciationDokument4 SeitenArt AppreciationJhan Carlo M BananNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key 24Dokument4 SeitenKey 24stillaphenomenonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding SelfDokument17 SeitenUnderstanding SelfSriram GopalanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q3 5 Thesis Statement OutliningDokument48 SeitenQ3 5 Thesis Statement OutlininghaydeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Competences For Medical EducatorsDokument10 SeitenCompetences For Medical EducatorsTANIAMSMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan ClothesDokument8 SeitenLesson Plan ClothesMonik IonelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specific Learning DisabilitiesDokument22 SeitenSpecific Learning Disabilitiesapi-313062611Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Plan For DiarrheaDokument3 SeitenTeaching Plan For DiarrheaRoselle Angela Valdoz Mamuyac88% (8)

- (Language, Discourse, Society) Ian Hunter, David Saunders, Dugald Williamson (Auth.) - On Pornography - Literature, Sexuality and Obscenity Law-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1993) PDFDokument302 Seiten(Language, Discourse, Society) Ian Hunter, David Saunders, Dugald Williamson (Auth.) - On Pornography - Literature, Sexuality and Obscenity Law-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1993) PDFnaciye tasdelenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flanders Fields Shared Reading LessonDokument2 SeitenFlanders Fields Shared Reading Lessonapi-289261661Noch keine Bewertungen

- Is There A Scientific Formula For HotnessDokument9 SeitenIs There A Scientific Formula For HotnessAmrita AnanthakrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MPA LeadershipDokument3 SeitenMPA Leadershipbhem silverioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Art at PVO Lesson Plan: ND RD TH THDokument3 SeitenEnvironmental Art at PVO Lesson Plan: ND RD TH THapi-404681594Noch keine Bewertungen

- HRP Final PPT Seimens Case StudyDokument17 SeitenHRP Final PPT Seimens Case StudyAmrita MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Methods and Techniques: The K-12 ApproachDokument45 SeitenMethods and Techniques: The K-12 Approachlaren100% (1)

- Embedded QuestionsDokument20 SeitenEmbedded QuestionsNghé XùNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iseki Full Set Parts Catalogue DVDDokument22 SeitenIseki Full Set Parts Catalogue DVDjayflores240996web100% (134)

- WHS Intro To Philosophy 2008 Dan TurtonDokument111 SeitenWHS Intro To Philosophy 2008 Dan TurtonDn AngelNoch keine Bewertungen

- MCR Syl 17-18 ScottDokument2 SeitenMCR Syl 17-18 Scottapi-293143852Noch keine Bewertungen

- Definition of Violent BehaviorDokument3 SeitenDefinition of Violent BehaviorChristavani EfendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource Management 15Th Edition Dessler Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDokument35 SeitenHuman Resource Management 15Th Edition Dessler Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFEricHowardftzs100% (7)

- Institutional PlanningDokument4 SeitenInstitutional PlanningSwami GurunandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategies For Shopping Mall Loyalty: Thesis SummaryDokument26 SeitenStrategies For Shopping Mall Loyalty: Thesis SummaryVictor BowmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLP-COT Q1 Eng7 Module 1Dokument4 SeitenDLP-COT Q1 Eng7 Module 1Ranjie LubgubanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15PD211 - Aptitude II (Foundation) - Teacher'sDokument45 Seiten15PD211 - Aptitude II (Foundation) - Teacher'sShubham Kumar Singh0% (2)

- Great Barrier Reef Educator GuideDokument24 SeitenGreat Barrier Reef Educator GuideLendry NormanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Power Dynamics in NegotiationDokument52 SeitenPower Dynamics in Negotiationrafael101984Noch keine Bewertungen