Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ian Bradley Talks LatheTools

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous mKdAfWif0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

162 Ansichten3 SeitenLatheTools

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenLatheTools

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

162 Ansichten3 SeitenIan Bradley Talks LatheTools

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous mKdAfWifLatheTools

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 3

NOVICES WORKSHOP

I an Bradl ey tal ks about

Lathe Tool s

THE NUMBER OF tools necessary to perform work

satisfactorily in the lathe is really very few. At one

time very comprehensive sets of tools were offered

for sale, many if not most of which the eventual

purchaser never used. These sets also had the dis-

advantage that the shanks of the tools themselves

were left in the rough forged condition, and not

ground flat on their underside which is generally

accepted as being best for ensuring a firm mounting

in the toolpost.

Today, however, one can buy tool bits that are

ground all over and, as they are bodily shaped, may

be used as they are, or clamped in a holder if need

be, the firmness of their mounting is assured, pro-

vided of course that the machine tool itself has no

shortcomings in this respect.

Varying types of steel are used in the making

of lathe and shaping machine tools. Originally

carbon steel was the main source of material but

with the advent of more difficult machining prob-

lems, and the need from the commercial aspect to

carry them out rapidly with the minimum of re-

sharpening, high-speed steels were introduced.

Tools made from this material are obtainable in the

forged condition if needed, in addition the tool

bits already referred to are made from high-speed

steel and are well worth the inevitable extra cost

involved.

In view of the advantages to be obtained from

the use of high-speed steel, it is perhaps not sur-

prising that tools made from carbon steel are losing

their favour even in the amateur workshop. One

form of carbon steel still fmds a use, however, this

is silver steel, available in round bright bar of vary-

ing diameters each 13 in. long. The material finds

an application in the making of cutters for various

purposes, since in the annealed state it is readily

machined and subsequently hardened and tempered

by quite primitive means. On the other hand, the

hardening and tempering of high-speed steel calls

for the employment of equipment most unlikely

to be found in the average small workshop, so tool

forming there is by a grinding process only.

AS stainless steel is now often found in the small

workshop, the employment of tools made from

high-speed steel is virtually essential. It is possible

to machine stainless material with carbon steel

tools, but their durability is then much reduced

and they rapidly lose their shape.

Carbide-tipped tools

The amateur workshop for the most part cannot

make the best use of carbide tools with one

exception, that is the tool used for machining

cast-iron. The reason for their failure, when used

on the light type of lathe possessed by most

amateurs, is that the carbide tip itself has little

mechanical strength, so, when it is not possible to

take a heavy cut, the chip produced by the turning

operation impinges directly on the cutting edge,

causing it to crumble.

When turning cast-iron, these conditions do not

apply. The chip produced breaks up immediately

on impact with the cutting edge and has then no

ill effect upon it. Carbide tools suitable for use in

the small workshop will be discussed later.

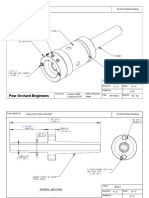

Fi g. 1 :

Nomenclature

of lathe

cutting tools.

Before dealing with specific tool shapes the terms

commonly applied to their angles must be con-

sidered. These are shown in Fig. 1. From this

illustration, where the tool is depicted in sections,

it will be seen that, in order to allow the tool to

cut in the direction shown in the diagram A, side

cl earance must be given or the tool will rub on the

work. Additionally to provide the correct cutting

angle for the material being machined, side rake

must be given to the tool point. Where viewed

from above the point of the tool will be seen to have

an angle of rel i ef; this is needed to prevent

chatter or vibration of the tool, the frontal area

of the tool in contact with the work being reduced

to the minimum consistent with obtaining a good

finish to the work surface. Front clearance must

also be given to the tool as shown at B, in order to

provide a satisfactory cutting angle.

Before leaving the subject of tool angle termino-

logy, one further condition needs to be considered.

This is the provision of negative rake to the tool

point as illustrated in Fig. 1 at C.

818 MODEL ENGI NEER 21 August 1970

T

From this diagram it will be seen that the top

surface of the tool is inclined at an angle above the

centre-line of the work. This practice is often

adopted industrially, but in the small workshop can

be employed with success when machining the

harder bronze alloys.

Tool shapes for external work

The basic tool shapes required are not many but

the few there are can be applied to a variety of tools

for both internal and external work. The first of

these is the roughing tool which probably needs

less power (despite its ability to take heavy cuts)

than any other. As an example of its effectiveness

Fig. 3 shows a roughing tool removing 7/ 16 in.

from a 3 in. billet of stainless steel. This machin-

ing operation was carried out at a mandrel speed

of 60 r.p.m. taking a cut of 0.005 in. per revolution

using a copious flow of neat cutting oil (Gulf

Metsil E) as a coolant. The lathe used was a 4 in.

Myford, now some 40 years old, and the driving

motor fitted was a 1/ 3 h.p. machine of a standard

commercial type.

- - - - D I R E C T I O N O F C U T -

-FRONT

Fig. 2 : Roughing and knife tools.

The knife tool

The most important weapon in the turners

armoury is the knife tool. It is found in both right-

handed and left-handed forms. The right-handed

knife tool cuts from right to left, that is to say it is

fed towards the headstock of the lathe, whilst its

counterpart the left-handed tool cuts in the opposite

direction. Fig. 2 depicts the salient characteristics

of a right-handed knife tool.

It is usual to grind a small flat land at the tip

of the tool. This area is at right-angles to the cutting

edge, helping to promote a good finish to the work.

As it is sometimes necessary to form a rounded

comer on shoulders machined by the knife tool,

the flat land can be replaced by a radial point, For

the amateur worker the radius of this point can

probably be standardised at some convenient figure

and it will therefore be convenient to have two

right-hncded knife tools to avoid the wastage of

material and the time involved in altering the point

of a single tool. An enlarged view of both forms of

point is seen in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

The parting tool

Once the worker has completed the turning of

a component he will need to sever it from the stock

material. This he does with the parting tool, shown

in Fig. 4. This is the form usually supplied in sets

of turning tools, but experienced workers modify

the point to ensure that the work is removed cleanly

and this alteration is shown at A. This is the tool

point commonly used in automatic lathes where,

of course, it is absolutely essential that the parts

produced are parted off cleanly.

Where much bar material turning is undertaken

the parting tool is best mounted in a toolpost set

on the cross-slide behind the work, thus leaving the

top-slide itself for holding outer turning tools either

singly or in a capstan head that may be indexed

accurately to bring a succession of tools to bear on

the work as required. It is perhaps worth em-

phasising that the back toolpost, as it is called,

is the ideal holder for parting tools in a light lathe

because the forces then acting tend to force the

faces of the cross-slide into closer contact. In this

way vibration sometimes encountered in the front-

of-work placing of the tool can usually be elimin-

MODEL ENGINEER 21 August 1970

819

FLAT

POI NT

ROUNDED

POI NT

-3O

FOR STEEL 3 IO0 RAKE

-

4 L-80

Fig. 4.

ated. Long ago Duplex advocated this position

and designed a toolpost that itself possessed a

capstan-head. carrying a pair of tools, one for

chamfering and one for parting-off, two operations

regularly needed. A typical set-up embracing front

and rear tool placings in capstan-heads is illustrated

in Fig. 5.

The screwcutting tool

The last of the basic tools needed for external

work is the screwcutting tool whose salient features

are seen in Fig. 4 above.

The point angle depends upon the thread form

to be cut. In this context the handbook Screw

Threads and Twist Drills published by Model &

Allied Publications may be consulted. It should

be noted however that as supplied, commercial

single-point threading tools are not necessarily

ground to any particular angle. One must be care-

ful, therefore, to check this angle using the appro-

priate setting gauge for the purpose. This gauge,

illustrated in Fig. 6, is provided with male and

female cones of the correct angle so that the accur-

WORK

c

GAUGE

Fig. 7

ROUGHING

FINISHING

acy of the tool point can be checked. In addition

the sides of the device have angular notches, again

of the correct angle, machined in them to enable

the turner to set the threading tool squarely with

the work. This he does by placing the gauge against

the side of the part and engaging the tool point

with one of the notches in the manner shown by

the illustration Fig. 7.

A piece of white paper or card placed below the

tool point will enable the correct engagement of

the tool point with the notch to be observed more

easily. To be continued.

820

MODEL ENGINEER 21 August 1970

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Construction and Manufacture of AutomobilesVon EverandConstruction and Manufacture of AutomobilesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Functional Composite Materials: Manufacturing Technology and Experimental ApplicationVon EverandFunctional Composite Materials: Manufacturing Technology and Experimental ApplicationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Milling Attachment With 3 FunctionsDokument3 SeitenMilling Attachment With 3 FunctionsKarthickNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2847-Keys & Driving PinsDokument1 Seite2847-Keys & Driving PinssyllavethyjimNoch keine Bewertungen

- 149-Workshop Hints & Tips PDFDokument1 Seite149-Workshop Hints & Tips PDFsyllavethyjimNoch keine Bewertungen

- 149-Workshop Hints & TipsDokument1 Seite149-Workshop Hints & TipssyllavethyjimNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2873-Cotters & Wedges PDFDokument1 Seite2873-Cotters & Wedges PDFsyllavethyjimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cutting Force MarbleDokument8 SeitenCutting Force MarbleGhiyath WaznehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contours 1: Hile It CannotDokument1 SeiteContours 1: Hile It CannotsyllavethyjimNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2943-Port & Valve TimingDokument1 Seite2943-Port & Valve TimingVinoth Kumar VinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 9 Physics - Steam Engine (Reporting)Dokument26 SeitenGrade 9 Physics - Steam Engine (Reporting)Ionacer ViperNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cb750k EngineDokument57 SeitenCb750k Enginepaul balfeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lathe ToolslideDokument2 SeitenLathe ToolslideFrenchwolf420Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2924-Balancing Single Cylinder EnginesDokument1 Seite2924-Balancing Single Cylinder Enginesquartermiler6Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lathebeddesign00hornrich PDFDokument56 SeitenLathebeddesign00hornrich PDFLatika KashyapNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2965-Lapping Tapers & Seatings #7Dokument1 Seite2965-Lapping Tapers & Seatings #7syllavethyjimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shaper Used As Surface GrinderDokument1 SeiteShaper Used As Surface Grinderradio-chaserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engineering Vol 69 1900-03-16Dokument30 SeitenEngineering Vol 69 1900-03-16ian_newNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2947 Simple PatternmakingDokument1 Seite2947 Simple PatternmakingSandra Barnett CrossanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dapra Biax Article Art of ScrapingDokument2 SeitenDapra Biax Article Art of ScrapingPedro Ernesto SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cowells Manuals PDFDokument16 SeitenCowells Manuals PDFpedjaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2012 GrapesDokument3 Seiten2012 Grapesvorotyn_9479661530% (1)

- Engineering Vol 56 1893-11-10Dokument35 SeitenEngineering Vol 56 1893-11-10ian_newNoch keine Bewertungen

- ReamersDokument1 SeiteReamersvikash kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engineering Vol 56 1893-12-15Dokument33 SeitenEngineering Vol 56 1893-12-15ian_newNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grinding MachinesDokument140 SeitenGrinding MachinesyowiskieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quorn: Tool and Cutter GrinderDokument4 SeitenQuorn: Tool and Cutter GrinderDan HendersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shaper Cut GearsDokument5 SeitenShaper Cut GearstaiwestNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metal Spinning PDFDokument86 SeitenMetal Spinning PDFloosenut100% (1)

- Syllabus For The Trade Of: Machinist (Grinder)Dokument27 SeitenSyllabus For The Trade Of: Machinist (Grinder)swami061009Noch keine Bewertungen

- WErbsen CourseworkDokument562 SeitenWErbsen CourseworkRoberto Alexis Rodríguez TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04 80 PDFDokument272 Seiten04 80 PDFRahmat Budi PermanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brunell CatalogueDokument36 SeitenBrunell CataloguePaul HartlandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of Shell StructureDokument37 SeitenAnalysis of Shell StructureDave Mark AtendidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Machinists Tools by Williams 1944Dokument32 SeitenMachinists Tools by Williams 1944OSEAS GOMEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drill Vise MillDokument2 SeitenDrill Vise MillFrenchwolf420Noch keine Bewertungen

- (B) Testing Machine ToolsDokument100 Seiten(B) Testing Machine ToolsHyeonggil JooNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2886-Stud Fitting & Removal PDFDokument1 Seite2886-Stud Fitting & Removal PDFsyllavethyjimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ebook Tapping Away Guide To Tapping and Threading Xometry SuppliesDokument19 SeitenEbook Tapping Away Guide To Tapping and Threading Xometry SuppliesAli KhubbakhtNoch keine Bewertungen

- 31B6E TurningDokument26 Seiten31B6E Turningwienslaw5804100% (1)

- Acoustic Tractor Beam: 35 Steps (With Pictures) PDFDokument38 SeitenAcoustic Tractor Beam: 35 Steps (With Pictures) PDFAmirNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2895-Different Types of PumpsDokument1 Seite2895-Different Types of PumpsDinkalai WaronfireNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Stroke Diesel EngineDokument16 Seiten6 Stroke Diesel EngineadityaguptaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Center Punch Grinding JigDokument2 SeitenCenter Punch Grinding JigmododanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tread Hammer RahulDokument36 SeitenTread Hammer RahulHemant MaheshwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quick Change Gearbox: Instructions For Installation and Operation Pictorial Parts ListDokument10 SeitenQuick Change Gearbox: Instructions For Installation and Operation Pictorial Parts ListhrjeldesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2878-Chains & Sprockets PDFDokument1 Seite2878-Chains & Sprockets PDFsyllavethyjimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anyang Power HammerDokument7 SeitenAnyang Power HammeraguswNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aferican Oxcart Design and ManufactureDokument62 SeitenAferican Oxcart Design and ManufacturereissmachinistNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACESORIOScatalog PDFDokument80 SeitenACESORIOScatalog PDFlmelmelmeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 33 - Making Clocks PDFDokument65 Seiten33 - Making Clocks PDFBruno DelsupexheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sheet MetalDokument5 SeitenSheet MetalAlapati PrasadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steam TurbineDokument7 SeitenSteam TurbineakmalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Failure Analysis of A Coil SpringDokument7 SeitenFailure Analysis of A Coil SpringCiobanu MihaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- South Bend 10LathesCatalogDokument14 SeitenSouth Bend 10LathesCatalogdsr200100% (1)

- Louis Belet Cutting Tools Watchmaking Jura Suisse Vendlincourt Switzerland Brochure Hob Cutters enDokument16 SeitenLouis Belet Cutting Tools Watchmaking Jura Suisse Vendlincourt Switzerland Brochure Hob Cutters enLogan RaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pear Orchard Engineers: Do Not Scale Drawing Part Used OnDokument4 SeitenPear Orchard Engineers: Do Not Scale Drawing Part Used OnAnonymous mKdAfWifNoch keine Bewertungen

- En Metalwork General Metal WorkDokument90 SeitenEn Metalwork General Metal WorkAnonymous mKdAfWifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Primena 3D Stampe U ObrazovanjuDokument4 SeitenPrimena 3D Stampe U ObrazovanjuAnonymous mKdAfWifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zadatak 1a Vitlo SkidDokument2.018 SeitenZadatak 1a Vitlo SkidAnonymous mKdAfWifNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Few Project Images: Tool Posts Lathe Cutting ToolsDokument4 SeitenA Few Project Images: Tool Posts Lathe Cutting ToolsAnonymous mKdAfWifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Casting Elwany FullDokument22 SeitenCasting Elwany FullAnonymous mKdAfWifNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 MaterialsDokument6 Seiten01 MaterialsAnonymous mKdAfWifNoch keine Bewertungen

- SilencerDokument4 SeitenSilencerAnonymous mKdAfWif0% (1)

- Preview Thread CuttingDokument21 SeitenPreview Thread CuttingAnonymous mKdAfWif33% (3)

- Pedia 2017 Case ProtocolDokument14 SeitenPedia 2017 Case ProtocolArjay Amba0% (1)

- Truss Design GuidDokument3 SeitenTruss Design GuidRafi HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microbiology QuestionsDokument5 SeitenMicrobiology QuestionsNaeem AminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baby Checklist: Room Furniture Baby Wear Baby BeddingDokument2 SeitenBaby Checklist: Room Furniture Baby Wear Baby BeddingLawrence ConananNoch keine Bewertungen

- Naplan Year 9 PracticeDokument23 SeitenNaplan Year 9 PracticetonynuganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Mechanical Engineering Btkit Dwarahat: Attempt All Questions. Q. 1. Attempt Any Four Parts: 5 X 4 20Dokument2 SeitenBasic Mechanical Engineering Btkit Dwarahat: Attempt All Questions. Q. 1. Attempt Any Four Parts: 5 X 4 20anadinath sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modding For Ysflight - Scenery EditorDokument92 SeitenModding For Ysflight - Scenery Editordecaff_42Noch keine Bewertungen

- Research Article: International Research Journal of PharmacyDokument5 SeitenResearch Article: International Research Journal of PharmacyAlfrets Marade SianiparNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answer To Question-1: Agricultural ApplicationsDokument7 SeitenAnswer To Question-1: Agricultural ApplicationsSoham ChaudhuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- ClimateDokument38 SeitenClimateCristine CaguiatNoch keine Bewertungen

- C8 Flyer 2021 Flyer 1Dokument7 SeitenC8 Flyer 2021 Flyer 1SANKET MATHURNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fortified Rice FssaiDokument8 SeitenFortified Rice FssaisaikumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constructing 30deg AngleDokument4 SeitenConstructing 30deg AngleArthur ChewNoch keine Bewertungen

- CO Q1 TLE EPAS 7 8 Module 4 Preparing Technical DrawingsDokument47 SeitenCO Q1 TLE EPAS 7 8 Module 4 Preparing Technical DrawingsNicky John Doroca Dela MercedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cross Border Pack 2 SumDokument35 SeitenCross Border Pack 2 SumYến Như100% (1)

- Theories of DissolutionDokument17 SeitenTheories of DissolutionsubhamNoch keine Bewertungen

- INERT-SIEX 200-300 IG-100: Design ManualDokument54 SeitenINERT-SIEX 200-300 IG-100: Design ManualSaleh Mohamed0% (1)

- 4200 Magnetometer Interface Manual 0014079 - Rev - ADokument34 Seiten4200 Magnetometer Interface Manual 0014079 - Rev - AJose Alberto R PNoch keine Bewertungen

- Homework 3rd SteelDokument4 SeitenHomework 3rd SteelPiseth HengNoch keine Bewertungen

- BR18S-7 Manual CracteristicasDokument10 SeitenBR18S-7 Manual Cracteristicasrendimax insumos agricolasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Standard Safety Practices Manual PDFDokument350 SeitenStandard Safety Practices Manual PDFsithulibraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wanderer Above The Sea of FogDokument5 SeitenWanderer Above The Sea of FogMaria Angelika BughaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ayurvedic Vegan Kitchen PDFDokument203 SeitenThe Ayurvedic Vegan Kitchen PDFRuvaly MzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kyocera Mita KM1505 1510 1810 Series ELITEC EssentialsDokument6 SeitenKyocera Mita KM1505 1510 1810 Series ELITEC EssentialsJaime RiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Balance Diet and NutritionDokument9 SeitenBalance Diet and NutritionEuniceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Custard The DragonDokument4 SeitenCustard The DragonNilesh NagarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Table of Content and PrefaceDokument5 SeitenTable of Content and PrefaceHaiderEbrahimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module I: Introduction To Environmental PollutionDokument14 SeitenModule I: Introduction To Environmental PollutionAman John TuduNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is MetaphysicsDokument24 SeitenWhat Is MetaphysicsDiane EnopiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edc Contractors Basic Safety Training: "New Normal" EditionDokument8 SeitenEdc Contractors Basic Safety Training: "New Normal" EditionCharles Rommel TadoNoch keine Bewertungen