Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Why India Lags Behind China - Vox

Hochgeladen von

sanjeetvermaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Why India Lags Behind China - Vox

Hochgeladen von

sanjeetvermaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

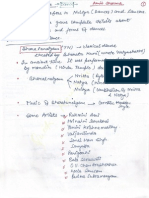

Why India lags behind China - vox

voxeu.org (http://www.voxeu.org/article/why-india-lags-behind-china)

What India must do to modernise

Arvind Panagariya, 15 January 2008

Historically, successful development has involved exporting labour-intensive

manufactures. Despite opening up to the world economy in many respects,

Indias policies continue to retard the expansion of labour-intensive sectors.

Here is a discussion of how India could speed its transition to a modern

economy.

a

A

A key advantage claimed for the outward-oriented development strategy is that

it allows poor, labour-abundant countries to specialise in labour-intensive

products and, thus make efficient use of limited capital stocks. To quote Anne O.

Kruger (1985), An export-oriented strategy permits countries to use the

international market to exchange their own, relatively labour-intensive

commodities for capital-intensive goods. They are thus able to take advantage of

the division of labour and specialisation. This ability contrasts sharply with

import-substitution policies under which labour-abundant developing countries

produce the entire spectrum of manufacturing goods and experience high and

rising capital/labour ratios.

The experiences of South Korea, Taiwan, Brazil and most recently China offer

broad support to this claim. Increasing shares of industry in GDP in general and

of labour-intensive manufactures in particular accompanied the adoption of

outward-oriented strategies in these countries. Exports of unskilled-labour-

intensive products such as apparel, footwear, toys and numerous light

manufactures expanded rapidly.

Indias recent engagement with the world economy has produced a contrasting

pattern, however. Contrary to the impression in many circles, Indias industrial

and services sectors are almost as open as those of China. The simple average of

industrial tariffs is 12% compared with 9% in China. The highest industrial tariff

rate (with tariff peaks in several sectors) has been brought down to 10%. In fiscal

year 2005-06, custom duty as a proportion of merchandise imports was just

4.9%. With some negative-list exceptionsmost notably multi-product retail

the goods and services sectors are quite open to foreign investment. Only in

exceptional cases such as insurance and media the sectoral cap on foreign

1

investment caps are below 51% and in most cases go up to 100%. While this

opening-up has been accompanied by acceleration in growth to 6.3% during the

last two decades and to almost 9% in the last four years, Indias experience

differs from that of China in at least three important respects. First, while India

has seen the share of agriculture in the GDP decline, it has not experienced

perceptible rise in the share of manufactures. Second, exports out of and direct

foreign investment (DFI) into India have not seen the same rapid expansion as

that seen in the case of China. Finally, fast-growing exports from India have been

either capital-intensive or skilled-labour intensive. The shift in favour of

unskilled-labour-intensive products traditionally observed in response to the

adoption of outward-oriented polices has not happened in India.

Indian exceptions

The share of manufacturing in the GDP in India has been stagnant at 17% since

the early 1990s. In China, this share stood at a hefty 41% in 2006. Indias

leading and fast-growing exports, such as engineering goods, petroleum

products, gems and jewelry, and software, are either capital-intensive or skilled-

labour intensive. The share of textiles and textile products in total merchandise

exports has declined to 15% in 2005-06 from 20% in 2003-04. Within this

category, unskilled-labour-intensive ready-made garments account for only half

of the exports. In contrast, the export pattern of China quickly adjusted to its

factor endowments after it began opening up its economy in the late 1970s and

early 1980s. First, exports of textiles, apparel, toys, sports goods and footwear

surged. Then in the 2000s, with rising skill endowments, it moved into more

sophisticated assembly operations such as office machinery,

telecommunications and electrical machinery.

The most dramatic difference between India and China lies in the magnitude of

international economic engagement. One measure of this difference is that the

annual expansion in Chinas trade has been larger than Indias total annual trade

during last several years. For instance, Chinas merchandise exports expanded

by $169 billion to $762 billion in 2005 in comparison to Indias total

merchandise exports of $103 billion in 2005-06. Equally dramatic are Figures 1

and 2 with the former showing the evolution of China and Indias two largest

merchandise exports and the latter depicting DFI inflows.

2

What holds back India?

How do we explain these differences in the response to trade openness of two

economies with very similar factor endowments? The key to answering this

question is the poor response of large-scale labour-intensive manufacturing

including assembly and processing activities in India. As per the conventional

wisdom, these activities have served as the magnet for DFI and a conduit for

rapid expansion of exports in China. But this has not happened in India. Large-

scale labour-intensive manufacturing activities have been virtually absent from

India. Apparel factories employing thousands of workers under a single roof

found in China are non-existent in India.

The explanation for the poor performance of large-scale labour-intensive

manufacturing is, in turn, to be found in the domestic policy regimeboth past

and present. Until the late 1980s, large Indian firms were confined to a positive

list of capital-intensive sectors. Even in these sectors, their size was limited

through licensing based on the perceived size of the domestic market by the

authorities. The same applied to foreign companies. These restrictions were

largely ended by the mega reforms of 1991 and those that immediately followed

them.

But this was insufficient to stimulate large-scale labour-intensive manufacturing.

In the late 1960s, India had also adopted the policy of reserving labour-intensive

manufactures for the exclusive production by small-scale enterprises. Even after

years of steady relaxation, the small-scale enterprises face a ceiling of 50 million

rupees (approximately $1.25 million) on investment in plant and machinery.

The small-scale industry list grew over time and by the late 1980s came to

include virtually all labour-intensive products.

As long as this reservation was in force, high-quality labour-intensive

manufactures that could compete on the world markets had no chance of

emerging in vast volumes. The bulk of the small-scale enterprises operated in

the protected domestic market. The problem was finally recognized in the late

1990s and the government began to gradually trim the Small Scale Industy list.

Even then progress was slow and the number of reserved items fell from 821 in

1998-99 to 114 in March 2007.

Most labour-intensive products including toys, footwear, sports goods and

apparel have now been off the reservation list for some years. More importantly,

even for products still on the list, large-scale production has been permitted

since at least March 2000 as long as the enterprise exports 50% or more of its

output. This latter change means that firms predominantly interested in

exporting their output have been free of such restrictions since March 2000. Yet,

labour-intensive manufacturing has remained stubbornly unresponsive.

The most important factor that still holds back large firms from entering these

products is a set of draconian labour laws in India. Under these laws, it is

virtually impossible for a firm with 100 or more employees to fire the workers

even in the face of bankruptcy. It is equally difficult for the firms to reassign the

workers from one task to another. These provisions impose very low worker

productivity or a high real cost of labour. Large-scale capital-intensive sectors

such as automobiles, where labour costs are a tiny proportion of the total costs,

can profitably operate in such an environment. But the same is not true of large-

scale labour-intensive sectors labour. Few foreign manufacturers are willing to

enter India outside of a small subset of capital- and skilled-labour intensive

sectors.

Two additional factors have held back the labour-intensive manufacturing in

India: costly power and poor transport infrastructure. Not only do firms pay a

much higher price for power in India than elsewhere in the world, they also face

much greater uncertainty of supply. Likewise, despite considerable

improvement, the transportation network in India remains unreliable and

inefficient. The time taken to clear the goods entering and existing the ports and

to move the goods between ports and manufacturing sites, which is so critical for

assembly and processing activities, is much higher and more variable in India

than in the competing countries such as China.

Indias path to modernisation

While high growth has helped India bring its poverty ratio (the proportion of the

poor below the official poverty line) down from 36% in 1993-94 to 27% in

2004-05, its transition to a modern economy remains problematic: it must still

move the vast majority of its workforce out of farming into non-farming

activities. With the services leg doing all of the walking, the economy can only

limp along towards this transition. For a more rapid transformation, India must

walk on two legs. That means more rapid growth of the labour-intensive

manufacturing.

References

Krueger, Anne O. 1985. The Experience and Lessons of Asias Super

Exporters, in Vittotio Corbo, Anne O. Krueger, and Fernando Ossa, editors,

Export Oriented Development Strategies, Boulder and London: Westview Press.

Panagariya, Arvind. 2008. India: The Emerging Giant, New York: Oxford

University Press.

Prasad, Eswar and Shang-Jin Wei. (2006). Understanding the Structure of Cross

border Capital Flows: The Case of China, presented at the conference, China

at Crossroads: FX and Capital Markets Policies for the Coming Decade, held at

the Columbia University on February 2-3, 2006.

Footnotes

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- HSC 405 Grant ProposalDokument23 SeitenHSC 405 Grant Proposalapi-355220460100% (2)

- ML BrochureDokument30 SeitenML BrochuresanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Count by 2s, and Fill in The Missing Numbers On Each Apple.: Date: 17/01/22 H.WDokument1 SeiteCount by 2s, and Fill in The Missing Numbers On Each Apple.: Date: 17/01/22 H.WsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 510 Mani Kant TiwariDokument2 Seiten510 Mani Kant TiwarisanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Dance-Quick Revision-1Dokument1 SeiteIndian Dance-Quick Revision-1AmitNoch keine Bewertungen

- 571 Maganbhai N BhagatDokument3 Seiten571 Maganbhai N BhagatsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fdi in Insurance Issues and Recent DevelopmentsDokument3 SeitenFdi in Insurance Issues and Recent DevelopmentssanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Details of Industrial Workers: Subash Chander-1 Subash Chander - 2 Ashwani KumarDokument1 SeiteDetails of Industrial Workers: Subash Chander-1 Subash Chander - 2 Ashwani KumarsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6 Take Care of The EarthDokument1 SeiteChapter 6 Take Care of The EarthsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 592 Amit PandeDokument4 Seiten592 Amit PandesanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 510 Mani Kant TiwariDokument2 Seiten510 Mani Kant TiwarisanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class 6 Science NCERT (Chapter 1-8) Part 1 Presented by Dr. Roman SainiDokument34 SeitenClass 6 Science NCERT (Chapter 1-8) Part 1 Presented by Dr. Roman SainisanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sub: Withdrawal of Application Under RTI Regarding M/s Indus Textile Mills Pvt. LTDDokument1 SeiteSub: Withdrawal of Application Under RTI Regarding M/s Indus Textile Mills Pvt. LTDsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aptitude Foundational Values For CSDokument15 SeitenAptitude Foundational Values For CSsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study: Deforestation in High Latitudes Could Lead To A 12% Decline in RainsDokument1 SeiteStudy: Deforestation in High Latitudes Could Lead To A 12% Decline in RainssanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Press Release June 05 2014 EngDokument2 SeitenPress Release June 05 2014 EngsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Current Affairs OCTOBER 2014: VisionDokument41 SeitenCurrent Affairs OCTOBER 2014: VisionsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Computer One LinerDokument23 SeitenComputer One LinerBineet Kumar VarmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agriculture MarketingDokument29 SeitenAgriculture MarketingsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Platinium Points RRB EnglishDokument28 SeitenPlatinium Points RRB Englishrs0728Noch keine Bewertungen

- Utilization Certificate I/r/o M/s Ajay Automatic & Printing WorksDokument1 SeiteUtilization Certificate I/r/o M/s Ajay Automatic & Printing WorkssanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Important Terms Franchise AgreementDokument3 SeitenImportant Terms Franchise AgreementsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 February 2014Dokument59 Seiten2 February 2014sanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hindu Review January 1Dokument12 SeitenThe Hindu Review January 1jyothishmohan1991Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fdi in Defence Issues and Recent DevelopmentsDokument3 SeitenFdi in Defence Issues and Recent DevelopmentssanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Franchise Recruitment ProcessDokument1 SeiteFranchise Recruitment ProcesssanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annexure VII & VII (A) - SIDBI FinancedDokument4 SeitenAnnexure VII & VII (A) - SIDBI FinancedsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AfspaDokument11 SeitenAfspasanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Press Release June 05 2014 EngDokument2 SeitenPress Release June 05 2014 EngsanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Lateral Recruitment of Credit Officers 2015Dokument11 Seiten2 Lateral Recruitment of Credit Officers 2015sanjeetvermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mahendra IntrvwprepDokument13 SeitenMahendra IntrvwprepMahammad RafeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- PC3 The Sea PeopleDokument100 SeitenPC3 The Sea PeoplePJ100% (4)

- Swami Rama's demonstration of voluntary control over autonomic functionsDokument17 SeitenSwami Rama's demonstration of voluntary control over autonomic functionsyunjana100% (1)

- Lightwave Maya 3D TutorialsDokument8 SeitenLightwave Maya 3D TutorialsrandfranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cs8791 Cloud Computing Unit2 NotesDokument37 SeitenCs8791 Cloud Computing Unit2 NotesTeju MelapattuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chemistry Implementation: Name: Rasheed Campbell School: Kingston College Candidate #.: Centre #: 100057Dokument12 SeitenChemistry Implementation: Name: Rasheed Campbell School: Kingston College Candidate #.: Centre #: 100057john brownNoch keine Bewertungen

- Update On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Dokument7 SeitenUpdate On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Sebastian DeMarinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADDRESSABLE 51.HI 60854 G Contoller GuideDokument76 SeitenADDRESSABLE 51.HI 60854 G Contoller Guidemohinfo88Noch keine Bewertungen

- India - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokument40 SeitenIndia - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaPrashanth KrishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Draft Initial Study - San Joaquin Apartments and Precinct Improvements ProjectDokument190 SeitenDraft Initial Study - San Joaquin Apartments and Precinct Improvements Projectapi-249457935Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDDokument81 Seiten1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDJerome Samuel100% (1)

- What Is DSP BuilderDokument3 SeitenWhat Is DSP BuilderĐỗ ToànNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aortic Stenosis, Mitral Regurgitation, Pulmonary Stenosis, and Tricuspid Regurgitation: Causes, Symptoms, Signs, and TreatmentDokument7 SeitenAortic Stenosis, Mitral Regurgitation, Pulmonary Stenosis, and Tricuspid Regurgitation: Causes, Symptoms, Signs, and TreatmentChuu Suen TayNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 - Soil-Only Landfill CoversDokument13 Seiten2 - Soil-Only Landfill Covers齐左Noch keine Bewertungen

- مقدمةDokument5 SeitenمقدمةMahmoud MadanyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Awakening The MindDokument21 SeitenAwakening The MindhhhumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compare Blocks - ResultsDokument19 SeitenCompare Blocks - ResultsBramantika Aji PriambodoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Apu Trilogy - Robin Wood PDFDokument48 SeitenThe Apu Trilogy - Robin Wood PDFSamkush100% (1)

- SOR 8th Ed 2013Dokument467 SeitenSOR 8th Ed 2013Durgesh Govil100% (3)

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Honda Bikes in CoimbatoreDokument43 SeitenA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Honda Bikes in Coimbatorenkputhoor62% (13)

- Lathe - Trainer ScriptDokument20 SeitenLathe - Trainer ScriptGulane, Patrick Eufran G.Noch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Week Heavy Slow Resistance Progression For Patellar TendinopathyDokument4 Seiten12 Week Heavy Slow Resistance Progression For Patellar TendinopathyHenrique Luís de CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rectifiers and FiltersDokument68 SeitenRectifiers and FiltersMeheli HalderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tds G. Beslux Komplex Alfa II (25.10.19)Dokument3 SeitenTds G. Beslux Komplex Alfa II (25.10.19)Iulian BarbuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap06 (6 24 06)Dokument74 SeitenChap06 (6 24 06)pumba1234Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arm BathDokument18 SeitenArm Bathddivyasharma12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fundermax Exterior Technic 2011gb WebDokument88 SeitenFundermax Exterior Technic 2011gb WebarchpavlovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mechanical Specifications For Fiberbond ProductDokument8 SeitenMechanical Specifications For Fiberbond ProducthasnizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Placenta Previa Case Study: Adefuin, Jay Rovillos, Noemie MDokument40 SeitenPlacenta Previa Case Study: Adefuin, Jay Rovillos, Noemie MMikes CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- IEEE T&D Insulators 101 Design CriteriaDokument84 SeitenIEEE T&D Insulators 101 Design Criteriasachin HUNoch keine Bewertungen