Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

How The Arts Impact Communities

Hochgeladen von

Mehdi FaizyOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

How The Arts Impact Communities

Hochgeladen von

Mehdi FaizyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Working Paper Series, 20

!"# %&' ()%* +,-./% 0",,123%3'*4

An introduction to the literature on arts impact studies

Prepared by

Joshua Guetzkow

or the

5.6327 %&' 8'.*1)' "9 01:%1)' 0"29')'2/'

Princeton Uniersity

June -8, 2002

1he author thanks Paul DiMaggio and Stee 1epper or their guidance and suggestions, and

Jesse Mintz-Roth or his ine research assistance. Also, thanks are due to the Rockeeller loundation

or its generous support o this project. Please do not cite without permission. Direct any comments

or the author to joshgprinceton.edu.

+;5<=>?05+=;

As priate and public agencies seek innoatie ways to employ the arts to

improe and strengthen communities, they hae become increasingly interested in

assessing the impact o their inestments. In this context, arts adocates and

researchers hae made a ariety o ambitious claims about how the arts impact

communities. 1hese claims, howeer, are made problematic by the many

complications inoled in studying the arts. Just consider the possible deinitions o

the phrase, the arts impact communities.` \hen speaking o the arts,` do we reer

to indiidual participation ,as audience member or direct inolement,, to the

presence o arts organizations ,non-proit !"# or-proit, or to art,cultural districts,

estials or community arts \hen speaking o impact,` do we reer to economic,

cultural or social impact, do we reer exclusiely to direct community-leel eects or

do we also include indiidual- and organizational-leel ones By communities,` do

we mean regions, cities, neighborhoods, schools or ethnic groups

O course, there are no authoritatie answers to these questions, since

dierent research questions require dierent deinitions. And as one might expect,

arts impact studies employ these heterogeneous deinitions in a ariety o

combinations. Gien this array o deinitions, how would we go about measuring the

impact o the arts on communities One problem is that researchers and arts

adocates rarely seem to consider such complications when making claims about the

broader impact o the arts, and seldom discuss the implications o making particular

theoretical and methodological choices.

1

In this paper, I will lay out some o the issues that need to be addressed when

thinking about and studying how the arts impact communities, in addition to

proiding an introduction to the literature on arts impact studies. I begin discussing

the mechanisms through which the arts are said to hae an impact. lollowing this is a

1

To be Iair, many studies are not intended to examine the impact oI arts programs on the broader

community, but only at a relatively limited number oI participants. Nevertheless, the Iindings oI these

studies are oIten used by arts advocates to support more ambitious claims about the impact oI the arts on

communities.

1

discussion o key theoretical and methodological issues inoled in studying the

impact o the arts. I conclude by suggesting areas or urther research and relecting

on the limitations o past research.

8@0!(;+A8A

1he arts hae been heralded as a panacea or all kinds o problems Arts-

integrated school curricula supposedly improe academic perormance and student

discipline ,liske 1999, Remer 1990,. 1he arts reitalize neighborhoods and promote

economic prosperity ,Costello 1998, SCDCAC 2001, Stanziola 1999, \alesh 2001,.

Participation in the arts improes physical and psychological well-being ,Baklien

2000, Ball and Keating 2002, Bygren, Konlaan and Johansson 1996, 1urner and

Senior 2000,. 1he arts proide a catalyst or the creation o social capital and the

attainment o important community goals ,Goss 2000, Matarasso 199, \illiams

1995,.

Gien these claims, the question arises o how to elaborate the causal

mechanisms through which the arts hae an impact ,i.e., the interening actors that

connect a particular arts actiity with a speciic outcome,. Below is a grid that lays out

two dimensions that will help in thinking about this.

2

1he rows represent three

aspects o the arts typically highlighted in the literature: direct inolement in arts

organizations, especially that which entails personal engagement in some orm o

creatie actiity ,most oten associated with community arts programs and the use o

the arts in education,, participation in the arts as an audience member ,mostly

associated with cognitie ability, cultural capital and health improement arguments,

as well as economic impact studies o the arts - i.e., whether the arts hae an

economic impact by drawing audience dollars rom outside the community,, and the

presence o arts organizations in a community ,mostly associated with economic

impact studies and social capital arguments,.

2

This grid expands and builds upon a typology oI arts eIIects developed in a research proposal to the

Wallace-Readers Digest Funds by Kevin McCarthy (2002) oI the RAND Corporation.

2

5.B:' C4 8'/&.23*,* "9 ()%* +,-./%

`

Individual Community

Material/

Health

Cognitive /

Psych.

Interpersonal Economic Cultural Social

D

i

r

e

c

t

I

n

v

o

l

v

e

m

e

n

t

Builds inter-

personal ties and

promotes

volunteering,

which improves

health

Increases

opportunities Ior

selI-expression

and enjoyment

Reduces

delinquency in

high-risk youth

Increases sense oI

individual eIIicacy

and selI-esteem

Improves

individuals` sense

oI belonging or

attachment to a

community

Improves human

capital: skills and

creative abilities

Builds individual

social networks

Enhances ability

to work with

others and

communicate

ideas

Wages to paid

employees

Increases sense

oI collective

identity and

eIIicacy

Builds social

capital by getting

people involved,

by connecting

organizations to

each other and by

giving participants

experience in

organizing and

working with local

government and

nonproIits.

A

u

d

i

e

n

c

e

P

a

r

t

i

c

i

p

a

t

i

o

n

Increases

opportunities Ior

enjoyment

Relieves Stress

Increases cultural

capital

Enhances visuo-

spatial reasoning

(Mozart eIIect)

Improves school

perIormance

Increases tolerance

oI others

People (esp.

tourists/visitors)

spend money on

attending the arts

and on local

businesses. Further,

local spending by

these arts venues

and patronized

businesses has

indirect multiplier

eIIects

Builds

community

identity and pride

Leads to positive

commuunity

norms, such as

diversity,

tolerance and

Iree expression.

People come

together who

might not

otherwise come

into contact with

each other

P

r

e

s

e

n

c

e

o

f

A

r

t

i

s

t

s

a

n

d

A

r

t

s

O

r

g

a

n

i

z

a

t

i

o

n

&

I

n

s

t

i

t

u

t

i

o

n

s

Increases

individual

opportunity and

propensity to be

involved in the

arts

Increases prop-

ensity oI comm.-

unity members to

participate in the

arts

Increases attract-

tiveness oI area to

tourists, businesses,

people (esp. high-

skill workers) and

investments

Fosters a 'creative

milieu that spurs

economic growth in

creative industries.

Greater likelihood

oI revitalization

Improves

community

image and status

Promotes

neighborhood

cultural diversity

Reduces

neighborhood

crime and

delinquency

* This grid Iurther develops a typology proposed by Kevin McCarthy (2002).

3

1he columns represent types o impact and are diided into indiidual and

community leels. Indiidual-leel eects are releant or the purposes o community

impact studies to the extent that the impact o the arts on indiiduals aggregates to

the community. ,lor example, some indiidual-leel impacts, such as personal

enjoyment,` may not hae any consequences on community lie., 1he three types o

indiidual impacts are material ,mainly health,, cognitie,psychological and

interpersonal. 1ypes o community-leel eects, which are roughly homologous to

indiidual-leel ones, are economic, cultural and social. 1he cells o the table contain,

where releant, speciic impacts claimed in the literature.

1he grid helps to assess how dierent leels and types o artistic inputs are

related to dierent types o outputs. It can be taken as axiomatic that, other things

being equal, the more %&#'()*'!# and,or &"+'"(' the participation o community

members ,who are not inoled as proessionals,, the greater the impact the arts will

hae on cultural and social actors.

3

loweer, direct inolement is more intense

than audience participation, whereas audience participation is more widespread than

direct inolement. ,1o the extent that community arts programs are geared towards

producing some kind o public show` |art show, play, reading, estial, etc.|, they will

tend to optimize both dimensions o participation., Greater concentrations o artists

and arts-related organizations lead to higher degrees o arts participation among

residents, directly and as audience members ,Stern and Seiert 2000,. 1here is also

oten a trade-o between dierent types o arts actiities in terms o the kinds o

beneits they are most likely to produce. lor example, a well-respected theater

employing a proessional sta is more likely to draw isitors and tourists rom

outside the community than is a local community arts project exhibition, and hence it

will hae a greater economic impact. But, since the leel o participation among

community members lacks intensity in the case o the theater, it has less potential or

3

Note that this does not apply to economic impacts, since those rely primarily on bringing revenue Irom

outside the community. In this example, the type oI participation is widespread` and the degree is the

intensity.`

4

building social capital and a sense o collectie eicacy. Both the theater and the

community arts project may enhance community pride and sel-image.

It should be noted that, with the exception o economic impact studies,

almost all other research ocuses on the beneits that accrue to indiiduals and

organizations inoled in the arts, rather than the direct impact o the arts on a

community as such.

4

I will discuss this problem o aggregation later in the paper, but

or now I bracket it in aor o explicating mechanisms that connect well-deined arts

actiities to well-deined outcomes.

5

1he ollowing discussion is organized by claims

about the impact o the arts. I ocus on three types o claims: irst, claims that the arts

build social capital, second, claims that the arts improe the economy, and third,

claims that the arts are good or indiiduals. 1hese three broad claims capture

irtually all o the more speciic assertions about the impact o the arts.

0:.3,4 5&' .)%* 32/)'.*' *"/3.: /.-3%.:

6

.2D /",,123%E /"&'*3"2

Claims under this heading encompass the last two columns o the table -

community-leel cultural and social impacts - as well as interpersonal eects.

Virtually all studies that make this claim examine the eects o community arts

programs on the participants and organizations inoled ,Costello 1998, Dolan 1995,

Dreeszen 1992, lritschner and loman 1984, CDA 2000, Krieger 2001, Landry et

al. 1996, Matarasso 199, Matzke 2000, Murphy 1995, Ogilie 2000, Preston 1983,

Stern et al. 1994, Stern and Seiert 2002, 1rent 2000, \illiams 1995, \ollheim 2000,.

1he ollowing discussion draws on all o these studies.

Although quite aried, community arts programs are grassroots organizations

that attempt to use the arts as a tool or human or material deelopment ,Costello

1998,. Community arts programs almost uniersally inole community members in a

4

One notable exception is Stern (1999; 2001), who demonstrates that a greater concentration oI arts

organizations in a neighborhood leads to longer-lasting ethnic and economic diversity in that neighborhood.

5

By aggregation, I reIer to the process by which eIIects on individuals, taken together, can combine to have

an inIluence on the broader community.

6

Scholars oIten Iail to deIine precisely what they mean by social capital. According to Robert Putnam`s

inIluential deIinition, 'social capital reIers to connections among individuals social networks and the

norms oI reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise Irom them, which may Iacilitate coordination and

cooperation Ior mutual beneIit (2001: 19)

5

creatie actiity leading to a public perormance or exhibit. As deined by the Ontario

Arts Council ,2002,, Community Arts is an art process that inoles proessional

artists and community members in a collaboratie creatie process resulting in

collectie experience and public expression. It proides a way or communities to

express themseles, enables artists, through inancial or other supports, to engage in

creatie actiity with communities, and is collaboratie - the creatie process is

equally important as the artistic outcome.` ,Note that this is dierent rom such

things as local, neighborhood knitting groups., Community arts programs oten

inole people who are disadantaged in some way ,at-risk youth, ethnic minorities,

people in a poor neighborhood, and are designed in the context o some larger goal,

such as neighborhood improement ,typically aesthetic, or learning and teaching

about dierse cultures ,multiculturalism,. 1hese goals are usually the basis or claims

about the politically transormatie potential o community arts projects ,e.g., see

\illiams 199,. Regardless o the ultimate purpose,s, to which social capital is to be

put, community arts programs are said to build social capital by boosting indiiduals`

ability and motiation to be ciically engaged, as well as building organizational

capacity or eectie action. 1his is speciically accomplished by:

Creating a enue that draws people together who would otherwise not be

engaged in constructie social actiity.

lostering trust between participants and thereby increasing their

generalized trust o others

Proiding an experience o collectie eicacy and ciic engagement, which

spurs participants to urther collectie action

Arts eents may be a source o pride or residents ,participants and non-

participants alike, in their community, increasing their sense o connection

to that community.

Proiding an experience or participants to learn technical and

interpersonal skills important or collectie organizing

Increasing the scope o indiiduals` social networks

6

Proiding an experience or the organizations inoled to enhance their

capacities. Much o this comes when organizations` establish ties and learn

how to work, consult and coordinate with other organizations and

goernment bodies in order to accomplish their goals.

A case study rom \illiams` ,1995: 101-106,, research in Australia proides an

example o these mechanisms. 1he study was conducted on a sample o recipients o

community-based arts grants proided by the Australia Council. One o these grants

was gien to a small group o women residents o Longlea, a suburb o Brisbane.

1heir goal was to beautiy their blighted community center, which inoled local

residents in the creation o artworks around the community center. 1his drew

together townspeople who might otherwise hae stayed at home to engage in a

constructie social actiity. As people worked collaboratiely on the project and got

to know each other better, their mutual trust increased. 1heir success in negotiating

with the municipal bureaucracy in order to accomplish the task gae participants a

newound sense that they could accomplish other goals. 1he community group and

indiiduals coordinating the eorts learned organizing skills, learned how to naigate

the bureaucracy and built relationships with the municipal and regional goernment.

linally, the people inoled elt an increased sense o pride and appreciation o their

town.

0:.3,4 5&' .)%* &.F' . B'2'93/3.: 3,-./% "2 %&' '/"2",E

Lconomic impacts are perhaps the most widely touted beneits o the arts.

1he literature on economic impact studies o the arts tends to all into two categories:

on the one hand, adocacy studies based on quick appraisals that oten exaggerate the

impact o the arts ,Azmier 2002, Bryan 1998, Lckstein 1995, Perryman 2001,

SCDCAC 2001, Singer 2000, \alesh 2001,. On the other hand are more rigorous

studies -- which, oertime, show increasing methodological reinement ,Cohen 1994,

Costello 1998, CPC 2002, Cwi 1980a, Cwi 1980b, Cwi and Lyall 19, DiNoto and

Merk 1993, lrey 1998, Gazel 199, Kling, Reier and Sable 2001, Mitchell 1993,

7

O'lagan and Duy 198, Port Authority o New \ork and New Jersey 1983, Radich

198, Rolph 2001, Sable and Kling 2001, Seaman 199, Stern and Seiert 2000,

1hrosby 2001, 1raers, Stokes and Kleinmann 199,. In the ollowing discussion, I

hae tried to rely on these more rigorous studies.

1he arts attract isitors ,art as export` industry,:

1ourists isit a community primarily in order to attend an arts eent

,alternatiely, tourists may prolong a trip in order to attend an arts

eent,. 1hey will spend directly on the arts eent and may also shop,

eat at a local restaurant and,or stay at a hotel in the community. 1o the

extent that these tourist dollars are spent by the arts organization - as

well as the stores, restaurants and hotels - on local goods and serices,

the dollars brought in to the community or an arts eent will hae

indirect multiplier eects on the local economy.

1he arts attract residents and businesses:

1he density o arts organizations and prealence o arts eents may

play a role in attracting residents and businesses to ,re,locate to a

community by improing its image and making it more appealing. 1his

is especially true or attracting highly skilled, high-wage residents, who

will hae a larger economic impact than less-skilled people. Businesses,

especially those that employ highly trained mobile personnel, may

consider the presence o art enues when making ,re,location decisions

,Cwi 1980b: 18-19,. 1he presence o the arts ,i.e., improed image o

an area, may work to enhance the impact o tax incenties or business

location decisions ,Costello 1998: 14-9,.

ligh concentrations o artists and,or high-skilled workers may

produce agglomeration eects, where businesses ,especially those in

the ast-growing creatie industries` ,\alesh 2001,, are drawn to an

area because o the aailability o creatie talent and,or high-skilled

workers, and ice ersa.

1he arts attract inestments:

By improing a community`s image, people may eel more conident

about inesting in that community. So or example, people might be

7

An indirect multiplier is based on the idea that a portion oI each dollar spent on some good or service is

then used by the recipient to pay Ior more goods and services. To the extent that the money circulates

within a community (e.g., a city), it multiplies` within that community. So Ior example, iI you spend $20

on a ticket to a play, the playhouse turns around and spends $15 oI that Ior set design supplies Irom local

markets. The employees also spend locally some portion oI their income that is derived Irom that $15 to

pay Ior more goods and services; and the stores Irom which they bought supplies in turn use some oI that

money to pay their workers and buy more supplies, and so on. This multiplies` the value oI the initial $20.

8

more likely to buy property in an area that they eel is up-and-

coming` because o the presence o the arts. Or, banks may be more

likely to lend to businesses in areas perceied as more secure and

stable, and so on.

One problem with determining the impact o the arts is distinguishing

between reenue rom locals s. reenue rom tourists, and among the latter

determining the extent to which the arts drew them to isit the community.

Lxpenditures by locals should not be included in studies o the economic impact o

the arts, because the arts may simply represent an alternatie outlet or spending

,rather than an additional outlet,, thus representing no net dierences on the local

economy ,assuming equal multiplier eects among outlets,. In terms o priate and

public subsidies or the arts, it is diicult to determine the opportunity costs o

inesting the money in other things ,i.e., whether inesting the same amount o

money in something else would hae a stronger impact on the economy,. 1here is

scant eidence on whether money spent on the arts is more likely to circulate locally

than money spent in other areas ,though see Palmer 2002 or a comparison o arts

perormances ersus sports arenas,.

As an example o how the arts may hae an economic impact, let us examine a

summer theater estial that a small town puts on eery year,Mitchell 1993,. 1his

estial draws thousands o isitors who come - some rom ar away, but most rom

the surrounding area - in order to attend the perormance. 1hese isitors spend

money on tickets as well as restaurants, hotels, parking and retail shopping. ,In this

sense, the arts are said to be an export` industry to the extent that they bring in

money rom outside the local economy., 1his spending has a direct positie impact

on the town`s economy. Indirectly, this spending has what is called a multiplier

eect` to the extent that those dollars re-circulate in the local economy as a result o

spending on local goods and serices by the estial and the other business.

9

0:.3,4 5&' .)%* .)' 7""D 9") 32D3F3D1.:*

Claims that the arts are good or indiiduals take many orms. 1he arts hae

been said to improe health, mental well-being, cognitie unctioning, creatie ability

and academic perormance.

1he arts improe indiidual health.

Lither engaging in creatie actiity or simply attending some kind o

artistic eent appears to improe physical health ,Angus 1999, Baklien

2000, Ball and Keating 2002, Bygren, Konlaan and Johansson 1996,

lDA 2000, 1hoits and lewitt 2001,. 1his could be due in part to its

ability to reliee stress. Also, arts engagement widens and strengthens

social bonds, which also improes health ,Baklien 2000: 250-51, Ball

and Keating 2002,. On a more physiological leel, Bygren, Konlaan

and Johansson ,1996: 1580, explain: we know that the organism

responds with changes in the humoral nerous system--or example,

erbal expression o traumatic experiences through writing or talking

improes physical health, enhances immune unction, and is associated

with ewer medical isits.`

1he arts improe psychological well-being.

lere we hae to distinguish between passie and actie participation.

Attending arts eents may be stimulating and reliee stress, hence

leading to improed happiness, lie satisaction. Actie participation in

the arts leads, in addition, to improed sel-concept and sense o

control oer one`s lie. 1here are dierent reasons why this might be

so. Lots o the anecdotal eidence comes rom community arts

programs, some o which are geared towards poor, marginal or at-risk`

populations ,Lynch and Chosa 1996, Seham 199, \eitz 1996,

\illiams 1995,. 1his is backed up by the little - and poor quality -

surey data that do exist. 1o the extent that the creation and

completion o some arts project proides an opportunity to such

participants to succeed and gain some positie public recognition, it

will improe their sense o control oer their lie and sel-concept

,liske 1999, Jackson 199, Randall, Magie and Miller 199, Seham

199, \eitz 1996,. 1o date, there has been no systematic comparison

between community arts programs operating in dierent socio-

economic climates to see whether such eects appear to be uniorm.

1he arts improe skills, cultural capital and creatiity.

lere again we hae to distinguish between passie and actie

participation. Audience members may gain some new knowledge or

10

cultural capital

8

by attending arts eents. 1here is also the so-called

Mozart eect showing that children who listen to Mozart ,and other

similar stimuli, show improed perormance on isuo-spatial reasoning

tests - although the eect may not last ,Chabris et al. 1999, letland

2000,. Indiiduals directly inoled in creating or organizing artistic

actiity may learn skills that they did not preiously hae and may

demonstrate greater creatiity ,liske 1999, Randall, Magie and Miller

199, Rolph 2001, Seham 199, Sharp 2001, \eitz 1996,. On the

whole, education studies show that kids engaged in an arts class will do

better in other subjects and that an arts-integrated curriculum improes

school perormance ,Albert 1995, liske 1999, Jackson 199, Remer

1990, \eitz 1996, \inner and letland 2000,. 1he basic reason or

this may be that children ind learning through artistic,creatie actiity

much more enjoyable, and so they will hae an easier time engaging

with the material. It is important to point out, howeer, that most

studies do not control suiciently or sel-selection into arts actiities

and the eects are not as dramatic as boosters would claim.

1he ,-.&"/ 0) 1!22'* report ,\eitz 1996, proides concrete examples o some

o these mechanisms. 1he report identiies arts-training programs targeted at at-risk

youth and seeks to understand why these programs work. At least two o the

programs inoled working with sentenced juenile oenders. One program taught

musical theater, the other painting. Both programs appeared to enhance the sel-

esteem o their participants, because they learned new skills, ound that they had

undiscoered talents, and receied positie recognition rom peers and others when

they perorm or exhibit their work. Learning new skills may also improe their

position on the job market. lor example, in addition to learning singing, dancing and

acting, participants in the music theater program also learn about the technical side o

producing a play, such as lighting, set-design and sound. Also, perorming a play or

doing other kinds o artistic actiity can proide a means o learning that children

ind much more un and engaging. As a result they will learn and absorb the material

better.

8

I use the most restricted deIinition oI cultural capital as simply knowledge oI the Iine arts. For example, in

taking an arts class, one learns something about aesthetics and art appreciation and perhaps about art

history. Such knowledge has been linked to better school perIormance and improvement oI other liIe

outcomes (DiMaggio 1982; DiMaggio and Mohr 1985).

11

5!@=<@5+0(G H 8@5!=>=G=I+0(G +AA?@A

>'9323%3"2*

As I pointed out at the start, the phrase arts impact communities` admits o

many possible deinitions. Speciying these deinitions is an important task that

researchers oten ignore. lere, I briely sketch some dimensions along which these

terms can be deined.

3'4&"&"/ 5+6' !*+(7 - Dierent research projects rarely deine the arts` in the

same way, and oten the same study will include dierse actiities and organizations,

including proessional opera companies, neighborhood cultural centers, community

arts programs and in some cases een major league sports. 1here are seeral

dimensions along which deinitions o the arts might be speciied: genre or art-orm

,whether the actiity is painting, singing, acting, etc.,, sector ,whether the

organization inoled is non-proit, commercial or goernmental,, time ,duration o

the arts actiity or inolement,, place ,where does the actiity,perormance take

place,, group participation ,whether the actiity is done alone, in small groups or in

large groups,, medium ,whether the arts is lie, recorded or \eb-based,, and mode o

participation ,whether inolement is actie art-making, organizational olunteering

or audience participation,.

1his last dimension proides a distinction useul or classiying prior studies.

Some studies look at the eect o participation in the arts on those who are directly

inoled, especially when they are engaged in art-making. Such studies oten examine

the impact o community arts programs ,CDA 2000, Landry et al. 1996, Matarasso

199, Matzke 2000, Murphy 1995, 1rent 2000, \illiams 1995, \ollheim 2000, or

arts-centered teaching programs ,Albert 1995, liske 1999, Jackson 199, Remer 1990,

Seham 199, Sharp 2001, \eitz 1996, \inner and letland 2000,, usually on the

participants themseles but sometimes on the local community. Other studies look at

arts attendance, occasionally examining the impact o the arts on their audience

,Bygren, Konlaan and Johansson 1996, Chabris et al. 1999, letland 2000, Landry et

12

al. 1996, Matarasso 1999, \illiams 1995,, but most oten ocusing on the audience`s

impact on the local economy ,Bendixen 199, DiMaggio, Useem and Brown 198,

lrey 1998, Gazel 199, Laing and \ork 2000, Mitchell 1993, O'lagan and Duy

198, SA1C 1998,.

9

A third major ocus o arts research is on the presence and

density o arts organizations, looking sometimes at how these actors aect

inolement in the arts and other local organizations ,Stern 1999, Stern and Seiert

2000,, but typically emphasizing the impact o arts organizations on the local

economy ,Cohen 1994, Costello 1998, Cwi 1980a, DiNoto and Merk 1993, Port

Authority o New \ork and New Jersey 1983, Stern 2001, Stern and Seiert 2000,

1raers, Stokes and Kleinmann 199,. lere I hae simply proided a quick surey o

the deinitional terrain o arts studies. 1he broader point to be made is simply that it

is crucial to deine precisely what are the arts` that one is studying, because dierent

arts actiities are likely to lead to a dierent set o outcomes. lurthermore, the use o

ague and dierse deinitions o the arts` makes comparability and accumulation

across studies ery diicult.

3'4&"&"/ 5&.)!8+7 -- As this discussion illustrates, deining the scope o what is

meant by the arts` goes some length towards delimiting their potential impact. ,lor

example, a school arts program is not likely to hae an appreciable impact on the

economy o a city., Like the arts, there are also a number o dimensions along which

the scope o the impact,s, ought to be clariied: whether the impact is on indiiduals,

institutions,organizations, communities or the economy, whether it is direct or

indirect ,e.g., does it indirectly aect communities by aecting indiiduals,, whether

the impact is short-term or long-term, whether impacts are greater or some groups

and indiiduals than or others, and whether the impact is social, cultural,

psychological, economic, and so on. 1hese dimensions are oten under-speciied, and

as a result indings can be easily inlated or oer generalized ,e.g., a small, short-term

impact on a subgroup o people might be iewed as an enduring impact on a broader

9

Dollars spent in a community by cultural tourists are only one way in which the arts are said to have an

economic impact.

13

class o residents,. lurthermore, as Cwi ,198, notes, the policy releance o most

arts program ealuations studies is limited, because o their ailure to adequately

speciy the impact that the program is intended to hae.

3'4&"&"/ 58-..9"&+:7 - Community can be deined in a ariety o ways: as a

geographic region, municipality, neighborhood ,itsel open to a ariety o deinitions,,

or ethnic group. In general, researchers use one o two criteria in deining

community: propinquity and group membership. \ith the irst criterion, researchers

deine community in terms o people`s proximity to one another and study things like

neighborhoods, schools, cities or SMSAs. lor example, the Social Impact o the Arts

Project ,SIAP, usually uses census block groups` as part o its deinition o

neighborhood, and also historically institutionalized, widely recognized

neighborhoods, such as Germantown in Philadelphia or the south side` o Chicago

,Stern 2001,. Another common way to deine community is as a legally distinct area,

such as a town, city or state ,Cwi 1980a, Cwi 1982, Cwi and Lyall 19, DiNoto and

Merk 1993, Gazel 199, Mitchell 1993, NALAA 1994, Perryman 2001,. Studies using

this criterion usually ocus on the economic impact o the arts, so examining a well-

deined tax base makes sense. Alternatiely, researchers may study community

deined by group membership, categorizing people on the basis o race,ethnicity,

national origin, gender, sexual orientation, occupation and so orth.

Researchers may use one o two methods or classiying people into

communities: one method deines community on the basis o criteria imposed by the

researcher, the other deines community in accord with indiiduals` sel-identiication

,see Stern et al. 1994 or an example o this,. Note that the basis o people`s sel-

identiication can come rom many sources. It may be coterminous with proximity-

or legally-based deinitions ,e.g., I`m rom Germantown,` I`m rom Robert 1aylor

lomes` or I`m rom Atlanta,.` People may also sel-identiy on the basis o group

membership. Some community-based arts programs are organized around such

communities. lor example, one program studied by \illiams ,1995, was designed to

hae aboriginal children in a rural Australian town express their culture. It is

14

important to distinguish between researcher-imposed s. sel-identiied deinitions o

community. It is possible, or example, that in order to understand i and how the

arts contribute to such subjectie outcomes as increased trust o others, greater pride

in one`s community and motiation to work towards collectie ends, then one needs

to take an inductie approach to this question o community ,e.g., using deinitions

that members themseles put orward,. And i there is a disjuncture between the

researcher`s deinition o a community and the sel-identiications o its members,

then the researcher may ail to ind eidence o, or example, social solidarity

,because s,he would be looking in the wrong places or eidence,.

10

\hether researcher-imposed or not, clearly speciying the scope o the

community is crucial when trying to think about how the arts impact a community

directly, as well as the related problem o aggregation.

5&' J)"B:', "9 (77)'7.%3"2

One o the more exing issues conronting anyone wishing to understand the

impact o the arts on communities is the question o how to link micro-leel eects

on indiiduals to the more macro leel o the community. Lxcept or economic

impact studies, irtually eery arts impact study examines how the arts aect

indiiduals ,though see Stern 1999, 2001,, whether by improing their health ,Bygren,

Konlaan and Johansson 1996, Costello 1998,, their sel-esteem ,\eitz 1996,, their

skills, talents and knowledge ,liske 1999, \inner and letland 2000,, or their

tolerance o other cultures ,Matarasso 199, \illiams 1995,. In some cases,

researchers hae also argued that the creation o arts programs ,usually made possible

by goernment or priate grants, increases the capacities o arts organizations, or

example by enhancing their ability to work with local goernment agencies ,Stern and

Seiert 2002, \illiams 199,. In this case, the problem becomes one o aggregating

organizations rather than indiiduals.

10

I am grateIul to Paul DiMaggio Ior suggesting these last two points.

15

Note that deining the scope o the community in question is critical to the

problem o aggregation. lor example, other things equal, a small community arts

program is more likely to hae an impact on people in the neighborhood in which it

operates than on people liing on the other side o town. But without haing to

deine community, at least ie general ways in which indiidual,organizational-leel

eects might aggregate can be distinguished:

1. Most obiously, one could simply talk in terms o the percentage o

indiiduals,organizations in a population that are aected. Social capital is

typically conceied o in such a manner, where a community with a higher

percentage o indiiduals participating in ciic groups and,or a greater density

o such groups is considered to hae greater social capital. lence, i arts

programs get more indiiduals inoled in community groups, then they

increase the community`s social capital.

2. Closely related to this is the idea that there may be threshold leels or tipping

points` ,Gladwell 2000, at which indiidual,organizational-leel eects begin

to hae community-leel consequences. In this case, as in number 1 aboe, an

unresoled issue is determining the leel at which these eects can properly be

said to hae an impact on the community.`

3. 1he presence o the arts and,or participation by community members may

hae an impact on community norms or the opinion climate.` lor example,

the presences and perormances o a multicultural theater may reinorce

norms about multiculturalism and diersity or ree expression..

4. 1o the extent that arts organizations sere as a catalyst in the creation o ties

between dispersed indiiduals and organizations ,who would not otherwise

establish ties,, these networks, may then be used to accomplish other

community goals.

5. Communities may be aected when a ew key indiiduals and,or

organizations are aected. lor example, a successul community arts program

may inluence the perceptions o key goernment oicials and make them

16

more likely to support such programs in the uture. Or successul arts-based

neighborhood reitalization programs targeted at particular crime-ridden

neighborhoods or juenile oenders may lower the oerall crime rate.

6. linally, indiiduals and groups inoled in the arts can be said to aect the

community by creating public goods.

11

1he alue o arts as a public good ,its

contingent aluation, is usually measured by willingness-to-pay sureys

12

,CPC

2002, Kling, Reier and Sable 2001, Sable and Kling 2001, Seaman 199,

1hrosby 2001,.

A':'/%3"2 J)"B:',*

As with much social research, arts impact studies typically suer rom

selection bias problems, which make it diicult to identiy clearly the causal role o

the arts.

13

1his problem is usually expressed by the truism that correlation is not

causation.` lor example, research indicates that people who participate in the arts are

healthier and happier ,Bygren, Konlaan and Johansson 1996, Costello 1998, 1hoits

and lewitt 2001,. But, does this mean that arts inolement makes people healthier

and happier, or that such people are more likely to get inoled in the arts Do arts

programs build social capital, or are communities with higher social capital more

likely to initiate arts programs Usually, the answer to such questions is both.` On

aerage, healthier people are more likely to olunteer in arts programs, but that

actiity likely improes their health as well ,1hoits and lewitt 2001,. Communities

with greater social capital are more likely to initiate arts programs, but those programs

may urther promote the building o social capital. Most likely, health or social capital

11

Outdoor sculpture is a good example oI public goods, since many people can enjoy it. But, people don`t

necessarily need to use/enjoy art Ior it to be a public good.

12

Willingness-to-pay surveys ask respondents how much they would be willing to pay (usually in taxes) to

support some artistic activity (e.g., 'How much would you be willing to pay in taxes to support the

NEA?). People who don`t patronize the arts still report that they are willing to pay to Iund them, and this

is interpreted to mean that the arts are valuable to them.

13

Generically, selection bias means that the sample (i.e., the people and/or organizations that one is

studying) is not representative oI the entire population, leading to conclusions that are not valid. In arts

research, the most pernicious oI these is selI-selection bias: since people who choose participate in the arts

may be diIIerent Irom others, that diIIerence may explain the observed outcome rather than the arts

activity.

17

would not hae improed in the same way and to the same degree had the arts

programs been absent. \hen seen rom this perspectie, selection issues - when

recognized and handled appropriately - arguably do not present an intractable

problem to arts impact studies.

G./6 "9 (--)"-)3.%' 0",-.)3*"2*

lrom a policy perspectie, howeer, the issue is no longer whether the

existence o the arts has a beneicial impact, but whether money spent on arts

programs will hae .-*' o an impact than other programs. Indeed, one law with the

literature on arts impact is the lack o studies that compare the arts with other

programs or industries. 1he key question or policy-makers ,or grant-giers, is this:

gien some pre-deined goal ,improing the economy, attracting tourism, improing

education, reorming at-risk adolescents, etc.,, how can that goal be most eectiely

reached 1hus, the issue changes rom did this program work at all` to did this

program work better than another` Instead o what are the beneits o the arts,` the

question becomes what are the opportunity costs

14

o using this money to und the

arts` lor example, are arts programs or at-risk youth more eectie than the Boy

Scouts or midnight basketball Do arts programs draw people away rom other high-

impact actiities in which they would otherwise be inoled, such as enironmental

actiism or charity, would public money be better spent on things like transportation

inrastructure or police Determining whether a program is more eectie` than

another is o course no simple matter and demands precise deinition o the goal o

the program, but none o the studies I reiewed adequately addressed this issue. 1he

diiculty o the comparison is compounded by the act that many o the beneits we

associate with the arts, like increased creatiity or eelings o well-being, are

intangible` and thereore diicult to measure. loweer, to the extent that the arts do

potentially proide something unique, the lack o comparatie studies make it that

much more diicult to concretely demonstrate the unique contribution o the arts.

14

Opportunity costs basically mean that when you spend your money or time in one activity/investment,

there is a cost oI not being able to use that time or money in some other activity/investment.

18

;'7.%3F' @K%')2.:3%3'*

In addition to ignoring opportunity costs, arts impact studies typically ignore

the potentially negatie impacts o the arts. lor example, gien the broad deinition

o the arts` ound in many studies, the negatie impact o such eents as raes or

rock concerts - or example noise pollution and delinquency - largely goes ignored

,though see Gazel |199| or an economic impact study o a Grateul Dead concert in

Las Vegas that took into account the city`s extra expenditures on security or the

eent,. Or, i an arts` program builds social solidarity among some ethnic group,

could this lead to greater balkanization o the community Zukin`s ,1989, study o

New \ork City shows that the presence o arts actiities and artists in a poor

neighborhood may be a harbinger o gentriication ,though see Stern |1999| or

eidence rom other cities that the presence o arts organizations leads to lasting

diersity,. 1o the extent that studies do examine ailed programs, they tend to ocus

on the causes o ailure rather than its consequences ,Matarasso 199, \illiams 199,.

In short, those who inestigate the impact o the arts need to be more aware o

potential negatie as well as positie impacts.

G./6 "9 (D'L1.%' >.%.

Most arts impact studies are based on cross-sectional data, making inerences

about selection and the causal role o the arts exceedingly diicult. 1he lack o oer-

time data also makes it impossible to see how long the eects o an arts program

persist.

15

lurthermore, the sample sizes o many studies are too small or making

proper statistical inerences.

16

In many instances, researchers employ multiple or

comparatie case study approaches, or example by studying seeral dierent

community arts programs. Despite the strengths o this type o analysis or describing

15

Williams` (1997) study in Australia did Iollow some oI the communities she studied Ior several years

aIter the initial program; this enabled her to draw inIerences about what Iactors lead to sustained impact.

16

Statistical inIerences (Ior example, determining with what degree oI conIidence we can say that children

in arts programs do better in school) are based on the premise that the sample is representative oI the entire

population. The representativeness oI small sample sizes cannot be guaranteed with a high level oI

conIidence.

19

in detail the supposed consequences o particular arts programs on particular

indiiduals, these studies are limited in a number o ways:

lirst, they tend to rely exclusiely on the subjectie accounts o people

inoled in the art programs or audience members in order to support their claims -

in short, they tend to be anecdote-rich and eidence-poor ,though perhaps there`s an

argument to be made that a mountain o anecdotes seres as some kind o eidence,.

1he undamental question here is whether impact can be .'!(9*'# solely or largely on

the basis o these accounts, especially considering that participants almost always sel-

select into participation. \hat would happen i people were randomly assigned into

an arts treatment` group 1his is closely related to another problem with these, as

with other arts impact studies, which is that they tend to sample only treated groups.

lor example, questionnaires go only to people who are centrally or closely inoled

in a particular arts program, rarely asking community members what consequences

the program had on them ,though see Matarasso 199,. Also, ealuation studies only

look at organizations or communities that won the supporting grant ,whose impact

the study is intended to measure,, neer comparing it with a similar community that

didn`t win a grant, let alone one that neer een applied. No doubt it is especially

diicult to create a quasi-experimental design in applied social science, but arts

impact research seldom makes an eort to achiee this goal. ,One problem, o

course, has been lack o adequate unding to undertake such an eort., More

generically, the problem with in-depth case studies is that they are rarely

representatie o the oerall population.

A-'/393/.%3"2 "9 0"2%'K% @99'/%* .2D +2%')F'2327 M./%")*

Researchers studying the impact o the arts are rarely sensitie to contextual or

interening actors that inluence the outcomes they ind. 1his is important or

generalizing rom the indings o a speciic study. 1o take a simple example, many

studies claim that the arts hae a beneicial economic impact. loweer, it is likely

that this impact aries depending on the size o the community under discussion and

20

the size and density o arts organizations,eents. 1hus, in order or the arts to make

an appreciable ,and perhaps measurable, impact on the economy o a large city, it will

likely require the deelopment o an arts district ,such as the 1emple Bar in Dublin,

see Costello 1998,. An annual drama estial is likely to hae little economic impact

on a large city ,though it may hae an appreciable impact on the neighborhood in

which it is located,, but may be a decisie actor in the economy o a small town

,Mitchell 1993,. And local community arts projects are likely to hae little economic

impact. 1he National Association o Local Arts Agencies study is one o the best to

date in selecting arts actiities o arious sizes across a wide range o municipalities

,Cohen 1994,. 1he point is simply that arts impact researchers need to begin to think

more seriously about the conditions under which their results do - or do not -

generalize.

0=;0G?A+=;

Research on the how the arts impact communities is a burgeoning and wide-

ranging ield o research. Despite the ariety o research subjects and methodologies

alie and well in the ield, there are a number o aenues this literature has yet to

explore. lor example, researchers study ormal groups and organizations to the

exclusion o more inormal groups, such as local neighborhood knitting groups and

the like. Case studies tend to ocus on arts programs deeloped or marginal

populations ,like at-risk children,, it would be interesting to see what could be learned

rom comparing these programs to ones where most o the participants are middle-

or upper-middle class. Also, researchers oten study community arts programs that

hae some kind o political or social goal: what might be learned by comparing these

organizations to those that hae no such goal And in terms o determining their

relatie economic impact, we need to know whether arts organizations tend to spend

more money in the local economy and on locally-produced goods than do other

organizations,businesses. 1hese examples point to a larger problem with the research

in this ield, especially those that use multiple, in-depth case studies: the cases are

21

generally not chosen in such a way as to gain much empirical leerage` rom the

comparison. Cases appear to be selected on the basis o capturing the widest diersity

o programs possible - sometimes with an implication that this will ensure

representatieness. 1he most that comes rom this sort o comparison is a list o

some actors that appear to aect the relatie success o the programs. Researchers

need to think more about the logic driing their case selection, so that they can get

more rom their comparisons.

1he criticisms that I hae enumerated in this paper could apply to most bodies o

social research. But, the ield o cultural policy studies is young and resources are

scarce. 1hereore, it is perhaps more important than in other ields that small

inestments in research yield strong results that can be leeraged to adance public

policy and priate philanthropy. As a result, it is especially incumbent upon arts

researchers to careully speciy their deinitions and think critically about the

theoretical and empirical issues conronting them when attempting to take the

measure o culture.

22

<@M@<@;0@A

Albert, Maria. 1995. "Impact oI an arts-integrated social studies curriculum on eighth graders'

thinking capacities." Pp. xi, 344 leaves ; p., 29 cm. Lexington, Ky.: University oI

Kentucky.

Angus, John. 1999. An Enquirv concerning Possible Methods for evaluation Arts for Health

Profects. Bath, UK: Community Health.

Azmier, Jason J. 2002. "Culture and Economic Competitveness: An Emerging Role Ior the Arts

in Canada." Canada West Foundation.

Baklien, Bergljot. 2000. "Culture is Healthy." International Journal of Cultural Policv 7.

Ball, Susan, and Clare Keating. 2002. "Researching Ior Arts and Health's Sake." in 2nd

Conference on Cultural Policv Research. Wellington, NZ.

Bendixen, Petere. 1997. "Cultural Tourism - Economic Success at the Expense oI Culture?"

International Journal of Cultural Policv 4.

Bryan, Jane. 1998. The economic impact of the arts and cultural industries in Wales. CardiII:

|CardiII Business School?|.

Bygren, Lars O., Boinkum B. Konlaan, and Sven-Erik Johansson. 1996. "Attendance at cultural

events, reading books or periodicals, and making music or singing in a choir as

determinants Ior survival: Swedish interview survey oI living conditions." British

Medical Journal 313:1577-1580.

Chabris, Christopher F, Kenneth M Steele, Simone Dalla Bella, Isbelle Peretz, Tracy Dunlop,

Lloyd A Dawe, G Keith Humphrey, Roberta A Shannon, Johnny L Jr Kirby, CG

Olmstead, and Frances H Rauscher. 1999. "Prelude or requiem Ior the "Mozart EIIect"."

Nature 400:826-828.

Cohen, Randy. 1994. Arts in the local economv. final report. Washington: National Assembly oI

Local Arts Agencies.

Costello, Donal Joseph. 1998. "The Economic and Social Impact oI the Arts on Urban and

Community Development." Pp. 1333-A in Dissertation Abstracts International, A. The

Humanities and Social Sciences. Pittsburgh: University oI Pittsburgh.

CPC. 2002. "Contingent Valuation oI Culture ConIerence." Cultural Policy Center at the

University oI Chicago. http://culturalpolicy.uchicago.edu/cvmconI.html.

Cwi, David. 1980a. The economic impact of ten cultural institutions on the economv of the

Springfield, Illinois SMSA. SpringIield, Ill.: Center Ior the Study oI Middle-size Cities

Sangamon State University.

. 1980b. The role of the arts in urban economic development. Washington, D.C.: Economic

Research Division Economic Development Administration.

. 1982. The arts in New Jersev . status, impacts, needs. Trenton, N.J.: The Council.

Cwi, David, and Katharine Lyall. 1977. A model to assess the local economic impact of arts

institutions . the Baltimore case studv. Baltimore: Center Ior Metropolitan Planning and

Research the Johns Hopkins Univ.

DiMaggio, Paul. 1982. "Cultural Capital and School Success: The Impact oI Status Culture

Participation on the Grades oI U.S. High School Students." American Journal of

Sociologv 47:189-201.

DiMaggio, Paul, and John Mohr. 1985. "Cultural Capital, Educational Attainment, and Marital

Selection." American Journal of Sociologv 90:1231-1261.

DiMaggio, Paul, Michael Useem, and Paula Brown. 1978. "Audience Studies oI the PerIorming

Arts and Museums: A Critical Review." Research Division, The National Endowment Ior

the Arts.

DiNoto, Michael J, and Lawrence H Merk. 1993. "Small Economy Estimates oI the Impact oI the

Arts." Journal of Cultural Economics 17:41-54.

23

Dolan, Teresa. 1995. Communitv Arts. Helping to Build Communities? Taken from a Southern

Ireland perspective. London: City University.

Dreeszen, Craig. 1992. "Intersections: Community Arts and Education Collaborations." Journal

of Arts, Management, Law and Societv 22:211-240.

Eckstein, Jeremy. 1995. The Contribution of the Cultural Sector to the UK economv. London:

Policy Studies Institute.

Fiske, Edward B. 1999. Champions of change . the impact of the arts on learning. Washington,

DC: Arts Education Partnership President's Committee on the Arts and the Humanities.

Frey, Bruno S. 1998. "Superstar Museums: An Economic Analysis." Journal of Cultural

Economics 22:113-25.

Fritschner, Linda Marie, and Miles K. HoIIman. 1984. "The Community and the Local Art

Center." in American Sociological Association.

Gazel, Ricardo. 1997. "Beyond Rock and Roll: The Economic Impact oI the GrateIul Dead on a

Local Economy." Journal of Cultural Economics 21:41-55.

Gladwell, Malcolm. 2000. The Tipping Point. How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference.

New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Goss, Kristin. 2000. Bettertogether . the report of the Saguaro Seminar on Civic Engagement in

America. Cambridge, MA: Saguaro Seminar Civic Engagement in America John F.

Kennedy School oI Government Harvard University.

http://www.bettertogether.org/bt5Freport.pdI.

HDA. 2000. Art for health. a review of good practice in communitv-based arts profects and

initiatives which impact on health and wellbeing. London: Health Development Agency.

http://www.hda-online.org.uk/downloads/pdIs/arts5Fmono.pdI.

Hetland, Lois. 2000. "Listening to Music Enhances Spatial-Temporal Reasoning: Evidence oI the

'Mozart EIIect'." Journal of Aesthetic Education 34:105-148.

Jackson, Ernest. 1979. "The impact oI arts enrichment instruction on selI-concept, attendance,

motivation, and academic perIormance." Pp. v, 135 leaves : p., Iorms. New York:

Fordham University.

Kling, Robert W., Charles F. Revier, and Karin A. Sable. 2001. "Estimating the Public Good

Value oI Preserving a Local Historic Landmark: The role oI non-substitutability and

inIormation in contingent valuation." Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University.

Krieger, Alex. 2001. "Community builders." Architecture 90.

Laing, Dave, and Norton York. 2000. "The Value oI Music in London." Cultural Trends 10.

Landry, Charles, Lesley Greene, Franois Matarasso, and Franco Bianchini. 1996. The Art of

Regeneration. Urban Renewal through Cultural Activitv. Stroud: Comedia.

Lynch, Ruth Torkelson, and Deanne Chosa. 1996. "Group-oriented community-based expressive

arts programming Ior individuals with disabilities: Participant satisIaction and

perceptions oI psychosocial impact."

Matarasso, Franois. 1997. Use or ornament? . the social impact of participation in the Arts.

Stroud, Glos.: Comedia.

. 1999. Magic, Mvths and Monev . The Impact of the English National Ballet on Tour. Stroud:

Comedia.

Matzke, Christine. 2000. "'Healthy community arts, healthy communities': Community Arts

ConIerence, Exhibition Fair, and Festival." Research in Drama Education 5:131 - 139.

McCarthy, Kevin. 2002. "Building an Understanding oI the BeneIits oI Participation in the Arts."

Unpublished proposal submitted by the RAND Corporation to the Wallace-Reader's

Digest Funds.

Mitchell, Clare J. A. 1993. "Economic Impact oI the Arts: Theatre Festivals in Small Ontario

Communities." Journal of Cultural Economics 17:55-67.

24

Murphy, Eileen M. 1995. "The impact oI cultural organizations on urban revitalization projects as

exempliIied in the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation." Pp. iv, 85 leaves ;

p., 29 cm. Washington D.C.: American University.

NALAA. 1994. Arts in the local economv. final report. Washington: National Assembly oI Local

Arts Agencies.

OAC. 2002. "Community Arts Organizations Program Guidelines." Ontario Arts Council.

Ogilvie, Robert S. 2000. Communitv building . increasing participation and taking action .

prepared for the 7th Street/McClvmonds Neighborhood Initiative. Berkeley, CaliI.:

University oI CaliIornia Berkeley Institute oI Urban and Regional Development.

O'Hagan, John W., and Christopher T. DuIIy. 1987. The performing arts and the public purse. An

economic analvsis. Dublin: The Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaion.

Palmer, John P. 2002. "Bread and Circuses: The Local BeneIits oI Sports and Cultural

Businesses." C.D. Howe Institute Commentarv 161.

Perryman, M Ray. 2001. "The Arts, culture, and the Texas economy: The catalyst Ior creativity

and the incubator Ior progress." Bavlor Business Review 19:8-9.

Port Authority oI New York and New Jersey, Cultural Assistance Center. 1983. "The Arts as an

Industry: Their Economic Importance to the New York-New Jersey Metropolitan

Region." New York, NY: Port Authority oI New York and New Jersey.

Preston, James C. 1983. "Patterns in Nongovernmental Community Action in Small

Communities." Journal of the Communitv Development Societv 14:83-94.

Radich, Anthony J. (Ed.). 1987. Economic impact of the arts. a sourcebook. Denver, CO:

National ConIerence oI State Legislatures.

Randall, Paula, Dian Magie, and Christine E. Miller. 1997. Art works' . prevention programs for

vouth & communities. Rockville, MD: National Endowment Ior the Arts and the Center

Ior Substance Abuse Prevention.

Remer, Jane. 1990. Changing schools through the arts . how to build on the power of an idea.

New York: ACA Books.

Rolph, Stephen. 2001. "Impact oI the Arts: A study oI the social and economic impacts oI the arts

in Essex in 1999/2000." Pp. 42. ChelmsIord: Essex County Council.

Sable, Karin A., and Robert W. Kling. 2001. "The Double Public Good: A Conceptual

Framework Ior "Shared Experience" Values Associated with Heritage Conservation."

Journal of Cultural Economics 25:77-89.

SATC. 1998. 1997 opera in the outback . economic and social impact studv. Adelaide, S. Aust.:

South Australian Tourism Commission Arts SA.

SCDCAC. 2001. "The arts and culture in San Diego : economic impact report, 2000." San Diego,

CaliI.: City oI San Diego Commission Ior Arts and Culture.

Seaman, Bruce A. 1997. "Arts Impact Studies: A Fashionable Excess." Pp. pages 723-55 in

Cultural economics. The arts, the heritage and the media industries. Jolume 2. Elgar

Reference Collection. International Librarv of Critical Writings in Economics, vol. 80.

Cheltenham, U.K, edited by Ruth ed Towse. and Lyme, N.H.: Elgar; distributed by

American International Distribution Corporation Williston.

Seham, Jenny C. 1997. "The eIIects on at-risk children oI an in-school dance program." Pp. iv,

101 leaves ; p., 29 cm.: Adelphi University.

Sharp, Caroline. 2001. "Developing Young Children's Creativity through the Arts: What Does

Research have to OIIer?" Pp. 36. Slough: National Federation Ior Educational Research.

Singer, Molly. 2000. "Culture Works: Cultural Resources as economic development tools."

Public Management 82:11-16.

Stanziola, Javier. 1999. Arts, government and communitv revitali:ation. Ashgate: Aldershot,

U.K.; BrookIield, Vt. and Sydney.

25

26

Stern, Mark J. 1999. "Is All the Worl Philadelphia? A multi-city study oI arts and cultural

organizations, diversity, and urban revitalization." Philadelphia: University oI

Pennsylvania School oI Social Work.

. 2001. "Social Impact oI the Arts Project: Summary oI Findings." Philadelphia: University oI

Pennsylvania School oI Social Work.

Stern, Mark J, Laura AmroIel, Gina Dyer, and Alison Wok. 1994. "The Embeddedness oI

Community Cultural Institutions." Philadelphia: University oI Pennsylvania School oI

Social Work.

Stern, Mark J, and Susan C SeiIert. 2000. "Cultural Participation and Communities: The Role oI

Individual and Neighborhood EIIects." Philadeliphia: University oI Pennsylvania School

oI Social Work.

. 2002. "Culture Builds Community Evaluation Summary Report." Pp. 62. Philadelphia:

University oI Pennsylvania School oI Social Work.

Strom, Elizabeth. 1999. "Let's put on a show! PerIorming arts and urban revitalization in Newark,

New Jersey." Pp. 423-35 in Journal of Urban Affairs.

Thoits, Peggy A., and Lyndi N. Hewitt. 2001. "Volunteer Work and Well-Being." Journal of

Health and Social Behavior 42:115-131.

Throsby, David. 2001. Economics and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Travers, Tony, Eleanor Stokes, and Mark Kleinmann. 1997. "The Arts & Cultural Industries in

the London Economy." London: London Arts Board.

Trent, Allen W. 2000. Communitv . a collaborative action research profect in an arts impact

elementarv school. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University.

Turner, Francesca, and Peter Senior. 2000. A Powerful Force for Good. Culture, health and the

arts- an anthologv. Manchester: Manchester Metropolitan University.

Walesh, Kim and Doug Henton. 2001. "The Creative Community--Leveraging Creativity and

Cultural Participation Ior Silicon Valley's Economic and Civic Future." San Jose, CA:

Collaborative Economics.

Weitz, Judith. 1996. Coming up taller. arts and humanities programs for children and vouth at

risk. Washington, DC: President's Committee on the Arts and the Humanities.

Williams, Deidre. 1995. Creating social capital . a studv of the long-term benefits from

communitv based arts funding. Adelaide, S. Aust.: Community Arts Network oI South

Australia.

. 1997. How the arts measure up . Australian research into social impact. Stroud: Comedia.

Winner, Ellen, and Lois Hetland. 2000. "The Arts and Academic Improvement: What the

Evidence Shows." Special Issue of the Journal of Aesthetic Education 34.

Wollheim, Bruno. 2000. "Culture makes communities." York, England: Joseph Rowntree

Foundation.

Zukin, Sharon. 1989. Loft Living. Culture and Capital in Urban Change. New Brunswick, NJ:

Rutgers University Press.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Community Arts ImpactsDokument27 SeitenCommunity Arts ImpactsjennyleecraigNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Sin TítuloDokument19 Seiten3 Sin Títuloroggerz8Noch keine Bewertungen

- Art and CultureDokument6 SeitenArt and Culturemonakhanawan12345678Noch keine Bewertungen

- Getting in On The Act 2011OCT19 PDFDokument46 SeitenGetting in On The Act 2011OCT19 PDFAlejandro JiménezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Socially Engaged Art Education: Defining and Defending The PracticeDokument21 SeitenSocially Engaged Art Education: Defining and Defending The PracticeAurelio CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pbs PaperDokument7 SeitenPbs Paperapi-483705271Noch keine Bewertungen

- Uloga Na MuzeiteDokument10 SeitenUloga Na MuzeiteBobi BTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use or OrnamentDokument111 SeitenUse or OrnamentprimacyOfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts As Dialogic Practice: Deriving Lessons For Change From Community-Based Art-Making For International DevelopmentDokument16 SeitenArts As Dialogic Practice: Deriving Lessons For Change From Community-Based Art-Making For International DevelopmentgjkghgjhfgjhfgjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creativity Through A Rhetorical LensDokument20 SeitenCreativity Through A Rhetorical LensCatarina MartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art and Culture in Communities Unpacking ParticipationDokument12 SeitenArt and Culture in Communities Unpacking ParticipationDalonPetrelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creative Cities A 10-Year Research AgendaDokument24 SeitenCreative Cities A 10-Year Research AgendaMelissa Ann PatanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preview - Social Entrepreneurship in The Creative SectorDokument40 SeitenPreview - Social Entrepreneurship in The Creative Sectormiroslava.dimitrova.2022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arts Funding, Austerity and The Big Society - Remaking The Case For The Arts - RSA PamphletsDokument40 SeitenArts Funding, Austerity and The Big Society - Remaking The Case For The Arts - RSA PamphletsThe RSANoch keine Bewertungen

- Grande Área: Ciências Humanas e Ciências Sociais Aplicadas: Adapted FromDokument3 SeitenGrande Área: Ciências Humanas e Ciências Sociais Aplicadas: Adapted FromTeacher AlineNoch keine Bewertungen

- NShykoluk - Research Proposal (Final)Dokument14 SeitenNShykoluk - Research Proposal (Final)Natalie ShykolukNoch keine Bewertungen

- Re-Structure UnlikelyDokument153 SeitenRe-Structure UnlikelyJan BrueggemeierNoch keine Bewertungen

- REBEL: Producing Publics Through Playful EvaluationDokument21 SeitenREBEL: Producing Publics Through Playful EvaluationmarshabradfieldNoch keine Bewertungen

- InteractiveperformanceDokument20 SeitenInteractiveperformanceluamsmarinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- CRANE, Diana - The Production of Culture (Cap.8) PDFDokument12 SeitenCRANE, Diana - The Production of Culture (Cap.8) PDFlukdisxitNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Agencies Civil Public PartnershipDokument17 SeitenNew Agencies Civil Public PartnershipМилица ШојићNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S2199853122002591 MainDokument20 Seiten1 s2.0 S2199853122002591 Mainsolalilelo98Noch keine Bewertungen

- ArtandCommunityDevelopment Article 050400Dokument15 SeitenArtandCommunityDevelopment Article 050400Kiss AnnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Policy What Is It, Who Makes It and Why Does It Matter-2Dokument4 SeitenCultural Policy What Is It, Who Makes It and Why Does It Matter-2Adel Farouk Vargas Espinosa-EfferettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts Education and CitizenshipDokument9 SeitenArts Education and CitizenshipAndreina JimenezNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Arts Management To Cultural AdministrationDokument16 SeitenFrom Arts Management To Cultural AdministrationAdelina Turcu100% (1)

- Art of Dying - John Knell (2005)Dokument11 SeitenArt of Dying - John Knell (2005)Mission Models MoneyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Importance of Art To SocietiesDokument4 SeitenThe Importance of Art To SocietiesRewanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Visual Art-Making ConnectionsDokument12 SeitenVisual Art-Making ConnectionsTilos CherithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijcm.16.1.31 BartleetDokument19 SeitenIjcm.16.1.31 Bartleetemine.karadenizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Museums and Impact How Do We Measure The Impact of Museums?Dokument14 SeitenMuseums and Impact How Do We Measure The Impact of Museums?ppaaneriNoch keine Bewertungen

- IeltsDokument2 SeitenIeltsĐồng Mộc Tuyết DiaVicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economical Benefits of Art Anis 22222Dokument4 SeitenEconomical Benefits of Art Anis 22222Dhaqabaa DhugaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creating Citizens: Liberal Arts, Civic Engagement, and the Land-Grant TraditionVon EverandCreating Citizens: Liberal Arts, Civic Engagement, and the Land-Grant TraditionBrigitta R. BrunnerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laing & Mair (2015)Dokument18 SeitenLaing & Mair (2015)Ionut IugaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humanities-How Art Was UnderstoodDokument2 SeitenHumanities-How Art Was UnderstoodMadora SamuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 19 Music and SocietyDokument11 SeitenUnit 19 Music and SocietynorthernmeldrewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dekker, E. & Morea, V. (2023) Realizing The Values of Art. Making Space For Cultural Civil SocietyDokument161 SeitenDekker, E. & Morea, V. (2023) Realizing The Values of Art. Making Space For Cultural Civil SocietylucprickaertsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Room: Rafael Romero Dogtime 2Dokument32 SeitenThe Room: Rafael Romero Dogtime 2RafaelRompeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solis IndieDokument20 SeitenSolis Indieapi-542016147Noch keine Bewertungen

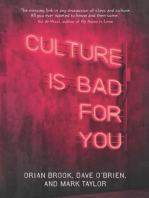

- Culture is bad for you: Inequality in the cultural and creative industriesVon EverandCulture is bad for you: Inequality in the cultural and creative industriesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Issue ReportDokument7 SeitenIssue Reportapi-470135705Noch keine Bewertungen

- Art EssayDokument2 SeitenArt EssaycalielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mulungushi University STUDENT NUMBER:201904111 Question Number: Two (2) Question: Discuss The Relenvance of SocialDokument7 SeitenMulungushi University STUDENT NUMBER:201904111 Question Number: Two (2) Question: Discuss The Relenvance of SocialSitabile PittersNoch keine Bewertungen

- V835 TurriniDokument11 SeitenV835 TurriniAlina MasgrasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Charactristics of Pop CultureDokument4 SeitenCharactristics of Pop CultureAni Vie MaceroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why The Arts Should MatterDokument3 SeitenWhy The Arts Should MatterJulia IngallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMM Capital Matters - How To Build Financial Resilience in The UK's Arts and Cultural Sector (21.12.10)Dokument71 SeitenMMM Capital Matters - How To Build Financial Resilience in The UK's Arts and Cultural Sector (21.12.10)AmbITionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impacto Del Arte en La SociedadDokument41 SeitenImpacto Del Arte en La SociedadDaniel EspinosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural VitalityDokument104 SeitenCultural VitalitystefisteffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Look Out... Look inDokument8 SeitenLook Out... Look inThe RSANoch keine Bewertungen

- Allen Et Al. 2004 The Art of RehabilitationDokument6 SeitenAllen Et Al. 2004 The Art of RehabilitationDragos DragomirNoch keine Bewertungen

- ARTICULO - 2016 - Connecting Social Work and Activism in The Arts Through Continuing Professional EducationDokument14 SeitenARTICULO - 2016 - Connecting Social Work and Activism in The Arts Through Continuing Professional EducationLic EducaciónNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Can We Engage More Young People in Arts and Culture?: A Guide To What Works For Funders and Arts OrganisationsDokument60 SeitenHow Can We Engage More Young People in Arts and Culture?: A Guide To What Works For Funders and Arts OrganisationsPriya KashyapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Synthesis PaperDokument9 SeitenSynthesis Papersidmur321Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kaplan Essay 2Dokument1 SeiteKaplan Essay 2Vassilis LaliotisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creative Placemaking in Community Planning and Development An Introduction To Artplace AmericaDokument8 SeitenCreative Placemaking in Community Planning and Development An Introduction To Artplace AmericaNour AlGazoulyNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Arts Management To Cultural Administration PDFDokument16 SeitenFrom Arts Management To Cultural Administration PDFCarla LăzăuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gilson 2011 HypatiaDokument25 SeitenGilson 2011 HypatiaMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shadow Ownership and SSR in Afghanistan: Antonio GiustozziDokument17 SeitenShadow Ownership and SSR in Afghanistan: Antonio GiustozziMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- PapersDokument32 SeitenPapersMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geopolitics at The Margins J SharpDokument10 SeitenGeopolitics at The Margins J SharpMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liebow Nabina Internalized Oppression and Its Varied Moral HarmsDokument17 SeitenLiebow Nabina Internalized Oppression and Its Varied Moral HarmsMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baudrillard S Philosophy of Seduction: An Overview.: DR Robert Miller Existentialist Society Lecture December 2004 1Dokument9 SeitenBaudrillard S Philosophy of Seduction: An Overview.: DR Robert Miller Existentialist Society Lecture December 2004 1Mehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psichopolitical ValidityDokument21 SeitenPsichopolitical ValidityMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review of Ordinary Affects PDFDokument3 SeitenReview of Ordinary Affects PDFMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 PB PDFDokument4 Seiten1 PB PDFMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anne Aly Et Al Rethinking Countering Violent Extremism: Implementing The Role of Civil SocietyDokument12 SeitenAnne Aly Et Al Rethinking Countering Violent Extremism: Implementing The Role of Civil SocietyMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Meaning and Philosophical Method: CitationDokument25 SeitenSocial Meaning and Philosophical Method: CitationMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spring 2016 Newsletter: in This IssueDokument13 SeitenSpring 2016 Newsletter: in This IssueMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mundane Governance Alison Marlin PDFDokument4 SeitenMundane Governance Alison Marlin PDFMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Biopolitics To Noopolitics. Architecture & Mind in The Age of Communication and InformationDokument297 SeitenFrom Biopolitics To Noopolitics. Architecture & Mind in The Age of Communication and InformationMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- HauptmannDokument6 SeitenHauptmannMehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ORIT HALPERN. Beautiful Data: A History of Vision and Reason Since 1945.Dokument2 SeitenORIT HALPERN. Beautiful Data: A History of Vision and Reason Since 1945.Mehdi FaizyNoch keine Bewertungen