Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Philippine Lit

Hochgeladen von

Axle Ross BartolomeOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Philippine Lit

Hochgeladen von

Axle Ross BartolomeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This Nation Can Be Great Again by Ferdinand E.

Marcos

Each generation writes his own history. Our forbears have written theirs. With fortitude and excellence

we must write ours.

We must renew the vision of greatness for our country. This is a vision of our people rising above the

routine to face formidable challenges and overcome them. It means the rigorous pursuit of excellence.

It is a government that acts as the guardian of the laws majesty, the source of justice to the weak and

solace to the underprivileged a ready friend and protector of the common man and a sensitive

instrument of his advancement and not captivity.

This vision rejects and discards the inertia of centuries.

It is a vision of the jungles opening up to the farmers tractor and plow, and the wilderness claimed for

agriculture and the support of human life; the mountains yielding their boundless treasure, rows of

factories turning the harvests of our fields into a thousand products.

It is the transformation of the Philippines into a hub of progress of trade and commerce in Southeast

Asia.

It is our people bravely determining our own future. For to make the future is the supreme act of the

free.

This is a vision that all of you share for our countrys future. It is a vision which can and should, engage

the energies of the nation. This vision must touch the deeper layers of national vitality and energy.

We must awake the hero inherent in every man.

We must harness the wills and the hearts of all our people. We must find the secret chords which turn

ordinary men into heroes, mediocre fighters into champions.

Not one hero alone do I ask from you but many; nay all. I ask all of you to be the heroes of our nation.

Offering all our efforts to our Creator, we must drive ourselves to greatness.

This is your dream and mine. By your choice you have committed yourselves to it. Come then, let us

march together towards the dream of greatness.

Vacation days at last are here,

And we have time for fun so dear,

All boys and girls do gladly cheer,

This welcomed season of the year.

In early June in school well meet;

A harder task shall we complete

And if we fail we must repeat

That self same task without retreat.

We simply rest to come again

To school where boys and girls obtain

The Creators gift to men

Whose sanguine hopes in us remain.

Vacation means a time for play

For young and old in night and day

My wish for all is to be gay,

And evil none lead you astray

- Juan F. Salazar Philippines Free Press, May 9, 1909

ANG MAGANDANG PAROL

Isang papel itong ginawa ng lolo

may pula, may asul, may buntot sa dulo;

sa tuwing darating ang masayang Pasko

ang parol na itoy makikita ninyo.

Sa aming bintana doon nakasabit

kung hipan ng hangiy tatagi-tagilid,

at parang tao ring bago na ang bihis

at sinasalubong ang Paskong malamig.

Kung kamiy tutungo doon sa simbahan

ang parol ang aming siyang tagatanglaw,

at kung gabi namang malabo ang buwan

sa tapat ng parol doon ang laruan.

Kung aking hudyatin tanang kalaguyo,

mga kapwa bata ng pahat kong kuro,

ang aming hudyatan ay mapaghuhulo:

Sa tapat ng lolo tayo maglalaro.

Kaya nang mamatay ang lolo kong yaon,

sa bawat paghihip ng amihang simoy,

iyang nakasabit na naiwang parol

nariyan ang diwa noong aming ingkong.

Nasa kanyang kulay ang magandang nasa,

nasa kanyang ilaw ang dakilang diwa,

parang sinasabi ng isang matanda:

Kung wala man akoy tanglawan ang bata.

This poem was published 81 years ago in Taliba. December 20, 1928.

ANG TREN

Tila ahas na nagmula

sa himpilang kanyang lungga,

ang galamay at palikpik, pawang bakal, tanso, tingga,

ang kaliskis, lapitan mot mga bukas na bintana.

Ang rail na lalakaray

nakabalatay sa daan,

umaaso ang bunganga at maingay na maingay,

sa Tutuban magmumulat patutungo sa Dagupan.

O, kung gabit masalubong

ang mata ay nag-aapoy,

ang silbato sa malayoy dinig mo pang sumisipol

at hila-hila ang kanyang kabit-kabit namang bagon.

Walang pagod ang makina,

may baras na nasa rweda,

sumisingaw, sumisibad, humuhuni ang pitada,

tumetelenteng ang kanyang kainpanada sa tuwina.

Kailan ka magbabalik?

Hanggang sa hapon ng Martes.

At tinangay na ng tren ang naglakbay na pag-ibig,

sa bentanilyay may panyot may naiwang nananangis.

BAYAN KO

Ang bayan kong Pilipinas

Lupain ng ginto't bulaklak

Pag-ibig na sa kanyang palad

Nag-alay ng ganda't dilag.

At sa kanyang yumi at ganda

Dayuhan ay nahalina

Bayan ko, binihag ka

Nasadlak sa dusa.

Ibon mang may layang lumipad

kulungin mo at umiiyak

Bayan pa kayang sakdal dilag

Ang di magnasang makaalpas!

Pilipinas kong minumutya

Pugad ng luha ko't dalita

Aking adhika,

Makita kang sakdal laya.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Ang bayan kong Pilipinas

My country that is the Philippines

Lupain ng ginto't bulaklak

Land of gold and flowers

Ibon mang may layang lumipad

Even a bird with the freedom to fly

kulungin mo at umiiyak

cage it and it cries

Pugad ng luha ko

Nest of my tears

Bayan ba kayang sakdal dilag

What more a country totally exquisite

Aking adhika

My desire

Makita kang sakdal laya

To see you completely free

KAHIT SAAN

Kung sa mga daang nilalakaran mo,

may puting bulaklak ang nagyukong damo

na nang dumaan ka ay biglang tumungo

tila nahihiyang tumunghay sa iyo. . .

Irog, iyay ako!

Kung may isang ibong tuwing takipsilim,

nilalapitan ka at titingin-tingin,

kung sa iyong silid masok na magiliw

at ikay awitan sa gabing malalim. . .

Ako iyan, Giliw!

Kung tumingala ka sa gabing payapa

at sa langit namay may ulilang tala

na sinasabugan ikaw sa bintana

ng kanyang malungkot na sinag ng luha

Iyay ako, Mutya!

Kung ikawy magising sa dapit-umaga,

isang paruparo ang iyong nakita

na sa masetas mong didiligin sana

ang pakpak ay wasak at nanlalamig na. . .

Iyay ako, Sinta!

Kung nagdarasal kat sa matang luhaan

ng Kristoy may isang luhang nakasungaw,

kundi mo mapahid sa panghihinayang

at nalulungkot ka sa kapighatian. . .

Yaoy ako, Hirang!

Ngunit kung ibig mong makita pa ako,

akong totohanang nagmahal sa iyo;

hindi kalayuan, ikaw ay tumungo

sa lumang libingat doon, asahan mong. . .

magkikita tayo!

Philippine Literature

The Rebirth of Freedom (1946-1970)

Historical Background

The Americans returned in 1945. Filipinos rejoiced and guerillas who fled to the

mountain joined the liberating American Army.

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines regained is freedom and the Filipino flag waved

joyously alone. The chains were broken.

A. THE STATE OF LITERATURE DURING THIS PERIOD

The early post-liberation period was marked by a kind of struggle of mind and

spiritposed by the sudden emancipation from the enemy, and the wild desire to see

print.

Filipinos had, by this time, learned to express themselves more confidently but post-

war problems beyond language and print-like economic stability, the threat of new

ideas and mortality had to be grappled with side by side.

There was a proliferation of newspapers like the FREE PRESS, MORNING SUN, of Sergio

Osmea Sr., DAILY MIRROR of Joaquin Roces, EVENING NEWS of Ramon Lopezes and the

BULLETIN of Menzi. This only proved that there were more readers in English than in

any ocher vernaculars like Tagalog, Ilocano or Hiligaynon.

Journalists had their day. They indulged in more militant attitude in their reporting

which bordered on the libelous. Gradually, as normality was restored, the tones and

themes of the writings turned to the less pressing problems of economic survival.

Some Filipino writers who had gone abroad and had written during the interims came

back to publish their works.

Not all the books published during the period reflected the war year; some were

compilations or second editions of what have been written before.

Some of the writers and their works of the periods are:

THE VOICE OF THE VETERAN a compilation of the best works of some Ex-USAFFE men like

Amante Bigornia, Roman de la Cruz, Ramon de Jesus and J.F. Rodriguez.

TWILIGHT IN TOKYO andPASSION and DEATH OF THE USAFFE by Leon Ma. Guerrero

FOR FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACYby S.P. Lopez

BETRAYAL IN THE PHILIPPINESby Hernando Abaya

SEVEN HILLS AWAYby NVM Gonzales

POETRY IN ENGLISH DURING THIS PERIOD

For the first twenty years, many books were publishedboth in Filipino and in English.

Among the writers during this time were: Fred Ruiz Castro, Dominador I. Ilio, and C.B.

Rigor.

Some notable works of the period include the following:

1. HEART OF THE ISLANDS (1947) a collection of poems by Manuel Viray

2. PHILIPPINES CROSS SECTION (1950) a collection of prose and poetry by Maximo Ramos

and Florentino Valeros

3. PROSE AND POEMS (1952) by Nick Joaquin

4. PHILIPPINE WRITING (1953) by T.D. Agcaoili

5. PHILIPPINE HAVEST by Amador Daguio

6. HORIZONS LEAST (1967) a collection of works by the professors of UE, mostly in

English (short stories, essays, research papers, poem and drama) by Artemio Patacsil

and Silverio Baltazar

The themes of most poems dealt with the usual love of nature, and of social and

political problems. Toribia Maos poems showed deep emotional intensity.

7. WHO SPOKE OF COURAGE IN HIS SLEEP by NVM Gonzales

8. SPEAK NOT, SPEAK ALSO by Conrado V. Pedroche

9. Other poets were Toribia Mao and Edith L. Tiempo

Jose Garcia Villas HAVE COME, AM HEREwon acclaim both here and abroad.

NOVELS AND SHORT STORIES IN ENGLISH

Longer and longer pieces were being written by writers of the period. Stevan

Javellanas WITHOUT SEEING THE DAWN tells of the grim experiences of war during the

Japanese Occupation.

In 1946, the Barangay Writers Project whose aim was to publish works in English by

Filipinos was established.

In 1958, the PEN Center of the Philippines (Poets, essayists, novelists) was

inaugurated. In the same year, Francisco Arcellana published his PEN ANTHOLOGY OF

SHORT STORIES.

In 1961, Kerima Polotans novel THE HAND OF THE ENEMY won the Stonehill Award for the

Filipino novel in English.

In 1968, Luis V. Teodoro Jr.s short story THE ADVERSARY won the Philippines Free

Press short story award; in 1969, his story THE TRAIL OF PROFESSOR RIEGO won second

prize in the Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature and in 1970, his short story THE

DISTANT CITY won the GRAPHIC short story award.

THE NEW FILIPINO LITERATURE DURING THIS PERIOD

Philippines literature in Tagalog was revived during this period. Most themes in the

writings dealt with Japanese brutalities, of the poverty of life under the Japanese

government and the brave guerilla exploits.

Newspapers and magazine publications were re-opened like the Bulaklak, Liwayway, Ilang

Ilangand Sinag Tala. Tagalog poetry acquired not only rhyme but substance and meaning.

Short stories had better characters and events based on facts and realities and themes

were more meaningful. Novels became common but were still read by the people for

recreation.

The peoples love for listening to poetic jousts increased more than before and people

started to flock to places to hear poetic debates.

Many books were published during this time, among which were:

1. Mga Piling Katha (1947-48) by Alejandro Abadilla

2. Ang Maikling Kuwentong Tagalog (1886-1948) by Teodoro Agoncillo

3. Akoy Isang Tinig (1952) collection of poems and stories by Genoveva Edroza Matute

4. Mga Piling Sanaysay (1952) by Alejandro Abadilla

5. Maikling Katha ng Dalawampung Pangunahing Autor (1962) by A.G. Abadilla and

Ponciano E.P. Pineda

6. Parnasong Tagalog (1964) collection of selected poems by Huseng Sisiw and Balagtas,

collected by A.G. Abadilla

7. Sining at Pamamaraan ng Pag-aaral ng Panitikan (1965) by Rufino Alejandro.

He prepared this book for teaching in reading and appreciation of poems, dramas, short

stories and novels

8. Manlilikha, Mga Piling Tula (1961-1967) by Rogelio G. Mangahas

9. Mga Piling Akda ng Kadipan (Kapisanang Aklat ng Diwa at Panitik) 1965 by Efren

Abueg

10. Makata (1967) first cooperative effort to publish the poems of 16 poets in

Pilipino

11. Pitong Dula (1968) by Dionisio Salazar

12. Manunulat: Mga Piling Akdang Pilipino (1970) by Efren Abueg. In this book, Abueg

proved that it is possible to have a national integration of ethnic culture in our

country.

13. Mga Aklat ni Rizal: Many books about Rizal came out during this period. The law

ordering the additional study of the life of Rizal helped a lot in activating our

writers to write books about Rizal.

The Judge

Rabindranath Tagore

Translated from the original Bengali by

Saurav Bhattacharya

First episode

Even the partner that middle-aged Khiroda had found at long last after passing

through many circumstances abandoned her like a piece of torn cloth. She detested

with all her heart the prospect of attempting to search for food and shelter for a second

time.

At the end of youth, comes like the clear autumn, a profound and beautiful age, when

it is time for the fruits and grains of life to ripen. At that age, the agility of the wild

youth no longer seems appropriate. By that time, we have had already built our

homes; many good and evil, happiness and sorrow have been cooked in the cauldron

of life, making the inner-self matured; we have, by then, put our stray ambitions on

leash and have established them within the four walls of our modest abilities, dragging

them back from the dreamland of the unachievable; at that time it is no longer

possible to attract the charmed look of a new found love; but people tend to become

more dearer to the long-known and familiar. Youthful charm, by then, has slowly

started giving way; but by long association with the body the fit inner-self expresses

itself more prominently on the face and eyes - through the smiles, the looks, the voice.

Leaving hope for things we didnt get, ending bereavement for the departed, forgiving

those that deceived, we seek solace among those who have been near, who have

loved, who have remained close withstanding the vagaries of life; we build safe nests

in the loving embrace of those few close, time-tested and familiar beings and see

therein the culmination of all our efforts and the fulfilment, of all our longings. In that

dusk of youth, in the peace of that stage of life, he who has to start again in the false

hope of new gains, new acquaintances and new relationships for whose rest the bed

has yet to be spread for whom no light has been lit to welcome him home at day end

cursed indeed is he.

At the brink of her youth, one morning, when Khiroda woke up to find that her fianc

had run off the last night with all her ornaments and money, to leave her with not

enough even to pay the rent or to get some milk to feed her three-year old child she

reminisced that in her life of thirty-eight years she could not lay claim over a single

man, she had not acquired the right to live or die in the corner of any room. She

realised she would again have to wipe off tears to deck up her eyes with black kajol

and put on red make-up on her lips and cheeks in a curious attempt to cover up the

worn-out youth and devise new schemes cheerfully and with infinite patience to

capture new hearts. She locked herself up in her room and started repeatedly banging

her head against the hard floor she remained there throughout the day without

touching any food. Outside it grew dark. Inside the room, with no lamp lit, the

darkness concentrated. As chance would have it, an old fianc came over and started

knocking at her door, calling Khiro, Khiro. Roaring like a tigress, Khiroda

suddenly sprang up and started for the man with a broom in her hand; the love-thirsty

youth had to look for escape without wasting any time. The child, bitten by the pangs

of hunger, had fallen asleep under the bed after crying for some time. He woke up in

the commotion and started crying in a broken voice , Ma! Ma!

At that juncture Khiroda picked up her child, held him fast against her breast and

running at lightning speed jumped into a nearby well. Alerted by the sound,

neighbours came up with lamps and gathered around the well. It did not take long to

fish up Khiroda and her child. Khiroda was unconscious and the child had died.

Khiroda recovered in the hospital. The magistrate transferred her case to the session

court on charge of murder.

Second episode

Judge Mohitmohun Dutt, Statutory Civilian. In his ruthless judgment Khiroda was

sentenced to death by hanging. Lawyers, moved by her wretched condition, tried their

best to save her but without success. The judge could not consider her to be worthy of

even a bit of mercy.

There was reason enough for that. Though the judge attributed Godly characteristics

to Hindu women, his lack of trust on women as a class was straight from his heart. He

was of the view that women are ever eager to sever all ties with their families; even a

slight relaxation in governing them would result in not a single chaste woman being

left in the society.

This belief of the judge also had a basis. To appreciate that, it is necessary to throw

light upon a part of the history of Mohits early life.

In the second year of his college, Mohit had been an entirely different person in

appearance and manners. Mohit is now bald in the front-head, sports a tuft at the back,

and his face is smooth with the thorough shave that he has every morning; but then

with gold-rimmed glasses, beard and moustache and hair dressed in true European

style, Mohit was like a new version of Kartik of the Nineteeenth-century.

He was quite conscious of his dress, did not detest drinking and dining and also had a

few concomitant vices.

A family stayed nearby. They had a widowed daughter called Hemshoshi. She was

young aged fourteen going on fifteen.

The tree-lined shore does not seem as picturesque and soothing from the land as it

seems from the sea. Widowhood created a distance between family life and

Hemshoshi. That distance made Hemshoshi view family life as a house of

entertainment, full of deep mystery, on the distant other shore. She did not know that

the nuts and bolts of this world are extremely complicated and iron-hard a mixture

of happiness and sorrow, wealth and poverty, uncertainty, danger, frustration and

repentance. She used to think that family life was as easy as the crystal clear flow of

the murmuring stream; that every road in the beautiful world is wide and straight; that

happiness lies just outside her window while all unfulfilled desires reside deep within

her soft warm heart, throbbing in her breast. Specially, at that time, a whiff of fresh air

carrying the scent of youth would arise from the distant horizon of her mind and blow

over the entire world giving it a touch of spring. The vibration of her heart would

travel the entire stretch of the blue sky and the earth would bloom around her fragrant

heart in layers like the soft petals of a red lotus.

At home, she had nobody except her parents and two younger brothers. The brothers

would leave early for school after breakfast and would again go after supper to the

nearby night school to practise lessons. The father used to earn a pittance and could

not afford to pay for tuitions at home.

In the intervals from work Hem would come and rest in her empty room. She would

watch intently people move up and down the main road; she would listen to the

hawker crying out entreating people to purchase his wares; and she would think that

people on the street were all content, that even beggars were all free and that the

hawkers were not really engaged in a fight for survival they were just actors, happily

enacting on a stage a play of simple movements..

And every morning and evening she would see the immaculately dressed, haughty and

broad-breasted Mohitmohun. It seemed to her that he was like Mahendra the King,

who had all the good luck on earth. She imagined that the well-dressed, good-looking

young man with his head held high possessed everything and was also worth being

bestowed with everything that one possessed. In her mind the widow would endow

Mohit with all heavenly qualities and make him the God, like a little girl playing with

a doll, thinking it to be a real being.

On some of the evenings she could see Mohits brightly lit room, brimming with the

sound of dancers footsteps and voice of female singers. Those days she would sit up

late, sleepless, staring thirstily at the silhouettes of the dancing figures. Her tormented

heart would, like a caged bird, repeatedly pound upon the ribs in enormous emotion.

Did she in her mind chide and speak ill about her make-belief God for his

extravagance? Not really. As fire entices insects with the illusion of stars, Mohits

bright, music filled chamber overflowing with amusement and wine would attract

Hemshoshi as an oasis of Heaven. Deep at night she would sit awakened, alone,

building up a world with the shadow and light on the window nearby, mingling with it

her own desires and imaginations. She would place her human-doll at the centre of

this world. In the deserted and silent temple of her mind, she would worship him by

offering like incense in the slow fire of her desire all she hadher youth, her

happiness and sorrows, her life in this earth and beyond. She did not know that on the

other side of the bright window, amidst waves of entertainment lay extreme

weariness, filth, terrible hunger and a fire that eats away life. The widow could not see

from distance the game of devastation being played behind the lights by the heartless

cruelty of a sleepless demon with a crooked smile. Hem could have spent her entire

life dreaming at her own window with her imagined heaven and God, but

unfortunately, the God became merciful and the heaven started getting closer to the

earth. When heaven touched upon earth, the heaven crumbled as did the person who

had been building it all these days on her own.

When Mohits lustful eyes fell on this mesmerised girl of the opposite window, when

one day he got an emotion laden, misspelled letter written in nervous trepidation in

response to his many missives sent under the pseudo name Binodchandro, when

thereafter for some eventful days a storm started blowing over many ups and

downs, jubilation, hesitation, suspicion, reverence, hopes and fear, thereafter how the

entire world maddened by pleasure started revolving around the widow and how after

such continuous revolution the world completely vanished like a shadow and how at

last one day all of a sudden, from that revolving world the lady got detached and was

thrown faraway off at great speed, it is not necessary to give a detailed description of

all that.

One day late at night Hemshoshi left her parents, brothers and her home behind and

started off in the same carriage with the holder of the pseudo name Binodchandro.

When the human-God with all its clay, hay and false golden ornaments came and sat

close to her she almost died of embarrassment and repentance.

When the carriage started she fell crying on the feet of Mohit and pleaded, Oh God

please! I beg you to leave me at my home. Mohit hurriedly muzzled her. The

carriage started moving fast.

As a drowning man on the verge of his death momentarily remembers all the incidents

of his life, Hemshoshi recollected in the deep darkness of the carriage that never

would her father sit down to dine without having her in front of him; she remembered,

her youngest brother would love to be fed by her after returning from school; that she

would sit down with her mother in the morning to make betel leaves and in the

evenings her mother would tie her hair. Every little corner of her home and every little

incident started appearing before her in blazing prominence. All the daily chores:

making betel leaves, tying the hair, waving the fan at his father when he was dining,

plucking his grey hair when he would be asleep on a holiday afternoon, bearing with

the mischiefs of her brothers all those appeared to be things of immense satisfaction

and rare pleasure; she failed to understand what else one required in the world to be

happy!

She thought; all girls in the world would be in deep slumber at the moment. How did

she fail to realise the pleasure of a quiet nights peaceful sleep in her own bed, in her

own room? The girls would wake up next day morning, unhesitatingly immerse

themselves in their daily duties; and this sleepless night of the renegade Hemshoshi

where would it dawn; and on such joyless morning when the familiar, soothing and

smiling rays of the sun would fall on their humble household what embarrassment

would be revealed all of a sudden what disgrace and wailing would ensue!

Heart rendering feat of sobbing befell Hem; she prayed repeatedly, The night is yet

to end. My mother, my two brothers have still not risen; you can still drop me back.

But her God would not listen; he continued to take her towards her much sought-after

heaven, accompanied by the clickety-clack band of a second class chariot.

It was not long when God and the heaven parted ways with her in another rickety

second class carriage the lady remained immersed in neck-deep muck.

Third episode

Only one the many incidents from Mohitmohuns past has been narrated above,

otherwise the piece would become repetitive.

Neither is it necessary to refer to such old incidents at this juncture. Today, it is

doubtful whether anyone exists in the world who remembers the name Binodchandro.

These days, Mohit observes all the prescribed rites of purity, worships God and is

always into discussion of the scriptures. He even makes his young sons

practiseYoga and vehemently guards the women folk deep inside his house from the

sun, the moon and the air. But since once upon a time he had wronged many women

today he makes sure that he levies the strictest of penalties on women for any social

crime committed by them.

A day or two after having sentenced Khiroda to death the gourmet Mohit went to the

garden adjoining the prison to collect his favourite vegetables. He felt curious to know

whether Khiroda was repenting for all the crimes she had committed in her life as a

fallen woman. He entered the prison chamber.

From a distance he could hear the noise of people quarrelling. Entering the room he

found Khiroda engaged in a verbal duel with the prison guard. Mohit was amused; he

felt, such is the habit of women! They would not let up on quarrelling even when

death is near. Perhaps, when they reach hell they quarrel with the guards there.

Mohit thought, it would be proper to invoke repentance in her even at this stage by

appropriately chiding and advising. As soon as he had approached Khiroda with the

aforesaid noble purpose, Khiroda implored with folded hands, I appeal on your

honour! Please tell him to return my ring.

Asking questions he came to know that a ring was kept concealed in Khirodas hair

as luck would have it, the prison guard confiscated it on noticing.

Mohit was again amused. A day or two to go before she would be hanged, yet she

cant forget her ring; ornaments are all to these womenfolk!

He called the guard, Where is the ring, let me see it the guard handed over the ring

to him.

Mohit was jolted, as if he had unexpectedly come to hold a piece of burning charcoal.

On one side of the ring in ivory curving was implanted a very small oil painted

portrait of a young man sporting beard and moustache, and on the other side was

inscribed in gold Binodchandra.

Mohit raised his eyes from the ring and looked intently on Khirodas face. He

remembered another tender, shy and nervous face with tears overflowing, which he

had seen twenty-four years back. This face had similarity with that one.

Mohit looked on the golden ring again and then when he gradually raised his eyes, the

fallen woman standing in front of him emerged like a golden idol resplendent in the

glow of the small golden ring.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Maestro in Absentia EnglishDokument3 SeitenMaestro in Absentia EnglishJff ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Silence, A Fable by E.A. PoeDokument3 SeitenSilence, A Fable by E.A. PoeMelisa GómezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 6 PoetryDokument19 SeitenModule 6 PoetryJale BieNoch keine Bewertungen

- American RegimeDokument17 SeitenAmerican RegimeReanne Ramirez MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- HUM 002: 21 Century Literature From The Philippines To The WorldDokument11 SeitenHUM 002: 21 Century Literature From The Philippines To The Worldvency amandoronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loquinario-Esp History TimelineDokument2 SeitenLoquinario-Esp History TimelineApril Joyce LocquinarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESP in The PhilippinesDokument2 SeitenESP in The PhilippinesGlennmelove100% (1)

- Child of Sorrow-MikanDokument8 SeitenChild of Sorrow-MikanMikan CacliniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Post Colonial Criticism in Santos' Scent of Apples.Dokument1 SeitePost Colonial Criticism in Santos' Scent of Apples.Julie Ann Longoria BelaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan Indiscover Literature As A Means of Understanding The Human Being and The Forces He/she Has To Contend With.Dokument4 SeitenLesson Plan Indiscover Literature As A Means of Understanding The Human Being and The Forces He/she Has To Contend With.Cristine Shayne BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rolando A. Carbonell: You AloneDokument3 SeitenRolando A. Carbonell: You AloneQueenie CaraleNoch keine Bewertungen

- AmbushDokument1 SeiteAmbushnestor donesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lyster Duzar YOUTHDokument15 SeitenLyster Duzar YOUTHICT AKONoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan P.PinedaDokument7 SeitenLesson Plan P.PinedaMarvinbautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parables of The Ancient PhilosophersDokument8 SeitenParables of The Ancient PhilosophersChristine Joy BaquirNoch keine Bewertungen

- BE Lesson Plan Grade 9 DLL 6-20Dokument1 SeiteBE Lesson Plan Grade 9 DLL 6-20Portia TeradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cruel Summer (Defamiliarization of Nick Joaquin's Summer's Solstice)Dokument4 SeitenCruel Summer (Defamiliarization of Nick Joaquin's Summer's Solstice)Ruben TabalinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RitualDokument20 SeitenRitualVia Roderos75% (4)

- FLIT 3-Survey in The Philippine Literature in EnglishDokument4 SeitenFLIT 3-Survey in The Philippine Literature in EnglishMarlon KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forsaken HouseDokument6 SeitenForsaken HouseCarolina BenaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acfrogascy-Br Cjcnsy4uqdmfveujkrh4kbg7cwjdhtznrmaz0fqgqbaxq-Jdgww6 Kyxhrrh8adqtcam 5oglf6caow1fqxwthgvs9hzxcaz Uflrne9byvwu-Vlxj8ybc j0d8nvszl Ckb6tDokument18 SeitenAcfrogascy-Br Cjcnsy4uqdmfveujkrh4kbg7cwjdhtznrmaz0fqgqbaxq-Jdgww6 Kyxhrrh8adqtcam 5oglf6caow1fqxwthgvs9hzxcaz Uflrne9byvwu-Vlxj8ybc j0d8nvszl Ckb6tJohn Carl AparicioNoch keine Bewertungen

- By: Rafael Zulueta Da Costa (1940) : Like The MolaveDokument1 SeiteBy: Rafael Zulueta Da Costa (1940) : Like The MolaveMae Mallapre100% (2)

- The Epic of BidasariDokument7 SeitenThe Epic of BidasariDave Michel Dela Cruz50% (2)

- Cesar Ruiz AquinoDokument1 SeiteCesar Ruiz AquinoJay-Ann SarigumbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Works of Spanish Religious About The Philippines (1593-1800)Dokument3 SeitenWorks of Spanish Religious About The Philippines (1593-1800)Divine CardejonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 2 Poem: Valediction Sa Hillcrest Let'S Warm Up!Dokument7 SeitenLesson 2 Poem: Valediction Sa Hillcrest Let'S Warm Up!Angielyn Montibon Jesus0% (1)

- Literature Under The Us ColonialismDokument2 SeitenLiterature Under The Us ColonialismLeila PanganibanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1-Grammatical Metalanguage and Sentential TerminologyDokument40 Seiten1-Grammatical Metalanguage and Sentential TerminologyJan Michael de Asis100% (2)

- Burmese LiteratureDokument3 SeitenBurmese LiteratureSef Getizo Cado0% (1)

- Orca Share Media1496398782229Dokument191 SeitenOrca Share Media1496398782229FghhNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENTERTAINMENT SPEECH in ENGLISHDokument1 SeiteENTERTAINMENT SPEECH in ENGLISHElaizah Niña MeloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hand Out (Like The Molave)Dokument2 SeitenHand Out (Like The Molave)Farrah Mie Felias-Ofilanda100% (1)

- Review of Related Literature A. Theoretical Framework 1. The Nature of PronunciationDokument25 SeitenReview of Related Literature A. Theoretical Framework 1. The Nature of PronunciationMike Nurmalia SariNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5fan - Ru - Expressive Means and Stylistics DevicesDokument6 Seiten5fan - Ru - Expressive Means and Stylistics DevicesJulia BilichukNoch keine Bewertungen

- CW Report Lesson 3Dokument2 SeitenCW Report Lesson 3Eugene BalindanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing MemorandaDokument18 SeitenWriting MemorandaBianca PetalioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Guide - Urbana at FelisaDokument2 SeitenLesson Guide - Urbana at FelisaMARY ANN ILLANA0% (1)

- Myths Derived From Scripture PDFDokument4 SeitenMyths Derived From Scripture PDFJang Magbanua100% (1)

- The Bewildered ArabDokument2 SeitenThe Bewildered ArabVILLA ROSE DELFINNoch keine Bewertungen

- LESSON 3-On-National-Literature-and-Social-DimensionDokument19 SeitenLESSON 3-On-National-Literature-and-Social-DimensionJhedzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alberto K. Tiempo's Novel AnalysisDokument13 SeitenAlberto K. Tiempo's Novel AnalysisEstrella Janirol Humoc Piccio100% (2)

- Literary TextsDokument2 SeitenLiterary TextsMico Roces100% (1)

- Spanish Colonial Period (1565-1872) : Mary Ann P. AletinDokument15 SeitenSpanish Colonial Period (1565-1872) : Mary Ann P. AletinKris Jan CaunticNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 7 1st Bread of SaltDokument5 SeitenGrade 7 1st Bread of SaltJonalyn AcobNoch keine Bewertungen

- Region 4Dokument5 SeitenRegion 4Krisjoii21100% (2)

- 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldDokument23 Seiten21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldHarold Ambuyoc100% (1)

- The Emergence Period FDokument64 SeitenThe Emergence Period FJimbo Manalastas67% (3)

- Checklist For Teaching Strategies Responsive To Learners' Special NeedsDokument3 SeitenChecklist For Teaching Strategies Responsive To Learners' Special NeedsREBECCA STA ANANoch keine Bewertungen

- TuwaangDokument18 SeitenTuwaangJames JamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Greatest Heroes Before The Trojan WarDokument3 SeitenThe Greatest Heroes Before The Trojan WarSim BelsondraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Text Talk NovelDokument1 SeiteText Talk NovelAbegail CachuelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On The Emergent PeriodDokument2 SeitenNotes On The Emergent PeriodReinopeter Koykoy Dagpin LagascaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test QuestionsDokument13 SeitenTest Questionsmaricel ubaldoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Works of Bicolano, Eastern Visayas, Ilonggo, and MuslimDokument6 SeitenLiterary Works of Bicolano, Eastern Visayas, Ilonggo, and MuslimDark CrisisNoch keine Bewertungen

- RizalDokument9 SeitenRizalMYLA ROSE A. ALEJANDRONoch keine Bewertungen

- ReactionDokument10 SeitenReactionMary Mae Alquizar100% (2)

- Rizalfinal 3Dokument6 SeitenRizalfinal 3Lei LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filipino PoetsDokument22 SeitenFilipino PoetsMaxine Gail CeleridadNoch keine Bewertungen

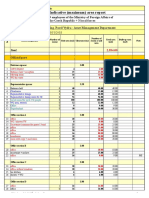

- Estimate Isolation FacilityDokument2 SeitenEstimate Isolation FacilityAxle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Felipe MDokument2 SeitenFelipe MAxle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our Lady of The Pillar Parish Church, Commonly Known AsDokument28 SeitenOur Lady of The Pillar Parish Church, Commonly Known AsAxle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- McLaren 720s Spider Order SummaryDokument4 SeitenMcLaren 720s Spider Order SummaryAxle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multistoreyed Building 2Dokument40 SeitenMultistoreyed Building 2V.m. Rajan100% (2)

- NAW 2018 Invitation Letter To Tahanang Carmela D'AmoreDokument2 SeitenNAW 2018 Invitation Letter To Tahanang Carmela D'AmoreAxle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- EN - Orientation Display AreasDokument3 SeitenEN - Orientation Display AreasAxle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Studying Complex Tourism Systems: A Novel Approach Based On Networks Derived From A Time SeriesDokument14 SeitenStudying Complex Tourism Systems: A Novel Approach Based On Networks Derived From A Time SeriesAxle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gen Meeting 29 Nov 2018Dokument2 SeitenGen Meeting 29 Nov 2018Axle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dolmens, Menhirs, Cromlechs: "The Magical Stones"Dokument1 SeiteDolmens, Menhirs, Cromlechs: "The Magical Stones"Axle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 3 Region 4 WritersDokument15 SeitenGroup 3 Region 4 WritersMicah Faith GuillenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3 Study GuideDokument4 SeitenLesson 3 Study GuideKyla Renz de LeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of The Philippine Literature-1Dokument56 SeitenHistory of The Philippine Literature-1Ethan MacalisangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature Under JapaneseDokument14 SeitenPhilippine Literature Under JapaneseJodesa SorollaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ako Ang DaigdigDokument4 SeitenAko Ang DaigdigRachel NicoleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phil. Lit 6Dokument9 SeitenPhil. Lit 6J-zeil Oliamot PelayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Am The Universe by Alejandro AbadillaDokument2 SeitenI Am The Universe by Alejandro AbadillaDivine Grace Merina (Dibs)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature Under US Colonial Rule: The Period of Apprenticeship Virginia R. MorenoDokument15 SeitenPhilippine Literature Under US Colonial Rule: The Period of Apprenticeship Virginia R. MorenoliliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature During American Colonial PeriodDokument14 SeitenPhilippine Literature During American Colonial PeriodJK PedrosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Ako Ang Daigdig" by Alejandro Abadilla: An AnalysisDokument3 Seiten"Ako Ang Daigdig" by Alejandro Abadilla: An AnalysisJog YapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literary Periods CompleteDokument29 SeitenPhilippine Literary Periods CompleteHorne100% (2)

- Alejandro G. Abadilla: NovelsDokument6 SeitenAlejandro G. Abadilla: NovelsFelix SalongaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine LitDokument15 SeitenPhilippine LitAxle Ross BartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 AmericanDokument21 Seiten5 AmericanAnghelica EuniceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alejandro GDokument9 SeitenAlejandro GWalang PoreberNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature Under The Republic PPT 1Dokument19 SeitenPhilippine Literature Under The Republic PPT 1Princess CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- FINAL CORE 5 - 21st Century From The Phil. and WorldDokument60 SeitenFINAL CORE 5 - 21st Century From The Phil. and WorldJelamie ValenciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21st CenturyDokument15 Seiten21st CenturyFranchell Mads100% (1)

- Bba 104Dokument30 SeitenBba 104Anonymous Vng49z7hNoch keine Bewertungen

- E BookDokument51 SeitenE BookSherlyn DelacruzNoch keine Bewertungen