Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

School Bus Case Consulting

Hochgeladen von

amitiiftdCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

School Bus Case Consulting

Hochgeladen von

amitiiftdCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Service options

Most state governments generally require their school districts to provide transportation to and

from schools. The federal government does not require transportation except as part of another

program.

Each school district has two basic options to provide transportation service to their students. Under

the first option, it may assume the responsibility of providing the transportation itself. The school

district purchases and maintains the equipment, sets the routes, and covers all functions described

above - in addition to teaching, counselling, and supporting all the other administrative activities

associated with education.

The second option is to contract with a private student transportation provider. With this option,

districts find a contractor and arrangement that best suited the needs of their community. Typical

contract elements include:

Vehicles: May be owned by a contractor or the school district.

Facilities: May be owned by or leased from the school district, or they may be owned and operated

by a contractor exclusively.

Staff: Generally employed by the contractor, there are some hybrid situations where employees

may continue to be employed by the school district or a third-party firm (employee leasing).

School bus variations

Against the backdrop of this brief account of the evolution of the school bus, it is worthwhile to

examine more closely some particular features. It is important to note that while all school buses

must be built to federal standards, not all school buses are alike. On top of the federal standards,

each state imposes its own set of regulations; so a school bus built for use in New York is different

from a school bus built for use in New Mexico. Sometimes the variations are a reflection of different

operating conditions. For example, a Southern state may require white roofs to reflect the suns

heat, while a Mountain state may require brake retarders. In other cases, a state may impose an

additional safety feature that the federal government has determined does not meet the

cost/benefit test for a mandate. Finally, individual bus owners may add a third layer of features to

satisfy contract requirements or personal preferences. No matter what the buses look like in the

end, they all start out as the basic federal school bus which is the safest vehicle on the road.

School bus types

There is more than one basic federal school bus. Following is a list of distinguishing characteristics of

the three common types:

Type A: The Type A bus is built on a van-style chassis, with a left-side drivers door. It is often

referred to as a mini school bus, and in its most common configuration carries 16 to 30 passengers.

It is popular for specialized transportation, including students with disabilities, and for routes that

are inaccessible to full-size buses.

Type C: Also known as the conventional bus, the Type C bus is the most recognizable. It has the

common hood configuration, with the door behind the front wheels, and is usually built to

accommodate 36 to 72 passengers.

Type D: The Type D bus is shaped like a transit bus, with a flat front and the entry door in front of the

wheels. It is the largest type and can be built for up to 90 passengers. Which school bus type is

better depends on the needs of the operator carrier.

Green Technology

The EPA standards that took effect in 2007 and 2010 have resulted in school buses that run 95%

cleaner than their older counterparts. Most school buses still run on diesel fuel, but now it is ultra

low sulfur diesel fuel in clean diesel engines. Older buses can be retrofitted with devices such as

particulate traps and diesel oxidation catalysts to reduce exhaust emissions, making them almost as

clean as new buses; and many contractors have taken advantage of grants from EPA or their state

clean air agencies to upgrade their buses. An increasing number of contractors are using biodiesel

fuel in their buses. This fuel, made from natural sources such as animal fats and vegetable oils, can

be blended in small proportions (up to 20%) with petroleum diesel for use in most engines without

modification. It provides a small reduction both in harmful emissions and in our reliance on fossil

fuels. Alternative-fuel school buses are gaining acceptance as well. Compressed natural gas (CNG)

buses are popular in districts where the infrastructure is available to support them, especially when

grants can help with the purchase price. Natural gas is often less expensive than diesel fuel, but the

initial cost of a CNG bus is much higher than a clean diesel bus, and the infrastructure is costly to

install. Hybrid-electric buses continue to gain acceptance since a separate fueling infrastructure is

not required. The cost however still remains prohibitive for some, thereby slowing adoption.

Propane is another alternative for clean buses, though not as popular as CNG. Propane also needs

additional fueling infrastructure, and requires particular safety training and facility accommodations.

One way all school bus fleets can reduce their environmental impact is by limiting idling time. Many

contractors have installed idle reduction technology, such as engine heaters, in their fleets. This

technology eliminates the need to start buses early in cold weather and to run them during wait

times. Even without additional devices, most carriers have reduced school bus idling through driver

and technician training and working with school administrators to implement procedures that will

limit the need for buses to idle.

Contracting

Contracting has proven to be successful in almost all cases where schools have partnered with

private companies to provide transportation. School administrators who convert to contracted

transportation increase their control by redirecting both energies and resources to their core

function: education. While districts contract transportation services for a variety of reasons, most

fall into one of the following categories:

The district fleet is aged, and funding is not available to upgrade it.

New equipment regulations, or safety/environmental innovations make new buses desirable, but

district funding or regulations limit turnover of the fleet.

Transportation cost increases have outpaced funding.

Economies of scale are not available, and benchmarked transportation costs exceed those for

familiar districts.

System inefficiencies have resulted in overextended resources and scheduling difficulties.

Federal, state and administrative changes (redistricting, addition of inter district magnet schools,

parental choice prerogatives) challenge the system.

Administrative headaches (dealing with parents, employee absenteeism, drug and alcohol testing,

mandated paperwork) require an inordinate share of administrators time and attention

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Intro To OLTP and OLAPDokument19 SeitenIntro To OLTP and OLAPamitiiftdNoch keine Bewertungen

- DurexDokument11 SeitenDurexamitiiftdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sales and Distribution Management of Durex in India: Overcoming Perception ChallengesDokument11 SeitenSales and Distribution Management of Durex in India: Overcoming Perception ChallengesamitiiftdNoch keine Bewertungen

- ITAM-Excel CasesDokument21 SeitenITAM-Excel CasesamitiiftdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Airtel Marketplace Connect Rural Buyers Sellers Under 40 CharactersDokument5 SeitenAirtel Marketplace Connect Rural Buyers Sellers Under 40 CharactersamitiiftdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sales and Distribution Management of Durex in India: Overcoming Perception ChallengesDokument11 SeitenSales and Distribution Management of Durex in India: Overcoming Perception ChallengesamitiiftdNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Straight and Crooked ThinkingDokument208 SeitenStraight and Crooked Thinkingmekhanic0% (1)

- The First, First ResponderDokument26 SeitenThe First, First ResponderJose Enrique Patron GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simple Present: Positive SentencesDokument16 SeitenSimple Present: Positive SentencesPablo Chávez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- This Content Downloaded From 181.65.56.6 On Mon, 12 Oct 2020 21:09:21 UTCDokument23 SeitenThis Content Downloaded From 181.65.56.6 On Mon, 12 Oct 2020 21:09:21 UTCDennys VirhuezNoch keine Bewertungen

- AZ 104 - Exam Topics Testlet 07182023Dokument28 SeitenAZ 104 - Exam Topics Testlet 07182023vincent_phlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kotak ProposalDokument5 SeitenKotak ProposalAmit SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH08 Location StrategyDokument45 SeitenCH08 Location StrategyfatinS100% (5)

- Social Media Audience Research (To Use The Template, Click The "File" Tab and Select "Make A Copy" From The Drop-Down Menu)Dokument7 SeitenSocial Media Audience Research (To Use The Template, Click The "File" Tab and Select "Make A Copy" From The Drop-Down Menu)Jakob OkeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pennycook Plagiarims PresentationDokument15 SeitenPennycook Plagiarims Presentationtsara90Noch keine Bewertungen

- FINPLAN Case Study: Safa Dhouha HAMMOU Mohamed Bassam BEN TICHADokument6 SeitenFINPLAN Case Study: Safa Dhouha HAMMOU Mohamed Bassam BEN TICHAKhaled HAMMOUNoch keine Bewertungen

- A History of Oracle Cards in Relation To The Burning Serpent OracleDokument21 SeitenA History of Oracle Cards in Relation To The Burning Serpent OracleGiancarloKindSchmidNoch keine Bewertungen

- KATU Investigates: Shelter Operation Costs in OregonDokument1 SeiteKATU Investigates: Shelter Operation Costs in OregoncgiardinelliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family RelationshipsDokument4 SeitenFamily RelationshipsPatricia HastingsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prospero'sDokument228 SeitenProspero'sIrina DraganescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Navarro v. SolidumDokument6 SeitenNavarro v. SolidumJackelyn GremioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing The Law The Legal Aspects of Doing Business 3rd Edition Mcinnes Test BankDokument19 SeitenManaging The Law The Legal Aspects of Doing Business 3rd Edition Mcinnes Test Banksoutacheayen9ljj100% (22)

- 27793482Dokument20 Seiten27793482Asfandyar DurraniNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Conference GREDIT 2016Dokument1 SeiteInternational Conference GREDIT 2016Οδυσσεας ΚοψιδαςNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Final Suggestion - HSC - 2013Dokument8 SeitenEnglish Final Suggestion - HSC - 2013Jaman Palash (MSP)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Symptomatic-Asymptomatic - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediaDokument4 SeitenSymptomatic-Asymptomatic - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediaNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Finals ReviewerDokument4 SeitenFinals ReviewerElmer Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- English JAMB Questions and Answers 2023Dokument5 SeitenEnglish JAMB Questions and Answers 2023Samuel BlessNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDokument5 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Human Person As An Embodied SpiritDokument8 SeitenThe Human Person As An Embodied SpiritDrew TamposNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Tendering - A Global Due Diligence Guide - 2021 EditionDokument2.597 SeitenThe Art of Tendering - A Global Due Diligence Guide - 2021 EditionFrancisco ParedesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guide to Sentence Inversion in EnglishDokument2 SeitenGuide to Sentence Inversion in EnglishMarina MilosevicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting Exclusive BreastfeedingDokument7 SeitenFactors Affecting Exclusive BreastfeedingPuput Dwi PuspitasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Virgin Atlantic Strategic Management (The Branson Effect and Employee Positioning)Dokument23 SeitenVirgin Atlantic Strategic Management (The Branson Effect and Employee Positioning)Enoch ObatundeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0 - Dist Officers List 20.03.2021Dokument4 Seiten0 - Dist Officers List 20.03.2021srimanraju vbNoch keine Bewertungen

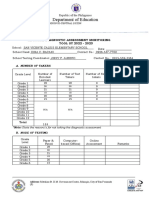

- Regional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Dokument3 SeitenRegional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Dina BacaniNoch keine Bewertungen