Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

EDUC5429 Essay

Hochgeladen von

Ruiqi.ng0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

193 Ansichten11 SeitenDiscuss how your understanding of the impact of culture, cultural identity and linguistic background on the education of students from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds will inform your practices as a teacher or school psychologist.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenDiscuss how your understanding of the impact of culture, cultural identity and linguistic background on the education of students from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds will inform your practices as a teacher or school psychologist.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

193 Ansichten11 SeitenEDUC5429 Essay

Hochgeladen von

Ruiqi.ngDiscuss how your understanding of the impact of culture, cultural identity and linguistic background on the education of students from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds will inform your practices as a teacher or school psychologist.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 11

THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA

EDUC5429: ABORIGINAL EDUCATION

ASSIGNMENT 2: ESSAY

Unit Coordinator: Clint Bracknell

Student Name: Rui Qi Ng

Student Number: 20751156

Word count: 1996

Discuss how your understanding of the impact of culture, cultural identity and linguistic

background on the education of students from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

backgrounds will inform your practices as a teacher or school psychologist.

A growing number of researches have reported poor educational outcomes in Indigenous

students (De Plevitz, 2007). These studies have raised many factors that affect the

achievement of Indigenous students, including the lack of parental commitment and high

rates of absenteeism (De Plevitz, 2007). Nonetheless, poor educational outcomes cannot be

blamed on students who are more often the victims of cultural inequality (De Plevitz, 2007).

Teachers must understand that culture, cultural identity and the linguistic background of

Indigenous students may be barriers to their learning experience in western education. The

understanding of these three factors gives teachers better understanding of Indigenous

students.

Failure to succeed in schools for Indigenous students is largely attributed to the lack of

Indigenous culture knowledge and perspective in school curriculum and among teachers who

are predominantly non-Indigenous (Kanu, 2005). Children from different cultural background

often interpret concepts differently from the standard view. This is especially true for the

teaching of science (Snively & Corsiglia, 2000). Consequently, students bring a broad range

of ideas, beliefs, values and experiences into the classroom. Constructivism suggested that

concepts of knowledge and beliefs are inseparable (Snively & Corsiglia, 2000). Therefore, it

is not that Indigenous students fail to comprehend what is taught. Instead, it may simply be

that the concepts are not credible or relevant to the student (Snively & Corsiglia, 2000). As a

result, it is always important to understand that cultural differences in the classroom is an

important factor to learning and also that underachievement of students is not a result of

deficit in the culture or the person (McKinley, 2005).

Studies found that educational success for Indigenous students is about high achievement in

western education while retaining their Indigenous identity and cultural connection (Milroy,

2011). As a result, to increase educational achievement including attendance, retention and

completion of Indigenous students, many studies have suggested the inclusion of

Indigenous culture perspective across the school curriculum (Kanu, 2005; Northern Territory

Government, 2010). It is essential to engage with Indigenous Australian perspective to

increase understanding and mutual respect between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students

(Northern Territory Government, 2010). Additionally, including Indigenous perspectives by

teaching culturally appropriate contexts makes the learning materials more relevant to

Indigenous students and enables them to develop their sense of identity and pride in their

culture (McKinley, 2005; Northern Territory Government, 2010).

The Department of Education (2010) suggested that Aboriginal perspectives could be taught

in one of the three ways: as an Aboriginal studies subject; as a unit of study or topic which is

part of another subject; and/or integrated into units of work which is taught in a wide range of

learning areas throughout all years of schooling. Materials used to incorporate Aboriginal

perspectives into classrooms should be from a primary resource that is based on the

community histories, people and places; acknowledges the local Aboriginal Elders and their

culture (Harrison, 2011). Furthermore, it is important to use current and contemporary

resources as old materials may contain stereotypes which are incorrect description of

Aboriginal people (Harrison, 2011). Therefore, the understanding of cultural differences

between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students should encourage teachers to incorporate

Aboriginal perspective texts in the classrooms.

Teachers should also understand the cultural obligations that Indigenous students may face.

Attendance of school may be affected as a result of funerals which Indigenous students are

obliged to attend (De Plevitz, 2007). Along with higher rates of metal and physical health

problems, indigenous adults have shorter life expectancy than non-Indigenous people (De

Plevitz, 2007). Hence, death may occur in not only the grandparents generation but also

parents, aunties and uncles. As funerals do not take place until all relatives have arrived,

Indigenous students may be away from school for a considerable amount of time (De Plevitz,

2007). In times as such, teachers should ensure that students would not miss out on any

learning.

Understanding the cultural identity of Indigenous students is also important for encouraging

success in learning in the classroom. Cultural identity is formed by the complex configuration

of an individuals awareness of their culture and recognition of the social group to which they

belongs in (Lee, 2002). An identity could be either ascribed, where it is assigned to you, or

achieved which is a developed through choice (Forrest, 1998). Cultural identity is typically

ascribed to one (Forrest, 1998). Aboriginality is the identity that makes a person an

Aboriginal which is often based not only on biological characteristics but also social

characteristics (Forrest, 1998; Warburton & Chambers, 2007).

Regardless of living in closely knit communities in rural areas or in the urban city, a wide

range of literature suggested that Aboriginal people develop a strong sense of identity based

on kinship ties (Yamanouchi, 2010; Groome, 1995; Forrest, 1998). One has to be accepted

and be spiritually connected to the community; and maintain traditional ties in order to have

an Aboriginal identity (Yeo, 2003). Yamanouchi (2010) suggested that family identification

where people establish who and where they are from and display understanding on what

being Aboriginal is about is primal to being accepted as Aboriginal in south-western

Sydney. Unlike most Australian norms, extended family makes up the close circle of

Aboriginal family who provides kinship roles (Groome, 1995; Warburton & Chambers,

2007). Family is the most significant aspect in the development of identity of most young

Aboriginal people (Groome, 1995). It is through families that Aboriginal people receive their

formative training to understand accepted behaviours, values and beliefs (Groome, 1995).

Majority of Aboriginal families are deeply concerned to see their children grow up with a

strong sense of Aboriginality (Groome, 1995).

Indigenous people believe that a child needs to be aware and understand the value placed on

kin and attachment to a distinct home territory (Groome, 1995). Children are expected to

become responsible individuals who balance independence and resourcefulness with skills of

group and family membership. These values are taught and modelled through ties and

allegiances within the extended family (Groome, 1995). As a result, in comparison to Anglo-

Australian parents, Aboriginal parents tend to intervene less in the lives of their children and

young people so as to allow them to experience relatively high levels of freedom and

independence (Groome, 1995). Young Aboriginal people are of often reminded of the

importance of their sense of place and relationship of the Aboriginal people to the land

through stories, histories and jokes told by relatives (Groome, 1995). A sense of belonging is

therefore developed as a consequence of kinship bonds and communal life (Yeo, 2003).

Spirituality is also the foundation of the Aboriginal identity. They believe that ancestral

creative beings travelled across the continent during the beginning of time and established

land boundaries between different Aboriginal groups and sacred sites (Yeo, 2003).

Consequently, Aboriginal people carry out rituals at sacred sites and perform religious

ceremonies to feel bound to their land (Yeo, 2003). As Aboriginal people hold deep spiritual

links with their lands, they feel that they are an integral part of the physical environment

(Yeo, 2003).

As a result of the difference in cultural identity in comparison to Anglo-Australian students,

Aboriginal students may experience challenges surrounding the expression of cultural

identity in their classroom (Ortiz, 2000). Some students may feel incompetent as a result of

having different cultural identity (Ortiz, 2000). Nonetheless, it is important for children to be

aware and proud of their Aboriginal identity. Teachers may develop intercultural competence

using cooperative and collaborative methods. These interactions with other students allow

students to express their cultural identity openly (Ortiz, 2000). Alternatively, teachers may

also include Aboriginal perspective into the classroom for students to create a risk-free

learning environment where students could still maintain their identity (McKinley, 2005).

Indigenous students linguistic background is also a factor that affects their learning in

school. The home language of Indigenous Australians constitutes three main linguistic

varieties: Indigenous language, creoles and Aboriginal English (Malcolm, 2003). In

Australia, Creoles are created when Indigenous speakers are confronted with English by an

invading group (Malcolm, 2003). These people attempt to use this language without prior

preparation (Malcolm, 2003). Two distinct creoles are generally recognised in Australia. One

of which is spoken in Torres Strait Islands and the other on the mainland arising

independently in a number of forcibly mixed communities (Butcher, 2008). Like any other

language, Creoles are complex, rule-governed codes with an extensive vocabulary (Butcher,

2008). Hence it is important to recognise that Creoles are languages in their own rights

(Butcher, 2008). Aboriginal English is a dialect of English that is spoken by Indigenous

people throughout Australia (Sharifian, 2001). It is different from standard Australian English

(SAE) phonologically, syntactically and pragmatically (Sharifian, 2001; Purdie, Oliver,

Collard & Rochecouste, 2002).

According to Malcolm (2003), approximately 12.1% of Indigenous students use Indigenous

language as their home language while most of the remaining 79.8% use a variety of English

language which has been maintained within the Indigenous community that differs from

Standard Australian English (SAE). A continuum of variation exists between Creole or

minority English dialect and SAE (Siegal, 2000; Purdie et al., 2002). This forms a major

disadvantage to speakers of creoles or minority dialects in formal education system as the

language of education is a standard variety which they do not speak (Siegal, 2000). More

often, rather than viewing Creole or minority dialects as a deviant form of the standard

education language, some communities see them as an illegitimate language (Siegal, 2000).

Many Australian Aboriginal children speaking Aboriginal English as their primary means of

communication are expected to learn SAE as their second dialect in schools (Sharifian,

2001). As a result of their linguistic background, students that speak Creole or minority

dialects at home may experience some educational inequalities and struggles in school. The

ignorance and negative attitudes of teachers may result in linguistic prejudice towards

Indigenous students who lack understanding of the SAE that is being used in school (Siegal,

2000). The ignorance of teachers may lead to teachers mistaking language problems of

Creole- or dialect-speaking students for stupidity which may further lead to stereotyping

(Siegal, 2000). Such prejudice consequently leads to teachers lowering their expectations of

students and leading to lower students performance and thus reinforcing stereotype. This is

closely related to the next struggle that Indigenous students may face. Many Creole or

Aboriginal English speaking students form negative attitudes about themselves as they do not

regard their form of language as a legitimate language (Siegal, 2000). Rather, they think of it

as a broken form of the standard language. Consequently, these students may experience

low self-esteem and low academic self-concept. When students are not allowed to use their

home language in schools, they repress self-expression because of the need to use an

unfamiliar form of language (Siegal, 2000).

Through the understanding of Indigenous Australian students linguistic background,

teaching practices could be adjusted to better suit the students learning needs and prevent

students from being disinterested in education. Teachers should understand the nature of

creoles and minority dialects by being more knowledgeable about the language background

of their students (Siegal, 2000). Without reducing students self-esteem, teachers should find

ways to assist students to become aware of the language difference. Siegal (2000) also

suggested that students language varieties should be legitimised by bringing them into the

classroom. This could be done by using aspects of Creole or minority dialect speakers

culture; allowing and encouraging students to write in varieties; and examining linguistic and

pragmatic differences between Creoles or minority dialects and SAE (Siegal, 2000). The

above strategies could be used in classrooms to broaden Indigenous students linguistic

repertoire to enable them to code switch from Aboriginal English to SAE.

It is therefore clear that the understanding of students is an essential factor for creating a risk-

free learning environment. This is especially true for Indigenous Australian students whose

culture, cultural identity and linguistic background may have an impact on their learning in

western schools. In addressing such issues, teachers are encouraged to understand the culture,

include Indigenous perspective resources and to acknowledge the different types of dialects

spoken at home.

Reference

Butcher, A. (2008). Linguistic aspects of Australian Aboriginal English. Clinical Linguistics

and Phonetics, 22(8), 625-642. Retrieved from EBSCO Host.

De Plevitz, L. (2007). Systemic racism: the hidden barrier to educational success for

Indigenous school students. Australian Journal of Education, 51(1), 54-71. Retrieved from

ProQuest.

Department of Education. (2010). Aboriginal perspectives across the curriculum. Retrieved

from

http://www.det.wa.edu.au/aboriginaleducation/apac/detcms/navigation/apac/?oid=MultiPartA

rticle-id-9193776

Forrest, S. (1998). Thats my mob: Aboriginal identity. Perspectives on Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander education, 96-105.

Groome, H. Towards improved understandings of Aboriginal young people. Youth Studies

Australia, 14(4), 17-21. Retrieved from EBSCO Host.

Harrison, N. (2011). Teaching and learning in Aboriginal education. South Melbourne, Vic:

Oxford University Press.

Kanu, Y. (2005). Teachers perception of the integration of Aboriginal culture into the high

school curriculum. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 51(1), 50-68. Retrieved

from ProQuest.

Lee, J.S. (2010). The Korean language in America: The role of cultural identity in heritage

language learning. Language, Culture and Curriculum,15(2), 117-133. Retrieved from Taylor

and Francis.

Malcolm, I.G. (2003). English language and literacy development and home language

support: Connections and directions in working with Indigenous students. TESOL in Context,

13(1), 5-18. Retrieved from lms.uwa.edu.au

McKinley, E. (2005). Locating the global: Culture, language and science education for

Indigenous students. International Journal of Science Education, 27(2), 227-241. Retrieved

from Taylor and Francis.

Milroy, J. (2011). Incorporating and understanding different ways of knowing in the

education of Indigenous students. Paper presented at the ACER Research Conference 2011.

Retrieved from http://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference/RC2011/8august/13/

Northern Territory Government. Department of Education and Training (2010). Embedding

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Perspectives in Schools. Retrieved from

http://www.education.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/15228/EmbeddingAboriginalPer

spectivesInSchools.pdf

Ortiz, A.M. (2000). Expressing cultural identity in the learning community: Opportunities

and challenges. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2000(82), 67-79. Retrieved from

Wiley Online Library.

Purdie, N., Oliver, R., Collard, G., & Rochecouste, J. (2002). Attitudes of primary school

Australian children to their linguistic codes. Journal of Language and Social Psychology,

21(4), 410-421. Retrieved from SAGE Publications.

Sharifian, F. (2001). Schema-based processing in Australian speakers of Aboriginal English.

Language and Intercultural Communication, 1(2), 120-134. Retrieved from Taylor and

Francis.

Siegel, J. (2000). Creoles and minority dialects in education: An overview. Journal of

Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 20(6), 508-531. Retrieved from Taylor and

Francis.

Snively, G., & Corsiglia, J. (2000). Discovering Indigenous science: Implications for science

education. Science Education, 85(1), 6-34. Retrieved from Wiley Online Library.

Warburton, J., & Chambers, B. (2007). Older Indigenous Australians: Their integral role in

culture and community. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 26(1), 3-7. Retrieved from Wiley

Online Library.

Yamanouchi, Y. (2010). Kinship, organisations and wannabes: Aboriginal identity

negotiation in South-west Sydney. Oceania, 80(2), 216-228. Retrieved from ProQuest.

Yeo, S.S. (2003). Bonding and attachment of Australian Aboriginal children. Child Abuse

Review, 12(), 292-304. Retrieved from Wiley Online Library.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Aboriginal Ed. Essay - Moira McCallum FinalDokument8 SeitenAboriginal Ed. Essay - Moira McCallum Finalmmccallum88Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal Education Assignment 2Dokument10 SeitenAboriginal Education Assignment 2bhavneetpruthyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal EssayDokument4 SeitenAboriginal Essayapi-471893759Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 2Dokument8 SeitenAssignment 2api-360867615Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rachael-Lyn Anderson EDED11458 LetterDokument14 SeitenRachael-Lyn Anderson EDED11458 LetterRachael-Lyn AndersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment 2Dokument6 SeitenAssessment 2api-464657410Noch keine Bewertungen

- Eo IGarciaDokument19 SeitenEo IGarciaLily100% (1)

- Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education: Assessment Two - EssayDokument6 SeitenTeaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education: Assessment Two - Essayapi-465726569Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal Assignment 20Dokument5 SeitenAboriginal Assignment 20api-369717940Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indigenous EducationDokument9 SeitenIndigenous Educationapi-358031609Noch keine Bewertungen

- Professional ReflectionDokument2 SeitenProfessional Reflectionapi-326401258Noch keine Bewertungen

- Diversity EssayDokument7 SeitenDiversity Essayapi-460524150Noch keine Bewertungen

- EssayDokument6 SeitenEssayapi-532442874Noch keine Bewertungen

- Essay: Tiarna Said - Student ID # 110186242Dokument5 SeitenEssay: Tiarna Said - Student ID # 110186242api-529553295Noch keine Bewertungen

- RTL Assignment 2Dokument14 SeitenRTL Assignment 2api-408345354Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?Dokument6 SeitenWhat Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?api-525572712Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal Education EssayDokument7 SeitenAboriginal Education Essayappy greg100% (2)

- Assignment 3Dokument7 SeitenAssignment 3api-298157181Noch keine Bewertungen

- Critically Reflective EssayDokument9 SeitenCritically Reflective Essayapi-478766515Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal EssayDokument5 SeitenAboriginal Essayapi-428484559Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assignment 1Dokument8 SeitenAboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assignment 1api-332411347Noch keine Bewertungen

- Keer Zhang 102085 A2 EssayDokument13 SeitenKeer Zhang 102085 A2 Essayapi-460568887100% (1)

- Kristy Snella3Dokument9 SeitenKristy Snella3api-248878022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Acrp Essay - Rachel Jolly 19665131Dokument9 SeitenAcrp Essay - Rachel Jolly 19665131api-553761934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Acrp EssayDokument10 SeitenAcrp Essayapi-357686594Noch keine Bewertungen

- Developing Cultural Awareness in Foreign Language Teaching PDFDokument5 SeitenDeveloping Cultural Awareness in Foreign Language Teaching PDFDulce Itzel VelazquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acrp Essay Final Brooke Grech 18893641Dokument14 SeitenAcrp Essay Final Brooke Grech 18893641api-466676956Noch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence 2Dokument2 SeitenEvidence 2api-527267271Noch keine Bewertungen

- Brand New AssignmentDokument7 SeitenBrand New Assignmentapi-366587339Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?Dokument4 SeitenWhat Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?api-525572712Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assessment 1Dokument9 SeitenAboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assessment 1api-321128505Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 2 Aboriginal Education Isabel SarreDokument6 SeitenAssignment 2 Aboriginal Education Isabel Sarreapi-465723124Noch keine Bewertungen

- Acrp Assessment 2 EssayDokument9 SeitenAcrp Assessment 2 Essayapi-533984328Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Essay Ethan Sais 17974628Dokument8 SeitenAboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Essay Ethan Sais 17974628api-357549157Noch keine Bewertungen

- Educ2420 Final EssayDokument3 SeitenEduc2420 Final Essayapi-479176506Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assessment 1 - Option 2Dokument12 SeitenAboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assessment 1 - Option 2api-321112414Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2h2018assessment1option1Dokument9 Seiten2h2018assessment1option1api-317744099Noch keine Bewertungen

- Self-Esteem and Cultural Identity in Aboriginal Language Immersion KindergartenersDokument17 SeitenSelf-Esteem and Cultural Identity in Aboriginal Language Immersion KindergartenersTerim ErdemlierNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dealing With Difference: Building Culturally Responsive ClassroomsDokument16 SeitenDealing With Difference: Building Culturally Responsive ClassroomsKim ThuyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABORIGINAL and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies EssayDokument9 SeitenABORIGINAL and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Essayapi-408471566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Catherine Spear Assignment 2Dokument7 SeitenCatherine Spear Assignment 2api-471129422Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indigenous StudentsDokument10 SeitenIndigenous Studentsapi-463933980Noch keine Bewertungen

- Test 2Dokument24 SeitenTest 2jaysonfredmarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal Education Essay2 FinalDokument5 SeitenAboriginal Education Essay2 Finalapi-525722144Noch keine Bewertungen

- Abs2001 - Essay FinalDokument6 SeitenAbs2001 - Essay FinalMy KhanhNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2h Reflection MurgoloDokument6 Seiten2h Reflection Murgoloapi-368682595Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ab 3Dokument10 SeitenAb 3api-356862575Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 2Dokument7 SeitenAssignment 2api-480489007Noch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study NewDokument4 SeitenCase Study Newapi-466313157Noch keine Bewertungen

- Alisha Rasmussen - 19059378 - Assessment One - Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive PedagogyDokument15 SeitenAlisha Rasmussen - 19059378 - Assessment One - Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogyapi-466919284Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal EssayDokument6 SeitenAboriginal Essayapi-427522957Noch keine Bewertungen

- EssayDokument7 SeitenEssayapi-413124479Noch keine Bewertungen

- Is Ass 1aDokument4 SeitenIs Ass 1aapi-329377710Noch keine Bewertungen

- Multicultural Education APA ExampleDokument8 SeitenMulticultural Education APA ExampleGena SaldanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 2Dokument7 SeitenAssignment 2api-350319898Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal Studies Assignment 2Dokument5 SeitenAboriginal Studies Assignment 2api-465725385Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 1: Aboriginal Education Critically Reflective Essay Option 1Dokument13 SeitenAssignment 1: Aboriginal Education Critically Reflective Essay Option 1api-408516682Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 3Dokument5 SeitenAssignment 3api-456358200Noch keine Bewertungen

- Culture 3 (Definition)Dokument30 SeitenCulture 3 (Definition)Javed IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diversity in American Schools and Current Research Issues in Educational LeadershipVon EverandDiversity in American Schools and Current Research Issues in Educational LeadershipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science Integrated Program - 5EDokument10 SeitenScience Integrated Program - 5ERuiqi.ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summative Assessment - ChecklistDokument1 SeiteSummative Assessment - ChecklistRuiqi.ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- 29 May 2013 AppendixDokument1 Seite29 May 2013 AppendixRuiqi.ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- 28 August (Mathematics - Upper Group Additional 1)Dokument1 Seite28 August (Mathematics - Upper Group Additional 1)Ruiqi.ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Lesson Plan Pro FormaDokument2 SeitenSample Lesson Plan Pro FormaRuiqi.ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Migration To Australia Unit PlanDokument4 SeitenMigration To Australia Unit PlanRuiqi.ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- 28 August (Mathematics - Lower Group)Dokument1 Seite28 August (Mathematics - Lower Group)Ruiqi.ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resource Collection Write UpDokument1 SeiteResource Collection Write UpRuiqi.ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creating A Positive Learning Environment For Indigenous StudentsDokument46 SeitenCreating A Positive Learning Environment For Indigenous Studentsapi-327273672Noch keine Bewertungen

- Spoke SongDokument21 SeitenSpoke SongLilibeth EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Get Set Skills Employment Training Model For PracticeDokument50 SeitenGet Set Skills Employment Training Model For PracticeIsabelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Issue1 All PapersDokument63 SeitenIssue1 All PapersVictoria ChapperónNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attitudes To Australian EnglishDokument1 SeiteAttitudes To Australian EnglishloveethescriptNoch keine Bewertungen

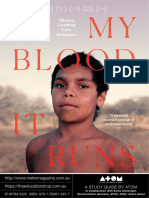

- ATOM Study Guide - in My Blood It RunsDokument22 SeitenATOM Study Guide - in My Blood It RunsDaisy Lapetite100% (1)

- Kaleb Malanin's notes on varieties of EnglishDokument8 SeitenKaleb Malanin's notes on varieties of English9993huwegNoch keine Bewertungen

- Esl FundamentalDokument40 SeitenEsl FundamentalTaufiq Wibawa100% (2)