Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ethics Watch Summary Judgment Brief

Hochgeladen von

Colorado Ethics WatchCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ethics Watch Summary Judgment Brief

Hochgeladen von

Colorado Ethics WatchCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

DISTRICT COURT, CITY AND COUNTY OF

DENVER, COLORADO

Court Address: 1437 Bannock Street

Denver, Colorado 80202

Plaintiff: COLORADO REPUBLICAN PARTY

v.

Defendants: SCOTT GESSLER, in his capacity as

Colorado Secretary of State

and

Intervenor Defendant: COLORADO ETHICS

WATCH

Attorneys for Intervenor Defendant Colorado

Ethics Watch:

Luis Toro, #22093

Margaret Perl, #43106

Colorado Ethics Watch

1630 Welton Street, Suite 415

Denver, Colorado 80202

Telephone: (303) 626-2100

Fax: (303) 626-2101

E-mail: ltoro@coloradoforethics.org

pperl@coloradoforethics.org

COURT USE ONLY

Case Number:2014CV031851

Division/Courtroom: 409

BRIEF OF INTERVENOR DEFENDANT IN RESPONSE TO

PLAINTIFFS MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Intervenor Defendant Colorado Ethics Watch (Ethics Watch) by their undersigned

attorneys, respectfully submits this brief in response to Plaintiff Colorado Republican Party

(CRP)s Motion for Summary Judgment.

I. INTRODUCTION

Major political parties enjoy a privileged position in Colorado election law because

candidates can access the ballot through the political party structure with great ease compared to

unaffiliated candidates. In order to protect against the corrupting influence of political money, a

2

state may restrict contributions to political parties, upon which a candidates access to the ballot

depends including by limiting the amount any one person may contribute to a political party

and by prohibiting direct corporate or labor union contributions to political parties. A long line of

cases affirms that these political party contribution limits and source restrictions do not violate

the First Amendment.

Though cast in terms of the right to make independent expenditures, the CRPs complaint

in substance asks the Court to permit it to use the device of an independent expenditure

committee (IEC or Super-PAC

1

) to nullify the political party contribution limits established

in the Colorado Constitution. Because Colorados Super-PAC statute, C.R.S. 1-45-107.5, does

not purport to override contribution limits or the corporate/labor union contribution ban for

political parties, and because CRP is not otherwise entitled to evade the contribution limits and

source prohibitions established in the Colorado Constitution, the Court should summarily enter a

declaratory judgment that contributions to the CRP Super-PAC must count against the

contribution limits applicable to the CRP and must comply with the Colorado Constitutions

source prohibitions applicable to political parties.

II. RESPONSE TO CRPS STATEMENT OF UNDISPUTED FACTS

1.-7. Undisputed.

8. Ethics Watch stipulates to all but the final sentence of Paragraph 8.

1

The term Super-PAC was invented by a political reporter to distinguish independent

expenditure-only political action committees, post-Citizens United entities that may raise

unlimited money but may not coordinate with or contribute to candidates, from traditional

political action committees that may contribute directly to candidates but are subject to

contribution limits. Dave Levinthal, How Super PACs Got Their Name, Politico, January 10,

2012, posted at http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0112/71285.html (accessed August 19,

2014). In Colorado law, traditional PACs are called political committees, see Colo. Const. art.

XXVIII, 2(12) and Super-PACs are called independent expenditure committees, see C.R.S.

1-45-103(11.5).

3

9.-11. Undisputed.

12. Ethics Watch stipulates that Exhibit B is a true copy of the Standing Rules that

govern the CRPs Super-PAC.

III. ADDITIONAL MATERIAL UNDISPUTED FACTS

1. On or about August 20, 2012, CRP formed and registered a Super-PAC under the

name of the Colorado Republican Party Independent Expenditure Committee (Former Super-

PAC). The Former Super-PAC reported $85,847.65 in contributions and the same amount of

expenditures to the Secretary of State. CRP raised funds for the Former Super-PAC in

compliance with the contribution limits and source provisions under the campaign finance limits

applicable to a state political party committee. CRP filed the Former Super-PACs final

campaign finance report and terminated the Former Super-PAC on or about February 7, 2014.

Complaint at 13; Intervenors Answer at 13.

2. Since the current CRP Super-PAC was registered in May 2014, it has received

several contributions from individuals in excess of the contribution limits for political parties

established in Article XXVIII and at least one contribution from a corporation as reported on

filings with the Secretary of States office, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit 1. CRP Brief

at 10.

IV. THE SUMMARY JUDGMENT STANDARD IN A DECLARATORY ACTION

As a general rule, summary judgment is warranted only when the moving party

demonstrates both the absence of disputed issues of material fact and that it is entitled to

judgment as a matter of law. C.R.C.P. 56(c). In a declaratory judgment action, however, a

summary judgment may be entered against the moving party, or providing relief different than

that asked for by the moving party, so long as there are no disputed issues of material fact. See

4

C.R.C.P. 54(d) (Except as to a party against whom a judgment is entered by default, every final

judgment shall grant the relief to which the party in whose favor it is rendered is entitled, even if

the party has not demanded such relief in his pleadings); Saxe v. Bd. of Trustees of Metro. State

College of Denver, 179 P.3d 67, 73 (Colo. App. 2007) (declaratory judgment may be either

affirmative or negative in form and effect. The better practice is to enter a declaratory judgment

even if it is adverse to the plaintiff seeking such judgment) (citations omitted). Thus, in the

absence of material factual disputes, the Court may enter summary judgment declaring that

CRPs SuperPAC is subject to political party contribution limits, without the formality of a

cross-motion for summary judgment or an additional reply brief from Ethics Watch. See also

C.R.C.P. 1.

V. ARGUMENT

After a series of U.S. Supreme Court cases removing restrictions on outside actors

participating in political campaigns at the federal and state level, CRP feels constrained by the

constitutional and statutory limits on political party contributions which have withstood similar

court challenges. Instead of seeking a legislative solution to change the constitution and statute in

order to adopt the same rules of the game as other 527s and independent expenditure

committees (CRP Brief at 20), CRP presents this court with a selective reading of federal

campaign finance cases in support of a claimed First Amendment right to unlimited contributions

that would trump decades of settled law. CRP must comply with Colorado law which does not

limit the amount of expenditures made by the CRP Super-PAC but requires its spending be

made with money raised subject to the political party contribution limits and prohibitions. Such

contribution limits and prohibitions have been repeatedly upheld in the face of constitutional

challenges.

5

A. The Undisputed Facts Show That the Super-PAC is Controlled By The CRP.

CRP explicitly seeks a declaratory order that that it may sponsor, maintain, and operate

the Super-PAC in question. (CRP Brief at 21). Regardless of whether the Court agrees with CRP

that the definition of political party in Article XXVIII of the Colorado Constitution might not

reach a truly independent Super-PAC, the undisputed facts show that this committee is a

component of CRP and its activities are legally considered coordinated with CRP. Therefore,

all contribution limitations and source prohibitions applicable to political parties are binding

upon the CRP Super-PAC.

Under Colorado campaign finance law expenditures or spending are coordinated with a

political party if a person makes those expenditures under the control of thatpolitical party.

Rules Concerning Campaign and Political Finance Rule 1.4, 8 C.C.R. 1505-6 (2012).

Expenditures that are coordinated with a political party are considered a contribution to the

political party, subject to all limits and prohibitions on party contributions. See Colo. Const. art.

XXVIII 5(3); see also Republican Party of N.M. v. King, 741 F.3d 1089, 1103 (10th Cir. 2013)

(if a group was indirectly controlled by a political party and considered coordinated then

contributions would be subject to political party limits). The undisputed facts in this case show

that the CRP Super-PAC is under the control of the political party and part of its state-party

apparatus.

According to the undisputed facts, the CRP Super-PAC is organized as a standing

committee and separate segregated fund of CRP under the appointment authority of State

Chairman Ryan Call. Chairman Call appoints the Executive Director and management

committee members, names replacements when a members term expires, and can remove

members certain to subject provisions. Chairman Call and other agents and representatives of

6

CRP will be soliciting contributions to the CRP Super-PAC. The CRP Super-PAC must abide by

the CRP Bylaws, including the pre-primary neutrality provisions, and any rules adopted by the

CRP Super-PAC that are in conflict the CRP Bylaws or any rule of the Republican National

Committee are deemed inoperative. The filings for the CRP Super-PAC list the Colorado

Republican Central Committee as its parent corporation.

The CRP explains that the rules of the CRP Super-PAC are designed to avoid

coordination of expenditures with any candidates, thus ensuring that the IECs expenditures are

truly independent. (CRP Brief at 2). While the rules might succeed in keeping the CRP Super-

PAC independent from candidates, they do not render it independent from the party the crucial

question when determining if political party contribution limits and prohibitions apply.

Our campaign finance system requires disclosure by independent political actors, outside

of any political party, that raise and spend money to influence Colorado state elections. (CRP

Brief at 18-19). These groups may have a partisan bent, but they are not directed by the political

parties. CRP admits that it has created this Super-PAC so that the facts, argument, and

perspective of the Colorado Republican Party can be expressed. (CRP Brief at 20). Chairman

Call and CRP are free to support and fundraise for any number of independent expenditure

committees that are sympathetic and compatible with the CRP view and Republican candidates.

But that is not enough to satisfy them. The only reason this CRP Super-PAC was created is so

that CRP may control it. That strategy is legal under Colorado campaign finance law, but only so

long as the connected Super-PAC under control of the CRP complies with all contribution limits

and prohibitions in the Colorado Constitution. This is exactly how the CRPs Former Super-

PAC operated.

7

B. Colorados Campaign Finance Constitutional Provisions Restrict the

Amount and Source of Contributions that may be received by any Political Party

including CRP.

In 2002, Colorado voters passed Amendment 27, which became Article XXVIII of the

Colorado Constitution. Article XXVIII creates a comprehensive campaign and political finance

system, including disclosure requirements, contribution limits and source restrictions for

candidates, political parties, political committees, issue committees, and small donor committees.

See Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 2. Section 3 imposes both contribution limits and source

prohibitions on political parties which differ from the limits placed on other types of political

actors. A political party may receive no more than $3,400 per calendar year from any person,

candidate or political committee, and not more than $17,075 from a small donor committees (as

defined in Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 2(14).

2

These contribution limits are higher than the limits

on political committees, small donor committees, and candidates. Political parties (and

candidates) are absolutely prohibited from accepting contributions from corporations and labor

unions. See Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 3(4)(a).

3

Because the CRP Super-PAC is controlled by, and coordinated with, the CRP, that

account is subject to these political party contribution limitations and source prohibitions in

Article XXVIII. It is nonsensical for the CRP to argue that political parties are permitted to

operate funds not governed by Section 3s constitutional limits and prohibitions based on the

2

These contribution limits have been increased from the 2002 levels established in 3(3) to keep

pace with inflation. See Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 3(13); Campaign and Political Finance Rule

10.14, 8 C.C.R. 1505-6 (2012).

3

For disclosure purposes, a political party shall be treated as separate entities at the state,

county, local and district levels. Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 7. For all other purposes, political

parties and their statewide, county and election district affiliated organizations are considered to

be a single entity. Id. 2(13).

8

lack of reference to independent expenditure committees anywhere in Article XXVIII. (CRP

Brief at 12-13, 16). There was no deliberate exclusion of Super-PACs from the contribution

limitations and corporate/labor contribution prohibition in Section 3 when Article XXVIII was

enacted, because such committees didnt exist until after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down

the corporate expenditure limitation in Citizens United v. Federal Election Comn, 558 U.S. 310

(2010). Instead, Colorado citizens intended the independent expenditure activities of a political

party to be governed by the express constitutional limitations and prohibitions on political party

contributions as sanctioned by First Amendment jurisprudence in 2002 when Article XXVIII

was adopted.

When interpreting constitutional amendments, the court must look to the existing law at

the time the citizen initiative was adopted to determine the scope and intent of its provisions.

Colorado Ethics Watch v. Senate Majority Fund, 2012 CO 12, 20. Therefore, these provisions

must be interpreted in light of the then-existing law on independent expenditures by political

parties. Two U.S. Supreme Court cases defined the contours of existing law when voters adopted

Article XXVIII in 2002: Colorado Republican Fed. Campaign Comm. v. Federal Election

Commn, 518 U.S. 604, 617-18 (1996) (Colorado Republicans I), which is relied upon by CRP

in this case, and Federal Election Commn v. Colorado Republicans Fed. Campaign Comm, 533

U.S. 431, 440 (2001) (Colorado Republicans II), a case not cited by CRP to this court but

equally as important to this matter.

In Colorado Republicans I, the party successfully challenged a federal campaign finance

provision which imposed a limit on the amount that a political party could spend related to a U.S.

Senate candidate election (at the time of the case the cap in Colorado was $103,000). See

Colorado Republicans I, 518 U.S. at 611. The U.S. Supreme Court held that the First

9

Amendment prohibited any caps placed on expenditures made by a political party that were

independent from candidate campaigns. Id. at 616. When the case returned to the high court five

years later, it rejected the First Amendment challenge to limits on political party contributions to

candidates in the form of coordinated expenditures. Colorado Republicans II, 533 U.S. at 446-

447. Most of this second opinion describes how political parties are inherently different than

other outside political actors and that this difference justifies the challenged contribution limits.

See id at 481-82 (Indeed, parties capacity to concentrate power to elect is the very capacity that

apparently opens them to exploitation as channels for circumventing contribution and

coordinated spending limits binding on other political players.). Both Colorado Republicans I

and II acknowledged and did not question that all monies taken in by political parties were

subject to federal law contribution limits of $20,000 per donor (with no corporate or union

contributions allowed) even if that money was used for independent expenditures. See Colorado

Republicans I, 518 U.S. at 617; Colorado Republicans II, 533 U.S. at 458.

This was the law when the amendment was adopted, and the court must interpret the

voters intent as consistent with this precedent regarding political parties making independent

expenditures as opposed to CRPs attempt to read permission for its desired activities where

none is given. The only reasonable interpretation of the provisions in Article XXVIII is that the

citizens intended to institute the constitutionally-approved system for political parties making

independent expenditures under Colorado Republicans I and II: a separate bank account within

the party subject to contribution limits and source prohibitions where independent expenditures

are disclosed but are not subject to any caps or spending limits. That was the law in 2002, and

neither the subsequent creation of Super-PACs in statute nor recent case law regarding

expenditures by outside groups has changed that.

10

C. C.R.S. 1-45-107.5 Does Not Override Contribution Limits and Source Prohibitions

Applicable To Political Parties.

Prior to the Citizens United ruling in January 2010, Colorado law had no need for a

Super-PAC statutory provision because corporations and unions were prohibited from making

expenditures except through a connected political committee (subject to its own contribution

limits). Colo. Const. art. XXVIII 3(4)(a). See Citizens United, 558 U.S. at 370 (A campaign

finance system that pairs corporate independent expenditures with effective disclosure has not

existed before today); In Re Interrogatories Propounded by Governor Ritter, Jr. Concerning the

Effect of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commn, 558 U.S.___ (2010) on Certain Provisions

of Article XXVIII of The Constitution of the State of Colorado, 227 P.3d 892 (Colo. 2010). After

that ruling, the Colorado General Assembly chose to create by statute Super-PACs to ensure

consistent public disclosure of these spending by new groups in C.R.S. 1-45-107.5, effective

May 25, 2010. However, when Super-PACs were created in statute, deliberate choices were

made and reflected in the statutory language.

CRPs Complaint makes much of the fact that the Super-PAC statute, C.R.S. 1-45-

107.5, does not expressly prohibit parties from forming Super-PACs. A closer examination of the

statute reveals that the General Assembly intended for political party contribution limits to

continue to apply to any party-sponsored Super-PACs just as limits had always applied to the

independent expenditures made by parties under Colorado Republicans I and II.

First, with regard to the application of Article XXVIII contribution limits to political

party-controlled Super-PACS, the Super-PAC statute simply states that Super-PACs are not

subject to the constitutional limitations in Article XXVIII, 3(5) the contribution limits for

political committees. See CRS 1-45-103.7(2.5). This statute does not say Super-PACs are free

11

from all contribution limits in Article XXVIII. As seen above, the political party contribution

limit is contained in 3(3) a provision not mentioned in the statutory exclusion. The General

Assembly deliberately chose not to exclude that contribution limitation (which has never been

declared unconstitutional), and therefore, Super-PACs created by parties under the statute are

still subject to the 3(3) contribution limits.

The statute also does not exempt political party-controlled Super-PACs from the Article

XXVIII 3(4) prohibition on receipt of corporate or labor union contributions. C.R.S. 1-45-

103.7(1) states that nothing prohibits corporations and labor organizations from contributing to

political committees. As CRP correctly notes, political parties are excluded from the definition of

political committee in Article XXVIII, 2(12)(b). (CRP brief at 16). This statute is not a

removal of the constitutional prohibition on corporate and labor union contributions to political

parties. See also In Re Interrogatories, 227 P.3d at 892 (striking down Article XXVIII bans on

corporate and labor spending on expenditures and electioneering communications but not

prohibition on direct contributions to candidates and political parties). Reading these statutory

provisions together (against the background of constitutional provisions and Supreme Court

precedent), even though a political party may be a person pursuant to C.R.S. 1-45-107.5(3)

that can set up a Super-PAC, its Super-PAC is still subject to constitutional contribution

limitations and prohibitions for political parties.

In summary, Colorados constitutional and statutory provisions allow a political party to

set up a separate bank account that is a Super-PAC to makes expenditures without coordinating

with Colorado candidates, but all contributions to that Super-PAC (whether direct or funneled

through CRP) must comply with the contribution limitations and source prohibitions applicable

12

to political parties.

4

This is true at the federal level as well where independent expenditures

must be paid for with federally permissible funds by federal political parties and Citizens

United has not changed that requirement. See FEC Campaign Guide for Political Party

Committee at 62 (August 2013), attached as Exhibit 2.

D. No First Amendment Rights of CRP are Violated by Colorados Constitutional and

Statutory Regulation of Contributions to Political Parties.

Because CRPs plans for its Super-PAC run afoul of Colorados Constitution and

statutes, the only way that CRP can sponsor a Super-PAC in the unrestricted manner that it seeks

is to convince the court that CRP has an overriding First Amendment Right to do so. It does not.

Since the post-Watergate campaign finance regulations for federal elections were adopted

by Congress, campaign finance case law has drawn a distinction between expenditures and

contributions. As a general rule, the First Amendment does not permit caps on expenditures

(political spending) and such limits are subject to the highest standard of review: strict scrutiny.

See Colorado Republicans I, 518 U.S. at 610; Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 44-45 (1976).

Contributions, on the other hand, may be regulated both as to amount (through caps on

contributions) and as to source (e.g., prohibitions on contributions from corporations, labor

unions and foreign citizens). See Buckley, 424 U.S. at 20-21; Dallman v. Ritter, 225 P.2d 610,

621-22 (Colo. 2010). Because contribution limits are not a direct restraint on individual speech

but merely limit the ability to give money to approve of a candidate, party or political

organizations message, such limits are subject to the lower standard of exacting scrutiny in First

4

Nor is this a unique structure not applied elsewhere in Colorado campaign finance law. For

example, federal political committees who seek to support or oppose state candidates may only

do so using funds that comply with Colorado contribution limits. See Rules Concerning

Campaign and Political Finance Rule 7.1.1(c), 8 C.C.R. 1505-6 (2012).

13

Amendment law. See Citizens United, 558 U.S. 310, 356-57 (2010); Colorado Republicans I,

518 U.S. at 614-15; Buckley, 424 U.S. at 21.

1. CRPs Right to Make Independent Expenditures in Unlimited Amounts without

Coordination with Candidates is Not Affected by this Case.

Nothing in Article XXVIII or the Super-PAC statute sets limits on the amount of

independent expenditures made through CRPs sponsored fund so long as it follows the

guidelines in Colorado Republicans I and II to avoid coordination with the state candidates

affected by that spending. To the extent that recent case law has re-affirmed CRPs right to make

unlimited independent expenditures, that does not answer the question presented by CRP.

CRP attempts to use case law interpreting restrictions on expenditures to support its

argument that it must be relieved from restrictions contributions to its Super-PAC. Citizens

United and Colorado Republicans I analyzed restrictions on expenditures and did not affect

longstanding U.S. Supreme Court rulings upholding contribution limitations to political parties

(referred to as soft money in federal law). See Citizens United, 558 U.S. at 361 (This case,

however, is about independent expenditures, not soft money); Dallman, 225 P.2d at 622 (The

Supreme Court decision in Citizens United addressed only expenditure limits and disclosure

requirements; thus, it does not control our analysis of Amendment 54s contribution limits.).

The mere fact that raising contributions in higher amounts and from more sources could allow

the CRP Super-PAC to spend more on its independent expenditures does not mean that these

contribution regulations are treated as expenditure limits for constitutional analysis. The question

of whether or not CRP has a constitutional right to disregard the contribution limits and

prohibitions to political parties in Article XXVIII must be analyzed using precedent examining

contribution limits instead of the expenditure limit cases cited by CRP.

14

2. The U.S. Supreme Court has Consistently Upheld Contribution Limitations and

Prohibitions as Applied to Political Parties as Constitutional.

As stated in Colorado Republicans I, reasonable contribution limits directly and

materially advance the Government's interest in preventing exchanges of large financial

contributions for political favors. 518 U.S. at 615 (citing Buckley, 424 U.S. at 26-27).

Contribution limits permit[] the symbolic expression of support evidenced by a contribution

but do[] not in any way infringe the contributors freedom to discuss candidates and issues.

McCutcheon v. Federal Election Comn, 134 S. Ct. 1434, 1444 (2014) (quoting Buckley, 424

U.S. at 21, notations in original). Under the lower level of scrutiny applied by the Supreme

Court, contribution limits are valid so long as they are closely drawn to match a sufficiently

important government interest. McConnell v. Federal Election Comn, 540 U.S. 93, 136 (2003).

This lower scrutiny gives deference to the legislatures ability to weigh competing interests and

provides legislation sufficient room to anticipate and respond to concerns about circumvention

of regulations designed to protect the integrity of the political process. Id. at 137.

CRP admits that Article XXVIIIs contribution limits and prohibitions continue to apply

to political parties when it states that such constitutional provisions have not yet been

successfully challenged in court. (CRP Brief at 16). In Colorado Republicans II, there was no

question or challenge to the fact that the political party must continue to comply with the

$20,000 per year limit on contributions from individuals even if that money was used for

independent expenditures. See id. at 458-61. Subsequently, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld

additional contribution limitations on political parties which banned receipt of soft money

contributions outside the statutory limitations as constitutional means to address the

governments interest in preventing corruption and appearance of corruption:

15

Given this close connection and alignment of interests, large soft-

money contributions to national parties are likely to create actual

or apparent indebtedness on the part of federal officeholders,

regardless of how those funds are ultimately used.

McConnell, 540 U.S. at 155. This Supreme Court analysis of political party contribution

limitations is still governing law today. See Republican Natl Comm. v. Federal Election Comn

(In re Anh Cao), 619 F.3d 410, 422 (5

th

Cir. 2010) (rejecting constitutional challenge to

contribution limits on political parties because we do not read Citizens United as changing how

this court should evaluate contribution limits on political parties and PACs) (Cao). The most

recent U.S. Supreme Court case on contribution limitations (striking down aggregate donor

limits not at issue in this case) also reaffirms that contribution limits as applied to political parties

are constitutional and still binding. See McCutcheon, 134 S. Ct. at 1451 n.6 (Our holding about

the constitutionality of the aggregate limits clearly does not overrule McConnells holding about

soft money.).

Most relevant is the post-Citizens United case of Republican Natl Comm.et al. v. Federal

Election Comn, 698 F. Supp. 2d (D.D.C 2010) (RNC). This case involved a First Amendment

challenge brought by national and state party committees challenging the contribution limits for

political parties very similar to CRPs complaint. The political party sought to raise contributions

not subject to statutory contribution limits for use in certain activities not connected to federal

candidate races and argued that the First Amendment prohibited limiting contributions in those

circumstances. Id. at 155-56. The special three-judge panel (including one D.C. Circuit Judge)

held unanimously that Citizens United did not disturb McConnells holding with respect to the

constitutionality of [statutory] limits on contributions to political parties. Id. at 153. As an initial

matter, the court rejected the argument that contribution limits functioned as a de facto

expenditure limitation and should be subject to higher level of scrutiny. Id. at 156. Then the court

16

found that McConnells holding that there is no First Amendment violation in applying

contribution limitations and prohibitions to all funds raised and spent by political parties

regardless of how that money is spent is still valid and binding after Citizens United. Id. at 157-

58. Upon appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court summarily affirmed this holding in Republican Natl

Comm.et al. v. Federal Election Comn, 130 S.Ct. 3543 (2010).

5

Thus, governing Supreme Court

precedent states that contribution limits and prohibitions can constitutionally be applied to

political parties like CRP regardless of whether they intend to use the money for independent

expenditures. See McCutcheon, 134 S.Ct. at 1451 (Those base limits remain the primary means

of regulating campaign contributions.).

Nor has this line of cases upholding contribution limitations on parties been overruled by

post-Citizens United cases allowing Super-PACs without contribution limits or prohibitions for

other political actors. These cases reaffirm a right for outside groups to operate without

contribution limits for independent expenditures because of their different position in campaigns

than political parties or candidates. See Carey v. Federal Election Comn, 791 F. Supp. 2d 121,

131 (D.D.C. 2011) (non-connected non-profits are not the same as political parties and do not

cause the same concerns); SpeechNow.org, et al. v. Federal Election Comn, 599 F.3d 686, 695

(D.C. Cir. 2010) (distinguishing between independent expenditures made by political parties at

issue in Colorado Republicans I and such expenditures by non-connected groups). Unlike non-

connected Super-PACs established under C.R.S. 1-45-107.5, CRP and all political parties are

inherently linked with candidates and officeholders. This difference has been recognized by the

courts to allow for different First Amendment treatment: more onerous contribution restrictions

5

A U.S. Supreme Court summary affirmance is not merely a denial of certiorari, but action with

precedential value with respect to the precise issues presented and necessarily decided by those

actions. Anderson v. Celebrezze, 460 U.S. 780, 784 n.5 (1983).

17

may be placed on political parties than independent groups. Republican Party of N.M. v. King,

741 F.3d 1089, 1100 (10th Cir. 2013). See also Long Beach Area Chamber of Commerce v. City

of Long Beach, 603 F.3d 684, 696, 698 (9th Cir. 2010) (distinguishing permissible contribution

limits on political parties from impermissible limits on non-connected committees); Cao, 619

F.3d at 422 (noting the precise role that political parties fill that gives rise to the Government's

compelling interest in regulating their coordinated expenditures and contributions); N.C. Right

to Life, Inc. v. Leake, 525 F.3d 274, 292-93 (4th Cir. 2008) (McConnell specifically emphasized

the difference between political parties and independent expenditure political committees, which

explains why contribution limits are acceptable when applied to the former, but unacceptable

when applied to the latter).

Just this month, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia denied a preliminary

injunction in a similar challenge by the national Republican and Libertarian parties seeking to

declare federal contribution limits to political parties unconstitutional as applied to independent

expenditures. See Rufer et al.v. Federal Election Comn, No.14-cv-837, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

114762 (D.D.C. August 19, 2014). The Rufer opinion held that the parties are not likely to

succeed on the merits because their constitutional claims are in tension with forty years of

Supreme Court jurisprudence upholding contribution limits to political parties. Id. at *22. The

fact that national political parties pursuing this parallel federal court case must overturn decades

of Supreme Court precedent to get the same result sought by CRP belies CRPs argument that

current First Amendment jurisprudence guarantees a political partys right to use unrestricted

funds for independent expenditures.

[P]olitical parties have influence and power in the Legislature that vastly exceeds that of

any interest group. McConnell, 540 U.S. at 188. Colorado citizens have spoken and decided that

18

the potential for corruption warrants limitations on contributions to political parties. See Colo.

Const. art. XXVIII 3(3) and 3(4). In Colorado, as in federal law and other states, political

parties are simply differently situated and appropriately treated differently than corporations,

labor organizations, or other associations. See McConnell, 540 U.S. at 144 (The idea that large

contributions to a national party can corrupt or, at the very least, create the appearance of

corruption of federal candidates and officeholder is neither novel nor implausible.); Colorado

Republicans I, 518 U.S. at 617 (noting the potential for corruption linked to the ability of

donors to give sums up to $20,000 to a party which may be used for independent party

expenditures for the benefit of a particular candidate); Republican Party of N.M, 741 F.3d. at

1100 (groups that do not share a party relationship are treated differently); EMILYs List v.

Federal Election Comn, 581 F.3d 1, 14 (D.C. Cir. 2009) (non-profit groups do not have the

same inherent relationship with federal candidates and officeholders that political parties do).

Parties thus perform functions more complex than simply electing candidates; whether they like

it or not, they act as agents for spending on behalf of those who seek to produce obligated

officeholders. Colorado Republicans II, 533 U.S. at 453. When CRP Chairman Call actively

fundraises for the CRP Super-PAC (which will only support Republican party candidates in the

general election without choosing sides in the primary election), clearly candidates will know

these donations will help their campaign. This potential corrupting influence justifies the

contribution limits and corporate and labor union prohibitions. Otherwise, the CRP Super-PAC

could become a way to evade the limits and corporate and labor union prohibitions on

contribution to Colorado candidates. See McConnell, 540 U.S. at 145-46 (recognizing evidence

in record of soft money donations to political parties used to create debt on the part of

19

officeholders in circumvention of contribution limits to candidates); Republican Party of N.M.,

741 F.3d at 1099.

CRP makes a lengthy policy argument that political parties should be able to have the

same playing field in the marketplace of ideas instead of being drowned out by outside

spenders including those groups not subject to disclosure. (CRP Brief at 20). U.S. Supreme

Court precedent makes clear that a desire to level electoral opportunities between the wealthy

and those with less money to spend on elections is not a valid governmental interest under the

First Amendment. Davis v. FEC, 554 U.S. 724, 742 (2008). CRPs argument should be made to

the people of Colorado and the legislature in support of amendments to Article XXVIII to raise

or remove the contribution limits and prohibitions on political parties. Colorados voters, like

Congress, are fully entitled to consider the real-world differences between political parties and

interest groups when crafting a system of campaign finance. McConnell, 540 U.S. at 188.

Moreover, similar policy arguments have been rejected by the courts, both before and

after Citizens United. See RNC, 698 F. Supp. 2d at 160 n.5 (we recognize the RNCs concern

about this disparity, which, it argues, discriminates against the national political parties in

political and legislative debates. But that is an argument for the Supreme Court or Congress);

Cao, 619 F.3d at 422 (the Supreme Court's analysis fully supports the Government's differential

treatment of political parties because of what Colorado II recognized as a political party's

unique susceptibility to corruption); McConnell, 540 U.S. at 187-89 (rejecting political parties

equal protection challenge because laws discriminate against parties in favor of outside special

interest groups). CRPs policy preferences provide no basis for this court to overturn state

constitutional provisions.

20

VI. CONCLUSION

No one challenges the CRP Super-PACs right to spend unlimited amounts in

independent expenditures to support Republican candidates in state elections. Because CRP

cannot challenge the right of outside groups to similarly spend unlimitedly to support other

candidates, it seeks to remove what it sees as an unfair impediment: Article XXVIIIs

contribution limits and prohibitions on political parties. But these contributions limits are

constitutional and must be applied to any Super-PAC sponsored and controlled by a political

party. Continuing to apply duly-enacted Colorado Constitutional provisions to the CRP Super-

PAC does not offend the First Amendment because the overall effect of the Acts contribution

ceilings is merely to require candidates and political committees to raise funds from a greater

number of persons. Buckley, 424 U.S. at 21-22. The court is bound to enter a declaratory order

that the CRP Super-PAC must comply with the contribution limits and prohibitions in Article

XXVIII.

Respectfully submitted this 22nd day of August 2014,

_____[Original Signature On File]______

Luis Toro, #22093

Margaret Perl, #43106

Attorneys for Intervenor-Defendant Colorado Ethics Watch

21

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that on August 22, 2014, I served a true copy of the above and foregoing through

ICCES on the following:

Richard A. Westfall, Esq.

Allan L. Hale, Esq.

Peter J. Krumholz, Esq.

Hale Westfall, LLP

1600 Stout St., Suite 500

Denver, CO 80202

Matthew Grove, Esq.

Sueanna Johnson, Esq.

Colorado State Attorney General

State Services Section

1300 Broadway, 6th Floor

Denver, CO 80203

_____[Original Signature On File]______

Margaret Perl

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Joint Opening Brief Ethics Watch v. GesslerDokument29 SeitenJoint Opening Brief Ethics Watch v. GesslerColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colorado Cause and Colorado Ethics Watch Complaint Against Scott GesslerDokument6 SeitenColorado Cause and Colorado Ethics Watch Complaint Against Scott GesslerNickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976)Dokument219 SeitenBuckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complaint CIW vs. CJPCDokument5 SeitenComplaint CIW vs. CJPCPeter CoulterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tatad Vs Department of Energy November 5, 1997 (Motion For Reconsideration)Dokument8 SeitenTatad Vs Department of Energy November 5, 1997 (Motion For Reconsideration)Mrk AringzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filed: Patrick FisherDokument55 SeitenFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rappler Inc. Vs BautistaDokument38 SeitenRappler Inc. Vs BautistaRICKY ALEGARBESNoch keine Bewertungen

- (CD) Lawyers Against Monopoly and Poverty V Secretary of Budget and ManagementDokument3 Seiten(CD) Lawyers Against Monopoly and Poverty V Secretary of Budget and ManagementRaine100% (2)

- Free Speech LetterDokument10 SeitenFree Speech LetterRob PortNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maquera v. Borra DigestDokument4 SeitenMaquera v. Borra Digestnadinemuch100% (1)

- Reply Brief Hemp FilingDokument12 SeitenReply Brief Hemp FilingChrisNoch keine Bewertungen

- FACTS: For Consideration of The Court Is An Original Action For Certiorari Assailing TheDokument3 SeitenFACTS: For Consideration of The Court Is An Original Action For Certiorari Assailing TheCeledonio ManubagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lamp Vs Secretary Case DigestDokument2 SeitenLamp Vs Secretary Case DigestRR FNoch keine Bewertungen

- STATCONNNNNDokument21 SeitenSTATCONNNNNJoy S FernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report by CRS Re Alleged ACORN Attainder - Kennth R Thomas 091209Dokument15 SeitenReport by CRS Re Alleged ACORN Attainder - Kennth R Thomas 091209Christopher Earl StrunkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colorado Right To Life Committee, Inc. v. Coffman, 498 F.3d 1137, 10th Cir. (2007)Dokument40 SeitenColorado Right To Life Committee, Inc. v. Coffman, 498 F.3d 1137, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21lamp v. Secretary of DBM GR No.164987Dokument5 Seiten21lamp v. Secretary of DBM GR No.164987Ruab PlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- CU Petition For Rulemaking To FECDokument4 SeitenCU Petition For Rulemaking To FECCitizens UnitedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ready For Ron SuitDokument42 SeitenReady For Ron SuitDaniel UhlfelderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional Law Section 22Dokument13 SeitenConstitutional Law Section 22elainejoy09Noch keine Bewertungen

- Module 8 CasesDokument91 SeitenModule 8 CasesMiller Paulo2 BilagNoch keine Bewertungen

- CONSTI REVIEW Case Digest Compilation (Art. VI) (Partial)Dokument10 SeitenCONSTI REVIEW Case Digest Compilation (Art. VI) (Partial)Francis Ray Arbon FilipinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colorado Republican Federal Campaign Comm. v. Federal Election Comm'n, 518 U.S. 604 (1996)Dokument35 SeitenColorado Republican Federal Campaign Comm. v. Federal Election Comm'n, 518 U.S. 604 (1996)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pamatong vs. COMELECDokument5 SeitenPamatong vs. COMELECJem LicanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines Manila: Corona, J.Dokument71 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Manila: Corona, J.Delsie FalculanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawyers Against Monopoly and Poverty (Lamp) vs. The Secretary of Budget and Management, GR No. 164987 April 24, 2012Dokument7 SeitenLawyers Against Monopoly and Poverty (Lamp) vs. The Secretary of Budget and Management, GR No. 164987 April 24, 2012Ashley Kate PatalinjugNoch keine Bewertungen

- 17CA0883 Campaign Integrity V Colo Pioneer 05-30-2019Dokument28 Seiten17CA0883 Campaign Integrity V Colo Pioneer 05-30-2019Matt ArnoldNoch keine Bewertungen

- StatCon FinalDokument32 SeitenStatCon FinalHannah Keziah Dela CernaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAWYERS AGAINST MONOPOLY AND POVERTY vs. SECRETARY OF DBM - G.R No. 164987Dokument2 SeitenLAWYERS AGAINST MONOPOLY AND POVERTY vs. SECRETARY OF DBM - G.R No. 164987Dan DerickNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAMP Vs Secretary of Budget & ManagementDokument8 SeitenLAMP Vs Secretary of Budget & ManagementMan2x SalomonNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDokument4 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rev. Ely Velez Pamatong vs. Commission on Elections 2004Dokument6 SeitenRev. Ely Velez Pamatong vs. Commission on Elections 2004Lemuel AtupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guingona, Jr. vs. CaragueDokument11 SeitenGuingona, Jr. vs. CaragueBryce KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abakada Guro Party-List v. Purisima - G.R. No. 166715 - April 14, 2008Dokument14 SeitenAbakada Guro Party-List v. Purisima - G.R. No. 166715 - April 14, 2008mjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pamatong Vs COMELECDokument4 SeitenPamatong Vs COMELECmtabcaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- MacHinists v. Street, 367 U.S. 740 (1961)Dokument57 SeitenMacHinists v. Street, 367 U.S. 740 (1961)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States District Court For The District of Puerto RicoDokument14 SeitenUnited States District Court For The District of Puerto RicoJohn E. MuddNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12-19-16 Relply To MTDDokument6 Seiten12-19-16 Relply To MTDPeter CoulterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abakada Vs PurisimaDokument9 SeitenAbakada Vs PurisimaJanet Tal-udanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Randall v. Sorrell, 548 U.S. 230 (2006)Dokument70 SeitenRandall v. Sorrell, 548 U.S. 230 (2006)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dura lex sed lex - Strict interpretation of tax lawsDokument9 SeitenDura lex sed lex - Strict interpretation of tax lawsDanielle Nicole ValerosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fighting The Influence of Big Money in PoliticsDokument4 SeitenFighting The Influence of Big Money in PoliticsSally HayatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Robert Corry Letter To Colorado Attorney General John Suthers Re: Medical Marijuana Legislation HB 1284 and SB 109Dokument7 SeitenRobert Corry Letter To Colorado Attorney General John Suthers Re: Medical Marijuana Legislation HB 1284 and SB 109NickNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAMP v Sec of DBM: Early case on PDAF constitutionalityDokument4 SeitenLAMP v Sec of DBM: Early case on PDAF constitutionalityMil RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- SC Decision on PDAF ConstitutionalityDokument15 SeitenSC Decision on PDAF ConstitutionalitySharonRosanaElaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complaint - DPD Officers Vs Denver & DPPADokument12 SeitenComplaint - DPD Officers Vs Denver & DPPAJacob RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 006 Abakada Guro Party-List v. Purisima, G.R. No. 166715, August 14, 2008, 562 SCRA 251Dokument14 Seiten006 Abakada Guro Party-List v. Purisima, G.R. No. 166715, August 14, 2008, 562 SCRA 251JD SectionDNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7omcb170 PDFDokument6 Seiten7omcb170 PDFCraig O'DonnellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pamatong vs. COMELEC, G.R. No. 161872, April 13, 2004Dokument7 SeitenPamatong vs. COMELEC, G.R. No. 161872, April 13, 2004Anthony John ApuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Belgica VS OchoaDokument15 Seiten1 Belgica VS OchoajafernandNoch keine Bewertungen

- HofR Challenge To ACA DCT 5-12-16Dokument38 SeitenHofR Challenge To ACA DCT 5-12-16John HinderakerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme CourtDokument4 SeitenSupreme CourtSi KayeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pamatong Vs ComelecDokument10 SeitenPamatong Vs Comelecroberto valenzuelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- COMELEC Rules on Presidential Candidate's PetitionDokument5 SeitenCOMELEC Rules on Presidential Candidate's PetitionMctc Nabunturan Mawab-montevistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 161872 April 13, 2004 Rev. Elly Chavez Pamatong, Esquire, Petitioner, COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, RespondentDokument5 SeitenG.R. No. 161872 April 13, 2004 Rev. Elly Chavez Pamatong, Esquire, Petitioner, COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, RespondentcarlgerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Construction Case DigestDokument50 SeitenStatutory Construction Case DigestFrances Rexanne AmbitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harvard Law Review: Volume 130, Number 6 - April 2017Von EverandHarvard Law Review: Volume 130, Number 6 - April 2017Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemVon EverandThe Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harvard Law Review: Volume 130, Number 2 - December 2016Von EverandHarvard Law Review: Volume 130, Number 2 - December 2016Noch keine Bewertungen

- Harvard Law Review: Volume 131, Number 6 - April 2018Von EverandHarvard Law Review: Volume 131, Number 6 - April 2018Noch keine Bewertungen

- Oct 2017 Comment On CPF RulemakingDokument2 SeitenOct 2017 Comment On CPF RulemakingColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 2 of 6Dokument95 Seiten2017 Coleg Per Diem 2 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 1 of 6Dokument122 Seiten2017 Coleg Per Diem 1 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 5 of 6Dokument76 Seiten2017 Coleg Per Diem 5 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electioneering Gap ReportDokument1 SeiteElectioneering Gap ReportColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attorney General Cynthia Coffman Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Dokument13 SeitenAttorney General Cynthia Coffman Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Governor Hickenlooper Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Dokument155 SeitenGovernor Hickenlooper Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 6 of 6Dokument114 Seiten2017 Coleg Per Diem 6 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 3 of 6Dokument93 Seiten2017 Coleg Per Diem 3 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 4 of 6Dokument108 Seiten2017 Coleg Per Diem 4 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- IEC Draft Position Statement On Frivolous DeterminationsDokument2 SeitenIEC Draft Position Statement On Frivolous DeterminationsColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treasurer Stapleton Calendar Nov 1 2016-Jan 31 2017Dokument14 SeitenTreasurer Stapleton Calendar Nov 1 2016-Jan 31 2017Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treasurer Stapleton Calendar Feb-Apr 2017Dokument13 SeitenTreasurer Stapleton Calendar Feb-Apr 2017Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- SoS Wayne Williams Calendar Dec 2016-Feb 2017Dokument14 SeitenSoS Wayne Williams Calendar Dec 2016-Feb 2017Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- LT Governor Donna Lynne Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Dokument95 SeitenLT Governor Donna Lynne Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treasurer Stapleton Calendar 8.1.2016-10.31.2016Dokument14 SeitenTreasurer Stapleton Calendar 8.1.2016-10.31.2016Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- SoS Wayne Williams Jun-Aug 2016 CalendarDokument92 SeitenSoS Wayne Williams Jun-Aug 2016 CalendarColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hickenlooper Calendar Oct-Dec 2016Dokument155 SeitenHickenlooper Calendar Oct-Dec 2016Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hickenlooper Calendar Jul-Sep 2016Dokument132 SeitenHickenlooper Calendar Jul-Sep 2016Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hickenlooper Calendar Apr-Jun 2016Dokument1 SeiteHickenlooper Calendar Apr-Jun 2016Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics Watch Comment On July 26 CPF RulemakingDokument8 SeitenEthics Watch Comment On July 26 CPF RulemakingColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treasurer Stapleton Calendar May-July 2016Dokument14 SeitenTreasurer Stapleton Calendar May-July 2016Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage 2016 Part 5Dokument95 Seiten2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage 2016 Part 5Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Re: Draft Position Statement Regarding Home Rule Municipalities Ethics CodesDokument10 SeitenRe: Draft Position Statement Regarding Home Rule Municipalities Ethics CodesColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 2Dokument164 Seiten2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 2Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- CO Ethics Watch 2016session3 Part I PDFDokument100 SeitenCO Ethics Watch 2016session3 Part I PDFColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 4Dokument96 Seiten2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 4Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem and Mileage Part 3Dokument100 Seiten2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem and Mileage Part 3Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crowley County Ethics PolicyDokument2 SeitenCrowley County Ethics PolicyColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 1Dokument130 Seiten2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 1Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1876 Vermont Vote For PresidentDokument18 Seiten1876 Vermont Vote For PresidentJohn MNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ratification Process of The Us Constitution PowerpointDokument26 SeitenRatification Process of The Us Constitution Powerpointapi-267189291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Goodlatte Smith Letter To Speaker Johnson - Dec 8, 2023Dokument2 SeitenGoodlatte Smith Letter To Speaker Johnson - Dec 8, 2023Breitbart NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jefferson Vs Hamilton ThesisDokument5 SeitenJefferson Vs Hamilton Thesisbsgyhhnc100% (2)

- 898 F.2d 146 Unpublished Disposition: United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDokument3 Seiten898 F.2d 146 Unpublished Disposition: United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solution Manual For Managerial Accounting 2nd Edition Ramji Balakrishnan Konduru Sivaramakrishnan Geoff SprinkleDokument34 SeitenSolution Manual For Managerial Accounting 2nd Edition Ramji Balakrishnan Konduru Sivaramakrishnan Geoff Sprinkleenviecatsalt.ezeld100% (53)

- Eouch-Rt Dr-2: Be 'X A NN Tvae - Kglis Local JJ Crfcfy ( - For Office Use Ifviportan I': of You ForDokument16 SeitenEouch-Rt Dr-2: Be 'X A NN Tvae - Kglis Local JJ Crfcfy ( - For Office Use Ifviportan I': of You ForZach EdwardsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abcde: Trump Donor Met Putin Ally in SecretDokument56 SeitenAbcde: Trump Donor Met Putin Ally in SecretНаранЭрдэнэNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jim Crow LawsDokument26 SeitenJim Crow Lawsapi-360214145Noch keine Bewertungen

- NBCWSJ January Poll (1!19!18 Release)Dokument22 SeitenNBCWSJ January Poll (1!19!18 Release)Carrie DannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guide To School PrivatizationDokument18 SeitenGuide To School Privatizationtonybony585960Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mainstream Media Accountability Survey - Donald J Trump For PresidentDokument8 SeitenMainstream Media Accountability Survey - Donald J Trump For PresidentJoy-Ann ReidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6: Voters and Voter Behavior Section 1Dokument58 SeitenChapter 6: Voters and Voter Behavior Section 1Leo GonellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instant Download Enduring Vision A History of The American People 8th Edition Boyer Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDokument32 SeitenInstant Download Enduring Vision A History of The American People 8th Edition Boyer Solutions Manual PDF Full Chapterdrtonyberrykzqemfsabg100% (6)

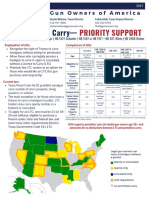

- Texas Constitutional Carry Priority SupportDokument2 SeitenTexas Constitutional Carry Priority SupportAmmoLand Shooting Sports NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gehry Statement of SupportDokument1 SeiteGehry Statement of SupporttimothydrichardsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study On Abraham LincolnDokument13 SeitenCase Study On Abraham LincolnDarshan VadherNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Government and Politics Deliberation Democracy and Citizenship 2nd Edition Bessette Test Bank 1Dokument14 SeitenAmerican Government and Politics Deliberation Democracy and Citizenship 2nd Edition Bessette Test Bank 1michael100% (28)

- Civil Rights Article 900 - 1100 DuckstersDokument3 SeitenCivil Rights Article 900 - 1100 DuckstersJohn JonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee - WikipediaDokument24 SeitenStudent Nonviolent Coordinating Committee - WikipediadwrreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ted Cruz Essay 1Dokument4 SeitenTed Cruz Essay 1api-375227307Noch keine Bewertungen

- Key Events of The Civil Rights MovementDokument3 SeitenKey Events of The Civil Rights Movementapi-349096142100% (1)

- Unit 11 Study GuideDokument1 SeiteUnit 11 Study Guideunknown racerx50Noch keine Bewertungen

- Siena Research Poll 8-15-16Dokument5 SeitenSiena Research Poll 8-15-16News 8 WROCNoch keine Bewertungen

- All House Committees Shall Be Chaired by Republicans and ShallDokument10 SeitenAll House Committees Shall Be Chaired by Republicans and ShallBrandon WaltensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Veritas Political Action Committee - 9804 - DR1 - 07-22-2010Dokument1 SeiteVeritas Political Action Committee - 9804 - DR1 - 07-22-2010Zach EdwardsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The McCarran-Walter ACT of 1952Dokument2 SeitenThe McCarran-Walter ACT of 1952dennis ridenourNoch keine Bewertungen

- Causes of The Civil War Graphic OrganizerDokument3 SeitenCauses of The Civil War Graphic Organizerapi-252230942Noch keine Bewertungen

- Top 60 Red Pilled Patriots - B2T ShowDokument6 SeitenTop 60 Red Pilled Patriots - B2T ShowVictor Herrera100% (1)

- How Important Was MLK To The Civil Rights MovementDokument11 SeitenHow Important Was MLK To The Civil Rights MovementMian Ali RazaNoch keine Bewertungen