Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Logistics Lifecycle Within The Product Lifecycle

Hochgeladen von

Tuan NguyenCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Logistics Lifecycle Within The Product Lifecycle

Hochgeladen von

Tuan NguyenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

60 LOGISTICS INFORMATION MANAGEMENT 3,3

M

ore attention needs to be focused on

logistics elements at the planning stage

off a product so that during and at the

end off a product's l i fe costs can be minimised

or avoided altogether.

The Logistics

l i f e Cycle of

a Product

Paul Ryan

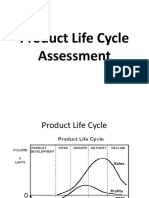

Product Life Cycle

A product life cycle concept is used as a convenient way

in which to display graphically the contribution value of

a product over time.

The product life cycle is normally represented in marketing

texts as having five stages. These are usually entitled:

(1) Development

(2) Growth

(3) Maturity

(4) Saturation

(5) Decline.

Figure 1 shows the normal representation of these market

stages. Notice that there is a conscious lack of detail about

the decline phase. It is assumed that from somewhere

within the company will emerge profit to sustain the

company's existence. As far as a specific product is

concerned, it is as if some lower level immortality is

expected or hoped for by the originators of the product.

The fact that the product will, in all probability, reach a

decline stage is reluctantly accepted. History shows that

a high proportion of products launched do in fact fail within

a reasonably short period of time. It is therefore very

important to incorporate the decline phase in the expected

marketing plan for any product. It is more important today

due to the impact of competition, substitution and

deregulation.

The decline phase can be an expected and planned for

occurrence. The product life-cycle time can be short, as

in "fad" products. It can be long, as in some basic products

such as washing powder. However, significant new

investments in any aspect required to change something

about the product might be good reason to reappraise the

logistics life cycle. Adding in new elements, and allowing

for old elements, will help to keep the effects of the changes

visible for the benefit of all those involved in the system.

The decline phase can occur prematurely when a product

fails for any reason. The risk of failure has always been

high. This risk of failure is a prime reason for having

potential decline phase costs estimated and included as part

of the marketing proposal. In this way, a firm can take an

overview of the risk exposure across its portfolio of

products for each of the businesses it is in.

The logistics life-cycle graph stages also become a useful

framework to use to categorise and display investment cost

risks, physical factors and information systems needs.

Product managers and marketing managers must have

optimism. This is what makes the commercial world go

round. It is normal for all the effort and emphasis to be

placed on the exciting prospects for the product. Marketers

accept all the costs involved in the birth and launching of

a product. However, the cost of getting out of a product

is often overlooked. At the end of a product life cycle the

costs involved are frequently seen as being the concern

of other functions, such as production and warehousing.

Whatever the function, the costs reside in the organisation.

The end of the product life is perhaps perceived as a rather

gloomy result and one into which it is understandable that

effort and in fact exposure is avoided.

Marketing is often described as being concerned with the

four "Ps": product, price, promotion and place. The

logistics life-cycle concept concerns the "place" function

from procurement, through processing to consumption and

eventual disposal.

THE LOGISTICS LIFE CYCLE OF A PRODUCT 61

The Place Function

This often appears to be the least interesting of the four

"Ps" to marketers. As a result the elements involved may

get the least concentration of effort. Yet the risks and costs

involved are high and the potential savings which can result

from effective management of the elements are significant.

Marketing texts often comment that the "place" function

requires the executive to determine the channel(s) for

distributing the product. Such channels may include:

direct to end customer

via a wholesaler to retailer

to retailers' central warehouses

through selling agents to retailers

through the firm's own retail outlets

and others which are constantly evolving.

Frequently the historic pattern of the firm's present product

distribution system will dominate the choice of distribution

path for a new product. This may be one reason why

marketing staff are often not forced into making clear

decisions on the effects of new products on the distribution

system. The channel is simply thought to be able to cater

for whatever increasing volume and range of products may

be presented to it.

Channel decisions require more consideration as New

Zealand society changes. The deregulated environment is

providing many options not previously available. Consider,

for example, the channel decisions available for cosmetics.

One leading brand may ship in pallet lots to other

distributors where quantities are split and small lots

distributed to retailers. Another brand sends out an average

size of four kilo parcels to direct sales agents. The same

product but with quite different channel implications. Milk

distribution is an example of the dramatic changes occurring

in the use of distribution channels.

Often this decision, involving the "channel", goes no

further than getting the product onto retailers' shelves. But

awareness by consumers of the possible effects of the

product on users has increased. Tamperproof sealing,

colour additions, nutritional content, irritants in fabrics, and

service cost considerations, are examples of additional

marketing requirements being increasingly sought by

consumers over the last few years.

Disposal of the by-products, packaging and so on, is likely

to become increasingly an on-going cost pressure for

marketers. Agencies in New Zealand, as around the world,

are pushing for manufacturers to be levied on packaging

use in order to fund community waste disposal. Bio-

degradable packaging is being sought. We see a wide variety

of packaging with metallised film and plastic non-returnable

containers of many different forms emerging into the

product and the rubbish stream. Gas flushing to preserve

freshness is a new growth area. The process of irradiation

of food has created a high profile antagonistic consumer

group. Such packaging may be cost effective in presenting

the desired product image and may have advantages in

protecting the product and enhancing its life. If they have

not already done so, those responsible for the marketing

of products must start considering these logistics aspects

in their marketing plans at a very early stage.

Finally, what about the physical aspects remaining when

the product is changed or taken from the market? That

blank space at the end of the product life cycle! This will

include raw materials, packaging, possibly specialised

machinery capacity, factory space, if not to be used for

other purposes, finished stock and any additional cost of

moving products through the channels to final consumers.

Even a change of packaging can create large cost

implications down the channel.

It is suggested that a logistics life-cycle system should be

used to complement the traditional marketing life-cycle used

in product marketing plans. In this way marketers can be

prompted to complete their marketing plans and make

allowance for the costs of the "end game" for each product

in their portfolio.

The Logistics Li fe Cycle

Figure 2 shows a more complete view of a product life cycle

net revenue graph. The cycle is extended to show clearly

the birth and death of the product. The definition of a

"product" for the purpose of utilising a logistics life-cycle

approach is open to individual interpretation. It could be

a sole stock keeping unit (SKU), a product range or a signif-

icant change to a stable long-life product. The firm not only

needs to know the cost of getting into the product but also

the cost of getting out of it at the various stages of the

life cycle.

Let us further examine each of the life cycle segments.

Concept/Design

Some costs are incurred which may or may not be

attributable to a specific product. Where possible it may

be helpful to include these. For products such as

pharmaceuticals or hi-tech products, aerospace, etc., the

segment will be very high. The scale of the costs will

determine whether or not it is an important category.

62 LOGISTICS INFORMATION MANAGEMENT 3,3

Table I.

Examples of Logistics Elements Which May Require Specialist Input

High tech.

specialist

Low tech.

mass market

Logistics Life Cycle Stages

Concept

Design

Channels

consideration

Physical

handling

Any

perceived

limits

Research

Confirmation

Mechanical

simplicity

servicing

Transporting

Health

Environmental

Disposal

(waste)

Disposal

(end of life-

cycle)

Unitisation

Production

Prelaunch

Spares

availability

Information

systems

needs

Product

recall

plan

Inventory

level

and

location

Customer

service

levels

Deployment

Support

services

audit

Customer

service

performance

Special

inventory

needs

Information

systems

performance

Environmental

and health

reactions

Maturity

Logistics

systems

cost and

capital

control

Customer

services

review

Inventory

review

Decline

Spares

capital

reduction

Labour

cost

reduction

Customer

service

review

Inventory

review

Disposal

Labour

contracts

spares

servicing

Inventory:

finished

goods

raw

materials

work in

progress

packaging

channel

stock

Information

systems

withdrawal

Consumer

reaction

Channel reaction

Research/Confirmation

Again the scale will determine the need to include these

costs. Many products will start incurring significant market

research costs at this point. The cost of assembling capital

justification where significant investment is required may

also be substantial. Table I shows some of the logistics

factors which should now start entering into the draft

marketing plans. These logistics elements usually involve

physical aspects of the proposed product. It is suggested

that such a table can provide a prompt for marketing staff to

call in expertise at this early stage of the product. The aim

is to obtain as wide a view of some of the special physical

aspects before further substantial expenditure is incurred.

Production Prelaunch

The investment in raw materials, packaging, production

equipment and buildings, trading and financial analysis may

be substantial by this stage. Here we see the peak of the

costs being ploughed in prior to any revenue being earned

by this product to offset these costs.

In Table I we see the necessity to consider the effects that

introducing this product will have on the physical systems

of the company and its chosen distribution channel. For

example, does the company have a product recall plan and

is this plan suitable for this product? Are the information

systems going to provide the right sort of information for

the product to be managed through the distribution

channels? Will customer service be measurable?

Are those people involved in the inventory and production

planning properly trained? Do they have the right objectives

to ensure that the expected demand or variation about the

mean demand has plans available that are appropriate?

Deployment

In this segment positive revenue is expected. However,

it is often offset by a heavy investment in launch processes

such as advertising, sampling and trade functions. Such

expenses can reduce the net profit to a low level from quite

high sales revenue during the early stages.

It is at this time that the information systems and logistics

support systems should be audited. Is the customer service

that the marketer wanted in place? Are the information

systems delivering the vital sales and customer information

needed for hands-on management of the product? Have

any unexpected environmental, handling or health situations

occurred? It is vital that the systems are in place during

the deployment stage to ensure that the future management

of the product is well controlled. This information will be

the database from which sensitive marketing decisions can

be made.

Maturity

This is the segment where dreams come true ... and

some come crashing down. In this segment, revenue must

exceed present costs and supply margins sufficient to cover

the costs incurred in the previous segments plus a profit

THE LOGISTICS LIFE CYCLE OF A PRODUCT 63

margin. It is hoped that this euphoric state will last a long

time. Unfortunately product life cycle times are shrinking.

Global competition and the consumer demand for choice

and change are compressing product life cycles. This fact

emphasises the importance of adopting a more critical view

of the whole life cycle. Marketing managers must ensure

that all costs of the product will be taken into account, so

that a true and fair view of the expected net results can

be seen. It would be wise during the mature stage of the

product to review regularly the decline and disposal stages.

Determine whether the costs expected when these positions

are reached are appropriate to the volumes being

experienced during the mature stage. Ensure that proper

plans are available in order to guide all of the separate

function managers in the organisation.

Decline

For whatever reason, the product revenues less costs start

to decline. This is a time when marketing staff must bring

out the "end game" plan developed and honed during the

mature stage. What are the full costs of getting out of this

product? They include raw materials, packaging, plant

utilisation, staff to put off at a cost, finished goods stock,

contracts within the distribution channel, any returned

product costs risks.

Disposal

Having an "end game" plan means that the marketer will

be able to determine that point in the net profit graph at

which the decision to terminate the product has already been

made. Making the plan beforehand ensures that the decision

is clean and business-like. If no plans are in hand then the

decision often becomes difficult. Inter-function performances

in the company may emerge. Why should the production

manager have to write off packaging or get sub-optimal use

of his plant for a marketing decision? How can the warehouse

manager utilise his space, vehicles and staff now that

marketing have terminated a product? If these costs are

taken up in the marketing plan, then this type of inter-

function resistance is avoided. If these other functional

executives are aware of the "end game" plan then they will

have been running their operations in a manner able to

encompass the disposal stage. The marketing manager can

make the decision knowing that he is responsible for the

results right through the product life cycle. The costs of

the disposal stage are built in, together with the naming

and the coming of age. Table I provides some indicative

headings that could be included in the disposal phase of a

product marketing plan.

Logistic Considerations t o be Bui l t i nto

Mar ket i ng Life-cycle Pl anni ng

Products that Need After Sales Service

Has the product been engineered to be suitable for servicing

or is it a disposable item? Is it to be serviced? Are spares

required? Who will do the servicing? Has the service

network been set up? Has training been planned? Is feedback

arranged?

Products that Might Raise Environmental Reactions

Is the packaging going to create an added volume to waste

disposal? Is it a new packaging form which might excite a

special interest group? How is disposal to be managed? Are

there instructions on the pack? Are warnings necessary?

Is the company seen to be actively involved?

Products which might be Accused of being Health Risks

Is evidence to the contrary available? What is the risk of

withdrawal, consumer damage suits, etc., present or future

discoveries? Are all handling methods right from production

to final environmentally-acceptable disposal, documented

and proven? Are all those who will contact the product in

possession of the necessary information and training to

ensure absolute conformity to laid down safety standards?

Product Return or Recall

Are documented procedures available and do all people in

the right channel distribution through to the customers

know what to do to:

(1) protect the public and

(2) protect the company from extravagant actions?

The cost of returning products against the normal flow in the

distribution channel is very high. Estimates suggest at least

nine times the cost of the normal flow. Each company should

have written plans for various levels of concern. Progres-

sively higher echelons of management are involved depending

upon the indicated scale of severity of the problem.

Conclusion

Marketing managers need to focus attention on logistics

elements during and at the end of a product's life. This may

be in the generic sense or for the specific stock-keeping

unit (SKU). By doing so the marketer aims to avoid or

minimise costs which may occur through physical aspects

of the product and its surrounding physical environment.

Major examples of the costs of getting out of products can

be seen in New Zealand now. The decline phase of the

carcass meat industry is well known and should be sufficient

for a shock reaction. The life cycle of many New Zealand

products has been shortened with deregulation. The costs

of the disposal phase of getting out of these products can

be seen as a considerable burden to those companies and

possibly to the communities in which they aire situated. The

inclusion of a logistics perspective at the planning stage of

a product, or a significant change to an existing product is

now a necessity. A review of the logistics element should

be undertaken at least annually, or when significant changes

occur.

A plan of action for the decline phase of products has become

an imperative in today's marketplace. The use of this

technique will improve the marketer's ability to control and

optimise the bottom line results of the firm. It will expose

risks at an early stage and allow them to be quantified to

enhance decision quality. Improved inter-functional

relationships will occur resulting in an enhancement of the

professionalism of marketing.

Paul Ryan is General Manager of General Foods Distribution in Auckland, New Zealand.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Project Planning and ManagementDokument25 SeitenProject Planning and ManagementTt OwnsqqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation-Military Ship Life Cycle Cost (LCC) ModelDokument34 SeitenPresentation-Military Ship Life Cycle Cost (LCC) ModelMarcelo De Oliveira PredesNoch keine Bewertungen

- General BCG-Ansoff's MatrixDokument4 SeitenGeneral BCG-Ansoff's Matrixtotti_sNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design and Analysis of Vertical Axis Wind Turbine With Multi-Stage GeneratorDokument4 SeitenDesign and Analysis of Vertical Axis Wind Turbine With Multi-Stage GeneratorInternational Journal of Innovations in Engineering and ScienceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vulcan Seals Mechanical Seal BrochureDokument148 SeitenVulcan Seals Mechanical Seal BrochureFidari Pump PartsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multi-Project Planning in ShipbuildingDokument17 SeitenMulti-Project Planning in ShipbuildingSADATHAGHINoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 48 - Report 01Dokument10 SeitenUnit 48 - Report 01Yashodha HansamalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 141 Digital Ship 2020-02&03Dokument50 Seiten141 Digital Ship 2020-02&03Konstantinos KoutsourakisNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICCAS BreakdownStructuresThroughLifecycleStagesDokument15 SeitenICCAS BreakdownStructuresThroughLifecycleStagesJoey Zamir Huerta MamaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design Exploration - Judd KaiserDokument30 SeitenDesign Exploration - Judd KaiserSangbum KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Shipyard's Management SystemDokument7 Seiten7 Shipyard's Management Systemryan310393Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gear Box ReportDokument39 SeitenGear Box ReportNisar HussainNoch keine Bewertungen

- SWBS ArtículoDokument10 SeitenSWBS ArtículoSandra Paola TeranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smart Logistics May 2012Dokument68 SeitenSmart Logistics May 2012saldivaroswaldoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 CostFact Public PDFDokument45 Seiten6 CostFact Public PDFSeptiyan Adi NugrohoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ME374 Module 4Dokument22 SeitenME374 Module 4Christian Breth BurgosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maxwell v16 L01 IntroductionDokument31 SeitenMaxwell v16 L01 IntroductionCasualKillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preview of Road and Off Road Vehicle System Dynamics HandbookDokument2 SeitenPreview of Road and Off Road Vehicle System Dynamics HandbookFiorenzo TassottiNoch keine Bewertungen

- IDP Guidance and Sample IDPDokument9 SeitenIDP Guidance and Sample IDPRodrigo MoraesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preview Steffen Bangsow Auth. Tecnomatix Plant Simulation Modeling and Programming by Means of ExamplesDokument20 SeitenPreview Steffen Bangsow Auth. Tecnomatix Plant Simulation Modeling and Programming by Means of Examplesaakhyar_2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Production StrategyDokument14 SeitenProduction StrategyJD_04100% (3)

- Ship Electrical Load Analysis and Power Generation Optimisation To Reduce Operational CostsDokument7 SeitenShip Electrical Load Analysis and Power Generation Optimisation To Reduce Operational CostsmahmudNoch keine Bewertungen

- English For Teachers 11 PDED 0021/DED 0321: Oral Presentation SkillsDokument30 SeitenEnglish For Teachers 11 PDED 0021/DED 0321: Oral Presentation SkillsMzee MsideeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mckinsey 7s Leadership StyleDokument2 SeitenMckinsey 7s Leadership StyleLee YouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engine Performance AnalysisDokument11 SeitenEngine Performance AnalysissushmarajagopalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrical MotorDokument30 SeitenElectrical Motordayat_ridersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ansys Advantage Digital Exploration Aa V11 I2Dokument60 SeitenAnsys Advantage Digital Exploration Aa V11 I2david_valdez_83Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mintzberg 5 P'sDokument9 SeitenMintzberg 5 P'sVivek SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Free PPT Templates: Insert The Subtitle of Your PresentationDokument48 SeitenFree PPT Templates: Insert The Subtitle of Your PresentationPrudhvi BethamcherlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrician NSQF 04082015Dokument263 SeitenElectrician NSQF 04082015naymanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Information Value ChainDokument47 SeitenInformation Value ChainChowdhury Golam Kibria100% (1)

- Resume and Cover LetterDokument3 SeitenResume and Cover LetterJesse Caudle100% (1)

- 9.4 - Project Planning Execution (Chart)Dokument1 Seite9.4 - Project Planning Execution (Chart)Salman Rao0% (1)

- Insight ProfileDokument23 SeitenInsight Profilesee1tearNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction of Smart Power Module: For Low-Power Motor Drives ApplicationsDokument27 SeitenIntroduction of Smart Power Module: For Low-Power Motor Drives ApplicationsChristian AztecaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LNB 30103 Shipbuilding Technology: PROJECT 2-150m Feeder Ship CargoDokument42 SeitenLNB 30103 Shipbuilding Technology: PROJECT 2-150m Feeder Ship CargoIzzuddin Izzat100% (1)

- 11 Oscillating Water ColumnDokument8 Seiten11 Oscillating Water ColumnFernandoMartínIranzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 05 Problem & Objective TreeDokument18 Seiten05 Problem & Objective TreeJosep PeterNoch keine Bewertungen

- LID ICT Assessment - BSBSMB407 Manage A Small Team Sem1 - 2020Dokument7 SeitenLID ICT Assessment - BSBSMB407 Manage A Small Team Sem1 - 2020aliNoch keine Bewertungen

- BizplanbDokument390 SeitenBizplanbMuhands JoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ayoola CVDokument3 SeitenAyoola CVAyoola AyodejiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap013 Target Costing Cost MNGTDokument49 SeitenChap013 Target Costing Cost MNGTSyifaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technicalguidebook 1 10 en ReveDokument446 SeitenTechnicalguidebook 1 10 en RevetheerawsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Automation Studio E7 Automotive en HighDokument8 SeitenAutomation Studio E7 Automotive en HighquoctuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class - 1&2 IntroductionDokument33 SeitenClass - 1&2 IntroductionharinaathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Product Life Cycle ManagementDokument58 SeitenProduct Life Cycle Managementcaptain mkNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04 Preliminary Design Document PDFDokument5 Seiten04 Preliminary Design Document PDFSakali AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Funnel Left 4levelsDokument1 SeiteFunnel Left 4levelssuryaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vehicle Layout Transmission SystemsDokument38 SeitenVehicle Layout Transmission SystemsKhan Liyaqat100% (1)

- Training and Development Project JUSCO Sec B Group No.9Dokument23 SeitenTraining and Development Project JUSCO Sec B Group No.9Kalyani Singh100% (1)

- Arne Schuldt - Multiagent Coordination Enabling Autonomous LogisticsDokument284 SeitenArne Schuldt - Multiagent Coordination Enabling Autonomous LogisticsLeandru5Noch keine Bewertungen

- Personal EffectivenessDokument14 SeitenPersonal EffectivenessGillian Tan IlaganNoch keine Bewertungen

- gb5085 - Internship ReportDokument13 Seitengb5085 - Internship ReportTobi KaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nshud A, A: Mahmudul HasanDokument1 SeiteNshud A, A: Mahmudul HasanMahmudul HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write A Technical ProposalDokument7 SeitenHow To Write A Technical ProposalMotasem AlMobayyed100% (1)

- TSP in Excel PDFDokument23 SeitenTSP in Excel PDFJuank Z BkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Product Life CycleDokument5 SeitenProduct Life CycleCarbon Nano TubeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bab 11Dokument8 SeitenBab 11Gloria AngeliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SM Manual 09 Market Life Cycle Model Etc.Dokument7 SeitenSM Manual 09 Market Life Cycle Model Etc.Ravi KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 01 22 JNJ Earning ReportDokument2 Seiten2019 01 22 JNJ Earning ReportTuan NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABT Abbott Laboratories: Health Care Equipment & Services Health Care EquipmentDokument2 SeitenABT Abbott Laboratories: Health Care Equipment & Services Health Care EquipmentTuan NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- IBM International Business Machines Corporation: $21.76 Billion, vs. $21.71 Billion As Expected by AnalystsDokument2 SeitenIBM International Business Machines Corporation: $21.76 Billion, vs. $21.71 Billion As Expected by AnalystsTuan NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Earnings Call CalendarDokument25 SeitenEarnings Call CalendarTuan NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- LogDokument7 SeitenLograjbirprince3265Noch keine Bewertungen

- SCM in A NutshellDokument2 SeitenSCM in A NutshellTuan NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meditech SurgicalDokument6 SeitenMeditech SurgicalTuan NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tesco's KPIDokument10 SeitenTesco's KPIHuy BachNoch keine Bewertungen

- East Asia Institute of Management: E-Commerce With LogisticsDokument14 SeitenEast Asia Institute of Management: E-Commerce With LogisticsTuan NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- GM Packing Specification PDFDokument3 SeitenGM Packing Specification PDFazb00178Noch keine Bewertungen

- Banana PadsDokument14 SeitenBanana PadsSunny RajopadhyayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guide Line For Contract ManufacturingDokument10 SeitenGuide Line For Contract ManufacturingAkib MurshedNoch keine Bewertungen

- TW316 PresentationDokument26 SeitenTW316 PresentationCherylNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whos Who in Logisitcs International 2010Dokument625 SeitenWhos Who in Logisitcs International 2010klokenziNoch keine Bewertungen

- Material PropertiesDokument3 SeitenMaterial PropertiesmialitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eastern Research Group StudyDokument147 SeitenEastern Research Group Studynews21100% (1)

- Pepsico Annual Report 2021: Form 10-K (Nasdaq:Pep)Dokument11 SeitenPepsico Annual Report 2021: Form 10-K (Nasdaq:Pep)Nguyễn Minh NghiêmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ampacet Extends Clarifier and Antistat Ranges PDFDokument2 SeitenAmpacet Extends Clarifier and Antistat Ranges PDFXuân Giang NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Food SCP Circular Economy Report Feb 2018Dokument32 SeitenFood SCP Circular Economy Report Feb 2018Otres100% (1)

- Aachi Masala Case StudyDokument7 SeitenAachi Masala Case StudySHRUTI VNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creamery Juice HACCP PlanDokument27 SeitenCreamery Juice HACCP PlanDavid ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technical Information Sheet: BD Microtainer® Blood Collection Tube Extender (Accessory)Dokument2 SeitenTechnical Information Sheet: BD Microtainer® Blood Collection Tube Extender (Accessory)Sonia TsamoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ism ch11 Answers To The Questions at The End of The Chapters Including The Case StudiesDokument8 SeitenIsm ch11 Answers To The Questions at The End of The Chapters Including The Case StudiesThuraMinSweNoch keine Bewertungen

- Food, Beverage, Oil Glass Bottle CatalogDokument16 SeitenFood, Beverage, Oil Glass Bottle CatalogJigar KapasiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budget of Work-AGRI-CROPDokument27 SeitenBudget of Work-AGRI-CROPMaricel ManlupigNoch keine Bewertungen

- HEMPEL Decorative EngDokument99 SeitenHEMPEL Decorative EngILya Kryzhanovsky50% (2)

- Test Bank For MKTG 4th CanadianDokument30 SeitenTest Bank For MKTG 4th Canadianjosephrodriguezbjmsdzfoyi100% (25)

- 21 CFRDokument112 Seiten21 CFRVenkatesh Alla0% (1)

- AS9100 9145 - Guidance PDFDokument20 SeitenAS9100 9145 - Guidance PDF44abcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Astm A 924Dokument8 SeitenAstm A 924djfreditoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building A Global Brand: Bangalore Institute of Management StudiesDokument25 SeitenBuilding A Global Brand: Bangalore Institute of Management StudiesAnonymous d3CGBMzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cosmetic GMP ImplementationDokument23 SeitenCosmetic GMP ImplementationAndre Hopfner100% (2)

- Packaging LogisticsDokument31 SeitenPackaging LogisticsAkash Kumar KarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Packaging Labeling Technology in TheDokument13 SeitenManagement of Packaging Labeling Technology in TheFlexMashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shivaji University, Kolhapur.: IntroductionDokument62 SeitenShivaji University, Kolhapur.: IntroductionPrashant Inamdar100% (1)

- Formel QAuditDokument19 SeitenFormel QAuditthienthantuyetvh2000Noch keine Bewertungen

- Design Documentation L4Dokument27 SeitenDesign Documentation L4KOFI BROWNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Satisfaction Towards Pakaged Drinking WaterDokument21 SeitenConsumer Satisfaction Towards Pakaged Drinking WaterVictoria Lindsey100% (1)

- MSDS - Avesta Pickling Gel 122Dokument9 SeitenMSDS - Avesta Pickling Gel 122geoanburajaNoch keine Bewertungen