Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Marriage As A Special Contract

Hochgeladen von

Zypress AcacioOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Marriage As A Special Contract

Hochgeladen von

Zypress AcacioCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

MARRIAGE AS A SPECIAL CONTRACT

Article 1 of the Executive Order No. 209, otherwise known as the Family Code defines marriage as a special contract

of permanent union entered into in accordance with law for the establishment of conjugal and family life. It is a special

contract because it is more than a mere contract accompanied by duties and obligations unique to a married life.

The consent of the parties is essential to its existence like any other contract. However, when the contract to marry is

executed by a man and a wife, a relation between the parties is created which they cannot change except for special

circumstances as will be discussed later. Other contracts may be modified, restricted or enlarged or entirely released

from upon the will of the parties. Not so with marriage. The relation, once formed, calls for the law to step in and hold

the parties to various obligations and liabilities. Marriage is a special contract also because it is vested with public

interest. Marriage is an institution in the maintenance of which in its purity the public is deeply interested for it is the

foundation of the family and of society- without which there would be neither civilization nor progress87. It is the

characteristic of permanence therefore that distinguishes marriage from a purely consensual transaction.

Marriage is also a civil contract, such that no ecclesiastical elements are involved. The law does not look upon

marriage as a sacrament. In the eyes of the law, marriage is a secular matter. When the requirements of law are

complied with, what has been entered, is by law, a contract of marriage, whatever else a church or a religious

organization may demand from its members.

Marriage can be argued to be the very groundwork for other domestic relations. The state has an interest in this

special contract. Marriage is the foundation of the family, and around the family, many of our present day social

institutions are built.

Extrinsic Validity

In the Philippines, the determination of the extrinsic validity of marriage is referred to the lex loci celebrationis, or, law

of the place of celebration. This is a consequence of the maxim locus regit actum, or the place governs the act. By

extrinsic validity, we mean the legal sufficiency insofar as the formal requisites of a valid marriage are concerned.

Story the general principle is that between persons, sui juris, the validity of a marriage is to be decided by the law of

the place where it is celebrated. If the marriage is valid in the place of celebration, it is valid everywhere. In the same

line of thought, if the marriage is invalid in the place of celebration, it is invalid everywhere.

The Hague Convention on Celebration and Recognition of the Validity of Marriages89, states that the formal

requirements for marriage are governed by the law of the state of celebration, a reiteration of a recognized principle

of conflict of laws. Hence, the general rule is that all states recognize as valid marriages celebrated in foreign

countries if they complied with the formalities prescribed there.

Ernst Rabel made a comparative survey of various legal systems revealing that there are three ways of applying the

maxim locus regit actum:

The imperative or compulsory rule.

In one group of countries, including the United States, England, Denmark, Japan and the Philippines, the law of the

place where the marriage is celebrated governs the matter of formal validity, irrespective of whether the marriage is

concluded within or outside the forum. In short, the maxim locus regit actum or the principle that the act is governed

by the law of the place where it is done is applied compulsorily; the law of the place of celebration, the lex loci

celebrationis, is solely decisive.

The optional rule.

Many countries follow the optional ruleparties celebrating a marriage within the forum must comply with domestic

formalities; parties marrying abroad must observe either the formalities prescribed at the place of celebration or those

of the personal law of the parties. Article 7 of the Hague Convention on marriage adopts the optional rule by providing

that where the parties to a marriage are of different nationalities, a marriage not complying with the formal

requirements in the country of celebration must satisfy the national laws of both parties in order to be recognized by

other participating states.

The modified or religious method

This method is adopted by a few countries, notably, Greece, Egypt, and Spain, insofar as Spanish Catholics are

concerned due to its distinctive premium on religious custom. The rule may be modified by considering the religious

form prescribed by law of these countries as essential for marriage of their own nationality. A marriage by merely civil

ceremony performed abroad may not be recognized in the forum.

Sources of Law

The Philippines abide by the imperative rule. For marriages celebrated outside the Philippines,

Article 17 of the Civil Code embodying the rule locus regit actum, or les loci celebrationis, govern: The forms and

solemnities of contracts, wills, and other public instruments shall be governed by the laws of the country in which they

are executed. For marriages celebrated in the Philippines, the formal requirements are set forth in Article 3 of the

Family Code. - 1. Authority of the solemnizing officer; 2. A valid marriage license expect in cases provided in Chapter

2 of this Title; and 3. A marriage ceremony which takes place with the appearance of the contracting parties before

the solemnizing officer and their personal declaration that they take each other as husband and wife in the presence

of not less than two witnesses of legal age.

JURISDICTION AND CHOICE OF LAW

The lex loci celebrationis principle is expressed in the first paragraph of Article 26 of the

Family Code, which states that: All marriages solemnized outside the Philippines, in accordance with the laws in

force in the country where they were solemnized, and valid there as such, shall be valid in this country, except those

prohibited under Articles 35(1) (4) (5) 36, 37 and 38.

Intrinsic Validity

Intrinsic validity relates refers to the legal sufficiency insofar as the substantive requirements of a valid marriage are

concerned, including the general capacity of the contracting parties. However, each legal system possesses a distinct

concept of what matters are of substance as distinguished from what matters are of form. A survey of the various

legal system demonstrates that there are two competing principles as to the law that should govern the substantive

validity of marriage. One points to lex loci celebrationis while the other direction refers to the personal law of the

contracting parties, either by the parties personal laws, which may either be their domicile or nationality.

It is said that the principle that would govern the intrinsic validity of a marriage depends on the policies and treatment

of marriage of a particular legal system. Where marriage is considered a contract, lex loci celebrationis prevails; while

if considered primarily as a status or an institution, it is the law of their domicile or their nationality that is controlling.

In the United States of America, the usual view is that a marriage valid where entered is valid anywhere. The Second

Restatement provides that a marriage, which satisfies the requirements of the State where contracted, will be

recognized everywhere as valid unless it violates the strong public policy of another State which has the most

significant relationship to the spouses and the marriage at the time of the marriage. Thus, marriages that are

contracted by parties forbidden to marry, or forbidden to enter the particular marriage in question, of those which are

polygamous or incestuous are denied validity.

Sources of Law

Marriages between Filipino Citizens, no matter where celebrated, are valid if it complies with the requirements of

Article 2 of the Family Code, which states that: No marriage shall be valid, unless these essential requisites are

present: Legal capacity of the contracting parties who must be a male and a female; and Consent freely given in the

presence of the solemnizing officer.

JURISDICTION AND CHOICE OF LAW

Philippine law on substantive validity does not exclusively adhere to the lex loci celebrationis rule. There is a

distinction as to marriages celebrated abroad, and in respect to marriages in the Philippines. As to the former, what

applies is a combination of the lex loci celebrationis rule and the personal law (national law) rule. This is clearly the

meaning of Article 26 of the Family Code. This general rule should therefore be qualified by two exceptions. First,

marriage between Filipino nationals who marry abroad before the Philippine consular or diplomatic officials, in which

case whatever the law of the place of the celebration prescribes, the substantive validity is to be determined by

Philippine laws. Secondly, the saving clause of Article 26, declaring as invalid marriages prohibited under Philippine

laws by reason of public policy, including polygamous, incestuous marriages and those contracted through mistake.

As to marriages entered into in the Philippines, the national law of the party concerned insofar as his capacity to

contract marriage is concerned is decisive. Corollary to this, Article 21 of the Family Code requires that aliens must

submit a certificate of legal capacity to contract marriage issued by their respective diplomatic or consular officials,

before they can be issued a marriage license.

Marriage by Proxy

A marriage by proxy is one where one of the parties is merely represented at the ceremony by a friend or delegate.

The following are the rules governing such a marriage: If celebrated in the Philippines the marriage is void. Article

6 of the Family Code requires the presence of both parties. It is said however that the rule holds true only in cases

where the marriage is between Filipinos or between a Filipino and a foreigner. In case the contracting parties are both

foreigners, then it would be a valid marriage provided their national law considers is such. It should be noted also that

the place where the proxy appears is considered where the marriage is celebrated. If celebrated abroad the rule is

lex loci celebrationis, whether the marriage is between Filipinos, foreigners or mixed. This is of course subject to the

usual exceptions (highly immoral etc.) and subject to special provisions as may be found in special laws (e.g.,

immigration laws for purpose of immigration).

Rules on Marriage as a Status

FACTUAL SITUATION POINT OF CONTACT

1 Personal rights & obligations between

husband & wife

National of husband

(Note: Effect of subsequent change of

nationality:

1. If both will have a new nationality

the new one

2. If only one will change the last

common nationality

3. If no common nationality

nationality of husband at the time

FACTUAL SITUATION POINT OF CONTACT

Celebrated

Abroad

Between Filipinos Lex loci celebrationis is without prejudice to

the exceptions under Articles 25, 35 (1, 4, 5

& 6), 36, 37 & 38 of the Family Code

(bigamous & incestuous marriages) &

consular marriages

Between Foreigners Lex loci celebrationis EXCEPT if the

marriage is:

1. Highly immoral (like bigamous/

polygamous marriages)

2. Universally considered incestuous

(between brother-sister, and

ascendants-descendants)

Mixed Apply 1 (b) to uphold validity of marriage

Celebrated

in RP

Between Foreigners National law (Article 21, FC) PROVIDED

the marriage is not highly immoral or

universally considered incestuous)

Mixed National law of Filipino (otherwise public

policy may be militated against)

Marriage by proxy (NOTE: a marriage by

proxy is considered celebrated where the

proxy appears

Lex loci celebrationis (with prejudice to the

foregoing rules)

of wedding)

2 Property relations bet husband & wife National law of husband without prejudice

to what the CC provides concerning REAL

property located in the RP (Article 80)

(NOTE: Change of nationality has NO

EFFECT. This is the DOCTRINE OF

IMMUTABILITY IN THE

MATRIMONIAL PROPERTY

REGIME)

MARRIAGE AS STATUS

The resultant relationship between a man and a woman who entered in a contract of marriage is one of personal

status. This status is created and destroyed by law and not by mere consent of the parties, and is of legal importance

to all the world. Marriage therefore creates social status or relation between the contracting parties in which not only

they but the state are interested and involves a personal union of those participating in it of a character unknown to

any human relations, and having more to do with the morals and civilization of people than any other institution.92 And

whenever a peculiar status is assigned by law to members of any particular class of persons, affecting their general

position in or with regard to the rest of the community, no one belonging to such class can vary by any contract the

rights and liabilities incident to this status.

Marriage as a status carries with it implications in two fields: the realm of personal rights and obligations of the

spouses, which is a filed of personal affair between the husband and wife and as such will not ordinarily be interfered

with by the courts of justice; and the realm of property relations, to which several judicial sanctions are applicable.

PERSONAL RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS

In our jurisdiction, the national law of the parties governs personal relations between the spouses. Thus, Article 15 of

the Civil Code states, Laws relating to family rights and duties, or to the status, condition and legal capacity of

persons are binding upon citizens of the Philippines, even though living abroad.

PROPERTY RELATIONS AND MARRIAGE

Marital Property Relations in the Philippines

The pertinent provision regarding the property relations that govern between husband and wife in the Philippines can

be found in Title IV of the Family Code, particularly in the General Provisions found in Chapter 1 of the same Title.

Art. 74. The property relationship between husband and wife shall be governed in the following order:

(1) By marriage settlements executed before the marriage;

(2) By the provisions of this Code; and

(3) By the local custom.

The law recognizes that the property relation between spouses may be set by express agreement through a proper

and valid marriage settlement. Article 77 prescribes the conditions for the validity of a marriage settlement that it must

be in writing, signed by the parties, and made prior to the celebration of marriage. Generally the parties may stipulate

or agree to any arrangement in the marriage settlement for as long as it is not contrary to law and public policy and is

within the limits provided for in the Family Code.

Article 91 states that the absolute community property regime encompasses all the property owned by the spouses

at the time of the celebration of the marriage or acquired thereafter. Art 93 further provides that a presumption exists

that all property acquired during the marriage belongs to the absolute community.

Under the Conjugal Partnership of Gains regime 109 , the spouses place in a common fund the proceeds, products,

fruit and income from their separate properties, through effort or chance. In the event of dissolution of the marriage or

partnership, the benefit that accrued to the spouses shall be divided equally between them, unless otherwise stated

in the marriage settlement.

The third property regime is called the regime of Separation of Property in which case each spouse shall own,

dispose of, possess, administer and enjoy his or her own separate estate, without need of the consent of the other

Conflict of law problems arising from the property of the spouses are easily disposed of when there is a marriage

settlement that has been executed by the parties. But how does one face the same problem in the absence of such

settlement? The same Title and Chapter on the General Provisions provide the answer in the form of Article 80.

Art. 80. In the absence of a contrary stipulation in a marriage settlement, the property relations of

the spouses shall be governed by Philippine laws, regardless of the place of the celebration of the

marriage and their residence. This rule shall not apply:

Where both spouses are aliens;

With respect to the extrinsic validity of contracts affecting property not situated in the Philippines and executed in the

country where the property is located; and

With respect to the extrinsic validity of contracts entered into in the Philippines but affecting property situated in a

foreign country whose laws require different formalities for its extrinsic validity. (124a)

The provision imposes the Philippine law in the absence of any agreement to the contrary where the contracting

parties are Filipino citizens. It further claims application even if the parties contracted marriage in another jurisdiction

or even if they decided to take up residence abroad. This takes into consideration Art 16 of the Civil Code of the

Philippines, the Situs Rule subjects the real and personal property to the law of the country where it is located or

situated.

The provision cites 3 exceptions when the Philippine law does not apply. First, the law defers application to

spouses who are both nationals of another state. Second, in case the parties entered into a contract which involves

properties abroad the extrinsic validity of such contract, whether executed here or abroad, will not be governed by

Philippine laws. And lastly, the law of the place where the property is situated outside the Philippines shall govern the

extrinsic validity of the contract entered into in the Philippines.

Article 80 seems to make reference only to the law of the place of the property concerned without distinction as to

whether the property involved is immovable or not. This is where we think Scoles' distinction between immovable and

movable property and his different treatment thereof would be helpful in filling the gaps in Art 80 of the Civil Code.

SCOPE OF PERSONAL RELATIONS BETWEEN THE HUSBAND AND THE WIFE

Personal rights and obligations between husband and the wife, all of which are generally governed by the national

law of the husband, but subject to the principles of characterization and to the exceptions to the application of proper

foreign law, include the following:

Mutual identity, cohabitation, and respect;

Mutual assistance and support;

Right of the wife to use the husbands name;

Duty of the wife to follow the husband to his residence or domicile.

Under Article 68 of the Family Code, the husband and wife are obliged to live together, observe mutual love, respect

and fidelity, and render mutual help and support.

Effect of Change of Nationality

If the husband will effect a subsequent change of nationality the following rules are believed applicable; If both the

husband and the wife will have a common nationality the new national law will govern their personal relations; If

only one will change nationality the common nationality will be applicable.

If there never was any common nationality the governing rule will be the national law of the husband at the time that

the marriage was entered into.

Duties of a Married Person

Duty to live together

Duty to observe mutual love and respect

Duty to observe mutual respect and fidelity

Duty to render mutual help and support

Procedure to Enforce Rights

To enforce rights granted by the husbands national law, resort is had to the lex fori, hence

should suits be litigated in the Philippines, our procedural rules will have to be followed.

Survey of jurisprudence related to the Recognition of the Inception of Marriage

Wong Woo Yu v. Vivo Thus, under Article 15 of our new Civil Code provides that family rights or to the status of

persons are binding upon citizens of the Philippines, even though living abroad, and it is well known that in 1929 in

order that a marriage celebrated in the Philippines may be valid, it must be solemnized either by a judge of any court

inferior to the Supreme Court, a justice of the peace, or a priest or minister of the gospel of any denomination duly

registered in the Philippine Library and Museum (Public Act 3412, Section 2).

Apt v. Apt If a marriage is good by the laws of the country where it is effected, it is good all the world over, no

matter whether the proceeding or ceremony which constituted marriage according to the law of the place would or

would not constitute marriage in the country of domicile of one or other of the spouses. If the so-called marriage is no

marriage in the place where it is celebrated, there is no marriage anywhere, although the ceremony or proceeding if

conducted in the place of the parties domicile would be considered a good marriage.

The contract of marriage in this case was celebrated in Buenos Aires; that the ceremony was performed strictly in

accordance with the law of that country; that the celebration of marriage by proxy is a matter of form of the ceremony

or proceeding, and not an essential of the marriage; that there is nothing abhorrent to Christian ideas in the adoption

of that form; and that, in the absence of legislation to the contrary, there is no doctrine of public policy which entitles

me to hold to that the ceremony, valid where it was performed, is not effective in this country to constitute a valid

marriage.

Sottomayor v. De Barros It is a well settled principle of law that the question of personal capacity to enter into

any contract is to be decided according to the law of the domicile.. the law of a country where a marriage is

solemnized must alone decide all questions relating to the validity of the ceremony by which the marriage is alleged

to have been constituted; but as in other contracts, so in that marriage, personal capacity must depend on the law of

the domicile, and if the laws of any country prohibits its subjects within certain degrees of consanguinity from

contracting marriage, and stamp a marriage between persons within the prohibited degrees as incestuous, this in our

opinion imposes on the subjects of that country a personal incapacity which contributes to affect them so long as they

are domiciled in that country where the law prevails, and renders invalid a marriage between persons, both a the time

of their marriage subjects of, and domiciled in the country which imposes the restriction wherever such marriage may

have been solemnized.

ANNULMENT AND DIVORCE

DIVORCE

Overview of divorce/ kinds of divorce

Divorce is the legal dissolution of the marriage bond rendered by a competent court for causes defined by law which

arose after marriage. It presupposes that marriage is valid. Generally, there are two kinds of divorce:

(1) absolute (divorce a vinculo matrimoniee) where marital ties are dissolved

and

(2) relative (divorce a mensaet thoro) where parties remain married although they are allowed to live separately from

each other. Upon the enactment of the Civil Code, absolute divorce was no longer recognized except under Article 26

of the Family code wherein a divorce validly obtained by foreign spouse against the Filipino spouse is recognized and

given effect and the latter is free to re-marry as an exception to the general rule and when obtained by alien spouses.

However, relative divorce or more known as legal separation is allowed as provided for under Article 55 of the Family

Code.

The importance in determining whether a decree of divorce is valid or not is to ascertain the status of the parties and

to fix and make certain the property rights and interest of the parties such as custody, care and support of the

children.

Philippine Conflicts Rule on Divorce

With the abolition of the absolute divorce under the Civil Code, the rule with reference to Filipino couples became

rigid and simple: as long as they are Filipino citizens, they cannot obtain a divorce decree abroad which would be

recognized in the Philippines. Likewise, Philippine courts are not available to aliens for the purpose of obtaining

absolute divorce decrees.

The rule on divorce in this jurisdiction was reiterated in the case of Tenchavez vs. Escano, as follows: The Civil Code

of the Philippines, now in force, does not admit absolute divorce, quo ad vinculo matrimonii; and in fact does not even

use that term, to further emphasize its restrictive policy on the matter, in contrast to the preceding legislation that

admitted absolute divorce on grounds of adultery of the wife or concubinage of the husband (Act No. 2710). Instead

of divorce, the present Civil Code only provides for legal separation (Title IV, Book I, Arts. 97 to 108), and, even in

that case, it expressly prescribes that bonds shall not be severed (Art. 106, subpar. 1). Although as a rule divorce is

not recognized in this jurisdiction, divorce is allowed in the following instances: between foreign spouses and by a

foreigner in his country or in a country which grants divorce, who is married to a Filipino citizen is recognized insofar

as the foreigner is concerned. As to the first instance wherein divorce is between foreign spouses, the Court

considers the absolute divorce between foreign spouse as valid and binding in the Philippines on the ground that the

status and dissolution of the marriage are governed by their national law except when they contravene the law or

public policy of the country. On the other hand, divorce legally obtained by foreign spouse against the Filipino spouse

is expressly provided for under the second paragraph of Article 26 of the Family Code: Where a marriage between a

Filipino citizen and a foreigner is validly celebrated and a divorce is thereafter validly obtained abroad by the alien

spouse capacitating him or her to remarry, the Filipino spouse shall likewise have capacity to remarry under

Philippine Law. The above-quoted provision was enacted to correct the unfair situation, where the status of a person

would depend on the territory where the question arises: in the Philippines, the Filipino spouse would still be legally

married and cannot re-marry; while abroad, the person who secured the divorce was no longer married to the former

and could thus remarry. However, said article does not recognize the divorce between an alien spouse and a Filipino

spouse if the divorce is obtained by the latter nor does a divorce between Filipino spouses. But the Filipino spouse

may go around the prohibition by first acquiring a foreign citizenship, as by naturalization in a foreign country, and

having done so, he/ she as a foreigner can then obtain a divorce, which will then be recognized under Article 26, if

done in good faith.

Law governing divorce

Since Article 26 of the Family Code recognizes divorce obtained by an alien spouse married to a Filipino spouse, the

question which law governs the divorce is important to determine whether the divorce obtained by the alien spouse is

valid. In the United States, the local law of the domiciliary state in which the action is brought will be applied to

determine the right to divorce. Thus, the plaintiff or petitioner must have his domicile in the state or country where the

complaint for divorce is filed by him/her.

The rationale for the above rule is based on the fact that the state of a persons domicile has the dominant interest in

the persons marital status and therefore has judicial jurisdiction to grant him a divorce. So long as the alien spouse

has acquired a domicile in the country where he/she secured the divorce, the divorce obtained therein from his/her

Filipino spouse may be regarded as valid in the country, under Section 26 of the Family Code, and will entitle the

former Filipino spouse to remarry. Philippine courts have no jurisdiction over a petition for divorce, it being outlawed

in the country. The Hague Convention Relating to Divorce and Separation of 1902 provides that the granting of

divorce or separation must comply with the national law of the spouses and the law of the place where the application

for divorce is made.103

LEGAL SEPARATION

Relative divorce or otherwise known as legal separation under the Family Code was developed by the ecclesiastical

courts at a time when, following the downfall of Rome, the supremacy of the Church was recognized and the

marriage tie regarded as indissoluble. The Siete Partidas, the governing Law here during the Spanish regime,

allowed relative divorce only. Article 55 of the Family Code provides the grounds by which the innocent spouse may

file an action for legal separation. An action for legal separation must be filed within five (5) years from the time of the

occurrence but such action shall in no case be tried before six months shall have elapsed since the filing of the

petition to give the spouse the chance to reconcile.

The laws governing absolute divorce are applicable to legal separation as provided for in the Hague Convention

Relating to Divorce and Legal Separation of 1902.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Conjugal Partnership of GainsDokument34 SeitenConjugal Partnership of GainsDemi LewkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Opinion Letter SampleDokument2 SeitenLegal Opinion Letter SampleEC Caducoy100% (2)

- Zamoranos Vs PeopleDokument2 SeitenZamoranos Vs PeopleAljay LabugaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formal Requisites of MarriageDokument9 SeitenFormal Requisites of MarriagemmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 403 MENDEZ V SHARI'A COURT DISTRICTDokument2 Seiten403 MENDEZ V SHARI'A COURT DISTRICTEmmanuel Alejandro YrreverreIiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marcelo Asuncion vs. Hon. K. Casiano P. Anunciancion AM No. MTJ-90-496Dokument2 SeitenMarcelo Asuncion vs. Hon. K. Casiano P. Anunciancion AM No. MTJ-90-496Angelo IsipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Magsumbol V People GR No. 207175 (2014) - Thief Based On Cutting of Coconut TreesDokument7 SeitenMagsumbol V People GR No. 207175 (2014) - Thief Based On Cutting of Coconut TreesDuko Alcala EnjambreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spa Format LandbankDokument3 SeitenSpa Format LandbankKaren Jing Fernando100% (1)

- Case Digests Freedom of Assembly and ReligionDokument17 SeitenCase Digests Freedom of Assembly and ReligionSweet Zel Grace PorrasNoch keine Bewertungen

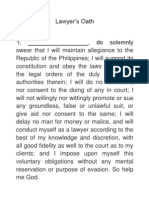

- Lawyer's OathDokument1 SeiteLawyer's OathKukoy PaktoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Requisites of MarriageDokument3 SeitenRequisites of MarriageNimpa PichayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal MemorandumDokument6 SeitenLegal MemorandumKenneth Buñag100% (1)

- XPN of Hierarchy of CourtsDokument11 SeitenXPN of Hierarchy of CourtsDanica Irish RevillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law - Legal F - Desistance - AffidavDokument9 SeitenLaw - Legal F - Desistance - AffidavNardz AndananNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAP 9 - Void ContractsDokument3 SeitenCHAP 9 - Void ContractsJongJongNoch keine Bewertungen

- ObliconDokument5 SeitenObliconGerwin AbejarNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 230784Dokument3 SeitenG.R. No. 230784Gillard Miguel GeraldeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Conjugal Partnership of GainsDokument9 SeitenThe Conjugal Partnership of GainsRyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ching Leng v. GalangDokument8 SeitenChing Leng v. GalangEarlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Example Debt Collection Letter TemplatesDokument5 SeitenExample Debt Collection Letter Templatesxzyl21100% (1)

- Quo Warranto CaseDokument27 SeitenQuo Warranto CaseBarrrMaidenNoch keine Bewertungen

- WEEK 3 - Prosecution of Civil ActionDokument8 SeitenWEEK 3 - Prosecution of Civil ActionDANICA FLORESNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABEL v. RULEG.R. No. 234457, 12 May, 2021Dokument1 SeiteABEL v. RULEG.R. No. 234457, 12 May, 2021Marlon EspinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal SeparationDokument33 SeitenLegal SeparationAngel UrbanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grande vs. Antonio Case DigestDokument2 SeitenGrande vs. Antonio Case DigestRolando SergioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exempting CircumstancesDokument198 SeitenExempting CircumstancesquasideliksNoch keine Bewertungen

- CA-G.R. CV No. 100076 Marelyn Tanedo Manalo Vs PeopleDokument9 SeitenCA-G.R. CV No. 100076 Marelyn Tanedo Manalo Vs PeopleNami Buan100% (1)

- Exemptions of Article 3 of The Civil Code of The PhilippinesDokument1 SeiteExemptions of Article 3 of The Civil Code of The Philippinessennecoronel11100% (1)

- CLAC MethodDokument1 SeiteCLAC MethodLiam LacayangaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamental Principles and PoliciesDokument115 SeitenFundamental Principles and PoliciesLeo Carlo CahanapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Memorandum SampleDokument5 SeitenLegal Memorandum SamplebelteshazzarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Opinion Sample DraftDokument3 SeitenLegal Opinion Sample DraftManuelMarasiganMismanosNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs Clemente Casta y CarolinoDokument5 SeitenPeople Vs Clemente Casta y CarolinoGyrsyl Jaisa GuerreroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oblicon Case Digests Final CompilationDokument182 SeitenOblicon Case Digests Final CompilationMae VincentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bote NotesDokument45 SeitenBote NotesSuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doctrine of Royal Prerogative of DishonestyDokument4 SeitenDoctrine of Royal Prerogative of DishonestyEstelaBenegildo100% (1)

- Inter Vivos or Mortis Causa. Succession Inter Vivos Is Ordinary Donation. Succession MortisDokument23 SeitenInter Vivos or Mortis Causa. Succession Inter Vivos Is Ordinary Donation. Succession MortisTrudgeOnNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Register of Deeds of Manila vs. China Banking Corp., 4 SCRA 1146 (1962) )Dokument7 Seiten(Register of Deeds of Manila vs. China Banking Corp., 4 SCRA 1146 (1962) )Samantha HollandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal OpinionDokument2 SeitenLegal OpinionIvoryAthenaPalarcaPosposNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hernandez Vs Court of Appeals 320 SCRA 76 08 December 1999Dokument2 SeitenHernandez Vs Court of Appeals 320 SCRA 76 08 December 1999Samuel John CahimatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sources of Legal ResearchDokument13 SeitenSources of Legal ResearchJhanelyn V. Inopia100% (2)

- Criminal Law Review NotesDokument9 SeitenCriminal Law Review NotesPaula Bianca EguiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- People of The Philippines vs. Mizpah R. ReyesDokument1 SeitePeople of The Philippines vs. Mizpah R. ReyesAnonymous 91f03cwNoch keine Bewertungen

- 132 SCRA 523 People Vs VeridianoDokument3 Seiten132 SCRA 523 People Vs VeridianoPanda Cat0% (1)

- Law Case Digests Supreme Court en Banc Decisions Philippine Constitutional LawDokument62 SeitenLaw Case Digests Supreme Court en Banc Decisions Philippine Constitutional LawBonito BulanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Writing IVDokument12 SeitenLegal Writing IVNorleviwilgemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Co-OwnershipDokument2 SeitenAffidavit of Co-Ownershipmarvilie sernaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal MaximsDokument5 SeitenLegal MaximsCharlotte GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blending of PowersDokument1 SeiteBlending of PowersTokie TokiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outline - Hierarchy of LawsDokument3 SeitenOutline - Hierarchy of LawsLoucille Abing Lacson57% (7)

- Legal Separation Separation of PropertyDokument2 SeitenLegal Separation Separation of PropertyJoshua John Espiritu100% (1)

- Title: Right To Life: The Practice of Surrogacy in The PhilippinesDokument12 SeitenTitle: Right To Life: The Practice of Surrogacy in The PhilippinesrbNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Principle of Dura Lex Sed LexDokument1 SeiteThe Principle of Dura Lex Sed LexLadyferdel Roferos0% (1)

- UntitledDokument9 SeitenUntitledJIEA THERESE SIANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflict of Laws in Marriage and DivorceDokument6 SeitenConflict of Laws in Marriage and DivorceCJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asian Comparative Law Volume 1 Pages 11 38Dokument28 SeitenAsian Comparative Law Volume 1 Pages 11 38Darwin AbesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prenuptial-Agreements-in-the-Philippines by DefinitionDokument3 SeitenPrenuptial-Agreements-in-the-Philippines by DefinitionGino GinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prenuptial Agreements in The PhilippinesDokument3 SeitenPrenuptial Agreements in The PhilippinesHusayn TamanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- COL (Marriage, Adoption, Etc)Dokument44 SeitenCOL (Marriage, Adoption, Etc)xeileen08100% (1)

- Immediate Preparation For MarriageDokument70 SeitenImmediate Preparation For MarriageJustice SalayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- San Beda College of Law: Book FiveDokument75 SeitenSan Beda College of Law: Book FiveZypress AcacioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporation Law Case DigestDokument97 SeitenCorporation Law Case DigestZypress AcacioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest Legal MedDokument142 SeitenDigest Legal MedZypress AcacioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti Money Laundering ActDokument10 SeitenAnti Money Laundering ActZypress Acacio100% (1)

- Iglesia Evangelica Metodista v. Bishop LazaroDokument4 SeitenIglesia Evangelica Metodista v. Bishop LazaroPaul Martin MarasiganNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Chapo Court Decision/ Special Administrative Measure (SAM)Dokument18 SeitenEl Chapo Court Decision/ Special Administrative Measure (SAM)Chivis MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banking Law Case CommentDokument3 SeitenBanking Law Case CommentnPrakash ShawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tankers Chartering Procedure Step by Step PDFDokument1 SeiteTankers Chartering Procedure Step by Step PDFrafaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIR V Lingayen GulfDokument3 SeitenCIR V Lingayen GulfTheodore BallesterosNoch keine Bewertungen

- RA 9267 Securitization Act of 2004Dokument11 SeitenRA 9267 Securitization Act of 2004acolumnofsmokeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Partnership DeedDokument3 SeitenProject Partnership DeedJaveria JanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitution (2) Assignment BhasviDokument25 SeitenConstitution (2) Assignment BhasviSinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Radiall Et. Al. v. GlenairDokument12 SeitenRadiall Et. Al. v. GlenairPriorSmartNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Are The Concepts of GovernanceDokument4 SeitenWhat Are The Concepts of GovernanceWennNoch keine Bewertungen

- Code of Criminal ProcedureDokument1.236 SeitenCode of Criminal ProcedureGlen C. ChadwickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taxation Law: Question No. IDokument4 SeitenTaxation Law: Question No. IOscar BladenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisprudence-II Project VIDokument18 SeitenJurisprudence-II Project VISoumya JhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oct 15 - Oct 19 NewsDokument186 SeitenOct 15 - Oct 19 NewsBig ShowNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dan Meador's InstitutionalizedDokument135 SeitenDan Meador's InstitutionalizedleshawthorneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Council of India Powers and FunctionsDokument11 SeitenBar Council of India Powers and FunctionsSonu Pandit100% (1)

- Certificates of Non Citizen NationalityDokument9 SeitenCertificates of Non Citizen NationalitySpiritually Gifted100% (2)

- PHILCONSA vs. HON. SALVADOR ENRIQUEZDokument3 SeitenPHILCONSA vs. HON. SALVADOR ENRIQUEZSwitzel SambriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Azhiya Osceola DCF ReportsDokument4 SeitenAzhiya Osceola DCF ReportsHorrible CrimeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Imbong V Hon. Ochoa, Jr. GR NO. 204819 APRIL 8, 2014 FactsDokument8 SeitenImbong V Hon. Ochoa, Jr. GR NO. 204819 APRIL 8, 2014 FactsJack NumosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cuadra V MonfortDokument2 SeitenCuadra V MonfortZoe VelascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cdi4 W7Dokument4 SeitenCdi4 W7ALBANIEL, ANDREA CLARISSE C.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Law of Crime (Indian Pinal Code) - I594 - Xid-3956263 - 1Dokument2 SeitenLaw of Crime (Indian Pinal Code) - I594 - Xid-3956263 - 1Nidhi HiranwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoening v. Seton Hall UniversityDokument15 SeitenShoening v. Seton Hall UniversityNicholas KerrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisprudence: I. Nature, Forms, KindsDokument13 SeitenJurisprudence: I. Nature, Forms, KindsGenevieve Bermudo100% (2)

- Legal Ethics Assignment-13aDokument11 SeitenLegal Ethics Assignment-13aMarianne DomingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 CIR Vs Air LiquideDokument10 Seiten1 CIR Vs Air LiquideIrene Mae GomosNoch keine Bewertungen

- w2 PDFDokument6 Seitenw2 PDFNEKRONoch keine Bewertungen

- Interview With A Certified Nut, Mercenary Leader Sydney Burnett-AlleyneDokument5 SeitenInterview With A Certified Nut, Mercenary Leader Sydney Burnett-AlleyneChris WalkerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 14 .Labor Et Al Vs NLRC and Gold City Commercial Complex, Inc., GR 110388, Sept 14, 1995Dokument10 Seiten14 .Labor Et Al Vs NLRC and Gold City Commercial Complex, Inc., GR 110388, Sept 14, 1995Perry YapNoch keine Bewertungen