Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Why Was Augustus Concerned With The Family, Status and Manumission

Hochgeladen von

MrSilky2320 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

116 Ansichten4 SeitenAugustus was concerned with the family, status, and manumission of slaves due to the widely held Roman belief that moral decline had led to civil war. As princeps, Augustus sought to restore traditional Roman values through legislation regulating manumission, promoting marriage, and reducing adultery. However, his laws met with limited success, as many Romans continued extramarital relationships and found ways to avoid the requirements of marriage and childbearing. Overall, Augustus' social reforms did not substantially change Roman culture or demographics.

Originalbeschreibung:

aug

Originaltitel

Why Was Augustus Concerned With the Family, Status and Manumission

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenAugustus was concerned with the family, status, and manumission of slaves due to the widely held Roman belief that moral decline had led to civil war. As princeps, Augustus sought to restore traditional Roman values through legislation regulating manumission, promoting marriage, and reducing adultery. However, his laws met with limited success, as many Romans continued extramarital relationships and found ways to avoid the requirements of marriage and childbearing. Overall, Augustus' social reforms did not substantially change Roman culture or demographics.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

116 Ansichten4 SeitenWhy Was Augustus Concerned With The Family, Status and Manumission

Hochgeladen von

MrSilky232Augustus was concerned with the family, status, and manumission of slaves due to the widely held Roman belief that moral decline had led to civil war. As princeps, Augustus sought to restore traditional Roman values through legislation regulating manumission, promoting marriage, and reducing adultery. However, his laws met with limited success, as many Romans continued extramarital relationships and found ways to avoid the requirements of marriage and childbearing. Overall, Augustus' social reforms did not substantially change Roman culture or demographics.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 4

Samuel Taylor

Why was Augustus concerned with the family, status and

manumission? How successful was he?

The overriding mindset which seems to have permeated all Roman discussions or beliefs about

social issues is one that directly correlated moral rectitude of the people and the upper classes with

success and prosperity as a whole. As a consequence, it was thought that the major explicatory

factor for the turbulence which Rome had endured in the twenty or so years before the Battle of

Actium must have been some sort of moral decline. This perception is seen in Horaces works, which

directly attribute the civil wars to the debasement of the marriage-bed, of the Roman race as a

whole and of individual homes (Odes 3.6). This philosophy was the foundation of Augustus concern

with social issues such as the family, legal status and the manumission of slaves. We cannot be sure

how sincerely he himself shared this view and there were probably other factors involved anyway, to

a greater or lesser extent, such as political expediency and the desire to consolidate his dynasty, but

his role as a triumvir and later princeps was (nominally, at least) all to do with the state of society.

His mandate was to restore the Republic, and in doing so to remove all traces of wickedness (or

scelus) which had tainted the original values of the Republic and had caused so much damage.

Roman guilt about scelus gave Augustus the justification for his position and they saw this scelus as

rooted in domestic sins such as adultery. Augustus actions had the appearance, and maybe even

some substance, of moral restoration and his persistence over time suggests that his concern with

these issues stretched further than merely justifying his role in the new Rome. Although his legal

approach was fairly unsuccessful, we must be careful not to underestimate the significance of what

he was doing.

Before we discuss Augustus legislation about sexual conduct, one of the areas in which Romans

were thought to have fallen away from the principles of the Old Republic with negative

consequences was the area of Roman citizens granting freedom and Roman citizenship to slaves.

There were two major concern with this namely, that the emancipation of slaves was harming the

quality of the pool of Roman citizens, and that slaves were being manumitted for less-than-

wholesome reasons. Dionysius of Halicarnassus relates that some slaves were buying their freedom

with money that had been obtained criminally, that some were being freed as a reward for doing

something shady or illegal for their master, and that some masters were manumitting their slaves

solely for their own gain whether to obtain votes or favours, or to embellish their own

reputations

1

. In addition, it may have been the case that the extensive availability of slaves was

undermining other sources of manpower, such as the citizen-body. Augustus main response to the

issue of manumission and its effects lay in the Lex Iunia, which probably was issued in 17 BC, but

later on there was the 2 BC Lex Fufia Caninia and the 4 AD Lex Aelia Sentia. The Lex Fufia limited the

numbers of manumissions that were allowed in wills, while the latter restricted who could manumit

and which slaves could become citizens (primarily based on age requirements). When we look at his

legislation, we see that Augustus was definitely not trying to destroy the culture of manumission.

Rather, he was trying to regulate it and remove undesirable elements of it as part of a wider theme

of returning to the supposedly more morally sound and beneficial values of the Old Republic. As a

1

Braund p. 261

Samuel Taylor

result, it became the case that (in theory) only slaves whose good moral character made them

worthy of citizenship should be manumitted. The laws dont seem to have been part of a racial

policy of keeping Roman blood pure, as Suetonius suggests, so much as attempts to eliminate

immoral and illegal manumissions. Overall, it seems that actually Augustus policies about

manumission and the status of those freed were rather limited. This partly makes it difficult to

assess how successful he was. Both particular instances such as being able to refuse exceptions at

the requests of Tiberius and Livia (Suetonius 40) and the general sense in which his reforms were

not challenged very much suggest that he was successful in his limited aims.

We now come to Augustus policies about sexual conduct, which can be broadly divided into two

categories: measures seeking to reduce the levels of adultery and sexual promiscuity, and those

trying to promote marriage and childbirth. At the root of Roman guilt about scelus, mentioned

earlier, there was a particular concern about adultery, and it fell to Augustus to tackle this issue

because of his appointment by the people and the Senate as the supervisor and corrector of

morals. We know that Augustus himself was widely thought to be something of a philanderer

(Suetonius 67, Dio 54.16) and as such it seems odd for him to regulate this issue strictly and thus

somewhat hypocritically. However, the Senate wanted even stricter regulations than Augustus was

prepared to put in place (Dio 54.16) and it seems that there was a real drive behind anti-adultery

laws because it was thought to be particularly associated with instability and misfortune. As such,

moral regeneration was needed to regain stability and mythical greatness of the Old Republic. The

two main acts of Augustus on this topic, the Lex Iulia and the later Lex Papia Poppaea, were designed

to suppress adultery in quite restrictive ways. Under the Lex Iulia, adultery was openly associated

with treason and political subversion, and became a public offence for the first time. In this

supposed re-instatement of worthy, traditional, values, the link between sexual waywardness and

public disarray was emphasised by how adultery was treated as a destructive power. Making the

punishment for adultery more severe, as well as other things such as restricting who adulterers

could marry and promoting marriage itself, resulted in a Rome that was praised by Horace for being

undefiled by that sin (Odes 4.5). Despite this, it seems that Augustus anti-adultery measures were

relatively ineffective. His earlier attempts, in the 20s BC, failed rather miserably (Propertius 2.7),

while a lot of extra-marital sex remained legal even after the Lex Iulia

2

. Ultimately, Augustus could

not even stop his daughter and granddaughter from committing adultery, and had to punish them

accordingly. While in some ways, particularly in some of the poets, it might seem that Augustus

succeeded in cleansing Rome sexually, this was by no means the case. Propertius rejoicing in his

affair with Cynthia is just one example of how sexual promiscuity continued under Augustus just as it

had done before, despite the clamouring of the senate.

The close corollary of Augustus policy on adultery was the promotion of marriage. This was both a

practical concern and a moral one. On one level, some would argue, using Horaces Carmen

Saeculare among other things, that Rome was undergoing a birthrate problem

3

. The decimation of

the upper classes in the turbulent first century BC combined with a lack of offspring to replenish

their ranks meant that there was a need for marriage and childbirth to be encouraged. Yet because

of the negative associations with adultery, there was a sense in which marriage was more than a

2

Wallace-Hadrill 1993 p. 67

3

Williams p. 29

Samuel Taylor

pragmatic matter. In laws such as the Lex Papia Poppaea, Augustus provided benefits of rights and

privileges to couples who had children, while images emphasising the importance of families

witness the productively fertile women on the Ara Pacis tried to portray families as a joy rather

than a burden. Child-bearing was now not purely a private matter but required the intervention and

provision of the state. The most important fact about Roman marriage seems to have been that the

law about marriage was fulfilled by having children (Carmen Saeculare 19). This is reinforced by the

fact that opposition to the changes from the people and equestrian order seemed to be based on

the desire to avoid having offspring hence why some individuals married pre-pubescent girls and

changed wives frequently to try to get around the laws. Metellus Macedonius, the censor, used to

say that marriage was a boring duty to the state which had to be done

4

. We see Propertius valuing

his existing relationship with Cynthia above being a father. The laws encouraging marriage and

penalising singleness were actually probably relatively easy to evade, since they only really affected

the small group of people who were trying to obtain public office in Rome and the municipalities.

One effect of the legislation was the men seem to have started marrying younger, but overall the

laws tended to fail in their general aim. A law promoting marriage promoted childbirth, and the fact

that Augustus legislation probably had little demographic effect in the form of increasing numbers

of Roman citizens

5

, is probably indicative of an ineffectual measure. In the end, a culture of either

celibacy or childless sexual relationship was probably too embedded in Roman society for Augustus

top-down approach to work.

In conclusion, Augustus concern with issues surrounding the family, status and manumission

stemmed from a sense of the duty of his position to combat scelus and a practical sense of the need

to replenish a weakened upper class with a strong birth rate. In regulating the process of

manumission and putting laws into place about sex and marriage, Augustus was justifying his own

control and trying to secure the future of his rule with a feeling of returning to the values of the Old

Republic. The legislation itself was fairly unsuccessful, only having a moderate (at best) impact on

Roman society, but perhaps Augustus success in the social sphere lay in another area. His own

family was set up as the model for this new Roman family based on mythical Republican values.

Augustus himself (apart from his own adultery) lived reasonably simply and morally, which lent him

a degree of moral authority. He maintained a very tight rein on the activities of his family, for

example, strictly supervising the upbringing of the female members of his family, controlling their

marriages in forcing Agrippa and Tiberius to leave their wives and advancing Caius and Lucius to

state offices in such an unprecedented way. Despite his constant and intense presence in the lives of

his family, it is fair to say that they failed him. The adultery of his daughter and granddaughter

showed the futility of his anti-adultery measures, while the death of his grandsons was a huge

setback to his dynastic ambitions. His family failed to act as appropriate models of Augustan

morality, but that fact that his family played such a decisive role as the example in social matters

shows just how effectively Augustus had cemented the Julii as the imperial family.

4

Wallace-Hadrill 1985

5

Brunt p. 565

Samuel Taylor

Bibliography

Res Gestae Divi Augusti

Suetonius, Augustus

Cassius Dio, The Roman History

Horace, Carmen Saeculare and Odes

Propertius

Ovid, Fasti

David C. Braund, Augustus to Nero (Croon Helm 1985)

C. Pelling and J.A. Crook, Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 10 (Cambridge University Press 1996)

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, The Golden Age and Sin in Augustan Ideology, Past & Present, No. 95

(May, 1982)

Synnve des Bouvrie, Augustus legislation on morals which morals and what aims?, Symbolae

Osloenses: Norwegian Journal of Greek and Latin Studies, 59:1 (1984)

Gordon Williams, Poetry in the Moral Climate of Augustan Rome, The Journal of Roman Studies,

Vol. 52, Parts 1 and 2 (1962)

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Propaganda and Dissent? Augustan Moral Legislation and the Love-Poets,

Klio, 67:1 (1985)

Karl Galinsky, Augustus' Legislation on Morals and Marriage, Philologus, 125:1 (1981)

Jasper Griffin, Augustan Poetry and the Life of Luxury, The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 66 (1976)

Catharine Edwards, The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome (Cambridge University Press 1993)

P.A. Brunt, Italian Manpower (Oxford University Press 1971)

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Augustan Rome (Bristol Classical Press 1993)

Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (The Folio Society 2009)

Keith Hopkins, Conquerors and Slaves (Cambridge University Press 1978)

K.R. Bradley, Slaves and Masters in the Roman Empire (Latomus 1984)

Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (University of Michigan Press 1988)

J.A. Crook, Law and Life of Rome (Thames and Hudson 1967)

Charles Brian Rose, Dynastic Commemoration and Imperial Portraiture in the Julio-Claudian Period

(Cambridge University Press 1997)

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Ancient Law: Its Connection to the History of Early SocietyVon EverandAncient Law: Its Connection to the History of Early SocietyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roman Citizenship: Marriage and FamilyDokument39 SeitenRoman Citizenship: Marriage and FamilyEve AthanasekouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti Arjava Women&LawDokument4 SeitenAnti Arjava Women&LawΚριστοφορ ΚολομβοςNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maines Idea of Law @2Dokument9 SeitenMaines Idea of Law @2Avni NayakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Incest Laws and Absent Taboos in Roman Egypt Anise K. StrongDokument10 SeitenIncest Laws and Absent Taboos in Roman Egypt Anise K. StrongAnise K. Strong-MorseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Society: For More Details On This Topic, SeeDokument9 SeitenSociety: For More Details On This Topic, Seeshinrin16Noch keine Bewertungen

- Justiniano - Institutiones (Latín - Inglés)Dokument564 SeitenJustiniano - Institutiones (Latín - Inglés)Bertran2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Formula Procedure of Roman Law - KocourekDokument20 SeitenFormula Procedure of Roman Law - KocourekErenNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Culture: A Story: Bruce P. FrohnenDokument9 SeitenAmerican Culture: A Story: Bruce P. Frohnenpriya_psalmsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Incest Laws and Absent Taboos in Roman EgyptDokument11 SeitenIncest Laws and Absent Taboos in Roman EgyptDaniel Knight100% (1)

- D. Heith-Stade, Marriage in The Canons of The Council in TrulloDokument19 SeitenD. Heith-Stade, Marriage in The Canons of The Council in TrullopiahermanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Fusion of Law and EquityDokument11 SeitenThe Fusion of Law and EquityElaine TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Law: Sir Henry MaineDokument129 SeitenAncient Law: Sir Henry MaineGutenberg.org100% (1)

- A Little CommonwealthDokument6 SeitenA Little CommonwealthMichael WaldrenNoch keine Bewertungen

- FinalpaperDokument9 SeitenFinalpaperapi-315917059Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient LawDokument168 SeitenAncient LawAnonymous nYwWYS3ntV100% (1)

- Family Law in Roman Law. 2Dokument8 SeitenFamily Law in Roman Law. 2Nothando NgwenyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Watson-1972-Roman Private Law and TheDokument6 SeitenWatson-1972-Roman Private Law and TheFlosquisMongisNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Home University Library of Modern Knowledge XXI LiberalismDokument77 SeitenThe Home University Library of Modern Knowledge XXI Liberalism0bs01337Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ohbrl GenderDokument40 SeitenOhbrl GenderArthur CurveloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Same Sex Marriage, History and PerspectiveDokument90 SeitenSame Sex Marriage, History and Perspectiveamin jamalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Paterfamilias in Roman LawDokument9 SeitenThe Role of Paterfamilias in Roman LawIonelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discuss The Nature and Extent of Slavery As An Institution in Greco-Roman SocietyDokument4 SeitenDiscuss The Nature and Extent of Slavery As An Institution in Greco-Roman SocietySouravNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Philosophy of The Civil CodeDokument23 SeitenThe Philosophy of The Civil CodeTeodoro Jose BrunoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Law Its Connection to the History of Early SocietyVon EverandAncient Law Its Connection to the History of Early SocietyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Society: Further InformationDokument12 SeitenSociety: Further InformationCulea ElissaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roman Concepts of EqualityDokument29 SeitenRoman Concepts of Equalitytatarka01Noch keine Bewertungen

- . . . Down Will Come Roe, Babies and All: A Road Map for Overruling Roe Vs. WadeVon Everand. . . Down Will Come Roe, Babies and All: A Road Map for Overruling Roe Vs. WadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Augustus and The OrdinesDokument4 SeitenAugustus and The OrdinesMrSilky232Noch keine Bewertungen

- Beggar Thy Neighbor: A History of Usury and DebtVon EverandBeggar Thy Neighbor: A History of Usury and DebtBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- Roman Concept of JusticeDokument15 SeitenRoman Concept of JusticeNavjot SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- H. S. Maine - 2007 - Ancient Law - Its Connection To The History of Early SocietyDokument162 SeitenH. S. Maine - 2007 - Ancient Law - Its Connection To The History of Early SocietyNATALIA ALICIA PENRROZ SANDOVALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Order and Dispute: An Introduction to Legal AnthropologyVon EverandOrder and Dispute: An Introduction to Legal AnthropologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wiley American Bar FoundationDokument7 SeitenWiley American Bar Foundationshubh1612Noch keine Bewertungen

- Oliver Wendell Holmes JRDokument220 SeitenOliver Wendell Holmes JRAnzhela KosarevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DefamationDokument29 SeitenDefamationVenushNoch keine Bewertungen

- ROMAN DUTCH LAW by MHOFUDokument21 SeitenROMAN DUTCH LAW by MHOFUtatendaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Directions in Sexual Harassment LawDokument39 SeitenDirections in Sexual Harassment LawKatrina Janine Cabanos-ArceloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oxford University Press, The Past and Present Society Past & PresentDokument23 SeitenOxford University Press, The Past and Present Society Past & PresentmiraclebusttrailNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ancient City: A Study of the Religion, Laws, and Institutions of Greece and RomeVon EverandThe Ancient City: A Study of the Religion, Laws, and Institutions of Greece and RomeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (35)

- British Institute of International and Comparative LawDokument5 SeitenBritish Institute of International and Comparative LawSergeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Position of Women in The Late Roman Republic - Helen Wieand - Part 1 ArticleDokument15 SeitenThe Position of Women in The Late Roman Republic - Helen Wieand - Part 1 ArticleKassandra M JournalistNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hist 4150 Midterm Paper 3Dokument10 SeitenHist 4150 Midterm Paper 3api-710608388Noch keine Bewertungen

- 霍姆斯:普通法(THE COMMON LAW)Dokument171 Seiten霍姆斯:普通法(THE COMMON LAW)Benedito ZepNoch keine Bewertungen

- 霍姆斯:普通法(THE COMMON LAW)Dokument171 Seiten霍姆斯:普通法(THE COMMON LAW)Benedito ZepNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Common LawDokument254 SeitenThe Common LawJason HenryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Roman Munificence - The Development of The Practice and LaDokument69 SeitenAncient Roman Munificence - The Development of The Practice and LaRafael Horta ScaldaferriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Donald W. Bradeen - Roman Citizenship Per MagistratumDokument9 SeitenDonald W. Bradeen - Roman Citizenship Per MagistratumAnyád ApádNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forums Amphitheatres Racetracks Baths: Legal StatusDokument2 SeitenForums Amphitheatres Racetracks Baths: Legal StatusAnnabelle ArtiagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History of Ancient Rome: Book II: From the Abolition of the Monarchy in Rome to the Union of ItalyVon EverandThe History of Ancient Rome: Book II: From the Abolition of the Monarchy in Rome to the Union of ItalyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gale Researcher Guide for: The Origins of the US Criminal Justice SystemVon EverandGale Researcher Guide for: The Origins of the US Criminal Justice SystemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law of PersonsDokument24 SeitenLaw of PersonsLitharaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Superstition and Force: Essays on the Wager of Law, the Wager of Battle, the Ordeal, TortureVon EverandSuperstition and Force: Essays on the Wager of Law, the Wager of Battle, the Ordeal, TortureNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foucault Truth and Juridical FormsDokument11 SeitenFoucault Truth and Juridical FormsFalalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Augustus and The OrdinesDokument4 SeitenAugustus and The OrdinesMrSilky232Noch keine Bewertungen

- How Did The Augustan Building Programme Help To Consolidate Imperial PowerDokument4 SeitenHow Did The Augustan Building Programme Help To Consolidate Imperial PowerMrSilky232100% (1)

- Was This A Period of Government GrowthDokument4 SeitenWas This A Period of Government GrowthMrSilky232Noch keine Bewertungen

- Revolutions Natural Phenomenon or Learned BehaviorDokument4 SeitenRevolutions Natural Phenomenon or Learned BehaviorMrSilky232Noch keine Bewertungen

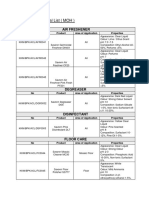

- Trinity WeightsDokument2 SeitenTrinity WeightsMrSilky232Noch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Weight Training ProgrammeDokument4 SeitenPersonal Weight Training ProgrammeMrSilky232Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fitness TestingDokument24 SeitenFitness TestingMrSilky232Noch keine Bewertungen

- Does Suleiman I Deserve The Title 'MagnificentDokument8 SeitenDoes Suleiman I Deserve The Title 'MagnificentMrSilky232100% (1)

- 2009 Annual Report - NSCBDokument54 Seiten2009 Annual Report - NSCBgracegganaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approved Chemical ListDokument2 SeitenApproved Chemical ListSyed Mansur Alyahya100% (1)

- Chapter 12 Social Structural Theories of CrimeDokument5 SeitenChapter 12 Social Structural Theories of CrimeKaroline Thomas100% (1)

- Department of Chemistry Ramakrishna Mission V. C. College, RaharaDokument16 SeitenDepartment of Chemistry Ramakrishna Mission V. C. College, RaharaSubhro ChatterjeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hilti Product Technical GuideDokument16 SeitenHilti Product Technical Guidegabox707Noch keine Bewertungen

- Problem ManagementDokument33 SeitenProblem Managementdhirajsatyam98982285Noch keine Bewertungen

- Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageDokument11 SeitenChildbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageWenny Indah Purnama Eka SariNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACE Resilience Questionnaires Derek Farrell 2Dokument6 SeitenACE Resilience Questionnaires Derek Farrell 2CATALINA UNDURRAGA UNDURRAGANoch keine Bewertungen

- Calendar of Cases (May 3, 2018)Dokument4 SeitenCalendar of Cases (May 3, 2018)Roy BacaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Finance and The SMEsDokument6 SeitenBusiness Finance and The SMEstcandelarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q&A JurisdictionDokument20 SeitenQ&A JurisdictionlucasNoch keine Bewertungen

- MCN Drill AnswersDokument12 SeitenMCN Drill AnswersHerne Balberde100% (1)

- A Guide To Effective Project ManagementDokument102 SeitenA Guide To Effective Project ManagementThanveerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digital TransmissionDIGITAL TRANSMISSIONDokument2 SeitenDigital TransmissionDIGITAL TRANSMISSIONEla DerarajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing - Hidden Curriculum v2 EditedDokument6 SeitenWriting - Hidden Curriculum v2 EditedwhighfilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atul Bisht Research Project ReportDokument71 SeitenAtul Bisht Research Project ReportAtul BishtNoch keine Bewertungen

- UT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Dokument1 SeiteUT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Atharv KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study 1 (Pneumonia)Dokument13 SeitenCase Study 1 (Pneumonia)Kate EscotonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 INTRODUCTION TO PRESTRESSED CONCRETEDokument15 SeitenChapter 4 INTRODUCTION TO PRESTRESSED CONCRETEyosef gemessaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy of Jnanadeva - As Gleaned From The Amrtanubhava (B.P. Bahirat - 296 PgsDokument296 SeitenPhilosophy of Jnanadeva - As Gleaned From The Amrtanubhava (B.P. Bahirat - 296 PgsJoão Rocha de LimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joshua 24 15Dokument1 SeiteJoshua 24 15api-313783690Noch keine Bewertungen

- CEI and C4C Integration in 1602: Software Design DescriptionDokument44 SeitenCEI and C4C Integration in 1602: Software Design Descriptionpkumar2288Noch keine Bewertungen

- 04 RecursionDokument21 Seiten04 RecursionRazan AbabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Windows SCADA Disturbance Capture: User's GuideDokument23 SeitenWindows SCADA Disturbance Capture: User's GuideANDREA LILIANA BAUTISTA ACEVEDONoch keine Bewertungen

- Dispersion Compensation FibreDokument16 SeitenDispersion Compensation FibreGyana Ranjan MatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- STAFFINGDokument6 SeitenSTAFFINGSaloni AgrawalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1E Star Trek Customizable Card Game - 6 First Contact Rule SupplementDokument11 Seiten1E Star Trek Customizable Card Game - 6 First Contact Rule Supplementmrtibbles100% (1)

- Welcome LetterDokument2 SeitenWelcome Letterapi-348364586Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gandhi Was A British Agent and Brought From SA by British To Sabotage IndiaDokument6 SeitenGandhi Was A British Agent and Brought From SA by British To Sabotage Indiakushalmehra100% (2)

- Hedonic Calculus Essay - Year 9 EthicsDokument3 SeitenHedonic Calculus Essay - Year 9 EthicsEllie CarterNoch keine Bewertungen