Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

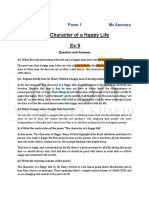

09 Feminism

Hochgeladen von

Ariella Araujo Guarani-Kaiowá Kadiwéu Yanomami0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

56 Ansichten21 SeitenThe review draws attention to a new focus in feminist writing on the international / global. The shift of feminist interest from International Relations to globalisation does not, as we will see, necessarily mean an equal shift from the critique of domination or dominant discourses.

Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThe review draws attention to a new focus in feminist writing on the international / global. The shift of feminist interest from International Relations to globalisation does not, as we will see, necessarily mean an equal shift from the critique of domination or dominant discourses.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

56 Ansichten21 Seiten09 Feminism

Hochgeladen von

Ariella Araujo Guarani-Kaiowá Kadiwéu YanomamiThe review draws attention to a new focus in feminist writing on the international / global. The shift of feminist interest from International Relations to globalisation does not, as we will see, necessarily mean an equal shift from the critique of domination or dominant discourses.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 21

93

8 - Feminism, Globalisation, Internationalism:

The State of Play and the Direction of the Movement

(2005)

[Source: Waterman, Peter. 2005. Feminism, Globalisation, Internationalism: The State of Play

and the Direction of the Movement, www.choike.org/ documentos/feminism_ global.pdf]

Peggy Antrobus, The Global Womens Movement: Origins, Issues and Strategies. London:

Zed Books, 2004, 204 pp. Source: http://www.zedbooks.co.uk/book.asp?bookdetail=3553

94

Mrinalini Sinha, Donna Guy and Angela Woollacott (eds.), Feminisms and

Internationalism, Blackwell, Oxford and Malden (MA). 1999. 264 pp.

'Globalisation and Gender', Signs, Vol. 26, No. 4, Summer 2001. Special Issue.

Editors: Amrita Basu, Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, Liisa Malkki. Pp. 943-1314.

Peggy Antrobus, The Global Womens Movement: Origins, Issues and Strategies.

London: Zed Books, 2004, 204 pp.

Introduction

This is a review article discussing three works, presented in chronological order.

The review draws attention to a new focus in feminist writing on the international/global.

During much of the 1990s (and after?), most feminist writing on the international sphere

was about gender and international relations (Grant and Newland 1991, Sylvester

2002, Peterson 1992, Pettman 1996, Tickner 2005). Most of these were limited by the

felt need to critique the discipline of International Relations. The international womens

movement or feminist internationalism just about reached their concluding chapters or

paragraphs.

There were, of course, exceptions, as with Cynthia Enloes cross-disciplinary and

bottom-up look at international relations (Enloe 2002). Or compilations on sex workers

(such as Kempadoo and Doezema 1998), but here we are clearly debouching into

discourses of globalisation and globalised resistance. The shift of feminist interest from

international relations to globalisation does not, as we will see, necessarily mean an

equal shift from the critique of domination or dominant discourses into a focus on rights,

resistance, and redefinition (Kempadoo and Doezemas subtitle). But there is something

about globalisation discourse which either permits or provokes a focus on not only

resistance but counter-assertion (Miles 1996 may be another forerunner here).

This paper does not claim to comprehensive, or even representative, coverage of

what has been published during the last five years or so, since this is a rapidly

expanding field of feminist concern. The selection, moreover, is biased toward the

South and Development biases I hope to question. Along the way I make reference

to other work in the field. In the Conclusion I will draw attention to contributions still

awaiting political response or theoretical review.

1. Many Feminisms and one internationalism?

Let us start with the claim of the Sinha, Guy and Woollacott book, as printed on

the back cover, and illustrated by a photo of middle-class European and Asian women,

some in Asian costume, many wearing cloche hats, under palm trees, at some

conference in the late-1920s:

Feminisms and Internationalism addresses the theme of the history of internationalism in

feminist theory and praxis. It engages some of the following topics: the ways in which

internationalism' has been conceived historically within feminism and women's

95

movements; the nature of and the historical shifts within imperial feminisms; changes in

the meaning of feminist internationalism both preceding and following the end of most

formal empires in the twentieth-century; the challenges to, and the reformulations of,

internationalism within feminism by women of colour and by women from colonised or

formerly colonised countries; the fragmentation of internationalism in response to a

growing emphasis on local over global context of struggle as well as on a variety of

different feminisms instead of a singular feminism; and the context for the re-emergence

of internationalism within feminisms and women's movements as a result of the new

modes of globalisation in the late twentieth-century.

This is an ambitious agenda. But so is the very title of the book, the first such of

which I am aware. We begin with quite extensive abstracts, revealing authors with roots

in Korea, Latin America, China, India, Iran and West Africa (?), as well as the more usual

North-American and West-European ones. In addition to the introduction and a set of

seven cases (the body of the book), we are offered a forum, followed by several review

essays. The authors of the seven articles are all new names to me - as are those of the

editors - which is again promising. The forum is led off by a veteran historian of Latin

American feminisms, Asuncin Lavrin. The respondents and reviewers include names

more familiar, at least to me, such as Leila Rupp, Mary J ohn, Francesca Miller, Spike

Peterson and Val Moghadam.

The editorial introduction provides further orientation to the collection. This is the

source of the blurb. I think, however, we immediately run into a problem here, because

the editors neither define nor discuss internationalism. As a matter of fact, they don't

define or discuss feminisms much either. But a useful contemporary understanding of

such can nowadays be assumed (and in any case is much discussed elsewhere in the

book). This is not the case for internationalism which, curiously for our fanatically

pluralist times, appears here in the singular.

The editors apparently looked for historical (or historians) contributions, and

seem to consider that such provide the necessary basis for further academic work on the

subject. Yet it seems to me that while we have an increasing body of historical work in

this field (see the books review articles and bibliography, as well as Waterman

1998/2001), what we lack is precisely theory. In the absence of a conceptualisation, a

model, or some organising hypothesis, we are likely to create something in which the

whole is less than the sum of the parts. The editors do argue for a certain orientation, but

this is a general and now commonplace one, seeking a mean between or beyond an

abstract universalism and a particularistic relativism. They also make much of

defamiliarising and decentering. But this implies that there exist theories, theorists,

schools, traditions or tendencies which require such. And, unfortunately, the one

classical liberal-feminist historical work worthy of this treatment (Bernard 1987) is

nowhere even referred to!

As a result of the above, the articles and reviews sections seem to be held

together more by reference to the international than to internationalism. There is,

therefore, in this collection much about feminism and (anti-)imperialism, or international

relations, and even development. The piece on Yemen makes no reference even to the

international and actually belongs to the abundant literature on feminism and

nationalism. And even if the collection is admirably sensitive to westocentrism it is not to

classocentrism. Although labour, socialism and international feminism are mentioned in

the introduction, they seem to be hidden from the following history. We are dealing here

96

almost exclusively with middle-class feminists and middle-class women (sometimes

aristocratic ones). I find this both detrimental to the project and somewhat puzzling.

My feeling is that the history of left and popular feminist internationalisms is likely

to provide more lessons for the future than that of the liberal and middle-class ones. The

latter are today abundant: the problem is precisely making them popular, radically-

democratic, egalitarian, and socially-transformatory (a nice way of redefining

socialism?). The only explanation I can come up with for this academic blindspot is the

international shift, in the 1980s-90s from a social-movement to a political-institutional

feminism, in which primary attention went to those who - in the past as in the present -

are most politically articulate and influential, who both read and write feminism. Or,

possibly, it was due to the domination of feminism in the 1990s (as much else in

academia) by discourse analysis, which focuses on meanings at the expense of doings.

This does not, of course, mean that the case studies are necessarily lacking in

either historical interest or contemporary political relevance.

Christine Ehrick's chapter on interwar (the European World Wars!) liberal

feminism in Uruguay has a fine feeling for North-South, South-South and Argentina-

Uruguay contradictions and dynamics, as well as for the class composition and

orientation of her particular movement. My feeling is that such national/regional conflicts

were inevitable in the period of national-industrial-imperial capitalism. Which does not -

as we will immediately see - mean they will disappear of their own accord during our

global-informational capitalist period.

Ping-Chun Hsiung and Yuk-Lin Renita Wong employ an understanding of

difference feminism (my phrase) to identify independent feminist/women's movement

voices in China, which are seeking their own understandings independent of both

Western feminism and the Chinese party/state. Each of these claims to speak for

Chinese women and they are (therefore?) in diametrical opposition to each other. There

is, however, a curiosity here since the authors associate their Western feminism, which

they specify quite distinctly, with the confrontational paradigm projected in the NGO

model (ix). In so far as the Western NGO model, both nationally and internationally, has

been increasingly criticised precisely for its excessive intimacy with the state/interstate

(Alvarez 1998), there seems to me a possibility that this NGO model and the Chinese

feminist strategy might meet - but at an increasingly problematic place for the

development of a global feminist movement!

Now: most of the earlier-mentioned shortcomings are more than compensated for

in the exchange between Asuncin Lavrin (on Latin America), Leila Rupp (the Centre),

Mary E. J ohn (India), Shahnaz Rouse (on Islam) and J ayne O. Ifekwunigwe (on

borderland feminisms). The 30 or so pages of discussion do not relate closely to the

contents of the book. What they do is to begin a cross-

national/regional/cultural/epistemological dialogue on women and internationalism that

has not previously existed.

Lavrin, who launches the discussion, notes the particularity of Latin American

(LA) feminism in successive periods, but she rather emphasises its specific contribution

to the international (beyond LA) than its participation in such. She also identifies a sharp

debate within LA, between what one might consider an indigenista feminist (one who

tends to fetishise the indigenous, as distinguished from those who otherwise express it)

97

and those more open to the international. She also shows a welcome class sensitivity

where she states that:

It has been argued that theory is necessary to feminisms for opening

channels of understanding across national boundaries because theory

has the universal quality that makes feminism internationalYet, the

dilemma of how to make theories accessible to women without formal

education becomes more puzzling the more sophisticated the theories

becomePerhaps the most important task of international feminism is to

find that ample theoretical framework capable of embracing the largest

number of female experiences. (186)

This is, again, an important reflection on international feminism if not on feminist

internationalism. And although she echoes the common Northern feminist admiration for

the achievements of the LA and Caribbean feminist encuentros, she seems to have

missed the one in Chile, 1996, at which previously invisible or repressed tensions

exploded in not only a disruptive but also a destructive manner.

Leila Rupp has published a book on three or four major international 19th-20th

century organisations of what she herself calls elite, older, Christian women of

European origin (190). Although she might seem to be there reproducing the limitations

of the collection under consideration, her ideas on how to approach/understand feminist

internationalism are actually much broader. She argues for looking at this less in

ideological terms than in those of the senses and levels of collective self-identity: e.g.

organisational, movement and gender ones. In such terms, she suggests, what is

important about the conflict Lavrin mentions is less the ideological difference than the

fact that the parties involved are talking to each other about it. If her first remarks

suggest an interesting research methodology or project, the second might be taken as

suggesting the increasing centrality of communicational form to a contemporary

internationalism. Rupp concludes on the necessity for looking at feminisms and

internationalism (singular again!) from national, comparative and international locations.

Then, in a wisely iffy sentence, she argues optimistically for the promise of global

feminisms. If nationalism and internationalism do not have to act as polar opposites; if

we can conceptualise feminisms broadly enough to encompass a vast array of local

variations displaying multiple identities; if we work to dismantle the barriers to

participation in national and international women's movements; if we build on the basic

common denominators of women's relationship to production and reproduction, however

multifaceted in practice; then we can envisage truly global feminisms that can, in truth,

change the world (194).

Mary E. J ohn, from India begins by recognising South Asian feminist ignorance of

Latin America (an ignorance which, I can assure her, has in the past been blankly,

cheerfully or shamefacedly reciprocated). She therefore begins by informing Lavrin, or

Latin America - or in any case us - of the history of Indian feminisms. She continues with

a challenging reflection on the manner in which globalisation has undermined simple and

traditional meanings and oppositions between the local and the global, given the

extent to which globalisation, even in its early colonial manifestations, helped create the

contemporary local manifestations of Hinduism and caste. She then addresses the

problematic concepts of pluralism and diversity, emphasising (Thank Goddess!) what I

earlier suggested, that If feminism is not singular, neither is internationalism (199). She

continues with examples of existing or possible internationalisms rooted in the

98

subcontinent. And ends, again optimistically, on the possibility and necessity of more

egalitarian and dialogic Western collaborations, new perspectives on the South Asian

region and the Indian diaspora, and attempts to rethink South-South relations. (202)

Shahnaz Rouse's interrogation of religious difference from what one might call

the-point-of-view-of-internationalism has a particularly sharp cutting edge. She continues

the line traced by Leila Rupp, criticising the academic shift: 1) from a materialist to a

right of centre, culturalist, even a civilisational focus, b) to a kind of orientalism in

reverse, and c) an ontology of difference, and a new exclusiveness (206). This is

fighting talk, informed by a spirit of cosmopolitanism, egalitarianism and solidarity (i.e.

internationalism?). But if she may here be criticising her academic or ethnic sisters, she

cuts equally radically into a classist feminism. Echoing, again, earlier forum

contributions, she argues for a retreat (an advance surely?) from the politics of

difference, whether religious or secular, to a politics of experience:

What is called for is a return to the everyday as problematicThe

starting point here is not discourse but experience, fraught as that notion

may be, and implicated as it is, in representation itself (in the dual sense,

figurative and literal)Rather than posing cultural authenticity in reified,

de-historicised ways, we need to examine how capitalism creates

difference in seemingly totalising ways but which if examined more

closely reveal the close link between existing differences and power

relations: secular and religious discourses themselves being two of

these. (208)

Capitalism. Now that is a word, and world, which I would have thought relevant to

a discussion about the past, present and future of feminism and internationalism! I may

be revealing my own particular particularism if I admit that I have, here, no major

objection to it being referred to in the singular. I would only suggest two directions in

which capitalism (OK, and capitalisms) might be usefully specified if studies of women

and internationalism are to be advanced. The first, already implied, is in terms of

historical phases, particularly the threats, promises and seductions of its contemporary

globalised form. The second, hardly mentioned, never theorised and barely strategised

is that of money - simultaneously the most abstract and concrete manifestation of

capitalism. This is something which, apparently, the women internationalists - handing it

out or receiving it - still consider difficult to talk about, whether in mixed company or in

public. While their grandmothers, in the cloche hats, might have considered talking about

this simply bad taste, the granddaughters presumably see it as a discourse of vulgar

materialism. Introducing the everyday into the analysis, theorisation and strategising of

feminist internationalism may therefore be more difficult than our last author imagines. I

will return to this matter below.

2. Globalisation and gender

Weighing in at what feels like a healthy kilo, over 350 pages in length, containing

some 20 contributions, and co-edited by well-known specialists, this special issue of

Signs makes a substantial feminist contribution to a developing area of study and

struggle.

99

An Editorial sets out the intentions of Gender and Globalisation (henceforth

G&G). These are, in the first place, obviously, to fill a lacuna in critical theorising about

globalisation - its customary gender-blindness. Whilst feminist political economists and

others have recognised the significance of women's subordinate role in

internationalization/globalisation, the editors are concerned about the absence of

address to women's centrality within, agency in respect of, and social movements in

opposition to, globalisation. They are equally concerned that feminist theory should

surpass such simplistic binary oppositions (also feminist ones) as globalisation from

above/globalisation from below, global capitalism/local social movements, and northern-

imperial social movements/southern (anti-imperial?) ones:

The articles in this special issue complicate these approachesIn

particular, they address the ways in which political economy, social

movements, identity formation, and questions of agency are often

inextricable from each other. They discuss the participation of women

trying to better their conditions as crucial aspects of globalisation, thereby

contradicting the assumption that globalisation is a process imposed

solely from above by powerful states or multinational corporations. (944-

5).

The attempt to look at globalisation both as a gendered process and in a

dialectical manner is carried out through a set of articles, exchanges and book reviews.

We have a diverse series of contemporary studies, in which are considered the relation

of gender and sexuality to globalisation and nationalism, several of which reflect critically

on existing feminist and other globalisation theories. Another group of articles considers

the relationship between women's activism and globalisation, again criticising facile

assumptions concerning international solidarity. There follows a series of brief dialogues,

commentaries and roundtables on aspects of globalisation: these are as varied as: the

globalised prison industry, the international division of labour, the anti-globalisation

movement, international financial institutions, Chinese feminism, studies of the Middle

East, and women-and-globalisation studies more generally.

Whilst the collection contains a number of admirable pieces, I feel it lacks overall

impact. This may be because the Editorial actually goes further than what follows. We

are certainly presented with challenges to simplistic approaches, malestream or

feminist. And much is made of agency to the point of characterising certain collective

behaviour as agentive, an adjective - or is it an adverb? - that I won't mind never seeing

again. But the Editorial fails to prepare us for the extent to which the papers are

addressed to US academic feminist concerns and theory, which are, inevitably, a limited

part of, or angle on, our increasingly complex and globalised world disorder. Even when

we move from agency to movements, the latter turn out to be mostly Non-

Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and their international relations. I miss the Latin

American feminist demand to move de la protesta a la propuesta (from protest to

proposition). But, then, the vibrant international/ist movement and thought of and on

Latin American women and feminism is also absent (Alvarez 2000, Barrig 2001,

Mendoza 2001, Olea Maulen 1998, Sanchs 2001, Vargas 1999, 2001, 2003, as well

as Thayer below). My feeling is, then, that whilst we have a worthy supplement to other

feminist work on globalisation, we have here no noticeable advance.

100

I have other problems with the editing of the collection and writing style. I am not

accustomed to finding feminist writing lacking relevant focus or stylistic fireworks. But the

35 pages on the autobiography of a J amaican Creole woman entrepreneur and

adventurer with no anti-colonial, anti-racist, social reformist or feminist characteristics

seems entirely out of place in this collection, whatever it might tell us about the complex

interplay in the nineteenth century between gendered mobility, black diaspora identity,

colonial power, and transnational circularity (949). Elsewhere in the collection I felt

somewhat overwhelmed by a uniform US academic malestream style, in which the

personality and subject position of the author is buried under layers of formal stylistic

ritual. I do not know whether this is responsible for the considerable overlap or repetition

within and across contributions, but it has a dulling impact.

Having got this all off my chest, let me mention some pieces that impressed.

These include Suzanne Bergeron's useful overview of political-economic discourses on

globalisation; Carla Freeman's case study of Caribbean women who combine their day

jobs in the white-collar, but proletarianised and globalised data-entry industry, with

spare-time, globalised petty-trading, reveals the limits of any simple class analysis; two

pieces on transnational women's/feminist NGO networking, one on Russia, one on

South Africa, show how contradictory such relations can be; one of the dialogues,

on/against the World Trade Organisation brings us close to where - I hope - the new

wave of global feminist activity will be centred. I was, finally, fascinated by a study of the

Miss World contest in India, precisely because of its address to the novel, complex and

contradictory responses to such of women and social movements locally. I will return to

the last two items in more detail, starting with the Indian one.

Rupal Oza's 'Showcasing India: Gender, Geography, and Globalisation', is about

the protest surrounding the 1996 Miss World contest in Bangalore. There were here two

broad protest movements, a rightwing Hindu-based movement, Defending Indian Culture

From Westernization, and a leftwing socialist and/or feminist one Defending The Indian

Economy From Globalisation. Whilst there were distinct differences between the two

movements, there was a coincidence in 1) seeing representations of women's bodies as

endangering India's borders, 2) making the Indian nation and/or state the point of

positive identity, 3) failing to come to terms with women's own agency and sexuality, and

4) subordinating women and sexuality to the economy, the nation and the state. Oza

draws a conclusion of more general relevance:

The construction of resistance at any level that is predicated on

structures of oppression or suppression at other levels or is contained

through them is problematic from the start. Equally problematic are the

assumptions of political hierarchy whereby gender and sexual politics are

put on hold against the priority of local resistance to the overarching force

of globalisation. The underlying assumption here is that gender and

sexualityare not already constitutive of globalisation and of local

resistance. The political hierarchy in this context, then, is a ruse for

denying agency to gender and sexuality. These issues have been raised

in the context of the struggles for women's rights and the structural place

of the women's movement within nationalism. Therefore, conceptually

progressive politics, when framed in terms of local resistance to

globalisation yet dependent on adherence to hegemonic structural

101

positions within a 'new' patriarchy, is politically dangerous and

theoretically precarious. (1090)

Although Oza's case deals with a nationally-identified and bounded

women's/feminist protest against globalisation, it throws light on the anti-globalisation

movement worldwide. Here, too, we find leftwing movements that, because they see

globalisation in terms of 'the highest stage of imperialism', must pose against it

something like 'the highest stage of nationalism', i.e. a socialism both nation-state-based

and defined. In, however, posing the Nation against the Global, such movements not

only find themselves in uncomfortable proximity to a rightwing both hated and feared, but

are also disqualified for two essential contemporary tasks: 1) developing what has been

a traditional internationalism into a global solidarity movement and discourse (i.e. one

that, precisely, displaces the state-defined nation from the centre of politics); 2) re-

inventing the democratic nation-state in the light of the global and gender justice

movements. The international women's movements, and feminisms, proposing post-

national identities, can make a major contribution to these struggles. But do they do this,

in the case of the major international movement of our day, the 'global justice', 'anti-

corporate' or 'anti-capitalist' movement?

Kathleen Staudt, Shirin Rai and J ane Parpart's discussion suggests that women

have been marginal to this latest internationalism, and they seem to consider the anti-

globalisation movement responsible for this absence. I would consider it, rather, the

equal responsibility of the women's movements and the feminists (as with the late, light

presence of labour, and the virtual absence of African-Americans in Seattle)! It is true

that, whilst feisty women and prominent feminists have participated in, and are even

spokespeople for, the anti-globalisation movement, there has been restricted women's

movement presence or explicit feminist engagement here. I can only put this down to the

previous over-politicisation (state-centredness) of the women's movement, and to the

engagement of much of its leadership with inter/national (again: inter-state and state-

like) policy-making institutions, or their gender advisory committees. This proposition is

lent credibility by G&G and in two ways. The first is explicit, lying in the critiques of

international 'ngo-isation', the second is implicit, lying in the paucity of contributions on

actual women's/feminist movements confronting globalisation.

There is no shortage, in the real world, of such movements, nor, actually, of

feminist address to such. Two references make the point. The first is the book on

globalisation, democracy and women's movements by Catherine Eschle (2001). The

second is a paper by Millie Thayer (2001) on the relationship between popular women

activists at the global periphery and transnational feminism. Here a parenthesis may not

be out of place.

The Eschle book does not appear promising, given that its primary focus is on

democracy rather than movements and that its form is that of a critique of the literature

(already over-represented in the G&G collection). But she is concerned precisely with

the necessity and possibility of a feminist contribution to a reinvention of democracy in

the era of globalisation. And her understanding of feminism and democracy is one that is

dependent on social movements. So, after a long march through and beyond the

commonly state-centric theories of democracy, she addresses herself energetically to

'Reconstructing Global Feminism: Engendering Democracy' (Chapter 7). Here she

stresses the necessity for the women's movement to be anti-capitalist, as also to

102

develop 'transversal' (horizontal, reciprocal) relations, and to democratise internally. I do

not intend to set up Eschle against G&G, in so far as she develops a note and

orientation already present within the collection. Moreover, there are limitations to both

her conceptualization and her evidence. 'Transversal' is an evocative but loose term. I

would have thought one could say more by developing the classical notion of

'international solidarity' (for my own attempt see Waterman 1998/2001: 235-8). There is

also a limitation in so far as her case studies are drawn from a secondary literature that

is often stronger in the mode of advocacy than of analysis. Although, finally, she is

concerned that the international women's movement be anti-capitalist, she hardly

exemplifies this. So it may be that my favourable comparison with G&G lies mostly in her

'movement-centredness'.

Millie Thayer's provocative title is 'Transnational Feminism: Reading J oan Scott

in the Brazilian Serto'. Her rich case study and theoretical argument runs as follows:

Fieldwork with a rural Brazilian women's movementfinds another face

of globalisation with more potentially positive effects. These activists

create meaning in a transnational web of political/cultural relations that

brings benefits as well as risks for their movement. Rural women engage

with a variety of differently located feminist actors in relations constituted

both by power and by solidarity. They defend their autonomy from the

impositions of international funders, negotiate over political resources

with urban Brazilian feminists, and appropriate and transform

transnational feminist discourses. In this process, the rural women draw

on resources of their own based on the very local-ness whose demise is

bemoaned by globalisation theorists.

Again, I do not wish to pose Thayer against G&G. Indeed, the intention of the

G&G Editorial seems to be rather well exemplified by her paper. Nor is Thayer without

her own shortcomings or lacunae. She surely misreads Manuel Castells' masterwork on

the information society, since he actually gives women's/feminist movements the space,

scope and transformatory significance he denies to workers' ones (Waterman 1999a)!

And whilst she suggests a virtuous spiral between, in this case, Northern and Southern

feminisms/women's movements, we are not shown how the Southern experience or

ideas feeds back to the Northern (or international) movement, rather than to her as a

Northern feminist academic. It is, again, the tone of the writer that is at issue here.

Gramsci would recognise the disposition of both writers towards the movement:

'scepticism of the intellect; optimism of the will'.

My final thought on G&G is that it cast its net too wide. The field - to move from

fishing to agriculture - has actually been better tilled than the Editorial suggests. See, for

example, Dickenson (1997), Harcourt (2001), Wichterlich (2000), and two review articles

(Eschle 1999 and Waterman 1999b). What is now needed may be more narrowly-

focused collections. And, of course, more women's movements making their customarily

pertinent, outrageous and utopian contributions to the major internationalist movement of

our day.

103

3. A global womens movement: dawn or DAWN?

Let me start by saying that the Peggy Antrobus book is a brief and welcome

introduction to the global womens movement, that as such it fills a long-felt-want, and

that it is to be recommended to those new to, unfamiliar with, or who feel they should be

allied with, the womens movement. It would - it will - make an excellent text for those

doing womens studies, as to those doing social movement studies, whether globally or

more locally. Because of its direct treatment of the movement I am going to give it

extended attention.

Antrobus is a veteran of the movement, from the Anglophone West Indies, with

experience in government, academia, and womens NGOs. These activities have been

national, regional and in particular international/global. She has written a readable

account that manages to combine the Political, the Theoretical, the Professional and the

Personal, in a seductive narrative. She is up-front about who she is and where she

comes from, about where, when and how she became a feminist ( in 1979, at a feminist

workshop). She thus places herself on the same plane as her argument, making both

eminently open to both approval and criticism. I intend to confront these in the forceful

but constructive manner they invite and deserve. Her theoretical/conceptual propositions

are clear and a provocation to thought:

Is there a global womens movement? How can we understand such a

movement? How can it be defined, and what are its characteristics? My

conclusion is that there is a global womens movement. It is different from

other social movements and can be defined by diversity, its feminist

politics and perspectives, its global reach and its methods of organising.

(9).

This is all in Chapter 2. But such specifications continue throughout. The work

concentrates on the period covered by the major UN conferences concerning women,

starting with the Development Decade of the 1960s-70s (Chapter 3), The UN Decade for

Women, 1975-85 (Chapter 4), the global conferences of the 1990s, particularly the

World Conference on Women in 1995 (Chapter 6). However, Antrobus begins and ends

her book with referemces to the World Social Forums and Global J ustice Movement of

the 2000s (3-5, 175-6, and, implicitly, Chapter 10). Her UN-inspired chapters are

interspersed with one on the lost decade of the 1980s (Chapter 5), on movement

strategies (Chapter 7), on present and future challenges (Chapter 8) and leadership

(Chapter 9 but also Chapter 6). In the rest of this review I want to reflect on at least part

of what has been briefly mentioned above.

Reconceptualising the global womens and feminist movement

Womens movements, our author argues, are different from other movements,

but she nonetheless specifies their problems in a manner common to specialists on

social movements more generally:

The confusion and contradictionsreflect the complexity of a movement

that is caught in the tension between what is possible and what is

dreamed of, between short-term goals and long-term visions, between

expediency and risk-taking, pragmatism and surrender, between the

practical and the strategic. (11)

104

Whilst accepting the first of her binary oppositions/tensions as an inevitable part of the

international womens (or labour) movement, I would stress the second as the dynamic

and emancipatory tendency. This goes for all her binaries except that between

pragmatism and surrender, which does not seem to belong to the set.

Summarising, Antrobus considers the womens movement as political, as

recognising womens relationship to social conditions, as processal, as posed against

patriarchal privilege, as beginning where and when women recognise their separateness

and even their alienation, marginalisation, isolation or abandonment within wider

movements for social justice or transformation (14). Fair enough.

But possibly not far enough, since Nira Yuval-Davis (2004), for example,

powerfully questions the human-rights feminism that has largely conquered - and

encapsulated - the international movement over the past decade or so. And Ewa

Charkiewicz (2004a) has suggested that the corporations (often invisible within global

feminisms) and their bio-political impacts need to be the, or at least a, primary subject for

feminists. All this implies tensions within the global womens/feminist movement that are

rather more complex than our author allows for.

Antrobus also specifies certain characteristics that differentiate the womens

movement from others: the recognition of diversity, its feminist leadership (but which of

57 often-competing, sometimes-warring, feminisms?), its global reach. She distinguishes

between an international and a global movement, identifying a movement between the

one and the other during the period she covers. This is a useful distinction, since even

once-emancipatory internationalisms increasingly became internationalisms. But, for me,

a global movement means one that not merely surpasses national internationalisms but

which is holistic. And the creation of such a movement is, surely, something to be yet

constructed rather than simply asserted as existing (as if it were a simple reflex against

neo-liberal globalisation?).

So, the theoretical assertions of this book have to be seen as introductory and

partial. Necessary, perhaps, but in no way sufficient. And revealing of certain subject

positionings that the author may admit to rather than problematise.

Priorities: the South, the UN and the NGO(s)

Peggy Antrobus comes from the South, the UN and the NGO(s). These are all

obviously part of the movement but I see no good reason to privilege them to the extent

that the other parts (the North, the old East) become background, that other

spaces/places/levels (the street, the community, the workplace/union, the Web, the

culture) disappear, appear as secondary, and that the NGO appears to be the primary

form taken by the movement.

The South: I find in the index some 14 or so references to places in the South

and only 3-4 to those in the North (including the no-longer-actually-existing USSR). This

imbalance is not simply because of where the author comes from. It expresses a notion

that the global movement is led by the South. This is not an opinion that would

necessarily be shared by all her Southern sisters. Antrobus considers that the movement

has been transformed since the 1970s

105

largely through the influence of Third World feminists and women of

colour in North America(1).

If this is how she starts, then she ends with the challenges confronting

a global womens movement built through the leadership of Third World

women(185).

Perhaps a case could be made for such a vanguard role, but then only on the basis of

evidence and argument here absent. I would have thought it closer to both the reality

and the need to consider the North/South relationship a dialectical one, in which mutual

political influence and dialogue was the major force. This is to leave aside the matter of

whether, in talking of the dialectic within the movement, North and South should be

unproblematically accepted as primary categories.

The United Nations: Although the influence played by womens presence and

feminist analysis in relationship to the UN is certainly one determinant of the growth of

the womens movement, it is not the only one, or even - one hopes for the future - the

dominant one. In so far as it is or was such, then this is surely a highly problematic

influence that requires, well, problematising. Peggy Antrobus is not, of course, unaware,

of the danger represented by what I would call the inter-state sphere:

Of course there are risks. Many writers have referred to the

bureaucratisation of the movement. In a sense the movement itself

became a victim of its successful advocacy.[M]any activistshave

faced accusations of being co-opted, or having sold out on the

movement. (61-2)

Antrobus sees this, however, as a strategic problem (engaging with the state/ preserving

autonomy) rather than a theoretical one. In so far, however, as we understand an

increasingly corporatised and corporatist UN as bent on, well, incorporation, then we

need to recognise the profoundly contradictory role it plays with respect to any

emancipatory movement - of workers and indigenous peoples as well as women

(Charkiewicz 2004b). Drawing from Marxist theory on commoditisation and fetishisation,

the strategy issue can be expressed more pointedly:

Ultimately, these questions point to the problematic of organisation, of

building bridges, of establishing links, learning from mistakes, de-

fetishising our relations to the others, reaching out and being reached,

sharing resources and creating commons, reinventing local and trans-

local communities, articulating flows from movement to society [rather

than from the movement to inter/state instances. PW] and vice versa. (De

Angelis 2004:12)

Massimo De Angelis might here be expressing ideas learned, amongst others,

from feminist analysis. But there are feminists who can also learn from him about the

major problem confronting the movement.

The NGO(s): Antrobus recognises, again, the ambiguity of the non-governmental

organisation as form, and even the problem of NGO-isation (153-4). But this is again

presented as a strategy problem and is not theorised. Nor, for that matter, I think, even

106

really strategised. The strategy problem would be a matter of where, how and in what

way, the NGO form relates to the womens movement. In so far as the dominant 19

th

century form of mass mobilisation/control, the socialist/populist/nationalist political party,

is in a condition of disrepute and decline (hopefully terminal), the rise of the NGO

providing technical, intellectual and communicational expertise to and support for social

movements is to be welcomed. But, then, this would be not so much a non-

governmental organisation (dependent for its identity on that to which it is opposed) but

an anti-hegemonic instance attempting to surpass capital and state (patriarchy, racism,

war, etc), and providing support for, rather than the substitution of, recognisable social

movements. The concept of NGO-isation, or ongizacin, has been recognised in Latin

America as the major problem facing the womens movement in Latin America (Alvarez

2000). Once again the tension between management and emancipation rears its J anus

head.

Things do not get better. Peggy Antrobus is a long-standing member of DAWN

(Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era). This is one of a dozen, or a

hundred, of rather professional, socially-critical, international feminist NGOs-cum-think-

tanks. This particular NGO is honoured with some 21 references in her index, as against

27 for feminism in general! Moreover, there is no word of criticism for DAWN. Which

means that here we are into identificatory-celebratory discourse. This, as far as I am

concerned, suggests the imprisonment of DAWN within a practice common to the old

social movements (national, labour).

The global womens movement and the secret of fire

It is evident, from this, that feminism and the womens movement have, despite

significant breakthroughs, not necessarily discovered the Secret of Fire that releases the

new from the old. They may have contributed to such in dramatic and significant ways,

but they do not play globally the role of vanguard. And since such a role is anyway

increasingly regarded with an Argus eye within the new movements, this is not such a

bad thing either. Right now, and for the past five years or so, for example, the global

womens movement has needed to learn from a global justice movement that has

learned from it. Or from those parts of the movements, those theorists, who have done

so. Yet the global womens movement, and even some of the more sophisticated

feminists still have to move beyond the moment of excision from the old inter/national

left (Vargas 1992, citing Gramsci), to fully engaging with and co-creating the new global

social emancipation.

Although our author recognises, again, the way in which external funding can

blunt the political edge of the movement (155), this is hardly adequate to the case.

Foreign funding (from the books Rich, Guilty and Exhausted North to its Poor, Innocent

and Energetic South) is, at least in Latin America, the sine qua non of the movement. It

would be more helpful to recognise that we are talking of foreign-funded feminism and

then to confront the implications of this for the womens movement in not only the South

but globally (where it may be foreign in the sense of financiers and foundations with

quite other motives than emancipatory ones)!

Whilst the global womens movement is increasingly aware of neo-liberalism and

capitalist globalisation, it seems to believe that its collective subject, its theoretical

inspiration and its discourse frees itself from the political-economic determinants that

DAWN is quite ready to recognise as operating, well, globally. This and related de-

107

radicalising pressures have been recognised for one hundred years by socialist

specialists on the inter/national labour movement (Waterman and Timms 2004:182-5),

so why not by a feminist for the womens one? At the European Social Forum, London,

2004, libertarian critics of its top-down structure and commercialised processes issued

the slogan, Another World is For Sale!. A more forceful critique is therefore required

than this author gives us of managerialism and commodification within what is here

championed as an emancipatory movement. Reducing the womens movement to the

level of other social movements would also mean releasing potentials presently

imprisoned.

The masters tools and the deconstruction of the masters house

One last complaint, mentioned above, but which is much more widely spread

than in this book alone. This is the avoidance of the word capitalism even by feminists

who are or were once socialists. Capitalism does not even get an index reference in

Antrobus. Capitalists, mostly after all male, white and patriarchal, call it capitalism, and

are proud of it. So why cannot it not be so named by feminists, who could and surely

should condemn it? This cannot be solely because of their justified criticism of the

archaic political-economic determinism of patriarchal socialists. So it has to be due to

either a desire to be salonfhig (acceptable in the salons within which they have been

speaking, to the funders they are dependent upon), or a restriction of their utopia to a

kinder, gentler global capitalism, a global neo-Keynesian order for which no convincing

feminist case has been made. Fortunately, anti-capitalist feminist networks have

appeared in the new global agora, such as the Global Womens Strike highlighted by

Antrobus (193-2) and the rather more-significant World March of Women (see below and

http://www.marchemondiale.org/en/charter3.html).

On the other hand, there is a word well worth avoiding like the proverbial plague,

this being development. In so far as this actually means the development of capitalism

and/or the development of the nation-state it is a Northern, hegemonic and colonising

discourse. Its employment by such Southern activists/scholars as Peggy Antrobus (and

an endless series of womens NGOs) implies a significant limitation on attempts to

develop a meaningfully emancipatory global feminist discourse. It also reinforces a

division between the developed and developing worlds which a global feminist

discourse surely needs in the era of capitalist globalisation to surpass. As the Black

feminist activist and writer, Audre Lorde (1984), once said, The Masters Tools Will

Never Dismantle the Masters House.

New addresses, new agoras for the global womens movement

Antrobus makes generous reference to the World Social Forum and the global

justice and solidarity movement, to whose birth feminists have made a certain

contribution. But, once again, hers is not a critical treatment. By this I mean

critical/committed attention to the nature of the movement and the forum, and to the

presence of women and the role of feminists, within both (compare NextGENDERation

Network 2004). This might seem an excessive demand given the newness and the

novelty of both. DAWN, however, has not only been present within the WSF since at

least 2002 but is a member of its International Council, and its website provides access

to major feminist activities within the WSF in Mumbai, 2004

108

http://www.dawn.org.fj/global/worldsocialforum/ intfemdialogue.htm. Yet our author

mysteriously claims that

With their overwhelming crowds, simple slogans and easily understood

banners, these demonstrations and campaigns are not the spaces of

dialogue. Neither is the Forum the space for the negotiations that have to

take place with men, and some women, on issues of sexism with the

social movements. (176, as also 116-7)

Why, in the name of The Goddess, not?

The Fora seem to me the presently privileged space for such global dialogue.

And although the Feminist Dialogue at Mumbai may not have highlighted womens place

and a feminist understanding of the Forum and the new movement, there is no reason

why this should not be so raised by feminists at an event in which almost 50 percent of

the participants are women! Where else could the feminists and the womens movement

be where they will be surrounded by such a high percentage of young, ethnically-

pluralistic, democratically-inclined, activist and radical women? Negotiating across tables

or in corridors with male inter/state bureaucrats of a certain age? Finally, of course,

womens presence and feminist attitudes do not express themselves solely in verbal

dialogue but in cultural forms that the movement previously celebrated or invented. The

most memorable feminist presence at the WSFs is, therefore, probably that of the tiny

Articulacin Feminista Marcosur (see below), with its simple slogans and easily-

understood bannerstargeting fundamentalisms! But this book is itself a politics-fixated

one and gives little or no attention to either culture or to the cyberspatial communication

that is becoming both a condition for and an expression of global feminism (compare

another Zed Book Antrobus ignores, Harcourt 1999, particularly the contribution of

Agustn 1999).

Whilst Peggy Antrobus might prefer some other space (Yuval-Davis 2004 also,

but neither indicates which) for such dialogue, her position actually reveals the late, light

presence of the womens movement and feminists within the newest movement in

general and the Forum in particular. Prominent exceptions would be the World March of

Women http://www.marchemondiale.org/en/index.html and the Articulacin Feminista

Marcosur http://www.mujeresdelsur.org.uy/, neither of which is mentioned in Antrobus. It

would seem to me that the the past fixation of many feminists on Patriarchy, on the

Political, and on the UN, have blinded it toward Capitalism, Globalisation and, thus,

delayed their forceful address to what is less a New Social Movement (1960s-80s) than

a newer Global J ustice and Solidarity one (1994-?).

Evidence for this absence is provided by the regular encuentros of the Latin

American and Caribbean Feminists (also mysteriously ignored by Antrobus). As early as

1996 a discussion document dealing in part with globalisation and the global womens

movement was addressed to the Encuentro, in Cartagena, Chile (Vargas 1996). It led to

no recorded discussion, the event being dominated by a fundamentalist feminist attack

on the rest of the movement as patriarchal feminist (Waterman 1998/2001:Ch.6)! In

2002, the 9

th

Encuentro met in Costa Rica. It was addressed precisely to globalisation -

or at least to Resistencia activa frente a la globalizacin liberal. Despite this title and a

provocative if problematic discussion document (Facio 2003), the Encuentro hardly

addressed the matter. And it had nothing to say about a WSF that was due to take place

a couple of months later in the same continent! There is here clearly a danger of self-

109

referentiality, of a movemen in the direction of a self-isolating community. Here is

another case. I have suggested above that the World March of Women has been more

actively engaged (and visible) in the Forums than other feminist initiatives. Yet it has

been criticised by other feminists for attempting to hegemonise womens activities within

the European Social Forum, Paris, 2003 (NewGENDERation 2004:143). In mentioning

such cases I am clearly not proposing these as virtuous alternatives to those bodies

mentioned by Antrobus, nor even to her incrementalist orientation. The global womens

movement simply requires from its participants and its observers as much scepticism of

the intellect as optimism of the will (Gramsci again).

Literary lacunae

Whilst one cannot expect of such a short book a complete rundown of the

relevant literature, it might not be too much to ask that it show awareness of major books

or articles by compaeras who have dealt and are increasingly dealing with the

same subject. Here are some such (which may include material published after the

books deadline): Sonia Alvarez (2000), Alvarez, Faria and Nobre (2003), the classical

liberal feminist work in this area by J essie Bernard (1987), J ohanna Brenner (2003,

2004), Zillah Eisenstein (1998), Catherine Eschle (2001, 2003, and Eschle and

Stammers 2004), the Peggy Antrobus co-edited(!) special issue of Canadian Woman

Studies (2002), the Sinha, Guy and Woolacott collection (1999), Virginia Vargas (2001,

2003), Christa Wichterich (2000). For the flavour of just one of these, which does

consider both feminism and the global justice movement critically, consider this:

Conflicts and tensions around gender relations and feminist politics within the

GJ M offer hope as well as words of caution. Conflicts exist because women activists and

their organisations are serious players on the political stage, contesting male dominance

not as outsiders but from within the networks of the GJ M. Whether feminism will come to

inform the radical vision and the everyday politics of global justice activists depends on

how well the movements are able to sustain political coalitions that are participatory and

willing to engage in dialogue. Movements that make a space for the political and

strategic interventions of working class and popular feminist activists and their

organisations will constitute a powerful pole of attraction, an alternative for those [in both

movements? PW] who now believe they have no choice but to compromise with the

neoliberal order. (Brenner 2004:33)

I started by recommending this book and I still do. If the Zapatistas called for one

no and many yesses, this work contributes to both the no and the yesses. If the World

Social Forum says Another World is Possible!, then another such book on the same

subject is not only possible but necessary. There can, thanks to capitalist globalisation

and the growing movement against and beyond it, be little doubt that we will see many.

Conclusion

In the fear of having above expressed too much scepticism of the intellect, and of

making only gestures toward optimism of the will, I thought I had better make a final

check on the not-quite-ubiquitous web, seeking for feminist internationalism, global

feminism and related terms. Obviously such a search is most likely to identify work by

Anglo-Saxon academics, or others writing in English. And, indeed, this was the case.

Whilst all kinds of internationalist feminist activity might be building in the World Social

110

Forum process, I identified some significant contributions to a new understanding of

globalisation, feminism and internationalism from North America.

The first of these was a special issue, or section, of the US journal, Socialism

and Democracy, on Gender and Globalisation: Marxist-Feminist Perspectives,

http://www.sdonline.org/backissues.htm, guest-edited and introduced by Hester

Eisenstein (2004). Even where original, interesting and informative, however, the section

seems to have been motivated less by a concern to renew Marxist-Feminism in the light

of globalisation than to restate the former in the face of the latter. And even, at one point,

a concern to restate a socialist internationalism, in the face of a global solidarity

movement that relativises a state-defined-nationalism. Thus, an interesting contribution

by Tammy Findlay (2004) appears to argue that the Canadian-initiated and Canada-

based World March of Women (WMW) is a local and national movement that has some

kind of international expression or extension an argument unlikely to be welcome to

that increasingly global solidarity network itself. The problem of Finlay and of a whole

section of the Canadian left identified with progressive nationalism/internationalism, is

that it still seems to see the national and the global as separate places or levels, rather

than as an increasingly mutually-determining complex, requiring emancipatory strategies

that are simultaneously local, national, regional and global. Whilst the WMW quite

obviously has the national origins and base indicated above, I would challenge Findlay

to read this out of the Charter the latter launched late-2004. It is interesting to note,

finally, that the contribution with the most bite on gender, globalisation and the

international womens movement and the left - is the one which makes no reference to

Marxism or socialism (Barton 2004)!

The second item I identitifed appeared to my eyes (as a Liberation Marxist),

more promising, even if oriented toward womens studies rather than the womens

movement. This was a workshop, Towards a New Feminist Internationalism,

http://ws.web.arizona.edu/ conference/ workshops/1a_description.html, organised in

2002 by Miranda J oseph, Priti Ramamurthy and Alys Weinbaum.

Anyone interested in moving on from this review article could do worse than start

with these two documents. And if this seems an unconventional conclusion to this review

article, I would hope it will encourage readers to treat the piece as just one intervention

in a rapidly-developing processand dialogue?

Bibliography

Agustn, Laura. 1999. They Speak But Who Listens?, in Wendy Harcourt (ed). 1999.

Women@Internet: Creating New Cultures in Cyberspace. London: Zed. Pp. 149-

55.

Alvarez, Sonia. 1998. `Latin American Feminisms "Go Global": Trends of the 1990s and

Challenges for the New Millenium', in Alvarez, Sonia, Evelina Dagnino, and

Arturo Escobar (eds.), Cultures of Politics/Politics of Cultures: Revisioning Latin-

American Social Movements. Boulder: Westview. Pp. 293-324.

Alvarez, Sonia. 2000. 'Translating the Global: Effects of Transnational Organising on

Local Feminist Discourses and Practices in Latin America'. Meridians: Feminism,

Race, Transnationalism, Vol. 1 (November).

111

Alvarez, Sonia, Nalu Faria and Miriam Nobre (eds). 2003. Dossi Feminismos e Frum

Social Mundial (Dossier on the World Social Forum), Estudios Feministas

(Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, Brazil), Vol. 11, No. 2, pp.

533-660. www.scielo.br/ref.

Barrig, Maruja. 2001. Latin American Feminism: Gains, Losses and Hard Times,

NACLA Report on the Americas, Vol. 34, No. 5, pp. 29-35.

Barton, Carol. 2004. Global Womens Movements, Socialism and Democracy, No. 36,

pp. 151-84. http://www.sdonline.org/35/globalwomensmovements.htm.

Bernard, J essie. 1987. The Female World from a Global Perspective. Bloomington:

Indiana University Press. 287 pp.

Brenner, J ohanna. 2003. Transnational Feminism and the Struggle for Global J ustice,

New Politics (New York), Vol. 9, No. 2.

Brenner, J ohanna. 2004. Transnational Feminism and the Struggle for Global J ustice

(abbreviated), in J ai Sen et. al. (eds), The World Social Forum: Challenging

Empires. New Delhi: Viveka. Pp. 25-34.

Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cahiers de la femme. 2002. Women, Globalisation and

International Trade (Special Issue), Vols. 21-2, Nos. 4/1.

Charkiewicz, Ewa. 2004a. Global Bio-politics and Corporations as the New Subject of

History. (Unpublished draft).

Charkiewicz Ewa. 2004b. Beyond Good and Evil: Notes on Global Feminist Advocacy,

Women in Action. http://www.isiswomen.org/pub/wia/wia2-04/ewa.htm.

Dickenson, Donna. 1997. 'Counting Women in: Globalisation, Democratisation and the

Women's Movement', in Anthony McGrew (ed), The Transformation of

Democracy? Globalisation and Territorial Democracy. Cambridge: Polity. Pp. 97-

120.

Enloe, Cynthia. 2002. Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of

International Politics Updated Edition with a New Preface. Berkeley: California

University Press.

Eisenstein, Hester. 2004. Globalisation and Gender: Marxist-Feminist Perspectives,

Socialism and Democracy, No. 36, pp. 1-6.

http://www.sdonline.org/35/Introductiongender.htm.

Eisenstein, Zillah. 1998. Global Obscenities: Patriarchy, Capitalism, and the Lure of

Cyberfantasy. New York: New York University Press.

Eschle. Catherine. 1999. 'Building Global Visions: Democracy and Solidarity in the

Globalisation of Feminism', International Feminist Journal of Politics. Vol. 1, pp.

327-31.

Eschle, Catherine. 2001. Global Democracy, Social Movements, and Feminism.

Boulder: Westview. 278 pp.

Eschle, Catherine. 2003. Skeleton Women: Feminism and Social Movement:

Resistances to Corporate Power and Neoliberalism. University of Strathclyde.

Unpublished.

Eschle, Catherine and Neil Stammers. 2004. 'Taking Part: Social Movements, INGOs

and Global Change' in Alternatives, Vol. 29, No. 3.

Facio, Alda. 2003. Globalizacin y Feminismo (Globalisation and Feminism)

http://www.whrnet.org/docs/perspectiva-facio-0302.html.

Findlay, Tammy. 2004. Getting Our Act Together: Gender, Globalisation, and the State,

Socialism and Democracy, No. 36, pp. 43-84.

http://www.sdonline.org/35/gettingouracttogether.htm.

Grant, Rebecca and Kathleen Newland (eds). Gender and International Relations. 1991.

Milton Keynes: Open University Press. 176pp.

112

Harcourt, Wendy (ed). 1999. Women@Internet: Creating New Cultures in Cyberspace.

London: Zed. 240 pp.

Harcourt, Wendy. 2001. 'Globalisation, Women and the Politics of Place: Work in

Progress', Paper to EADI Gender Workshop: Gender and Globalization:

Processes of Social and Economic Restructuring, April 20 2000.

Kemapadoo, Kamala and J o Doezema (eds). 1998. Global Sex Workers: Rights,

Resistance, and Redefinition. New York and London: Routledge. 294 pp.

Lorde, Audre. (1984). The Masters Tools Will Never Dismantle the Masters House. In

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Santa Cruz, CA: The Crossing Press. Pp.

110-113.

Mendoza, Breny. 2001. 'Conceptualising Transnational Feminism'. Paper to Conference

on 'Trends in Transnational Feminisms', Institute of Gender, Globalisation and

Democracy, California State University, Northridge. J une 13. 11 pp.

Miles, Angela. 1996. Integrative Feminisms: Building Global Visions, 1960s-1990s.

London: Routledge.

NextGENDERation Network. 2004. Refusing to Be The Womens QuestionEmbodied

Practices of a Feminist Intervention at the European Social Forum 2003,

Feminist Review, No 27, pp. 141-151.

Olea Maulen, Cecilia (ed). 1998. Encuentros, (des)encuentros y bsquedas: el

movimiento feminista en Amrica Latina. Lima: Flora Tristn. 234 pp.

Peterson, Spike. 1992. Gendered States: Feminist (Re)Visions of International Relations

Theory. Boulder: Lynne Reiner.

Pettman, J an J indy. 1996. Worlding Women: A Feminist International Politics. London:

Routledge.

Sanchs, Norma (ed). 2001. El ALCA en debate: Una perspectiva desde las mujeres.

[The FTAA in Debate: A Women's Perspective]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Biblos.

195 pp.

Sylvester, Christine. 2002. Feminist International Relations: An Unfinished Journey.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thayer, Millie. 2001. 'Transnational Feminism: Reading J oan Scott in the Brazilian

Serto', Ethnography, No. 4, J une.

Tickner, Ann. 2005. Feminist Perspectives on International Relations, in Walter

Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse and Beth Simmons (eds), Handbook of International

Relations. London: Sage. Pp. 275-91.

Vargas, Virginia. 1992. Women: Tragic Encounters with the Left, NACLA Report on the

Americas, Vol. 25, No. 5, pp. 30-34.

Vargas, Virginia. 1996. International Feminist Networking and Solidarity Toward the VII

Latin American and Caribbean Feminist Gathering Chile, 1996, Occasional

Paper, No. 9, Grabels: Women Living Under Muslim Laws.

http://www.wluml.org/english/pubs/pdf/occpaper/OCP-09.pdf.

Vargas, Gina. 1999. 'Ciudadanias globales y sociedades civiles. Pistas para la anlisis'

[Global Citizenships and Civil Societies: Lines for Analysis], Nueva Sociedad, No.

163, pp. 125-38.

Vargas, Virginia. 2001. 'Ciudadana y globalizacin: hacia una nueva agenda global de

los movimientos feministas' [Citizenship and Globalisation: Towards a New

Global Agenda for the Feminist Movements] in Norma Sanchs (ed). El ALCA en

debate: Una perspectiva desde las mujeres. Buenos Aires: Editorial Biblos. Pp.

61-76.

Vargas, Virginia. 2003. Feminism, Globalisation and the Global J ustice and Solidarity

Movement, Cultural Studies, Vol. 17, No. 6, pp. 905-20.

113

Waterman, Peter and J ill Timms. 2004. Trade Union Internationalism and A Global Civil

Society in the Making, in Kaldor, Mary, Helmut Anheier and Marlies Glasius

(eds), Global Civil Society 2004/5. London: Sage. Pp. 178-202.

Waterman, Peter. 1998/2001. Globalisation, Social Movements and the New

Internationalisms. London: Mansell/Continuum. 302 pp.

Waterman, Peter. 1999a. 'Women as Internationalists: Breaching the Great Wall of

China' (Review Essay), International Feminist Journal of Politics, Vol. 1, No. 3,

pp. 490-97.

Waterman, Peter. 1999b. 'The Brave New World of Manuel Castells: What on Earth (or

in the Ether) is going on?' (Review of Vols. 1-3 of `The Information Age:

Economy, Society and Culture'), Development and Change. Pp. 357-80.

Wichterich, Christa. 2000. The Globalised Woman: Reports from a Future of Inequality.

London: Zed. 180 pp.

Yuval-Davis (2004), Womens/Human Rights and Feminist Transversal Politics

http://www.bristol.ac.uk/sociology/ethnicitycitizenship/nyd2.pdf. Forthcoming in

Myra Marx Feree and Ailli Tripp (eds), Transnational Feminisms: Womens

Global Activism and Human Rights. New York: New York University Press.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Lepsl 530 Third Party Doctrine and Csli AnalysisDokument4 SeitenLepsl 530 Third Party Doctrine and Csli Analysisapi-462898831Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Shuffledwords PDFDokument279 SeitenShuffledwords PDFHarvey SpectarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- To Sir With Love - Movie AnalysisDokument8 SeitenTo Sir With Love - Movie Analysismonikaskumar_2708312Noch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Death Certificate FormDokument3 SeitenDeath Certificate FormMumtahina ZimeenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Marketing Case Study-Southwest Airlines Write-UpDokument7 SeitenMarketing Case Study-Southwest Airlines Write-UpShardonay ReneeNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Mental Health Nursing Assignment Sample: WWW - Newessays.co - UkDokument15 SeitenMental Health Nursing Assignment Sample: WWW - Newessays.co - UkAriadne MangondatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA - Stoics and Stoic Philosophy PDFDokument3 SeitenCATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA - Stoics and Stoic Philosophy PDFBuzzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Prepared by Nesi Zakuta: Dogus University Industial Enginering FacultyDokument24 SeitenPrepared by Nesi Zakuta: Dogus University Industial Enginering FacultySibel Bajram100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Restriction On Advocates To Take Up Other Employments: Dr. Haniraj L. Chulani vs. Bar Council of Maharashtra & GoaDokument3 SeitenRestriction On Advocates To Take Up Other Employments: Dr. Haniraj L. Chulani vs. Bar Council of Maharashtra & GoaGaurab GhoshNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Cyber Bullying ScriptDokument3 SeitenCyber Bullying ScriptMonica Eguillion100% (1)

- Lawyers Cooperative Publishing Co. v. TaboraDokument3 SeitenLawyers Cooperative Publishing Co. v. TaboraMico Maagma CarpioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- 1 Estate of Hemady v. Luzon SuretyDokument2 Seiten1 Estate of Hemady v. Luzon SuretyTherese EspinosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Success - Plan of VestigeDokument16 SeitenSuccess - Plan of VestigeCHARINoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Philo12 q1 w1-2 APILDokument27 SeitenPhilo12 q1 w1-2 APILJoiemmy GayudanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Regulatory Framework AND Legal Issues IN Business: Cristine G. Policarpio Bsais 3-BDokument33 SeitenRegulatory Framework AND Legal Issues IN Business: Cristine G. Policarpio Bsais 3-BApril Joy SevillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- XI-Poem 1 Ms AmmaraDokument10 SeitenXI-Poem 1 Ms AmmaraAmmara KhalidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shahnama 09 FirduoftDokument426 SeitenShahnama 09 FirduoftScott KennedyNoch keine Bewertungen

- State - CIF - Parent - Handbook - I - Understanding - Transfer - Elgibility - August - 2021-11 (Dragged) PDFDokument1 SeiteState - CIF - Parent - Handbook - I - Understanding - Transfer - Elgibility - August - 2021-11 (Dragged) PDFDaved BenefieldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Modern InventionDokument2 SeitenModern InventionLiah CalderonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- b00105047 Posthuman Essay 2010Dokument14 Seitenb00105047 Posthuman Essay 2010Scott Brazil0% (1)

- Accuracy of Eye Witness TestimonyDokument5 SeitenAccuracy of Eye Witness Testimonyaniket chaudhary100% (1)

- Kenneth L. Kusmer - Down and Out, On The Road - The Homeless in American History (2003) PDFDokument345 SeitenKenneth L. Kusmer - Down and Out, On The Road - The Homeless in American History (2003) PDFGiovanna CinacchiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Making A Reaction StatementDokument6 SeitenMaking A Reaction StatementKharisma AnastasisNoch keine Bewertungen