Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Verdun 1916

Hochgeladen von

Luciana IrustaOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Verdun 1916

Hochgeladen von

Luciana IrustaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

BATTLEFIELD

Verdun, 1916

Confict archaeologist Matt Leonard takes us

underground on the terrible battlefeld of Verdun.

T

he full horror of 20th century industrialised

warfare was nowhere more intense than

at Verdun in 1916. A French and German

battlefield, it is rarely visited by other

nationalities. Considering it is the key to

understanding the huge loss of life on the

Somme, this is a strange feature of modern battlefield tourism.

To the French, Verdun is sacred. A French city since the Peace

of Munich in 1648, it survived numerous attempts to capture it,

not least during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871. The rich

history of Verdun endowed it with mythic status in the French

psyche, a fact known to Von Falkenhayn when he launched his

siege in February 1916. The German Commander-in-Chief knew

that the French would never abandon Verdun and would hurl

every soldier at Frances disposal into the furnace he was going to

create.

His plan was not actually to capture the city, but simply to kill as

many Frenchmen as possible. He would bleed France white. So

began one of the most savage struggles of the First World War, one

that claimed over a million casualties in under a year.

The ordeal of Verdun is even more deeply ingrained in the

French consciousness than the Somme is in the British. It was a

national struggle, a battle for the survival, the honour, and the

sacred heart of France.

Blasted landscape

The modern, industrial nature of the weaponry used in the Great

War meant that the landscape was changed forever; modern warfare

creates as well as destroys. Landscape is transformed, and this

transformation can be seen in its most extreme forms at Verdun.

Even today, much of the surrounding area is still off limits to the

public. Millions of unexploded shells still litter the forest floors. Signs

exclaiming INTERDIT VERBOTEN FORBIDDEN are commonplace,

and unlike elsewhere on the Western Front, visitors pay attention to

the warnings.

In parts, the earth was so shattered by high explosive, poisoned by

toxic gas, and infected with thousands of rotting corpses that even

today it will not bear life. The ground is simply grey, and it is doubtful

whether anything will grow there again. Everywhere, the brutal scars

of war are visible. But there is one place in particular that stands out

in this vast area of murdered nature: the Butte de Vauquois.

The Butte de Vauquois is located about 15 miles from Verdun.

Before the war, it was a large hill some 290m high. At its peak was

the small village of Vauquois, a peaceful place where 170 or so

inhabitants quietly went about their business. By the end of 1916,

all this had changed. Mine warfare on an unprecedented scale

had transformed the landscape as if by the hand of God. Today,

a visitor to Vauquois will see a small memorial, but no sign of the

Above An aerial view of Fort Douaumont at Verdun, showing the efect of

concentrated modern artillery-fre.

45 March 2011

Left Streets in

towns and villages

needed to be kept

clear of rubble to

facilitate military

movement in

frontline areas.

P

h

o

t

o

s

:

A

l

l

i

m

a

g

e

s

W

a

r

d

D

i

g

i

t

a

l

u

n

l

e

s

s

o

t

h

e

r

w

i

s

e

s

t

a

t

e

d

.

Militarytimes

Verdun

village. There are now two hills instead of one, the original having

been divided in two by a series of enormous mine craters: industrial

destruction on an unimaginable scale.

By 1916, the Butte de Vauquois had become an important

strategic position, as from the top all traffic to Verdun through

the Islettes pass could be monitored. The Germans had actually

taken the hill in 1914, and had immediately set about fortifying

it. By 1915, the Butte had already been bitterly fought over, and a

labyrinth had started to form under its bloody surface.

War underground

The Great War is defined by the stalemate of trench warfare, but

all along the Western Front, from Flanders to the Alps, a secret war

was waged underground. The armies of all sides looked for a way

around the bloody business of sending men over the top into the

storm of steel in No Mans Land. The idea was to annihilate the

enemy from beneath, allowing the infantry to rush forward and

occupy the shattered land unopposed.

First begun by the German 30th Pioneer Battalion in January

1915, the tunnel systems at Vauquois soon increased in complexity

as each side tried to outdo the other. Listening tunnels were

dug to intercept the enemys approaching diggers. Storerooms,

antechambers, subways, command centres, and multiple entrances

and exits were created.

The French initially had the harder task, as they were on a gentler

incline than the Germans, and had to dig vertically in order to

create shafts into the hill. They named these shafts after Paris Metro

stations, akin to the way that British soldiers named their trenches

Above Plan of the Battle of Verdun showing the early German gains. Vauquois lies

on the frontline just beyond the lef-hand edge of the map. Plan: Ward Digital.

www.military-times.co.uk 46

and tunnel systems after familiar locations, often with a heavy sense

of irony and sarcasm. The resulting labyrinths could support about

1,000 men on either side, each racing to immolate the enemy first.

On 14 May 1916, the Germans set off 60,000kg of explosives,

the largest mine to be detonated at the Butte. It created a massive

crater that today is some 80m in diameter and approximately 20m

deep. During the war, it would have been much deeper, but as the

years have passed, sediment has gathered and the area has grassed

over. Even so, this and the series of other craters chill the blood of

the visitor. Before the First World War, this sort of conflict landscape

would not have been seen anywhere on Earth, and even today it is

hard to comprehend.

Right The Battle of

Verdun lasted ten

months, claimed a

million casualties, and

transformed the

landscape forever. Men

lived and fought in a

shattered landscape of

churned-up earth and

murdered nature.

The shattered terrain at the Butte de

Vauquois, where exploding mines

remade the surface of the Earth in 1916.

P

h

o

t

o

:

M

a

t

t

L

e

o

n

a

r

d

March 2011

BATTLEFIELD

Violence, terror, and hatred are all encased in the butchered

landscape of the Butte. The author Jules Romains referred to

Vauquois as a heap of ruins stuffed with dead mens bones. It

was regarded by the French as the worst posting at Verdun, and

Verdun was regarded as the worst on the Western Front. Life

at Vauquois was so bad that during late 1917 a short-lived and

unofficial truce was declared between the two bitter enemies. The

fighting had become unbearable, and in the end, the Germans

tried to destroy the entire hill; a task that proved simply too great.

The Butte today

Much of the old Western Front has been regenerated for the

benefit of remembrance or tourism. This has led to many

examples of trenches and dugouts being recreated in a sanitised

and acceptable manner. The history that they portray and the

stories that they narrate are controlled and often dubious. At

Vauquois, the history is raw, savage, and unedited.

Apart from the growth of vegetation, the obvious clearance of

the detritus of battle, and the addition of sparse railings around

the vast craters, very little has changed at the site since the end

of the war. Barbed-wire emplacements, trenches, entrances to

tunnel systems, and the craters themselves tell the history of the

abominable events that took place on this hill almost a century ago

in a manner that few other First World War sites can.

On the first Sunday of every month tours are run inside what is

left of the hill. Beneath the giant craters are some 17km of tunnels

on multiple levels. It is possibly the most thought-provoking and

impressive tour that can be taken on the Western Front. The

visitor gains a glimpse into a frightening and alien troglodyte

world. The scale of the mining and counter-mining is hard to

comprehend as the visitor rides the small mine carts through the

claustrophobic and seemingly endless tunnels.

The 519 mines detonated mean that it is extremely difficult to

judge how many people lost their lives at Vauquois. Many men

would have been atomised by the force of the blasts. But it is

estimated that the site is the grave of at least 8,000 of the missing.

It is also an official historic monument. This protected status

means that the whole area can be seen in context. Many of the

mine craters overlap each other, creating a giant scar across the

landscape, and clearly define what happened at Vauquois. This

differs, for example, from the Lochnagar crater at La Boiselle on

the Somme. Here, only one of the mine craters from the 1 July

1916 remains.

The Butte de Vauquois is far more than just an old battlefield. It

is a shocking example of how modern warfare creates a terrifying

world through the destruction it wreaks. It marks the end of battles

that were fought on an open field for not much longer than a day.

In the 100 years between the Battles of Waterloo and Verdun,

warfare had changed immeasurably. Conflict was now waged

above, on, and below the ground, with hugely powerful weapons,

for months and years on end. Men lived and fought in the ground

like animals, and destroyed each other in vast numbers. By 1916,

industrial killing of both man and nature had become a norm.

The Butte de Vauquois stands as a symbol of just how barbaric

modern humans and modern warfare had become.

Mt

Source: Matt Leonard

Research student, University of Bristol

Below Trench system at Vauquois. The impenetrability of First World War

trench systems, and the static war of attrition they imposed on the contending

armies, triggered an underground war on an

unprecedented scale.

One of the rail-carts used to remove spoil from a

tunnel at Vauquois. First World War military

tunnelling was an industrial operation.

One of the entrances to the tunnel

system at the Butte de Vauquois.

P

h

o

t

o

s

:

M

a

t

t

L

e

o

n

a

r

d

Further information

At Verdun, the forts of Douaumont and Vaux are worth a visit, as is

the Verdun Museum (Memorial de Verdun), the reconstructed village

of Fleury, the Trench of Bayonets, and the ossuary at Douaumont.

Underground tours at the Butte de Vauquois take place on the frst

Sunday of each month between 9.30am and 12pm and on 1 and 8 May

each year between 10am and 6pm.

XXXXXXXXXXX

www.en.verdun-tourisme.com

XX

47 Militarytimes

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

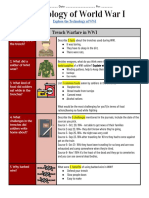

- Technology of WWI Worksheet - PooleDokument4 SeitenTechnology of WWI Worksheet - PooleAn NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Boer War by Doyle, Arthur Conan, Sir, 1859-1930Dokument381 SeitenThe Great Boer War by Doyle, Arthur Conan, Sir, 1859-1930Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of War in Peace 04Dokument224 SeitenThe Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of War in Peace 04AndersonArteNoch keine Bewertungen

- D Day Fact Sheet The SuppliesDokument1 SeiteD Day Fact Sheet The SuppliesmossyburgerNoch keine Bewertungen

- D Day OverviewDokument1 SeiteD Day OverviewThe State Newspaper100% (1)

- The Lucky Seventh in the Bulge: A Case Study for the Airland BattleVon EverandThe Lucky Seventh in the Bulge: A Case Study for the Airland BattleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air-Ground Teamwork On The Western Front - The Role Of The XIX Tactical Air Command During August 1944: [Illustrated Edition]Von EverandAir-Ground Teamwork On The Western Front - The Role Of The XIX Tactical Air Command During August 1944: [Illustrated Edition]Noch keine Bewertungen

- The History of Gaylordsville: John D. Flynn and Gaylordsville Historical SocietyVon EverandThe History of Gaylordsville: John D. Flynn and Gaylordsville Historical SocietyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wellington and Masséna Clash at Fuentes de OñoroDokument5 SeitenWellington and Masséna Clash at Fuentes de OñoroNicolas Junker100% (1)

- Why Gallipoli Matters: Interpreting Different Lessons From HistoryVon EverandWhy Gallipoli Matters: Interpreting Different Lessons From HistoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- JAPANESE IN BATTLE 1st Edition [Illustrated Edition]Von EverandJAPANESE IN BATTLE 1st Edition [Illustrated Edition]Noch keine Bewertungen

- Duffy's Regiment: A History of the Hastings and Prince Edward RegimentVon EverandDuffy's Regiment: A History of the Hastings and Prince Edward RegimentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Last Stand at Lang Son v0.6Dokument31 SeitenLast Stand at Lang Son v0.6Zebulon WhateleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ST Quentin CanalDokument13 SeitenST Quentin CanalIsrael GonçalvesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bluie West One: Secret Mission to Greenland, July 1941 — The Building of an American Air Force BaseVon EverandBluie West One: Secret Mission to Greenland, July 1941 — The Building of an American Air Force BaseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Above the Battle: An Air Observation Post Pilot at WarVon EverandAbove the Battle: An Air Observation Post Pilot at WarBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (1)

- TFH Engineer Group Newsletter Edition 5 130511Dokument33 SeitenTFH Engineer Group Newsletter Edition 5 130511Task Force Helmand Engineer GroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discovering my Father: The Wartime Experiences of Squadron Leader John Russell Collins DFC and Bar (1943-1944)Von EverandDiscovering my Father: The Wartime Experiences of Squadron Leader John Russell Collins DFC and Bar (1943-1944)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tobruk 1942: Rommel and the Battles Leading to His Greatest VictoryVon EverandTobruk 1942: Rommel and the Battles Leading to His Greatest VictoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- EW Rommel & Meuse ScenarioDokument4 SeitenEW Rommel & Meuse ScenarioelcordovezNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Eisenhower’s Battle For Control Of The Strategic Bombers In Support Of Operation OverlordVon EverandGeneral Eisenhower’s Battle For Control Of The Strategic Bombers In Support Of Operation OverlordNoch keine Bewertungen

- 14th Cavalry Group in World War II: Story of Cavalryman Bill Null: The Life and Death of George Smith Patton Jr., #3Von Everand14th Cavalry Group in World War II: Story of Cavalryman Bill Null: The Life and Death of George Smith Patton Jr., #3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shipping Company Losses of the Second World WarVon EverandShipping Company Losses of the Second World WarBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Kido Butai: The Battle of Midway ExplainedDokument6 SeitenKido Butai: The Battle of Midway ExplainedHong AhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy from the 15th Century to the PresentVon EverandShips of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy from the 15th Century to the PresentBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)

- Mons Myth: A Reassessment of the BattleVon EverandMons Myth: A Reassessment of the BattleBewertung: 1.5 von 5 Sternen1.5/5 (1)

- Jousting With Their Main Guns - A Bizarre Tank Battle of The Korean War - Arthur W Connor JRDokument2 SeitenJousting With Their Main Guns - A Bizarre Tank Battle of The Korean War - Arthur W Connor JRxtpr100% (1)

- The 'Blue Squadrons': The Spanish in the Luftwaffe, 1941-1944Von EverandThe 'Blue Squadrons': The Spanish in the Luftwaffe, 1941-1944Noch keine Bewertungen

- After Jutland: The Naval War in Northern European Waters, June 1916–November 1918Von EverandAfter Jutland: The Naval War in Northern European Waters, June 1916–November 1918Noch keine Bewertungen

- Royal Artillery Glossary: Historical and ModernVon EverandRoyal Artillery Glossary: Historical and ModernBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Winter War - Aerial WarfareDokument4 SeitenWinter War - Aerial WarfareToanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Battle of BalaclavaDokument14 SeitenBattle of BalaclavaJoseSilvaLeite100% (1)

- Covered With Mud And Glory: A Machine Gun Company In Action ("Ma Mitrailleuse")Von EverandCovered With Mud And Glory: A Machine Gun Company In Action ("Ma Mitrailleuse")Noch keine Bewertungen

- Destination Berchtesgaden: The US Seventh Army during World War IIVon EverandDestination Berchtesgaden: The US Seventh Army during World War IINoch keine Bewertungen

- WWI 1st Aero Squadron HistoryDokument18 SeitenWWI 1st Aero Squadron HistoryCAP History LibraryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Last Stand at Lang Son v0.8Dokument38 SeitenLast Stand at Lang Son v0.8Zebulon WhateleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ironside: The Authorised Biography of Field Marshal Lord IronsideVon EverandIronside: The Authorised Biography of Field Marshal Lord IronsideNoch keine Bewertungen

- Algeria, France's Undeclared WarDokument4 SeitenAlgeria, France's Undeclared WarMiles MartinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Birmingham Pals: 14th, 15th & 16th (Service) Battalions of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, A History of the Three City Battalions Raised in Birmingham in World War OneVon EverandBirmingham Pals: 14th, 15th & 16th (Service) Battalions of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, A History of the Three City Battalions Raised in Birmingham in World War OneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global War: A Month-by-Month History of World War IIVon EverandGlobal War: A Month-by-Month History of World War IINoch keine Bewertungen

- The Battle of France by Miles MathisDokument23 SeitenThe Battle of France by Miles MathislennysanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 'Fifteen Rounds a Minute': The Grenadiers at War, August to December 1914, Edited from Diaries and Letters of Major 'Ma' Jeffreys and OthersVon Everand'Fifteen Rounds a Minute': The Grenadiers at War, August to December 1914, Edited from Diaries and Letters of Major 'Ma' Jeffreys and OthersNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3rd Battalion 60th Infantry RegimentDokument2 Seiten3rd Battalion 60th Infantry RegimentRiverRaiders100% (1)

- WWII Historical Reenactment Society Jul 2011Dokument12 SeitenWWII Historical Reenactment Society Jul 2011CAP History LibraryNoch keine Bewertungen

- St. Petersburg Open 2017Dokument1 SeiteSt. Petersburg Open 2017Luciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moselle Open 2017 PDFDokument1 SeiteMoselle Open 2017 PDFLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mds PDFDokument1 SeiteMds PDFLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

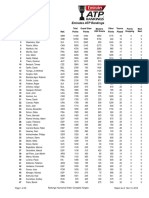

- Singles Emirates Atp Rankings NumericalDokument45 SeitenSingles Emirates Atp Rankings NumericaltractinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Western & Southern OpenDokument1 SeiteWestern & Southern OpenLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argentina Open Singles 2016Dokument1 SeiteArgentina Open Singles 2016Luciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

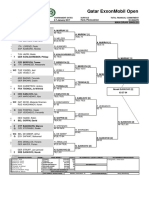

- Qatar ExxonMobil Open 2017 PDFDokument1 SeiteQatar ExxonMobil Open 2017 PDFLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moselle Open 2017 PDFDokument1 SeiteMoselle Open 2017 PDFLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moselle Open 2017 PDFDokument1 SeiteMoselle Open 2017 PDFLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qatar ExxonMobil Open PDFDokument1 SeiteQatar ExxonMobil Open PDFLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Singles Emirates Atp Rankings AlphabeticalDokument45 SeitenSingles Emirates Atp Rankings AlphabeticalLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brisbane InternationalDokument1 SeiteBrisbane InternationalLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argentina Open Singles 2016Dokument1 SeiteArgentina Open Singles 2016Luciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 2 PersonaValoresDokument19 Seiten1 2 PersonaValoresMaria Elena Alcantara VargasNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7th Forte Village International Tournament: ITF Men's CircuitDokument1 Seite7th Forte Village International Tournament: ITF Men's CircuitLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trofeul Municipiului Galati-Viva Club Open: ITF Men's CircuitDokument1 SeiteTrofeul Municipiului Galati-Viva Club Open: ITF Men's CircuitLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ivor Braka 2015: ITF Men's CircuitDokument1 SeiteIvor Braka 2015: ITF Men's CircuitLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

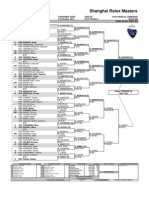

- Shanghai Rolex MastersDokument1 SeiteShanghai Rolex MastersLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sharm El Sheikh Men's Singles QualifyingDokument1 SeiteSharm El Sheikh Men's Singles QualifyingLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iii Copa Santiago Giraldo: ITF Men's CircuitDokument1 SeiteIii Copa Santiago Giraldo: ITF Men's CircuitLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TEB PNB Paribas Istanbul Open 2015Dokument1 SeiteTEB PNB Paribas Istanbul Open 2015Luciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argentina F5 Futures: ITF Men's CircuitDokument1 SeiteArgentina F5 Futures: ITF Men's CircuitLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argentina Open: Buenos Aires, Argentina 23 February-1 March 2015red Clay $573,750Dokument1 SeiteArgentina Open: Buenos Aires, Argentina 23 February-1 March 2015red Clay $573,750Luciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Algeria F2 Futures: ITF Men's CircuitDokument1 SeiteAlgeria F2 Futures: ITF Men's CircuitLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BNP Paribas Open: Indian Wells, USA 9-22 March 2015 Hard, Plexipave $5,381,235Dokument2 SeitenBNP Paribas Open: Indian Wells, USA 9-22 March 2015 Hard, Plexipave $5,381,235Luciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Miami, United States 23 March - 5 April 2015 Hard, Laykold $5,381,235Dokument2 SeitenMiami, United States 23 March - 5 April 2015 Hard, Laykold $5,381,235Luciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torneo Future Berimbau 2015: ITF Men's CircuitDokument1 SeiteTorneo Future Berimbau 2015: ITF Men's CircuitLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shanghai Rolex Master 2014Dokument1 SeiteShanghai Rolex Master 2014Luciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monte-Carlo Rolex MastersDokument1 SeiteMonte-Carlo Rolex MastersLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutua Madrid Open Order of PlayDokument1 SeiteMutua Madrid Open Order of PlayLuciana IrustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Luring Lolita: The Age of Consent and The Burden of Responsibility For Online LuringDokument11 SeitenLuring Lolita: The Age of Consent and The Burden of Responsibility For Online LuringAndrea SlaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Women Deserve To Be Raped: From Delhi PoliceDokument13 SeitenWhy Women Deserve To Be Raped: From Delhi PoliceMisbah ul Islam AndrabiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dissertation Topics Around Domestic ViolenceDokument7 SeitenDissertation Topics Around Domestic ViolenceBuySchoolPapersOnlineSingapore100% (1)

- Im Health 7 Intentional InjuryDokument41 SeitenIm Health 7 Intentional InjuryLouis CarterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Report On The Winnipeg Police Service Flight Operations UnitDokument18 SeitenFull Report On The Winnipeg Police Service Flight Operations UnitRileyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Burger Machine T-Shirt Leads to Rapist's ArrestDokument6 SeitenBurger Machine T-Shirt Leads to Rapist's ArrestJason ToddNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Wild ReleaseDokument6 Seiten6 Wild ReleaseChristopher RobbinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- AWH Harassment PolicyDokument4 SeitenAWH Harassment Policy210patchesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statements Released by Gloria Allred and Shantel JacksonDokument8 SeitenStatements Released by Gloria Allred and Shantel JacksonDeadspin100% (1)

- Criminal liability in the workplaceDokument15 SeitenCriminal liability in the workplaceJUNAID FAIZANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toye-Rial MTN For Leave To Conduct DiscoveryDokument188 SeitenToye-Rial MTN For Leave To Conduct DiscoveryAnonymous RtqI2MNoch keine Bewertungen

- S Upreme Qcourt: L/Epublic of Tbe FfianilaDokument20 SeitenS Upreme Qcourt: L/Epublic of Tbe FfianilaJJ Pernitez100% (1)

- People V Chua HiongDokument2 SeitenPeople V Chua HiongAndrea Juarez100% (2)

- Criminal Law 1 Review: By: John Mark N. Paracad Legal Officer, DENR Region IIDokument163 SeitenCriminal Law 1 Review: By: John Mark N. Paracad Legal Officer, DENR Region IIJohn Mark ParacadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aggravating Circumstances 9 23 04Dokument7 SeitenAggravating Circumstances 9 23 04SuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wayne County Prosecutor News Updates April 13 - April 19Dokument5 SeitenWayne County Prosecutor News Updates April 13 - April 19Crime in DetroitNoch keine Bewertungen

- IELTS Vocabulary CrimeDokument2 SeitenIELTS Vocabulary CrimeMunirathnamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Redacted Police Report of Client From Kevin CarrollDokument2 SeitenRedacted Police Report of Client From Kevin CarrollDaily Caller News FoundationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Right To Private Defence of BodyDokument19 SeitenRight To Private Defence of Bodylegalight50% (2)

- 4.1 - Dread Metrol (Player Guide)Dokument34 Seiten4.1 - Dread Metrol (Player Guide)Chris NolanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bandidos IndictmentDokument28 SeitenBandidos IndictmentHouston ChronicleNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. MacariolaDokument2 SeitenPeople vs. MacariolaInean TolentinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 281 Other Forms of Trespass (Trespass To Prop)Dokument19 Seiten281 Other Forms of Trespass (Trespass To Prop)Abby ParaisoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Charlevoix County News, September 15, 2011Dokument18 SeitenCharlevoix County News, September 15, 2011Dave BaragreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs Bulos Rape Case RulingDokument1 SeitePeople vs Bulos Rape Case RulingEllaine VirayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tehelka in Crisis: 1. SummaryDokument3 SeitenTehelka in Crisis: 1. SummarykaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- ScawbyturnDokument1 SeiteScawbyturnSelina MaycockNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thomas Evans Sentencing MemorandumDokument12 SeitenThomas Evans Sentencing MemorandumABC News 4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arraignment and PleaDokument51 SeitenArraignment and PleaDe Guzman E AldrinNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 M2ri Shakthe Sharavana KumaarDokument63 Seiten2015 M2ri Shakthe Sharavana KumaarKrishnaNoch keine Bewertungen

![Air-Ground Teamwork On The Western Front - The Role Of The XIX Tactical Air Command During August 1944: [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259895642/149x198/ac23a1ff63/1617227775?v=1)

![JAPANESE IN BATTLE 1st Edition [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259898586/149x198/d941828316/1617227775?v=1)

![The AAF In Northwest Africa [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259895534/149x198/00a791248f/1617227774?v=1)