Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Art:10.1007/s11125 012 9231 0

Hochgeladen von

Colton McKee0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

23 Ansichten16 Seitenk

Originaltitel

art%3A10.1007%2Fs11125-012-9231-0

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenk

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

23 Ansichten16 SeitenArt:10.1007/s11125 012 9231 0

Hochgeladen von

Colton McKeek

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 16

OPEN FI LE

Racial and ethnic diversity in schools: The case of English

Canada

Diane Gerin-Lajoie

Published online: 8 June 2012

UNESCO IBE 2012

Abstract In recent decades, schools located in English Canada have experienced

important demographic changes in their student population. This article examines the

racial, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural diversity in these schools, through the discourses of

those who spend the most time with the students: teachers and principals. Here, the concept

of discourse is understood as a way of framing the world; it is far more than a simple tool

for communicating with others. Since education operates under provincial and territorial

jurisdiction in Canada, these discourses are examined in the context of provincial school

policies that specically address the issue of diversity among students. Using qualitative

data collected in a national study completed in 2007, the analysis shows how teachers and/

or principals make sense of this changed reality in their schools and its impact on their

daily work.

Keywords Racial and ethnic diversity Canada Multicultural education

In Canada, racial and ethnic diversity has been the reality for decades. Canadas three

major metropolitan areasMontreal, Toronto, and Vancouverhost considerable num-

bers of newcomers every year. According to the 2006 census, these three areas combined

received 68.9 % of the immigrant population coming to Canada. In the metropolitan areas

of Montreal and Toronto, a majority of the newcomers settled rst in the core cities of

Montreal (76.3 %) and Toronto (59.8 %). The situation in Metropolitan Vancouver was

slightly different: 74.7 % of newcomers settled in a more dispersed pattern across four

municipalities, those of Vancouver, Richmond, Burnaby, and Surrey.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, in response to an already increasingly diverse racial

and ethnic population, schools needed to adapt to the changing social context of the

communities that they serve. As the late Canadian sociologist Helen Harper (1997) pointed

My sincere thanks go to my colleague and friend Stephen Anderson for his invaluable comments on the rst

and second versions of this article.

D. Gerin-Lajoie (&)

OISE, University of Toronto, 252 Bloor Street West, Toronto, ON, Canada

e-mail: diane.gerin.lajoie@utoronto.ca

1 3

Prospects (2012) 42:205220

DOI 10.1007/s11125-012-9231-0

out, schools are expected to meet the needs of a population that is racially, culturally and

linguistically diverse, to confront gender, racial and economic disparity and discrimina-

tion (p. 192). Administrators in the Canadian school system took multiple measures to

accommodate immigrant students and to integrate them into the public schools. Now in the

early twenty-rst century, after more than 30 years of the school system adapting to an

increasing racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity, how do teachers and principals com-

prehend the classroom reality? What do they say about students racial and ethnic diversity

in English Canadian schools? In this article, I discuss ndings from a pan-Canadian

investigation on the evolution of Canadian school personnel through school reforms. A

section of this study examines teachers and principals discourses about racial and ethnic

diversity in their schools. In particular, I examine how Canadian school personnel make

sense of the racial, ethnic, and linguistic reality of the classroom, and most importantly,

how these teachers and principals think this diversity impacts their work on a daily basis.

(Note that here I do not address the discourse of those teachers and principals working in

the French-speaking province of Quebec).

Since education operates under provincial and territorial jurisdiction in Canada, I

examine these discourses in the context of provincial school policies that specically

address the issue of diversity among students. I use a notion of discourse that extends

beyond simple talking and speaking practices. Social reality is always shaped by dis-

courses that in turn come to inuence individuals social interactions (Gerin-Lajoie 2008).

In choosing to work from the notion of discourse, I have tried to avoid the use of a

positivist framework that tends to emphasize notions of attitudes and measures when

looking at the ways teachers and principals make sense of their work. I hold that the

working experiences as described by school personnel cannot be discussed within a pre-

scriptive framework that does not allow for a thorough analysis of individual views on

students diversity. To illustrate how contemporary Canadian teachers and principals

comprehend diversity in their schools, I use results from a 5-year (20022007) pan-

Canadian study funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of

Canada (SSHRC) through its Major Collaborative Research Initiatives programme.

Context

Before focusing explicitly on schools and diversity in English Canada, it is important to

describe how Canadas federal government began, over four decades ago, to respond to issues

of growing diversity as a result of changing immigration policies and demographic patterns; it

introduced multiculturalism well before any of the provinces or territories. Canada has long

been recognized as a country of immigrants, but in the years just after World War II, it

witnessed a signicant increase. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Canada became more and

more racially and ethnically diverse, initially because of an inux of immigrants fromEurope,

and later after relaxed immigration laws opened the door to non-European newcomers from

developing world countries that contributed to growth in racial and linguistic diversity. Gosh

(2011) points out that Whereas in 1971, about 62 % immigrants came from Europe, in 2006

as much as 58 % immigrants came from Asia (including the middle East) (p. 5).

At the same time, the country was going through challenging political times, due in part

to the rise of nationalism in Quebec, through a political movement referred to as the Quiet

Revolution. That movement embodied the desire among Quebecs Francophone majority

to assert political and economic control over its own destiny, and to become matres chez-

nous (masters in our own house). To address the concerns voiced by Francophones in

206 D. Gerin-Lajoie

1 3

Quebec, the federal Liberal government of Pierre Elliot Trudeau set up the Royal Com-

mission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism at the end of the 1960s. Its mandate was to look

into linguistic and cultural issues in the country. However, the discussions held in the

public hearing sessions, or audiences, went beyond the relationships between Quebec and

English Canada. The Commissions recommendations resulted in a federal policy on

ofcial bilingualism in Canada that excluded any reference to biculturalism. However,

people with origins other than French or English who took part in the audiences became

increasingly vocal about the fact that other cultures played roles in the Canadian mosaic,

roles that also deserved recognition. As a result, a recommendation was made to

acknowledge and support the presence of all cultures within Canadian society.

In 1971, the federal government announced its policy of multiculturalism within a

bilingual framework; it soon became the rst country in the world to adopt an ofcial

policy on multiculturalism, called the Multiculturalism Policy of Canada (Ministry of

Justice 1971). Through these actions, the federal government recognized the value of all

Canadian citizens regardless of their racial or ethnic background, their language, or their

religion. It also recognized the rights of Aboriginal peoples and the status of our two

ofcial languages, English and French. The 1971 policy contained four themes. The federal

government would: (1) assist cultural groups in retaining and fostering their identity; (2)

assist members of all cultural groups to overcome cultural barriers to full participation in

Canadian society; (3) promote creative encounters and interchange among all Canadian

cultural groups in the interest of national unity; and (4) continue to assist immigrants to

acquire at least one of the two ofcial languages.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the federal policy position evolved largely because of

difculties encountered in the area of race relations. With an increasing number of non-White

immigrants, racism became more overt. Anti-discrimination programmes were soon intro-

duced. In 1982, multiculturalism was included in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Free-

doms (Section 27). In 1988, the policy on multiculturalism became a federal law. The

Canadian Multicultural Act (Bill C-93) reafrmed multiculturalismas a basic characteristic of

the Canadian society. The ofcial discourse was still about cultural retention (as in the policy

of 1971), but an additional dimensionsocial equalitywas incorporated into the law.

The 1971 policy on multiculturalism was under federal jurisdiction. Over the next two

decades, the governments of Canadas 10 provinces and 3 territories developed their own

provincial or territorial policies in response to the increasing racial, cultural, and linguistic

heterogeneity in their respective contexts. In 1974, Saskatchewan became the rst province

to adopt legislation on multiculturalism, with the Saskatchewan Multiculturalism Act; in

1997, a new Act was passed in response to issues of social justice such as racism and

discrimination. In 1984, Manitoba adopted the Manitoba Intercultural Council Act. The same

year, Albertas Cultural Heritage Act came into effect, to be superseded in 1996 by the

Human Rights, Citizenship and Multiculturalism Act. In Ontario, an ofcial multicultural

policy was adopted in 1977, which became law in 1982. In Quebec, policy makers chose to

speak in terms of interculturalism, rather than multiculturalism, placing greater emphasis on

intercultural communication and relations than on cultural retention. The government of

Quebec rst adopted an ofcial policy in 1981. In Nova Scotia, the Act to Promote and

Preserve Multiculturalism was promulgated in 1989. New Brunswick introduced its policy

on multiculturalism in 1986. In Prince Edward Island, a multiculturalism policy was adopted

in 1988. The province of British Columbia adopted its Multiculturalism Act in 1993. As of

today, the province of Newfoundland and Labrador has yet to adopt a formal multicultur-

alism policy, though the governments position has been vetted in a discussion paper that

addresses the issue of diversity and how public institutions should respond.

Racial and ethnic diversity in schools 207

1 3

In Canada, the area of education is under provincial and territorial jurisdiction.

Throughout the country, some local school board and district authorities made efforts to

adopt and implement policies specically focused on growing ethnic and racial diversity,

as early as 1975, even before the provinces promulgated any ofcial policy (Anderson and

Fullan 1985). School boards and school districts developed their own guidelines and/or

policies. In other words, students diversity was recognized as a reality and some school

boards, especially those located in urban settings, made it a priority to nd ways of

responding to the particular needs of newcomer students and of integrating all their stu-

dents into the schools and education programmes and services. Although Canada still

experiences a large inux of immigrants annually from many regions of the world, and

ethnic and racial diversity remain a challenging characteristic of the communities served

by many schools across the country, the issue of students diversity became less of a

political priority at the end of the twentieth century. As our study results show, the

dominant ofcial discourse in public education now focuses mostly on ideologies and

policies that address three specic areas: governance, accountability, and the profession-

alization of teachers. Nevertheless, the topic of diversity remains present in teachers and

principals discourses, even though it does not take centre stage as it did in the preceding

decades in the ofcial government discourse and specic policies.

Ofcial discourse on diversity

Before going further, let me also note briey that I understand the notion of discourse as far

more than a simple tool for communicating with others. Around the 1960s, some critical

theorists began to understand the term philosophically, as a social construct. For them,

language was not only a vehicle of communication, but reected the way people think, and

those ways of thinking were themselves inuenced by prevailing social practices.

Discourse can be dened as a regulated system of meanings and representations (James-

Wilson 2007). As Foucault (1972) argued, discourse is a regulated practice. Power

becomes a key element in the deconstruction of the notion of discourse. From Foucaults

point of view, power is sifted through social practices, which then produce possible forms

of behaviour, as well as restricting others. Consequently, discourses shape the way that

people think and interact. Meanings are inuenced by history, within which social prac-

tices are nested. As Niesz (2006) explains:

[] while discourses are often shared within and across communities, they are also

linked to particular historical moments, and they represent interests that are political

in nature. Moreover, discourses are not static across time, they are always in com-

petition with contradictory discourses, and, in fact, constitute cultural resources that

are used in diverse ways by local agents situated in particular social contexts. (p.

337)

The teachers and principals who participated in our study seemed to share a common

discourse, one aligned mostly with the ofcial discourse in their own provincial contexts.

The notion of difference

When we examine the ofcial discourse on diversity, we conclude that, over the years,

diversity has been mostly understood in terms of differences; policy responses to dif-

ferences have taken several forms over the years (Gerin-Lajoie 2008). Harper (1997)

208 D. Gerin-Lajoie

1 3

identied ve historical responses to the notion of difference, which she named as sup-

pressing difference, insisting on difference, denying difference, inviting difference, and

critiquing difference.

Suppressing difference. This response aims to assimilate subordinate groups into the

dominant group through the suppression of the former groups cultures and/or

languages. In Canada, this has historically been the case, for example, for First Nations

peoples and for Francophones outside of Quebec. This response intended to create

uniformity within the Canadian population. This response is also implicitly present

today, when schools make efforts to assimilate students to the dominant school culture

(Solomon and Levine-Rasky 2003).

Insisting on difference. Recognizing that differences are natural, this response

emphasizes the need for accommodation. The notions of separation and segregation

become part of the ofcial discourse. Historically, women, Blacks, and people with

disabilities have been marginalized within this approach, which was prevalent at the

end of the nineteenth and the early twentieth century. Nowadays, the segregated

movement has returned in some situations. For example, some education stakeholder

groups perceive all-Black schools or all-girls schools as a way to alter power relations

and enhance opportunities for disadvantaged students to excel in schools. This recent

call for voluntary segregation, however, stands in contrast to the movement of imposed

segregation that the country experienced at the turn of the twentieth century.

Denying difference. This response minimizes rather than highlights differences among

students. This approach is associated with the popular notion of meritocracy, which

emphasizes that success is an individual responsibility, and that with hard work and

perseverance, anyone can succeed. This liberal perspective emphasizes the need to

create equal opportunity. Denying difference is a notion that was salient in the 1960s.

Again, it is possible to argue that this response to difference has returned, albeit in a

different form. In the accountability context in which school personnel and students

currently live, expectations are that all students will attain common performance

standards, as measured by government standardized tests, regardless of the students

background, past performance, and social reality. In this instance, policy makers are

seeking to redress inequality and reduce inequities in educational performance by

holding all students to common learning expectations. Notions such as colour-blindness

and sameness can be associated with this particular view on the notion of difference.

Inviting difference. This response is concerned with celebrating diversity. It is more

about tolerance than about change. Canada is commonly perceived as a mosaic,

composed of a variety of ethnic groups, which have their own cultural traditions that need

to be acknowledged by the host country. This approach invokes a folkloric notion of

culture. In the 1970s and 1980s, this response was manifested in multicultural education

policies embraced by most provincial and territorial ministries of education. It remains

very much part of the current educational discourse at all levels of the education system.

Critiquing difference. This response recognizes and aims to understand power relations.

How and when difference is produced becomes the focus of inquiry. Antiracist

education is the best-known example of this type of critical inquiry. It examines

prejudices and systemic discrimination and emphasizes that the way society is

structured limits some students while placing others at an advantage (Gerin-Lajoie

2008). The ultimate aim is to alter those relations to create a more equitable distribution

of power and control over public institutions and the social and economic benets

associated with participation in those institutions.

Racial and ethnic diversity in schools 209

1 3

These ve lenses underlie specic types of policies and/or guiding principles. The

literature refers to three main perspectives when it comes to recognition of diversity in

schools. These are multicultural education, intercultural education, and anti-racist educa-

tion. In Canada, multicultural education is present mostly in English-speaking provinces

and intercultural education in Quebec. Anti-racist education has been, to some extent, part

of the ofcial discourse in Ontario since the early 1990s, though the governments ofcial

position has wavered depending on the provincial political party in power (e.g., New

Democrats, Liberals, Conservatives). In the following section, I briey describe those three

discourses.

Multicultural education

As previously mentioned, in English Canada the multicultural education perspective has

been part of the ofcial discourse on the classroom integration of students from diverse racial

and ethnic origins since the 1970s. Based on the principles established in the federal Mul-

ticulturalism Act, this perspective portrays Canada as a cultural mosaic; each minority group

contributes to the making of the Canadian society, where all cultures deserve equal recog-

nition. In the context of the school, students from diverse racial and ethnic origins must be

treated with respect. Multicultural education values and celebrates differences among stu-

dents in emphasizing folkloric artifacts such as music and food, which corresponds to

Harpers (1997) notion of inviting difference. However, if we look back in time, the

notion of multicultural education was at some point described as potentially transformative

and a means of seeking social justice, especially in the educational context of the United

States (Banks 2004). Over time, this critical notion has evolved to be understood more as a

celebratory practice than as a transformative one, but some confusion about the denition

remains among scholars (Jones 2000). This is not a new debate, though: In the early 1990s,

concerns were raised about the fact that the term multicultural education was often

interpreted in a variety of ways. Tator and Henry (1991) describe this variety:

There is enormous confusion and ambiguity in the language which is used, as well as

a lack of clarity with respect to the signicant distinction, which underlies the words.

The vocabulary includes the labels of multiculturalism, intercultural and cross-cul-

tural education, race relations, racial and ethnocultural equity, and antiracist edu-

cation. (p. 12)

Beside its obscure denition, more recent critiques have also focused on the common

food and festivals approach to multicultural education (Knight 2008; Ruitenberg 2011;

Shaikh 2006; Sleeter 2004). The critics argue that this is a supercial way to acknowledge

diversity among students, in part because it is unrealistic to think of all cultures as being

equal. From this point of view, the relationship between the dominant culture of the host

society and that of minorities must be understood in terms of power relations, where

inequalities persist despite the ofcial discourse of equality. To be equal, minorities would

need to have access to political and economic power, which they typically do not have. In

conclusion, multicultural education is viewed as being assimilationist overall in its

approach to diversity in the public education system.

Intercultural education

This second type, found in the province of Quebec, emphasizes the importance of putting

in place a dialogue between cultures and integrating the newcomers into the host society, in

210 D. Gerin-Lajoie

1 3

order to include them in the project of a societe nouvelle, in which they would be able to

participate fully.

Ouellet (1986) denes intercultural education as aiming at specic knowledge and

attitudes:

The systemic effort towards the development, among members of the majority

groups as well as minority groups, of a better understanding of the various cultures, a

greater capacity to communicate with persons of other cultures, and more positive

attitudes towards the various cultural groups of society. (p. 16)

In the context of this intercultural education perspective, Quebec insists on the importance

of collective rights, in contrast with the multicultural education perspective that takes an

individualistic approach to the notion of culture. One critique made of the intercultural

education approach is that it is still very assimilationist, because the host culture dominates

in this discourse. In schools, for example, the values of the host society are transmitted to

the students. The ofcial discourse in Quebec, for example, insists on the importance of a

common Quebecois culture, without leaving much room to the other cultures. Like the

multicultural education perspective, intercultural education does not denounce the fact that

members of minority groups are not structurally integrated, especially in the economic

sphere.

Critics of intercultural education see it as assimilative in nature, like multicultural

education. If the intention is to establish more equitable social relations between new-

comers and the host society, intercultural education in its present form is far from attaining

this objective (Ghosh et al. 1995). As Jacquet (2008) explains, the ambiguity surrounding

this concept and contradictory educational practices conducted under the umbrella of

intercultural education led to pitfalls similar to those attributed to multicultural education

(p. 60).

Antiracist education

Antiracist education is a critical approach that examines how schools support racism. This

discourse emerged as a critique of multicultural education (Sleeter and Delgado-Bernal

2004). From the antiracist perspective, economic inequalities must be abolished if our

society is to fully integrate minorities. In education, racial and ethnic groups may need to

be treated differently, not equally, in order to achieve equity in the host society and in its

schools. Schools must go beyond simply celebrating differences, to placing issues of equity

and social justice squarely on the agenda. As it stands now, schools do not respond

adequately to the needs of their racially, ethnically, linguistically, and culturally diverse

student populations (Connelly 2008; Gerin-Lajoie 2008). This critical discourse is far from

new. It was already in use two decades ago, as illustrated in the following comment, still

very accurate, made by van Dijk (1993):

Antiracist views hold that lacking access to quality schools, discrimination in the

classroom, stereotyping in textbooks, and a host of other factors lead to a position of

minority children at school that is usually described as disadvantaged, but in

reality reects their subordinate position. (p. 200)

Though van Dijks comment is not recent, it captures the essence of antiracist education.

Scholarship published since then on antiracist education emphasizes the need to look

closely at how the school system perpetuates the social order and how power relations are

reproduced, for instance, in terms of who is integrating whom, and to what structures (King

Racial and ethnic diversity in schools 211

1 3

2004; Sleeter 2004). As described by Dei (2011), anti-racism education is involved with

learning about the experiences of living with racialized identities and understanding how

students lived experiences in and out of school are implicated in youth engagement and

disengagement from school (p. 17). From this perspective, on one hand, schools convey

liberal values concerned with tolerance and respect. On the other hand, differential

treatment based on racial, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds is also present in schools and

can lead to potential discrimination (Henry and Tator 1999, p. 90). The existing ofcial

discourse does not acknowledge the impact of race and ethnicity on the students lived

experiences both in and outside of the school. Antiracist education is about social justice.

In Ontario, in the early 1990s, the New Democratic Party (NDP) led Canadas rst

attempt to implement an antiracist education framework. When it rst came into power, the

NDP government established an Anti-Racism Unit within the Education Ministry. In 1993,

the provincial government published a set of guidelines and mandated the development of

policies on antiracism and ethnocultural equity in Ontario school boards. The document

stated:

Antiracism and ethnocultural equity school board policies reect a commitment to

the elimination of racism within schools and in society at large. Such policies are

based on the recognition that some existing policies, procedures, and practices in the

school system are racist in their impact, if not their intent, and that they limit the

opportunity of students and staff belonging to Aboriginal and racial and ethnocul-

tural groups to fulll their potential and to maximize their contribution to society.

(Ontario Ministry of Education and Training 1993, p. 5)

The objective of this policy was to go beyond the simple celebration of differences

between students from diverse racial and ethnic origins. This type of policy called for a

critical examination of school practices by school personnel as well as by students,

representing a language of possibilities (Gerin-Lajoie 1995). In 1995, however, the NDP

lost power to a Conservative government that did not support the NDPs anti-racist agenda.

The Anti-Racism unit was abolished and further government action on that policy agenda

was suspended. In 2001, the Conservatives lost control of the Ontario government to the

Liberal Party. In 2007, the Liberal government reworked the NDP guidelines of 1993.

Taking a milder tone, the ofcial discourse does not talk about antiracism as such, but

rather about inclusiveness, without emphasizing the notion of power in its discourse.

It is time now to examine how contemporary educators are making sense of diversity in

their classrooms. Let me rst introduce the study.

Methodology

The ndings I examine here are drawn from a large-scale pan-Canadian study of teachers

and school principals working in the publicly funded school system. The aim of the study,

called Current Trends in the Evolution of School Personnel in Canadian Elementary and

Secondary Schools, was to examine the school practices of personnel in both elementary

and secondary schools, and to investigate their working conditions. Researchers from 16

Canadian universities participated in this longitudinal study. The study focused on four

main areas: (a) the working conditions of the teaching personnel, (b) the impact of edu-

cation reforms and policies on school principals and teachers, (c) the training and pro-

fessionalization of teaching personnel, and (d) the transformation of pedagogical practices.

The overall study was made up of four separate projects. Project 1 created a national

212 D. Gerin-Lajoie

1 3

statistics database. Project 2 created a national policy documentary database. Project 3 was

a survey of teachers and school principals about their school practices. Project 4 was a

longitudinal qualitative study of teachers and school principals and their school practices.

Beside my role as co-director of the research activities taking place across the country, I

was involved more specically in Project 4, in the design of the qualitative study (ques-

tionnaires and interviews guidelines), the conduct of the interviews and the analysis of the

results.

Four major ndings emerged from our overall analysis. The participants reported that

governance, accountability, the professionalization of teachers, and the diversity of school

populations were the factors that had the most impact on their work, even though that

diversity was a lower priority for educational policy makers than it had been in the

preceding decades.

The results I discuss here are from Project 4 only; I focus on the school personnels

responses to the diversity in school populations, our fourth eld of analysis. This sub-study

looked closely at how teachers and principals made sense of their work and of the diverse

reforms and policies that inuence this work. Through yearly questionnaires and, most

importantly, with the use of interviews, the study sought to highlight the discourse of these

teachers and principals about their school practices in their particular policy and demo-

graphic contexts. Over a period of 5 years, the 10 members of the research team working

on Project 4 followed a cohort of 500 participants, including a total of 300 teachers and

principals, 100 each from Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal. The other 200 participants

were from Halifax, Moncton, Winnipeg, and Saskatoon. Annual questionnaires were

administered to all 500 participants. In addition, the 300 participants from Vancouver,

Toronto, and Montreal participated in two individual interviews during the course of the

study. The yearly questionnaires addressed ve issues. For year 1 the issue was the impact

of social change and education policy reform. For year 2 it was professional practices and

for year 3, professional knowledge and prociency. For year 4 it was interactions with

other social actors. The year 5 questionnaires followed up on some issues raised in the

previous questionnaires. The interviews also had different yearly foci. Those in the rst

year focused on the career paths of school personnel, and those in the second year asked

them to discuss the impact of school policies and reforms on teachers and principals work,

including those associated with student diversity.

To ensure that our results would address the same issues, we used the same interview

guidelines across the country. The signicant number of interviewers involved in Project 4

across Canada called for a systematic approach when doing the interviews. I report only

the ndings from the interviews.

Findings

Among the ndings, three are of particular interest. The participants discourse on diversity

emphasized: (a) the notion of colour blindness and the individualization of students, (b) the

celebration of differences, and (c) the lack of adequate professional training to work with

students from diverse backgrounds.

Colour blindness and the individualization of students

The teachers and principals who participated in the study typically expressed the view that

they see their students as being all the same, independent of their racial and ethnic origins.

Racial and ethnic diversity in schools 213

1 3

They claim not to differentiate among their students, and to treat everyone equally. Two

samples from interviews illustrate this attitude:

I think most teachers will tell you, youve got a class in front of you, you dont have a

class of Asian kids, you dont have a class of Sri Lankan kids, you dont have a class of

Korean kids, youve got a class of kids, and maybe you have to sometimes sit back and

say, well what backgrounds do you have in there? Well let me think for a second.

The school population is very diversied, but lets say that [] the kids [] we did

not really see, I dont know if this is because I have been in this for some years now,

but me, I do not see really [] there is no difference for me between the kids.

Colour blindness represents a powerful discursive form in educational settings (Gosh 2011;

Knight 2008; Solomon and Levine-Rasky 2003). In our study, the teachers and principals

interviewed sincerely believed that every student should be treated equally. However, as

Solomon and Levine-Rasky (2003) explain, [] colour blindness, when ostensibly a

channel for rectifying educational inequity on the basis of race, guarantees no such

commitment. In fact, it often conceals a teachers interest in perpetuating educational

inequity through an expectation for students to assimilate (p. 22). Other critical scholars,

like Sleeter (2004), see colour-blindness as a myth.

In considering all students as equal, teachers and principals ignore the existence of

power imbalances among the students that favour specic groups of students in terms of

education access, resources, and outcomes.

For example, those students who demonstrate that they have the right cultural capital

face fewer challenges than those who have grown up in a social context foreign to the

schools dominant values (Bourdieu 1991). The former are part of what the ofcial dis-

course describes as the norm. Critical theorists look at the notion of norm from a different

lens. They associate it with White privileges, emphasizing the fact that knowledge is not

neutral and, as a social construct, it reects the values of the White political and economic

majority (King 2004; Knight 2008; Sleeter 2004; Solomon and Levine-Rasky 2003). The

institutional structure of schooling, according to these critics, still excludes students who

have not been brought up with this type of values at home, in particular those from other

racial and ethnic backgrounds. In this particular school context, when teachers deny that

differences exist, they position students as individuals, and their inclusion in the education

mainstream and their academic success or failure as processes that operate independent of

their social background. It becomes the students responsibility to succeed. We are again in

the presence of a discourse of meritocracy (Gerin-Lajoie 2008), notwithstanding the

obvious social context of student diversity in the community and school classrooms.

In the same logic, students are all treated the same except when problems occur.

Then students are differentiated from the rest of the class, but the problem becomes

individualized. For many educators, harmonious social relations with one another are the

key to success. Two participants had the following to say about this logic:

I dont address that [diversity] at all. I go in the class, I teach. And were all there.

We talk. Theres nothing to be said about it [diversity]. One just goes in and does a

regular school day. Because the groups arent ghting, so theres nothing to address.

If groups were ghting, well then thered be something that would have to be dealt

with, but when everyones getting along, you just proceed ahead.

Students are really good. I mean I nd it a really good school here as far as student

behaviour goes. And one of the rugby players on the bus he asked me to mention that

214 D. Gerin-Lajoie

1 3

you dont see any problems among different backgrounds at [school]. Its a diver-

sied school, and it really seems like everyone gets along, and everyone is very

accepting of other cultures and backgrounds, and I think its a very good school.

Very multicultural, and there doesnt seem to be any racial conict whatsoever []

Ive never seen any racial issues in any of my classes, the kids really just get along

and they really dont care about skin colour. It doesnt matter to them.

Similarly, Solomon and Levine-Rasky (2003) noted that teachers tended to ignore racism

except when it was manifesting itself in physical or verbal attacks. Even then, incidents

still seem to be perceived as individual events, rather than a systemic phenomenon (Gerin-

Lajoie 2008).

Celebration of differences

The traditional principles of celebratory multicultural education are present in the dis-

course of many of the teachers and principals interviewed in the study. This is the lens

through which they perceive students integration in the school. They report that they care

deeply for the minority students, and they believe that sharing cultural symbols and values

is the way to integrate students. In their view, this is the core of multicultural education.

Its a celebration of our diversity and a sharing of each others cultures. Theres a

great two-way street of learning from the students; as well as not just being the

teacher, sometimes youre the student as well.

I think we try to assimilate them into Canadian culture as much as possible, and treat

them fairly and equitably. I think we do, like this week for example, were cele-

brating multicultural education and by having every day a different nationality have

some displays. During lunchtime we have games you know coming from different

ethnic backgrounds here during lunchtime. We pray in different languages. This

week every day we have students praying in their own language. We talk about

diverse cultures. Every year we do something different. Some years here they had

multicultural night when they invited various ethnic groups, dance groups or singers,

or so to put on a show. So in that respect we celebrate our differences by bringing out

the most positive things from various ethnic groups, whether its food or music or so,

we allow them to play their music and share their books and their costumes. You

know to display their costumes, ethnic costumes at lunchtime, so other students can

see.

Well, we acknowledge all the holidays. And theres always an assembly presenta-

tion. We do songs. We do poems. We do books. We do reading activities around all

the cultural celebrations. So, its just really nice.

As I mentioned earlier, this element of the participants discourse is in line with the long-

standing ofcial discourse on multicultural education. This notion of racial, ethnic, and

linguistic integration refers to the celebration of students folkloric origins, using the

foods and festivals concept described by many scholars (Harper 1997; Knight 2008;

Ladson-Billings 1994; Ruitenberg 2011; Shaikh 2006; Sleeter 2004). In the interviews,

they did not question their teaching practices in regards to diversity, although each of the

participants was undoubtedly empathic about the challenges students face as new arrivals

in Canada. They all felt for their students and the challenges they had to get through to

begin a new life in Canada.

Racial and ethnic diversity in schools 215

1 3

Teacher training

Although the ofcial discourse recognizes the presence of a diverse student population in

schools and the importance of meeting their needs, much remains to be done before

teachers will take students diversity into serious consideration, moving their practices

beyond the cultural celebrations noted above (Harper 1997; Jones 2000; Mujawamariya

and Mahrouse 2004). Even in 2011, pre-service teacher training programmes look at

diversity only supercially. Participants spoke out about their need for training to work

with a culturally and racially diversied classroom in a teaching environment with

increasing expectations for accountability (e.g., assessment, reporting) associated with

standards and outcomes-driven curriculum policies (Connelly 2008; Gerin-Lajoie 2008). In

pre-service training, they said, racial and ethnic issues were rarely discussed and they were

rarely expected to reect on educational responses to issues connected to social diversity.

One participant put it this way:

We had a little bit of training, I remember, at some point in time, during a profes-

sional development day, but nothing more than that; this is something you do as it

comes. But, I did not feel any big roadblocks, any big problems. But I think the fact

that we are in a small school helps tremendously. Communications between teachers

is easier. It is easy to go and ask a question.

Those participants who are already teaching in schools reported a general lack of in-service

professional development in this area. Not surprisingly, most of the literature on the issue

reports that teachers are not always well prepared to face the challenge of a racially,

ethnically, and linguistically heterogeneous classroom (Gerin-Lajoie 2002, 2008; Sleeter

2004; Sleeter and Grant 1991; Solomon and Levine-Rasky 1996, 2003). To remedy the

situation, some participants expressed the wish that teachers would be better prepared to

face diversity in the classroom, especially in the area of language and specically in skills

for teaching English as a second language (ESL). Answering a question about the need to

help teachers develop their teaching skills in this area, one teacher said:

Absolutely, and I was just thinking about that when you were saying that, because I

know what I do as an ESL teacher, and this is my rst time teaching ESL since, you

know, 6 years ago. So Im still trying to, you know, learn and get some tricks and get

my bag ready of tricks, and whatever. But the poor kids come to me and they

ounder in other classes because the teachers dont think to give them a vocabulary

list. And Im to blame, too, because I dont do that in my other classes. You just are

so inundated with, you know, the exceptional kids that sometimes the ESL kids are

pushed aside, which is really unfortunate. But I think thats absolutely one of the best

suggestions to do for a faculty, is to make sure that everybody has a rudimentary

understanding and some ESL strategies.

Others felt a less pressing need to develop more expertise in teaching a diverse student

population. These participants felt that even though they were not specically trained to

work with a diversied group of students, they were able to handle it. One teacher

explained:

To me I didnt need to be taught. You know, I had a good handle on different cultures

anyways. Just through work. I mean, you deal with all kinds of different people. And,

so you justit wasnt a stretch for me to nd kids. And it was different for me when

I went to high school. At [large Ontario university], I graduated in 89, and I

216 D. Gerin-Lajoie

1 3

graduated from a school that was probably 95 % white. And still today is predom-

inantly white. And I walk into here where the mix is like Ive never seen before.

Youve got Eastern Europeans, youve got Asians, and Indians, and just the cultural

mix here is something I wouldnt have believed. But I think it really works well.

Still, most participants said they do not have adequate or satisfactory training for working

with racial and ethnic minority students. Our analysis of the interviews led to this conclusion.

Both teachers and principals felt that they were not adequately trained to face the multiracial,

multiethnic, and multilingual classroom. The concerns they raised were mostly about their

role as agents of knowledge transmission within the regulatory milieu and the expectations of

the provincial curriculum. The preoccupations of teachers, in particular, were about how to

ensure that their students could succeed in the context of the provincial school system and its

accountability requirements for student and school performance (Gerin-Lajoie 2008). These

concerns lie within the scope of the ofcial discourse which emphasizes the importance for

schools (students as well as teachers and principals) to be accountable to the general public, a

concept that Ball (2004) refers to as performativity in education (p. 143). Previous studies

echo that conclusion (King 2004; Sleeter 2004).

The results presented above still correspond, for the most part, to existing ndings on

the ways that school personnel think of racial, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural diversity in

the student population. One could conclude that this does not add any substantial

knowledge to what we already know about the ways that students diversity is perceived by

the personnel in English Canada schools. I do not share these views, for two reasons.

The above analysis reiterates the fact that the discourse of our participants is still very

much in line with the ofcial discourse held by provincial and territorial ministries of

education in English Canada. In that discourse, policies are not always clear about how

to achieve the inclusion of all students and assimilation to the majority is still

encouraged, a process which can be described as democratic racism. Principles of

equity and social justice are still absent, for the most part, in school policies and

perspectives on students diversity and the school curriculum in general.

The ndings are also of interest because they refer to a consistent discourse among

school personnel, even though education is under provincial and territorial jurisdiction

in Canada and one could expect some variations both at the policy level and in the ways

that school personnel comprehend the role of the school in the inclusion process. On

the contrary, my analysis reveals that in every Canadian Anglophone province and

territory, a similar educational discourse on students diversity prevails.

Conclusions

Although addressing the diversity of school populations does not appear to be a priority for

contemporary Canadian education policies, my analysis revealed that it continues to be

a priority for school staff in provinces across Canada. Notwithstanding 3040 years of

experience with growing diversity in Canadian schools, school personnel continue to be

affected by increased diversity. Participants said they nd it challenging to meet the needs

of a diverse student population and that they lack the training they need to work with these

students.

In my analysis I attempted to demonstrate that the notion of multicultural education

remains at the core of school educators discourse, particularly in schools in Canadas

Racial and ethnic diversity in schools 217

1 3

English language sector, independent of the province or territory. I also showed that

teachers and principals do not include minority students when they think about the

norm. Talking about the school situation in Ontario, Connelly (2008) shares her views:

In spite of ofcial policy advocating for equity approaches to education, the struc-

turing of school and society also continues to be informed by a decit-oriented

approach to newcomers knowledge, consistent with a long tradition of remedial

education that privileges norms associated with a white, male, able, northwest-

ern, euro-american standard of superiority, civilization, achievement, and excel-

lence, against which the difference of recent immigrants under recognized

background knowledge is perceived in terms of a potential weakness [] (p. 166)

The results indicate that many school personnel still perceive racial and ethnic minorities

as students who do not always t into school. They still consider them to be others,

especially when a student presents a problem, even when teachers and principals say

that their students are all the same for them. The ofcial discourse, despite a desire to show

inclusiveness, remains vague about how this can be practically accomplished. I agree that

teachers and principals deserve greater support to better meet the needs of these students,

even though the school per se is not yet a place that is free of inequalities. In that vein, I

agree with Popkewitz (1998), who points out that the spatial politics of schooling is the

production of a moral order that includes and excludes (p. 129). Critical educators

denounce the lack of training for teachers at both the pre-service and in-service levels in

the area of critical awareness, which impacts on their potential role as agents of change. As

King (2004) explains,

To consider seriously the value commitment involved in teaching for social change

as an option, students need experiential opportunities to recognize and evaluate the

ideological inuences that shape their thinking about schooling, society, themselves

and diverse others. The critique of ideology, identity and miseducation described

herein represents a form of cultural politics in teacher education that is needed to

address the specic rationality of social inequity in modern American society. (p. 80)

These results correspond to what Giroux (1988) has claimed for years: that schools of

education rarely encourage their students to take seriously the imperatives of social critique

and social change as part of a wider emancipatory vision (p. 183). Transformative

possibilities exist in school, and school personnel should be trained to see which ones could

be achieved in their respective contexts (Solomon and Levine-Rasky 1996, 2003), within

the limits imposed by the existing educational structure (Gerin-Lajoie 2008).

The type of integration that we are witnessing in schools today is still failing the students.

Perhaps it is time to shift the focus and interrogate the type of actions taken in the past to

meet the needs of an increasingly diverse school population. It is time to ensure that students

are empowered. To do so, however, school personnel must be prepared to inquire critically

about what needs to be changed for schools to become truly inclusive of all students.

References

Anderson, S. E., & Fullan, M. (1985). Policy implementation issues for multicultural education at the school

board level. Multiculturalism, 9(1), 1720.

Ball, S. J. (2004). Performativities and fabrications in the education economy. In S. J. Ball (Ed.), The

RoutledgeFalmer reader in sociology of education (pp. 143155). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

218 D. Gerin-Lajoie

1 3

Banks, J. A. (2004). Multicultural education: Historical development, dimensions, and practice. In J.

A. Banks & C. A. McGee Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (pp. 329).

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Connelly, C. (2008). Marking bodies: Globalization, neoliberalism and inhabiting the discursive production

of outstanding Canadian education. In D. Gerin-Lajoie (Ed.), Educators discourses on student

diversity in Canada: Context, policy and practice (pp. 163182). Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Dei, G. J. F. (2011). In defense of ofcial multiculturalism and recognition of the necessity of critical anti-

racism. Canadian Issues/The`mes Canadiens, 35(13), 1519.

Foucault, M. (1972). Archaeology of knowledge. New York: Pantheon.

Gerin-Lajoie, D. (1995). Les ecoles minoritaires de langue francaise canadiennes a` lheure du pluralisme

ethnoculturel [The Canadian French minority language schools in times of ethnocultural pluralism].

E

tudes ethniques au Canada/Canadian Ethnic Studies, 27(1), 3247.

Gerin-Lajoie, D. (2002). Le role du personnel enseignant dans le processus de reproduction linguistique et

culturel en milieu scolaire francophone en Ontario [Teachers role in the process of linguistic and

cultural reproduction in French language schools in Ontario]. Revue des sciences de leducation, 28(1),

125146.

Gerin-Lajoie, D. (Ed.). (2008). Educators discourses on student diversity in Canada: Context, policy and

practice. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Ghosh, R., Zimman, R., & Abdulaziz, T. (1995). Policies relating to the education of cultural communities

in Quebec. E

tudes ethniques au Canada/Canadian Ethnic Studies, 27(1), 1831.

Giroux, H. (1988). Schooling and the struggle for public life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gosh, R. (2011). The liberating potential of multiculturalism in Canada: Ideals and realities. Canadian

Issues/The`mes Canadiens, 23(12), 38.

Harper, H. (1997). Difference and diversity in Ontario schooling. Canadian Journal of Education, 22(2),

192206.

Henry, F., & Tator, C. (1999). State policy and practices as racialized discourse: Multiculturalism, the

charter and employment equity. In P. S. Li (Ed.), Race and ethnic relations in Canada (pp. 88115).

Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Jacquet, M. (2008). The discourse on diversity in British Columbia public schools: From difference to in/

difference. In D. Gerin-Lajoie (Ed.), Educators discourses on student diversity in Canada: Context,

policy and practice (pp. 5179). Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

James-Wilson, S. (2007). Using representation to conceptualize a social justice approach to urban teacher

preparation. In R. P. Salomon & D. N. R. Sekayi (Eds.), Urban teacher education and teaching (pp.

1731). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Jones, B. M. (2000). Multiculturalism and citizenship: The status of visible minorities in Canada.

Canadian Ethnic Studies, 32(1), 111125.

King, J. E. (2004). Dysconscious racism: Ideology, identity, and the miseducation of teachers. In G. Ladson-

Billings & D. Gillborn (Eds.), The RoutledgeFalmer reader on multicultural education (pp. 7183).

London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Knight, M. (2008). Our school is like the United Nations: An examination of how the discourse of

diversity in schooling naturalizes whiteness and white privilege. In D. Gerin-Lajoie (Ed.), Educators

discourses on student diversity in Canada: Context, policy and practice (pp. 81108). Toronto:

Canadian Scholars Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African-American children. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ministry of Justice (1971). Multiculturalism policy of Canada. Ottawa: Library of Parliament.

Mujawamariya, D., & Mahrouse, G. (2004). Multicultural education in Canadian pre-service programmes:

Teacher candidates perspectives. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 50(4), 336353.

Niesz, T. (2006). Beneath the surface: Teacher subjectivities and the appropriation of critical pedagogies.

Equity and Excellence in Education, 39, 335344.

Ontario Ministry of Education and Training (1993). Antiracism and ethnocultural equity in school boards:

Guidelines for policy development and implementation. Toronto: Government of Ontario.

Ouellet, F. (1986). Teachers preparation for intercultural education. In R. J. Samuda & S. L. Kong (Eds.),

Multicultural education: Programs and methods (pp. 1524). Toronto: Intercultural Social Sciences.

Popkewitz, T. S. (1998). Struggling for the soul: The politics of schooling and the construction of the

teacher. New York: Teachers College Press.

Ruitenberg, C. W. (2011). Diversity and education for entanglement. Canadian Issues/The`mes canadiens,

7(5), 2023.

Racial and ethnic diversity in schools 219

1 3

Shaikh, S. (2006). Promoting equitable schools: The role of equity policies in Toronto-area schools

(Unpublished M.A. thesis). Toronto: University of Toronto.

Sleeter, C. E. (2004). How white teachers construct race. In G. Ladson-Billings & D. Gillborn (Eds.), The

RoutledgeFalmer reader in multicultural education (pp. 163178). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Sleeter, C. E., & Delgado-Bernal, D. (2004). Critical pedagogy, critical race theory, and antiracist education.

In J. A. Banks & C. A. McGee Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (pp.

240258). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sleeter, C. E., & Grant, C. A. (1991). Mapping terrains of power: Student cultural knowledge versus

classroom knowledge. In C. E. Sleeter (Ed.), Empowerment through multicultural education (pp.

4968). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Solomon, R. P., & Levine-Rasky, C. (1996). Transforming teacher education for an antiracism pedagogy.

Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 33(3), 337359.

Solomon, R. P., & Levine-Rasky, C. (2003). Teaching for equity and diversity: Research to practice.

Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Tator, C., & Henry, F. (1991). Multicultural education: Translating policy into practice. Ottawa: Depart-

ment of Multiculturalism and Citizenship.

van Dijk, T. A. (1993). Elite discourse and racism. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Author Biography

Diane Gerin-Lajoie (Canada) is a critical sociologist of education and professor in the department of

Curriculum, Teaching and Learning at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), at the

University of Toronto. She is also a researcher at the Centre de recherches en education franco-ontarienne

(CREFO) at the same institute, and a member of the Observatoire Jeunes et Societe in Quebec. She conducts

research on linguistic minorities in the areas of identity construction among youth and on teachers work in

minority settings and professional identity. Having studied Francophones in Ontario, she is now studying

Anglophones in Quebec. She teaches graduate courses in the areas of minority education and qualitative

research.

220 D. Gerin-Lajoie

1 3

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Systematic Instruction PlanDokument3 SeitenSystematic Instruction Planapi-400639263Noch keine Bewertungen

- Multicultural Education in The New CenturyDokument7 SeitenMulticultural Education in The New CenturyJeshwary KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- G8 DLL Health-2Dokument6 SeitenG8 DLL Health-2Crys Alvin Matic100% (3)

- 1509 - Smriti Argumentative EssayDokument10 Seiten1509 - Smriti Argumentative EssayShreya SarkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dealing With Difference: Building Culturally Responsive ClassroomsDokument16 SeitenDealing With Difference: Building Culturally Responsive ClassroomsKim ThuyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edu 302: Assignment 4Dokument5 SeitenEdu 302: Assignment 4Faith AmosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Beauty of A Rainbow Takes Shape in Its Separate ColorsDokument7 SeitenThe Beauty of A Rainbow Takes Shape in Its Separate Colorswsgf khiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational Research: To Cite This Article: Patricia Bromley (2011) Multiculturalism and Human Rights in CivicDokument15 SeitenEducational Research: To Cite This Article: Patricia Bromley (2011) Multiculturalism and Human Rights in CivicColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Multicultural Literacy PDFDokument27 SeitenWhy Multicultural Literacy PDFRea Rose SaliseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multiculturalism in Canada Term PapersDokument5 SeitenMulticulturalism in Canada Term Papersafmzvadopepwrb100% (2)

- Integrating Language SkillsDokument25 SeitenIntegrating Language Skillsapi-501283068Noch keine Bewertungen

- Multicultural EducationDokument8 SeitenMulticultural Educationjoy penetranteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bedjaoui Cardiff Article For PublicationDokument8 SeitenBedjaoui Cardiff Article For PublicationLina LilyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study of Language Use, Language Attitudes, and Identities in Two French Speaking Communities in The United KingdomDokument12 SeitenStudy of Language Use, Language Attitudes, and Identities in Two French Speaking Communities in The United KingdomWiktoria KarwaszewskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper On Multiculturalism in CanadaDokument7 SeitenResearch Paper On Multiculturalism in Canadaqzafzzhkf100% (1)

- Test 2Dokument24 SeitenTest 2jaysonfredmarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Canadian Curriculum On Indigenous Peoples - Isobel Dunne Ba24Dokument8 SeitenThe Impact of Canadian Curriculum On Indigenous Peoples - Isobel Dunne Ba24api-717093895Noch keine Bewertungen

- Citizenship, Becoming, Literacy and Schools: Immigrant Students in A Canadian Secondary SchoolDokument10 SeitenCitizenship, Becoming, Literacy and Schools: Immigrant Students in A Canadian Secondary Schoolapi-277625437Noch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction Curriculum Multiculturalism Boarding SchoolDokument6 SeitenIntroduction Curriculum Multiculturalism Boarding SchoolDiceMidyantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Project Express Hill PDFDokument20 SeitenFinal Project Express Hill PDFPatricia Rodriguez ToledoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessing Ethiopian Primary School Second Cycle Social Studies Textbooks For Adequate Reflections of MulticulturalismDokument10 SeitenAssessing Ethiopian Primary School Second Cycle Social Studies Textbooks For Adequate Reflections of MulticulturalismTadesse HabteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urban Language & Literacies: Working Papers inDokument20 SeitenUrban Language & Literacies: Working Papers inMubina11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ethnic Studies or Multicultural EducationDokument7 SeitenEthnic Studies or Multicultural EducationRalucaFilipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multicultural Education and Intercultural Education: Is There A Difference?Dokument20 SeitenMulticultural Education and Intercultural Education: Is There A Difference?hadi yantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Xaxa 21Dokument7 SeitenXaxa 21Armaan AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communicating Across Cultures: Module OutlineDokument24 SeitenCommunicating Across Cultures: Module OutlineAyu WulandariNoch keine Bewertungen

- BANKS - Citizenship and DiversityDokument12 SeitenBANKS - Citizenship and DiversityRemy LøwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inmigración en Canadá PDFDokument19 SeitenInmigración en Canadá PDFyisselNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dissertation MulticulturalismDokument5 SeitenDissertation MulticulturalismDltkCustomWritingPaperUK100% (1)

- Articl1 PDFDokument11 SeitenArticl1 PDFsafiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Improving Cultural Competence by Teaching Multicultural EducationDokument19 SeitenImproving Cultural Competence by Teaching Multicultural EducationMave ExNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Does It Mean To Be Bilingual in A Monolingual SocietyDokument8 SeitenWhat Does It Mean To Be Bilingual in A Monolingual SocietyEdna VegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Danica Taylor BordersDokument15 SeitenDanica Taylor BordersColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection On The Impacts of Shifting Cultural MdenizDokument4 SeitenReflection On The Impacts of Shifting Cultural Mdenizapi-273275279Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kubota, Ryuko. Critical Multiculturalism and Second Language EducationDokument23 SeitenKubota, Ryuko. Critical Multiculturalism and Second Language EducationanacfeNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critical Multicultural Analysis of A Romanian Textbook Taught in Elementary International Language ProgramsDokument16 SeitenA Critical Multicultural Analysis of A Romanian Textbook Taught in Elementary International Language ProgramsDorian StoilescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advancement of Equity (5pg)Dokument8 SeitenAdvancement of Equity (5pg)Kevin KibugiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACDE 2010, Accord On Indigenous EducationDokument8 SeitenACDE 2010, Accord On Indigenous EducationMelonie A. FullickNoch keine Bewertungen

- MulticulturismDokument8 SeitenMulticulturismRose DonquilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- California Ethnic Studies Model CurriculumDokument696 SeitenCalifornia Ethnic Studies Model CurriculumDon DoehlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canada Multiculturalism KYMLICKADokument33 SeitenCanada Multiculturalism KYMLICKANil SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global and Multicultural LiteracyDokument3 SeitenGlobal and Multicultural Literacyrollence100% (1)

- IIIInternationalColloquiumProceedings Split MergeDokument13 SeitenIIIInternationalColloquiumProceedings Split MergeQinyuan ZhangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Cultural Diversity and Diverse Identities: January 2020Dokument11 SeitenUnderstanding Cultural Diversity and Diverse Identities: January 2020Swagata DeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multicultural Education: A Challenge To The Global TeachersDokument16 SeitenMulticultural Education: A Challenge To The Global TeachersPATRICIA JANE CAQUILALANoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational Equity in Canada The Case of Ontario S Strategies and Actions To Advance Excellence and Equity For StudentsDokument21 SeitenEducational Equity in Canada The Case of Ontario S Strategies and Actions To Advance Excellence and Equity For Studentscie92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper MulticulturalismDokument6 SeitenResearch Paper Multiculturalismasdlukrhf100% (1)

- Beliefs of Two Culturally Diverse Groups of Teachers About Intercultural Bilingual EducationDokument15 SeitenBeliefs of Two Culturally Diverse Groups of Teachers About Intercultural Bilingual Educationpaula ruizNoch keine Bewertungen

- MulticulturalismDokument60 SeitenMulticulturalismFerdie Mhar Prado Ricasio50% (2)

- Surigao Del Sur State University: WWW - Sdssu.edu - PHDokument8 SeitenSurigao Del Sur State University: WWW - Sdssu.edu - PHJocelyn Rivas BellezasNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dimensions of Multicultural EducationDokument6 SeitenThe Dimensions of Multicultural EducationERWIN MORGIANoch keine Bewertungen

- ETFO - Aboriginal History and Realities in Canada - Grades 1-8 Teachers' ResourceDokument4 SeitenETFO - Aboriginal History and Realities in Canada - Grades 1-8 Teachers' ResourceRBeaudryCCLENoch keine Bewertungen

- Didactic S of Languages and CulturesDokument10 SeitenDidactic S of Languages and Culturesjairo alberto galindo cuestaNoch keine Bewertungen

- KoikeLacorte2014 CultureDokument17 SeitenKoikeLacorte2014 Culturejorge_chilla7689Noch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Cultural Diversityand Diverse IdentitiesDokument11 SeitenUnderstanding Cultural Diversityand Diverse IdentitiesgabbymacaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aculturacion País VascoDokument15 SeitenAculturacion País VascoFlorin NicolauNoch keine Bewertungen

- Linguisticcolonialisminthe English Language TextbooksDokument19 SeitenLinguisticcolonialisminthe English Language TextbooksTrần Hoàng KhanhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multiculturalism Thesis TopicsDokument7 SeitenMulticulturalism Thesis Topicsf1t1febysil2100% (2)

- Thirteenth Amendment: NotesDokument7 SeitenThirteenth Amendment: NotesGlory Vie OrallerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 18 The Cultural Plunge ImmersionDokument10 Seiten18 The Cultural Plunge ImmersionAbdaouiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gift of Languages: Paradigm Shift in U.S. Foreign Language EducationVon EverandThe Gift of Languages: Paradigm Shift in U.S. Foreign Language EducationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scramble For AfricaDokument20 SeitenScramble For AfricaColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whole UnitDokument23 SeitenWhole UnitColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1914 1918 Online Imperialism 2015 03 04Dokument17 Seiten1914 1918 Online Imperialism 2015 03 04Colton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAINCauses Sources 2014Dokument8 SeitenMAINCauses Sources 2014Colton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 28 The Crisis of The Imperial Order 1900-1929Dokument36 SeitenChapter 28 The Crisis of The Imperial Order 1900-1929Colton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Press Offense: Vs Half-Cout TrapDokument1 SeitePress Offense: Vs Half-Cout TrapColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trench Source CollectionDokument33 SeitenTrench Source CollectionColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 30x30 AssignmentDokument2 Seiten30x30 AssignmentColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seating ChartDokument1 SeiteSeating ChartColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beating The Half-Court and Three-Quarter-Court Press - Trap - Extreme Basketball SDokument4 SeitenBeating The Half-Court and Three-Quarter-Court Press - Trap - Extreme Basketball SColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steve Nash 20 Minute Workout-1Dokument5 SeitenSteve Nash 20 Minute Workout-1eretriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Junior Boys - City Championship - 2017Dokument2 SeitenJunior Boys - City Championship - 2017Colton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagrams 3 Full Courts Us ADokument1 SeiteDiagrams 3 Full Courts Us AColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Career Life Education Elaborations PDFDokument2 SeitenCareer Life Education Elaborations PDFColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- About Orange Shirt DayDokument1 SeiteAbout Orange Shirt DayColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canada's Labour Movement Has A Long History of Improving Workers' Everyday LivesDokument10 SeitenCanada's Labour Movement Has A Long History of Improving Workers' Everyday LivesColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21-5 Parliament Limits English MonarchyDokument13 Seiten21-5 Parliament Limits English MonarchyColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- In What Follows This Paper Will Discuss How BICS-Contextualized or Conversational Language FluencyDokument4 SeitenIn What Follows This Paper Will Discuss How BICS-Contextualized or Conversational Language FluencyColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Was The Depression and What Caused It?: Directions: Read The Following Handout and Answer The Questions ProvidedDokument2 SeitenWhat Was The Depression and What Caused It?: Directions: Read The Following Handout and Answer The Questions ProvidedColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Imperialism: Directions: Read The Following Handout and Answer The Questions ProvidedDokument2 SeitenImperialism: Directions: Read The Following Handout and Answer The Questions ProvidedColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seating ChartDokument1 SeiteSeating ChartColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- DSM5 Reflection 1 Low Incidence Exceptionalities Autism Spectrum DisorderDokument4 SeitenDSM5 Reflection 1 Low Incidence Exceptionalities Autism Spectrum DisorderColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Big Era Eight A Half Century of Crisis 1900 - 1950 CEDokument37 SeitenBig Era Eight A Half Century of Crisis 1900 - 1950 CEGayatrie PathakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethnic and Racial StudiesDokument13 SeitenEthnic and Racial StudiesColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1176989Dokument8 Seiten1176989Colton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ww2 1Dokument14 Seitenww2 1Colton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal #1: (Due: December 2) Does Money Buy Happiness? 200+ Words Informal Double SpacedDokument1 SeiteJournal #1: (Due: December 2) Does Money Buy Happiness? 200+ Words Informal Double SpacedColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Christmas Carol ProjectDokument1 SeiteA Christmas Carol ProjectColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2940894Dokument4 Seiten2940894Colton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Educational Research AssociationDokument48 SeitenAmerican Educational Research AssociationColton McKeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Career MobilityDokument11 SeitenCareer MobilityAmir RiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- EAPP MediaDokument2 SeitenEAPP MediaJaemsNoch keine Bewertungen

- FS3 Principles in Teaching P.1Dokument11 SeitenFS3 Principles in Teaching P.1mejaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- RSML - 5 - e - 8 Etsot - Eleot AlignmentDokument2 SeitenRSML - 5 - e - 8 Etsot - Eleot AlignmentkhalafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume Profesional Biru Tua Dan HitamDokument2 SeitenResume Profesional Biru Tua Dan HitamCallista NathaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PW FINCO - Remedial Instruction Programme - Panel Heads Training Day 2 Formatted - FINALDokument31 SeitenPW FINCO - Remedial Instruction Programme - Panel Heads Training Day 2 Formatted - FINALlizNoch keine Bewertungen

- CFAK-Girl Power Project ProposalDokument21 SeitenCFAK-Girl Power Project ProposalAyuba Daniel La'ah100% (1)

- Literacy Action-PlanDokument5 SeitenLiteracy Action-PlanJanette Portillas LumbayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trainers MethodologyDokument3 SeitenTrainers MethodologyPamela LogronioNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Sample A Recommendation Letter: February 2019Dokument3 SeitenA Sample A Recommendation Letter: February 2019AbdullahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using Total Physical Response (TPR) Method On Young Learners English Language TeachingDokument9 SeitenUsing Total Physical Response (TPR) Method On Young Learners English Language Teachingmasri'ah sukirnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Human Resource Management INE3023: International Training, Training, Development & CareersDokument32 SeitenInternational Human Resource Management INE3023: International Training, Training, Development & CareersHuyền Oanh ĐinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rubric Project Design June2010Dokument4 SeitenRubric Project Design June2010TikvahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design Thinking BrochureDokument2 SeitenDesign Thinking Brochuremahesh24pkNoch keine Bewertungen

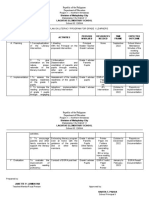

- Wali Is Mps 1819 1stto4thDokument7 SeitenWali Is Mps 1819 1stto4thJacqueline Tolentino CabridoNoch keine Bewertungen

- (AC-S02) Week 2 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Test Your Previous Knowledge - INGLES II (16481)Dokument5 Seiten(AC-S02) Week 2 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Test Your Previous Knowledge - INGLES II (16481)Carlos Martin AmpudiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Assessment Gathering ToolDokument10 SeitenReading Assessment Gathering ToolJulius BayagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing Knowledge Management and The Nurse Leaders' RoleDokument14 SeitenA Systematic Review of Factors Influencing Knowledge Management and The Nurse Leaders' RoleoohscNoch keine Bewertungen

- Informal and Formal Social Studies CurriculumDokument7 SeitenInformal and Formal Social Studies CurriculumJesujoba OsuolaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLL Fbs Week 1 2018 19Dokument7 SeitenDLL Fbs Week 1 2018 19Joie MyrrhNoch keine Bewertungen

- PE 8 DLL Q1 1st WeekDokument3 SeitenPE 8 DLL Q1 1st WeekMarvin AbadNoch keine Bewertungen