Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Pali - From Wikipedia

Hochgeladen von

Patrick CoCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Pali - From Wikipedia

Hochgeladen von

Patrick CoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Pali

1

Pali

Pali

Pi

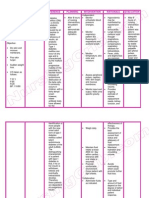

Pronunciation Sanskrit pronunciation:[pali]

Spoken in Cambodia, Bangladesh, India, Laos, Burma,

Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam

Language extinction No native speakers, used as a literary and liturgical language only

Language family Indo-European

Indo-Iranian

Indo-Aryan

Pali

Writing system Brhm and derived scripts and Latin alphabet (refer to article)

Language codes

ISO 639-1 pi

ISO 639-2 pli

ISO 639-3 pli

This page contains Indic text. Without rendering support you may see

irregular vowel positioning and a lack of conjuncts. More...

Pali

2

Plate 10 from C. Faulmann: Illustrirte Geschichte der Schrift

[1]

(1880). The upper half

shows a text in Sanskrit (praise of Vishnu), written in Devanagari. For the script, while

the lower half shows a text in Pali from a Buddhist ceremonial scripture called

"Kammuwa" from Burma (probably in old Mon script). pp.485f.

[2]

of that book.

Pli (also Pi) is a Middle Indo-Aryan

language (or Prakrit) of the Indian

subcontinent. It is best known as the

language of many of the earliest extant

Buddhist scriptures, as collected in the

Pi Canon or Tipitaka, and as the

liturgical language of Theravada

Buddhism.

Origin and development

Etymology of the name

The word Pali itself signifies "line" or

"(canonical) text". This name for the

language seems to have its origins in

commentarial traditions, wherein the

Pali (in the sense of the line of original

text quoted) was distinguished from the commentary or vernacular translation that followed it in the manuscript. As

such, the name of the language has caused some debate among scholars of all ages; the spelling of the name also

varies, being found with both long "" [] and short "a" [a], and also with either a retroflex [] or non-retroflex [l] "l"

sound, as in the ISO 15919/ALA-LC rendering, Pi. To this day, there is no single, standard spelling of the term; all

four spellings can be found in textbooks. R.C. Childers translates the word as "series" and states that the language

"bears the epithet in consequence of the perfection of its grammatical structure".

[3]

Classification

Pali is a literary language of the Prakrit language family. When the canonical texts were written down in Sri Lanka in

the first century BCE, Pali stood close to a living language; this is not the case for the commentaries.

[4]

Despite

excellent scholarship on this problem, there is persistent confusion as to the relation of Pi to the vernacular spoken

in the ancient kingdom of Magadha, which was located around modern-day Bihr.

Pali as a Middle Indo-Aryan language is different from Sanskrit not so much with regard to the time of its origin as

to its dialectal base, since a number of its morphological and lexical features betray the fact that it is not a direct

continuation of gvedic Vedic Sanskrit; rather it descends from a dialect (or a number of dialects) that was, despite

many similarities, different from gvedic.

[5]

Early history

In Theravada Buddhism

Many Theravada sources refer to the Pali language as "Magadhan" or the "language of Magadha". This identification

first appears in the commentaries, and may have been an attempt by Buddhists to associate themselves more closely

with the Mauryans. The Buddha taught in Magadha, but the four most important places in his life are all outside of it.

It is likely that he taught in several closely related dialects of Middle Indo-Aryan, which had a very high degree of

mutual intelligibility. There is no attested dialect of Middle Indo-Aryan with all the features of Pali. Pali has some

commonalities with both the Ashokan inscriptions at Girnar in the West of India, and at Hathigumpha, Bhubaneswar,

Odisha in the East. Similarities to the Western inscription may be misleading, because the inscription suggests that

the Ashokan scribe may not have translated the material he received from Magadha into the vernacular of the people

Pali

3

there. Whatever the relationship of the Buddha's speech to Pali, the Canon was eventually transcribed and preserved

entirely in it, while the commentarial tradition that accompanied it (according to the information provided by

Buddhaghosa) was translated into Sinhalese and preserved in local languages for several generations.

In Sri Lanka, Pali is thought to have entered into a period of decline ending around the 4th or 5th century (as Sanskrit

rose in prominence, and simultaneously, as Buddhism's adherents became a smaller portion of the subcontinent), but

ultimately survived. The work of Buddhaghosa was largely responsible for its reemergence as an important scholarly

language in Buddhist thought. The Visuddhimagga and the other commentaries that Buddhaghosa compiled codified

and condensed the Sinhalese commentarial tradition that had been preserved and expanded in Sri Lanka since the 3rd

century BCE.

Early western views

T.W. Rhys Davids in his book Buddhist India,

[6]

and Wilhelm Geiger in his book Pali Literature and Language,

suggested that Pali may have originated as a form of lingua franca or common language of culture among people

who used differing dialects in North India, used at the time of the Buddha and employed by him. Another scholar

states that at that time it was "a refined and elegant vernacular of all Aryan-speaking people."

[7]

Modern scholarship

has not arrived at a consensus on the issue; there are a variety of conflicting theories with supporters and

detractors.

[8]

After the death of the Buddha, Pali may have evolved among Buddhists out of the language of the

Buddha as a new artificial language.

[9]

R.C. Childers, who held to the theory that Pali was Old Magadhi, wrote: "Had

Gautama never preached, it is unlikely that Magadhese would have been distinguished from the many other

vernaculars of Hindustan, except perhaps by an inherent grace and strength which make it a sort of Tuscan among

the Prakrits."

[10]

According to K.R. Norman, it is likely that the viharas in North India had separate collections of material, preserved

in the local dialect. In the early period it is likely that no degree of translation was necessary in communicating this

material to other areas. Around the time of Ashoka there had been more linguistic divergence, and an attempt was

made to assemble all the material. It is possible that a language quite close to the Pali of the canon emerged as a

result of this process as a compromise of the various dialects in which the earliest material had been preserved, and

this language functioned as a lingua franca among Eastern Buddhists in India from then on. Following this period,

the language underwent a small degree of Sanskritisation (i.e., MIA bamhana -> brahmana, tta -> tva in some

cases).

[11]

Modern scholarship

Bhikkhu Bodhi, summarizing the current state of scholarship, states that the language is "closely related to the

language (or, more likely, the various regional dialects) that the Buddha himself spoke." He goes on to write:

Scholars regard this language as a hybrid showing features of several Prakrit dialects used around the third

century BCE, subjected to a partial process of Sanskritization. While the language is not identical with any the

Buddha himself would have spoken, it belongs to the same broad linguistic family as those he might have used

and originates from the same conceptual matrix. This language thus reflects the thought-world that the Buddha

inherited from the wider Indian culture into which he was born, so that its words capture the subtle nuances of

that thought-world.

[12]

According to A.K. Warder, the Pali language is a Prakrit language used in a region of western India.

[13]

Warder

associates Pali with the Indian realm (janapada) of Avanti, where the Sthavira sect was centered.

[14]

Following the

initial split in the Buddhist community, the Sthavira branch of Buddhism became influential in western and southern

India, while the Mahsghika branch became influential in central and eastern India.

[15]

Akira Hirakawa and Paul

Groner also associate Pali with west India and the Sthavira sect, citing inscriptions at Girnar in Gujarat, India, which

are linguistically closest to the Pali language.

[16]

Pali

4

Pali today

Today Pali is studied mainly to gain access to Buddhist scriptures, and is frequently chanted in a ritual context. The

secular literature of Pali historical chronicles, medical texts, and inscriptions is also of great historical importance.

The great centers of Pali learning remain in the Theravada nations of Southeast Asia: Burma, Sri Lanka, Thailand,

Laos, and Cambodia. Since the 19th century, various societies for the revival of Pali studies in India have promoted

awareness of the language and its literature, perhaps most notably the Maha Bodhi Society founded by Anagarika

Dhammapala.

In Europe, the Pali Text Society has been a major force in promoting the study of Pali by Western scholars since its

founding in 1881. Based in the United Kingdom, the society publishes romanized Pali editions, along with many

English translations of these sources. In 1869, the first Pali Dictionary was published using the research of Robert

Caesar Childers, one of the founding members of the Pali Text Society. It was the first Pali translated text in English

and was published in 1872. Childers's dictionary later received the Volney Prize in 1876.

The Pali Text Society was in part founded to compensate for the very low level of funds allocated to Indology in late

19th-century England and the rest of the UK; incongruously, the citizens of the UK were not nearly so robust in

Sanskrit and Prakrit language studies as Germany, Russia, and even Denmark. Without the inspiration of colonial

holdings such as the former British occupation of Sri Lanka and Burma, institutions such as the Danish Royal

Library have built up major collections of Pali manuscripts, and major traditions of Pali studies.

Lexicon

Virtually every word in Pi has cognates in the other Prakritic Middle Indo-Aryan languages, e.g., the Jain Prakrits.

The relationship to earlier Sanskrit (e.g., Vedic language) is less direct and more complicated. Historically, influence

between Pali and Sanskrit has been felt in both directions. The Pali language's resemblance to Sanskrit is often

exaggerated by comparing it to later Sanskrit compositions which were written centuries after Sanskrit ceased to

be a living language, and are influenced by developments in Middle Indic, including the direct borrowing of a

portion of the Middle Indic lexicon; whereas, a good deal of later Pali technical terminology has been borrowed from

the vocabulary of equivalent disciplines in Sanskrit, either directly or with certain phonological adaptations.

Post-canonical Pali also possesses a few loan-words from local languages where Pali was used (e.g. Sri Lankans

adding Sinhalese words to Pali). These usages differentiate the Pali found in the Suttapiaka from later compositions

such as the Pali commentaries on the canon and folklore (e.g., the stories of the Jtaka commentaries), and

comparative study (and dating) of texts on the basis of such loan-words is now a specialized field unto itself.

Pali was not exclusively used to convey the teachings of the Buddha, as can be deduced from the existence of a

number of secular texts, such as books of medical science/instruction, in Pali. However, scholarly interest in the

language has been focused upon religious and philosophical literature, because of the unique window it opens on one

phase in the development of Buddhism.

Emic views of Pali

Although Sanskrit was said in the Brahmanical tradition to be the unchanging language spoken by the gods, in which

each word had an inherent significance, this view of language was not shared in the early Buddhist tradition, in

which words were only conventional and mutable signs.

[17]

Neither the Buddha nor his early followers shared the

Brahmins' reverence for the Vedic language or its sacred texts. This view of language naturally extended to Pali, and

may have contributed to its usage (as an approximation or standardization of local Middle Indic dialects) in place of

Sanskrit. However, by the time of the compilation of the Pali commentaries (4th or 5th century), Pali was regarded

as the natural language, the root language of all beings.

[18]

Comparable to Ancient Egyptian, Latin or Hebrew in the mystic traditions of the West, Pali recitations were often

thought to have a supernatural power (which could be attributed to their meaning, the character of the reciter, or the

Pali

5

qualities of the language itself), and in the early strata of Buddhist literature we can already see Pali dhras used as

charms, e.g. against the bite of snakes. Many people in Theravada cultures still believe that taking a vow in Pali has a

special significance, and, as one example of the supernatural power assigned to chanting in the language, the

recitation of the vows of Agulimla are believed to alleviate the pain of childbirth in Sri Lanka. In Thailand, the

chanting of a portion of the Abhidhammapiaka is believed to be beneficial to the recently departed, and this

ceremony routinely occupies as much as seven working days. Interestingly, there is nothing in the latter text that

relates to this subject, and the origins of the custom are unclear.

Phonology

With regard to its phonology, R.C. Childers compared Pali to Italian: "Like Italian, Pali is at once flowing and

sonorous: it is a characteristic of both languages that nearly every word ends in a vowel, and that all harsh

conjunctions are softened down by assimilation, elision, or crasis, while on the other hand both lend themselves

easily to the expression of sublime and vigorous thought."

[19]

Vowels

Height Backness

Front Central Back

High i [i] [i] u [u] [u]

Mid e [e], [e] a [] o [o], [o]

Low [a]

Long and short vowels are only contrastive in open syllables; in closed syllables, all vowels are always short. Short

and long e and o are in complementary distribution: the short variants occur only in closed syllables, the long

variants occur only in open syllables. Short and long e and o are therefore not distinct phonemes.

A sound called anusvra (Skt.; Pali: nigghahita), represented by the letter (ISO 15919) or (ALA-LC) in

romanization, and by a raised dot in most traditional alphabets, originally marked the fact that the preceding vowel

was nasalized. That is, a, i and u represented [], [] and []. In many traditional pronunciations, however, the

anusvra is pronounced more strongly, like the velar nasal [], so that these sounds are pronounced instead [], []

and []. However pronounced, never follows a long vowel; , and are converted to the corresponding short

vowels when is added to a stem ending in a long vowel, e.g. kath + becomes katha, not *kath, dev +

becomes devi, not *dev.

Consonants

The table below lists the consonants of Pali. In bold is the transliteration of the letter in traditional romanization, and

in square brackets its pronunciation transcribed in the IPA.

Pali

6

Labial Dental Alveolar Retroflex Palatal Velar Glottal

(bilabial) (labiodental) central lateral central lateral

Stop Nasal m [m] n [n] [] [] ( [])

voiceless unaspirated p [p] t [t] [] c [t] k [k]

aspirated ph [p] th [t] h [] ch[t] kh [k]

voiced unaspirated b [b] d [d] [] j [d] g []

aspirated bh [b] dh [d] h [] jh [d] gh []

Fricative s [s] h [h]

Approximant unaspirated v [] l [l] r [] ( []) y [j]

aspirated (h [])

Of the sounds listed above only the three consonants in parentheses, , , and h, are not distinct phonemes in Pali:

only occurs before velar stops and , and h are allophones of single , and h between vowels.

Morphology

Pali is a highly inflected language, in which almost every word contains, besides the root conveying the basic

meaning, one or more affixes (usually suffixes) which modify the meaning in some way. Nouns are inflected for

gender, number, and case; verbal inflections convey information about person, number, tense and mood.

Nominal inflection

Pali nouns inflect for three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, neuter) and two numbers (singular, and

plural). The nouns also, in principle, display eight cases: nominative or paccatta case, vocative, accusative or

upayoga case, instrumental or karaa case, dative or sampadna case, ablative, genitive or smin case, and

locative or bhumma case; however, in many instances, two or more of these cases are identical in form; this is

especially true of the genitive and dative cases.

a-stems

a-stems, whose uninflected stem ends in short a (//), are either masculine or neuter. The masculine and neuter forms

differ only in the nominative, vocative, and accusative cases.

Masculine (loka- "world") Neuter (yna- "carriage")

Singular Plural Singular Plural

Nominative loko lok yna ynni

Vocative loka

Accusative loka loke

Instrumental lokena lokehi ynena ynehi

Ablative lok (lokamh, lokasm; lokato) yn (ynamh, ynasm; ynato)

Dative lokassa (lokya) lokna ynassa (ynya) ynna

Genitive lokassa ynassa

Locative loke (lokasmi) lokesu yne (ynasmi) ynesu

Pali

7

-stems

Nouns ending in (/a/) are almost always feminine.

Feminine (kath- "story")

Singular Plural

Nominative kath kathyo

Vocative kathe

Accusative katha

Instrumental kathya kathhi

Ablative

Dative kathna

Genitive

Locative kathya, kathya kathsu

i-stems and u-stems

i-stems and u-stems are either masculine or neuter. The masculine and neuter forms differ only in the nominative and

accusative cases. The vocative has the same form as the nominative.

Masculine (isi- "seer") Neuter (akkhi- "fire")

Singular Plural Singular Plural

Nominative isi isayo, is akkhi, akkhi akkh, akkhni

Vocative

Accusative isi

Instrumental isin isihi, ishi akkhin akkhihi, akkhhi

Ablative isin, isito akkhin, akkhito

Dative isino isina, isna akkhino akkhina, akkhna

Genitive isissa, isino akkhissa, akkhino

Locative isismi isisu, issu akkhismi akkhisu, akkhsu

Masculine (bhikkhu- "monk") Neuter (cakkhu- "eye")

Singular Plural Singular Plural

Nominative bhikkhu bhikkhavo, bhikkh cakkhu, cakkhu cakkhni

Vocative

Accusative bhikkhu

Instrumental bhikkhun bhikkhhi cakkhun cakkhhi

Ablative

Dative bhikkhuno bhikkhna cakkhuno cakkhna

Genitive bhikkhussa, bhikkhuno bhikkhna, bhikkhunna cakkhussa, cakkhuno cakkhna, cakkhunna

Locative bhikkhusmi bhikkhsu cakkhusmi cakkhsu

Pali

8

Linguistic analysis of a Pali Text

From the opening of the Dhammapada:

Manopubbagam dhamm, manoseh manomay;

Manas ce paduhena, bhsati v karoti v,

Tato nam dukkha anveti, cakka'va vahato pada.

Element for element gloss:

Mano-pubba-gam= dhamm=, mano-seh= mano-may=;

Mind-before-going=m.pl.nom. dharma=m.pl.nom., mind-foremost=m.pl.nom. mind-made=m.pl.nom.

Manas= ce paduh=ena, bhsa=ti v karo=ti v,

Mind=n.sg.inst. if corrupted=n.sg.inst. speak=3.sg.pr. either act=3.sg.pr. or,

Ta=to na dukkha anv-e=ti, cakka 'va vahat=o pad=a.

That=from him suffering after-go=3.sg.pr., wheel as carrying(beast)=m.sg.gen. foot=n.sg.acc.

The three compounds in the first line literally mean:

manopubbagama "whose precursor is mind", "having mind as a fore-goer or leader"

manoseha "whose foremost member is mind", "having mind as chief"

manomaya "consisting of mind" or "made by mind"

The literal meaning is therefore: "The dharmas have mind as their leader, mind as their chief, are made of/by mind. If

[someone] either speaks or acts with a corrupted mind, from that [cause] suffering goes after him, as the wheel [of a

cart follows] the foot of a draught animal."

A slightly freer translation by Acharya Buddharakkhita

Mind precedes all mental states. Mind is their chief; they are all mind-wrought.

If with an impure mind a person speaks or acts suffering follows him

like the wheel that follows the foot of the ox.

Pali and Ardha-Magadhi

The most archaic of the Middle Indo-Aryan languages are the inscriptional Aokan Prakrit on the one hand and Pli

and Ardhamgadh on the other, both literary languages.

The Indo-Aryan languages are commonly assigned to three major groups - Old, Middle and New Indo-Aryan -, a

linguistic and not strictly chronological classification as the MIA languages are not younger than ('Classical')

Sanskrit. And a number of their morphophonological and lexical features betray the fact that they are not direct

continuations of gvedic Sanskrit, the main base of 'Classical' Sanskrit; rather they descend from dialects which,

despite many similarities, were different from gvedic and in some regards even more archaic.

MIA languages, though individually distinct, share features of phonology and morphology which characterize them

as parallel descendants of Old Indo-Aryan. Various sound changes are typical of the MIA phonology:

(1) The vocalic liquids '' and '' are replaced by 'a', 'i' or 'u'; (2) the diphthongs 'ai' and 'au' are monophthongized to 'e'

and 'o'; (3) long vowels before two or more consonants are shortened; (4) the three sibilants of OIA are reduced to

one, either '' or 's'; (5) the often complex consonant clusters of OIA are reduced to more readily pronounceable

forms, either by assimilation or by splitting; (6) single intervocalic stops are progressively weakened; (7) dentals are

palatalized by a following '-y-'; (8) all final consonants except '-' are dropped unless they are retained in 'sandhi'

junctions.

The most conspicuous features of the morphological system of these languages are: loss of the dual; thematicization

of consonantal stems; merger of the f. 'i-/u-' and '-/-' in one '-/-' inflexion, elimination of the dative, whose

Pali

9

functions are taken over by the genitive, simultaneous use of different case-endings in one paradigm; employment of

'mahya' and 'tubhya' as genitives and 'me' and 'te' as instrumentals; gradual disappearance of the middle voice;

coexistence of historical and new verbal forms based on the present stem; and use of active endings for the passive.

In the vocabulary, the MIA languages are mostly dependent on Old Indo-Aryan, with addition of a few so-called

'de' words of (often) uncertain origin.

Pali and Sanskrit

Although Pali cannot be considered a direct descendant of either Classical Sanskrit or of the older Vedic dialect , the

languages are obviously very closely related and the common characteristics of Pali and Sanskrit were always easily

recognized by those in India who were familiar with both. Indeed, a very large proportion of Pali and Sanskrit

word-stems are identical in form, differing only in details of inflection.

The connections were sufficiently well-known that technical terms from Sanskrit were easily converted into Pali by a

set of conventional phonological transformations. These transformations mimicked a subset of the phonological

developments that had occurred in Proto-Pali. Because of the prevalence of these transformations, it is not always

possible to tell whether a given Pali word is a part of the old Prakrit lexicon, or a transformed borrowing from

Sanskrit. The existence of a Sanskrit word regularly corresponding to a Pali word is not always secure evidence of

the Pali etymology, since, in some cases, artificial Sanskrit words were created by back-formation from Prakrit

words.

The following phonological processes are not intended as an exhaustive description of the historical changes which

produced Pali from its Old Indic ancestor, but rather are a summary of the most common phonological equations

between Sanskrit and Pali, with no claim to completeness.

Vowels and diphthongs

Sanskrit ai and au always monophthongize to Pali e and o, respectively

Examples: maitr mett, auadha osadha

Sanskrit aya and ava likewise often reduce to Pali e and o

Examples: dhrayati dhreti, avatra otra, bhavati hoti

Sanskrit avi becomes Pali e (i.e. avi ai e)

Example: sthavira thera

Sanskrit appears in Pali as a, i or u, often agreeing with the vowel in the following syllable. also sometimes

becomes u after labial consonants.

Examples: kta kata, ta taha, smti sati, i isi, di dihi, ddhi iddhi, ju

uju, spa phuha, vddha vuddha

Sanskrit long vowels are shortened before a sequence of two following consonants.

Examples: knti khanti, rjya rajja, vara issara, tra tia, prva pubba

Pali

10

Consonants

Sound changes

The Sanskrit sibilants , , and s merge together as Pali s

Examples: araa saraa, doa dosa

The Sanskrit stops and h become and h between vowels (as in Vedic)

Example: cakrava cakkava, virha virha

Assimilations

General rules

Many assimilations of one consonant to a neighboring consonant occurred in the development of Pali, producing

a large number of geminate (double) consonants. Since aspiration of a geminate consonant is only phonetically

detectable on the last consonant of a cluster, geminate kh, gh, ch, jh, h, h, th, dh, ph and bh appear as kkh,

ggh, cch, jjh, h, h, tth, ddh, pph and bbh, not as khkh, ghgh etc.

When assimilation would produce a geminate consonant (or a sequence of unaspirated stop+aspirated stop) at the

beginning of a word, the initial geminate is simplified to a single consonant.

Examples: pra pa (not ppa), sthavira thera (not tthera), dhyna jhna (not jjhna),

jti ti (not ti)

When assimilation would produce a sequence of three consonants in the middle of a word, geminates are

simplified until there are only two consonants in sequence.

Examples: uttrsa uttsa (not utttsa), mantra manta (not mantta), indra inda (not indda),

vandhya vajha (not vajjha)

The sequence vv resulting from assimilation changes to bb

Example: sarva savva sabba, pravrajati pavvajati pabbajati, divya divva dibba

Total assimilation

Total assimilation, where one sound becomes identical to a neighboring sound, is of two types: progressive, where

the assimilated sound becomes identical to the following sound; and regressive, where it becomes identical to the

preceding sound.

Progressive assimilations

Internal visarga assimilates to a following voiceless stop or sibilant

Examples: dukta dukkata, dukha dukkha, dupraja duppaa, nikrodha

(=nikrodha) nikkodha, nipakva (=nipakva) nippakka, nioka nissoka, nisattva

nissatta

In a sequence of two dissimilar Sanskrit stops, the first stop assimilates to the second stop

Examples: vimukti vimutti, dugdha duddha, utpda uppda, pudgala puggala,

udghoa ugghosa, adbhuta abbhuta, abda sadda

In a sequence of two dissimilar nasals, the first nasal assimilates to the second nasal

Example: unmatta ummatta, pradyumna pajjunna

j assimilates to a following (i.e., j becomes )

Examples: praj pa, jti ti

The Sanskrit liquid consonants r and l assimilate to a following stop, nasal, sibilant, or v

Pali

11

Examples: mrga magga, karma kamma, vara vassa, kalpa kappa, sarva savva

sabba

r assimilates to a following l

Examples: durlabha dullabha, nirlopa nillopa

d sometimes assimilates to a following v, producing vv bb

Examples: udvigna uvvigga ubbigga, dvdaa brasa (beside dvdasa)

t and d may assimilate to a following s or y when a morpheme boundary intervenes

Examples: ut+sava ussava, ud+yna uyyna

Regressive assimilations

Nasals sometimes assimilate to a preceding stop (in other cases epenthesis occurs; see below)

Examples: agni aggi, tman atta, prpnoti pappoti, aknoti sakkoti

m assimilates to an initial sibilant

Examples: smarati sarati, smti sati

Nasals assimilate to a preceding stop+sibilant cluster, which then develops in the same way as such clusters

without following nasals (see Partial assimilations below)

Examples: tka tika tikkha, lakm lak lakkh

The Sanskrit liquid consonants r and l assimilate to a preceding stop, nasal, sibilant, or v

Examples: pra pa, grma gma, rvaka svaka, agra agga, indra inda,

pravrajati pavvajati pabbajati, aru assu

y assimilates to preceding non-dental/retroflex stops or nasals

Examples: cyavati cavati, jyoti joti, rjya rajja, matsya macchya maccha, lapsyate

lacchyate lacchati, abhygata abbhgata, khyti akkhti, sakhy sakh (but also

sakhy), ramya ramma

y assimilates to preceding non-initial v, producing vv bb

Example: divya divva dibba, veditavya veditavva veditabba, bhvya bhavva

bhabba

y and v assimilate to any preceding sibilant, producing ss

Examples: payati passati, yena sena, ava assa, vara issara, kariyati karissati,

tasya tassa, svmin sm

v sometimes assimilates to a preceding stop

Examples: pakva pakka, catvri cattri, sattva satta, dhvaja dhaja

Partial and mutual assimilation

Sanskrit sibilants before a stop assimilate to that stop, and if that stop is not already aspirated, it becomes

aspirated; e.g. c, st, and sp become cch, tth, h and pph

Examples: pact pacch, asti atthi, stava thava, reha seha, aa aha, spara

phassa

In sibilant-stop-liquid sequences, the liquid is assimilated to the preceding consonant, and the cluster behaves like

sibilant-stop sequences; e.g. str and r become tth and h

Examples: stra asta sattha, rra raa raha

Pali

12

t and p become c before s, and the sibilant assimilates to the preceding sound as an aspirate (i.e., the sequences ts

and ps become cch)

Examples: vatsa vaccha, apsaras acchar

A sibilant assimilates to a preceding k as an aspirate (i.e., the sequence k becomes kkh)

Examples: bhiku bhikkhu, knti khanti

Any dental or retroflex stop or nasal followed by y converts to the corresponding palatal sound, and the y

assimilates to this new consonant, i.e. ty, thy, dy, dhy, ny become cc, cch, jj, jjh, ; likewise y becomes .

Nasals preceding a stop that becomes palatal share this change.

Examples: tyajati cyajati cajati, satya sacya sacca, mithy michy micch, vidy

vijy vijj, madhya majhya majjha, anya aya aa, puya puya pua,

vandhya vajhya vajjha vajha

The sequence mr becomes mb, via the epenthesis of a stop between the nasal and liquid, followed by assimilation

of the liquid to the stop and subsequent simplification of the resulting geminate.

Examples: mra ambra amba, tmra tamba

Epenthesis

An epenthetic vowel is sometimes inserted between certain consonant-sequences. As with , the vowel may be a, i,

or u, depending on the influence of a neighboring consonant or of the vowel in the following syllable. i is often

found near i, y, or palatal consonants; u is found near u, v, or labial consonants.

Sequences of stop + nasal are sometimes separated by a or u

Example: ratna ratana, padma paduma (u influenced by labial m)

The sequence sn may become sin initially

Examples: snna sinna, sneha sineha

i may be inserted between a consonant and l

Examples: klea kilesa, glna gilna, mlyati milyati, lghati silghati

An epenthetic vowel may be inserted between an initial sibilant and r

Example: r sir

The sequence ry generally becomes riy (i influenced by following y), but is still treated as a two-consonant

sequence for the purposes of vowel-shortening

Example: rya arya ariya, srya surya suriya, vrya virya viriya

a or i is inserted between r and h

Example: arhati arahati, garh garah, barhi barihisa

There is sporadic epenthesis between other consonant sequences

Examples: caitya cetiya (not cecca), vajra vajira (not vajja)

Pali

13

Other changes

Any Sanskrit sibilant before a nasal becomes a sequence of nasal followed by h, i.e. , sn and sm become h,

nh, and mh

Examples: ta taha, ua uhsa, asmi amhi

The sequence n becomes h, due to assimilation of the n to the preceding palatal sibilant

Example: prana praa paha

The sequences hy and hv undergo metathesis

Examples: jihv jivh, ghya gayha, guhya guyha

h undergoes metathesis with a following nasal

Example: ghti gahti

y is geminated between e and a vowel

Examples: reyas seyya, Maitreya Metteyya

Voiced aspirates such as bh and gh on rare occasions become h

Examples: bhavati hoti, -ebhi -ehi, laghu lahu

Dental and retroflex sounds sporadically change into one another

Examples: jna a (not na), dahati ahati (beside Pali dahati) na nla (not na),

sthna hna (not thna), dukta dukkaa (beside Pali dukkata)

Exceptions

There are several notable exceptions to the rules above; many of them are common Prakrit words rather than

borrowings from Sanskrit.

rya ayya (beside ariya)

guru garu (adj.) (beside guru (n.))

purua purisa (not purusa)

vka ruka rukkha (not vakkha)

Pali writing

Pali alphabet with diacritics

King Ashoka erected a number of pillars with his edicts in at least three regional Prakrit languages in Brahmi

script,

[20]

all of which are quite similar to Pali. Historically, the first written record of the Pali canon is believed to

have been composed in Sri Lanka, based on a prior oral tradition. As per the Mahavamsa (the chronicle of Sri

Lanka), due to a major famine in the country Buddhist monks wrote down the Pali canon during the time of King

Vattagamini in 100 BC. The transmission of written Pali has retained a universal system of alphabetic values, but has

expressed those values in a stunning variety of actual scripts.

In Sri Lanka, Pali texts were recorded in Sinhala script. Other local scripts, most prominently Khmer, Burmese, and

in modern times Thai (since 1893), Devangar and Mon script (Mon State, Myanmar) have been used to record Pali.

Since the 19th century, Pali has also been written in the Roman script. An alternate scheme devised by Frans

Velthuis allows for typing without diacritics using plain ASCII methods, but is arguably less readable than the

standard Rhys Davids system, which uses diacritical marks.

The Pali alphabetical order is as follows:

a i u e o k kh g gh c ch j jh h h t th d dh n p ph b bh m y r l v s h

h, although a single sound, is written with ligature of and h.

Pali

14

Pali transliteration on computers

There are several fonts to use for Pali transliteration. However, older ASCII fonts such as Leedsbit PaliTranslit,

Times_Norman, Times_CSX+, Skt Times, Vri RomanPali CN/CB etc., are not recommendable since they are not

compatible with one another and technically out of date. On the contrary, fonts based on the Unicode standard are

recommended because Unicode seems to be the future for all fonts and also because they are easily portable to one

another.

However, not all Unicode fonts contain the necessary characters. To properly display all the diacritic marks used for

romanized Pali (or for that matter, Sanskrit), a Unicode font must contain the following character ranges:

Basic Latin: U+0000 U+007F

Latin-1 Supplement: U+0080 U+00FF

Latin Extended-A: U+0100 U+017F

Latin Extended-B: U+0180 U+024F

Latin Extended Additional: U+1E00 U+1EFF

Some Unicode fonts freely available for typesetting Romanized Pali are as follows:

Google's Chrome OS has 3 font families which can be downloaded from Google Font Directory

[21]

. Even

better, they can be used as embedded in websites to show the Pali text that users can view without having the

fonts on their machines.

Tinos is a serif font. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

Arimo is a sans-serif font. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

Cousine is a monospaced font. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

The Pali Text Society

[22]

recommends VU-Times

[23]

and Gandhari Unicode

[24]

for Windows and Linux

Computers.

The Tibetan & Himalayan Digital Library

[25]

recommends Times Ext Roman

[26]

, and provides links to

several Unicode diacritic Windows

[27]

and Mac

[28]

fonts usable for typing Pali together with ratings and

installation instructions. It also provides macros

[25]

for typing diacritics in OpenOffice and MS Office.

SIL: International

[29]

provides Charis SIL and Charis SIL Compact

[30]

, Doulos SIL

[31]

, Gentium

[32]

,

Gentium Basic, Gentium Book Basic

[33]

fonts. Of them, Charis SIL, Gentium Basic and Gentium Book Basic

have all 4 styles (regular, italic, bold, bold-italic); so can provide publication quality typesetting.

Libertine Openfont Project

[34]

provides the Linux Libertine font (4 serif styles and many Opentype features)

and Linux Biolinum (4 sans-serif styles) at the Sourceforge

[35]

.

Junicode

[36]

(short for Junius-Unicode) is a Unicode font for medievalists, but it provides all diacritics for

typing Pali. It has 4 styles and some Opentype features such as Old Style for numerals.

Thryomanes

[37]

includes all the Roman-alphabet characters available in Unicode along with a subset of the

most commonly used Greek and Cyrillic characters, and is available in normal, italic, bold, and bold italic.

GUST

[38]

(Polish TeX User Group) provides Latin Modern

[39]

and TeX Gyre

[40]

fonts. Each font has 4

styles, with the former finding most acceptance among the LaTeX users while the latter is a relatively new

family. Of the latter, each typeface in the following families has nearly 1250 glyphs and is available in

PostScript, TeX and OpenType formats.

The TeX Gyre Adventor family of sans serif fonts is based on the URW Gothic L family. The original font,

ITC Avant Garde Gothic, was designed by Herb Lubalin and Tom Carnase in 1970.

The TeX Gyre Bonum family of serif fonts is based on the URW Bookman L family. The original font,

Bookman or Bookman Old Style, was designed by Alexander Phemister in 1860.

The TeX Gyre Chorus is a font based on the URW Chancery L Medium Italic font. The original, ITC Zapf

Chancery, was designed in 1979 by Hermann Zapf.

The TeX Gyre Cursor family of monospace serif fonts is based on the URW Nimbus Mono L family. The

original font, Courier, was designed by Howard G. (Bud) Kettler in 1955.

Pali

15

The TeX Gyre Heros family of sans serif fonts is based on the URW Nimbus Sans L family. The original

font, Helvetica, was designed in 1957 by Max Miedinger.

The TeX Gyre Pagella family of serif fonts is based on the URW Palladio L family. The original font,

Palatino, was designed by Hermann Zapf in the 1940's.

The TeX Gyre Schola family of serif fonts is based on the URW Century Schoolbook L family. The original

font, Century Schoolbook, was designed by Morris Fuller Benton in 1919.

The TeX Gyre Termes family of serif fonts is based on the Nimbus Roman No9 L family. The original font,

Times Roman, was designed by Stanley Morison together with Starling Burgess and Victor Lardent.

John Smith provides IndUni

[41]

Opentype fonts, based upon URW++ fonts. Of them:

IndUni-C is Courier-lookalike;

IndUni-H is Helvetica-lookalike;

IndUni-N is New Century Schoolbook-lookalike;

IndUni-P is Palatino-lookalike;

IndUni-T is Times-lookalike;

IndUni-CMono is Courier-lookalike but monospaced;

An English Buddhist monk titled Bhikkhu Pesala provides some Pali fonts

[42]

he has designed himself. Of

them:

Akkhara is a derivative of Gentium with low profile accents, reduced line-spacing and high accents

prevented from getting clipped. Maths symbols are the same width as figures. The additional arrows,

symbols, and dingbats are designed to match the Caps height.Regular & Italic styles.

Cankama is a Gothic, Black Letter script. Regular style only.

Garava was designed for body text with a generous x-height and economical copyfit. It includes Small

Caps, Bold Small Caps, and Heavy styles besides the usual four styles (regular, italic, bold, bold italic).

Guru is another font family for body text with OpenType features. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic

styles.

Hattha is a hand-writing font. Regular, italic, and bold styles.

Kabala is a distinctive Sans Serif typeface designed for display text or headings. Regular, italic, bold and

bold italic styles.

Lekhana is a Zapf Chancery clone, a flowing script that can be used for correspondence or body text.

Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

Mandala is designed for display text or headings. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

Pali is a clone of Hermann Zapf's Palatino. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

Odana is a calligraphic brush font suitable for headlines, titles, or short texts where a less formal

appearance is wanted. Regular style only.

Talapanna and Talapatta are clones of Goudy Bertham, with decorative gothic capitals and extra ligatures

in the Private Use Area. These two are different only in decorative gothic capitals in the Private Use Area.

Regular and bold styles.

Veluvana is another brush calligraphic font but basic Greek glyphs are taken from Guru. Regular style only.

Verajja is derived from Bitstream Vera. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

VerajjaPDA is a cut-down version of Verajja without symbols. For use on PDA devices. Regular, italic,

bold and bold italic styles.

He also provides some Pali keyboards

[43]

for Windows XP.

The font section

[44]

of Alanwood's Unicode Resources have links to several general purpose fonts that can be

used for Pali typing if they cover the character ranges above.

Some of the latest fonts coming with Windows 7 can also be used to type transliterated Pali: Arial, Calibri, Cambria,

Courier New, Microsoft Sans Serif, Segoe UI, Segoe UI Light, Segoe UI Semibold, Tahoma, and Times New Roman.

Pali

16

And some of them have 4 styles each hence usable in professional typesetting: Arial, Calibri and Segoe UI are

sans-serif fonts, Cambria and Times New Roman are serif fonts and Courier New is a monospace font.

Pali text in ASCII

The Velthuis scheme was originally developed in 1991 by Frans Velthuis for use with his "devnag" Devangar font,

designed for the TeX typesetting system. This system of representing Pali diacritical marks has been used in some

websites and discussion lists. However, as the Web itself and email software slowly evolve towards the Unicode

encoding standard, this system has become almost not necessary and obsolete.

The following table compares various conventional renderings and shortcut key assignments:

character ASCII rendering character name Unicode number key combination HTML code

aa a macron U+0101 Alt+A ā

ii i macron U+012B Alt+I ī

uu u macron U+016B Alt+U ū

.m m dot-under U+1E43 ṁ

.n n dot-under U+1E47 Alt+N ṇ

~n n tilde U+00F1 Alt+Ctrl+N ñ

.t t dot-under U+1E6D Alt+T ṭ

.d d dot-under U+1E0D Alt+D ḍ

"n n dot-over U+1E45 Ctrl+N ṅ

.l l dot-under U+1E37 Alt+L ḷ

References

[1] http:/ / commons. wikimedia. org/ wiki/ Category:Illustrirte_Geschichte_der_Schrift_(Faulmann)

[2] http:/ / commons. wikimedia. org/ wiki/ File:Illustrirte_Geschichte_der_Schrift_(Faulmann)_554. jpg

[3] Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pali Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, page 19.

[4] Students' Britannica India, (http:/ / books.google.com/ books?id=ISFBJarYX7YC& pg=PA145& dq=history+ of+ the+ pali+ language&

sig=ACfU3U2P8niEMFn9ME8litgG1xbStvlmLA#PPA145,M1).

[5] Oberlies, Thomas Pali: A Grammar of the Language of the Theravda Tipiaka, Walter de Gruyter, 2001.

[6] Buddhist India, ch. 9 (http:/ / fsnow.com/ text/ buddhist-india/ chapter9. htm) Retrieved 14 June 2010.

[7] Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pali Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, page 11.

[8] Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pali Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, pages

1-44.

[9] Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pali Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, page 29.

[10] Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pali Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, page 20.

[11] K.R. Norman, Pali Literature. Otto Harrassowitz, 1983, pages 1-7.

[12] Bhikkhu Bodhi, In the Buddha's Words. Wisdom Publications, 2005, page 10.

[13] Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 284

[14] Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 284

[15] Hirakawa, Akira. Groner, Paul. A History of Indian Buddhism: From kyamuni to Early Mahyna. 2007. p. 119

[16] Hirakawa, Akira. Groner, Paul. A History of Indian Buddhism: From kyamuni to Early Mahyna. 2007. p. 119

[17] David Kalupahana, Nagarjuna: The Philosophy of the Middle Way. SUNY Press, 1986, page 19. The author refers specifically to the

thought of early Buddhism here.

[18] Dispeller of Delusion, Pali Text Society, volume II, pages 127f

[19] Robert Caesar Childers, A Dictionary of the Pali Language. Published by Trbner, 1875, pages xii-xiv. Republished by Asian Educational

Services, 1993.

[20] Inscriptions of Asoka by Alexander Cunningham, Eugen Hultzsch. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing. Calcutta:

1877

[21] http:/ / code.google. com/ webfonts

[22] http:/ / www.palitext. com/ subpages/ PC_Unicode.htm

Pali

17

[23] http:/ / zencomp. com/ greatwisdom/ fonts/

[24] http:/ / www.ebmp.org/ p_dwnlds.php

[25] http:/ / www.thlib.org/ tools/ #wiki=/ access/ wiki/ site/ c06fa8cf-c49c-4ebc-007f-482de5382105/ diacritic%20fonts. html

[26] http:/ / www.bcca. org/ services/ fonts/

[27] http:/ / www.thlib.org/ tools/ #wiki=/ access/ wiki/ site/ c06fa8cf-c49c-4ebc-007f-482de5382105/

windows%20unicode%20diacritic%20fonts.html

[28] http:/ / www.thlib.org/ tools/ #wiki=/ access/ wiki/ site/ c06fa8cf-c49c-4ebc-007f-482de5382105/

macintosh%20unicode%20diacritic%20fonts.html

[29] http:/ / www.sil. org/

[30] http:/ / scripts.sil. org/ cms/ scripts/ page.php?site_id=nrsi& id=CharisSIL_download

[31] http:/ / scripts.sil. org/ cms/ scripts/ page.php?site_id=nrsi& cat_id=FontDownloadsDoulos

[32] http:/ / scripts.sil. org/ cms/ scripts/ page.php?site_id=nrsi& item_id=Gentium_download

[33] http:/ / scripts.sil. org/ cms/ scripts/ page.php?site_id=nrsi& item_id=Gentium_basic

[34] http:/ / www.linuxlibertine.org/

[35] http:/ / www.sourceforge. net/ projects/ linuxlibertine

[36] http:/ / junicode. sourceforge. net/

[37] http:/ / www.io. com/ ~hmiller/ lang/

[38] http:/ / www.gust. org.pl/

[39] http:/ / www.gust. org.pl/ projects/ e-foundry/ latin-modern/ download

[40] http:/ / www.gust. org.pl/ projects/ e-foundry/ tex-gyre

[41] http:/ / bombay.indology.info/ software/ fonts/ induni/ index. html

[42] http:/ / aimwell.org/ Fonts/ fonts. html

[43] http:/ / aimwell.org/ Fonts/ Keyboards/ keyboards.html

[44] http:/ / www.alanwood.net/ unicode/ fonts.html

See entries for "Pali" (written by K. R. Norman of the Pali Text Society) and "India--Buddhism" in The Concise

Encyclopedia of Language and Religion, (Sawyer ed.) ISBN 0-08-043167-4

Warder, A.K. (1991). Introduction to Pali (third edition ed.). Pali Text Society. ISBN0860131971.

de Silva, Lily (1994). Pali Primer (first edition ed.). Vipassana Research Institute Publications.

ISBN817414014X.

Mller, Edward (1884,1995). Simplified Grammar of the Pali Language. Asian Educational Services.

ISBN8120611039.

Further reading

Gupta, K. M. (2006). Linguistic approach to meaning in Pali. New Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan. ISBN

81-7574-170-8

Mller, E. (2003). The Pali language: a simplified grammar. Trubner's collection of simplified grammars.

London: Trubner. ISBN 1-84453-001-9

Oberlies, T., & Pischel, R. (2001). Pli: a grammar of the language of the Theravda Tipiaka. Indian philology

and South Asian studies, v. 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016763-8

Hazra, K. L. (1994). Pli language and literature: a systematic survey and historical study. Emerging perceptions

in Buddhist studies, no. 4-5. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld. ISBN 81-246-0004-X

American National Standards Institute. (1979). American National Standard system for the romanization of Lao,

Khmer, and Pali. New York: The Institute.

Russell Webb (ed.) An Analysis of the Pali Canon, Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy; 1975, 1991 (see http:/ /

www. bps. lk/ reference. asp)

Soothill, W. E., & Hodous, L. (1937). A dictionary of Chinese Buddhist terms: with Sanskrit and English

equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali index. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

Collins, Steven (2006). A Pali Grammar for Students. Silkworm Press.

Pali

18

External links

Glenn Wallis, Buddhavacana: A Pali Reader (http:/ / www. pariyatti. org/ Bookstore/ productdetails.

cfm?PC=1924)(Onalaska, Wash: Pariyatti Press, 2011).

Pali Text Society, London. The Pali Text Society's Pali-English dictionary (http:/ / dsal. uchicago. edu/

dictionaries/ pali/ ). Chipstead, 1921-1925.

Buddhist India by T.W. Rhys Davids, chapter IX, Language and Literature (http:/ / fsnow. com/ text/

buddhist-india/ chapter9. htm)

Pali at Ethnologue (http:/ / www. ethnologue. com/ show_language. asp?code=pli)

Pali Text Society (http:/ / www. palitext. com/ )

(http:/ / www. tipitaka. org) Free searchable online database of Pali literature, including the whole Canon

http:/ / pali. pratyeka. org/ Eisel Mazard's excellent website on Pali resources, including

Resources for reading & writing Pli in indigenous scripts: Burmese, Sri Lankan, & Cambodian (http:/ / www.

pratyeka. org/ pali/ )

A textbook to teach yourself Pali (by Narada Thera) (http:/ / www. pratyeka. org/ narada/ )

A reference work on the grammar of the Pali language (by G Duroiselle) (http:/ / www. pratyeka. org/

duroiselle/ )

Complete Pli Canon in romanized Pali and Sinhala, mostly also in English translation (metta.lk) (http:/ / www.

metta. lk/ tipitaka/ )

Pli Canon selection (http:/ / www. accesstoinsight. org/ canon/ index. html)

A guide to learning the Pli language (http:/ / accesstoinsight. org/ lib/ authors/ bullitt/ learningpali. html)

"Pali Primer" by Lily De Silva (requires installation of special fonts) (http:/ / www. vri. dhamma. org/

publications/ pali/ primer/ )

"Pali Primer" by Lily De Silva (UTF-8 encoded) (http:/ / www. saigon. com/ ~anson/ uni/ u-palicb/ e00. htm)

Free/Public-Domain Elementary Pli Course--PDF format (http:/ / www. buddhanet. net/ pdf_file/ ele_pali. pdf)

Free/Public-Domain Pli Course--html format (http:/ / www. orunla. org/ tm/ pali/ htpali/ pcourse. html)

Free/Public-Domain Pli Grammar (in PDF file) (http:/ / www. buddhanet. net/ pdf_file/ paligram. pdf)

Free/Public-Domain Pli Buddhist Dictionary (in PDF file) (http:/ / www. buddhanet. net/ pdf_file/ palidict. pdf)

Comprehensive list of Pli texts on Wikisource (http:/ / wikisource. org/ wiki/ Main_Page:Pali)

Buddhist Dictionary of Pali Proper Names (http:/ / www. metta. lk/ pali-utils/ Pali-Proper-Names/ index. html),

HTML version of the book by G.P. Malalasekera, 1937-8

Pali Text Reader (software) (http:/ / sourceforge. net/ projects/ palireader)

Jain Scriptures (http:/ / www. jainworld. com/ scriptures/ )

Pali help at Help.com Wiki (http:/ / help. com/ wiki/ Pli)

"A Course in the Pali Language," (http:/ / www. bodhimonastery. net/ bm/ programs/ pali-class-online. html)

audio lectures by Bhikkhu Bodhi based on Gair & Karunatilleke (1998).

(http:/ / www. bps. lk/ other_library/ pdf_pali_tables. zip) Pali Conjugation and Declension Tables for Students

(http:/ / www. bps. lk/ other_library/ reference_table_of_pali_literature. pdf) Comprehensive Reference Table of

Pali Literature

Article Sources and Contributors

19

Article Sources and Contributors

Pali Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?oldid=435132578 Contributors: 91okavas, Ahoerstemeier, Alarichus, Andries, Angr, Anupam, Arjun G. Menon, Arvindn, AshLin, Ashinpan,

Asrghasrhiojadrhr, Astral, AxelBoldt, Babajobu, Babbage, Barticus88, Brion VIBBER, Buddhipriya, Byrial, CALR, Calabraxthis, Chameleon, Charles Matthews, ChildersFamily, Chirags,

Circeus, Clasqm, Cmdrjameson, Cminard, Colonies Chris, DaGizza, DabMachine, Danceswithzerglings, Danielscottsmith, DopefishJustin, DuncanHill, Dysprosia, Echalon, Eclecticology,

Ejosse1, El C, Elagatis, Esteban.barahona, Eu.stefan, Eukesh, Fortdj33, GRuban, Gaia2767spm, Gene Nygaard, Gilgamesh, GlassFET, GoonerDP, Grammatical error, Helpsome, Hintha,

Hippopha, Hmains, IceKarma, Ihcoyc, Ikiroid, Imz, Indian Chronicles, Jagged 85, Jaggyjaggy, Jerrykhang, Jfpierce, Jijnasu Yakru, Johnpacklambert, JorisvS, Jpfagerback, Kingsleyj,

Kipholbeck, Koavf, Kripkenstein, Kukkurovaca, Kuldip1, Kwamikagami, Larry Rosenfeld, Le Anh-Huy, Leewonbum, Leglapower, Lerdsuwa, LilHelpa, Lolad321, Loosehenceir, Looxix, Lotus

in the hills, Mahaabaala, Maharaj Devraj, Make, Mandarax, Maqs, Marnen, Martinp23, Mejda, Menchi, Meursault2004, Mhss, Mitsube, Muladeva, Munge, Mxn, NE2, Nat Krause, NathanoNL,

Nichalp, Nikai, Ninly, Ninndthdroad, Nyanatusita, Pamanakara, Pawyilee, Paxsimius, Per Honor et Gloria, Peter jackson, Pineapple fez, Pratyeka, Prosfilaes, Psubhashish, R, RafaAzevedo,

Rama's Arrow, RandomCritic, RandomP, Rasoolpuri, Resurgent insurgent, Rodan44, Ronz, Rosiestep, Rudjek, Rjagha, Sacca, Sacha79, Samuel de mazarin, Sardanaphalus, Shandris,

Shantavira, SimonP, Singhalawap, Sjlain, Spasemunki, Srini81, Ssri1983, Stemonitis, Storkk, Suruena, Sylvain1972, T-W, Tanzeel, Taxman, Tb, Tdudkowski, Tengu800, Thehotelambush,

Tkynerd, Tom Radulovich, Tumblecat, Tuncrypt, Urhixidur, Usedbook, Usingha, Venu62, Verdy p, Vicki Rosenzweig, Vincent Ramos, Vssun, Waltpohl, Wclark, WereSpielChequers,

Wingspeed, Wmahan, Woohookitty, Zerokitsune, RYueli'o, , 255 anonymous edits

Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors

Image:Example.of.complex.text.rendering.svg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Example.of.complex.text.rendering.svg License: Public Domain Contributors: Bayo,

Imz, Waldir, Wereon, 1 anonymous edits

File:Sanskrit-Pali Faulmann Gesch T10.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Sanskrit-Pali_Faulmann_Gesch_T10.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors:

reproduction of ancient documents derivative work: Hmbrger (talk)

License

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

http:/ / creativecommons. org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3. 0/

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Pali - WikipediaDokument98 SeitenPali - Wikipediamathan100% (1)

- Cultural Pali Language in Southeast AsiaDokument62 SeitenCultural Pali Language in Southeast AsiaLê Hoài ThươngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introductiontopr 00 WoolrichDokument248 SeitenIntroductiontopr 00 WoolrichАнтон Коган100% (2)

- A Brief Survey of Sanskrit PDFDokument8 SeitenA Brief Survey of Sanskrit PDFARNAB MAJHINoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review of Scholarship On The Buddhist Councils - PrebishDokument16 SeitenA Review of Scholarship On The Buddhist Councils - Prebish101176Noch keine Bewertungen

- Myanmar The Golden LandDokument13 SeitenMyanmar The Golden Landたつき タイトーNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sects and SectarianismDokument180 SeitenSects and SectarianismnmtuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Encyclopedia of Indian Religions. Springer, Dordrecht: Jbapple@ucalgary - CaDokument17 SeitenEncyclopedia of Indian Religions. Springer, Dordrecht: Jbapple@ucalgary - CazhigpNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparative Analysis of Three Records of The First Buddhist Council From Pāli LiteratureDokument28 SeitenA Comparative Analysis of Three Records of The First Buddhist Council From Pāli Literature101176Noch keine Bewertungen

- 01 Chapter 1Dokument67 Seiten01 Chapter 1mynmrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kaccayana Pali SandhiDokument140 SeitenKaccayana Pali Sandhilxman_thapaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bookofdiscipline 02hornuoftDokument370 SeitenBookofdiscipline 02hornuoftb0bsp4mNoch keine Bewertungen

- BalavataraDokument35 SeitenBalavatarabalabeyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Buddhist Councils at Rajagaha and Vesali As Alleged in Cullavagga XI., XIIDokument80 SeitenThe Buddhist Councils at Rajagaha and Vesali As Alleged in Cullavagga XI., XII101176Noch keine Bewertungen

- Introdution To Pali SandesaDokument10 SeitenIntrodution To Pali SandesaUpUl Kumarasinha100% (1)

- Buddhism in Myanmar PDFDokument14 SeitenBuddhism in Myanmar PDFSukha SnongrotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maharahaniti Review by SarmisthaDokument11 SeitenMaharahaniti Review by Sarmisthaujjwalpali100% (1)

- JinacaritamDokument185 SeitenJinacaritamBudi SetiawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To The Study of East Asian ReligionsDokument5 SeitenIntroduction To The Study of East Asian ReligionsSamPottashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Magadhi The Pure Speech of PDFDokument17 SeitenUnderstanding Magadhi The Pure Speech of PDFHan Sang KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- BasicBuddhism Parâbhava SuttaDokument3 SeitenBasicBuddhism Parâbhava Suttanuwan01Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Book IIVon EverandThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Book IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa - A Comparative StudyDokument5 SeitenDipavamsa and Mahavamsa - A Comparative Studyshu_sNoch keine Bewertungen

- U Hla Myint Pali Textbook2Dokument101 SeitenU Hla Myint Pali Textbook2Evgeny Bobryashov0% (1)

- Faith in Early Buddhism JIPDokument21 SeitenFaith in Early Buddhism JIPvasubandhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buddhist Calendar Ritual in MyanmarDokument47 SeitenBuddhist Calendar Ritual in Myanmarshu_s100% (1)

- Chakravarti Uma Social Dimensions of Early Buddhism 249p PDFDokument251 SeitenChakravarti Uma Social Dimensions of Early Buddhism 249p PDFbhasmakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meditation HindiDokument2 SeitenMeditation Hindidhammamaster100% (2)

- 30.8 Upaya Skillful Means. Piya PDFDokument53 Seiten30.8 Upaya Skillful Means. Piya PDFpushinluck100% (1)

- Pali DhatupathaDokument94 SeitenPali DhatupathaSonam GyatsoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pali TextbookDokument51 SeitenPali TextbookThanh TâmNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Six Buddhist Councils - LTYDokument5 SeitenThe Six Buddhist Councils - LTYWan Sek ChoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 An Introduction To The Brahma, Jāla Sutta: The Discourse On The Perfect NetDokument21 Seiten1 An Introduction To The Brahma, Jāla Sutta: The Discourse On The Perfect NetujjwalpaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mulamadhyamakakarika Abbreviations Merged 1 483Dokument483 SeitenMulamadhyamakakarika Abbreviations Merged 1 483leeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary Derivatives (Taddhita) : Format: Noun Stems + Suffix Noun StemDokument9 SeitenSecondary Derivatives (Taddhita) : Format: Noun Stems + Suffix Noun StemAshin UttamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Traditional - Tools in Pali Grammar Relational Grammar and Thematic Units - U Pandita BurmaDokument31 SeitenTraditional - Tools in Pali Grammar Relational Grammar and Thematic Units - U Pandita BurmaMedi NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Were Upagupta and His AsokaDokument24 SeitenWho Were Upagupta and His AsokaJigdrel770% (1)

- ABHIDHARMA Term Paper KargesDokument9 SeitenABHIDHARMA Term Paper KargesHardie Karges100% (1)

- Colossal Buddha Images of Ancient Sri LankaDokument3 SeitenColossal Buddha Images of Ancient Sri Lankashu_sNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Drewes - Revisiting The Phrase 'Sa Prthivīpradeśaś Caityabhūto Bhavet' and The Mahāyāna Cult of The BookDokument43 SeitenDavid Drewes - Revisiting The Phrase 'Sa Prthivīpradeśaś Caityabhūto Bhavet' and The Mahāyāna Cult of The BookDhira_Noch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Newar StudiesDokument84 SeitenJournal of Newar StudiesAmik TuladharNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of LahoulDokument43 SeitenHistory of Lahoulapi-37205500% (1)

- Relig Third Year AllDokument218 SeitenRelig Third Year AllDanuma GyiNoch keine Bewertungen

- DharmakirtiDokument2 SeitenDharmakirtiWayneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patthanudesa Dipani (Commentary On Causality)Dokument42 SeitenPatthanudesa Dipani (Commentary On Causality)Tisarana ViharaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal 188200 Pa Liu of TDokument74 SeitenJournal 188200 Pa Liu of TPmsakda Hemthep100% (2)

- Pali ProsodyDokument53 SeitenPali ProsodymehdullaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taxila - An Ancient Indian University by DR S. Srikanta Sastri PDFDokument3 SeitenTaxila - An Ancient Indian University by DR S. Srikanta Sastri PDFSaurabh Surana100% (1)

- Group 8 Silahis, Diana Rose Princess Gadiano, Mary-Ann Meña, AljhunDokument13 SeitenGroup 8 Silahis, Diana Rose Princess Gadiano, Mary-Ann Meña, AljhunPrincessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abhidharma - Class Notes (Intro)Dokument10 SeitenAbhidharma - Class Notes (Intro)empty2418Noch keine Bewertungen

- Salomon 2021. New Biographies of The Buddha in GāndhārīDokument24 SeitenSalomon 2021. New Biographies of The Buddha in GāndhārīRuixuan ChenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buddhist Scriptures First Rehearsal of The TipitakaDokument2 SeitenBuddhist Scriptures First Rehearsal of The Tipitakareader1453Noch keine Bewertungen

- MeritDokument16 SeitenMeritmichaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bodhisattvas and Buddhas Early Buddhist Images From MathurāDokument37 SeitenBodhisattvas and Buddhas Early Buddhist Images From MathurāСафарали ШомахмадовNoch keine Bewertungen

- Udanavarga English PreviewDokument27 SeitenUdanavarga English PreviewLuis Jesús Galaz CalderónNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pali LanguageDokument8 SeitenThe Pali LanguagepriyasensinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sanskrit IntroductionDokument19 SeitenSanskrit Introductionzxcv2010Noch keine Bewertungen

- Talk Edit View History: Article ReadDokument10 SeitenTalk Edit View History: Article Readashish.nairNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Pali Language-A Little HistoryDokument11 SeitenWhat Is Pali Language-A Little HistoryViên AnNoch keine Bewertungen

- LeishmaniaDokument10 SeitenLeishmaniaPatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dang San Ngou Nie - GdpiDokument167 SeitenDang San Ngou Nie - GdpiPatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infographics 3 Interest RateDokument6 SeitenInfographics 3 Interest RatePatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Review-Essay BelloDokument8 Seiten7 Review-Essay BelloPatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liberty of Contract: Yale Law JournalDokument34 SeitenLiberty of Contract: Yale Law JournalPatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microsoft PowerPoint Cardiology Made EasyDokument71 SeitenMicrosoft PowerPoint Cardiology Made EasyPatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Service PDFDokument296 SeitenCustomer Service PDFPatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glossary of Italian-English (Salesian)Dokument12 SeitenGlossary of Italian-English (Salesian)Patrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Free Complete Pali ScripturesDokument1 SeiteFree Complete Pali ScripturesPatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Xi - of CrueltyDokument3 SeitenChapter Xi - of CrueltyPatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beninca GeorgetownDokument40 SeitenBeninca GeorgetownPatrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ben Inca 2004Dokument55 SeitenBen Inca 2004Patrick CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design and Fabrication of Light Electric VehicleDokument14 SeitenDesign and Fabrication of Light Electric VehicleAshish NegiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 Ford Fiesta 1.6l Sohc Fluid CapacitiesDokument1 Seite2013 Ford Fiesta 1.6l Sohc Fluid CapacitiesRubenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3250-008 Foundations of Data Science Course Outline - Spring 2018Dokument6 Seiten3250-008 Foundations of Data Science Course Outline - Spring 2018vaneetNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08 - Chapter 1Dokument48 Seiten08 - Chapter 1danfm97Noch keine Bewertungen

- Symbolic Interaction Theory: Nilgun Aksan, Buket Kısac, Mufit Aydın, Sumeyra DemirbukenDokument3 SeitenSymbolic Interaction Theory: Nilgun Aksan, Buket Kısac, Mufit Aydın, Sumeyra DemirbukenIgor Dutra BaptistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Siemens 6SL31622AA000AA0 CatalogDokument20 SeitenSiemens 6SL31622AA000AA0 CatalogIrfan NurdiansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- FS1 Worksheet Topic 6Dokument2 SeitenFS1 Worksheet Topic 6ALMALYN ANDIHNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1973 Essays On The Sources For Chinese History CanberraDokument392 Seiten1973 Essays On The Sources For Chinese History CanberraChanna LiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal Try Out Ujian NasionalDokument9 SeitenSoal Try Out Ujian NasionalAgung MartaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demystifying The Diagnosis and Classification of Lymphoma - Gabriel C. Caponetti, Adam BaggDokument6 SeitenDemystifying The Diagnosis and Classification of Lymphoma - Gabriel C. Caponetti, Adam BaggEddie CaptainNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Goldfish and Its Culture. Mulertt PDFDokument190 SeitenThe Goldfish and Its Culture. Mulertt PDFjr2010peruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume Pet A Sol LanderDokument3 SeitenResume Pet A Sol LanderdreyesfinuliarNoch keine Bewertungen

- HimediaDokument2 SeitenHimediaWiwit MarianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Empowerment TechnologyDokument2 SeitenEmpowerment TechnologyRegina Mambaje Alferez100% (1)

- Boomer L2 D - 9851 2586 01Dokument4 SeitenBoomer L2 D - 9851 2586 01Pablo Luis Pérez PostigoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care Plan Diabetes Mellitus Type 1Dokument2 SeitenNursing Care Plan Diabetes Mellitus Type 1deric85% (46)

- KITZ - Cast Iron - 125FCL&125FCYDokument2 SeitenKITZ - Cast Iron - 125FCL&125FCYdanang hadi saputroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sabre V8Dokument16 SeitenSabre V8stefan.vince536Noch keine Bewertungen

- HC-97G FactsheetDokument1 SeiteHC-97G FactsheettylerturpinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sagan WaltzDokument14 SeitenSagan WaltzKathleen RoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Circuit Breaker - Ground & Test Device Type VR Electrically OperatedDokument24 SeitenCircuit Breaker - Ground & Test Device Type VR Electrically OperatedcadtilNoch keine Bewertungen

- PmtsDokument46 SeitenPmtsDhiraj ZanzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kyoto Seika UniversityDokument27 SeitenKyoto Seika UniversityMalvinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report Palazzetto Croci SpreadsDokument73 SeitenReport Palazzetto Croci SpreadsUntaru EduardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Five Star Env Audit Specification Amp Pre Audit ChecklistDokument20 SeitenFive Star Env Audit Specification Amp Pre Audit ChecklistMazhar ShaikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMST 398 SyllabusDokument7 SeitenAMST 398 SyllabusNatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1 Learning PrinciplesDokument2 SeitenModule 1 Learning PrinciplesAngela Agonos100% (1)

- Culture Performance and Economic Return of Brown ShrimpDokument8 SeitenCulture Performance and Economic Return of Brown ShrimpLuã OliveiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ostrich RacingDokument4 SeitenOstrich RacingalexmadoareNoch keine Bewertungen

- FinancialAccountingTally PDFDokument1 SeiteFinancialAccountingTally PDFGurjot Singh RihalNoch keine Bewertungen