Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ic1-Ic5 Interaction (Text)

Hochgeladen von

pinoros0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

49 Ansichten31 SeitenA tendency to emphasise interval-classes 1 and 5 is common in Shostakovich's later works. Pitch structures highlighting these interval classes occur in pieces from all phases of his career. Ic1 and ic5 underpin both the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the music.

Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenA tendency to emphasise interval-classes 1 and 5 is common in Shostakovich's later works. Pitch structures highlighting these interval classes occur in pieces from all phases of his career. Ic1 and ic5 underpin both the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the music.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

49 Ansichten31 SeitenIc1-Ic5 Interaction (Text)

Hochgeladen von

pinorosA tendency to emphasise interval-classes 1 and 5 is common in Shostakovich's later works. Pitch structures highlighting these interval classes occur in pieces from all phases of his career. Ic1 and ic5 underpin both the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the music.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 31

1

Ic1/Ic5 Interaction in the Music of Shostakovich

Introduction

Several analysts have observed in Shostakovichs later works a certain focusing of pitch

resources, in particular, a tendency to emphasise interval-classes 1 and 5, both singly and in

combination.

1

Though pitch structures highlighting these interval-classes are indeed common in

the music of Shostakovichs final years, they actually occur in pieces from all phases of his

career, as a few short examples can demonstrate. Ex. 1a quotes an excerpt from the First Piano

Sonata (1926), written when the composer was just twenty years old. The passage starts with an

emphatic scalar gesture framed by the ic1 dyad {F, F}. After several repetitions, this descending

gesture alternates with two ic5 dyads expressed as perfect fourths, the first one ascending (GC),

the second descending (BF). Ex. 1b more fully reveals the network of ic1 and ic5 relations

underlying the excerpt.

2

Ex. 2 shows an excerpt from mid-career: the opening of the second

movement of the Second Piano Sonata (1943). Here melody and accompaniment are both shaped

by ic1 and ic5. The right hand begins with an ic5-based, stacked-fourth trichord (GCF,

spelled upward), which descends twice by semitone, leading to a return of C, the lines starting

pitch. Meanwhile, the left hand begins with the vertical ic5 dyad {A, E}, from which the voice

leading relies exclusively on ic1 and ic5: the upper voice of the left-hand part traces the line A

A!B, the middle voice progresses from E to F, and the lower voice moves from A to D. Thus

ic1 and ic5 underpin both the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the music. Finally, Ex. 3a

excerpts a passage from the Fourteenth Symphony (1969), a crowning work of his late period.

Here the vibraphone solo unfolds a series of vertical ic5 dyads, some conveyed as perfect

2

fourths, the rest as perfect fifths. Factoring out octave displacements, a clear pattern emerges: a

palindrome of ic5 dyads, themselves related by ic1, as shown Ex. 3b. Again ic1/ic5 structure

underlies the passage.

3

Motivated by such examples, this study explores the interaction of ic1 and ic5 within the

context of the Shostakovichs multi-faceted tonal language, drawing on examples from

throughout his career. As we shall see, a focus on ic1/ic5 relations offers a way into much of

his music, an approach that can enrich our appreciation of both local detail and large-scale

organization. Along the way we will consider not only how ic1/ic5 interaction can shape a piece

on its own, but also how it connects to other aspects of design, even music/text relations. In

addition, we will see that an ic1/ic5 perspective can shed new light on previous Shostakovich

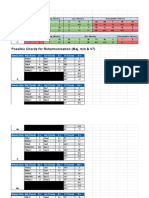

analysis, most notably that of Russian modal theorists.

Ic1/Ic5 Space and the Music of Shostakovich

The ic1/ic5 aspect of Shostakovichs music can often be illuminated through the

methodology of dual interval space (or DIS), a concept I have discussed elsewhere at length but

can summarise here.

4

A DIS is a two-dimensional pitch-class array, or Tonnetz, in which each

axis corresponds to a distinct interval-class. Since there are fifteen pairs of (distinct) interval-

classes, there are fifteen spaces. Ex. 4 shows the one combining interval-classes 1 and 5, a visual

representation of ic1/ic5 space.

5

Using operations in a DIS, we can relate pitch-class sets in

new ways, revealing musical symmetries beyond those associated with conventional pitch-class

operations. Ex. 5 provides two examples of flipping operations within ic1/ic5 space. Partial

inversion (shown in Ex. 5a) involves flipping about a horizontal or vertical axis (a vertical axis

3

in this case). Interval exchange (shown in Ex. 5b) entails flipping about either of the two

diagonal axes, thus swapping the component intervals (hence the name). In both cases, the

operations relate members of different set-classes.

6

On a more general level, a DIS can provide a framework for charting melodic and

harmonic processes, bringing them into sharper focus. As a case in point, Ex. 6 shows how

ic1/ic5 space can elucidate a musical process unfolding in a piece by Shostakovich. Part (a)

shows the opening of the Viola Sonata, his final work. Starting in bar 1, the viola establishes a

four-measure accompanimental pattern comprising a two-measure subphrase followed by a two-

measure variant. Reminiscent of Bergs Violin Concerto, the initial subphrase draws its pitch

content entirely from the violas four open strings. In the next two measures, the violas open C

progresses to its upper neighbour, D, and its open A to the C a minor third above; this C can be

heard as a displacement, two octaves higher, of the original low C. Starting in bar 5, the viola

repeats its pattern while the piano enters with a twelve-note melody in the right hand. Altogether,

the pitch content of the viola part forms a four-note segment of the circle of fifths, one of whose

terminal notes is embellished by a semitonal adjacency. Thus it can be depicted as a contiguous,

L-shaped region in ic1/ic5 space, as shown in Ex. 6b.

Near the end of the movement the viola plays a cadenza, which both synthesises and

extends the movements opening materials (see Ex. 6c). Starting in bar 222, the viola alternates

between two distinct melodic strands. One strand, comprising legato notes, repeats the pianos

original twelve-note melody in segments of either three or six notes. The other, staccato strand

derives from the violas opening accompanimental figure (see the brackets on the example).

Here, the viola extends its original accompanimental pattern by pairing each of its open strings

4

with its half-step upper neighbour, thus completing a process broached at the beginning of the

movement and thereby forging a long-range connection spanning nearly the entire movement.

Ex. 6d displays the resulting pitch structure in ic1/ic5 space. As it shows, what was once

asymmetrical has now become symmetricalin particular, symmetrical with respect to partial

inversion.

Ic1/Ic5 Interaction and Centricity

To more fully appreciate the role of ic1/ic5 interaction in Shostakovichs music, we need

to consider its relation to centricity. Though his music typically lacks traditional, functional

chord progressions, an individual passage often conveys a pitch-class centre, or tonic, through

various means. Chief among them are: 1) placing the tonic in the lowest register, 2) featuring it

at formal junctures (beginnings and endings of phrases, sections, and movements), and 3)

emphasizing it through various brute force methods, such as repetition and octave doubling. In

addition, Shostakovich usually reinforces a tonic by treating it as the root of a triad, i.e. by

supporting it with its upper third and/or upper fifth. Occasionally a supporting note lies below the

tonic, resulting in what would traditionally be called a I

6

or I@.

7

In Shostakovichs music, local tonics often provide the basis for ic1/ic5 structures. In the

music of Ex. 3, for instance, Shostakovich conveys E as tonic by sustaining it in the bass,

doubling it in several registers, and supporting it with its upper fifth; and sure enough, this pitch-

class (along with its upper fifth, an ic5 relative) serves as both the origin and goal of ic1/ic5

activity. The music of Ex. 2 presents a slightly more elaborate situation: the left-hand part

resembles the previous examples in that its ic1/ic5 activity originates with the tonic and

5

supporting upper fifth (A and E); in the right-hand part, however, the ic1/ic5 activity emanates

from C, the third of the tonic triad and centre of the initial stacked-fourth trichord. The music

thus offers a small but instructive example of ic1/ic5 interaction operating in conjunction with

another musical parameter: though the right- and left-hand parts can each be heard exclusively in

terms of ic1/ic5 interaction, their initial connection depends on the major third AC, an interval

that belongs to neither ic1 nor ic5, but instead derives from the tonic triad; the passage therefore

comprises two spheres of ic1/ic5 activity linked by the tonic triad from which they both emerge.

8

The music of Ex. 1 presents a contrasting situation, in which ic1/ic5 interaction occurs in the

absence of triadic elements or a clear tonic. Yet here, too, the music combines ic1/ic5 activity

with another element acting in conjunction with it: in this case, the white-note diatonic

collection, which serves to fill in the descending scalar gestures, composing out the FF

spanning intervals.

9

Finally, in the music of Ex. 6, the violas ic1/ic5 activity clearly originates

with C, the tonic. In contrast with the other examples, however, the pianos twelve-note melody

functions as an independent musical component, neither rooted in ic1/ic5 interaction nor strongly

connected to the violas ic1/ic5 activity.

10

Connections with Other Shostakovich Scholarship

As mentioned at the outset, several Western scholars have noted the significance of ic1

and/or ic5 in Shostakovichs music (though just in his late music). However, only one has

considered their interaction in any depthand in this case, only indirectly. In a study of the

Fifteenth Symphony, Peter Child explores Shostakovichs use of three closely-related set-

classes: 4-8[0156] and 4-9[0167], and their mutual subset, 3-5[016].

11

Ex. 7 shows a

6

representative instance from his article, in which set-class 4-9 underlies both a twelve-note

melody and its accompaniment. In discussing this theme (and a related one), Child observes that

Shostakovich deploys 4-9 as a pair of ic5 dyads linked by semitone. Yet he stops short of

identifying ic1 and ic5 as the essential building blocks, either here or in his other examples.

Thus, even though Child offers revealing examples of ic1/ic5 interaction, he acknowledges that

interaction only obliquely.

Nonetheless, recognizing the generative role of ic1 and ic5 can lead to a fuller reading of

the passage. For example, Child observes that within each half of the melody, a perfect fourth

defines the registral boundaries: {B, E} in the first half of the melody and {E, A} in the second,

as shown in the top line of his example. Yet these boundaries enclose two sorts of ic1 activity:

the first half of the melody wedges outward chromatically from {C, C!}, through {D, B}, to {E,

B} (the registral frame), while the second half descends mostly chromatically (were it not for the

swapping of F and G in the middle of the phase).

12

Within the melody, therefore, ic5 provides

the registral frames, and ic1 the means for elaborating them.

Ic1/ic5 interaction also connects melody and accompaniment. In the first subphrase, the

accompaniments ic5 dyad {E, B} relates by ic1 to {E, B}, the ic5 dyad underlying the melody;

and in the second subphrase, the accompaniments {B, F} relates by ic1 to the {A, E}

underlying the melody. Finally, if we step back to consider the whole framework supporting both

melody and accompaniment, we find that the entire hexachord (formed by combining Childs

two 4-9s) is in fact symmetrical with respect to interval exchange in ic1/ic5 space. Moreover, as

Ex. 8 shows, this symmetry can be interpreted as taking place about E, the local tonic.

7

The concept of ic1/ic5 interaction also engages work by Russian theorists on modality in

Shostakovichs music; and as with Childs study of the Fifteenth Symphony, an ic1/ic5 approach

can sometimes offer a way to enrich and extend their analyses. As Ellon Carpenter has discussed,

Russian modal theorists generally agree that Shostakovichs music is diatonically based.

13

This is not to say that his music always remains within diatonic collections, but rather, that it

normally derives from diatonicism in some way. For example, a passage might employ a diatonic

scale with chromatic alterations, or combine pitches drawn from multiple diatonic collections.

Moreover, Russian theorists acknowledge that Shostakovichs diatonicism (indeed, all

diatonicism) stems from a Pythagorean-derived quartal-quintal foundation.

14

Using the terms of

Anglo-American post-tonal theory, one might say therefore that Russian theorists consider ic5 a

basic constructive element in Shostakovichs music. Yet as our previous examples have

demonstrated, ic1 frequently plays a conspicuous role in conjunction with ic5. Thus the modes

and modal frameworks that Russian theorists identify in Shostakovichs music can often be

understood as resulting from ic1/ic5 interaction.

Consider the following example. Starting in the 1940s with the earliest work on modality

in Shostakovich, Russian theorists have recognised the significance of certain lowered modes in

his music. One such mode is Phrygian with lowered ^4, known as lowered Phrygian or

intensified Phrygian.

15

Like all scales involving the chromatic alteration of a diatonic mode,

this one could be interpreted as a product of ic1/ic5 interaction. As Ex. 9 shows, ic5 generates the

white-key collection of unaltered Phrygian (a seven-note segment of the circle of fifths spanning

from F to B), while ic1 is responsible for the downward inflection from A to A. Together with

lowered modes, Shostakovich scholars generally acknowledge the centrality of diminished

8

intervals in his music, especially the diminished fourth, which spans his musical motto, DEC

B (as well as the first four scale degrees of lowered Phrygian, which constitute the same

tetrachord type). Yet this interval so characteristic of Shostakovichs musical language could be

taken as the very embodiment of ic1/ic5 interaction: it results from a perfect fourth (ic5)

contracted by a semitone (ic1). True, it would be simpler to regard the interval merely as an

instance of ic4 (rather than a byproduct of ic1 and ic5), but this simplification (in essence,

lumping the diminished fourth together with the major third) ignores both the functional

significance of the interval (in terms of scale-degree relationships) and its peculiar expressivity.

For a more vivid illustration of these issues we can turn to the variation theme opening

the last movement of Shostakovichs Second Piano Sonata. Shown in Ex. 10, the theme divides

into three phrases, of nine, ten, and eleven bars, respectively (as marked in the score). In the first

phrase, perhaps the most strikingand certainly most Shostakovichianfeature of the melody is

its use of ^4 and ^ 8 (see bars 47). In her important study of mode in Shostakovich, V. Sereda

interprets these scale degrees as participating in two distinct melodic cells, or melodic

subsystems. In each case, a lowered degree forms the upper boundary of a melodic subsystem

spanning a diminished fourth, one built upward from ^1 (BCDE), the other built upward

from ^5 (FGAB).

16

Taken together, the four boundary notes of these two subsystems create a

framework rooted in ic1/ic5 interaction, as we can deduce from Seredas schema of bars 19

(the only part of the theme she discusses; see Ex. 11). Shown with open noteheads in her

diagram, B and F, the tonic and its supporting fifth, form an ic5 dyad that provides the main

grounding for bars 19. The upper boundaries of the two subsystems likewise form a perfect fifth

(i.e. another ic5 dyad), which Sereda brackets and labels 5. In addition, an ic1 dyad spans from

9

^1 to ^8, the outer limits of the subsystems. (Sereda subtly highlights this important interval by

verticalizing it on her diagram, and Shostakovich himself emphasises it as a direct melodic

succession in bar 6.) Finally, the remaining notes in Seredas schema, C! and A, both relate to

the tonic by ic1. Thus ic1/ic5 connections underlie her entire diagram.

Acknowledging this ic1/ic5 foundation provides a basis for further interpretation, both of

phrase 1 and of the entire theme. As for phrase 1, let us consider what the melody would be like

without chromatic alteration (that is, if it were pure Aeolian or natural minor). Were this the

case, the boundary intervals of the two melodic subsystems would be BE and FB. Together,

these notes form the ic5-based trichord {B, E, F} (sc 3-9[027]), which in fact Shostakovich

isolates at the outset of the melody, in bars 12. Yuri Tyulin, an important developer of Russian

modal theory, refers to a tonic and its two flanking fifths as a modal cell.

17

Hence the passage

begins with a simple, unadulterated modal cellthe embodiment of diatonicisms quartal/quintal

foundationwhich is then chromatically altered to form the underlying tetrachord {B, E, F,

B}, a member of sc 4-20[0158]. Ex. 12 summarises the process. In sum, one could say that ic5

underpins the generic, diatonic framework for the passage, while ic1 accounts for the chromatic

inflections that lend it its specific, Shostakovichian flavour. (These ideas emerge particularly

clearly if one plays bars 19 first without any chromatic alterations, then as written.)

On a larger level, an ic1/ic5 perspective can illuminate the sometimes surprising

harmonic moves underlying the rest of the melody. Depicted in the sketch of Ex. 13, these moves

could be summarised as follows: In bar 14 the melody slides upward to C as a local pitch centre,

then settles back on a B minor half cadence in bar 19; at the end of bar 20 the melody returns to

C, from which it progresses to B by a pattern of descending fifths; finally in bars 2223 the

10

melody regains the tonic with another upward slide, this time from B to B, balancing the earlier

move from B to C. In essence, then, Shostakovich bridges two reciprocal ic1 gestures (BC and

BB!) with ic5 motion (CFB). The latter, falling-fifth pattern is in fact foreshadowed at the

very outset of the melody, where it occurs as FBE within the opening statement of the

Tyulinian modal cell. Likewise the flanking-semitone pattern is encapsulated in bars 67 (B

C!AB), and again in bars 2829, in slightly modified form. These two motives serve as

contrasting tokens of the ic1 and ic5 dimensions underlying the theme, in that the opening modal

cell occupies a three-note segment of the circle of fifths, while the flanking-semitone pattern

conveys a three-note segment of the chromatic scale. And since each of these motives encloses

the tonic as its (pitch-class) inversional centre, they relate to each other by interval exchange,

with the tonic defining the axis of symmetry, as shown in Ex. 14.

For another illustration of how we can engage and expand upon a Russian reading of a

Shostakovich passage, let us consider an excerpt from the first movement of the Eighth

Symphony analysed by Eleonora Fedosova in her 1980 book on diatonic modes in

Shostakovichs music.

18

Ex. 15 quotes part of the expositions secondary theme area; Fedosova

discusses only the violin part in the first four bars. In keeping with her central premise, Fedosova

reveals the melodys diatonic basis by dividing it into two (diatonic) scale segments: a Phrygian

pentachord built upward from B, followed by a major pentachord built upward from F (see Ex.

16). Like Seredas diagram in our previous example, Fedosovas conveys an implicit ic1/ic5

framework. In this case, the framework combines two ic5 dyads (BF and F!C) linked by ic1

(FF!), forming a version of sc 4-9[0167]. One might recall that the same partitioning of 4-9 also

underpins the excerpt from the Fifteenth Symphony analysed by Child in Ex. 7 above. Thus,

11

while Fedosova and Child pursue contrasting approaches to Shostakovichs music, the notion of

ic1/ic5 interaction can illuminate the common ground between them. One might also observe

that the 4-9 of Fedosovas diagram also bears a close resemblance to the tetrachord underlying

the opening of the piano sonatas variation theme, since it, too, comprises two ic5 dyads

connected by ic1 (see Ex. 12); this time, the two tetrachords relate by partial inversion, as shown

in Ex. 17. Again, an ic1/ic5 approach can link the readings of two scholars analysing different

passages by Shostakovich.

As with the theme from the Piano Sonata, recognizing the ic1/ic5 basis of the Eighth

Symphony melody enables a fuller grasp of the passage, sensitizing us to further ic1/ic5

connections and allowing us to relate Fedosovas small excerpt to its larger surroundings. For

one example, consider the violin melody following the climax at bar 106. From here until the

second note of bar 109, the melody confines itself exclusively to ic1 and ic5. In fact, the melody

conveys a more specific pattern involving ic1 and ic5, namely, a series of ic5 dyads linked by

semitonal connections, as shown in Ex. 18. Near the end of this pattern (from the fourth beat of

bar 107 to the end of bar 108), the melody fixes upon the tetrachord {E, F, B, B!}, another

member of 4-9, the set-class that earlier underpinned the beginning of the violin melody (the part

that Fedosova analyses). Thus the violin line now distils and foregrounds both the general

intervallic principle (ic5 dyads linked by semitone) and ultimately, the specific tetrachord type

(set-class 4-9) that previously organised it on a middleground level.

Consider also the English horn/viola line, the cantus firmus of the passage. This melody

is equally dominated by ic1 and ic5; indeed, every one of its melodic adjacencies belongs to ic1

or ic5. It begins with the trichord DAB (spelled upward; see bars 9798), two transpositions

12

of which are embedded in the first part of the violin line (BFG twice in bars 9597, then FC

D in bars 9798). As the line unfolds, its initial cell provides the basis for its own transpositions:

if we take D as its origin, then the origins of its following two transpositions are none other

than its remaining two notes (that is, the melody moves to BFG in bars 99100, then AEF

in bars 101106).

19

Since each statement of the cell is built from overlapping ic1 and ic5 dyads

(DA and AB in the case of the first cell), it follows that ic1/ic5 interaction not only generates

the cell, but also governs its transpositions. As Ex. 19 shows, a small triangular region in ic1/ic5

space spawns a larger one; and therefore an ic1/ic5-based cell embedded in Fedosovas excerpt is

responsible for generating the entire cantus firmus of the passage.

Large-Scale Structure and Other Aspects of Musical Design

Thus far we have witnessed several small-scale instances of ic1/ic5 interaction in

Shostakovichs music; we have advanced the concept and methodology of dual interval space as

an aid to interpreting these passages; we have considered other approaches to Shostakovichs

music, both Western and Russian; and we have seen how an awareness of ic1/ic5 interaction and

the concept of ic1/ic5 space can help us to engage and even expand upon these approaches. Yet

two important questions remain. First, can the concept of ic1/ic5 interaction support readings of

longer passages, if not entire pieces or movements? Second, given that ic1/ic5 interaction

constitutes just one facet of Shostakovichs diverse tonal language, can it be embraced within a

discussion that also considers other aspects of a piece, rather than treating it as an isolated

component of the music? The remainder of this essay confronts these questions in varying

degrees by examining three pieces by Shostakovich in greater detail: the fifth of his Aphorisms

13

for piano, Op. 13 (1927), the first movement of the Twelfth String Quartet, Op. 133 (1968), and

the song Noch-Dialog [Night-Dialogue] from the Suite on Verses of Michelangelo, Op. 145

(1974). In discussing the first two pieces, we will focus on the issue of ic1/ic5 interaction and

large-scale structure, with some reference to how non-ic1/ic5 material can be incorporated within

an ic1/ic5-based reading. For the last piece, we will focus on how ic1/ic5 interaction can relate to

other aspects of design.

Written in the same year as the First Piano Sonata, the fifth of Shostakovichs Aphorisms

(Funeral March) features a modernistic idiom that the composer cultivated in the late 1920s

upon graduating from conservatory. Like The Nose, his major achievement of the period, the

piece infuses this modernistic idiom with elements of traditional tonality. Most notably, it is

framed by C major harmony (ironically, given its title). As we shall see, this framing harmony is

grounded within a global ic1/ic5 design that spans the entire piece. This design, however, does

not account directly for every last pitch. Thus we will have an opportunity to explore how the

ic1/ic5 aspect of organization relates to other components of structure.

Ex. 20 quotes the piece and divides it into three parts: an opening, fanfare-like section

(Part 1), the main body of the piece (Part 2), and a conclusion (Part 3). As the music unfolds, it

traverses the ic1/ic5 region shown in Ex. 21, which serves as the backbone for the piece. The

music progresses generally leftward through this region (and near the end, downward),

connecting the {C, G} of the initial tonic chord in bars 13 (located at the far right of the

diagram) with the {C, G} of the concluding tonic chord, reached in bar 29 (located at the bottom

left). In between, the music establishes the remainder of the region by emphasizing other ic1 and

ic5 dyads contained within it, as detailed below.

20

14

Part 1 initiates the overarching ic1/ic5 structure by staking out the 2 x 3 rectangular

region on the right-hand side of Ex. 21 (as marked on the diagram). This hexachord emerges

most prominently as a series of ic5 dyads descending by semitone, all expressed as perfect fifths

in the same register: C and G stand out as the most conspicuous notes of the opening C major

triad (grounding the tonic triad in the overarching ic1/ic5 design, as mentioned above), while the

vertical dyads {B, F} and {B, F!} fall on the downbeats of bars 6 and 8, respectively. Ex. 22a

provides a fuller picture of the hexachords unfolding: each line in the diagram begins when the

corresponding pitch-class is first introduced, and ends when it is last sounded; Ex. 22b realises

the diagram in musical notation.

Despite its prominence, the underlying hexachord does not embrace every note in Part 1.

In order to account for these remaining pitches, we have to acknowledge another source of

material in the passage. This third dimension (in addition to the ic1 and ic5 dimensions)

comprises scalar and triadic materials drawn from the C major diatonic collection, which

decorate the underlying ic1/ic5 structure. For instance, the E of bar 3 serves as a modal support

or triadic extension to C. Likewise the A and C of bar 5 can be interpreted as triadic extensions

of F, and G as a passing note connecting them.

21

As with Part 1, Part 2 projects a 2 x 3 region of the underlying structure, one that overlaps

with Part 1s region, as marked in Ex. 21. It does so by emphasising three dyads contained in the

region, each a member of ic1 or ic5: {A, B} recurs as a low drone throughout the entire section

(its location at the geographical centre of the entire diagram is appropriate given that it

dominates the centre of the piece); {E, F} combines with this drone in bars 2425, forming the

strongest expression of ic1/ic5 in the piece, an emphatic statement of two ic1 dyads related by

15

ic5; and {A, E} emerges quietly in bars 2223, then loudly in bars 2728, providing a

conspicuous ending to the section.

Compared with Part 1, Part 2 feels more loosely organised, and indeed a larger share of

its notes lies beyond its portion of the pieces overarching ic1/ic5 structure. Nonetheless, much

of its melodic material can be traced back to Part 1, and therefore stems ultimately from a

combination of ic1/ic5 interaction and C major diatonicism. For instance, the opening melodic

line of Part 2 (in bars 1011) derives from the left-hand part in bars 6!8; the subsequent CG

of the line (in bars 1213) refers back to the opening, tonic dyad; the vertical {G, F} of bar 13

recalls the downbeat of bar 4 (a connection bolstered by the return of the fanfare rhythm, now in

the upper voice); the right hands FCC! in bars 1314 derives from the opening melody in

bars 1, 2, and 4; the right-hand melody in bars 1415 restates the last three pitches struck in Part

1 (C, B, and F); and so forth. Shostakovich thus creates Part 2 to a large extent by drawing

flexibly on elements from Part 1, modifying and recombining them in the manner of a collage.

Part 3, finally, is underpinned by the return of C major harmony, which sounds

continually (save for a brief intrusion of Part 2 material in the penultimate bar) and which

provides closure to the pieces overarching ic1/ic5 structure. This chord combines with a

neighbouring Neapolitan harmony, which conveys the {D, A} of the underlying ic1/ic5

structure.

22

Together, the ic5 dyads underpinning the tonic and Neapolitan form a square region

in ic1/ic5 space, creating a version of set-class 4-8[0156] and tying Part 3 back to the climactic

ic1/ic5 moment of bars 2425, which also conveys a square ic1/ic5 tetrachord.

23

All pitches

in Part 3 outside of this square region (save for those in the intrusive penultimate measure) can

be accounted for in a similar manner as in Part 1; in this case, they all belong to C major or D

16

major diatonic collections that are clearly connected to the underpinning {C, G} and {D, A}

dyads.

As our discussion of the Funeral March demonstrates, the concept of ic1/ic5 interaction

can underlie the global reading of an entire piece, albeit a rather short one. For a large-scale,

ic1/ic5-based reading of a somewhat longer work, we can turn to the first movement of

Shostakovichs Twelfth String Quartet. Such is the prominence of ic1 and ic5 in this movement

that Hans Keller, in an early analysis, referred to them as its basic intervals.

24

In addition, the

movement features particularly striking contrasts of tonal and atonal materials. Yet ic1/ic5

interaction embraces and unites these disparate materials on both local and global levels.

For an instance of the former, we need look no further than the very opening of the

movement. Quoted in Ex. 23, the section epitomises the contrasts just noted: it begins with a

twelve-note row in the solo cello followed by a tonally functional passage in D major, the

overall tonality of the quartet.

25

Like the movement as a whole, the cellos row is dominated by

ic1 and ic5, which together account for eight of its intervallic adjacencies. The row culminates

with the notes BAD, which help to set up the following, tonal section by functioning as ^6

^5^1 within D major. In addition, these three notes combine to form an ic1/ic5 scaffolding for the

following, tonal section. As shown in the graph of Ex. 24, the dyad {D, A} provides the

harmonic basis for the passage, linking the two outer voices as tonic and supporting fifth;

meanwhile, the primary melodic feature is the upper voices ic1 neighbour gesture ABA.

(This gesture, in turn, is supported by the progression IivI, itself an ic5-based harmonic motion

that helps to balance the conspicuous dominant degree in the passage.) An ic1/ic5-based trichord

therefore provides the connective tissue linking the opening row and the following, tonal section.

17

A similar, ic1/ic5 trichord also underlies the entire movement. As summarised in Ex. 25,

the movement takes the form of a sonata with reversed recapitulation, progressing from tonic to

dominant in the exposition, then to the flat supertonic in the development (spelled as D!), and

finally back to the tonic for the (reversed) recapitulation. Ex. 26 depicts the movements large-

scale tonal structure, along with the trichordal scaffolding of the opening tonal section, showing

how they relate by partial inversion.

On closer inspection, the movements middleground tonal organization involves a

deeper level of ic1/ic5 interaction. In order to see this, let us first consider how Shostakovich

navigates from D major into the D minor of the development, and then, how he moves from

there back to D major. Shostakovichs first tonal move is the simplest: in order to get to the A

of the secondary theme area, he merely shifts focus from the tonic to its supporting fifth,

dropping out D and supporting A with its own upper fifth: an unelaborated, surface-level T

7

move, as shown in Ex. 27. Within the secondary theme area, the harmony is underpinned by a

series of two- and three-note sonorities played by the viola and cello, each one repeated, drone-

like, for four measures. Shown in Ex. 28, the harmonic progression bears a marked resemblance

to the left-hand part of Ex. 2 above: it begins with a vertical {A, E} dyad, and from hereif we

ignore the second chordall of the voice-leading involves pure semitonal motion (the voice

leading from the first chord to the second primarily involves ic5). Ic1 and ic5 also underlie the

progression on a broader level: as the boxes in the example show, the essential voice leading

entails the perfect fifth {A, E} contracting by semitone to the perfect fourth {A, D}, in

preparation for the D minor of the development. (In this connection we might note that

Shostakovich begins the development by maintaining the @ position of the D minor harmony,

18

placing A in the cello part.) In sum, an ic5 move links the main theme area to the secondary

theme area, while ic1-based voice leading links the secondary theme to the development.

The harmonic structure of the development is more elaborate. In essence, though, it is

underpinned by a T

5

move from the initial {A, D} to {D, G}, with {F, B} as an intermediate

stopping point, as shown in Ex. 29. (These three principal dyads are shown with open noteheads;

the concluding {D, G} joins with a low C in the cello, which functions both as Gs underfifth

and as leading note to D.) From here, the return to the home key involves a semitonal expansion

of the perfect fourth {D, G} into {D, A}, the opposite of the move that carried us into the

development. Summarised in Ex. 30, the overall tonal motion of the movement could therefore

be described as ascend by fifth, contract by semitone, descend by fifth, expand by semitone.

Thus far we have witnessed overarching, ic1/ic5-based models of pitch structure for two

contrasting pieces by Shostakovich: a short, early work, and a longer, late work. For our final

discussion, we will shift focus from the issue of global structure to the question of how ic1/ic5

interaction can relate to other facets of a piece. Though we have dealt with this question to some

extent already (for example, in discussing the fusion of ic1/ic5 interaction and C major

diatonicism in the opening of the Funeral March), we have yet to place it front and centreto

thematise it. With this as our goal we turn to the song Night-Dialogue from the Suite on

Words of Michelangelo, a piece that features an interesting mix of ic1/ic5 activity and

octatonicism.

At first, these two aspects of pitch structure might seem diametrically opposed. Unlike all

but one of the other eight-note set-classes, the octatonic is not connected relative to ic1 and ic5;

in other words, it is impossible to traverse a complete octatonic collection using only ic1 and ic5.

19

Ex. 31 illustrates the situation with a pitch-class graph of collection II, the main octatonic

collection used in the song.

26

As it shows, the collection divides into two separate components,

each a member of set-class 4-9.

Despite this seeming incompatibility, the octatonicism of the song stems directly from

ic1/ic5 activity, in a process that unfolds during the introduction. Ex. 32 quotes the passage and

divides it into three phrases. The first phrase opens with an oscillating gesture built on C, the

songs tonic, combined with G, its supporting upper fifth.

27

In bar 3, the gesture repeats,

followed by a variation based on semitonal neighbouring motion around G. As Ex. 33a

illustrates, the Gs wedge outward to A and F, then each of these neighbours spawns a new

note a perfect fourth away, yielding E and B; Ex. 33b displays the process within ic1/ic5 space.

The resulting neighbour chorda member of set-class 4-26clearly arises from ic1/ic5

activity. However, it is not connected relative to ic1 and ic5, but instead divides into two ic5

dyads related by ic3, as shown in Ex. 33c.

The ic3 relationship embodied by this neighbour chord creates the potential for

octatonicism, which emerges full-blown in the next phrase of the introduction. Isolated in Ex. 34,

this phrase is entirely octatonic, presenting 7 of the 8 pitch-classes in collection II. On a local

level, the phrase presents two versions of 4-3 separated by minor third, as marked on the

example. On a slightly larger scale, it projects another tetrachord, formed by its two prominent

perfect fourths. Like the neighbour chord concluding the previous phrase, this latter tetrachord

partitions 4-26 into two ic5 dyads related by ic3, thus expressing 5 * 3 in the terminology of

transpositional combination. On the other hand, the 4-3s of the phrase unite two ic1 dyads related

20

by ic3, or 1 * 3 from the standpoint of transpositional combination. Hence the two tetrachords

relate via ic1/ic5 interval exchange, as illustrated in Ex. 35.

This interval-exchange relationship between 4-3 and 4-26 continues to unfold over the

rest of the song. For another small-scale instance, Ex. 36 shows an excerpt from a few bars later,

closely related to phrase 2 of the introduction. This new passage is dominated by the second 4-3

of the earlier phrase (shown with brackets), along with the same 4-26, this time stated more

explicitly as the cadence harmony of the phrase (enclosed in the box). Once again, the two

tetrachords are connected by interval exchange. Ex. 37 interprets the relationship in dual interval

space, enclosing the 4-3 with two dotted horizontal boxes and the 4-26 with two vertical boxes.

As the example shows, the tetrachords can be related so that their shared notes D and F remain

invariant under the flipping operation; these common notes, moreover, function as local tonic

and supporting upper third.

The connection between these two tetrachord types assumes a broader, even extramusical

significance on considering the vocal part. During the song, the voice repeatedly intones the

gesture of a falling minor third, filled in with a passing note; these minor thirds often appear in

pairs, with the second one a perfect fifth higher than the first. As a result, the vocal part

repeatedly projects various transpositions of 4-26, again expressed as 5 * 3. Ex. 38 gives several

examples, which together account for a large fraction of the vocal part. As it happens, all of these

phrases are variations of a melody that Shostakovich quoted from a trio by Galina Ustvolskaya, a

former student and object of (ultimately unrequited) affection. (Shostakovich proposed to her

after the death of his first wife, but she turned him down.)

28

Within the context of the song,

therefore, set-class 4-26 becomes linked to Ustvolskaya, in effect serving as her emblem.

21

By contrast, the songs frequent scalar presentations of set-class 4-3 (like those in Exs. 34

and 36) almost certainly symbolise Shostakovich himself. Some twenty years earlier, in his

Tenth Symphony (1953), Shostakovich introduced his musical motto, DECB. From that

piece onward, Shostakovich frequently (and at times obsessively) used that motto at various

transposition levels, both in its original ordering, and also with the pitches reordered (especially

as a scalar unit). Interval exchange in ic1/ic5 space thus supplies the essential link between the

tetrachordal emblems of the song.

Going a step further, this exchange relationship mirrors certain basic aspects of the songs

text. Quoted below in English translation, the poem comprises two quatrains. Of these, the first

was written by the Florentine poet Giovanni Strozzi in praise of Michelangelos Night, a figure

of a sleeping female sculpted for the Medici Tomb of San Lorenzo in Florence; the second is

Michelangelos reply.

The Night that you see sleeping in such a

graceful attitude, was sculpted by an Angel

in this stone, and since she sleeps, she must have life;

wake her, if you dont believe it, and shell speak to you.

Sleep is dear to me, and being of stone is dearer,

as long as injury and shame endure;

not to see or hear is a great boon to me;

therefore, do not wake mepray, speak softly.

29

22

Speaking through the persona of Night, Michelangelo advocates remaining aloof and

insulating oneself from society in difficult times. Surely this sentiment resonated with

Shostakovich, given the trials he faced working under the Soviet regime. But on a more specific

level, Shostakovichs music engages another facet of the text: its suggestion of dialogue. As a

statement and response, the poems two stanzas form the beginnings of a dialogue, a feature that

Shostakovichs titleNight-Dialogueexplicitly acknowledges. (The original text bore no

title.) Moreover, the text focuses on the subject of dialogue, specifically, a dialogue with the

figure of Night (wake her . . . and shell speak to you). In basing his vocal part on the

Ustvolskaya melody, Shostakovich invites us to compare her with Night, establishing a

parallelism with the text. This parallelism, in turn, suggests the possibility for dialogue with

her.

30

At the same time, of course, Shostakovich quite literally sets his music in dialogue with

hers, and thus fully instantiates that parallelism.

31

Taken in this context, then, the interplay

between the emblematic tetrachords (and, by extension, between ic1 and ic5) complements

various dialogues unfolding in both music and text.

Finally, this dialogue of tetrachords has a significant precedent in an earlier and more

well-known piece by Shostakovich: the third movement of the Tenth Symphony, in which his

motto makes its debut. During this movement, Shostakovich juxtaposes his newly-introduced

motto with a repeated horn call that we now know symbolises Elmira Nazirovalike

Ustvolskaya, a former student and love interest.

32

Ex. 39 shows an instance from near the end of

the movement. Here, the two most prominent notes of the Elmira motive, E and A, join with

the tonic and supporting fifth to form the cadential sonority for the movement, the added-sixth

chord {C, E, G, A}. The movements final chord is thus infused with the musical image of

23

Nazirova. Yet as with Ustvolskayas tetrachordal emblem, this final chord belongs to set-class 4-

26, and therefore stands in the same relation to Shostakovichs motto as does Ustvolskayas

emblem. As David Fanning has suggested, both Ustvolskaya and Nazirova played the role of

unattainable female muse for Shostakovich.

33

Thus we could hear set-class 4-26 as a symbol

for this muse, a sonic image of the female other related by ic1/ic5 exchange to Shostakovichs

personal signature.

* * *

After all of this discussion about ic1 and ic5 in Shostakovichs music, a few questions

still linger. For example, why Shostakovichs interest in these interval-classes? One possibility is

that of all interval-classes, ic1 and ic5 are the only ones that can generate cycles encompassing

all twelve pitch-classes (i.e. the chromatic scale and the circle of fifths). Therefore this interval-

class pairing offers a uniquely flexible way to navigate pitch-class space. In addition, ic1 and ic5

best embody the polarity between consonance and dissonance, or stability and instability.

Shostakovichs music often conveys this dichotomy by treating ic5 harmonically and ic1

melodically. For instance, in the excerpt from the Fifteenth Symphony shown in Ex. 7, the

accompaniment comprises two vertical ic5 dyads linked by ic1 motion; and in the opening of the

Twelfth String Quartet (Ex. 23, starting in bar 2), {D, A} provides the harmonic foundation

while {A, B} serves as the main melodic gesture.

34

Finally, for string players, semitones and

perfect fifths (or perfect fourths) represent the two kinds of adjacency on the fingerboard (i.e.

moving along a string or crossing from one to another); thus a string players territory is

24

measured in terms of ic1 and ic5. Shostakovich exploits this aspect of string instrument

topography in the excerpts from the Viola Sonata considered above (Ex. 6).

35

One might also wonder: did Shostakovichs handling of ic1 and ic5 change over time,

and if so, how? Certainly instances of ic1/ic5 interaction become more frequent in

Shostakovichs later music (and indeed half of the above examples date from the last seven years

of his life). In addition, later instances are often more focused and direct. Compare for example

the opening eight bars of the Funeral March (Exs. 20 and 22) with the excerpt from the

Fourteenth Symphony quoted in Ex. 3. In both passages the music conveys a series of three

semitone-related ic5 dyads, which combine to form a version of hexachord 6-z6[012567]. In the

earlier piece this hexachord serves as the underlying framework for a passage that incorporates

several additional pitch classes. In the later piece, by contrast, the hexachord stands alone,

distilled and unadorned.

36

This difference notwithstanding, the two passages are linked by a

similar approach to intervallic structure, an approach rooted in the interplay of ic1 and ic5.

Ic1/ic5 interaction thus forms a thread of continuity running through his entire career, in

accordance with David Fannings observation that the composers final years brought no

fundamental evolution in Shostakovichs style.

37

25

NOTES

1

Most writers use traditional interval labels, as in semitone, perfect fourth, etc. See Hans

Keller, Shostakovichs Twelfth Quartet, Tempo 94 (1970), p. 12; Laurel Fay, Musorgsky and

Shostakovich, in Malcolm Hamrick Brown (ed.), Musorgsky, in Memoriam, 18811981 (Ann

Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1982), p. 222; Richard M. Longman, Expression and Structure:

Processes of Integration in the Large-Scale Instrumental Music of Dmitri Shostakovich (New

York: Garland, 1989), p. 382; and Eric Roseberry, Ideology, Style, Content, and Thematic

Process in the Symphonies, Cello Concertos, and String Quartets of Shostakovich (New York:

Garland, 1989), pp. 33135 and 33743. Elsewhere Fay has observed that minor seconds and

perfect fourths often occur together in late Shostakovich; see The Last Quartets of Dmitrii

Shostakovich: a Stylistic Investigation (PhD diss., Cornell University, 1978). Although

providing several examples, she does not pursue the matter in detail.

2

Ic1 and ic5 continue to dominate for another twenty measures of the piece. Also, some readers

may notice that Shostakovich presented a variation of this passage over thirty years later in the

third (cadenza) movement of his First Cello Concerto (1959). Some may balk at the mixture of

tonal and post-tonal terminology that I use here (e.g. perfect fourth and ic5 in the same

sentence). Nonetheless, it seems both natural and appropriate, since Shostakovichs music

routinely combines both kinds of materials.

3

Probing further, one could argue that the subtle appeal of these measures stems from the twofold

way that the second half of the vibraphone solo balances the first. Not only do the vertical dyads

of the second half retrograde those of the first, but if actual interval sizes are taken into account,

26

the second half presents a complementary opposite pattern in which the vertical fourths of the

first half change to fifths (and vice versa); in other words, the pattern fourth, fourth, fifth,

fourth in the first half leads to fifth, fifth, fourth, fifth in the second.

4

See Stephen C. Brown, Dual Interval Space in Twentieth-Century Music, Music Theory

Spectrum 25/i (2003), pp. 3557.

5

By convention, the lower interval-class number is given first.

6

Interval exchange in ic1/ic5 space has the same effect on pitch classes as T

x

M

5

or T

x

M

7

, where

x depends on the placement of the axis within the space. However, partial inversion does not (in

general) have the same effect as any traditional pitch-class operation. Moreover, interval

exchange in the other spaces does not affect pitch-classes in any traditional way. For more on the

effects of the flipping operations, see Brown, pp. 4852.

7

To cite a well-known example, the second movement of the Tenth Symphony opens with a i

6

.

8

One could argue that the right- and left-hand parts do relate via ic1/ic5, since G, the low note of

the right hands first stacked-fourth trichord, relates by ic1 to the A of the left hand. Yet the

reading offered here better accords with the partly tonal (and partly triadic) nature of

Shostakovichs musical language.

9

On a more abstract level, the diatonic collection could be understood as generated by ic5, and

thus reconciled to the sphere of ic1/ic5 interaction. This issue will be taken up below in the

context of Russian modal theory and its relation to ic1/ic5 structure.

10

Then again, the central role of ic1 in the twelve-note melody does relate it at least tangentially

to the ic1/ic5 activity of the viola part. That is, the piano line is primarily driven by chromatic

27

(i.e. ic1-based) descending motion (combined with chromatic gap-filling), and is framed by the

ic1 span DD! (spelled downward). Moreover, the initial DC of the twelve-note melody

provides an ic1 motivic link to the viola part.

11

Peter Child, Voice-Leading Patterns and Interval Collections in Late Shostakovich: Symphony

No. 15, Music Analysis 12/i (1993), pp. 7188.

12

Alternatively, the second subphrase could be heard as a string of three ic1 dyads filling in the

perfect fourth: AG, FG, FE. Either way, ic1 and ic5 clearly function as the primary interval

classes.

13

Ellon Carpenter, Russian Theorists on Modality in Shostakovichs Music, in David Fanning

(ed.), Shostakovich Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 90.

14

Ibid.

15

These terms were coined by Alexander Dolzhansky and Lev Mazel, respectively. See

Alexander Dolzhansky, O ladovoy osnove sochineniy Shostakovicha [On the modal basis of

Shostakovichs compositions], in Chert stilya Shostakovicha [Traits of Shostakovichs style]

(Moscow: Sovetskiy Kompozitor, 1962), p. 27; article originally appeared in Sovetskaya Muzka

4/1947, pp. 6574. Lev Mazel, Nablyudeniya nad muzkalnm yazkom D. Shostakovicha

[Observations on the musical language of D. Shostakovich], in Etyud o Shostakoviche [Studies

on Shostakovich] (Moscow: Sovetskiy Kompozitor, 1986), p. 48; article originally appeared as

Zametki o muzkalnom yazke Shostakovicha [Notes on the musical language of

Shostakovich], in G. Ordzhonikidze (comp.), Dmitry Shostakovich (Moscow: Sovetskiy

Kompozitor, 1967).

28

16

V. Sereda, O ladovoy strukture muzki Shostakovicha [On the modal structure of the music of

Shostakovich], in S. Skrebkov (ed.) Vopros teorii muzki [Questions of the theory of music]

(Moscow: Muzka, 1968), pp. 33338. Several other Russian theorists have also discussed the

theme (but again, just the first part). Eleonora Fedosova divides the melody into the same two

diminished-fourth spans. See Diatonicheskiye lad v tvorchestve D. Shostakovicha [Diatonic

modes in the works of D. Shostakovich] (Moscow: Sovetskiy Kompozitor, 1980), pp. 11112.

Dolzhansky and Mazel cite the melody as an instance of double-lowered Aeolian

(Dolzhansky) or doubly-intensified Aeolian (Mazel); that is, Aeolian with lowered ^4 and ^8.

See Dolzhansky, p. 28, and Mazel, p. 40.

17

See Ellon Carpenter, Contributions of Taneev, Catoire, Conus, Garbuzov, Mazel, Tiulin, in

Gordon D. McQuere (ed.), Russian Theoretical Thought in Music (Ann Arbor: UMI Research

Press, 1983), pp. 35254.

18

E. Fedosova, Diatonicheskiye lad v tvorchestve Shostakovicha [Diatonic modes in the work of

Shostakovich], (Moscow: Sovetskiy Kompozitor, 1980), pp. 13132.

19

In other words, the initial cell is multiplied or transpositionally combined with itself. For more

on transpositional combination, see Richard Cohn, Inversional Symmetry and Transpositional

Combination in Bartk, Music Theory Spectrum 10 (1988): pp. 1942.

20

There are some minor exceptions to the overall leftward trend of the music. For instance, in

part 3, the {D, A} dyad enters after {C, G} (even though it is located to the right of it in the

diagram); then again, the last statement of {C, G} comes after {D, A}.

29

21

In this connection, the reader may recall our very first example, taken from the First Piano

Sonata, which also features an ic1/ic5 structure operating in conjunction with the C major

diatonic collection.

22

In retrospect, we can hear the {A, E} at the end of Part 2 as V of this Neapolitan harmony,

though its resolution is obscured by the entrance of the C major harmony, which comes between

the two chords.

23

A significant difference is that in bars 2425, the square tetrachord is expressed as two ic1

dyads related by ic5, whereas in Part 3, it emerges as two ic5 dyads related by ic1. In essence,

this is an instance of set-class-preserving interval exchange, or what Richard Cohn in his work

on transpositional combination would call dimension exchange; see Cohn, pp. 3132.

24

Kellers language is slightly ambiguous, in that he refers to the fourth and the minor second,

both straight and in octave transposition. However, it is fairly clear from the context that he

means the perfect fourth, the minor second, and their complements; see Keller, p. 12.

25

The row is one of several sprinkled throughout the movement, typically played by solo

instruments at formal junctures. Though often similar in motivic design, they are mostly

unrelated by standard serial operations.

26

As defined by Pieter van den Toorn, octatonic collection I is the one that can be spelled in

scalar order beginning with pitch-classes 1 and 2; collection II begins with 2, 3, . . . and

collection III with 3, 4, . . .. See The Music of Igor Stravinsky (New Haven: Yale University

Press, 1983), pp. 48ff.

30

27

By placing G in the lowest register and doubling it in several octaves, Shostakovich obscures

Cs role as tonic. At the end of the song, however, Shostakovich rectifies the opening harmony

by placing C in the lowest register, clarifying its tonic function.

28

Fay, Shostakovich: a Life, p. 383. Shostakovich earlier quoted the Ustvolskaya melody in the

first movement of his Fifth String Quartet, as discussed by David Fanning, Shostakovich and

His Pupils, in Laurel Fay (ed.), Shostakovich and His World (Princeton: Princeton University

Press, 2004), pp. 28590. For more on Shostakovich and Ustvolskaya, see Louis Blois,

Shostakovich and the Ustvolskaya Connexion: a Textual Investigation, Tempo 182 (1992), pp.

1018.

29

As translated in James M. Saslow, The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Annotated Translation

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), p. 419.

30

Blois, pp. 1718, briefly touches on this issue of dialogue.

31

Indeed, one might say that Shostakovichs music, with its frequent alternations between his

material and Ustvolskayas, consummates a dialogue that goes unrealized in the poem (since it is

only a statement and response)a dialogue, moreover, that Michelangelos response warns

against, and that Ustvolskaya herself thwarted.

32

Nelly Kravetz, A New Insight into the Tenth Symphony of Dmitry Shostakovich, in

Rosamund Bartlett (ed.), Shostakovich in Context (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp.

15974.

33

David Fanning, Shostakovich and His Pupils, in Laurel Fay (ed.), Shostakovich and His

World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), pp. 28591.

31

34

Certainly there are exceptions to these interval-roles. Melodies built from chains of perfect

fourths are especially common in late Shostakovich; a good example occurs in the beginning of

the second song from the Six Verses of Marina Tsvetayeva, Op. 140. And though it is less

common for Shostakovich to treat ic1 vertically, there are still some examples. For instance, the

Thirteenth String Quartet (at R17) features chords built out of stacked minor ninths.

35

Certainly Shostakovich was not alone in his predilection for ic1/ic5 pairings: Bartk,

Stravinsky, and Webern (among others) all wrote passages highlighting ic1 and ic5. For some

examples, see Bartk: Mikrokosmos no. 110 (Clashing Sounds), String Quartet No. 4, ii, and

Concerto for Orchestra, iii; Stravinsky: Three Pieces for String Quartet, ii; and Webern, Five

Pieces for String Quartet, Op. 5, iv.

36

For similar deployments of this hexachord in between these works, see the Eighth Symphony,

iv, R118, bars 35 (piccolo part), and the Eleventh String Quartet, iii, last three bars.

37

David Fanning, Shostakovich, Dmitry (Dmitriyevich), in Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell

(eds.), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London: Macmillan, 2001), vol. 23,

p. 299.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Ligeti - Concierto de Cámara para 13 Instrumentos - 4to Mov CON ANOTACIONESDokument20 SeitenLigeti - Concierto de Cámara para 13 Instrumentos - 4to Mov CON ANOTACIONESpinorosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instrument Reference Chart v4Dokument2 SeitenInstrument Reference Chart v4Rosie Chase100% (6)

- Time and Texture in Lutoslawski's Concerto For Orchestra and Ligeti's Chamber Concerto'Dokument37 SeitenTime and Texture in Lutoslawski's Concerto For Orchestra and Ligeti's Chamber Concerto'andrewcosta100% (2)

- MUSICAL CYCLES - Sounds and Gyorgy Ligeti FINAL PDFDokument21 SeitenMUSICAL CYCLES - Sounds and Gyorgy Ligeti FINAL PDFrodrigojuli100% (1)

- Searby M 6293Dokument8 SeitenSearby M 6293pinorosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gruppen Instruments EnglishDokument3 SeitenGruppen Instruments EnglishpinorosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Naming A ChordDokument1 SeiteNaming A ChordpinorosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dvorak - Symphony No. 9 Op.95 4-HandsDokument72 SeitenDvorak - Symphony No. 9 Op.95 4-HandssergotenksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proteus LibraryDokument67 SeitenProteus LibraryNeisarg DaveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hola ChicoDokument1 SeiteHola ChicopinorosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Armonicos ViolinDokument3 SeitenArmonicos ViolinpinorosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Pitch and Texture Analysis of Ligeti S Lux Aeterna Jan Jarvlepp PDFDokument8 SeitenPitch and Texture Analysis of Ligeti S Lux Aeterna Jan Jarvlepp PDFOsckarello100% (1)

- SonatinaDokument1 SeiteSonatinaRobby FerdianNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Guitar Picking Exercises To Develop Technique - Jamie Holroyd Guitar - Jamie Holroyd GuitarDokument4 Seiten2 Guitar Picking Exercises To Develop Technique - Jamie Holroyd Guitar - Jamie Holroyd GuitarWayne White50% (2)

- EK Sample Sight Reading 6-8 PDFDokument6 SeitenEK Sample Sight Reading 6-8 PDFTech talentsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Melodic OutlinesDokument40 SeitenMelodic OutlineslopezdroguettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vocal PedagogyDokument20 SeitenVocal PedagogyDhei TulinaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jazz HarmonyDokument11 SeitenJazz HarmonypabloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dulcimer Movable ChordsDokument4 SeitenDulcimer Movable ChordsElecktra Blue100% (1)

- PatMethenyBlues DissertDokument60 SeitenPatMethenyBlues DissertAlexandre Antunes100% (3)

- Treble and Bass Clef Beg Intro and PracticeDokument4 SeitenTreble and Bass Clef Beg Intro and PracticeTyrone CaberoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 7 - Chord Substitutions (Eb)Dokument5 SeitenLesson 7 - Chord Substitutions (Eb)戴嘉豪Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reharmonisation (Maj7, m7, V7) - Sheet1 PDFDokument5 SeitenReharmonisation (Maj7, m7, V7) - Sheet1 PDFowenNoch keine Bewertungen

- MS MelodicRockSoloing101Dokument54 SeitenMS MelodicRockSoloing101Eifla GonzalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ii V I Progression: IiviincmajorDokument9 SeitenIi V I Progression: IiviincmajorKatie BirtNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Modality To TonalityDokument46 SeitenFrom Modality To TonalityNuti Dumitriu100% (2)

- SALT - Marcin Patrzalek (Guitar Tab)Dokument9 SeitenSALT - Marcin Patrzalek (Guitar Tab)Dawid Wojewoda100% (2)

- AP Music Theory: Free-Response QuestionsDokument9 SeitenAP Music Theory: Free-Response QuestionsSheryll ButhapatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 5 RevisionDokument3 SeitenGrade 5 RevisionAlla Pashkova0% (1)

- Flute: Grade 5 Scales & ArpeggiosDokument3 SeitenFlute: Grade 5 Scales & ArpeggiosJoyce KwokNoch keine Bewertungen

- GCE Music Sample Assessment Materials For Teaching From 2016 WALES PDFDokument141 SeitenGCE Music Sample Assessment Materials For Teaching From 2016 WALES PDFNettieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beethoven Cello Sonata Opus 69 AnalysisDokument33 SeitenBeethoven Cello Sonata Opus 69 Analysisonna_k154122100% (1)

- Live and Let Die - Arrangement SATBDokument6 SeitenLive and Let Die - Arrangement SATBmissloly3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dave Brubeck and Polytonal JazzDokument25 SeitenDave Brubeck and Polytonal JazzKeyvan Unhallowed MonamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marry Me by TrainDokument3 SeitenMarry Me by TrainWolfgang EmbacherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dirty Deeds Done Dirt CheapDokument7 SeitenDirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheapandreas papandreouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alban Berg Op.4 (René Lebow.)Dokument27 SeitenAlban Berg Op.4 (René Lebow.)Sergi Puig SernaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bartollo - Aria - La VendettaDokument4 SeitenBartollo - Aria - La VendettaJack PhillipsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guitar Rock LicksDokument4 SeitenGuitar Rock LicksAlekanian AlainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Species Counterpoint SummaryDokument4 SeitenSpecies Counterpoint SummaryBNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Staff, Treble Clef and Bass Clef: TablatureDokument39 SeitenThe Staff, Treble Clef and Bass Clef: TablatureNguyễn LinhNoch keine Bewertungen