Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Seeds of Sustainable Consumption Patterns: Society For Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003

Hochgeladen von

AamerMAhmadOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Seeds of Sustainable Consumption Patterns: Society For Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003

Hochgeladen von

AamerMAhmadCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Proceedings, 1

st

International Workshop on Sustainable Consumption in Japan,

Society for Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003.

3

The seeds of sustainable consumption patterns

Edgar Hertwich

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)

A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria

Phone +43-2236-807-449, Fax +43-2236-71313

hertwich@iiasa.ac.at

Abstract

We present five examples of sustainable consumption measures or

campaigns: organic food, changing washing machine use, renting efficient white-

goods, a sustainable lifestyles campaign, and a car-free housing development. The

environmental and social impacts of consumption are largely determined through

infrastructure, the goods and services available, and habits. Our examples affect

habitual use behaviour, the availability of and access to sustainable solutions, or the

overall organisation of life. We judge that any of these three targets is important.

Sustainable consumption research should focus more on how to shape habits and

how to improve the availability and acceptance of sustainable solutions.

Introduction

The need to "chang[e] unsustainable patterns of consumption and

production" has been firmly acknowledged by the World Summit for Sustainable

Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg. The WSSD Plan for Implementation

contains a description of a "10-year framework of programmes in support of regional

and national initiatives to accelerate the shift towards sustainable consumption and

production []," which world leaders resolve to implement (United Nations General

Assembly 2002, 13).

As a contribution to the development and planning of this work programme,

I review selected actions, initiatives, and measures that contribute to reducing the

environmental pressures and social repercussions of consumption. These examples,

mostly from Europe, have been identified in a research project on examples of

sustainable consumption (Hertwich and Katzmayr 2003). I evaluate the contribution

of the examples given a background on the debate about sustainable consumption. I

investigate to what degree these examples can serve as seeds for more sustainable

consumption patterns, addressing the concerns with the present patterns raised by

the Rio and Johannesburg Earth Summits.

Patterns of consumption and production are not sustainable in developed or

developing countries. In developed countries, the levels of pollution, especially those

causing global change, are far too high and trends go in the wrong direction. In

developing countries, there is too much strain on the local resource base, and this

strain is increasing due to population growth, increases in wealth and urbanisation.

The need to address consumption follows from the global environment &

development agenda, which emerged from the Rio Earth Summit. This agenda

includes the right to develop for the global poor and aims for a convergence of

affluence. The common perception, although hardly ever explicitly articulated, is that

this convergence will be at the level of the middle class. What Nathan Keyfitz (1998)

calls the "middle class package" includes various appliances, communication

equipment, and - most clearly visible - a car. Being concerned about the

environmental effects of such a policy, Keyfitz, the former head of the IIASA

population project, reviews four types of measures to reduce environmental impacts:

1. 'end-of-pipe' measures, such as catalysts, sewage treatment plants and filters

Proceedings, 1

st

International Workshop on Sustainable Consumption in Japan,

Society for Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003.

4

2. 'increases in mechanical efficiency,' such as increased car mileage, increase

insulation of houses etc.

3. 'raising use efficiency': multiple-flat houses, public instead of private

transportation, car sharing etc

4. 'lifestyle change'

After reviewing the first three types of measure, Keyfitz (1998, p. 496)

arrives at following conclusion: "But even with these [ecoefficiency and use] changes,

a population of 10 billion could not be accommodated in the style of life described as

middle class without irreparable damage to the environment. That style would have

to be more radically changed than indicated above."

To bring about sustainable patterns of consumption and production, or a

situation in which the production, distribution, use and disposal of goods consumed

no longer causes undue strain on the environment or undesirable social effects,

fundamental changes are required. But what needs to change, and how? There is the

option to accelerate increases in eco-efficiency through improvements in production

methods and the design of products. There is the option to reduce or halt the growth

of consumption until autonomous eco-efficiency improvements catch up with past

consumption growth. Is it possible to shift the focus of consumption to things less

material, less pollution intensive? Is it possible and desirable to pursue a sufficiency

approach, decoupling social well-being from a growth in consumption? I do not

attempt to address all these questions here, but I raise them to indicate that, opening

the Pandora's box of sustainable consumption, we arrive at a research agenda that

addresses fundamental questions regarding the future course of our civilization.

The environmental impacts of consumption

Because there is a paucity of data on the social impacts of consumption, this

review focuses on the few environmental indicators for which data exists.

Traditionally, national levels of emissions and resource use are tracked and

compared on a per-capita basis. This lumps together emissions caused by domestic

production and those caused by consumption itself. This is misleading, because in an

open economy, much of domestic production is not for the purpose of domestic

consumption and many of the products and services consumed are imported. In a

time series analysis, effects of increasing specialisation obscure the effects of changes

in consumption. In a cross-sectional analysis, countries with resource-intensive

exports look worse. In addition, emissions and energy use connected to international

transport, i.e. shipping and air transport, are not accounted anywhere. To determine

the environmental impact of consumption, including that connected to the

production, delivery and disposal of the goods consumed, one uses input-output

models and life-cycle assessment. Unfortunately, such analyses are not available for

many countries and especially not as a time series. Most models for the

environmental impacts from consumption are based only on domestic numbers. At a

recent workshop on life-cycle approaches to sustainable consumption at IIASA,

several attempts to account for the different environmental impacts that occur in

different countries of origin were presented (Goedkoop et al. 2002; Hertwich et al.

2002; Munksgaard et al. 2002). Hertwich et al. (2002) have shown that in Norway

more than 70% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are associated with production

for export. Counted at domestic pollution intensities, import is responsible for about

25% of the indirect household GHG emissions. The emission intensities of Norwegian

industry, however, are significantly different from the emission intensities of the

same sectors of key trading partners, such as China and Japan. The expected

influence of these differences on the overall household emissions is appreciable but

not dramatic. The potential errors are so large, however, that the domestic numbers

Proceedings, 1

st

International Workshop on Sustainable Consumption in Japan,

Society for Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003.

5

should not be used when comparing different households in Norway or

recommending changes in consumption patterns.

In spite of these limitations of currently available figures, interesting

patterns emerge. Aggregate national figures show that resource consumption and

linked pollutants increase with time, although at a rate smaller than the parallel

increase in economic activity as measured by the gross domestic product. Only

pollutants that can easily be addressed by end-of-pipe measures show a downward

trend after a peak. While much has been made of this trend and the linked

hypothesis of a reduction of pollution with wealth ("Environmental Kuznets Curve"),

wealth has not been proven as a causal factor and autonomous technological change

with time emerges as a strong contender (De Bruyn 2000). What is interesting,

however, is that there are significant national differences in emissions per capita

that cannot be explained by levels of wealth. Grbler (1998) points to the existence of

development trajectories, as they are displayed in Figure 1. I believe that the path-

dependence of environmental impacts is something that can be seen not only on the

national level, where it has been documented, but also for regions, towns, and even

single individuals. This has not yet been investigated, but I will return to this theme

later.

Figure 1: Primary energy use (toe/capita) versus GDP/capita for major world regions

(1990 USD at market exchange rates and purchasing power parity) and two historical

trajectories for the US and Japan. Source (Grbler 1998)

Investigations of energy use and CO2 emissions per household show that,

within European countries and the US, there is a strong correlation between

household expenditure and direct as well as indirect emissions. While indirect

emissions are proportional to expenditure, direct emissions sometimes show a less

steep increase in some countries, so that the emissions per unit expenditure may be

slightly lower for rich households than for poor households. Vringer and Blok (1995;

2000) showed that, in the Netherlands, additional explanatory variables are

household size, car ownership, and urban/rural differences. They are responsible for

about 40% of the variance among households at the same expenditure level displayed

in Figure 2.

Proceedings, 1

st

International Workshop on Sustainable Consumption in Japan,

Society for Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003.

6

To summarise, the environmental and social impacts of consumption are

known at best on the aggregate level. A number of important impacts remain to be

quantified, and the connection between specific consumption patterns and the

resulting impacts remains to be determined. The currently available data shows a

strong connection between levels of wealth and energy use, but also interesting

differences both among nations and among different households within a nation.

These differences remain to be explained, but they point at the potential for less

impacting consumption patterns at comparable levels of wealth.

Figure 2: Total energy requirement per household versus household expenditure for the

Netherlands. Source: (Vringer and Blok 1995).

Addressing Sustainable Consumption

UNEP has recently

suggested using the life 'functions'

nutrition, mobility, housing,

clothing, health and education as a

way to organize its work on

sustainable consumption and

production (UNEP 2002). Functions

can be seen as components of

lifestyles. Functions are fulfilled by

different products and services. This

is a useful manner of organizing the

analysis of sustainable consumption

issues. It is important, however, to

also address the entire consumption

pattern of a population, the lifestyle.

Otherwise sustainable consumption

would stop at what Keyfitz calls use

efficiency. A total reduction of

impacts could not be guaranteed,

because the time and income rebound effects could lead to increases in emissions

Lifestyle

Housing

Clothing

Mobility

Health Leisure

Nutrition

Lifestyle

Housing

Clothing

Mobility

Health Leisure

Nutrition

Figure 3: Functions as components of lifestyle.

Proceedings, 1

st

International Workshop on Sustainable Consumption in Japan,

Society for Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003.

7

related to other functions. We have used functions to organise the analysis of

sustainable consumption measures, but we have also used lifestyle as a separate,

overarching category (Figure 3). Hertwich and Katzmayr (2003) have described 34

campaigns, policy measures, individual or corporate actions that could be described

as examples of sustainable consumption. These were selected from a larger group of

examples identified in the electronic appendix of the report. These measures address

the functions of mobility (8), housing (6), clothing (8) and nutrition (4), as well as the

cross-cutting areas of appliances (4) and lifestyles (4). In this paper, I describe only

five examples and discuss their general features.

Examples of sustainable consumption

The "WashRight" campaign

The International Association for Soaps, Detergents and Maintenance

Products (AISE) conducts a campaign that attempts, among other things, to reduce

the washing temperature (to 30 and 40

o

C) and encourage a fully loaded laundry

machine (www.washright.com). The campaign also attempts to reduce the detergent

consumption and the packaging material. The campaign uses TV advertisements and

leaflets. WashRight is a voluntary industry initiative based on a code of conduct. In

some way, it only strengthens an ongoing trend. Average wash temperatures in

Europe have dropped from 65 to 48

o

C over the last decade (Uitdenbogerd 2001). This

trend has been enabled by better detergents and by easy-care fabrics such as new

synthetics. The lower temperature leads to substantial energy savings. For a 1996

reference washing machine, electricity use was 2.32 kWh/cycle for 90

o

C, 1.45 for 60

o

C, 0.76 for 40

o

C and 0.44 for 30

o

C. A continuation of the trend towards lower

temperatures, together with an increase in laundry machine efficiency, can bring a

substantial reduction of electricity used for washing.

FUNSERVE Functional Service Contracts for White Goods

This project started in 1999 and has the aim to develop and field-test in the

EU member states Austria, Germany, Sweden and the UK the approach to offer

customers the services that they need instead of the products that provide these

services. Three electric utilities in Germany and Austria and the appliances

manufacturer Electrolux cooperate in leasing highly efficient appliances to the

customer. The leasing scheme includes free delivery and installation with

instructions on the optimal use, free repairs and a service hotline, and the removal of

the appliance after the agreed period. The targets of this project are, among others,

to assess the benefits and the costs for the participants and the environmental and

market potential, and to test the market acceptance. The customer surveys have

provided promising perspectives; also the retail trade has shown a high interest in

participating. Concerning the environmental effects, a 10% market share of the

appliances would reduce the energy consumption by at about 7TWh, which

corresponds to a saving of CO2 emissions of at about 3 million tons per year.

Moreover, 50 million m

3

water and 26.000 tons of detergents could be saved each

year (Dudda et al. 2001).

Organic food lines of supermarket chains

Organic labels transmit information about the conditions of production to

the consumer and thus allow the consumer to make decisions that are in accordance

with the consumers' values and preferences. Organic products are usually also more

expensive. An example for sustainable consumption with respect to organic food is

the British supermarket chain Iceland. It converted its entire frozen vegetable line to

Proceedings, 1

st

International Workshop on Sustainable Consumption in Japan,

Society for Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003.

8

organics, at no extra cost to consumers. Its initiative, which removed at a stroke the

principal consumer objection to organic food, that it costs a lot more, put the rest of

Britain's supermarket chains, many of which sell organics at very high mark-ups, on

the defensive and under pressure to follow suit. Nonetheless, 6 months later the

company abandoned the six-month-old plan to sell only organic "own-brand" frozen

products, after an unexpected slump of 1.5 per cent in sales. Another attempt, the

"Ja Natuerlich" line of Billa in Austria, focused on produce, bulk and dairy products.

It was highly successful in giving the Billa high-quality image and attracting wealthy

customers. The number of products and the market share has steadily increased.

Action at Home

"Action at Home" is a so-called social marketing campaign operated by the

Global Action Plan in the United Kingdom.

1

Participants receive a questionnaire to

establish a baseline of household environmental impact called Greenscore, which is

measured again at the end of the programme. A monthly information pack provides

step-by-step suggestions for making small changes to their practices. Packs cover

waste, water, transport, shopping and energy, as well as 'next steps.' Over 30000

households have taken part in Action at Home. Unfortunately, the return of

questionnaires has been low, so that the Global Action Plan cannot judge the impact

of the campaign (Hobson 2002). For the "Sustainable Lifestyle Campaign" in the

United States, the Global Action Plan claims savings of 9-17% of the household

energy use, 16-20% of transportation fuel, and even larger amounts of water and

garbage. This results in savings of USD 200-400 per year in utility costs. It is not

clear, however, how representative and reproducible these number are. Hobson

(2002) reports that only half of the UK participants that she interviewed have

changed their behaviour, and that most changes were minor and could be done with

no cost and little effort, such as turning off the tap when brushing teeth. She

criticizes the focus of Action at Home on "rationalizing lifestyles" and instead

suggests a focus on social action and fairness.

Car-free housing project Vienna-Floridsdorf

This apartment complex includes 244 flats of different sizes (50-130 m

2

) and

was opened in the year 1999 as a demonstration project for car-free housing on the

periphery of Vienna(GEWOG 2000). The apartment complex includes garages only

for bikes and for car-sharing. The money saved from not providing one parking space

per flat was invested in common areas, such as social rooms and a playground. The

project includes an office for teleworkers and free-lancers, a fitness room, and a

distribution/storage room for organic food. Solar energy is used for hot water heating.

The apartment building is located near the old and the new Danube has therefore

easy access to recreational areas. Access to the city is available through a nearby

subway station. Only 5% of the trips of residents are with cars, 58% are with public

transport and the remainder is walking and biking.

Classification and Analysis of Examples

We have classified the examples of sustainable consumption according to

function, type of change (going back to Keyfitz' categorization) and mechanism of

action. Most of the examples identified fall into the mechanical or use efficiency

category. We even put organic food there, because it works through changed

production methods which reduce pollution; it is like purchasing any other clean

1

http://www.globalactionplan.org.uk/aboutus/athome.htm. The Global Action Plan and its "Sustainable

Lifestyle Campaign" started in the United States (http://www.globalactionplan.org). Similar activities

also exist in Canada (http://www.toolsofchange.com).

Proceedings, 1

st

International Workshop on Sustainable Consumption in Japan,

Society for Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003.

9

product. In terms of mechanisms of action, the WashRight campaign works through

convincing people to change their habits and lower the wash temperatures. Funserve

increases the access to high-efficiency white goods by removing the initial cost

barrier and spreading the costs out over the use phase, where they are compensated

by lower electricity costs. Organic food lines work like eco-labels, providing

information about the production of a product, and it makes organic food available or

more easily accessible to customers. The "Action at home" lifestyle campaign aims

mainly at changing habits and routines which increase the use efficiency of various

household functions. In some way, it may also be seen as affecting the lifestyle by

introducing environmental considerations into day-to-day decision making. The car-

free building in Vienna puts inhabitants into a more sustainable set-up. The building

is a micro-infrastructure offering access to playgrounds, socializing opportunities,

ready access to car sharing. There are also shared values among the inhabitants, so

that inhabitants encourage each other by example and through social pressure to

reduce car use, separate the garbage, and buy organic food.

Example Function Type of change Mechanism of action

WashRight Campaign Clothing Use changing habits and

routines

FUNSERVE white

good rental

Nutrition,

clothing

Mechanical Improved availability

through changed incentives

Organic food line at

supermarket

Nutrition Mechanical

lifestyle?

availability & information

on sustainable product

Action at Home various,

lifestyle

Use & mechanical

changing habits and

routines

Car-free housing

Vienna

Mobility,

housing,

lifestyle

Use

lifestyle?

more sustainable set-up

The discussion about sustainable consumption focuses naturally on the

choices household make and possibilities to reduce environmental and social impacts

through improving day-to-day decision making. Through changing daily, consciously

made choices, however, we are able to affect only small fraction of the direct and

indirect impacts caused by households. The level of impact is largely predetermined

either through factors the consumer has very little influence over, such as the

available infrastructure, the nature of the energy system and the properties of

products and services available, or through habits, social expectations, and long-term

decisions e.g. about where to live. In our opinion, we should focus more on these

factors, which shape the long-term development of our society:

Infrastructure: Change the infrastructure so sustainable lifestyles become more

attractive, transport is reduced, and public transport, biking and walking are

made easier and more popular.

Habit formation: Investigate and influence the formation of habits and routines.

A better understanding of the processes of culturalization and socialization (Wilk

2002) is required. As Faye Duchin pointed out at the workshop at IIASA, we need

to understand the human life-cycle and attempt to influence decision making at

stages of change, e.g. when one person establishes her first own household.

Availability and access to products and services that reduce the impact of

household consumption. Sustainable solutions, even if they do not achieve

universal market penetration, are important because they indicate a

development alternative, influence the development of conventional products,

and may be adopted in situations of crisis. For appliances, market transformation

programs have increased the efficiency of the entire product spectrum.

Proceedings, 1

st

International Workshop on Sustainable Consumption in Japan,

Society for Non-Traditional Technology, Tokyo 19-20 May 2003.

10

Conclusions

The examples of sustainable consumption reviewed range from targeting

specific, small changes in behaviour, such as reducing the clothes washing

temperature (100s MJ/person/year) to fundamental changes of how individuals

organise their life through car-sharing and more local activities (10,000s of

MJ/person/year). They may target many million individuals (WashRight) or only a

small, self-selected group (car-free housing). Further research on these examples is

recommended, combining life-cycle assessment type studies with social research.

This research should investigate the effectiveness and acceptance of different

measures by different groups/in different cultures. It should help develop measures

that target individuals when they are susceptive to changes, either when they make

big decisions (where to live, whether to buy a car) or when they form habits and

routines. Research should not only focus on individuals and their socialization, but

also on regions, regional planning, and infrastructure development.

Literature

De Bruyn, S. M. 2000. Economic growth and the environment-- an empirical analysis. Tinbergen

institute research series. Dordtrecht: Kluwer.

Dudda, C., S. Thomas, and K. Schuster. 2001. Functional service contracts for white goods: Selling a

function instead of a product (funserve). Paper read at 2001 eceee Summer study proceedings,

11-16 June, Mandelieu, France.

GEWOG. 2000. Model project car-free housing - project information (german). Vienna: GEWOG

Gemeinntzige Wohnungsbau GmbH.

Goedkoop, M. J., J. Madsen, D. S. Nijdam, and H. C. Wilting. 2002. Environmental load from private

dutch consumption. In Life-cycle Approaches to Sustainable Consumption -- Workshop

Proceedings, 22 November 2002, IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria.

Grbler, A. 1998. Technology and global change. Cambridge.: Cambridge University Press.

Hertwich, E. G., K. Erlandsen, K. Srensen, J. Aasness, and K. Hubacek. 2002. Pollution embodied in

Norway's import and export and its relevance for the environmental profile of households. In

Life-cycle Approaches to Sustainable Consumption -- Workshop Proceedings, 22 November

2002, Laxenburg, Austria.

Hertwich, E. G., and M. Katzmayr. 2003. Examples of sustainable consumption. Laxenburg, Austria:

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Hobson, K. 2002. Competing discourses of sustainable consumption: Does the 'rationalisation of

lifestyles' make sense? Environ. Politics 11 (2):95-120.

Keyfitz, N. 1998. Consumption and population. In The ethics of consumption: Good life, justice, and

global stewardshipedited by D. A. Crocker and T. Linden. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Munksgaard, J., M. Wier, M. Lenzen, and C. Day. 2002. Indicators for the environmental pressure of

consumption. Paper read at Life-cycle Approaches to Sustainable Consumption -- Workshop

Proceedings, 22 November 2002, IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria.

Uitdenbogerd, D. 2001. Appliance labelling from a consumer's perspective: Priorities in cloth washing.

Paper read at Further than ever from Kyoto? Rethinking energy efficiency can get us there.

2001 Summer study proceedings, 11-16 June, Mandelieu, France.

UNEP. 2002. UNEP contribution to framework on promoting sustainable consumption and production

patterns. Paris: United Nations Environment Program, Division for Technology, Industry and

Economics.

United Nations General Assembly. 2002. World summit on sustainable development: Plan of

implementation. Johannesburg: United Nations Division for Sustainable Development.

Vringer, K., and K. Blok. 1995. The direct and indirect energy requirements of households in the

Netherlands. Energy Pol 23 (10):893-910.

. 2000. Long-term trends in direct and indirect household energy intensities: A factor in

dematerialization? Energy Pol 28:713-727.

Wilk, R. 2002. Consumption, human needs, and global environmental change. Global Environm.

Change 12 (1):5-13.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Gasification of Waste Materials: Technologies for Generating Energy, Gas, and Chemicals from Municipal Solid Waste, Biomass, Nonrecycled Plastics, Sludges, and Wet Solid WastesVon EverandGasification of Waste Materials: Technologies for Generating Energy, Gas, and Chemicals from Municipal Solid Waste, Biomass, Nonrecycled Plastics, Sludges, and Wet Solid WastesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Example of Risk Assessment For A WarehouseDokument6 SeitenExample of Risk Assessment For A WarehouseSean Clark100% (1)

- Electricity Bill Receipt PDFDokument1 SeiteElectricity Bill Receipt PDFPranay Nayan0% (1)

- R1 BTG Interlocks& ProtectionsDokument62 SeitenR1 BTG Interlocks& ProtectionsDevanshu Singh100% (4)

- Carbon Footprints and Consumer Lifestyles: An Analysis of Lifestyle Factors and Gap Analysis by Consumer Segment in JapanDokument25 SeitenCarbon Footprints and Consumer Lifestyles: An Analysis of Lifestyle Factors and Gap Analysis by Consumer Segment in JapanJuuzou Tooru Karma TobioNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Consumerism" and Environment: Does Consumption Behaviour Affect Environmental Quality?Dokument17 Seiten"Consumerism" and Environment: Does Consumption Behaviour Affect Environmental Quality?Sana IrfanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Environmental Accounting and Reporting On Sustainable Development in NigeriaDokument10 SeitenThe Impact of Environmental Accounting and Reporting On Sustainable Development in NigeriaSunny_BeredugoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SkripsiDokument28 SeitenSkripsiAnita hutasoitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Benefits and Disadvantages of Economic Specialisation Within Global Markets, and Implications For SCP MonitoringDokument20 SeitenEnvironmental Benefits and Disadvantages of Economic Specialisation Within Global Markets, and Implications For SCP Monitoringdexfer_01Noch keine Bewertungen

- Irfan y 2017Dokument25 SeitenIrfan y 2017Judith Abisinia MaldonadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Green Techno Economy Based PolicyDokument18 SeitenGreen Techno Economy Based Policyrizky apNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.1 Background of The Study: Et Al (2018) Was Elaborate That The Time Trends For Countries and The World Have StayedDokument5 Seiten1.1 Background of The Study: Et Al (2018) Was Elaborate That The Time Trends For Countries and The World Have StayedIrfan UllahNoch keine Bewertungen

- NREE Chapter IIDokument23 SeitenNREE Chapter IIAbush SisayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filippini2020 The Effect of Culture On Energy Efficient Vehicle OwnershipDokument42 SeitenFilippini2020 The Effect of Culture On Energy Efficient Vehicle OwnershipRaul MJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Haas - Et - Al-2015-Journal - of - Industrial - Ecology How Circular Is The Global EconomyDokument13 SeitenHaas - Et - Al-2015-Journal - of - Industrial - Ecology How Circular Is The Global EconomyCPSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Pol Back On Course Production Final 060709Dokument15 SeitenClimate Pol Back On Course Production Final 060709lfish664899Noch keine Bewertungen

- Follow The Carbon The Case For Neighborhood-Level Carbon FootprintsDokument10 SeitenFollow The Carbon The Case For Neighborhood-Level Carbon FootprintsDaniel Aldana CohenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Low Income HousingDokument18 SeitenLow Income HousingViata VieNoch keine Bewertungen

- MPRA Paper 97369Dokument19 SeitenMPRA Paper 97369Ahmad IluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reap Miup t01b Stefani Iva.Dokument2 SeitenReap Miup t01b Stefani Iva.Iva StefaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Cleaner Production: Murat Kucukvar, Gokhan Egilmez, Omer TatariDokument10 SeitenJournal of Cleaner Production: Murat Kucukvar, Gokhan Egilmez, Omer Tatarihyukkie1410Noch keine Bewertungen

- MPRA Paper 30238Dokument25 SeitenMPRA Paper 30238Warwa QaisarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 RRLDokument6 SeitenChapter 2 RRLDarwin PanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schor, J. B. (2005) - Sustainable Consumption and Worktime Reduction. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9 (1 2), 37-50 PDFDokument15 SeitenSchor, J. B. (2005) - Sustainable Consumption and Worktime Reduction. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9 (1 2), 37-50 PDFlcr89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Recent Trends in Industrial Waste Management PDFDokument22 SeitenRecent Trends in Industrial Waste Management PDFVivek YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Desarrollo Sostenible-ParanoiaDokument15 SeitenDesarrollo Sostenible-ParanoiaandymolioNoch keine Bewertungen

- SoumyanandaDokument20 SeitenSoumyanandaGertrude RosenNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Renewable Energy Trade Economic Growth On CO2 Emissions in ChinaDokument21 SeitenThe Impact of Renewable Energy Trade Economic Growth On CO2 Emissions in ChinaAbdur RehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critica EFDokument7 SeitenCritica EFMihai MihalacheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Enviromental Footprint WordDokument11 SeitenEnviromental Footprint WordFana TekleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shopping For Sustainability: Can Sustainable Consumption Promote Ecological Citizenship?Dokument18 SeitenShopping For Sustainability: Can Sustainable Consumption Promote Ecological Citizenship?ChaosmoZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advances in Green Economy and Sustainability: Introduction: April 2018Dokument21 SeitenAdvances in Green Economy and Sustainability: Introduction: April 2018Alifanda CahyanantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- NREE Chapter IIDokument28 SeitenNREE Chapter IIAbush SisayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amoo 2013Dokument17 SeitenAmoo 2013Humayun Kabir JimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Generating Revenue and Economic DevelopmentDokument6 SeitenGenerating Revenue and Economic DevelopmentialnabahinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Context Effects and Heterogeneity in Voluntary Carbon Offsetting A Choice Experiment in SwitzerlandDokument25 SeitenContext Effects and Heterogeneity in Voluntary Carbon Offsetting A Choice Experiment in SwitzerlandAbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Lifestyle Approach To US Energy Use and The Related CO2 EmissionsDokument12 SeitenConsumer Lifestyle Approach To US Energy Use and The Related CO2 EmissionsAmir JoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mini Project Rain GaugeDokument11 SeitenMini Project Rain Gaugeamin shukriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Are Urbanization, Industrialization and CO2 Emissions Cointegrated?Dokument30 SeitenAre Urbanization, Industrialization and CO2 Emissions Cointegrated?doctshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of Innovation Drivers Andbarriers in Support of Better PoliciesDokument130 SeitenAnalysis of Innovation Drivers Andbarriers in Support of Better PoliciesEKAI CenterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trends in Household Energy ConsumptionDokument21 SeitenTrends in Household Energy ConsumptionSiddhartha KoduruNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Environmental Accounting A PDFDokument10 SeitenThe Impact of Environmental Accounting A PDFkaren rojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Development: F.A.M. Lino, K.A.R. IsmailDokument9 SeitenEnvironmental Development: F.A.M. Lino, K.A.R. IsmailErick MeiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cooperative and Non-Cooperative Equilibrium Consumption Taxes in The Presence of Cross-Border PollutionDokument25 SeitenCooperative and Non-Cooperative Equilibrium Consumption Taxes in The Presence of Cross-Border PollutionDavid IoanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carbon Intensities of Economies From The Perspective of Learning CurvesDokument10 SeitenCarbon Intensities of Economies From The Perspective of Learning CurvesAida NayerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case 7Dokument18 SeitenCase 7VinitSinhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air Pollution Literature ReviewDokument4 SeitenAir Pollution Literature Reviewea86yezd100% (1)

- Sustainable Consumption Progress-Should We Be Proud or AlarmedDokument7 SeitenSustainable Consumption Progress-Should We Be Proud or AlarmedAlan Marcelo BarbosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lit Rev Trade and Climate - Ifo - 20220902Dokument37 SeitenLit Rev Trade and Climate - Ifo - 20220902Gabriel FelbermayrNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESST 3104 CC and AT 2021 Lecture 1 OVERVIEW OF ENERGYDokument62 SeitenESST 3104 CC and AT 2021 Lecture 1 OVERVIEW OF ENERGYRandy Ramadhar SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Climate Change and Government Initiatives On Climate Change in IndiaDokument10 SeitenImpact of Climate Change and Government Initiatives On Climate Change in IndiaBhatia JyotikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Household Energy Conservation Patterns: Evidence From GreeceDokument26 SeitenHousehold Energy Conservation Patterns: Evidence From GreeceGiorgos PardalisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Energy Policy: Xiaoling Zhang, Yue WangDokument9 SeitenEnergy Policy: Xiaoling Zhang, Yue WangHiqmaAuliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eprs Bri (2020) 659295 enDokument10 SeitenEprs Bri (2020) 659295 enAnny HoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Economics Literature ReviewDokument5 SeitenEnvironmental Economics Literature Reviewfgwuwoukg100% (1)

- Circular Economy, Industrial Ecology and Short Supply ChainVon EverandCircular Economy, Industrial Ecology and Short Supply ChainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Auci Vignani 2014 Stat ApplicataDokument22 SeitenAuci Vignani 2014 Stat ApplicataestevaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carbon Offsetting: Sustaining Consumption?: Doi:10.1068/a40345Dokument24 SeitenCarbon Offsetting: Sustaining Consumption?: Doi:10.1068/a40345Heather LovellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carbon Footprint 1Dokument11 SeitenCarbon Footprint 1DennisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Papers On Environmental Economics and SustainabilityDokument8 SeitenResearch Papers On Environmental Economics and Sustainabilityh02pbr0xNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handbook of Environmental Economics: Environmental Degradation and Institutional ResponsesVon EverandHandbook of Environmental Economics: Environmental Degradation and Institutional ResponsesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Industrial Symbiosis for the Circular Economy: Operational Experiences, Best Practices and Obstacles to a Collaborative Business ApproachVon EverandIndustrial Symbiosis for the Circular Economy: Operational Experiences, Best Practices and Obstacles to a Collaborative Business ApproachRoberta SalomoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Hazardous Area ClassificationDokument7 SeitenUnderstanding Hazardous Area ClassificationAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Piping Material For Hydrogen ServiceDokument4 SeitenPiping Material For Hydrogen ServiceALP69Noch keine Bewertungen

- Building Design GuideDokument11 SeitenBuilding Design GuideAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guide To Insulation Product Specifications November 2016Dokument26 SeitenGuide To Insulation Product Specifications November 2016AamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- BS09 0674 680Dokument7 SeitenBS09 0674 680AamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flare TypeDokument44 SeitenFlare TypeBre WirabumiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ammonia - OSH AnswersDokument7 SeitenAmmonia - OSH AnswersAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Dedicated Earth PitsDokument5 SeitenWhy Dedicated Earth PitsAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- EarthingDokument25 SeitenEarthingdeepak_gupta_pritiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Tool For Rist AssignmentDokument7 SeitenA Tool For Rist AssignmentYusuf SeyhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insulation GlossaryDokument32 SeitenInsulation GlossaryAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Satish Lele: Codes and StandardsDokument10 SeitenSatish Lele: Codes and StandardsAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guide To Insulation Product Specifications November 2016Dokument26 SeitenGuide To Insulation Product Specifications November 2016AamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motor 'Musts' For Demanding EnvironmentsDokument10 SeitenMotor 'Musts' For Demanding EnvironmentsAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakistani Channel FrequencyDokument7 SeitenPakistani Channel FrequencyAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definitions of Hazard AssessmentDokument12 SeitenDefinitions of Hazard AssessmentAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Set Up Free To Air Satellite TDokument4 SeitenSet Up Free To Air Satellite TAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dell Latitude 7000 Series: Elite Design and ReliabilityDokument2 SeitenDell Latitude 7000 Series: Elite Design and ReliabilityoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Explosion Protection TechniquesDokument1 SeiteExplosion Protection TechniquesAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk Rating & AssessmentDokument7 SeitenRisk Rating & AssessmentAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Where The Hazards LieDokument11 SeitenWhere The Hazards LieAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motor 'Musts' For Demanding EnvironmentsDokument10 SeitenMotor 'Musts' For Demanding EnvironmentsAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Set Up Free To Air Satellite TDokument4 SeitenSet Up Free To Air Satellite TAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- ATEX Weighbridge ApplicationsDokument3 SeitenATEX Weighbridge ApplicationsAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tech Note - Definitions of Classes and ZonesDokument7 SeitenTech Note - Definitions of Classes and ZonesAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- LT Executive Safety Ldrship ASSEDokument4 SeitenLT Executive Safety Ldrship ASSEAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dell Latitude 7000 Series: Elite Design and ReliabilityDokument2 SeitenDell Latitude 7000 Series: Elite Design and ReliabilityoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classifying Hazardous Areas ComplicatedDokument10 SeitenClassifying Hazardous Areas ComplicatedAamerMAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Directors-Employer's Safety ResponsibilitiesDokument10 SeitenDirectors-Employer's Safety ResponsibilitiesamvitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LNG 4 - Operational Integrity 7-3-09-Aacomments-Aug09Dokument8 SeitenLNG 4 - Operational Integrity 7-3-09-Aacomments-Aug09nangkarak8201Noch keine Bewertungen

- Green FinDokument33 SeitenGreen Finsajid bhattiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pitch Deck EzzingSolar 20160901 CompressedDokument20 SeitenPitch Deck EzzingSolar 20160901 CompressedVega MiauNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3mwp784 SMMDokument8 Seiten3mwp784 SMMAdrian Pop-DragutNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vinay Sharma-PipingDokument5 SeitenVinay Sharma-PipingVinay SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

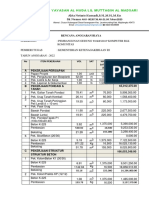

- Yayasan Al Huda Lil Muttaqin Al Madsari: Rencana Anggaran BiayaDokument6 SeitenYayasan Al Huda Lil Muttaqin Al Madsari: Rencana Anggaran BiayaMoja Januba ArifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- ! 13 OrcDokument16 Seiten! 13 Orcsapcuta16smenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Optimized Sponge Iron Making ProcessDokument10 SeitenOptimized Sponge Iron Making Processawneet_semc100% (1)

- NDV1200-2600 enDokument21 SeitenNDV1200-2600 enkolombo1776Noch keine Bewertungen

- Taking Manufacturing Further: Moving Into Vertical IntegrationDokument12 SeitenTaking Manufacturing Further: Moving Into Vertical IntegrationsnairmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sanyo MDF-U4186S Service ManualDokument30 SeitenSanyo MDF-U4186S Service ManualEmRe OflazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bemco BrochureDokument19 SeitenBemco BrochurelightsonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- African Review - August 2016Dokument86 SeitenAfrican Review - August 2016thewhitebunny6789Noch keine Bewertungen

- 201.28-Eg1 PDFDokument52 Seiten201.28-Eg1 PDFMr.K chNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Report On OIL and Gas INDUSTRYDokument18 SeitenFinal Report On OIL and Gas INDUSTRYShefali SalujaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nabcep PV Guide 7-16-13 WDokument160 SeitenNabcep PV Guide 7-16-13 Wradosting100% (1)

- Future-Proofing Fenders WhitepaperDokument9 SeitenFuture-Proofing Fenders WhitepaperShannel VendiolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pages From Research Report Dispersion Modelling and Calculation in Support of EI MCoSP Part 15 Mar 2008Dokument11 SeitenPages From Research Report Dispersion Modelling and Calculation in Support of EI MCoSP Part 15 Mar 2008Blake White0% (2)

- Menreg 41 PDFDokument6 SeitenMenreg 41 PDFBaher SalehNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Brief IFE and CPM Matrix Analysis Is As BelowDokument3 SeitenA Brief IFE and CPM Matrix Analysis Is As BelowAhmed Awais100% (2)

- B R 12345Dokument139 SeitenB R 12345rahmani bagherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jaipur Vidut Vitran Nigam LTD.: (A) Meter Reading & ConsumptionDokument1 SeiteJaipur Vidut Vitran Nigam LTD.: (A) Meter Reading & ConsumptionSangwan ParveshNoch keine Bewertungen

- HaverDokument8 SeitenHaverAlisha Chopra100% (1)

- SL Series IEC Vacuum Contactors TD en 6 2012Dokument22 SeitenSL Series IEC Vacuum Contactors TD en 6 2012rprojetos001tiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lscm-Oil and GasDokument3 SeitenLscm-Oil and GasUtkarsh KichluNoch keine Bewertungen

- NTPC1Dokument100 SeitenNTPC1Ram_Sandesh_Gu_4685100% (1)

- Etap Merging Library Addition 75Dokument2 SeitenEtap Merging Library Addition 75Hotmian SitinjakNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Electricity Investment On Inter-Regional Economic Development in Indonesia: An Inter-Regional Input-Output (IRIO) ApproachDokument12 SeitenThe Impact of Electricity Investment On Inter-Regional Economic Development in Indonesia: An Inter-Regional Input-Output (IRIO) ApproachFahrizal TaufiqqurrachmanNoch keine Bewertungen