Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

P ('t':'3', 'I':'2887683193') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)

Hochgeladen von

UCYSUSANTIOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

P ('t':'3', 'I':'2887683193') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)

Hochgeladen von

UCYSUSANTICopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

709

BrazJMedBiolRes41(8)2008

Exercisebybreastcancerpatients

www.bjournal.com.br

BrazilianJournalofMedicalandBiologicalResearch(2008)41:709-715

ISSN0100-879X

Effectofexerciseonthecaloricintake

ofbreastcancerpatientsundergoing

treatment

C.L.Battaglini

1

,J.P.Mihalik

1

,M.Bottaro

2

,C.Dennehy

3

,M.A.Petschauer

1

,

L.S.Hairston

1

andE.W.Shields

1

1

DepartmentofExerciseandSportScience,UniversityofNorthCarolinaatChapelHill,ChapelHill,

NC,USA

2

FaculdadedeEducaoFsica,UniversidadedeBraslia,Braslia,DF,Brasil

3

NavitasCancerRehabilitationCentersofAmerica,Inc.,Westminster,CO,USA

Correspondenceto:C.Battaglini,DepartmentofExerciseandSportScience,UniversityofNorthCarolina

atChapelHill,313WoollenGym,CampusBox8605,ChapelHill,NC27599-8605,USA

E-mail: claudio@email.unc.edu

Thepurposeofthisstudywastoexaminetheeffectsofanexerciseinterventiononthetotalcaloricintake(TCI)ofbreastcancer

patientsundergoingtreatment.Asecondarypurposewastodeterminewhetherornotarelationshipexistedbetweenchanges

inTCI,bodyfatcomposition(%BF),andfatigueduringthestudy,whichlasted6months.Twentyfemalesrecentlydiagnosedwith

breastcancer,scheduledtoundergochemotherapyorradiation,wereassignedrandomlytoanexperimental(N=10)orcontrol

group(N=10).OutcomemeasuresincludedTCI(3-dayfooddiary),%BF(skinfolds),andfatigue(revisedPiperFatigueScale).

Each exercise session was conducted as follows: initial cardiovascular activity (6-12 min), followed by stretching (5-10 min),

resistancetraining(15-30min),andacool-down(approximately8min).SignificantchangesinTCIwereobservedamonggroups

(F

1,18

=8.582;P=0.009),attreatments2and3,andattheendofthestudy[experimental(1973419),control(1488418);

experimental(1946437),control(1436429);experimental(2315455),control(1474294),respectively].Asignificant

negativecorrelationwasfound(Spearmanrho(18)=-0.759;P<0.001)betweenTCIand%BFandbetweenTCIandfatigue

levels(Spearmanrho(18)=-0.541;P=0.014)attheendofthestudy.Inconclusion,theresultsofthisstudysuggestthatan

exerciseinterventionadministeredtobreastcancerpatientsundergoingmedicaltreatmentmayassistinthemitigationofsome

treatmentsideeffects,includingdecreasedTCI,increasedfatigue,andnegativechangesinbodycomposition.

Keywords:Exercise;Breastcancer;Caloricintake;Fatigue;Bodycomposition

M.BottarowastherecipientofaproductivitygrantfromCNPq(#476206/2007-3).

ReceivedDecember13,2007.AcceptedAugust15,2008

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-

relateddeathamongwomen.Whilebreastcancerisranked

thirdamongthemostcommoncancerspresentinsociety,it

is ranked fifth among overall cancer-related deaths (1). At

present, there are approximately 10.5 million Americans

with a cancer history and 2.4 million of those are breast

cancer survivors (2). An estimated 211,240 new cases of

invasive breast cancer were diagnosed among women in

the USA in 2005 (3). Modern technology advancements,

greatereducation,significantimprovementsinadjuvantche-

motherapies,andself-examinationshavecontributedtothe

increasedsurvivalrateamongbreastcancerpatients.

Reduced capacity for work and being less able to

efficientlycompletetasks,bothofwhichareoftenaccom-

paniedbywearinessandtiredness,areconditionscharac-

teristicofcancer-relatedfatigue(4).Whiletheexactetiol-

710

BrazJMedBiolRes41(8)2008

C.L.Battaglinietal.

www.bjournal.com.br

ogy of cancer-related fatigue is not fully understood, it is

thoughttobebasedonthephysiologicalandpsychologi-

cal effects of cancer treatments. Regardless of treatment

type, the consistent and often persistent manifestation of

cancer treatment-related fatigue is pervasive.

Therehavebeenmanytheoriesconcerningthefactors

thatcontributetocancer-relatedfatigue.One,forexample,

suggests that a reduced blood count caused by chemo-

therapy could lead to anemia that results in fatigue (5,6).

Otherfactorsincludemedications,psychologicaldistress,

changes in immune function, excessive inactivity, neuro-

muscular dysfunction, and cognitive factors. The present

study, however, has focused attention on data that sug-

gestthatthebodysinabilitytoefficientlyprocessnutrients,

notable changes in the bodys nutritional requirements

duringandfollowingtreatment,andadecreaseinoverall

energy intake could be significant contributing factors to

thespecificfatigueexperiencedbycancerpatientsunder-

goingtreatment(7).Progressiveweightlossandtherateat

which weight is lost during treatment have been associ-

ated with survivorship rates (8). In addition, negative

changes in body composition have been related to poor

responses to chemotherapy and an overall decrease in

qualityoflife(8).

Exercise has been shown to have a positive physi-

ological and psychological impact on mitigating some of

the side effects associated with treatment modalities, in-

cludingpositivechangesinbodycompositionandfatigue

levels (1,7). Energy loss usually observed during treat-

menthasbeenshowntoimprovewithanaerobictraining

program (9). Results from studies that explored aerobic

and resistance training as the exercise modes showed

positiveeffectsondecreasingfatiguelevels,improvement

inqualityoflife,andmusclestrength(7,8,10,11).

Even though the majority of studies involving aerobic

and resistance exercise have reported improvements in

aerobiccapacity,musclestrength,bodycomposition,and

fatigue (12,13), the impact of exercise on caloric intake,

usually known to be altered in patients undergoing treat-

ment, has not been fully explored. Furthermore, the rela-

tionshipbetweenchangesincaloricintake,bodycomposi-

tion,andfatiguelevelshasnotbeenexploredinprevious

studiesthatinvolvedexerciseasacomplementarytherapy

aimed to assist in the mitigation of side effects of cancer

treatment. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to

examinetheeffectsofanindividualizedprescriptiveexer-

cise intervention on total caloric intake (TCI) in breast

cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation

treatment.Asecondarypurposewastodeterminewhether

ornotarelationshipexistedbetweenchangesinTCI,body

composition, and fatigue during treatment.

Material and Methods

Subjects and experimental design

Thisisarandomizedcontrolledtrialstudy[experimen-

tal (exercise) and control (no exercise)] developed and

conductedinnorthernColorado.TCIwasassessedatsix

intervals during the course of the study. Pre- (post-sur-

gery) and post-intervention (final assessment performed

attheendofthestudy)measuresofcardiovascularendur-

ance, dynamic muscular endurance, body composition

(percentbodyfat,%BF),andfatiguelevelswererecorded

andincludedinthedesign.

Twentyfemalesubjectswithagesrangingfrom35-70

yearswhohadbeenrecentlydiagnosedwithhavingbreast

cancer volunteered for this study. The following criteria

wereusedfordeterminingwhetherornotanindividualwas

includedinthestudy:a)recentbreastcancerdiagnosis;b)

designatedtoundergoanytypeofsurgery;c)requiredto

receiveeitherchemotherapyorradiation,oracombination

ofthetwoaftersurgery;d)agebetween35-70yearsduring

thecourseofthestudy.Ifcardiovasculardisease,acuteor

chronicrespiratorydisease,acuteorchronicbone,joint,or

muscularabnormalitieswereobservedduringthemedical

historyreviewandphysicalexaminationbyanoncologist,

and if it was determined that the volunteer would not be

able to engage in regular exercise, the patient was in-

formedandexcludedfromthestudy.Patientscharacteris-

ticsarepresentedinTable1.

Afterthescreeningprocessforparticipationandexpla-

nations regarding the study, the study protocol was re-

viewed and participants decided if they wished to partici-

pate in the study. The protocol and an informed consent

form approved by the University of Northern Colorados

Internal Review Board (UNCO IRB) and the North Colo-

radoMedicalCentersInternalReviewBoard(NCMCIRB)

were signed by each participant. According the Health

Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

(HIPAA), all subjects recruited after April 13, 2003 were

askedtosigntheHIPAAauthorizationtouseordisclosure

protected health information for research prior to enroll-

mentinthestudy.

Table 1. Table 1. Table 1. Table 1. Table 1. Characteristics of breast cancer patients who partici-

patedinthestudy.

Controlgroup Exercise group

Age (years) 56.6 16 57.5 23

Bodyweight(kg) 81.7 25.0 77.3 27.3

Height(cm) 169.2 10.2 168.9 10.2

Bodyfat(%) 29.84 14.9 29.13 10.1

DataarereportedasmeansSDfor10subjectsineachgroup.

711

BrazJMedBiolRes41(8)2008

Exercisebybreastcancerpatients

www.bjournal.com.br

Assessment protocols

Patientswereassignedrandomlytotwodifferentgroups

the week after diagnosis and before surgery. Before sur-

gery, the patients were assessed for TCI, fatigue levels,

bodycomposition(skinfolds)andfitness,whichwascom-

prised of cardiovascular endurance and dynamic muscu-

lar endurance tests. During the study, which lasted 6

months, TCI, body composition, and fatigue levels were

assessed 6 times throughout the investigation (pre-sur-

gery,post-surgery,attreatments1,2,3,andattheendof

the study) and 2 fitness assessments were administered

(post-surgery, and at the end of the study). During treat-

ment, the assessments were performed at regular inter-

vals at approximately 4 weeks apart according to each

patientstreatmentschedule.Becausesomepatientswere

still receiving treatment during week 21, fitness assess-

ments were administered a day other than that of the

subjectsscheduledtreatment.Ifapatientwastoreceive

onlyradiation,theirtreatmentbeganatweek5,withtheir

firstassessmentbeingadministeredatweek6,followedby

weeks10and14,andattheendofthestudyonthe21st

week. All patients were assessed at 4-week intervals

whether or not they began their treatment at week 5 as

mentioned previously.

Total caloric intake analysis

A 3-day food diary was used to record the amount of

caloric intake as determined by the recommendations of

the nutritional assessment guideline by Lee and Nieman

(14). The data were analyzed to determine whether TCI

had changed enough throughout the experiment to have

an effect on body composition. Patients were asked to

record both food and beverage consumption (including

snacks)for2daysduringtheweekand1dayduringthe

weekend.

Body composition analysis

The body composition of each patient was assessed

usingskinfoldmeasurementforthedeterminationof%BF.

Large skinfold calipers (Cambridge Scientific Industries,

Inc.,USA)wereusedforthedeterminationofbodycompo-

sition. Skinfold measurements were performed using the

3-siteskinfoldmeasurementformulaforwomen(15).For

patientswhohadundergonetransverserectusabdominis

muscle flap reconstructive surgery, triceps, thigh and

suprailiacsiteswereused.Thebodycompositionassess-

mentwasperformedapproximately30minpriortoadmin-

istrationofcancertreatmentbytheoncologist.

Self-reported fatigue analysis

FatiguelevelswereassessedusingtherevisedPiper

etal.(16)FatigueScale(PFS).This22-itemself-reported

scalemeasuresfatigueonascaleof0to10,aswellas4

subjective fatigue domains: affective, sensory, cognitive,

andbehavioral,yieldingatotalfatiguescore.Themajority

ofcancerpatientsexperiencethehighestlevelsoffatigue

approximately 3 days following treatment. Patients were,

therefore, asked to answer questions on the PFS during

the last day of the week before they reported to the next

scheduled assessment/treatment.

Fitness assessment

Theassessmentofcardiovascularenduranceanddy-

namic muscular endurance were included in the fitness

assessments. Heart rate responses were determined by

each patient wearing a heart rate monitor throughout the

cardiovascular assessments and the control of intensity

duringexercisesessions.Fitnessassessmentswereper-

formedattheRockyMountainCancerRehabilitationInsti-

tuteattheUniversityofNorthernColorado(Greeley,CO,

USA). Cardiovascular endurance assessments were per-

formedonaQuintonmodel65treadmill(USA).Cardiovas-

cular endurance (VO

2max

) was assessed using the modi-

fiedBrucetreadmillprotocol.Thetest,whichisasubmaxi-

mal exercise test, is often used for high-risk populations

because of the low level of stress it imposes on patients

(17).

The following exercises were utilized to assess the

dynamic muscular endurance of each subject: leg exten-

sion, seated leg curl, lateral pull down, and seated chest

press. The assessments were performed on LifeFitness

(USA)andQuantum(USA)weightmachines.Asubmaxi-

malenduranceprotocolthatrequiredtheuseoffreeweights

helped predict one maximal repetition for each subject.

This submaximal endurance protocol was developed for

middle-agedandolderwomen(18).

Exercise intervention

Theexerciseinterventionassignedtotheexperimental

group began in week 6 of the study and lasted until the

conclusion of the study following week 21. The exercise

group began their routine approximately 3 weeks prior to

receivingtheirfirstcancertreatmentduetothepost-can-

cer surgery treatment schedule. Exercise sessions were

heldattheRockyMountainCancerRehabilitationInstitute

and/or at the University of Northern Colorado Campus

Recreation Center at no cost to the patient. Patients as-

signedtotheexperimentalgroupexercised2daysaweek

fornolongerthana60-minperiod.Theresttimeallowed

betweeneachsessionwasnolessthan48handnomore

than 84 h. Each patient was assigned an individualized

exercise intervention program designed in accordance

712

BrazJMedBiolRes41(8)2008

C.L.Battaglinietal.

www.bjournal.com.br

gested that while controlling energy intake, it may be

possibletoincreaseenergyexpenditurethroughexercise

(21).Eachexercisesessionwasmodifiedaccordingtothe

patients physical state prior to the exercise session. On

the days in which patients were experiencing extreme

fatigue the exercise session intensity and duration were

modified.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the statistical software

programSPSS,version14.0,forWindows.Statisticalsig-

nificancewasdeterminedwithaprobabilityvaluelessthan

or equal to 0.05. For the assessment of changes and

differencesinTCIbetweentheexerciseandcontrolgroups,

a 2 x 6 mixed model repeated measures ANOVA was

used. TCI measurements used for the analyses included

measurements obtained prior to surgery, post-surgery,

duringtreatments1,2,3,andattheendofthestudy(final

assessment). Tukey HSD post hoc analyses were per-

formedtodetermineatwhichtimeduringtreatmentsignifi-

cant differences between groups were observed. For the

correlationanalysesrelatingTCI,%BF,andfatiguelevels

inboththeexerciseandcontrolgroupsduringthestudy,a

Spearman rho correlation was employed. The variables

includedinthemodelwerethechangescoreforTCIand

for%BF,andfatiguelevels.ThechangeinTCI,%BF,and

fatigue were determined as the difference between the

results of the final assessment compared to the initial

assessment.

Results

Asignificanttimeversusgroupinteractionwaspresent

(F

4.346,78.221

=7.895;P<0.001).Inaddition,themaineffect

forgroupwassignificant(F

1,18

=8.582;P=0.009)indicat-

ingthattheexercisegroup(TCI=1998.531451.65kcal)

had a significantly higher TCI than our patients in the

control group (TCI = 1597.782 359.08 kcal) (Figure 1).

Theeffectfortimewasmarginallysignificant(F

4.346,78.221

=

2.084;P=0.085).

After combining the exercise and control groups into

one, a relationship between TCI and %BF was explored.

A negative correlation was found (rho(18) = -0.759; P <

0.001),indicatingasignificantlinearrelationshipbetween

the two variables. Patients with a greater change in TCI

(higherduringfinalassessmentcomparedtopre-surgery)

tendedtohavelowerchangesin%BF.

Using the same procedure, the relationship between

the change in TCI and fatigue level (PFS) was also ana-

lyzedusingaSpearmanrhocorrelation.Anegativecorre-

lationwasfound(rho(18)=-0.541;P=0.014),indicatinga

with the recommendations of the American College of

Sports Medicine exercise guidelines for elderly popula-

tions(19)andguidelinespublishedinExerciseandCancer

Recovery (20). Intensities varying from 40-60% of the

patients predicted maximum exercise capacity were as-

signedtoeachactivityandwerebasedontheresultsofthe

firstfitnessassessmentadministeredpriortosurgery.

Each exercise session was supervised by an under-

graduate or graduate cancer exercise specialist from the

Department of Sport and Exercise Science, University of

NorthernColorado.Theexercisetrainingincludedcardio-

vascular,resistance,andflexibilitytraining.Eachexercise

session was conducted as follows: initial cardiovascular

activity(6-12min),followedbyastretchingsession(5-10

min),resistancetraining(15-30min),andacool-downthat

included stretching activities (approximately 8 min).

Theintensitiesusedfortheresistancetrainingprogram

weredeterminedbythefirstfitnessassessment(18).The

protocolwasusedtopredictthehighestlevelofintensity

for one maximum repetition during a sub-maximal endur-

ancetestformiddle-toolder-agedwomen.Allmajormuscle

groups were utilized during the resistance training ses-

sions.TheexerciseswereperformedusingtheLifeFitness

andQuantumweightmachines,freeweights,elasticbands,

or therapeutic balls. The resistance exercises were as

follows: lateral and front raises, triceps extension, leg

press,legextension,legcurl,standingcalfraises,horizon-

tal chest press, lateral pull down, alternating bicep curls

with dumbbells, regular crunches, oblique crunches, and

lower abdominal crunches.

Patientsassignedtotheexercisegroupincreasedthe

number of sets performed each week, which never ex-

ceededthreesetsofeachexercise.Duringthefirstweek,

subjectsassignedtotheexperimentalgrouphadtoendure

onesetforeachexerciseperformedduringthesessions.

Subjects assigned to the exercise group progressively

increasedtotwothenthreesetsperexercisebytheendof

the study. Movements during each exercise were per-

formedatmoderatespeed(3sofconcentricphaseand3

s of the eccentric phase of the movement during each

repetitionforeachexercise).Resttimebetweeneachset

and each exercise varied according to the subjects de-

sires,butwasapproximately1min.

Cardiovascular activities included the following: walk-

ing on a treadmill [Precor C966 (USA), Quinton 65, or

LifeFitness TR 9500 HR, the use of the cycle ergometer

(LifeFitness 8500 HR, or elliptical equipment LifeFitness

CT 9500 HR or Precor EFX 546). Exercise training pro-

gramshavebeenshowntoimprovetheoverallqualityof

life, level of fitness, improved levels of self-esteem, and

confidence of cancer patients (9). It has also been sug-

713

BrazJMedBiolRes41(8)2008

Exercisebybreastcancerpatients

www.bjournal.com.br

significantrelationshipbetweenTCIandfatigue.Patients

with a greater change in TCI tended to have greater

changes in fatigue level (fatigue level was lower during

finalassessmentthanatpre-surgery).

Discussion

Thisstudywasdesignedtoexaminetheimpactofexer-

cise on TCI in breast cancer patients undergoing chemo-

therapy or radiation treatment. The results of the current

study suggest that an individualized prescriptive exercise

programincludingaerobic,flexibility,andresistancetraining

helps to increase breast cancer patients overall TCI while

receiving treatment. Patients placed in the exercise group

experienced an increase in TCI of 20% while the control

group experienced a decrease of approximately 7%. The

significant increase of TCI demonstrated by the exercise

group could be due to the impact of exercise on fatigue,

nausea,andthebodysphysiologicalneedfornourishment

followingparticipationinphysicalactivity.

The increased caloric intake experienced by the exer-

cise group may have contributed to the elevated energy

levelsreportedbypatientsinthisgroupandthusreducing

the feeling of fatigue experienced prior to engaging in the

exerciseregimen.Anotherfindingofgreatimportancewas

the relationships observed between TCI and %BF. The

resultsofthecurrentstudyaresomewhatinagreementwith

astudyconductedbyWinninghamandMacVicar(22).They

examinedtheimpactonnauseaofa10-weekaerobicexer-

ciseprogramadministeredthreetimesperweek.Thepopu-

lation included in the study was breast cancer patients

undergoing chemotherapy. A group of patients were ran-

domizedtoeitheranexercise(aerobictraining),aplacebo

(lightflexibilityworkouts)ortoacontrolnon-exercisegroup.

Significant improvements were observed in the exercise

groupbutnotintheplaceboorcontrolgroups.Theseinves-

tigatorsconcludedthattheimpactofaerobicexercisedid,in

fact,reducenauseaintheaerobicexercisegroupandthat

aerobic training could be safely implemented during treat-

ment.Sincenauseaisacommonsymptomexperiencedby

cancer patients during treatment, Winningham and Mac-

Vicarsstudyshowedthatthistypeofexercisecanreduce

symptoms of nausea during treatment. Even though the

currentstudydidnotassessnauseaduringtreatment,itis

believedthattheimpactoftheexerciseinterventionusedin

the current study may have impacted nausea and conse-

quentlyallowedpatientsintheexercisegrouptoexperience

ahighercaloricintakecomparedtothecontrolgroup.

Oneofthemajorissuesinthebreastcancerpopulation

is the increase in body weight during treatment. This in-

creaseinbodyweightisusuallyfollowedbyincreased%BF

and reduced lean body mass. The increase in adiposity is

significantlyassociatedwithdecreasesurvivalandre-occur-

rencerates(23).Furthermore,inalargecohortstudy,Tretli

et al. (24) found that the association between obesity and

poorbreastcanceroutcomewasofextremeimportance.In

thatstudy,womendiagnosedwithstageIbreastcancerwho

were in the upper quintile of body mass index were 70%

morelikelytodyefrombreastcancerthanthosebelowthis

level. Even though an increase in body weight usually oc-

cursduringpalliativecare,duringtreatment,decreasedTCI

caninducelossofleantissuewithincreasesin%BFthatcan

decrease overall functionality, tremendously affecting the

abilityofpatientstoperformeventhesimpledailytasks.The

present study is the first that has explored the impact of

exerciseontherelationshipbetweenTCIandbodycompo-

sitioninbreastcancerpatientsundergoingtreatment.

Thesecondpurposeofthisstudywastodeterminethe

extent of the relationship between TCI, body composition,

andfatiguethroughouttreatment.Ourfindingsindicatedthat

breastcancerpatientsundergoingtreatmentwhoengagein

physicalactivityexperienceahighercaloricintakethrough-

outthedurationoftreatmentthanthosewhoengageinlittle

to no physical activity while decreasing %BF and fatigue

levels compared to patients who do not engage in regular

physical activity. Galvao and Newton (1) reviewed many

studiesthatusedexerciseasaninterventiontomitigateside

effects of cancer treatment and they found quite a few

studiesinwhichbodycompositionofpatientsinanexercise

groupeithermaintainedbodyweightandbodycomposition

orimprovedbodycompositionsignificantly.

Winninghametal.(25)conductedastudytodetermine

theeffectsofaerobictrainingonbodycompositioninbreast

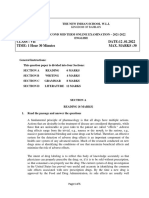

Figure 1. Figure 1. Figure 1. Figure 1. Figure 1. Effect of exercise on total caloric intake of breast

cancer patients under treatment. The figure describes a period

of24weeks.*P0.05comparedtocontrolgroup(2x6mixed

model repeated measures ANOVA).

714

BrazJMedBiolRes41(8)2008

C.L.Battaglinietal.

www.bjournal.com.br

cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Patients were

assignedtoanexercisegroupthatperformedaerobictrain-

ing for 10-12 weeks. The subjects exercised at a 60-80%

intensityofmaximalheartrate.Usingtheskinfoldmeasure-

ment, they reported increased lean body mass and de-

creasedfattissueforthesubjectswhoexercised.Similarly,

thepresentstudyfoundimprovementinbodycomposition.

ThemajordifferencewiththeWinninghamstudywasthatan

exerciseinterventioncomposedofaerobic,resistancetrain-

ing,andflexibilitywasusedinthecurrentstudy.

Studies examining the impact of exercise on fatigue

levels of breast cancer patients have also shown great

improvement compared to baseline results or control

groups. In three studies conducted by Schwartz and col-

leagues (26-28), breast cancer patients engaged in 4

weeksofaerobictrainingconsistingofwalkingshoweda

significant decrease in overall fatigue levels. Mock et al.

(29)usingasimilarbutlongerdurationprotocol(5-6weeks)

also found significant reduction of fatigue levels. A study

conductedbySegaletal.(30)usingaprotocolconsisting

ofresistancetrainingastheprimaryformofexerciseanda

prostate cancer population also found a significant de-

creaseinoverallfatiguelevels.Thecurrentstudyuseda

combinationofaerobic,resistance,andflexibilityworkouts

as the intervention. In agreement with the studies cited

above, a significant reduction in fatigue levels was also

observedintheexercisegroupbutnotinthecontrolgroup.

Besidesconfirmingsimilarresultsdescribedinthelitera-

ture, the present study also detected a significant relation-

ship between both %BF and fatigue levels and TCI. The

improvement in body composition and the relationship be-

tween%BFandTCIwasagreatsurprise.Althoughoverall

bodyweightwasmaintainedintheexercisegroupthrough-

outtheexperiment,theresultingdecreasein%BFindicated

the significance of exercise intervention in promoting lean

body mass. This correlation suggests that exercise pro-

gramsperformedinconjunctionwithcancerpatientsunder-

going treatment in this study were sufficient to cause a

positive change in body composition regardless of the in-

creaseinTCI.Breastcancerpatientsundergoingtreatment

areknowntoeithergainorloseweight,sometimesresulting

in obesity or cancer-mediated cachexia. The reduction in

%BFwhilemaintainingbodyweightobservedasaresultof

the exercise program administered throughout the current

study are positive indicators of the impact of exercise on

cancer patients while receiving treatment and should be

further explored. If the results of the current study can be

reproducedinalargertrial,exercisemayturnintoapowerful

intervention to assist patients to maintain or improve their

body weight/body composition, creating opportunities for

bettertreatmentoutcomesandimprovementinsurvival.

Fatigue experienced by cancer patients has been de-

scribedasaprocessinwhichbothpsychologicalandphysi-

ologicalchangesduringandaftertheadministrationofcan-

cer treatments lead patients to experience a decrease in

theiroverallfunctionality(9).Therewasasignificantinverse

relationshipobservedinthecurrentstudydemonstratingan

increase in TCI paired with a reduction in fatigue levels in

patientsassignedtotheexercisegroup.Thedevelopmentof

fatigueinbreastcancerpatientsisbelievedtobecausedby

numerousfactors.Theresultsofthecurrentstudy,however,

suggestthatTCIbecomesanimportantfactorinmanaging

fatigue levels throughout treatment and therefore further

investigations on caloric intake during treatment for breast

cancerpatientsshouldbeexplored.

Sinceweightchangesareusuallyassociatedwithpoor

diagnosis and treatment outcomes with adverse effects

beingassociatedwiththeriskforthedevelopmentofcardio-

vasculardiseaseanddiabetes,andforbreastcancerrecur-

rence,andtoincreasechancesforlong-termsurvival,exer-

ciseseemstobeapowerfulandsafeinterventionforbreast

cancerpatients.Breastcancersurvivorsshouldbeadvised

to engage in healthy lifestyles to maintain healthy weight.

Even if body weight cannot be maintained to a recom-

mended level, research has shown that as little as 5-10%

reduction in a period of 6-12 months is sufficient to elicit

positive physiological changes, i.e., changes in elevated

plasmalipidsandhighfastinglevelsofinsulin(31).Breast

cancerpatientsshouldbeencouragedtomaintainoreven

increasetheirbodyweightduringtreatment.Aftertreatment,

themaintenanceofweightorsafeweightreductionthrough

exercise and healthy diet should be encouraged for those

breast cancer survivors who gained more weight than ex-

pected.Moderateexercise,duringandaftertreatmentshould

be considered for the maintenance of lean muscle mass

whileavoidingexcessbodyfat(32).

Theresultsofthisstudysuggestthattheadministration

ofexerciseastreatmentinbreastcancerpatientsreceiving

chemotherapymayassistinthemanagementofsomeside

effects, including a decrease in TCI, increased fatigue lev-

els,andnegativechangesinbodycomposition.Therefore,it

isrecommendedthatanindividualizedexerciseprescription

composed of aerobic, resistance, and flexibility training be

suggestedasaformofadjuncttherapytocancertreatment

toimproveTCI,decreasefatiguelevels,whilealsoimpacting

positively changes in body composition and fatigue levels

amongbreastcancerpatientsundergoingtreatment.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the women who partici-

patedinthestudy.

715

BrazJMedBiolRes41(8)2008

Exercisebybreastcancerpatients

www.bjournal.com.br

References

1. Galvao DA, Newton RU. Review of exercise intervention

studiesincancerpatients.JClinOncol2005;23:899-909.

2. NationalCancerInstitute(NCI).Dictionaryofcancerterms.

ht t p: / / www. cancer . gov/ t empl at es/ db_al pha. aspx?

expand=B.

3. American Cancer Society (ACS). Breast cancer facts and

figures 2005-2006. http:www.cancer.org.

4. StasiR,AbrianiL,BeccagliaP,TerzoliE,AmadoriS.Can-

cer-related fatigue: evolving concepts in evaluation and

treatment. Cancer2003;98:1786-1801.

5. AndrewsP,MorrowG,HickokJ,RoscoeJ,StoneP.Mech-

anismsandmodelsoffatigueassociatedwithcancerandits

treatment:evidencefrompreclinicalandclinicalstudies.In:

Armes J, Krishnasamy M, Higginson I (Editors), Fatigue in

cancer.NewYork:OxfordPress;2004.p51-87.

6. CarteniG,GiannettaL,UcciG,DeSignoribusG,Vecchione

A,PinottiG,etal.Correlationbetweenvariationinqualityof

life and change in hemoglobin level after treatment with

epoetin alfa 40,000 IU administered once-weekly. Support

CareCancer2007;15:1057-1066.

7. BattagliniC,BottaroM,DennehyC,RaeL,ShieldsE,Kirk

D, et al. The effects of an individualized exercise interven-

tiononbodycompositioninbreastcancerpatientsundergo-

ingtreatment.SoPauloMedJ2007;125:22-28.

8. Tisdale MJ. Wasting in cancer. J Nutr 1999; 129: 243S-

246S.

9. DimeoF,RumbergerBG,KeulJ.Aerobicexerciseasthera-

pyforcancerfatigue.MedSciSportsExerc1998;30:475-

478.

10. Daley AJ, Crank H, Saxton JM, Mutrie N, Coleman R,

Roalfe A. Randomized trial of exercise therapy in women

treatedforbreastcancer.JClinOncol2007;25:1713-1721.

11. Headley JA, Ownby KK, John LD. The effect of seated

exercise on fatigue and quality of life in women with ad-

vanced breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004; 31: 977-

983.

12. Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, Gelmon K, Reid RD,

Friedenreich CM, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance

exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant che-

motherapy:amulticenterrandomizedcontrolledtrial.JClin

Oncol2007;25:4396-4404.

13. SegalR,EvansW,JohnsonD,SmithJ,CollettaS,Gayton

J,etal.Structuredexerciseimprovesphysicalfunctioningin

women with stages I and II breast cancer: results of a

randomizedcontrolledtrial.JClinOncol2001;19:657-665.

14. Lee R, Nieman D. Nutritional assessment. New York:

McGrawHill;2003.

15. Jackson AS, Pollock ML, Ward A. Generalized equations

forpredictingbodydensityofwomen.MedSciSportsExerc

1980;12:175-181.

16. Piper BF, Dibble SL, Dodd MJ, Weiss MC, Slaughter RE,

Paul SM. The revised Piper Fatigue Scale: psychometric

evaluationinwomenwithbreastcancer.OncolNursForum

1998;25:677-684.

17. Heyward V. Advanced fitness assessment and exercise

prescription.Champaign:HumanKinetics;1998.

18. Kuramoto K, Payne V. Predicting muscular strength in

women: a preliminary study. Res Q Exerc Sport 1995; 66:

168-172.

19. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSMs guidelines

forexercisetestingandprescription.Baltimore:Williams&

Wilkins;2000.

20. Schneider C, Dennehy C, Carter S. Exercise and cancer

recovery.Champaign:HumanKinetics;2003.

21. ThompsonHJ,ZhuZ,JiangW.Dietaryenergyrestrictionin

breastcancerprevention.JMammaryGlandBiolNeoplasia

2003;8:133-142.

22. WinninghamML,MacVicarMG.Theeffectofaerobicexer-

ciseonpatientreportsofnausea.OncolNursForum1988;

15: 447-450.

23. RockCL,Demark-WahnefriedW.Nutritionandsurvivalaf-

terthediagnosisofbreastcancer:areviewoftheevidence.

JClinOncol2002;20:3302-3316.

24. Tretli S, Haldorsen T, Ottestad L. The effect of pre-morbid

heightandweightonthesurvivalofbreastcancerpatients.

BrJCancer1990;62:299-303.

25. Winningham ML, MacVicar MG, Bondoc M, Anderson JI,

Minton JP. Effect of aerobic exercise on body weight and

compositioninpatientswithbreastcanceronadjuvantche-

motherapy.OncolNursForum1989;16:683-689.

26. Schwartz AL. Fatigue mediates the effects of exercise on

qualityoflife.QualLifeRes1999;8:529-538.

27. SchwartzAL.Dailyfatiguepatternsandeffectofexercisein

womenwithbreastcancer.CancerPract2000;8:16-24.

28. Schwartz AL, Mori M, Gao R, Nail LM, King ME. Exercise

reducesdailyfatigueinwomenwithbreastcancerreceiving

chemotherapy.MedSciSportsExerc2001;33:718-723.

29. Mock V, Pickett M, Ropka ME, Muscari LE, Stewart KJ,

Rhodes VA, et al. Fatigue and quality of life outcomes of

exercise during cancer treatment. Cancer Pract 2001; 9:

119-127.

30. Segal RJ, Reid RD, Courneya KS, Malone SC, Parliament

MB, Scott CG, et al. Resistance exercise in men receiving

androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin

Oncol2003;21:1653-1659.

31. Anonymous.USDAdietaryguidelinesforAmericans.Rock-

ville:USDepartmentofHealthandHumanServices.Home

andGardenBulletinNo.232:239;2000.

32. Brown JK, Byers T, Doyle C, Coumeya KS, Demark-

WahnefriedW,KushiLH,etal.Nutritionandphysicalactiv-

ity during and after cancer treatment: an American Cancer

Societyguideforinformedchoices.CACancerJClin2003;

53: 268-291.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- (SINOVAC) Informed Consent Form - Eng March 5 2021Dokument1 Seite(SINOVAC) Informed Consent Form - Eng March 5 2021Mark Anthony RosasNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21 Susar Rev2 2006 04 11Dokument26 Seiten21 Susar Rev2 2006 04 11chris2272Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care Plan Level IIIDokument8 SeitenNursing Care Plan Level IIINneka Adaeze AnyanwuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Audit Manual Clinical TrialDokument22 SeitenAudit Manual Clinical TrialnikjadhavNoch keine Bewertungen

- GoutDokument75 SeitenGoutVan Talawec100% (2)

- Guideline For Drug Information CenterDokument25 SeitenGuideline For Drug Information Centerorang negra100% (1)

- Drug Therapy Assessment Worksheet (Dtaw)Dokument5 SeitenDrug Therapy Assessment Worksheet (Dtaw)Mica Charish VillaluzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Random Drug StudyDokument94 SeitenRandom Drug Studykonzen456Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore, KarnatakaDokument19 SeitenRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore, KarnatakaARJUN BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vii Eng Second Mid Term Online Exam QuestionDokument5 SeitenVii Eng Second Mid Term Online Exam QuestionAsghar AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Side Effects of Pregabalin DrugDokument20 SeitenSide Effects of Pregabalin DrugtulipcatcherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient-Safe Communication StrategiesDokument7 SeitenPatient-Safe Communication StrategiesSev KuzmenkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corticosteroids For Bacterial Keratitis - The Steroids For Corneal Ulcers Trial (SCUT)Dokument8 SeitenCorticosteroids For Bacterial Keratitis - The Steroids For Corneal Ulcers Trial (SCUT)Bela Bagus SetiawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- AAPCDokument10 SeitenAAPCprincyphilip67% (3)

- 10 Herbal MedicinesDokument30 Seiten10 Herbal MedicinesMaria Lyn ArandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MakalahDokument585 SeitenMakalahaulia maizoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kasus AsmaDokument5 SeitenKasus AsmaHananun Zharfa0% (3)

- User Manual: Restoring Life's Vitality!Dokument52 SeitenUser Manual: Restoring Life's Vitality!LuisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical ErrorDokument75 SeitenMedical ErrorVanessa Sugar Syjongtian SiquianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benefit of Onion As Traditional MedicineDokument26 SeitenBenefit of Onion As Traditional MedicineFazriatu AuliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines On Counseling: Approved by PEIPBDokument7 SeitenGuidelines On Counseling: Approved by PEIPBEric Chye TeckNoch keine Bewertungen

- DextroseDokument1 SeiteDextroseAdrianne BazoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Discovery and Drug DevelopmentDokument20 SeitenDrug Discovery and Drug DevelopmentsilviaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 5 Drugs Acting On The Immune SystemDokument30 SeitenUnit 5 Drugs Acting On The Immune SystemBea Bianca Cruz100% (1)

- Should The Government Regulate Prescription Drugs in TV AdsDokument12 SeitenShould The Government Regulate Prescription Drugs in TV Adsknown789524Noch keine Bewertungen

- RMO Orientation AIRMEDDokument130 SeitenRMO Orientation AIRMEDqueenartemisNoch keine Bewertungen

- EAROL InstruccionesDokument2 SeitenEAROL InstruccionesHector MercadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 1Dokument15 SeitenUnit 1kunalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The New Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling RuleDokument3 SeitenThe New Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling RuleVijendra RNoch keine Bewertungen

- Montelukast SodiumDokument2 SeitenMontelukast Sodiumapi-3797941100% (2)