Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Strategy + Business

Hochgeladen von

Silvia PalascaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Strategy + Business

Hochgeladen von

Silvia PalascaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

y

+

b

u

s

i

n

e

s

s

A

u

t

u

m

n

2

0

1

1

64

C.K. PRAHALAD

THE GLOBAL MIDDLE CLASS

SYLVI A NASAR

www.strategy-business.com

M

A

N

U

F

A

C

T

U

R

I

N

G

S

W

A

K

E

-

U

P

C

A

L

L

Issue 64, Autumn 2011

US $12.95 Canada C$12.95

strategy+business

Published by Booz & Company

MANUFACTURING S

WAKE

-

UP CALL

THE CHALLENGE FOR U. S. COMPETI TI VENESS

THE RI SE OF DI GI TAL FABRI CATI ON

YOU CAN APPLY

EVERYTHING BACK

TO YOUR COMPANY.

THESE ARE LESSONS

YOU WILL ALWAYS

REMEMBER.

I CAME TO EXPLORE

WHAT DRIVES

THE BUSINESS

OF MEDICINE.

BUT I LEFT WITH

SO MUCH MORE.

Sreeja Kartha

Program for Leadership Development 2011

Dr. Michael Jaff

General Management Program 2010

The worlds top executives often need to step outside their organizations

to acquire the skills, knowledge, and leadership to successfully address

todays critical business issues. The comprehensive leadership programs

at Harvard Business School Executive Education are where they convene.

Email us at clp_info@hbs.edu or visit www.exed.hbs.edu/pgm/clp/

Learn More

The articles in this issue address

three major disruptions that have

taken place in recent years: the

rise of newly competitive emerg-

ing economies, the near collapse

of an overreaching financial sector,

and the business modeldissolv-

ing maturation of computer tech-

nology. As anyone who has lived

through a disruptive event knows, it

takes a special skill to lead during

the period that follows. You must

manage through the aftershocks,

while recovering and help others

recover a belief in building for

the future.

Before his untimely death in

April 2010, C.K. Prahalad was a

great scholar of disruption. We are

proud to publish in this issue an

article he was working on with ex-

ecutive Hrishi Bhattacharyya, who

completed it (page 54). It describes

a business model with the flexibility

and power to manage the burgeon-

ing consumption and competition

in emerging markets.

In Competing for the Global

Middle Class (page 62), s+b con-

tributing editor Edward Tse, along

with his Booz & Company col-

leagues Bill Russo and Ronald

Haddock take that theme further

by explaining how new markets

generate new competitors. And in

The New Web of World Trade

(page 70), Booz & Company senior

partners Joe Saddi, Karim Sabbagh,

and Richard Shediac trace another

group of aftershocks the evolu-

tion of capital, trade, and talent

flow among emerging economies,

with the Gulf states taking the lead.

As for the economic disruption,

one ongoing aftershock is the long

cycle of seemingly intractable un-

employment. In Manufacturings

Wake-Up Call (page 30), Booz &

Company manufacturing experts

Arvind Kaushal, Thomas Mayor,

and Patricia Riedl trace one choice

facing the United States: Ignore

manufacturing and watch the na-

tions prosperity decline, or take the

radical steps needed to revitalize it.

For counterpoint, we feature com-

mentator Clyde Prestowitz (page

10) on competitiveness, University

of Michigan professors Wally Hopp

and Roman Kapuscinski (page 36)

on manufacturing education, Kaj

Grichnik and Jerome Pellan on the

dilemma facing France (page 40),

and Brian Collie, Scott Corwin,

and Patrick Mulcahy on the outlook

for the U.S. auto industry (page 6).

The technological disruption

is covered by researchers Tom Igoe

and Catarina Mota in A Strategists

Guide to Digital Fabrication (page

44), wherein they tour this remark-

able aftershock of the IT revolution.

To pull all this together, see

executive editor Rob Nortons inter-

view with Sylvia Nasar, whose book

Grand Pursuit: The Story of Eco-

nomic Genius (Simon & Schuster,

2011) recounts the many ways in

which disruptions have been shaped

by economic theories (page 80).

Youll see some changes in

our masthead this quarter. Staff-

ers Jonathan Gage, Alan Shapiro,

and Chris Bojanovich have moved

on. We wish them all well, and

welcome Gretchen Hall, Charity

Delich, and Bevan Ruland in their

new roles. Further changes, includ-

ing new features like comments, are

happening on s+bs website, www

.strategy-business.com. In print and

online, we will continue to seek out

insights into the disruptions, the af-

tershocks, and the rebuilding that

hopefully follows.

Art Kleiner

Editor-in-Chief

kleiner_art@strategy-business.com I

l

l

u

s

t

r

a

t

i

o

n

b

y

L

a

r

s

L

e

e

t

a

r

u

Disruption and Its Aftershocks

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

e

d

i

t

o

r

s

l

e

t

t

e

r

1

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

e

d

i

t

o

r

s

l

e

t

t

e

r

LEADING IDEAS

Is the U.S. Auto Industry

Ready for Growth?

Brian Collie, Scott Corwin, and Patrick Mulcahy

The outlook for manufacturers and suppliers may be

bullish, but a new survey shows that industry execu-

tives see big challenges ahead.

The Case for Intelligent

Industrial Policy

Art Kleiner, Arvind Kaushal, and Thomas Mayor

Economic strategist Clyde Prestowitz argues for

better support for manufacturing.

How to Prepare for a Black Swan

Matthew Le Merle

Disrupter analysis can help assess the risks of future

catastrophic events.

10 Clues to Opportunity

Donald Sull

Market anomalies and incongruities may point the

way to your next breakthrough strategy.

DATA POINTS

Finding Shoppers Where They Live

ENERGY

Renewable Energy at a Crossroads

Christopher Dann, Sartaz Ahmed, and Owen Ward

The wind, solar, biomass, and geothermal sector

has grown in ts and starts and is now poised to

become a self-sustaining industry.

HEALTHCARE

Transforming Healthcare Delivery

Joyjit Saha Choudhury, Akshay Kapur, and

Sanjay B. Saxena

As governments seek to expand services more cost-

effectively, the stakeholders must collaborate.

Correction, Issue 63:

In CEO Succession 2010: The Four Types of CEOs,

by Ken Favaro, Per-Ola Karlsson, and Gary L. Neilson,

the citations for Putting Headquarters in Its Place

should have read: Gary Neilson, Etienne Deffarges,

Paul Kocourek, and John Elting Treat, Putting Head-

quarters in Its Place: The New, Lean Global Core,

Booz Allen Hamilton white paper, 1999.

comment

20

26

19

16

14

10

6

62

44

30

COVER STORY: OPERATIONS & MANUFACTURING

Manufacturings

Wake-Up Call

Arvind Kaushal, Thomas Mayor, and Patricia Riedl

A new study shows how the decisions made

today by goods producers and policymakers will

shape U.S. competitiveness tomorrow.

Revitalizing Education for Manufacturing

Wally Hopp and Roman Kapuscinski

France Faces a Dilemma

Kaj Grichnik and Jerome Pellan

OPERATIONS & MANUFACTURING

A Strategists Guide to

Digital Fabrication

Tom Igoe and Catarina Mota

Advances in manufacturing technology point to a

decentralized, disruptive maker culture, with

implications for many forms of enterprise.

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

How to Be a Truly

Global Company

C.K. Prahalad and Hrishi Bhattacharyya

Multinationals need to integrate three strategies

customization, competencies, and arbitrage

into a more relevant business model.

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

Competing for the

Global Middle Class

Edward Tse, Bill Russo, and Ronald Haddock

How three types of companies are jockeying to

capture the loyalty of billions of new consumers.

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

The New Web of

World Trade

Joe Saddi, Karim Sabbagh, and Richard Shediac

The Gulf economies are forming partnerships

with other emerging markets, redening the

trade routes that once linked East and West.

THOUGHT LEADER

Sylvia Nasar

Rob Norton

The renowned author

discusses how the great

economists uncovered the

basic truth about progress,

prosperity, and productivity,

and the reasons you should

be careful which ideas you

listen to.

BOOKS IN BRIEF

In Pursuit of Happiness

David K. Hurst

Closing implementation gaps, the enduring

principles of high-tech success, and Toyotas crisis.

END PAGE: RECENT RESEARCH

Putting a Dollar Value on Academic

Business Research

Matt Palmquist

MBA students who attend schools where teachers

publish frequently end up earning more.

Cover illustration by Doucin Pierre

conversation features

30

36

40

44

54

62

70

80

90

96

Issue 64, Autumn 2011 Published by Booz & Company

strategy+business

www.strategy-business.com

strategy+business magazine contains only paper

products that the Forest Stewardship Council certifies

have come from well-managed forests that contribute

to conservation and responsible management.

strategy+business (ISSN 1083-706X) is published quarterly by Booz & Company Inc., 101 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10178. 2011 Booz & Company Inc. All

rights reserved. strategy+business, Booz & Company, and booz&co. are trademarks of Booz & Company Inc. No reproduction is permitted in whole or

part without written permission from Booz & Company Inc. Postmaster: send changes of address to strategy+business, P.O. Box 1724, Sandusky, OH 44871-

1724. Annual subscription rates: United States $38, Canada and elsewhere $48. Single copies $12.95. Canada Post Publications Mail Sales Agreement No.

1381237. Canadian Return Address: P.O. Box 1632, Windsor, ON, N9A 7C9. Printed in the U.S.A.

Published by Booz & Company

BOOZ & COMPANY

Chairman

Joe Saddi

Chief Executive Officer

Shumeet Banerji

Chief Operating Officer

Cesare Mainardi

Chief Marketing and

Knowledge Officer

Thomas A. Stewart

Marketing Advisory

Council

Paul Leinwand

Fernando Fernandes

Klaus-Peter Gushurst

Barry Jaruzelski

Karim Sabbagh

EDITORIAL

Editor-in-Chief

Art Kleiner

kleiner_art@

strategy-business.com

Senior Editor

Jeffrey Rothfeder

rothfeder_jeffrey@

strategy-business.com

Art Director

John Klotnia

klotnia@optodesign.com

Executive Editor

Rob Norton

norton_rob@

strategy-business.com

Senior Editor,

s+b Books

Theodore Kinni

editors@

strategy-business.com

Deputy Art Director

Jessie Clear

clear@optodesign.com

Designer

Mika Osborn

mika@optodesign.com

Managing Editor

Elizabeth Johnson

johnson_elizabeth@

strategy-business.com

Chief Copy Editor

Victoria Beliveau

editors@

strategy-business.com

Contributing Editors

Barry Adler

Edward H. Baker

Denise Caruso

Melissa Master

Cavanaugh

Tom Ehrenfeld

Senior Editor

Karen Henrie

henrie_karen@

strategy-business.com

Information Graphics

Linda Eckstein

editors@

strategy-business.com

Ken Favaro

Bruce Feirstein

Lawrence M. Fisher

Ann Graham

Sally Helgesen

William J. Holstein

Deputy Managing Editor

Laura W. Geller

geller_laura@

strategy-business.com

Assistant to the Editors

Natasha Andre

andre_natasha@

strategy-business.com

David K. Hurst

Jon Katzenbach

Tim Laseter

Gary L. Neilson

Matt Palmquist

Sheridan Prasso

Web Editor

Bridget Finn

finn_bridget@

strategy-business.com

Randall Rothenberg

Michael Schrage

Edward Tse

Christopher Vollmer

PUBLISHING

Publisher and Business

Manager

Gretchen Hall

Tel: +1 212 551 6003

Fax: +1 212 551 6732

hall_gretchen@

strategy-business.com

Circulation Director

Beverly Chaloux

Circulation

Specialists Inc.

bchaloux@circulation

specialists.com

Marketing and Client

Service Manager

Charity Delich

Tel: +1 212 551 6255

delich_charity@

strategy-business.com

Production Director

Catherine Fick

Publishing Experts Inc.

cfick@publishing

experts.com

Advertising Director

Judith Russo

Tel: +1 212 551 6250

Fax: +1 212 551 6732

russo_judy@

strategy-business.com

European Advertising

Representative

Michael Weatherall

Tel: +44 7770 232227

michael@

mwa-media.com

Advertising and PR

Coordinator

Brooke Clupper

Tel: +1 212 551 6013

Fax: +1 212 551 6732

clupper_brooke@

strategy-business.com

Business Operations

and Permissions

Bevan Ruland

Tel: +1 212 551 6159

Fax: +1 212 551 6732

ruland_bevan@

strategy-business.com

Financial Reporting

Taryn Grace Diaz-

Harrison

Editorial and

Business Offices

101 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10178

Tel: +1 212 551 6222

Fax: +1 212 551 6732

editors@strategy-

business.com

Design Services

Opto Design Inc.

153 W. 27th Street, 1201

New York, NY 10001

Tel: +1 212 254 4470

Fax: +1 212 254 5266

info@optodesign.com

Retail

Comag

Customer Service

Tel: +1 800 223 0860

Back Issues

Tel: +1 800 810 1404

Outside the U.S.,

+1 817 685 5626

Reprints

www.strategy-

business.com/reprints

Tel: +1 703 787 8044

Subscriber

Customer Services

Tel: +1 877 829 9108

Outside the U.S.,

+1 570 567 0433

customer_service@

strategy-business.com

www.strategy-

business.com/

subscriber

strategy+business

P.O. Box 634

Williamsport, PA 17703

on iPad and iPhone

Download our free App on the App Store and get instant access to the best

ideas in business with a complementary issue of strategy+business

customized feeds of s+bs award-winning content / issue archives / swipe navigation / direct article

links from table of contents / choice of magazine format or plain-text reading / social-media content

sharing through Facebook, Twitter, e-mail, and more

Published by Booz & Company

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

6

L

e

a

d

i

n

g

I

d

e

a

s

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

y

+

b

u

s

i

n

e

s

s

i

s

s

u

e

6

4

by Brian Collie, Scott Corwin, and

Patrick Mulcahy

T

o many people, the U.S.

auto industry appears to

be on the mend. After

an epic sales collapse in the wake

of the 200809 recession, General

Motors, Ford, and Chrysler were all

protable again in early 2011, and

European and Korean manufactur-

ers in the U.S. were also enjoying

strong results. Only the Japanese

transplants are facing earnings pres-

sure, as they wrestle with massive

disruptions to their global supply

chains and production facilities, due

to the earthquake and tsunami at

home. Although the U.S. has slipped

to number two behind China in

auto sales, the U.S. market is still

among the worlds most protable,

thanks to consumers enthusiasm

for high-margin luxury cars, SUVs,

and light trucks. Leading forecasters

predict that light-vehicle sales in

the U.S. will rise to more than 16

million in 2015, up from 11.6 mil-

lion in 2010.

Yet auto industry insiders them-

selves are anything but sanguine. A

Booz & Company survey of more

than 200 executives from 40-plus

automakers and suppliers revealed

more modest expectations only

13.5 million in vehicle sales in 2013

and 14.5 million in 2015. The rea-

son: By the executives own reckon-

ing, most automobile companies

have not fully gotten their manage-

rial houses in order. Almost half

of the survey respondents said that

the auto industry restructuring of

200910 did not go far enough.

Two-thirds said that automakers

and auto suppliers in general were

not yet on a path to achieving sus-

tained, full returns on invested capi-

tal. In fact, the auto executives

viewed the overall tenuousness of

their industry as so potentially seri-

ous that almost 30 percent said they

expect a major automobile company

to fail in the next two years.

For U.S. auto companies, the

bankruptcies and restructurings

as well as the stronger focus on lean

factories and new union agreements

that grew out of the recession

have signicantly reduced opera-

tional costs, sanitized balance sheets,

and eliminated health and pension

legacy expenses, or at least helped to

make them more manageable. In

many ways, however, those steps

were the bare minimum necessary

for the industry to survive the down-

turn. As Edward Tse, Bill Russo,

and Ronald Haddock suggest in

Competing for the Global Middle

Class (page 62), car sales are in-

creasing rapidly in the dynamic new

global middle class of emerging

markets but new competitors are

Is the U.S. Auto Industry

Ready for Growth?

The outlook for manufacturers and suppliers may

be bullish, but a new survey shows that industry

executives see big challenges ahead.

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

7

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

also proliferating to serve this mar-

ket. Can todays automakers con-

tinue to thrive in an industry that

will be more in ux and more com-

petitive than ever before? According

to the survey, auto executives them-

selves are not sure.

If you look at the industry be-

fore the sales downturn, it was hy-

perinated, says Ernest Bastien,

vice president of retail market devel-

opment at Toyota USA. People

were using their home equity and

easy-to-get loans to take advantage

of extraordinary incentives that were

being offered. In fact, the industry

was not as robust as it looked. Going

forward, automakers are going to

have to rely on a more fundamental

but complex equation for growth:

making the right amount of great,

high-quality cars and proving to

consumers that their brand is the

best in terms of total cost of owner-

ship, drivability, and reliability.

When asked to rank their com-

panies most critical challenges,

more than 50 percent of the manu-

facturing executives surveyed chose

increasing competitive pressure. (See

Exhibit 1.) And although Japanese,

Korean, and European rivals are

certainly formidable competitors,

the looming presence of Chinese

companies casts the largest shadow.

Fully 90 percent of these executives

said that Chinese automakers would

be making cars equal in quality to

American-made vehicles by 2021.

About half of all survey respondents,

from manufacturers and suppliers,

said this could occur by 2016. In

other words, the executives said they

believe that companies like Geely

Automobile Holdings, which ac-

quired the Volvo brand from Ford,

and BYD Company, partially

owned by Warren Buffett, will

achieve in 10 years what Toyota and

other Japanese companies took 30

years, and Korean automakers took

20 years, to do.

For auto suppliers, the future is

uncertain as well not because of

potential changes in industry dy-

namics some years down the road,

but rather because of a problem they

have struggled with for at least a de-

cade: Many nd themselves unable

to command full value for their

products. Owing to an overabun-

dance of competitors in most prod-

uct categories, many suppliers lack

the leverage to set terms with their

automaker customers that would al-

low them to earn a positive return

on their invested capital. Theyve

become, in effect, low-cost order

takers. As a result, many suppliers

nd themselves too short of cash to

invest heavily in research and devel-

opment. But that investment is im-

perative if they hope to distinguish

their products from their competi-

tors and go beyond merely selling

commodities. Not surprisingly, giv-

en the dynamics of supplier relation-

ships with the automakers, the two

most widely chosen concerns ex-

pressed by suppliers in the survey in-

volved cost position and engineering,

research, and development (ER&D)/

innovation. (See Exhibit 2, page 8.)

A products price is directly

proportional to the value it creates,

says David Johnson, chief executive

ofcer of Achates Power Inc., which

is developing an energy-efcient

engine. Any time that you arent

delivering a unique technology or

unique features that will create mar-

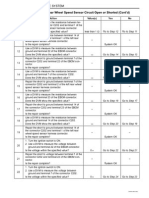

Importance of challenge (% of respondents)

Exhibit 1: Key Challenges Facing Auto Manufacturers

Survey respondents from automakers cited increasing competition, pricing, costs, and the

macroeconomic environment as most critical.

Source: Booz & Company

One of the TWO most

important challenges

One of the FIVE most

important challenges

Increasing competition 52% 76%

Pricing 28% 52%

Cost position 21% 52%

Macroeconomic situation 21% 45%

Labor relations/Legacy costs 17% 34%

Financial position 17% 31%

Product 14% 38%

Manufacturing capacity 14% 34%

Dealer capabilities 7% 28%

Regulatory requirements 3% 28%

Winning strategy 3% 21%

Management team 3% 21%

Sales and marketing 21%

Supplier relations 10%

Ninety percent of carmaker execu-

tives said Chinese automakers would

be making cars equal in quality to

American-made vehicles by 2021.

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

8

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

y

+

b

u

s

i

n

e

s

s

i

s

s

u

e

6

4

ket demand or ll a real need in the

market, your product becomes com-

moditized, and the next thing you

are doing is price and quality com-

petition. That is not a long-term

winning formula.

Clearly, suppliers have a long

way to go to improve their relation-

ships with automakers and to drive

more value into their products. But

according to the survey, auto suppli-

ers do not see the path they need

to take to get there. When asked to

name the most important keys to

winning, most suppliers did not

cite two facets of a businesss opera-

tions that routinely count among

the prerequisites for long-term via-

bility: a well-dened strategy and

deep market insight. Understand-

ably, no business leader would argue

against the importance of achieving

the low cost position or providing

superior customer service. But with-

out a well-dened strategy rooted

in deep market insight, it is nearly

impossible to achieve a sustainable,

differentiated position which,

in the end, is key to capturing the

value created.

Given the responses to the sur-

vey, and taking a close look at cur-

rent conditions in the U.S. auto in-

dustry, automakers and suppliers

face different priorities in the United

States (and elsewhere in the world).

The automakers must:

Focus even more intensely

on building attractive vehicles and

rebuilding brands. Cars and trucks

are still among the most visible,

emotional purchases consumers

make. In the current frugal and

practical environment, U.S. car buy-

ers need to be given reasons to fall

in love again.

Create vehicles with exciting

design and styling; superior quality,

reliability, and durability (QRD);

and technological innovation. Al-

though the QRD of vehicles sold in

the U.S. is better than ever, mean-

ingful gaps still exist between the

highest-ranked companies and the

rest of the pack, especially in longer-

term reliability and durability. In ad-

dition, as breakthrough innovations

in safety, connected vehicle, and

power-train technologies emerge,

new opportunities must be created

to deliver differentiated value to

consumers and drivers.

Make sure that each vehicle

produces a positive return on invest-

ment. Hoping that a few blockbust-

ers will generate most of the portfo-

lios returns as many automakers

have done in the past is no longer

sustainable in a more competitive

and smaller U.S. market.

Continue minimizing rela-

tive material and structural costs

while bringing new technology to

market cost-effectively, earning fair

returns for product innovation.

Prepare cost structures and

innovation processes for a more

globally competitive landscape.

Auto suppliers should:

Accelerate efforts to nd

greater leverage with high-quality

product lines. This means a supplier

must innovate wisely, focusing on

features that consumers are willing

to pay for, creating end-user pull,

and establishing itself as the com-

pany best positioned to help solve

manufacturers problems.

Better manage portfolios,

focusing on the markets where the

suppliers have the greatest capa-

bilities and opportunities to create

a sustained competitive advantage,

and to meet changing market needs.

Although some companies are able

to prosper making disparate compo-

nents, most do not have the resourc-

es and skills to do it well.

Continue to aggressively

manage costs. Suppliers reduced op-

erational and structural costs during

the downturn. Now, they need to

make sure that these expenses dont

creep back in as volumes ramp up.

They must also discipline themselves

to stop chasing automaker contracts

that cost more than they return

in the long run. Where possible,

suppliers and auto manufacturers

should promote collaborative cost-

based agreements that give man-

ufacturers full transparency into

relevant supplier operations and, in

exchange, allow suppliers to earn a

fair return on investment.

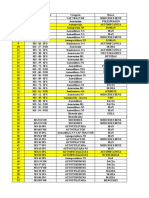

Cost position 58% 87%

ER&D/innovation 27% 69%

Macroeconomic factors 26% 67%

Customer responsiveness 22% 58%

Product 17% 62%

Undifferentiated position 16% 37%

Excess industry capacity 14% 32%

New entrants 7% 28%

Financial position 6% 29%

Market insight 4% 26%

Importance of challenge (% of respondents)

Exhibit 2: Key Challenges Facing Auto Suppliers

Survey respondents from auto industry suppliers cited improving their cost position, innovation,

and macroeconomic factors as most critical.

Source: Booz & Company

One of the TWO most

important challenges

One of the FIVE most

important challenges

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

Recognize that industry con-

solidation is likely to intensify. For

each core business, suppliers should

decide: Am I a buyer or a seller?

The U.S. auto industry is in a

period of extraordinary transition.

Whether one considers alternative

drive trains, or ways to ne-tune de-

signs and manufacturing processes,

or a raft of new global competitors,

its fair to say that only the most ex-

ible, lean, and well-managed com-

panies will survive. With that in

mind, perhaps the surveys greatest

value is its central nding: Despite

the general optimism in the auto in-

dustry today as well as the real im-

provements in efciency, quality,

and lean practices that have been

made, many executives are still brac-

ing for further change. They will

need all the courage, and skill, they

can muster. +

Reprint No. 11301

Brian Collie

brian.collie@booz.com

is a principal with Booz & Company in

Chicago. He specializes in working with

automotive and industrial clients in the

areas of business unit transformation, new

market entry, and corporate strategy.

Scott Corwin

scott.corwin@booz.com

is a partner with Booz & Company based in

New York. He has extensive experience in

assisting clients in developing creative and

pragmatic growth strategies for the auto-

motive, media, and consumer industries.

Patrick Mulcahy

patrick.mulcahy@booz.com

is a senior associate with Booz & Company

based in Cleveland. He focuses on product

strategy and M&A for automotive and

industrial clients.

For a detailed analysis of this survey, see

Facing New Realities: What Comes Next

for the U.S. Auto Industry: www.booz.com/

media/uploads/Facing_New_Realities.pdf.

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

10

P

h

o

t

o

g

r

a

p

h

c

o

u

r

t

e

s

y

o

f

C

l

y

d

e

P

r

e

s

t

o

w

i

t

z

his work since his rst major book,

Trading Places: How We Are Giving

Our Future to Japan and How to Re-

claim It (Simon & Schuster, 1988).

He sat down with strategy+business

at the Manufacturing Executives

Forum, which Booz & Company

conducted in Chicago in May 2011.

S+B: How did you come to realize the

signicance of manufacturing to

economic vitality?

PRESTOWITZ: I grew up in a manu-

facturing environment. My dad

worked in the steel products indus-

try, and I visited the original Bethle-

hem steel mill many times as a boy.

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation

started to consistently lose money in

the early 1980s; it declared bank-

ruptcy in 2001 and closed in 2003.

The old steel mill was then replaced

with a casino. The passage from

steel mill to casino says a lot about

the trajectory of the U.S. economy,

and about the declining quality of

life for the middle class when there is

no manufacturing base.

Manufacturing, more than oth-

er activities, is critical to prosperity

because it generates economies of

scale. It also sparks innovation,

wholly new products and industries.

And it has great multiplier effects:

Every factory needs accountants,

sandwich shops, component suppli-

ers, and other services. One dollar

invested in manufacturing creates

two dollars or more of income for

ancillary industries. By contrast, a

dollar invested in retail creates about

45 cents of additional income.

Finally, international trade

overwhelmingly involves goods.

When countries like the United

States have trade decits, they are

primarily in manufactured goods.

Those trade decits take away jobs.

If you want to get those jobs back,

theres only one way: Youve got to

support manufacturing.

I remember, back in the 1980s,

debating about whether to subsidize

the American aircraft industry

against the European upstart Air-

bus. George Shultz [then secretary

of state] said that the Europeans, by

subsidizing Airbus, were only hurt-

ing themselves taxing people to

pour money down a corporate rat-

hole. Even if he was right, he was

ignoring the damage done to our

aircraft industry in the U.S. and

the people employed by it, directly

and indirectly. Any country that

wants to survive needs to focus on

the industries that it wants to keep,

and support them wholeheartedly.

For the past 25 years, U.S. eco-

nomic policy has been driven by

The Case for Intelligent

Industrial Policy

Economic strategist Clyde Prestowitz argues for

better support for manufacturing.

by Art Kleiner, Arvind Kaushal,

and Thomas Mayor

S

tarting with his role as an

advisor to the secretary of

commerce in the Reagan

administration in the 1980s, and

progressing to his current position as

founder and president of the Eco-

nomic Strategy Institute in Wash-

ington, D.C., Clyde Prestowitz has

been a consistent voice on the im-

portance of manufacturing in eco-

nomic competitiveness. Although

the title of his most recent book, The

Betrayal of American Prosperity: Free

Market Delusions, Americas Decline,

and How We Must Compete in the

Post-Dollar Era (Free Press, 2010),

might seem alarmist to a global au-

dience, Prestowitzs perspective is

nuanced and oriented toward fun-

damentals. He argues for sustained

industrial policy at a national level:

for marshaling the forces of business

leaders, government ofcials, labor

unions, and academics for the sake

of building economic competitive-

ness and (especially) a strong and

distinctive manufacturing base. He

also argues that the global economy

is more likely to thrive when more

countries manage their economies

this way, competing wholeheartedly

even as they trade avidly.

Prestowitz focuses on manufac-

turing in the U.S.; its decline and

revitalization have been a theme in

MIKA: PLS PLACE SPECTRAS HIRES

WHEN AVAILABLE

Clyde Prestowitz

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

consumer welfare, by trying to

achieve the greatest variety of goods

at the lowest prices, without any fo-

cus on producers. This combines

with the notion that it doesnt mat-

ter what we make, or how we make

it, because globalization will even

things out in the end. One top of-

cial once said to me, Clyde, dont

worry. The Japanese will sell us cars,

and well sell them poetry. But now

we need jobs, and for that, we need

manufacturing.

S+B: For executives of multinational

companies, it might seem counterin-

tuitive to focus on the prosperity of

their home country as opposed to

global economic growth.

PRESTOWITZ: I agree that its wrong

for the U.S., or any other country, to

adopt a zero-sum mentality. For ex-

ample, a rich and dynamic China

can be of great benet to the United

States but not necessarily. It de-

pends to a tremendous extent on

what kinds of policies the two coun-

tries adopt.

The conventional economic

view is that unfettered global free

trade will automatically produce op-

timal results that Chinas gains

will also be the United States gains,

and vice versa. But that view is based

on simplistic assumptions: no econ-

omies of scale, no transfer of tech-

nology or capital across borders.

Paul Krugman won a Nobel Prize

largely because he pointed out the

problems with these assumptions.

There are two kinds of global

companies. In the United States, the

purpose of the corporation is pri-

marily to provide optimal returns to

shareholders. This leads to a focus

on optimizing short-term results. In

continental Europe and most of

Asia, the state charters the corpora-

tion and gives it a lot of specic ben-

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

12

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

y

+

b

u

s

i

n

e

s

s

i

s

s

u

e

6

4

ets; in exchange, the corporation

provides benets to society. This

leads naturally to embracing a co-

herent industrial policy.

S+B: What do you mean by a coher-

ent industrial policy?

PRESTOWITZ: Theres a lot of mis-

understanding about this. Its associ-

ated with preWorld War II Britain

and France, whose governments

supported particular companies as

national champions. People assume

it means having governments pick

winners and losers.

Look instead at countries like

Singapore, Sweden, Taiwan, Ger-

many, Korea, Switzerland, Finland,

and China. Theyre all very differ-

ent; some are democratic, others are

authoritarian. The Finns and Swedes

have strong labor unions, whereas

unions in Taiwan and Singapore are

weak. But all these countries are ec-

onomically successful for the same

reasons. First, their governments fo-

cus on being competitive by pro-

moting selected high-value-added

industries, with a long planning ho-

rizon. Second, they have a high level

of coordination among the govern-

ment, labor unions, and business

management, in investment deci-

sions, wages, and ination rates.

They dont pick winning compa-

nies; instead, they build a consensus

on what each of them has to do to

contribute [to building a vibrant in-

dustry]. Compared to other coun-

tries that have taken a more laissez-

faire approach, their performance is

far superior.

S+B: This approach implies a very

nuanced attitude toward economic

policy being neither all open nor

all closed.

PRESTOWITZ: Absolutely. It means

you have to think about how you in-

vest. President Obama is currently

[in June 2011] putting money into

developing green energy. Thats ad-

mirable, but the amount is relatively

small compared with the massive

programs supporting the same in-

dustries in China, Japan, Korea,

Germany, and Denmark. And pro-

ducers of green energy products in

those countries have free access to

the U.S. market, with much bigger

scale than the U.S.-based producers

have, because their governments

have created much bigger projects. If

the U.S. really wants to create a via-

ble green industry, it will take more

money but money is not enough.

U.S. policies for trade, investment,

and research and development all

have to t together, taking into con-

sideration what other countries are

doing, and nding a few niches in

which to develop dominance.

S+B: Is there a good model of some

sector that has made this kind of in-

vestment work?

PRESTOWITZ: The American semi-

conductor industry has handled it-

self very well over the years. In the

1980s, it was weakened by Japanese,

Korean, and Taiwanese competitors,

all supported by their countries

industrial policies. U.S. industry

leaders explained it to the requisite

ofcials in the U.S. Commerce De-

partment and persuaded them to

act. The result was the U.S.Japan

Semiconductor Agreement of 1986;

it effectively guaranteed U.S. pro-

ducers 20 percent of the Japanese

market and prevented Japanese

dumping [selling underpriced goods

to drive out competition] in the U.S.

market. That was a sensible policy. It

was followed by similar agreements

with Korea and others.

Also in 1987, the government

and 14 companies launched Sema-

tech (the name Sematech derived

from Semiconductor Manufactur-

ing Technology), which was a

50/50 governmentindustry consor-

tium aimed at maintaining the com-

petitiveness of U.S. semiconductor

equipment manufacturers. [In 1994,

Sematechs board voted to discon-

tinue federal support on the grounds

that the U.S. semiconductor indus-

try had fully recovered; the organi-

zation continues today as an interna-

tional innovation consortium.]

S+B: What do you say to business or

government leaders who, rightly or

wrongly, dont trust one another

enough to act this way?

PRESTOWITZ: It should not be that

difcult a problem. Industry needs

government all the time often in

ways that it doesnt fully acknowl-

edge. I hear CEOs talking about

how they hate to go to Washington,

and how U.S. taxes are too high. At

the same time, they want Washing-

ton to do more to protect their intel-

lectual property from appropriation

by Chinese companies. They com-

plain about the ofcial buy China

rules [forcing companies that want

to sell goods in China to produce

there]. And to whom do they com-

Successful governments promote

selected high-value industries, with

a long planning horizon.

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

13

plain? To the U.S. government.

An astute government ofcial

would take advantage of this situa-

tion. He or she would do more

to enforce international intellectual

property rules, and respond more

ercely to Chinas innovation poli-

cies [in which countries entering

China are forced into R&D-sharing

joint ventures]. But the ofcial

would also say to the CEO, Im

taking care of my part of the deal,

but you need to think more broadly

as well.

S+B: Youre asking for sweeping

changes in the way some policymak-

ers think. How do we get from here

to there, especially in a very partisan

political climate?

PRESTOWITZ: It probably takes a

crisis. I think the last economic crisis

wasnt bad enough to force the

changes we need. We should have

nationalized the banks or gotten rid

of their management. The bankers

should have taken a haircut. And we

should have much more discipline

on Wall Street.

The world is going to be tough-

er for Americans than it was be-

tween 1945 and 2000, when the

U.S. had absolute economic domi-

nance. That wasnt normal; were

just getting back to normal now. But

within that new normal, I have great

condence that the United States

can maintain a high and rising stan-

dard of living. If I think of the glob-

al economy like a game of bridge, I

think the U.S. has a better hand of

cards than any other player: better

than the European Union, Japan,

China, or India. But as any bridge

player knows, its very possible to

have good cards and lose if you dont

play the cards well. The U.S. has not

been playing its cards well for quite

some time. If we change the quality

of our game, we wont have to be-

grudge Chinas success or the

success of Brazil, India, or anyone

else. We can all be successful. +

Reprint No. 11302

Art Kleiner

art.kleiner@booz.com

is editor-in-chief of strategy+business.

Arvind Kaushal

arvind.kaushal@booz.com

is a partner with Booz & Company

in Chicago. He leads the rms North

American manufacturing team.

Thomas Mayor

thomas.mayor@booz.com

is a Booz & Company senior executive ad-

visor based in Cleveland, where he focuses

on developing operations strategies and

leading business transformation programs

for the global aerospace, automotive, and

industrial sectors.

by Matthew Le Merle

A

number of unexpected ca-

tastrophes and shortages

dominated the headlines

in the rst quarter of 2011. Japan

was hit by a magnitude 9.0 earth-

quake and tsunami that caused a

nuclear disaster, persistent power

outages, and a host of other major

societal and economic challenges.

China sharply tightened its limits on

exports of rare earth minerals, on

which the information technology,

automotive, and energy industries

rely. The nations of the Middle East

and North Africa experienced severe

political eruptions, including civil

war in Libya and regime-shaking

protests in Algeria, Egypt, Iraq,

Jordan, Syria, and Tunisia, which

pushed oil prices above US$100 per

barrel. Portugal and Greece tottered

on the edge of insolvency, destabiliz-

ing their political leaders. Christ-

church, New Zealand, was hit by

two major earthquakes in quick suc-

cession, and the state of Queensland

in Australia suffered the worst oods

in recorded history in at least six

river systems, resulting in great so-

cial and economic disruption.

All these events are examples of

the kinds of high-magnitude, low-

frequency upheavals that Nassim

Nicholas Taleb labeled black swans,

after a historical reference to their

improbability. In The Black Swan:

The Impact of the Highly Improbable

(Random House, 2007), Taleb de-

ned a black swan as an event with

the following three attributes. First,

it is an outlier, as it lies outside the

realm of regular expectations, be-

cause nothing in the past can con-

vincingly point to its possibility.

Second, it carries an extreme im-

pact. Third, in spite of its outlier

status, human nature makes us con-

coct explanations for its occurrence

after the fact, making it explainable

and predictable.

Whether environmental, eco-

nomic, political, societal, or techno-

logical in nature, individual black

swan events are impossible to pre-

dict, but they regularly occur some-

where and affect someone. Some

observers argue that the frequency

of these events is increasing; others

say global communication networks

have simply made us more aware of

them than we were in the past.

In any case, with the rise of

global business, it is likely that black

swans carry increased risks for your

company, including negative im-

pacts on your customers, suppliers,

partners, assets, operations, employ-

ees, and shareholders. Today, not

only can a catastrophe in one part of

the world affect the sourcing, manu-

facture, shipping, and sale of prod-

ucts locally, but the interconnections

of global nancial, economic, and

political networks ensure that the ef-

fects of such events ripple around

the world.

ERM Is Not Enough

Typically, a large company relies on

its enterprise risk management

(ERM) department to identify po-

tential business disruptions, map

out their most likely effects, and de-

velop mitigation plans and preven-

tive actions to reduce the risk expo-

sures. After the multiple and severe

disruptions of the past decade, start-

ing with the terrorist attacks of

September 11, 2001, the ERM func-

tions at most companies have be-

come well staffed with risk manag-

ers who work diligently to protect

their company across strategic, op-

erational, nancial, and hazard risk

categories. Through this process,

ERM has become an indispensable

member of the global functional

teams in most large companies.

Most ERM groups focus their

attention on the risks that businesses

most frequently encounter such

as whether the enterprise is comply-

ing with regulations, suitably ac-

counting for its activities, and oper-

ating in an ethical and legal manner

rather than on black swans. And

this approach is appropriate. First,

ERM resources are limited and

must be invested in mitigating high-

frequency risks, as well as servicing

the growing demands imposed by

Sarbanes-Oxley and other nancial

and regulatory requirements. Sec-

ond, high-magnitude, low-frequen-

cy events can stem from sources too

numerous and too varied for the

ERM team to identify in full. Third,

the internal politics and culture of

many large companies unintention-

ally create blind spots that can be

very difcult to penetrate for inter-

nal staff members using standard

ERM tools.

How to Prepare for a

Black Swan

Disrupter analysis can help assess the risks of

future catastrophic events.

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

14

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

y

+

b

u

s

i

n

e

s

s

i

s

s

u

e

6

4

stand black swans.

The analysis consists of a four-

step process that will be familiar to

professional ERM managers. It

quickly and efciently maps the

shape of the enterprise, determines

the breadth of potential disrupters,

asks the what ifs to determine how

severely certain events could stress

the enterprise, and then implements

the contingency plans.

1. Mapping the enterprise. The

shape of a company is determined

by a number of factors, starting with

its geographic footprint, its opera-

tions, the composition and con-

struction of its supply chain, and its

channel partners and customers. In

mapping these elements, it is impor-

tant to look beyond rst-order rela-

tionships. Recently, for example,

Apples supply of lithium-ion batter-

ies, used in iPods, suddenly dried

up. Unfortunately, as Apple quickly

discovered, almost all its suppliers

purchased a critical polymer used to

make the batteries from the Kureha

Corporation, a Japanese company

whose operations were disrupted by

the March 11 earthquake. In fact,

Kurehas share of the global market

for polyvinylidene uoride, which is

used as a binder in lithium-ion bat-

teries, is 70 percent. This is why ana-

lysts must also map second-order

relationships (the suppliers of the

companys suppliers). In some criti-

cal cases, even third-order relation-

ships should be mapped.

After the shape of the enterprise

has been mapped with the help of

the ERM staff, nance and other

group functions participate in team

sessions to map sources and concen-

trations of revenue, prot, and capi-

tal. Then the often-hidden concen-

trations that exist in go-to-market

activities including the businesss

products, services, channels, and

customers are considered.

A determination of the com-

panys shape must also include a

mapping of industry structure and

competitive dynamics, as well as the

rms position in both. To deter-

mine how a black swan event could

stress a company, the team needs to

understand the foundation on which

the status quo rests.

2. Creating the disrupter list.

The key to creating a list of potential

black swan events is to cast a wide

net by cataloging possible cata-

strophic environmental, economic,

political, societal, and technological

events. The team should add much

more to the list than ERM typically

does, and continue until the net is

wide enough to include representa-

tives of as many different black swan

categories as possible.

After the long list is compiled,

the events are categorized by the

type of impact they might have on

the business. The result is a shorter,

more workable synthesis that encap-

sulates the black swan events that

could threaten the company.

Thus, most ERM teams can as-

sure their board and executive team

that they have covered the more

common risk areas of compliance,

ethics, nance, and accounting, as

well as safety, quality, and customer

experience. But ERM simply does

not have the capacity to also moni-

tor high-magnitude, low-frequency

disrupters on a continuous or regu-

lar basis.

This does not mean that black

swans can or should be ignored.

These events can threaten a com-

panys survival, and boards and

senior leaders are responsible for

protecting shareholders and other

stakeholders. They must ask, What

else can go wrong?

A Disrupter Analysis Stress Test

The solution to this conundrum is

disrupter analysis. Disrupter analy-

sis does not seek to predict black

swans; that cannot be done. And it

is not meant to replace ERM, but

rather to complement it. Disrupter

analysis which is typically con-

ducted by a separate team working

in collaboration with the ERM staff,

functional and business unit leaders,

and senior management is de-

signed to periodically administer a

stress test to a large company in

order to assess its ability to with-

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

3. Asking what if. Armed with

the enterprise map and a concise list

of disruptive events, the analysis

team can begin to ask what would

happen to the company if the events,

or even combinations of events, oc-

curred. The likelihood of occur-

rence is not a major concern here;

these are, after all, black swans.

Rather, the team needs to determine

the relative impact and consequenc-

es of a given catastrophe.

This stage of the analysis often

produces surprising results. Revela-

tions can include greater concentra-

tions of risk than were previously

recognized, more severe and unex-

pected consequences, and, some-

times, seemingly obvious mistakes

in how an enterprise has been

shaped. The widespread adoption of

offshoring strategies has spawned

one example. At rst, offshoring

spread out the exposures and risks

of operational disruptions because

large companies were expanding

their ranks of partners and their

geographic footprints. But more re-

cently, new exposures have arisen:

Offshoring has created greater con-

centrations of risk in far-ung loca-

tions, where high-magnitude, low-

frequency risks are often more varied

and where the likelihood of rapid

recovery can be much lower. Con-

sider what might happen to the

worlds consumer electronics and

apparel industries, for example, if

the recent labor unrest in southern

Chinese factories develops into a

disruptive labor movement similar

to what the West experienced dur-

ing the early 20th century.

4. Implementing contingency

plans. Typically, the analysis team

systematically generates mitigation

options for each major what if in-

sight. It looks for options that ad-

dress multiple risks, and prioritizes

them by the magnitude of risk expo-

sure as well as the expense and ease

of implementation.

Sometimes companies complete

this nal step on their own, using

their ERM departments. The ERM

staff usually participates throughout

the analysis and is the most logical

and effective group to shore up any

major exposures. However, some-

times internal complexities warrant

third-party involvement. Also, most

boards prefer to involve an external,

objective set of eyes, especially when

recommendations include critical

strategic and operational issues.

No company can be completely

prepared for every possible black

swan event. But the board, the ex-

ecutive team, and the ERM staff

can complement the day-to-day

work of the ERM function with pe-

riodic disrupter analyses. These

analyses can ensure that the com-

pany has adequately focused its at-

tention on high-magnitude, low-

frequency events, performed stress

tests on its tness in the face of such

events, and prepared itself for unex-

pected catastrophes. +

Reprint No. 11303

Matthew Le Merle

matthew.lemerle@booz.com

is a partner with Booz & Company based

in San Francisco. He works with leading

technology, media, and consumer

companies, focusing on strategy, corporate

development, marketing and sales,

organization, operations, and innovation.

10 Clues to Opportunity

Market anomalies and incongruities may point the

way to your next breakthrough strategy.

by Donald Sull

D

uring their heyday in

the late 19th and early

20th centuries, transatlan-

tic cruise lines such as the Hamburg

America Line and the White Star

Line transported tens of millions of

passengers between Europe and

the United States. By the 1960s,

however, their business was being

threatened by the rise of a disruptive

new enterprise, namely, nonstop

transatlantic ights. As it happened,

the cruise ship lines had one poten-

tial strategy with which to save their

business: vacation cruises. Starting

in the 1930s, some of these lines

had sailed to the Caribbean during

the winter, thus using their boats

when rough seas made the Atlantic

impassable. And in 1964, when a

new port was opened in Miami,

Fla., the pleasure cruise business be-

gan to boom.

But the great cruise lines missed

this breakthrough opportunity.

They saw their protability fall

while dozens of startups, including

Royal Caribbean and Carnival, ret-

rotted existing ships to offer plea-

sure cruises and built an entirely

new travel and leisure category that

continues to grow today.

Managers and entrepreneurs

walk past lucrative opportunities all

the time, and later kick themselves

when someone else exploits the strat-

egy they overlooked. Why does this

happen? Its often because of the

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

16

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

y

+

b

u

s

i

n

e

s

s

i

s

s

u

e

6

4

natural human tendency known to

psychologists as conrmation bias:

People tend to notice data that con-

rms their existing attitudes and be-

liefs, and ignore or discredit infor-

mation that challenges them.

Although it is difcult to over-

come conrmation bias, it is not

impossible. Managers can increase

their skill at spotting hidden oppor-

tunities by learning to pay attention

to the subtle clues all around them.

These are often contradictions, in-

congruities, and anomalies that

dont jibe with most of the prevail-

ing assumptions about what should

happen. Here is my own top 10

eld guide to clues for hidden break-

through opportunities, observed in

a wide variety of industries, coun-

tries, and markets. If you nd your-

self noticing one or more of them, a

major opportunity for growth could

be lurking behind it.

1. This product should already

exist (but it doesnt). As the accesso-

ries editor for Mademoiselle maga-

zine in the early 1990s, Kate Brosna-

han spotted a gap in the handbag

market between functional bags

that lacked style and extremely ex-

pensive but impractical designer

bags from Herms or Gucci. Bros-

nahan quit her job, and with her

partner Andy Spade, founded Kate

Spade LLC, which produced fabric

handbags combining functionality

and fashion. These attracted the at-

tention of celebrities such as Gwyn-

eth Paltrow and Julia Roberts. Many

well-known product innovations

including the airplane, the mobile

phone, and the tablet computer

began similarly, as products that

people felt should already exist.

2. This customer experience

doesnt have to be time-consuming,

arduous, expensive, or annoying (but

it is). Consumer irritation is a reli-

able indicator of a potential oppor-

tunity, because people will typically

pay to make it go away. Reed Hast-

ings, for example, founded Netix

Inc. after receiving a US$40 late fee

for a rented videocassette of Apollo

13 that he had misplaced. Charles

Schwab created the largest low-cost

brokerage house because he was

fed up with paying the commissions

of conventional stockbrokers. Scott

Cook got the idea for Quicken after

watching his wife grow frustrated

tracking their nances by hand.

3. This resource could be worth

something (but it is still priced low).

Sometimes an asset is underpriced

because only a few people recognize

its potential. When a low-cost air-

line such as easyJet or Ryanair an-

nounces its intention to y to a new

airport, real estate investors often

leap to buy vacation property near-

by. They rightfully expect a jump in

real estate values. Similarly, the

founders of Infosys Technologies

Ltd., Indias pioneering provider of

outsourced information technology

services, were among the rst to rec-

ognize that Indian engineers, work-

ing for very low salaries, could pro-

vide great value to multinational

clients. The company earned high

prots on the spread between what

they charged clients and what they

paid local engineers.

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

17

I

l

l

u

s

t

r

a

t

i

o

n

b

y

S

t

e

f

a

n

i

e

A

u

g

u

s

t

i

n

e

4. This discovery must be good

for something (but its not clear what

that is). Researchers sometimes rec-

ognize that they have stumbled on a

promising resource or technology

without knowing the best uses for it

right away. The resulting search for a

problem to solve can lead to great

protability. One example was the

founding of the ArthroCare Corpo-

ration, a $355 million producer of

medical devices based on a process

called coblation, which uses radio

frequency energy to dissolve dam-

aged tissue with minimal effect on

surrounding parts of the body. Med-

ical scientist Hira Thapliyal, who

codiscovered this process, founded a

company to offer it for cardiac sur-

gery, but that market turned out to

be too small and competitive to sup-

port a new venture. Undeterred, he

looked for other potential uses, and

found one in orthopedics, where

there are more than 2 million ar-

throscopic surgeries per year.

5. This product or service should

be everywhere (but it isnt). Some-

times people chance upon an attrac-

tive business model that has failed to

gain the widespread adoption it de-

serves. Two archetypal retail food

stories illustrate this. In 1954, res-

taurant equipment salesman Ray

Kroc visited the McDonald broth-

ers hamburger stand in southern

California, and convinced them to

franchise their assembly-line ap-

proach to ipping burgers. In 1982,

coffee machine manufacturing ex-

ecutive Howard Schultz visited a

coffee bean producer called Star-

bucks in Seattle. He recognized the

potential of a chain restaurant based

on European coffee bars, and he

joined Starbucks, hoping to con-

vince the companys leadership to

convert their retail store to this

format. When they didnt, he start-

ed his own coffeehouse chain, later

buying the Starbucks retail unit as

the core of his new business.

6. Customers have adapted our

product or service to new uses (but

not with our support). Chinese appli-

ance maker Haier Group discovered

that customers in one rural province

used its clothes washing machines to

clean vegetables. Hearing this, a

product manager spotted an oppor-

tunity. She had company engineers

install wider drain pipes and coarser

lters that wouldnt clog with vege-

table peels, and then added pictures

of local produce and instructions on

how to wash vegetables safely. This

innovation, along with others in-

cluding a washing machine designed

to make goats-milk cheese, helped

Haier win share in Chinas rural

provinces, while avoiding the cut-

throat price wars that plagued the

countrys appliance industry.

7. Customers shouldnt want

this product (but they do). When

Honda Motor Company entered the

U.S. motorcycle market in the late

1950s, it expected to sell large mo-

torcycles to leather-clad bikers. De-

spite a concerted effort, the compa-

ny managed to sell fewer than 60 of

its large bikes each month, far short

of its monthly sales goal of 1,000

units. Then a mechanical failure

forced the company to recall these

models. In desperation, it promoted

its smaller 50cc motorbike, the Cub,

which Honda executives had as-

sumed would not interest the U.S.

market. When the smaller bikes sold

well, Honda realized it had discov-

ered an untapped segment looking

for two-wheel motorized transporta-

tion. (The campaign is still remem-

bered for its catchphrase, You meet

the nicest people on a Honda.)

8. Customers have discovered a

product (but not the one we offered).

Joint Juice, a roughly $2 million

company that produces an easy-to-

digest glucosamine liquid, was

founded by Kevin Stone, a promi-

nent San Francisco orthopedic sur-

geon. He learned about the nutrient

from some of his patients, who took

it for joint pain instead of the ibu-

profen he had prescribed. Many

doctors might have ignored this or

even scolded their patients for fall-

ing prey to fads, but Stone recog-

nized he might be missing some-

thing. He looked up the clinical

research on glucosamine in Europe,

where it was the leading nutritional

supplement. (Veterinarians, he dis-

covered, swore by it, and their

patients fell for neither fads nor

placebos.) Then he built a business

around it.

9. This product or service is

thriving elsewhere (but no one offers

it here). In the early 1990s, a Swed-

ish business student named Carl Au-

gust Svensen-Ameln tried to store

some of his belongings in Sweden

while at school in Seattle, but found

that all the local self-storage facilities

were full. He studied the storage in-

dustry, already prevalent in the

United States, and discovered a

business model characterized by

high rents, low turnover, and negli-

gible operating costs. Yet self-stor-

age, at the time, was virtually non-

existent in continental Europe.

Svensen-Ameln and a friend from

business school set up a partnership

with an established U.S. company,

Shurgard Storage Centers Inc. The

resulting company, European Mini-

Storage S.A., was the rst of several

such companies that Svensen-Ameln

started in Europe, to great success.

10. That new product or service

shouldnt make much money (but it

does). Established competitors are

often surprised when upstart rivals

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

18

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

y

+

b

u

s

i

n

e

s

s

i

s

s

u

e

6

4

do well. In his 2008 book, The Part-

nership: The Making of Goldman

Sachs (Penguin Press), Charles D.

Ellis noted that for decades, Gold-

man Sachs partners had avoided in-

vestment management, which they

believed generated lower fees than

trading and investment banking.

When Donaldson, Lufkin & Jen-

rette Inc. published its nancial

performance as part of a 1970 stock

offering, Goldman partners were

startled to learn that fees and bro-

kerage commissions on frequent

trades added up to a highly prot-

able business. Shortly thereafter,

Goldman expanded into managing

corporate pension funds, and ag-

gressively built its business.

Incongruities like these can of-

fer a critical clue about where your

assumptions no longer match real-

ity. From there, you are more likely

to uncover the kinds of opportuni-

ties that you might otherwise have

missed and that your competitors

still dont recognize. Start by asking

yourself, What are the most unex-

pected things happening in our

business right now? Which competi-

tors are doing better than expected?

Which customers are behaving in

ways we hadnt anticipated? Take

yourself through the list of top 10

clues. Leaders who consistently no-

tice and explore anomalies increase

the odds of spotting emerging op-

portunities before their rivals. +

Reprint No. 11304

Donald Sull

dsull@london.edu

is a professor of strategic and international

management at the London Business

School, where he is also the faculty

director for executive education. His books

include The Upside of Turbulence: Seizing

Opportunity in an Uncertain World (Harper

Business, 2009).

40% 20%

0 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Shopper Marketing

Social Media

Internet Brand

Advertising

Mobile Marketing

Owned Media

Paid Search

Print Media

Other Paid Media

Television

Consumer Promotions

Trade Promotions

BY MORE THAN 5%

BY 0 TO 5%

Will DECREASE Spending

BY MORE THAN 5%

BY 0 TO 5%

Will INCREASE Spending

Expected Growth in CPG Manufacturers Advertising and Promotion Mix

Average Annual Change, 20112014

DATA POINTS

Finding Shoppers

Where They Live

In consumer packaged goods (CPG), shopper marketing

efforts to observe and inuence consumers at the time of

purchase is one of the hottest and fastest-growing activities

in advertising and promotions. Shopper marketing includes

in-store shelf displays, digital kiosks, shopping list apps,

e-coupons, and more, all of which generate digital data that

marketers can use to further rene their pitches. In a recent

Booz & Company survey of senior CPG executives, 83 percent

of respondents said their companies plan to increase their

investments in shopper marketing, and a majority (55 percent)

ranked it as their number one investment, with plans to boost

spending more than 5 percent per year, followed close behind

by several forms of online media spending, while traditional,

ofine activities are in decline.

Note: Figures exclude neutral responses.

Source: Grocery Manufacturers Association/Booz & Company Survey of CPG

Manufacturers and Retailers, Summer 2010 (manufacturer responses only)

Link to full report: www.booz.com/shopper-marketing-4.0

c

o

m

m

e

n

t

l

e

a

d

i

n

g

i

d

e

a

s

19

ENERGY

by Christopher Dann, Sartaz Ahmed,

and Owen Ward

I

n 2007, renewable energy sourc-

es were poised for accelerated

growth. Then the global eco-

nomic downturn intervened, de-

pressing energy demand in general

and casting particular doubt on the

business case for wind, solar, bio-

mass, and geothermal energy. Now

that the sector is beginning to grow

again, some industry observers are

still questioning whether the market

is resilient enough to continue that

growth, considering the volatility of

energy prices and a shifting political

climate. The answer is more opti-

mistic than one might expect, be-

cause the market has evolved in sev-

eral important ways during the last

few years; it is unlikely to experience

the periods of decline or stagnation

we have seen in the past. One of the

hallmarks of the renewables sector

today is its structural diversity in

terms of technologies, players, and

geographic regions and that will

make all the difference.

The story of the new wave of