Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1763-1973 H. G. Wells: Preacher and Prophet: The Pattern of Prediction

Hochgeladen von

Manticora Venerabilis0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

41 Ansichten5 SeitenThe decade between 1895 and 1905 marks the first main phase of crystallisation in the history of social and technological forecasting. The general sense of living at the end of the first great epoch of technological civilisation precipitated widespread curiosity about the pattern of technological change.

Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Futures Volume 2 Issue 3 1970 [Doi 10.1016%2F0016-3287%2870%2990031-5] I.F. Clarke -- The Pattern of Prediction 1763–1973- H.G. Wells- Preacher and Prophet

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThe decade between 1895 and 1905 marks the first main phase of crystallisation in the history of social and technological forecasting. The general sense of living at the end of the first great epoch of technological civilisation precipitated widespread curiosity about the pattern of technological change.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

41 Ansichten5 Seiten1763-1973 H. G. Wells: Preacher and Prophet: The Pattern of Prediction

Hochgeladen von

Manticora VenerabilisThe decade between 1895 and 1905 marks the first main phase of crystallisation in the history of social and technological forecasting. The general sense of living at the end of the first great epoch of technological civilisation precipitated widespread curiosity about the pattern of technological change.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 5

The Pattern of Prediction 269

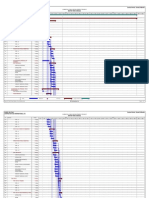

In all, we plan to have a model with

approximately 32 sectors on the pro-

duction side. Thus we shall have 32 wage

rate equations, 32 production functions,

32 hours worked equations, 32 price

equations and 32 final demand regres-

sions. These changes alone will add

approximately 150 equations to an al-

ready large model. Corresponding to

these changes on the side of production,

we shall make similar decompositions on

the side of final demand. We would want

32 investment functions in order to

build up 32 series on capital stock for the

32 production functions. We would also

need 32 depreciation equations. The

final demand regressions will be im-

proved if we make these and similar

decompositions of other types of final

demand. Foreign trade, consumption

and inventories will probably be further

decomposed . . . We shall probably end

up with a system of approximately 300 to

400 equations . . . Pp. 31-32

3. I have written of the post-industrial

society in a number of essays. The most

comprehensive statement can be found

in my monograph, The Measurement

of Knowledge and Technology, in

Indicators of Social Change, edited by

Eleanor Sheldon and Wilbert Moore

(Russel Sage Foundation, 1968)

The Pattern of Prediction 1763-1973

H. G. WELLS: PREACHER

AND PROPHET

I. F. Clarke

Of the many writers talking about the future state of society at the turn of the

century, most are now forgotten. However, H. G. Wells stands out more than

any of his contemporaries in making men aware of the urgent and complex

problems thrown up by continued technological development.

THE decade between 1895 and 1905

marks the first main phase of crystal-

lisation in the history of social and

technological forecasting. In those years

the earliest exercises in predicting the

future state of society began to appear

in print. And in this development there

were certain discernible factors at work.

First, the general sense of living at the

end of the first great epoch of tech-

nological civilisation precipitated wide-

spread curiosity about the pattern of

Professor I. F. Clarke is Head of the English

vtuies Department, University of Strathclyde,

life in the coming century. Second, this

interest coincided with the marked

increase in the numbers of science-based

stories and utopian visions of the

future that were published during the

1890s. Third-and most important of

all-the genius of H. G. Wells gave the

age an entirely new literature of

fantasies and factual predictions that

looked into the most varied possibilities

in science and in society.

Wells, however, was not alone. He

was the best of an increasing number of

authors who had taken to writing

about the future state of society. For

FUTURES September 1970

270 The Pattern of Predictions

instance, in Laings Problems of the

Future (1893) there were studies of the

expectation of peace in Europe, the

reorganisation of the tax system, the

problems of population and food sup

ply. Again, in Edward Carpenters

Forecasts of the Coming Century (1897)

ten writers (William Morris, Shaw,

Grant Alien and others) provided a

socialist analysis of the means and

methods of establishing a happier state

of society. Similarly, in Arthur

Brehmers Die We& in hmdert Jahren

(1904) a number of scholars, scientists,

and inventors gave their views on

matters as different as the future of

war and the role of women in the

twenty-first century.

They are all forgotten now; but

Wells is remembered for the startling

accuracy of so many of his forecasts.

In the matter of armoured warfare,

for example, Wells was right and the

General Staffs of the European armies

were all hopelessly wrong. In 1915,

when Colonel Swinton and Winston

Churchill pressed for the construction

of armoured trench-crossing machines,

the Engineer-in-Chief of the British

Army brushed off the proposition.

Before considering this proposal, he

said disdainfully, we should descend

from the realms of imagination to solid

facts. One year later the first tanks

had gone into action in France, and

they had fought in the way Wells

described in a short story, The Land

Ironclads, first published in 1903.

In this there seems to be a lesson for

technological forecasters, since the

characteristic Wellsian prediction de-

pended in equal measure on fact and

imagination. The earliest suggestion of

armoured fighting vehicles appeared in

the War of the Worlds (1898) ; and from

this simple exercise of the imagination

Wells went on to make a close study of

future developments in modern warfare.

He argued that, given the great

increase in fire-power, it would be

essential to protect the fighting man:

Experiments will probably be made

in the direction of armoured guns,

armoured search-light carriages and

armoured shelters for men that will

admit of being pushed forward over

rifle-swept ground. With admirable

logic Wells continued-to possibilities

even of a sort of land ironclad my

inductive reason inclines. These were

the solid facts on which he based his

imaginative account of armoured war-

fare in The Land Ironclad?.

The Wellsian forecast was the pro-

duct of reason and imagination-the

scientists capacity for logical analysis

and the artists gift for seeing con-

nections, possibilities, applications.

Wells developed these gifts throughout

his writing, led by a dominant interest

in society, spurred on by his angry

resentment at the dismal negligence of

the social and religious organisations

which had flung him into the world

misinformed, undernourished and

physically under-developed. He ques-

tioned the basic principles, the structure

and the organisation of his society.

His nagging doubts and his shrewd

insights were so native to his thinking

that they provided the framework for

utopian blue-prints and comic stories

alike. In describing the adventures of

his Cockney hero in K;pPs it was natural

for him to observe that man is a social

animal with a mind nowadays that

goes round the globe, and a community

cannot be happy in one part and

unhappy in another. That theme

reappears in The War in the Air, where

Wells points out that scientific develop-

ments had brought men nearer to-

gether, so much nearer socially and

physically and economically that the

old separation into nations and king-

doms are no longer possible.

Wells scattered these observations

throughout his books; and in this way

he did more than any of his contem-

poraries to make men aware of the

urgent, complex problems thrown up by

continued technological development.

He was the preacher and prophet of his

age, for in questioning the ways of

FUTURES September 1970

The P&em of Prediction 271

Figure 1. The first tank in history: the illustration for Wellss forecast of land ironclads in the

short story of that name in the Strand Magazine in 1903.

Figure 2. Infantry surrender to tanks:

consider the comment of Kitchener

on seeing the first real tank-la pretty

mechanical toy.

Sfieculations in Hard and Soft Science 273

society he was always ready with his

own answers. His best answers were

also his first-the collection of essays

published under the title of Anticipations

in 1901. In its way the book is one of

the historical landmarks of the twen-

tieth century: it was the first major

attempt to examine new trends in

society; it provided the model for its

kind; and Wellss world reputation did

much to encourage the practice of

preparing for anticipated changes.

Wells was the preacher and prophet

of his age. In Anticipations he had

studied the factors making for change

in locomotion, the size of cities, warfare,

communications, and social affairs.

He predicted the end of horse-drawn

transport and the coming of the

motor truck for heavy traffic. He

went on to argue that, because means

of transportation would increase and

population would grow, the whole of

Great Britain would become an urban

region held together by a new road

system, a dense network of telephones

and tubes for parcel delivery. He was

even more accurate when he came to

his chapter on warfare. He predicted

that the twentieth century state would

take over the direction of the civil

population in time of war, because

mass conscription required the total

mobilisation of industry. He foresaw

the importance of the air arm: Once

the command of the air is obtained by

one of the contending armies, the

war must become a conflict between a

seeing host and one that is blind.

And so he continued through the

twentieth century-deducing, proph-

esying, arguing. He was the first of the

modern-style forecasters. There has

never been anyone like him.

Speculations in Hard and Soft Science

Irving John Good

In this third instalment of the series, the author pursues his theme that ideas

that can not as yet be made practicable should be recognised as such and made

public. He lists some of his own partly baked ideas and invites similar contri-

butions from readers.

THE previous articles have shown that

an idea can have various degrees of

bakedness and it is not necessarily dis-

paraging to describe an idea as partly

baked: it is merely ambiguous. All

ideas are partly baked but some are less

baked than others. It is not the baked-

ness of an idea that makes it indigestible

but rather the pretence that it is more

baked than it really is. The estimate of

the digestibility depends on who has the

idea; the ideas that you incompletely

I. J. Good is University Professor of Statistics,

Virginia Polytechnic Institute, USA.

cook for yourself seem more digestible

than those of another chef.

Among professional scientists specu-

lations are often put forward apologeti-

cally if at all, and in 1952, F. A. Hayek

said : It seems almost as if specula-

tion (which, be it remembered, is

merely another name for thinking) has

become so discredited among psycho-

logists that it has to be done by out-

siders who have no professional reputa-

tion to lose. (The Sensory Order, p. vi.)

I speculate, therefore I am.

During the last year I have collected

FUTURES Sept ember 1970

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and ThoughtVon EverandAnticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and ThoughtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Futures Volume 7 Issue 6 1975 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (75) 90007-5) I.F. Clarke - 9. Ideal Worlds and Ideal Wars - 1870-1914Dokument6 SeitenFutures Volume 7 Issue 6 1975 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (75) 90007-5) I.F. Clarke - 9. Ideal Worlds and Ideal Wars - 1870-1914Manticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pattern of Prediction 1763-1973 The Predictive Utopia, 1871-1914Dokument5 SeitenThe Pattern of Prediction 1763-1973 The Predictive Utopia, 1871-1914Manticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- To Boldly Go: Leadership, Strategy, and Conflict in the 21st Century and BeyondVon EverandTo Boldly Go: Leadership, Strategy, and Conflict in the 21st Century and BeyondJonathan KlugNoch keine Bewertungen

- Osiris, Volume 34: Presenting Futures Past: Science Fiction and the History of ScienceVon EverandOsiris, Volume 34: Presenting Futures Past: Science Fiction and the History of ScienceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Futures Volume 8 Issue 1 1976 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (76) 90098-7) I.F. Clarke - 10. The Image of The Future - 1776-1976Dokument5 SeitenFutures Volume 8 Issue 1 1976 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (76) 90098-7) I.F. Clarke - 10. The Image of The Future - 1776-1976Manticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- H. G. WELLS: WHAT IS COMING?: A Forecast of Things after the 1st World WarVon EverandH. G. WELLS: WHAT IS COMING?: A Forecast of Things after the 1st World WarNoch keine Bewertungen

- HG WellsDokument16 SeitenHG Wellscruel foolNoch keine Bewertungen

- What is Coming?: A Forecast of Things After the War (1916)Von EverandWhat is Coming?: A Forecast of Things After the War (1916)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cutting Through History: Hayden White, William S. Burroughs, and Surrealistic Battle Narratives David LeesonDokument31 SeitenCutting Through History: Hayden White, William S. Burroughs, and Surrealistic Battle Narratives David LeesonValeriaTellezNiemeyerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Imperial nostalgia: How the British conquered themselvesVon EverandImperial nostalgia: How the British conquered themselvesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (2)

- Futures Volume 8 Issue 4 1976 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (76) 90131-2) I.F. Clarke - 13. Science and Society - Prophecies and Predictions 1840-1940Dokument7 SeitenFutures Volume 8 Issue 4 1976 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (76) 90131-2) I.F. Clarke - 13. Science and Society - Prophecies and Predictions 1840-1940Manticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian RevolutionVon EverandThe Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian RevolutionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Studies In The Napoleonic WarsVon EverandStudies In The Napoleonic WarsBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (3)

- Washington and the Hope of Peace; Or, Washington and the Riddle of PeaceVon EverandWashington and the Hope of Peace; Or, Washington and the Riddle of PeaceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cold Steel, Weak Flesh Mechanism, Masculinity and The Anxieties of Late Victorian EmpireDokument27 SeitenCold Steel, Weak Flesh Mechanism, Masculinity and The Anxieties of Late Victorian Empirelobosolitariobe278Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mapping the Millennium: Behind the Plans of the New World OrderVon EverandMapping the Millennium: Behind the Plans of the New World OrderBewertung: 1 von 5 Sternen1/5 (1)

- Emblems of Pluralism: Cultural Differences and the StateVon EverandEmblems of Pluralism: Cultural Differences and the StateNoch keine Bewertungen

- What is Coming? A Forecast of Things After the War (The original unabridged edition)Von EverandWhat is Coming? A Forecast of Things After the War (The original unabridged edition)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Perry Anderson, The Figures of DescentDokument58 SeitenPerry Anderson, The Figures of DescentDavid LyonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Conflict of Religions in the Early Roman EmpireVon EverandThe Conflict of Religions in the Early Roman EmpireNoch keine Bewertungen

- World Classics Library: H. G. Wells: The War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man, The First Men in the Moon, The Time MachineVon EverandWorld Classics Library: H. G. Wells: The War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man, The First Men in the Moon, The Time MachineBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (106)

- The New Monuments and the End of Man: U.S. Sculpture between War and Peace, 1945–1975Von EverandThe New Monuments and the End of Man: U.S. Sculpture between War and Peace, 1945–1975Noch keine Bewertungen

- Broken Soldiers: Serving As Public BodiesDokument14 SeitenBroken Soldiers: Serving As Public BodiesRuth Calvo IzazagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Development of the European Nations, 1870-1914 (5th ed.)Von EverandThe Development of the European Nations, 1870-1914 (5th ed.)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Futures Volume 7 Issue 3 1975 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (75) 90068-3) I.F. Clarke - 7. The Calculus of Probabilities, 1870-1914Dokument6 SeitenFutures Volume 7 Issue 3 1975 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (75) 90068-3) I.F. Clarke - 7. The Calculus of Probabilities, 1870-1914Manticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Visions of Empire: How Five Imperial Regimes Shaped the WorldVon EverandVisions of Empire: How Five Imperial Regimes Shaped the WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pattern of Prediction 1763-1973 A N X I O U S Anticipations: 1918-1939Dokument5 SeitenThe Pattern of Prediction 1763-1973 A N X I O U S Anticipations: 1918-1939Manticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- The People's Flag: The Union of Britain and the Kaiserreich: The People's Flag, #1Von EverandThe People's Flag: The Union of Britain and the Kaiserreich: The People's Flag, #1Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3)

- The Outline of History: Volume 2 (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): The Roman Empire to the Great WarVon EverandThe Outline of History: Volume 2 (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): The Roman Empire to the Great WarNoch keine Bewertungen

- University of Pennsylvania PressDokument21 SeitenUniversity of Pennsylvania PressmecawizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salient Features of The Victorian AgeDokument7 SeitenSalient Features of The Victorian AgeTaibur Rahaman80% (5)

- The Generals' Civil War: What Their Memoirs Can Teach Us TodayVon EverandThe Generals' Civil War: What Their Memoirs Can Teach Us TodayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pattern of Prediction 1763-1973 H. G. Wells: Exponent OF ExtrapolationDokument5 SeitenThe Pattern of Prediction 1763-1973 H. G. Wells: Exponent OF ExtrapolationManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- (THBN 14) Byron - Cain and Abel in Text and Tradition PDFDokument274 Seiten(THBN 14) Byron - Cain and Abel in Text and Tradition PDFCvrator MaiorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kennet Granholm - Dark EnlightenmentDokument243 SeitenKennet Granholm - Dark EnlightenmentJoseph Evenson100% (15)

- 10 1163@9789004330269 PDFDokument265 Seiten10 1163@9789004330269 PDFManticora Venerabilis100% (1)

- 10 1163@9789004343047 PDFDokument527 Seiten10 1163@9789004343047 PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schuchard2011 PDFDokument824 SeitenSchuchard2011 PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avi Hurvitz Leeor Gottlieb, Aaron Hornkohl, Emmanuel Mastéy A Concise Lexicon of Late Biblical Hebrew Linguistic Innovations in The Writings of The Second Temple Period PDFDokument281 SeitenAvi Hurvitz Leeor Gottlieb, Aaron Hornkohl, Emmanuel Mastéy A Concise Lexicon of Late Biblical Hebrew Linguistic Innovations in The Writings of The Second Temple Period PDFManticora Venerabilis80% (5)

- Text-Critical and Hermeneutical Studies in The Septuagint PDFDokument511 SeitenText-Critical and Hermeneutical Studies in The Septuagint PDFManticora Venerabilis100% (1)

- APR 002 Dodson, Briones (Eds.) Paul and Seneca in Dialogue PDFDokument358 SeitenAPR 002 Dodson, Briones (Eds.) Paul and Seneca in Dialogue PDFManticora Venerabilis100% (1)

- Farkas Gábor Kiss - Performing From Memory and Experiencing The Senses in Late Medieval Meditative Practice PDFDokument34 SeitenFarkas Gábor Kiss - Performing From Memory and Experiencing The Senses in Late Medieval Meditative Practice PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Brill's Companions To The Christian Tradition) Matthias Riedl - A Companion To Joachim of Fiore (2017, Brill Academic Pub) PDFDokument371 Seiten(Brill's Companions To The Christian Tradition) Matthias Riedl - A Companion To Joachim of Fiore (2017, Brill Academic Pub) PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- William Arnal - The Collection and Synthesis of 'Tradition' and The Second-Century Invention of Christianity - 2011 PDFDokument24 SeitenWilliam Arnal - The Collection and Synthesis of 'Tradition' and The Second-Century Invention of Christianity - 2011 PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- APR 001 Klostengaard Petersen - Religio-Philosophical Discourses in The Mediterranean World - From Plato, Through Jesus, To Late Antiquity PDFDokument428 SeitenAPR 001 Klostengaard Petersen - Religio-Philosophical Discourses in The Mediterranean World - From Plato, Through Jesus, To Late Antiquity PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slgean2016 PDFDokument300 SeitenSlgean2016 PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- New History of The Sermon 004 - Preaching, Sermon and Cultural Change in The Long Eighteenth Century PDFDokument430 SeitenNew History of The Sermon 004 - Preaching, Sermon and Cultural Change in The Long Eighteenth Century PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeffrey L. Powell - Heidegger and The Communicative World PDFDokument17 SeitenJeffrey L. Powell - Heidegger and The Communicative World PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rodolphe Gasché - The 'Violence' of Deconstruction PDFDokument22 SeitenRodolphe Gasché - The 'Violence' of Deconstruction PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Charles E. Scott - Words, Silence, Experiences - Derrida's Unheimlich Responsibility PDFDokument20 SeitenCharles E. Scott - Words, Silence, Experiences - Derrida's Unheimlich Responsibility PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- BDDT 081 Côté, Pickavé (Eds.) - A Companion of James of Viterbo 2018 PDFDokument442 SeitenBDDT 081 Côté, Pickavé (Eds.) - A Companion of James of Viterbo 2018 PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- VIATOR - Medieval and Renaissance Studies Volume 01 - 1971 PDFDokument354 SeitenVIATOR - Medieval and Renaissance Studies Volume 01 - 1971 PDFManticora Venerabilis100% (1)

- Richard Kearney - Returning To God After God - Levinas, Derrida, Ricoeur 2009 PDFDokument20 SeitenRichard Kearney - Returning To God After God - Levinas, Derrida, Ricoeur 2009 PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Journal of Medieval Monastic Studies - 003 - 2014 PDFDokument156 SeitenThe Journal of Medieval Monastic Studies - 003 - 2014 PDFManticora Venerabilis0% (1)

- Robert Bernasconi - Must We Avoid Speaking of Religion - The Truths of Religions 2009 PDFDokument21 SeitenRobert Bernasconi - Must We Avoid Speaking of Religion - The Truths of Religions 2009 PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Journal of Medieval Monastic Studies - 001 - 2012 PDFDokument169 SeitenThe Journal of Medieval Monastic Studies - 001 - 2012 PDFManticora VenerabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Indian MusalmansDokument139 SeitenThe Indian MusalmansSani Panhwar100% (2)

- Test 10Dokument4 SeitenTest 10phu dinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Liberian Civil War From 1989 Until 1996Dokument8 SeitenFirst Liberian Civil War From 1989 Until 1996moschubNoch keine Bewertungen

- BERBER Warriors (Antiquity - Middle Ages) PDFDokument45 SeitenBERBER Warriors (Antiquity - Middle Ages) PDFPiero GiuseppeNoch keine Bewertungen

- GCACW Series Rules 1.3Dokument24 SeitenGCACW Series Rules 1.3Adhika WidyaparagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Victims, Heroes, Survivors: Sexual Violence On The Eastern Front During World War IIDokument411 SeitenVictims, Heroes, Survivors: Sexual Violence On The Eastern Front During World War IIPaul Timms100% (3)

- Crochet Cowl PatternDokument1 SeiteCrochet Cowl PatternducamorisNoch keine Bewertungen

- "The Action Was Renew.d With A Very Warm Canonade" New Jersey Officer's Diary, 21 June 1777 To 31 August 1778Dokument58 Seiten"The Action Was Renew.d With A Very Warm Canonade" New Jersey Officer's Diary, 21 June 1777 To 31 August 1778John U. Rees100% (1)

- Elvis Presley - A Biography (Greenwood Biographies) (PDFDrive)Dokument161 SeitenElvis Presley - A Biography (Greenwood Biographies) (PDFDrive)Nova KillNoch keine Bewertungen

- 136.ICICI-Comprehenssive Commercial Vehicles PolicyDokument10 Seiten136.ICICI-Comprehenssive Commercial Vehicles Policyaloksemail2011Noch keine Bewertungen

- Caballero, Krizah Marie C. Bsma 2e Pe 3 Module 5 ActivitiesDokument3 SeitenCaballero, Krizah Marie C. Bsma 2e Pe 3 Module 5 ActivitiesKrizahMarieCaballeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zinky Boys - Svetlana AlexievichDokument233 SeitenZinky Boys - Svetlana Alexievichligia100% (1)

- 1Dokument7 Seiten1Jobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Free Exam PapersDokument67 SeitenFree Exam Paperscabojandi100% (1)

- E SpyDokument98 SeitenE SpyceedgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Criminal Court: Memorial For The ProsecutionDokument19 SeitenInternational Criminal Court: Memorial For The ProsecutionJoseLuisBunaganGuatelara100% (1)

- Esi BodyguardDokument24 SeitenEsi Bodyguarddoctorwolf64100% (2)

- WeaponsDokument29 SeitenWeaponsDiego VarelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- M.ed MithileshDokument104 SeitenM.ed MithileshrahulprajapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timeline ActivityDokument2 SeitenTimeline ActivityMary Ann MeineckeNoch keine Bewertungen

- CBCP Monitor Vol. 17 No. 8Dokument20 SeitenCBCP Monitor Vol. 17 No. 8Areopagus Communications, Inc.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Laundry Ebookv 2Dokument289 SeitenLaundry Ebookv 2Colin Barker100% (6)

- Abstract Under The Maternity Benefit Act, 1961 (Hindi Version)Dokument1 SeiteAbstract Under The Maternity Benefit Act, 1961 (Hindi Version)Vishwash Goyal100% (1)

- AP D80 Imperialism in AfricaDokument5 SeitenAP D80 Imperialism in AfricaChad HornNoch keine Bewertungen

- War, Democracy and Culture in Classical Athens PDFDokument13 SeitenWar, Democracy and Culture in Classical Athens PDFStella AntoniouNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Life & Achievements of Sir Arthur CurrieDokument9 SeitenThe Life & Achievements of Sir Arthur CurrieevaporateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zubair Oil Field Development Project-Master Time ScheduleDokument7 SeitenZubair Oil Field Development Project-Master Time ScheduleAbhinav SinhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument6 SeitenAnnotated BibliographyEricNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Berlin-Tokyo Axis and Japanese Military InitiativeDokument29 SeitenThe Berlin-Tokyo Axis and Japanese Military InitiativeLorenzo Fabrizi100% (1)

- 7.62 Base Walkthrough.V1Dokument43 Seiten7.62 Base Walkthrough.V1Kurwa KatyńskaNoch keine Bewertungen