Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Drones Are Cheap, Soldiers Are Not, A Cost-Benefit Analysis of War

Hochgeladen von

Wayne McLean0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

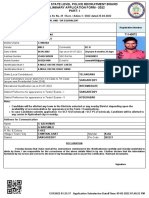

68 Ansichten3 SeitenA MQ-9 Reaper Drone has an operational cost one-fifth of the F35 Joint Strike Fighter. So should drones replace soldiers in military warfare?

Originaltitel

Drones Are Cheap, Soldiers Are Not, a Cost-benefit Analysis of War

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenA MQ-9 Reaper Drone has an operational cost one-fifth of the F35 Joint Strike Fighter. So should drones replace soldiers in military warfare?

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

68 Ansichten3 SeitenDrones Are Cheap, Soldiers Are Not, A Cost-Benefit Analysis of War

Hochgeladen von

Wayne McLeanA MQ-9 Reaper Drone has an operational cost one-fifth of the F35 Joint Strike Fighter. So should drones replace soldiers in military warfare?

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 3

Wayne McLean

Associate Lecturer, Politics and International Relations

Program at University of Tasmania

26 June 2014, 1.26pm AEST

Drones are cheap, soldiers are not: a

cost-benet analysis of war

AUTHOR

Cost is largely absent in the key debates around the use of unmanned drones in war, even

though drones are a cost-effective way of achieving national security objectives.

Many of the common objections to drones, such as their ambiguous place in humanitarian

law, become second-tier issues when the cost benefits are laid out. For strategic military

planners, cost efficiencies mean that economic outputs can be more effectively translated into

hard military power. This means that good intentions concerned with restricting the use of

drones are likely to remain secondary.

This pattern of cost-trumping-all has historical precedents. The cheap English longbow

rendered the expensive (but honourable) horse-and-knight combination redundant in the

14th century. Later, the simple and cost-effective design of the machine gun changed

centuries of European military doctrine in just a few years.

Drones are cheap

These basic principals are visible in the emergence of drones. For example, according to the

American Security Project, unclassified reports show that the MQ-9 Reaper drone used for

attacks in Pakistan has a single unit cost of US$6.48 million and an operational cost of close

to US$3 million.

This latter figure is deceptive, however, as a full drone system requires a larger infrastructure

to operate. Therefore, a typical reaper drone in a group of four on an active mission requires

two active pilots, a ground station, and a secured data link. However, even with this

A MQ-9 Reaper Drone has an operational cost one-fifth of the

F35 Joint Strike Fighter. So should drones replace soldiers in

military warfare? US Air Force

significant infrastructure requirement the end cost is US$3250 per hour of flight time.

In contrast, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter which the Australian government recently

announced it will buy 58 more of costs nearly US$91 million per unit, almost US$5 million

per year to operate and $16,500 per hour of flight.

While drones will never completely replace soldiers, this debate is becoming less important in

the current strategic climate. The operating environments where drones are deployed

countries such as Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen do not emphasise hearts and minds

strategies where the human element has traditionally been valued as a force multiplier.

Instead, objectives in these countries involve attacks on specific individuals, with operational

data obtained by signal intelligence beforehand. Human contact becomes even less desirable

given that a key tactic of combatants in these weak states is attrition with the aim of creating

low-level civil conflicts. The end goal of these actions is to inflict high economic costs to the

adversary.

As a result, this remote and analytical method of engaging militarily leads to substantial cost

efficiencies.

Soldiers are expensive

While military budgets get smaller, the cost of the human soldier remains expensive. For

example, each US solider deployed in Afghanistan in 2012 cost the government US$2.1

million.

These costs are only part of the picture, though. Thanks to medical advances, soldiers are

now more likely to survive catastrophic battleground injuries than in the past. For instance,

during the Iraq and Afghan operations there were seven injuries to each fatality compared to

2.3 in World War Two and 3.8 in World War One.

This increasing likelihood of survival means a greater need for long-term support of veterans.

US operations in the Middle East over the past 13 years have resulted in 1558 major limb

amputations and 118,829 cases of post-traumatic stress disorder. There have also been

287,911 episodes of traumatic brain injury, often caused by a soldiers close proximity to

mortar attacks.

The most serious of these injuries can incur more than 50 years of rehabilitation and medical

costs, with most victims in their early 20s. For example a typical polytrauma, where a soldier

has experienced multiple traumatic injuries, has a calculated annual health care cost of

US$136,000.

When rehabilitative hardware such as bionic legs is added which can cost up to

US$150,000 the expeditures are considerable over a lifetime. These costs also peak 30

years after conflict and therefore are rarely viewed in context of current operations.

Less severe and less obvious disabilities are even more frequent. Towards the end of 2012,

50% of US veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan (over 780,000), had filed disability claims

ranging from military sexual trauma to mesothelioma.

On top of this there are further hidden social costs: veterans account for 20% of US suicides,

nearly 50,000 veterans are at risk of homelessness, and one in eight veterans between 2006

and 2008 were referred to counsellors for alcohol abuse.

When these costs are

combined, future medical

outlay for veterans of the Iraq

and Afghan missions are

estimated to be US$836.1

billion. In this context, the

benefits of solider-less

modes of operation to military

planners are clear.

Clear choice

From this, we can see how

the move towards drones is

driven by cost. The US in

particular is aware of the

danger of choosing guns

over butter, the economic

analogy where there is always

a trade-off between

investment in defence and

domestic prosperity. The US

used this to its advantage in

the Cold War when the Soviet

leadership leaned too heavily

towards guns by spending

around 25% of its budget on

defence in the early 1980s. As

a result, the domestic

economy collapsed and any

defensive gains from

increased spending were lost.

Americas adversaries are also acquainted with this economic tactic. Osama bin Laden and al-

Qaedas broader strategy was not to inflict damage to the US for the sake of damage itself.

Rather, terrorism was part of a larger strategy of bleeding America to the point of

bankruptcy.

At the same time, China has been careful not to engage the US in a game of defence

spending. It has been prudent in its expenditure, outlaying only 2.2% of its GDP on defence

compared to 4.4% for the US. It is also focusing on a steady, rather than rapid collection of

traditional defence tools, such as a blue water navy. This is because China is emphasising

modernisation using new technology rather than the old metric of simple platform numbers.

From this perspective, it seems US military planners have realised the perils of overspending.

Drones are viewed as the remedy. Whether this contributes to or harms international stability

is yet to be seen.

Soldiers are now more likely to survive catastrophic

battleground injuries than in the past. US Air Force/Staff Sgt.

Bennie J. Davis III

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- BR186 - Design Pr¡nciples For Smoke Ventilation in Enclosed Shopping CentresDokument40 SeitenBR186 - Design Pr¡nciples For Smoke Ventilation in Enclosed Shopping CentresTrung VanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume ObjectiveDokument2 SeitenResume Objectiveapi-12705072Noch keine Bewertungen

- Midterm Quiz 1 March 9.2021 QDokument5 SeitenMidterm Quiz 1 March 9.2021 QThalia RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Media Engagement and Feedback CycleDokument10 SeitenSocial Media Engagement and Feedback Cyclerichard martinNoch keine Bewertungen

- UntitledDokument1 SeiteUntitledsai gamingNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Sm15 Inppt 06Dokument57 SeitenDavid Sm15 Inppt 06Halima SyedNoch keine Bewertungen

- July2020 Month Transaction Summary PDFDokument4 SeitenJuly2020 Month Transaction Summary PDFJason GaskillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 1 Notes (Tabulation)Dokument5 SeitenUnit 1 Notes (Tabulation)RekhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Editing For BeginnersDokument43 SeitenEditing For BeginnersFriktNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comprehensive Accounting Cycle Review ProblemDokument11 SeitenComprehensive Accounting Cycle Review Problemapi-253984155Noch keine Bewertungen

- Student ManualDokument19 SeitenStudent ManualCarl Jay TenajerosNoch keine Bewertungen

- VM PDFDokument4 SeitenVM PDFTembre Rueda RaúlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Behaviour Models in Hospitality and TourismDokument16 SeitenConsumer Behaviour Models in Hospitality and Tourismfelize padllaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report - Fostering The Railway Sector Through The European Green Deal PDFDokument43 SeitenReport - Fostering The Railway Sector Through The European Green Deal PDFÁdámHegyiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cassava Starch Granule Structure-Function Properties - Influence of Time and Conditions at Harvest On Four Cultivars of Cassava StarchDokument10 SeitenCassava Starch Granule Structure-Function Properties - Influence of Time and Conditions at Harvest On Four Cultivars of Cassava Starchwahyuthp43Noch keine Bewertungen

- Questions - Mechanical Engineering Principle Lecture and Tutorial - Covering Basics On Distance, Velocity, Time, Pendulum, Hydrostatic Pressure, Fluids, Solids, EtcDokument8 SeitenQuestions - Mechanical Engineering Principle Lecture and Tutorial - Covering Basics On Distance, Velocity, Time, Pendulum, Hydrostatic Pressure, Fluids, Solids, EtcshanecarlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argus Technologies: Innovative Antenna SolutionsDokument21 SeitenArgus Technologies: Innovative Antenna SolutionsРуслан МарчевNoch keine Bewertungen

- HDMI CABLES PERFORMANCE EVALUATION & TESTING REPORT #1 - 50FT 15M+ LENGTH CABLES v3 SMLDokument11 SeitenHDMI CABLES PERFORMANCE EVALUATION & TESTING REPORT #1 - 50FT 15M+ LENGTH CABLES v3 SMLxojerax814Noch keine Bewertungen

- Salumber ProjectDokument103 SeitenSalumber ProjectVandhana RajasekaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slope Stability Analysis Using FlacDokument17 SeitenSlope Stability Analysis Using FlacSudarshan Barole100% (1)

- Np2 AnswerDokument13 SeitenNp2 AnswerMarie Jhoana100% (1)

- 0601 FortecstarDokument3 Seiten0601 FortecstarAlexander WieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMAZONS StategiesDokument2 SeitenAMAZONS StategiesPrachi VermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- QuartzDokument5 SeitenQuartzKannaTaniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hand Planer PDFDokument8 SeitenHand Planer PDFJelaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smart Meter Are HarmfulDokument165 SeitenSmart Meter Are HarmfulknownpersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Title IX - Crimes Against Personal Liberty and SecurityDokument49 SeitenTitle IX - Crimes Against Personal Liberty and SecuritymauiwawieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boeing 247 NotesDokument5 SeitenBoeing 247 Notesalbloi100% (1)

- NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMPANY v. CADokument11 SeitenNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMPANY v. CAAndrei Anne PalomarNoch keine Bewertungen

- DRPL Data Record Output SDP Version 4.17Dokument143 SeitenDRPL Data Record Output SDP Version 4.17rickebvNoch keine Bewertungen