Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

ARA Rivadavia Argentine Battleship

Hochgeladen von

Mohamed FayadOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ARA Rivadavia Argentine Battleship

Hochgeladen von

Mohamed FayadCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

For the survey ship, see ARA Comodoro Rivadavia (Q-11).

ARA Rivadavia

Career Argentine Navy

Name: Rivadavia

Namesake: Bernardino Rivadavia

Builder: Fore River Shipbuilding

Company

Laid down: 25 May 1910

Launched: 26 August 1911

Commissioned: 27 August 1914

Decommissioned: 1952

Fate: Sold to Italy for scrapping in

1957, scrapped later

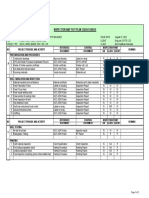

General characteristics

Type: Rivadavia-class battleship

Displacement:

27,500 long tons

(27,900 t)standard,

30,100 long tons (30,600 t) full

load

[1]

Length:

594 ft 9 in (181.28 m) oa,

585 ft (178 m) pp

[1]

Beam: 98 ft 4.5 in (29.985 m)

[1]

Draft: 27 ft 8.5 in (8.446 m)

[1]

Propulsion:

3-shaft, Curtis geared turbines,

18 Babcock & Wilcox boilers;

40,000 shp (29,828 kW)

[1]

Speed: 22.5 knots (25.9 mph;

41.7 km/h)

[1]

Range:

7,000 nautical miles (8,100 mi;

13,000 km) at 15 knots

(17 mph; 28 km/h)

[1]

11,000 nautical miles

(13,000 mi; 20,000 km) at 11

knots (13 mph; 20 km/h)

[1]

Armament:

12 12-inch (305 mm) guns

[1]

12 6-inch (152 mm) guns

[1]

16 4-inch (102 mm) guns

[1]

2 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo

tubes

[1]

Armor:

Belt: 1210 inches (300

250 mm)

[1]

Turrets: 12 inches (305 mm)

[1]

Casemates: 9

1/3

6

1/5

inches

(238159 mm)

[1]

Conning tower: 12 inches

(300 mm)

[1]

ARA Rivadavia

[A]

was an Argentine battleship built during the South American dreadnought race.

Named after the first Argentine president, Bernardino Rivadavia,

[2]

it was the lead ship of its

class. Moreno was Rivadavia's only sister ship.

In 1907, the Brazilian government placed an order for two of the powerful new "dreadnought"

warships as part of a larger naval construction program. Argentina quickly responded, as the

Brazilian ships outclassed anything in the Argentine fleet. After an extended bidding process,

contracts to design and build Rivadavia and Moreno were given to the American Fore River

Shipbuilding Company. During their construction, there were rumors that the ships might be sold to a

country engaged in the First World War, but both were commissioned into the Argentine

Navy. Rivadavia underwent extensive refits in the United States in 1924 and 1925. The ship saw no

active service during the Second World War, and its last cruise was made in 1946.Stricken from the

naval register in 1957, Rivadavia was sold later that year and broken up for scrap starting in 1959.

Contents

[hide]

1 Background

2 Construction and trials

3 Attempted sale

4 Service

5 Footnotes

6 Endnotes

7 References

8 External links

Background[edit]

Main article: South American dreadnought race

Rivadavia's genesis can be traced to the naval arms races between Chile and Argentina which were

spawned by territorial disputes over their mutual borders in Patagonia and Puna de Atacama, along

with control of the Beagle Channel. These arms races flared up in the 1890s and again in 1902; the

latter was eventually stopped through British mediation. Provisions in the dispute-ending treaty

imposed restrictions on both countries' navies. The United Kingdom's Royal Navy bought the

twoConstitucin-class pre-dreadnought battleships that were being built for Chile, and Argentina sold

its two Rivadavia-classarmored cruisers under construction in Italy to Japan.

[3][4]

After HMS Dreadnought was commissioned by the United Kingdom, Brazil decided in early 1907 to

halt the construction of three obsolescent pre-dreadnoughts and begin work on

two dreadnoughts (the Minas Geraes class).

[5]

These ships, which were designed to carry the

heaviest battleship armament in the world at the time,

[6]

came as a shock to the navies of South

America,

[5]

and Argentina and Chile quickly canceled the 1902 armament-limiting pact.

[7]

Argentina in

particular was alarmed at the possible power of the ships. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Manuel

Augusto Montes de Oca, remarked that even oneMinas Geraes-class ship could destroy the entire

Argentine and Chilean fleets.

[8]

While this may have been hyperbole, either one was much more

powerful than any single vessel in the Argentinian fleet.

[9]

Debates raged in Argentina over whether

to spend more than two million pounds sterling to acquire dreadnoughts. With further border

disputes, particularly with Brazil near the Ro de la Plata (River Plate), Argentina made plans to

contract for their own dreadnoughts. After an extended bidding process, Rivadavia and Moreno were

ordered from the Fore River Shipbuilding Company in the United States.

[1][10]

Construction and trials[edit]

Laid down on 25 May 1910, Rivadavia was launched and christened on 26 August 1911 by Isabel,

the wife of the Argentine Minister to the United States Rmulo Sebastin Nan. Thousands of

people were present to witness the event,

[1][11]

including representatives from the Argentine Navy

and the country's legation in Washington. The United States sent the assistant chief of the Latin

American Division in the State Department, Henry L. James, to be its official representative. Two

United States Navy bureau chiefs also attended.

[11]

In mid-September 1913, Rivadavia conducted trials off Rockland, Maine, after a two-week delay due

to turbine malfunctions. During speed trials on the 16th,

[12]

the dreadnought was able to obtain a

maximum speed of 22.567 knots (25.970 mph; 41.794 km/h).

[13]

On a 30-hour endurance trial

starting the next day, Rivadavia damaged one of her turbines and had to put in at President Roads,

one of Boston Harbor's deep-water anchorages.

[12]

The turbines were still a problem as late as

August 1914. One was dropped by a crane in July and had to be removed for repairs in August.

[14]

Attempted sale[edit]

Over the course of their construction, Rivadavia and Moreno had been the subject of rumors that

Argentina would accept the ships and then sell them to Japan, a fast-growing military rival to the

United States, or to a European country.

[15]

The rumors were partially true; some in the government

were looking to get rid of the battleships and devote the proceeds to opening more

schools,

[16]

and The New York Times reported in late 1913 that the country had received several

offers from interested parties.

[13]

This angered the American government, which did not want its

warship technology offered to the highest bidder. Neither did they want to exercise a contract-

specified option that gave the United States first choice if the Argentines decided to sell, as naval

technology had already progressed past the Rivadavia class, particularly in the adoption of the "all-

or-nothing" armor scheme. Instead, the United States and its State Department and Navy

Department put diplomatic pressure on the Argentine government.

[17]

After socialist gains in the legislature, the Argentine government introduced several bills in May 1914

which would have put the battleships up for sale, but the bills were all defeated by late June.

Following the commencement of the First World War, the German and British ambassadors to the

United States both complained to the US State Department; the former believed that the British were

going to be given the ships as soon as the ships reached Argentina, and the latter considered it the

responsibility of the United States to ensure that the ships never left Argentina's possession.

International armament companies attempted to get Argentina to sell to one of the

smaller Balkancountries and expected that the ships would then find their way into the war.

[18][B]

Service[edit]

Rivadavia was commissioned into the Armada de la Repblica Argentina on 27 August 1914 at

the Charlestown Navy Yard,

[19][20]

although it was not fully completed until December.

[1]

On 23

December 1914, Rivadavia left the United States for Argentina. It arrived in its capital, Buenos Aires,

on 19 February 1915. Over 47,000 people came out to see the new ship over the next three days,

including the President Victorino de la Plaza. In April 1915, Rivadavia was put into the training

division of the Navy, remaining there until 1917, when the navy transferred the ship into the First

Division. In 1917, Rivadavia sailed to Comodoro Rivadavia when communist oil workers went on

strike.

[19]

Later in 1917, the Argentines had to sharply curtail Rivadavia's activities because of a fuel shortage,

but they voyaged to the United States with the Argentine ambassador in 1918.

[19]

Rivadavia then

took on a load of gold bullion and brought it back to Argentina, docking in Puerto Belgrano on 23

September 1918.

[19][21]

In December 1920, Rivadaviaparticipated in ceremonies that marked the

400th anniversary of the discovery of the Strait of Magellan. On the 2nd, the ship called

on Valparaso in Chile; 25 days later, it took part in an international naval review. Two years

later, Rivadavia was placed into reserve.

[19]

In 1923, the Navy decided to send Rivadavia to the United States to be modernized. The ship

departed on 6 August 1924 and reached Boston on the 30th, where it spent the next two

years. Rivadavia was converted to use fuel oil instead of coal and had "a general machinery

overhaul".

[22]

A new fire-control system was fitted with rangefinders on the fore and aft superfiring

turrets, and the aft mast was replaced by a tripod. A funnel cap was installed so that smoke from the

funnels did not interfere with accurate rangefinding of enemy ships. The 6-inch secondary armament

was retained, but the smaller 4-inch guns were taken off in favor of four 3-inch (76 mm) anti-

aircraft guns and four 3-pounders.

[23][24]

After sailing back to Argentina in March and April 1926,

[25]

Rivadavia spent the remainder of the year

undergoing sea trials. The dreadnought joined the training division once again in 1927, but

after Rivadavia made four training cruises, the division was disbanded, and the ship remained

moored in Puerto Belgrano until 1929. This began a series of cyclic activity followed by being

demoted to the reserve fleet. Although active in both 1929 and 1930, Rivadavia was placed in

reserve on 19 December 1930. Shortly thereafter, it was restored to active service to serve as

the flagship for 1931 fleet exercises. Rivadavia went back into reserve in 1932 before coming back

out in January 1933. It remained in full commission for most of the rest of the decade as part of the

Battleship Division, alongside Moreno.

[19]

Rivadavia on her speed trials

In January 1937, the ship called on Valparaso and Callao in Peru. In company

with Moreno, Rivadavia left Puerto Belgrano for Europe on 6 April. After crossing the ocean, they

split up, with Rivadavia mooring at the French port of Brest while Moreno took part in the

BritishCoronation Review in Spithead. The two ships then journeyed to several German ports: both

put in at Wilhelmshaven before Rivadaviawent to Hamburg and Moreno to Bremen. They returned to

Argentina on 29 June.

[19]

While Rivadavia made an official visit to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1939, Argentina remained neutral

for the majority of the Second World War, and the aging dreadnought saw no active service.

[19]

Her

next cruise came after the war ended (29 October to 22 December 1946), when she called on

countries in the Caribbean and northern South America, including Trinidad, Venezuela, and

Colombia. This was the last time the ship would be in service under her own power. Moored in

Puerto Belgrano from 1948 on, the ship was rendered inoperable in 1951 and cannibalized for many

years for useful arms and equipment. On 18 October 1956, the ship was listed for disposal, and she

wasstricken from the Navy on 1 February 1957. On 30 May, Rivadavia was sold to an Italian ship

breaking company for US$2,280,000. Beginning on 3 April 1959, the ship was towed by

two tugboats to Savona, Italy, where they arrived on 23 May. She was thereafter broken up

in Genoa.

[19]

Footnotes[edit]

1. Jump up^ "ARA" is an acronym for Armada de la Repblica Argentina.

2. Jump up^ The specific example given in Livermore, footnote 106, is that a "group of French

bankers, on behalf of the Russian government, were offering in gold twice the contract price of

the ships, which were to be turned over to Greece."

[18]

Turning over the ships was likely meant as

a way around the United States' neutrality rules.

Endnotes[edit]

1. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

j

k

l

m

n

o

p

q

r

s

Scheina, "Argentina," 401.

2. Jump up^ Whitley, Battleships, 19.

3. Jump up^ Scheina, Naval History, 4552.

4. Jump up^ Garrett, "Beagle Channel Dispute," 8688.

5. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Whitley, Battleships, 24.

6. Jump up^ "Germany may buy English warships," The New York Times, 1 August 1908, C8.

7. Jump up^ Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 32.

8. Jump up^ Martins Filho, "Colossos do mares," 76.

9. Jump up^ Scheina, "Argentina," 400.

10. Jump up^ Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 33.

11. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

"Launch Rivadavia, Biggest Battleship," The New York Times, 27 August 1911,

7.

12. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

"Accident to Rivadavia," The New York Times, 19 September 1913, 1.

13. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

"Argentine Warship Makes 22.56 Knots," The New York Times, 17 September

1917, 2.

14. Jump up^ "The Rivadavia Delayed," The New York Times, 24 August 1914, 7.

15. Jump up^ "Germany Will Buy Two Battleships," Toronto World, 10 August 1914, 12.

16. Jump up^ Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 45.

17. Jump up^ Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 4546.

18. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 4647.

19. ^ Jump up to:

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

Whitley, Battleships, 21.

20. Jump up^ "Argentina's Ship Ready," The New York Times, 28 August 1914, 7.

21. Jump up^ "Orders the Rivadavia to Bring Gold," The New York Times, 7 October 1918, 12.

22. Jump up^ Scheina, "Argentina," 402.

23. Jump up^ Whitley, Battleships, 2122.

24. Jump up^ Burzaco and Ortz, Acorazados y Cruceros, 94.

25. Jump up^ "Rivadavia Off For Home," The New York Times, 15 March 1926, 12.

References[edit]

Battleships portal

Burzaco, Ricardo and Patricio Ortz. Acorazados y Cruceros de la Armada Argentina, 18811992. Buenos

Aires: Eugenio B. Ediciones, 1997. ISBN 987-96764-0-8.OCLC 39297360.

Martins, Joo Roberto, Filho. "Colossos do mares [Colossuses of the Seas]." Revista de Histria da

Biblioteca Nacional 3, no. 27 (2007): 7477. ISSN 1808-4001. OCLC 61697383.

Garrett, James L. "The Beagle Channel Dispute: Confrontation and Negotiation in the Southern

Cone." Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 27, no. 3 (1985):, 81

109.JSTOR 165601. ISSN 0022-1937. OCLC 2239844.

Livermore, Seward W. "Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 19051925." The Journal of Modern

History 16, no. 1 (1944):, 3144. JSTOR 1870986. ISSN 0022-2801. OCLC 62219150.

Scheina, Robert L. "Argentina" in Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 19061921, edited by Robert

Gardiner and Randal Gray, 400402. Annapolis, Maryland, United States: Naval Institute Press,

1984. ISBN 0-87021-907-3. OCLC 12119866.

. Latin America: A Naval History 18101987. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987. ISBN 0-87021-

295-8. OCLC 15696006.

Whitley, M.J. Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Annapolis, Maryland, United

States: Naval Institute Press, 1998. ISBN 1-55750-184-X. OCLC 40834665.

External links[edit]

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Wikipedia's Featured Article - 2015-09-10 - Minas Geraes-Class BattleshipDokument11 SeitenWikipedia's Featured Article - 2015-09-10 - Minas Geraes-Class BattleshipFernando Luis B. M.Noch keine Bewertungen

- LCVP DesignDokument8 SeitenLCVP DesignFrank CastleNoch keine Bewertungen

- WWII Liberty Ships HistoryDokument30 SeitenWWII Liberty Ships HistoryCAP History Library100% (1)

- Minas Geraes-Class BattleshipDokument11 SeitenMinas Geraes-Class BattleshipCyrus Yu Shing ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ShiptechDokument14 SeitenShiptechAzeem ZulkarnainNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Prince Ships 1940-45. Royal Canadian Navy Armed Merchant Cruiser OperationsDokument236 SeitenThe Prince Ships 1940-45. Royal Canadian Navy Armed Merchant Cruiser OperationsDana John NieldNoch keine Bewertungen

- US Navy Interwar Cruiser Design and DevelopmentDokument20 SeitenUS Navy Interwar Cruiser Design and DevelopmentJeffrey Edward York100% (4)

- Analisis TFC FinalDokument98 SeitenAnalisis TFC FinalMartín Dione100% (1)

- Dictionary of Disasters at Sea 1994 Hocking 1843423812Dokument778 SeitenDictionary of Disasters at Sea 1994 Hocking 1843423812Carlos Lucho Schumacher100% (2)

- US Navy Interwar Cruiser Design and DevelopmentDokument20 SeitenUS Navy Interwar Cruiser Design and Developmentmrcdexterward0% (1)

- USS Cyclops (AC-4)Dokument7 SeitenUSS Cyclops (AC-4)Haron Al-kahtaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blue RibandDokument20 SeitenBlue Ribandelenaanalia88Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Boat that Won the War: An Illustrated History of the Higgins LCVPVon EverandThe Boat that Won the War: An Illustrated History of the Higgins LCVPBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Japanese Navy Type A barge transport details during WWIIDokument8 SeitenJapanese Navy Type A barge transport details during WWIIskippygoat11100% (1)

- MalekDokument25 SeitenMalekJaber SufianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nws 1Dokument10 SeitenNws 1Jaber SufianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our Privacy Policy Is Changing On 24 May 2018Dokument137 SeitenOur Privacy Policy Is Changing On 24 May 2018elazarocNoch keine Bewertungen

- SubmarineDokument30 SeitenSubmarinerbnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- HMS Warrior (R31)Dokument5 SeitenHMS Warrior (R31)rbnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil War Navies 1855 1883 The Us Navy Warship SerDokument240 SeitenCivil War Navies 1855 1883 The Us Navy Warship SerFabrizio De Petrillo67% (3)

- Jeremiah O'Brien Liberty ShipDokument8 SeitenJeremiah O'Brien Liberty ShipCAP History Library100% (2)

- Standard-Type Battleship - TreatiseDokument3 SeitenStandard-Type Battleship - TreatiseJennifer AdvientoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hunting The German Shark; The American Navy In The Underseas War [Illustrated Edition]Von EverandHunting The German Shark; The American Navy In The Underseas War [Illustrated Edition]Bewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- Assault Landing Craft: Design, Construction & OperatorsVon EverandAssault Landing Craft: Design, Construction & OperatorsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Flying Catalinas: The Consoldiated PBY Catalina in WWIIVon EverandFlying Catalinas: The Consoldiated PBY Catalina in WWIIBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (5)

- United States Naval Aviation 1919-1941Dokument353 SeitenUnited States Naval Aviation 1919-1941Saniyaz Manas100% (14)

- Picket BoatDokument3 SeitenPicket BoatCyrus Yu Shing ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Triángulo De Las Bermudas. El Encubrimiento De La Guerra Del CaribeVon EverandEl Triángulo De Las Bermudas. El Encubrimiento De La Guerra Del CaribeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alaska-Class Cruiser - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokument11 SeitenAlaska-Class Cruiser - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediaadewa87100% (1)

- Search For The Graf SpeeDokument5 SeitenSearch For The Graf SpeeChristina Chavez Clinton0% (1)

- Metal To Counter Spanish FleetDokument10 SeitenMetal To Counter Spanish Fleettanelorn266Noch keine Bewertungen

- Enemy in Sight: The Royal Navy and Merchant Marine 1940-1942Von EverandEnemy in Sight: The Royal Navy and Merchant Marine 1940-1942Noch keine Bewertungen

- History of Curnard Line - M - Ari Deira - 24024118011Dokument3 SeitenHistory of Curnard Line - M - Ari Deira - 24024118011MUHAMMAD ARIDEIRA S.PNoch keine Bewertungen

- Henry J Kaiser The War YearsDokument5 SeitenHenry J Kaiser The War YearsJake GallardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hunter-Killer: U.S. Escort Carriers in the Battle of the AtlanticVon EverandHunter-Killer: U.S. Escort Carriers in the Battle of the AtlanticBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (5)

- SubmarineDokument28 SeitenSubmarinepriyanka12987Noch keine Bewertungen

- Japanese Battleships, 1897-1945: A Photographic ArchiveVon EverandJapanese Battleships, 1897-1945: A Photographic ArchiveBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- World War 2 In Review No. 68: British ‘Landing Craft Assault’Von EverandWorld War 2 In Review No. 68: British ‘Landing Craft Assault’Noch keine Bewertungen

- A WarshipDokument7 SeitenA WarshipParth DahujaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coast Guard Ship ConvoysDokument200 SeitenCoast Guard Ship ConvoysCAP History Library100% (3)

- LSR 3 PowerpointDokument129 SeitenLSR 3 Powerpointapi-76018903Noch keine Bewertungen

- A History of Canadian Naval Aviation 1918-1963Dokument169 SeitenA History of Canadian Naval Aviation 1918-1963djtj89100% (3)

- Canada's Role in the Battle of the AtlanticDokument3 SeitenCanada's Role in the Battle of the Atlanticnewgoblin5Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Third Voyage: A World War Ii Voyage of the Libertyship Albert Gallatio & CrewVon EverandThe Third Voyage: A World War Ii Voyage of the Libertyship Albert Gallatio & CrewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Praise and Insights for Memoirs of a U-boat CommanderDokument14 SeitenPraise and Insights for Memoirs of a U-boat Commandervtdamodaran50% (2)

- On Wave and Wing: The 100 Year Quest to Perfect the Aircraft CarrierVon EverandOn Wave and Wing: The 100 Year Quest to Perfect the Aircraft CarrierBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (4)

- IELTS Reading SkillDokument9 SeitenIELTS Reading SkillKaushik RayNoch keine Bewertungen

- NWC 1036, The 1982 Falklands Malvinas Case Study, 4 June 2010 PDFDokument84 SeitenNWC 1036, The 1982 Falklands Malvinas Case Study, 4 June 2010 PDFGonzalo GarecaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IntroductionDokument2 SeitenIntroductionpapabearNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cellular Network Planning and Optimization Part5Dokument47 SeitenCellular Network Planning and Optimization Part5Junbin FangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cellular Network Planning and Optimization Part5Dokument47 SeitenCellular Network Planning and Optimization Part5Junbin FangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secção de Sistemas de TelecomunicaçõesDokument21 SeitenSecção de Sistemas de TelecomunicaçõesControl A60100% (1)

- Secção de Sistemas de TelecomunicaçõesDokument21 SeitenSecção de Sistemas de TelecomunicaçõesControl A60100% (1)

- Cellular Network Planning and Optimization Part5Dokument47 SeitenCellular Network Planning and Optimization Part5Junbin FangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 of GSM RNP&RNO - GSM System Principles and Call FlowDokument99 SeitenChapter 2 of GSM RNP&RNO - GSM System Principles and Call FlowVivek TripathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ts - 123236v060000p MSC PoolDokument37 SeitenTs - 123236v060000p MSC PoolMohamed FayadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cellular Network Planning and Optimization Part5Dokument47 SeitenCellular Network Planning and Optimization Part5Junbin FangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ts - 123236v060000p MSC PoolDokument37 SeitenTs - 123236v060000p MSC PoolMohamed FayadNoch keine Bewertungen

- 930Dokument76 Seiten930Mohamed FayadNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3GPP TS 25.133Dokument142 Seiten3GPP TS 25.133Nickolai DydykinNoch keine Bewertungen

- ETSI TS 123 236: Technical SpecificationDokument39 SeitenETSI TS 123 236: Technical SpecificationMohamed FayadNoch keine Bewertungen

- GSM Cell Planning and Optimization Study Case: Sragen AreaDokument24 SeitenGSM Cell Planning and Optimization Study Case: Sragen AreadavidmiftahudinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stress and Thermal Analysis of An LNG Marine Loading ArmDokument2 SeitenStress and Thermal Analysis of An LNG Marine Loading ArmGoldy RattanNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Industrial Insurance Coverage? Industrial Insurance, Also Known As Workers' Compensation, Provides Medical and Non-Medical BenefitsDokument14 SeitenWhat Is Industrial Insurance Coverage? Industrial Insurance, Also Known As Workers' Compensation, Provides Medical and Non-Medical BenefitsJenny Marie B. AlapanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brain Book: Safe Skies, Capt. J. Tucker RojasDokument30 SeitenBrain Book: Safe Skies, Capt. J. Tucker RojasAriawan D RachmantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Senior Painting Coating & Insulation Inspector CVDokument4 SeitenSenior Painting Coating & Insulation Inspector CVHoàng Nguyên Võ100% (1)

- Cosmin Dandu - Short-Stories-The-Voyage-Of-The-Animal-Orchestra-Worksheet PDFDokument2 SeitenCosmin Dandu - Short-Stories-The-Voyage-Of-The-Animal-Orchestra-Worksheet PDFMihaela DanduNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Steel v. CA: Private vs Common CarrierDokument1 SeiteNational Steel v. CA: Private vs Common CarrierStephanie GriarNoch keine Bewertungen

- FN Nemtas 2. 20-30 NovDokument3 SeitenFN Nemtas 2. 20-30 NovCrystal PhillipsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inspection and Test Plan for Cargo Barge Hull FabricationDokument2 SeitenInspection and Test Plan for Cargo Barge Hull FabricationferdyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pirates of The Caribbean at Worlds End PDFDokument132 SeitenPirates of The Caribbean at Worlds End PDFAna Carolina Lopes VieiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- SHIP'S DETAILS FOR M/V DENSA COUGARDokument2 SeitenSHIP'S DETAILS FOR M/V DENSA COUGARBarış ÖzturkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atalanta Maritime Security Threat Update Red SeaDokument3 SeitenAtalanta Maritime Security Threat Update Red SeaROGER RUIZNoch keine Bewertungen

- BookDokument28 SeitenBookFebrian Wardoyo100% (1)

- Nomenclature For Single Hull TankerDokument28 SeitenNomenclature For Single Hull TankerRobin Gu100% (1)

- Shipping DictionaryDokument11 SeitenShipping DictionaryChamor GeremNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tom Ray and The Sinking of The SS SpaightDokument3 SeitenTom Ray and The Sinking of The SS SpaightAxinlandsurveys100% (2)

- Supreme Court Rules on Liability for Passenger Injuries from Firecracker Explosion in BusDokument31 SeitenSupreme Court Rules on Liability for Passenger Injuries from Firecracker Explosion in BusChieDelRosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Starfleet New OrleansDokument2 SeitenStarfleet New Orleansmimihell75Noch keine Bewertungen

- BSI ReportDokument1 SeiteBSI ReportEnriqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- DMir 1912 04-29-01-Investigando Bruce IsmayDokument20 SeitenDMir 1912 04-29-01-Investigando Bruce IsmayTitanicwareNoch keine Bewertungen

- How - To - Load - Max - The Art of Dredging PDFDokument10 SeitenHow - To - Load - Max - The Art of Dredging PDFSimon BurnayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of First Voyage Around The World of Magellan by Antonio Pigafetta AuthorDokument4 SeitenSummary of First Voyage Around The World of Magellan by Antonio Pigafetta AuthorJoy SolisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Singapore Anchorage, Fairway, Pilot Boarding, Pilot DisembarcationDokument5 SeitenSingapore Anchorage, Fairway, Pilot Boarding, Pilot DisembarcationButon SeamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jan Mathhew-ColeDokument1 SeiteJan Mathhew-ColeJan SzczepaniakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal Uas Semester Ganjil 2018.2019 - CKL TheoryDokument4 SeitenSoal Uas Semester Ganjil 2018.2019 - CKL TheoryRio Chandraa100% (1)

- Introduction To Submarine Design PDFDokument6 SeitenIntroduction To Submarine Design PDFradu tiberiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1050 Caribbean Way, Miami, Florida 33132-2096 1-877-414-CREW (2739) or 1-305-982-CREW (2739) FAX 305 / 603-0053Dokument3 Seiten1050 Caribbean Way, Miami, Florida 33132-2096 1-877-414-CREW (2739) or 1-305-982-CREW (2739) FAX 305 / 603-0053Bertrand DsouzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Code of Safe Working Practices: Objectives & ContentsDokument8 SeitenCode of Safe Working Practices: Objectives & Contentssidadams2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Air Independent PropulsionDokument19 SeitenAir Independent PropulsionRevanth NikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- TABACALERA INSURANCE CO v. NORTH FRONT SHIPPINGDokument2 SeitenTABACALERA INSURANCE CO v. NORTH FRONT SHIPPINGAlphaZuluNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISPS Audit FormDokument3 SeitenISPS Audit FormKunal SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

![Hunting The German Shark; The American Navy In The Underseas War [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259891153/149x198/d1f33f3f94/1617227774?v=1)