Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Untitled

Hochgeladen von

api-2652371800 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

24 Ansichten4 SeitenDeveloping innovative leaders through undergraduate medical education. Lead for TEMPUS project on Modernising Medical Education in Eastern European Neighbouring Areas. Requires demonstration of effective leadership skills to deal with the increasing complexity of working effectively in the NHS.

Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenDeveloping innovative leaders through undergraduate medical education. Lead for TEMPUS project on Modernising Medical Education in Eastern European Neighbouring Areas. Requires demonstration of effective leadership skills to deal with the increasing complexity of working effectively in the NHS.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

24 Ansichten4 SeitenUntitled

Hochgeladen von

api-265237180Developing innovative leaders through undergraduate medical education. Lead for TEMPUS project on Modernising Medical Education in Eastern European Neighbouring Areas. Requires demonstration of effective leadership skills to deal with the increasing complexity of working effectively in the NHS.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 4

2013 Radcliffe Publishing Limited Teaching exchange 61

Developing innovative leaders

through undergraduate medical

education

Anne-Marie Reid EdD BDS MEd Cert Ed FHEA

Senior Lecturer, School of Medicine, University

of Leeds. Lead for TEMPUS project on

Modernising Medical Education in Eastern

European Neighbouring Areas (MUMEENA)

Keywords: leadership skills, team work,

undergraduate curriculum

INTRODUCTION

The requirements of Tomorrows Doctors

1

to be

Practitioners, Professionals and Partners includes

the demonstration of effective leadership skills to

deal with the increasing complexity of working

effectively in the NHS. This is in response to the

Darzi Next Stage Review

2

which sets out clearly

the links between leadership, organisational

performance and patient outcomes. In addition to

a focus on outcomes for medical graduates, policy

drivers and guidance in Good Medical Practice,

3

Leadership and Management for all Doctors

4

and

the NHS Framework for Leadership

5

have echoed

the need for development of effective teamworking

and leadership. In primary care, practice-

based commissioning and the move to clinical

commissioning groups (driven by the NHS and Social

Care Act, 2012)

6

requires practitioners to develop

greater understanding of, and expertise in, a range

of leadership and management skills. This includes

managing resources, both human and financial,

understanding leadership in multiprofessional teams

and developing negotiation skills in a more business-

orientated environment. Irrespective of the extent to

which primary care practitioners feel enthusiastic

about these requirements on either a personal or

political level, it is incumbent upon medical schools

to prepare undergraduates to face these demands,

rather than assuming that there will be plenty of

time following graduation. This early preparation

needs to support undergraduates in developing

an understanding of the demands of leadership

within a current practice context, but also needs to

encourage them to become the innovative leaders

of tomorrow, who not only respond to policy and

practice demands, but actively contribute to policy

making and empowering others, not least, patients.

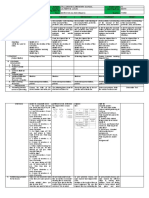

THE LEADERSHIP CURRICULUM

Mindful of these changing demands, and as part

of a curriculum review which began in 2008, the

School of Medicine in Leeds has developed a new

Innovation, Development, Enterprise And Leadership

& Safety (IDEALS) curriculum strand which spirals

through the five years of the MBChB programme. A

core working group was established to develop the

IDEALS strand, which incorporates six key themes:

Leadership and management

Professionalism

NHS Business Understanding the Service

Patient safety

Learning and teaching skills

Personal and professional development (including

careers).

Having agreed the main themes, smaller subgroups

of the core group were formed to develop these

individually, with the larger working group being

convened on a regular basis to ensure synergy

between the themes. The starting point for

elaboration of the teaching on leadership and

management was in developing a curriculum to meet

the outcomes set by Tomorrows Doctors

1

(Box 1).

Box 1 Outcomes set by Tommorrows Doctors

Outcome 15 Communicate effectively with

patients and colleagues in a medical context

(h) Communicate effectively in various

roles, for example, as patient advocate,

teacher, manager or improvement leader.

Outcome 22 Learn and work effectively within

a multi-professional team

(a) Understand and respect the roles and

expertise of health and social care

professionals in the context of working

and learning as a multi-professional

team.

(d) Demonstrate ability to build team capacity

and positive working relationships and

undertake various team roles.

Tomorrows Doctors (GMC 2009)

THE SPIRAL CURRICULUM: THE

EARLY YEARS

The IDEALS curriculum is structured in accordance

with the nature of a spiral curriculum

7

where

students are iteratively exposed to increasingly

complex concepts and structures which require

higher-level skills and application in response

to them. The early teaching is concentrated on

exploring the differences between groups and

teams and developing understanding of effective

teamworking through engaging with problem-solving

tasks. Students normally work in small groups and

then each group provides feedback on both the task

itself and the contribution made by individuals to the

62 Teaching exchange

team. The discussion is placed within the context

of theoretical models of teamwork, with students

being encouraged to critique the evidence base to

support teamwork theory (or generally the lack of a

sound evidence base!) and the generalisability of the

models. All students come with some experience of

teamworking, so that they can appreciate that the

ideal formula for a sports team, for example, may

not resemble that of a team in a critical care unit.

Although models of teamworking and role theory are

widely used in business and increasingly in health

care, there is little research evidence to support their

value when applied in different contexts. Discussion

of this helps students to develop critical thinking skills

which are essential in effective leadership. Towards

the end of year 1 the emphasis moves towards

working in interprofessional and multiprofessional

teams with consideration of professional roles and

appropriate leadership responsibility according

to patient need and healthcare setting. Students

take part in a day of interprofessional learning with

nursing and healthcare students which is focused

on patient safety, a topic particularly appropriate for

interprofessional learning groups.

The next phase of the curriculum debates

leadership and management as contested concepts,

terms often used interchangeably, and subject to

different understandings through time and history.

Key lectures provide an overview of the theoretical

framework which outlines the move away from trait

theories

8

of leadership which have an emphasis on the

powerful charismatic personality of the individual, to

the concept of contingency leadership

9

where there

is recognition of a more dynamic relationship between

the leader, followers and the context. Working on

small group tasks allows students to explore the

differences between leadership and management,

and the value of different approaches to leadership

within the policy and practice context of the NHS. The

policy context is outlined and debated in the theme

of Understanding the Business of the NHS which is

delivered alongside the leadership and management

curriculum. This supports an appreciation that

effective leaders also need to have an understanding

of management principles and practices, particularly

in the area of primary care.

10

Early exposure to clinical placements offers the

opportunity for reflection on practice experience

to reinforce the concepts and understanding of

leadership. This is enabled by dedicating one half

day per week to placements in Year 1, and one day

per week in Year 2, with time spent in both primary

and secondary care. Students are attached to the

same GP practice over this period which allows them

to form good relationships with the practice team

and to observe teamwork and leadership in action.

THE SPIRAL CURRICULUM: THE

LATER YEARS

In the later years, contemporary theories of

leadership which emphasise the links between

leadership and emotional intelligence

11

are explored,

with an emphasis on developing understanding

of the quality of the relationship between the

leader, individuals and the team as a whole. An

emphasis is placed on empowering others through

an appreciation of distributed leadership and

recognising the role of non-medical staff members

as team leaders where appropriate. A focus on the

links between leadership, teamworking and patient

safety allows exploration of real practice scenarios

where patient safety has been compromised. This

leads naturally to an appreciation of the negative

impact of hierarchies on effective communication,

and the relationship between organisational culture,

team culture and communication.

The process of change management is introduced

through a presentation on the Kotter model

10

and

groupwork tasks, where students apply the model

to specific case scenarios involving changes in

healthcare practices. This is linked to the current

policy context, with consideration of the barriers

to change, and the ways in which the outcomes of

change are often far from those intended. This leads

on to the concept of transformational leadership

8

and the need for transformational leaders in both

primary and secondary care who can support others

in embracing change and direct this in the interest

of patients. Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-Metcalfe

12

describe a transformational leader as someone

who encourages and enables the development of an

organisation that is characterised by a culture based

on integrity, openness and transparency (p. 4).

Their extensive research on leadership in complex

health and social care environments concludes that

transformational leadership has a notable positive

impact on staff motivation, commitment and

organisational effectiveness. This evidence base, in

support of a transformational model of leadership

which takes account of contextual factors, is

contrasted with the current emphasis on leadership

competencies encompassed within the NHS

Leadership framework, which has been critiqued as

being rather mechanistic, behaviourally focused and

tending to fragment the leadership role.

13

THE TEACHING TEAM AND

APPROACH TO LEARNING

A clinical academic with a background in managing

palliative care services leads the IDEALS strand,

with a core team of clinical academics who have

responsibility for each of the themes. The core group

is supported by a team of facilitators with a range

of backgrounds in health and social care including

GPs, dental practitioners, nurses, a pharmacist,

a physiotherapist, a paramedic, a retired chief

executive of an NHS Trust, a community worker and

a management consultant. The commitment to an

understanding of leadership within the context of

interprofessional and multiprofessional teamworking

is modelled through utilising the experience and

Teaching exchange 63

expertise of this range of staff to develop and deliver

the curriculum. Each facilitator teaches the same

group of approximately 12 students for one half day

each week throughout year 1 and year 2 with less

concentrated campus-based teaching in later years.

Regular training days are held for the whole team to

enable new materials to be discussed and different

perspectives to be considered, a process which

enriches the curriculum. Students greatly appreciate

the knowledge of current developments and the

wide range of expertise brought by this diverse and

experienced team.

I initially develop the teaching materials as I have

responsibility for the leadership and management

theme. The materials are reviewed with the

teaching team and amendments made before and

after teaching in the light of feedback from both

facilitators and students. Learning and teaching

methods include a few lecture presentations which

are supported by audiovisual material and further

reading on the virtual learning environment (VLE).

Most teaching is centred on groupwork tasks using

case scenarios, storytelling through digital media

and short videos and podcasts. Video clips and

podcasts have been produced with the support of

a range of junior and senior medical and healthcare

staff who reflect on their experiences of teamworking

and leadership in different capacities, with a strong

focus on primary care. Some of the materials have

been developed by senior students as part of their

Special Studies projects, which has been of benefit

to all parties. Reflection on performance is an integral

part of teaching and this is used not only to enhance

learning and consolidate understanding of teamwork

and leadership, but also to explore the principles of

professionalism. Relating campus-based teaching

to real examples from practice requires students

to consider issues of confidentiality, consent and

appropriate disclosure carefully, and allows the

tutor to intervene at an early stage to challenge

and discourage inappropriate behaviour. Exploring

attitudes and professional boundaries in a relatively

safe environment allows students to modify their

own behaviour at an early stage in the course.

Assessment of learning is on-going through group

presentations and projects, as well as through

completion of tasks and reflective exercises which

are entered into an e-portfolio. Students are also

required to complete 360-degree feedback to

encourage self-awareness and the ability to provide

constructive feedback to others which are essential

ingredients of effective leadership. Regular feedback

on e-portfolio exercises is given by the facilitator to

support the personal development of students and

to facilitate change as appropriate.

WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED?

The curriculum is now in the third year of delivery

and a number of changes have been made as a

result of student performance as well as feedback

from facilitators and students. Initially the concept of

leadership and organisational culture was introduced

in Year 1 and we found that this was too early in the

programme. The majority of students arrive straight

from school or college which limits the extent to

which they are able to reflect on experience of

leadership and management and appreciate these

concepts. Exploring these ideas at a later stage

allows students to bring their own placement

experience of leadership and management in action,

albeit predominantly from an observer perspective.

We have also found that having an emphasis on

leadership in the healthcare context engages

students more readily than using a wider range of

examples from other fields. It appears that students

come to medical school very keen to develop their

identity as trainee doctors and using materials

which support this are more likely to stimulate their

imagination. In addition, it enables facilitators to

identify more readily with the cases and supplement

them with examples from their own practice.

CONCLUSION

The integration of teaching on leadership and

management into the undergraduate curriculum

is essential but it is challenging in the light of the

maturity of students at this stage, and their relative

lack of experience of the world of work. Meeting

this challenge requires an interactive and engaging

approach to learning and teaching which centres

on experiential learning of teamworking initially,

with a later focus on leadership and management.

The spiral curriculum at Leeds allows this with the

integration of teaching on professionalism and

patient safety, alongside placement experience,

strengthening the self-awareness and efficacy of

students so that they develop an appreciation of

the words of Lao Tzu

14

Mastering others is strength,

mastering yourself is true power.

References

1 General Medical Council (2009) Tomorrows Doctors.

GMC: London. Available at: www.gmc-uk.org/publications

(accessed 16/10/12).

2 Darzi A (2008) High Quality of Care for All, NHS Next

Stage Review Final Report. Department of Health:

London.

3 General Medical Council (2006) Good Medical Practice.

GMC: London. Available at: www.gmc-uk.org/guidance

(accessed 16/10/12).

4 General Medical Council (2012) Leadership and

Management for all Doctors. GMC: London. Available at:

www.gmc-uk.org/publications (accessed 16/10/12).

5 NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2010)

Medical Leadership Competency Framework. Available

online at: www.institute.nhs.uk/medicalleadership

6 Department of Health (2012) NHS and Social Care Act.

DH: London.

7 Bruner J (1977) The Process of Education. Harvard

University Press: Massachusetts.

64 Teaching exchange

8 Bass BM and Rigio RE (2006) Transformational Leadership

(2e). Erlbaum: Mahwah, New Jersey.

9 Hersey P and Blanchard KH (1993) Management of

Organisational Behaviour: utilising human resources.

Prentice Hall: New Jersey.

10 McKim J and Philips K (2010) (eds) Leadership and

Management in Integrated Services. Learning Matters Ltd:

Exeter.

11 Goleman D, Boatzis R and McKee A (2001) Primal

Leadership, The Hidden Driver of Great Performance.

Harvard Business Review online at: www.hbr.org.

(accessed 16/10/12).

12 Alimo-Metcalfe B and Alban-Metcalfe J (2008) Research

Insight. Engaging Leadership: creating organisations that

maximise the potential of their people. Chartered Institute

of Personnel and Development: London.

13 Brockbank B, Farook S and Aegius S (2011) NHS

Leadership Framework: introduction, critique and

recommendations for practice. In: The Consultant, Issue

7 December 2011. Available at: www.theconsultantjournal.

co.uk (accessed 16/10/12).

14 Tzu Lao (1995) The Tao Te Ching of Lao Tzu. St Martins

Press: New York.

Correspondence to: Dr Anne-Marie Reid, Leeds

Institute of Medical Education, School of Medicine,

Worsley Building, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2

9NL, UK. Tel: +44 (0)113 343 1754; email: a.m.reid@

leeds.ac.uk

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Summary Poulfelt - Ethics For Management ConsultantsDokument3 SeitenSummary Poulfelt - Ethics For Management Consultantsbenjaminbollens1aNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lovaas BookDokument338 SeitenLovaas BooklicheiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Sales TechDokument9 Seiten10 Sales TechHamdy AlyNoch keine Bewertungen

- OYH Assessment ManualDokument53 SeitenOYH Assessment ManualLizPattison9275% (12)

- PSA 220 Long SummaryDokument6 SeitenPSA 220 Long SummaryKaye Alyssa EnriquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Lift Depression Quickly and SafelyDokument4 SeitenHow To Lift Depression Quickly and SafelyHuman Givens Publishing Official50% (2)

- Mapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - HealthDokument14 SeitenMapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - Healthgamms upNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cot DLP Science 6-Simple Machines With AnnotationsDokument9 SeitenCot DLP Science 6-Simple Machines With AnnotationsChii Chii100% (21)

- Wally Problem Solving Test Assessment DirectionsDokument13 SeitenWally Problem Solving Test Assessment DirectionsddfgfdgfdgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amina NazirDokument2 SeitenAmina NazirMuhammad NazirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Math 4 Week 6Dokument10 SeitenMath 4 Week 6Julie Ann UrsulumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparing Own Opinions with TextsDokument6 SeitenComparing Own Opinions with TextsMyra Fritzie Banguis100% (2)

- Neurodydaktyka WorkshopsDokument33 SeitenNeurodydaktyka WorkshopsKinga Gąsowska-SzatałowiczNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAPEH G08 1st Periodical TestDokument3 SeitenMAPEH G08 1st Periodical TestDana Reyes100% (2)

- Understanding Consumer Behavior: Hoyer - Macinnis - PietersDokument12 SeitenUnderstanding Consumer Behavior: Hoyer - Macinnis - PietersAngelo P. NuevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inner Health: A Journey Towards Self-Discovery: Dr. Falguni JaniDokument38 SeitenInner Health: A Journey Towards Self-Discovery: Dr. Falguni JaniAnonymous bkuFhRIHiqNoch keine Bewertungen

- July 2006, Vol 51, Supplement 2: Clinical Practice Guidelines Management of Anxiety DisordersDokument92 SeitenJuly 2006, Vol 51, Supplement 2: Clinical Practice Guidelines Management of Anxiety DisordersSendruc OvidiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ian Angel B. Osnan BECED III Ece 13: Science in Early Childhood Education Faculty: Ms. Dachel LaderaDokument4 SeitenIan Angel B. Osnan BECED III Ece 13: Science in Early Childhood Education Faculty: Ms. Dachel LaderaWowie OsnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Local and Regional Governance Module 3Dokument2 SeitenLocal and Regional Governance Module 3Tobby MendiolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essence of The Qualitative ApproachDokument4 SeitenEssence of The Qualitative ApproachNimi RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research into Coma, Esdaile and Sichort States offers New InsightsDokument10 SeitenResearch into Coma, Esdaile and Sichort States offers New Insightscoach rismanNoch keine Bewertungen

- EBIC Booklist2013Dokument7 SeitenEBIC Booklist2013celinelbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Huraian Sukatan Pelajaran Bahasa Inggeris Pendidikan Khas Week Date BIL KOD Standard Kandungan /pembelajaran Bi1 Greeting and Social ExpressionDokument8 SeitenHuraian Sukatan Pelajaran Bahasa Inggeris Pendidikan Khas Week Date BIL KOD Standard Kandungan /pembelajaran Bi1 Greeting and Social ExpressionMohd FadhliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Vital Role of Play in Early Childhood Education by Joan AlmonDokument35 SeitenThe Vital Role of Play in Early Childhood Education by Joan AlmonM-NCPPC100% (1)

- Writing A Concept Paper 190319200413Dokument24 SeitenWriting A Concept Paper 190319200413Julieto Sumatra JrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study On Metro RailDokument8 SeitenCase Study On Metro RailSidhant0% (1)

- Teacher Interview ResponseDokument6 SeitenTeacher Interview Responseapi-163091177Noch keine Bewertungen

- Brayton Polka Rethinking Philosophy in Light of The Bible From Kant To Schopenhauer PDFDokument186 SeitenBrayton Polka Rethinking Philosophy in Light of The Bible From Kant To Schopenhauer PDFNegru CorneliuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ratan Tata and His Enterprising SkillsDokument10 SeitenRatan Tata and His Enterprising Skillsstarbb100% (1)

- Lunenburg, Fred C. The Principal As Instructional Leader Imp PDFDokument7 SeitenLunenburg, Fred C. The Principal As Instructional Leader Imp PDFHania KhaanNoch keine Bewertungen