Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Lost Command

Hochgeladen von

Dianne Esidera Rosales100%(2)100% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (2 Abstimmungen)

565 Ansichten8 Seitenlost command paper in northern samar

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenlost command paper in northern samar

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

100%(2)100% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (2 Abstimmungen)

565 Ansichten8 SeitenLost Command

Hochgeladen von

Dianne Esidera Rosaleslost command paper in northern samar

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 8

Kumander Bucay: Living the ghost of his past

By: Edwin Espejo

GENERAL SANTOS CITY Circa 1975. Norberto Manero was leading a force of more than 250

fully armed civilians trekking the mountains of Davao del Sur and the then undivided South

Cotabato.

For five long months, they scoured the perilous jungles and crossed the treacherous rivers in

search for Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) rebels who had opened up several war fronts

as Mindanao came almost on the brink of civil war.

Inside his backpack were reams of amnesty papers signed by no less Juan Ponce Enrile, then

defense secretary under the martial law regime of President Ferdinand Marcos.

Manero, a.k.a. Kumander Bucay, was barely out of his 20s. By then, he was already cultivating

an image that would become one of the most feared if not hated figures in the history of the

Mindanao conflict.

From the accounts of his armed forays in the mountains of Mindanao hunting down the MNLF

and NPA rebels, Manero could have become a good military commander had he joined the

Armed Forces.

Norberto Manero was then emerging from the shadows of the late Feliciano Luces alyas

Kumander Toothpick, the man who he said was the founder of the dreaded and infamous Ilaga

group.

Yet, two years earlier, Manero literally faced the firing squad of the Marcos regime for multiple

murder, massacre and arson.

He was being un-cuffed and was already facing a squad from the defunct Philippine

Constabulary when a radio message from then Central Mindanao Command chief Maj. Gen.

Fortunato Abat arrived, which spared him from execution.

It was his closest brush with death.

For that, Manero would be forever grateful to the late lawyer Cornelio Falgui, former mayor of

Kiamba town which is now part of Sarangani province.

It was Falgui who pulled some strings to let Manero off the hook. That harrowing experience

would soon be transformed into storied brutality which culminated in the murder of Italian

missionary Fr. Tulio Favali in Tulunan, North Cotabato a decade after.

To protect himself from the clutches of a Davao del Sur mayor who filed the murder charges

against him, Manero joined the group of Lost Command chief Lt. Col. Laudemer Lademora and

a certain Sgt. Valdez. Lademoras group sowed fear and terror throughout Mindanao and even

as far as Samar. Manero said he was once sent to Samar to go after the NPA rebels.

When Manero was exonerated, the mayor of Magsaysay town who filed the murder and

massacre raps against Kumander Bucay, sold all his properties and migrated to the US. So too

was the officer of the would-be PC firing squad, Filipino Amoguis, who likewise settled in the US

upon retiring as a general in the Philippine National Police.

Documentation for The Lost Command

Feb. 26, 1982

The New York Times

Around Davao, there is much talk of the ''lost command'' a mysterious paramilitary unit that

has been accused of extreme brutality

March 15, 1982

Newsweek

He presides over an outfit nicknamed the Lost Command: a clandestine army of275 to 400

irregulars whose ostensible mission is to search out and destroy the enemies of President

Ferdinand Marcos on the Philippine island of Mindanao. The colonel is very good at the job.

"I'm not a mad killer," he says mOver the past 31 years xxhas killed countless communist Huks,

nonpartisan bandits and Muslim insurgents. Technically he is a coloneI in the Armed Forces of

the Philippines....

His group earned its nickname after surviving a hopeless last stand against a band of Muslim

rebels in 1973. Since then xxxhas filled out his ranks with deserters and other desperadoes

willing to "go where others would not go and do what others would not do."

..Last September six men from the Lost Command got into a scrape and gunned down three

policemen and a government militiaman in Luzon. Confronted with the facts, Lademora

dispatched a hit team to track down the killers. Within 24 hours all six were dead.

March 15, 1982

Newsweek

The Lost Command, they point out, spends a good deal of its energy protecting large logging

and plantation interests in areas where the poor are desperate for land. In towns through five

eastern Mindanao provinces, gunmen identifying themselves with the Lost Command have

been extorting from small traders and businessmen. Some of the charges are worse: that xx's

men may have terror-bombed a church Easter service, and that they massacred men, women

and children in one village while looking for communists on the island of Samar last fall. The

accusations infuriate xx; he blames the bombing and the massacre on Muslim and communist

insurgents and attributes the rest to communist propaganda or to "bad elements" ...

Ravaging Samar island during martial law years

Historical data showed that continuous and rapid and systematic destruction of Samar island's

rain forests occurred in the last four decades. The primary cause of this deforestation was

commercial logging. During the whole decade of the seventies, when the whole country was

under martial law, the entire forests of Samar island were licensed to commercial logging

companies for exploitation.

Timber Licensing Agreements or TLAs were the main instrument used to exploit the forests. In

the "Politics of Plunder", author Marites Vitug says that "forest concessions used to be handed

out by the different administrations at a frenzied rate. President Ferdinand Marcos, used the

TLA to reward supporters, enrich friends and family and keep politicians under his patronage."

Under Marcos, the number of timber licenses in the country leaped from 58 in 1969 to 230 in

1977, the highest recorded figure.

Samar island was a "pie" President Marcos carved into logging concessions for his cronies and

friends. The largest of these concessions (95,770 hectares) was granted to then Defense

Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile who owned the San Jose Timber. His license to cut timber extends

up to the year 2007. Second largest concession was granted to Great Pacific Industries, Inc.

owned by family of once Philippine Ambassador to Japan, the Yuchengco Family. Its license,

however, was suspended in 1985 due to violations of its terms and conditions.

Senator Enrile's logging operations in Samar was reportedly protected by the

"Lost Command" headed by Renegade PC Col. Carlos Lademora, also known as Commander

Brown. His group figured in the massacre of 45 men, women and children in Brgy. Sag-od, Las

Navas town of Northern Samar in September 1981. They were "commissioned to enforce order

in Sag-od where the operations of a logging company were reportedly being disrupted by the

strong presence of the New People's Army. The timber firm's logging concession used to border

Sag-od.." (Petilla, Phil. Daily Inquirer, Sept. 15, 1989).

Replicating the pattern in the country, the number of timber licensees in Samar island leaped

from one TLA in 1967 to 15 by 1978. The concessionaries who were not from Samar. Even the

precious Mancono forests (Philippine ironwood) in Homonhon Island were not spared. The

total logging concessions added up to 599,000 hectares, equivalent to 47% of the total land

area of Samar. The total allowable cut per year was 373,277 hectares cubic meters (Cramer).

But we all knew that the loggers cut more that they were allowed. In fact, in 1986, six of TLAs

were suspended due to non-compliance with its terms and conditions. One concession,

Western Palawan, was cancelled in 1989 due to its overcutting. (Bautista, The Logging

Moratorium Policy in Nueva Ecija, Nueva Viscaya and Samar). Deforestation legally and steadily

increased over the years and Samar and its people did benefit from the plunder of its forest

resources.

Kumander Bucay: Living the ghost of his past

By: Edwin Espejo

GENERAL SANTOS CITY Circa 1975. Norberto Manero was leading a force of more than 250

fully armed civilians trekking the mountains of Davao del Sur and the then undivided South

Cotabato.

For five long months, they scoured the perilous jungles and crossed the treacherous rivers in

search for Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) rebels who had opened up several war fronts

as Mindanao came almost on the brink of civil war.

Inside his backpack were reams of amnesty papers signed by no less Juan Ponce Enrile, then

defense secretary under the martial law regime of President Ferdinand Marcos.

Manero, a.k.a. Kumander Bucay, was barely out of his 20s. By then, he was already cultivating

an image that would become one of the most feared if not hated figures in the history of the

Mindanao conflict.

From the accounts of his armed forays in the mountains of Mindanao hunting down the MNLF

and NPA rebels, Manero could have become a good military commander had he joined the

Armed Forces.

Norberto Manero was then emerging from the shadows of the late Feliciano Luces alyas

Kumander Toothpick, the man who he said was the founder of the dreaded and infamous Ilaga

group.

Yet, two years earlier, Manero literally faced the firing squad of the Marcos regime for multiple

murder, massacre and arson.

He was being un-cuffed and was already facing a squad from the defunct Philippine

Constabulary when a radio message from then Central Mindanao Command chief Maj. Gen.

Fortunato Abat arrived, which spared him from execution.

It was his closest brush with death.

For that, Manero would be forever grateful to the late lawyer Cornelio Falgui, former mayor of

Kiamba town which is now part of Sarangani province.

It was Falgui who pulled some strings to let Manero off the hook. That harrowing experience

would soon be transformed into storied brutality which culminated in the murder of Italian

missionary Fr. Tulio Favali in Tulunan, North Cotabato a decade after.

To protect himself from the clutches of a Davao del Sur mayor who filed the murder charges

against him, Manero joined the group of Lost Command chief Lt. Col. Laudemer Lademora and

a certain Sgt. Valdez. Lademoras group sowed fear and terror throughout Mindanao and even

as far as Samar. Manero said he was once sent to Samar to go after the NPA rebels.

When Manero was exonerated, the mayor of Magsaysay town who filed the murder and

massacre raps against Kumander Bucay, sold all his properties and migrated to the US. So too

was the officer of the would-be PC firing squad, Filipino Amoguis, who likewise settled in the US

upon retiring as a general in the Philippine National Police.

Documentation for The Lost Command

Feb. 26, 1982

The New York Times

Around Davao, there is much talk of the ''lost command'' a mysterious paramilitary unit that

has been accused of extreme brutality

March 15, 1982

Newsweek

He presides over an outfit nicknamed the Lost Command: a clandestine army of275 to 400

irregulars whose ostensible mission is to search out and destroy the enemies of President

Ferdinand Marcos on the Philippine island of Mindanao. The colonel is very good at the job.

"I'm not a mad killer," he says mOver the past 31 years xxhas killed countless communist Huks,

nonpartisan bandits and Muslim insurgents. Technically he is a coloneI in the Armed Forces of

the Philippines....

His group earned its nickname after surviving a hopeless last stand against a band of Muslim

rebels in 1973. Since then xxxhas filled out his ranks with deserters and other desperadoes

willing to "go where others would not go and do what others would not do."

..Last September six men from the Lost Command got into a scrape and gunned down three

policemen and a government militiaman in Luzon. Confronted with the facts, Lademora

dispatched a hit team to track down the killers. Within 24 hours all six were dead.

March 15, 1982

Newsweek

The Lost Command, they point out, spends a good deal of its energy protecting large logging

and plantation interests in areas where the poor are desperate for land. In towns through five

eastern Mindanao provinces, gunmen identifying themselves with the Lost Command have

been extorting from small traders and businessmen. Some of the charges are worse: that xx's

men may have terror-bombed a church Easter service, and that they massacred men, women

and children in one village while looking for communists on the island of Samar last fall. The

accusations infuriate xx; he blames the bombing and the massacre on Muslim and communist

insurgents and attributes the rest to communist propaganda or to "bad elements" ...

Ravaging Samar island during martial law years

Historical data showed that continuous and rapid and systematic destruction of Samar island's

rain forests occurred in the last four decades. The primary cause of this deforestation was

commercial logging. During the whole decade of the seventies, when the whole country was

under martial law, the entire forests of Samar island were licensed to commercial logging

companies for exploitation.

Timber Licensing Agreements or TLAs were the main instrument used to exploit the forests. In

the "Politics of Plunder", author Marites Vitug says that "forest concessions used to be handed

out by the different administrations at a frenzied rate. President Ferdinand Marcos, used the

TLA to reward supporters, enrich friends and family and keep politicians under his patronage."

Under Marcos, the number of timber licenses in the country leaped from 58 in 1969 to 230 in

1977, the highest recorded figure.

Samar island was a "pie" President Marcos carved into logging concessions for his cronies and

friends. The largest of these concessions (95,770 hectares) was granted to then Defense

Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile who owned the San Jose Timber. His license to cut timber extends

up to the year 2007. Second largest concession was granted to Great Pacific Industries, Inc.

owned by family of once Philippine Ambassador to Japan, the Yuchengco Family. Its license,

however, was suspended in 1985 due to violations of its terms and conditions.

Senator Enrile's logging operations in Samar was reportedly protected by the

"Lost Command" headed by Renegade PC Col. Carlos Lademora, also known as Commander

Brown. His group figured in the massacre of 45 men, women and children in Brgy. Sag-od, Las

Navas town of Northern Samar in September 1981. They were "commissioned to enforce order

in Sag-od where the operations of a logging company were reportedly being disrupted by the

strong presence of the New People's Army. The timber firm's logging concession used to border

Sag-od.." (Petilla, Phil. Daily Inquirer, Sept. 15, 1989).

Replicating the pattern in the country, the number of timber licensees in Samar island leaped

from one TLA in 1967 to 15 by 1978. The concessionaries who were not from Samar. Even the

precious Mancono forests (Philippine ironwood) in Homonhon Island were not spared. The

total logging concessions added up to 599,000 hectares, equivalent to 47% of the total land

area of Samar. The total allowable cut per year was 373,277 hectares cubic meters (Cramer).

But we all knew that the loggers cut more that they were allowed. In fact, in 1986, six of TLAs

were suspended due to non-compliance with its terms and conditions. One concession,

Western Palawan, was cancelled in 1989 due to its overcutting. (Bautista, The Logging

Moratorium Policy in Nueva Ecija, Nueva Viscaya and Samar). Deforestation legally and steadily

increased over the years and Samar and its people did benefit from the plunder of its forest

resources.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- SagodDokument3 SeitenSagodAlex Olesco100% (1)

- Agents of Apocalypse: Epidemic Disease in the Colonial PhilippinesVon EverandAgents of Apocalypse: Epidemic Disease in the Colonial PhilippinesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Excerpts From Edsa UnoDokument14 SeitenExcerpts From Edsa UnoNica Andrae Esperante100% (2)

- Upsurge of People's Resistance in the Philippines and the WorldVon EverandUpsurge of People's Resistance in the Philippines and the WorldBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Glenn MayDokument22 SeitenGlenn MayZonia Mae CuidnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literature of The Philippines PDFDokument6 SeitenThe Literature of The Philippines PDFDherick Raleigh0% (1)

- CW Readings GLOBAL MEDIADokument15 SeitenCW Readings GLOBAL MEDIAhotgirlsummer100% (1)

- José Rizal: Philippine National Hero Who Inspired RevolutionDokument4 SeitenJosé Rizal: Philippine National Hero Who Inspired RevolutionCHRISTENE FEB LACHICANoch keine Bewertungen

- American Presence and Their Colonial RuleDokument48 SeitenAmerican Presence and Their Colonial RulejanereymarkzetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ten Turning Points of Philippine HistoryDokument2 SeitenTen Turning Points of Philippine Historyjjj100% (1)

- Marcos - Human Rights ViolationsDokument16 SeitenMarcos - Human Rights ViolationscrystalwatersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rise of Chinese Mestizos in the PhilippinesDokument4 SeitenRise of Chinese Mestizos in the PhilippinesGuilliane GallanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ang Huling Elbimbo - Module 2Dokument1 SeiteAng Huling Elbimbo - Module 2Jomar Fernandez EncontroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ano Nga Ba Ang Martial LawDokument4 SeitenAno Nga Ba Ang Martial LawKrisha AlaizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quezon S CommonwealthDokument25 SeitenQuezon S CommonwealthAlexis Julia CanariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rizal's El Filibusterismo and the Historical Environment During Its WritingDokument4 SeitenRizal's El Filibusterismo and the Historical Environment During Its WritingJonalyn G. De RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jose Rizal Biographical SketchDokument22 SeitenJose Rizal Biographical SketchJhong_Andrade_45910% (1)

- ValuesDokument3 SeitenValuesHermann Dejero LozanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 9 Rizal in Peninsular SpainDokument3 SeitenChapter 9 Rizal in Peninsular SpainGimosPerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reaction Paper On VictimologyDokument6 SeitenReaction Paper On VictimologyCharmis TubilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ocampo - Rizal Dis Not Write Sa Aking Mga KabataDokument5 SeitenOcampo - Rizal Dis Not Write Sa Aking Mga KabataFrankyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barangay MacasandigDokument2 SeitenBarangay MacasandigNorlaine UtaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1 - The Contemporary WorldDokument5 SeitenModule 1 - The Contemporary WorldShanen Marie ArmenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forms of Deviant Behavior and SocialDokument43 SeitenForms of Deviant Behavior and SocialAnaliza J. Ison50% (6)

- Code of Kalantiaw: Forged legal codeDokument3 SeitenCode of Kalantiaw: Forged legal codeRonald GuevarraNoch keine Bewertungen

- SOGIE Inquiries Impact on Student Well-BeingDokument17 SeitenSOGIE Inquiries Impact on Student Well-BeingNicole Andrei RiveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zamboanga City CrisisDokument24 SeitenZamboanga City CrisisjoreyneeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Political Culture and GovernanceDokument38 SeitenPhilippine Political Culture and GovernanceTony AbottNoch keine Bewertungen

- Were There Instances or Attempts of Moro, Lumad and Christian Filipino Cooperation in Their Struggle Against Foreign Colonialism?Dokument2 SeitenWere There Instances or Attempts of Moro, Lumad and Christian Filipino Cooperation in Their Struggle Against Foreign Colonialism?Clinth Jhon100% (1)

- )Dokument18 Seiten)Chilla Mae LimbingNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Propaganda MovementDokument61 SeitenThe Propaganda MovementKENTARNEL ROSAROSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mabini Colleges, Inc. High School Department Daet, Camarines NorteDokument39 SeitenMabini Colleges, Inc. High School Department Daet, Camarines NorteNancy QuiozonNoch keine Bewertungen

- As202 Paper - GuillermoDokument5 SeitenAs202 Paper - GuillermoAnton Gabriel Largoza-Maza100% (1)

- Jose Rizal'S 1St Travel Abroad (1882) A. Travel To SpainDokument8 SeitenJose Rizal'S 1St Travel Abroad (1882) A. Travel To SpainJosh Jarold CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter IDokument8 SeitenChapter IWigan Conda Faicol0% (1)

- b12926863 Simbulan Dante C PDFDokument482 Seitenb12926863 Simbulan Dante C PDFAngela Beatrice100% (1)

- Literature During The Middle Period VFinalDokument19 SeitenLiterature During The Middle Period VFinalMicahjhen Pateña BlanzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Education-For StudentsDokument10 SeitenDrug Education-For StudentskayrinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 8 The Noli Base On TruthDokument7 SeitenChapter 8 The Noli Base On TruthLianna RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Communication Media Transforming Philippines SocietyDokument20 SeitenNew Communication Media Transforming Philippines SocietyJaco JovesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Old Struggle For Human RightsDokument7 SeitenThe Old Struggle For Human RightsReyleyy1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Manila hostage crisis of 2010Dokument16 SeitenManila hostage crisis of 2010Ella HermonioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scenario 2Dokument3 SeitenScenario 2JS DSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Noli AnalysisDokument4 SeitenNoli AnalysisJohann Raphael T. King0% (1)

- Factors Behind Police Performance in the PhilippinesDokument33 SeitenFactors Behind Police Performance in the PhilippinesPJr MilleteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Noli Me Tangere Chapter 63Dokument3 SeitenNoli Me Tangere Chapter 63Benedict LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manila GrandandDokument4 SeitenManila GrandandLarrymagananNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Fifth Theory of Development CommunicationDokument15 SeitenThe Fifth Theory of Development CommunicationJoshua RodilNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Brief History of Crime MappingDokument3 SeitenA Brief History of Crime MappingJohnpatrick DejesusNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Birth of NationDokument43 SeitenThe Birth of Nationjoefrey BalumaNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Terrorism NotesDokument3 SeitenInternational Terrorism NotesFlevian MutieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nicomedes "Nick" Márquez Joaquín: Early Life & FamilyDokument3 SeitenNicomedes "Nick" Márquez Joaquín: Early Life & FamilyJoan DianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Better to Die in War than be InvadedDokument1 SeiteBetter to Die in War than be InvadedChrisjohn Ruadiel JoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3 Gender and Sexuality As A Subject of InquiryDokument4 SeitenLesson 3 Gender and Sexuality As A Subject of InquiryPrincessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life Ni RizalDokument26 SeitenLife Ni RizalAlmineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Philippine Political MemesDokument76 SeitenRunning Head: Philippine Political MemesAna Mae LinguajeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effectiveness of Prison Programs On InmatesDokument18 SeitenThe Effectiveness of Prison Programs On InmateskyletoffoloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 1 Fundamentals of CriminologyDokument16 SeitenLesson 1 Fundamentals of Criminologyhelena arah providoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amado HernandezDokument8 SeitenAmado HernandezEmily Torres DaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- REMEDIAL LAW BAR EXAMINATION QUESTIONSDokument11 SeitenREMEDIAL LAW BAR EXAMINATION QUESTIONSAubrey Caballero100% (1)

- Essential Taxation Law Q&As from Philippine Bar Exams (2007-2013Dokument142 SeitenEssential Taxation Law Q&As from Philippine Bar Exams (2007-2013Dianne MedianeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Examination 2009 Q&ADokument23 SeitenBar Examination 2009 Q&ADianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essential Taxation Law Q&As from Philippine Bar Exams (2007-2013Dokument142 SeitenEssential Taxation Law Q&As from Philippine Bar Exams (2007-2013Dianne MedianeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Examination 2010 Q&ADokument10 SeitenBar Examination 2010 Q&ADianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Exam 2006 Remedial Law QuestionsDokument9 SeitenBar Exam 2006 Remedial Law QuestionsbubblingbrookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Examination 2005 Q&ADokument20 SeitenBar Examination 2005 Q&ADianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Examination 2006 Q&ADokument10 SeitenBar Examination 2006 Q&ADianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taxation Bar Examination 2013 Q&ADokument11 SeitenTaxation Bar Examination 2013 Q&ADianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moot Court ScriptDokument5 SeitenMoot Court ScriptDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial 2011 Bar Exam QuestionnaireDokument21 SeitenRemedial 2011 Bar Exam QuestionnaireAlly BernalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digests Ko 0823Dokument2 SeitenDigests Ko 0823Dianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adarayan Vs RPDokument9 SeitenAdarayan Vs RPDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- BankingDokument121 SeitenBankingDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- BankingDokument121 SeitenBankingDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Political Law NotesDokument100 SeitenPolitical Law NotesJenniferAlpapara-Quilala100% (2)

- Villanueva Vs CA CaseDokument2 SeitenVillanueva Vs CA Casemarwantahsin100% (2)

- 2Dokument1 Seite2Dianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moot Court ScriptDokument5 SeitenMoot Court ScriptDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- BankingDokument121 SeitenBankingDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formal Offer of Evidence of DefenseDokument1 SeiteFormal Offer of Evidence of DefenseDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moot Court ScriptDokument5 SeitenMoot Court ScriptDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 00Dokument4 Seiten00Dianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Star BurnDokument5 SeitenStar BurnDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2Dokument1 Seite2Dianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1) Hyatt Elevators and Escalators Corp. Vs Goldstar Elevators, Phils., Inc., (GR. No. 161026, Oct. 24, 2005)Dokument5 Seiten1) Hyatt Elevators and Escalators Corp. Vs Goldstar Elevators, Phils., Inc., (GR. No. 161026, Oct. 24, 2005)Dianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 80Dokument2 SeitenRule 80Dianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vawc 101 BodyDokument33 SeitenVawc 101 BodyDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crim Pro BarDokument683 SeitenCrim Pro BarCathy PesqueraNoch keine Bewertungen

- VAWC Act ExplainedDokument3 SeitenVAWC Act ExplainedDianne Esidera RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- AsfsadfasdDokument22 SeitenAsfsadfasdJonathan BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICICI Campus - RecruitmentDokument24 SeitenICICI Campus - RecruitmentRobart ThomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Info Change ArticlesDokument54 SeitenInfo Change ArticlesSavan AayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pappu Kumar Yadaw's CAT Exam Admit CardDokument2 SeitenPappu Kumar Yadaw's CAT Exam Admit Cardrajivr227Noch keine Bewertungen

- Santeco v. AvanceDokument13 SeitenSanteco v. AvanceAlthea Angela GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (1959) 1 Q.B. 11Dokument18 Seiten(1959) 1 Q.B. 11Lim Yi YingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factorytalk Batch View Quick Start GuideDokument22 SeitenFactorytalk Batch View Quick Start GuideNelsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cleaner/ Conditioner PurgelDokument2 SeitenCleaner/ Conditioner PurgelbehzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- COMMERCIAL LAW REVIEW - SamplexDokument10 SeitenCOMMERCIAL LAW REVIEW - SamplexML BanzonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sde Notes Lit and Vital Issues FinalDokument115 SeitenSde Notes Lit and Vital Issues FinalShamsuddeen Nalakath100% (14)

- Ontario Municipal Board DecisionDokument38 SeitenOntario Municipal Board DecisionToronto StarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sentencing Practice PDFDokument14 SeitenSentencing Practice PDFamclansNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christmas ArticleDokument1 SeiteChristmas ArticleCricket InfosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Central DirectoryDokument690 SeitenCentral DirectoryvmeederNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budget Programs of Philippine PresidentsDokument6 SeitenBudget Programs of Philippine PresidentsJasper AlcantaraNoch keine Bewertungen

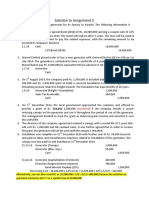

- Assignment 2 SolutionDokument4 SeitenAssignment 2 SolutionSobhia Kamal100% (1)

- Preliminary Chapter and Human RelationsDokument12 SeitenPreliminary Chapter and Human Relationsianyabao61% (28)

- PS (T) 010Dokument201 SeitenPS (T) 010selva rajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Jewish Religion - Chapter 3 - The Talmud and Bible BelieversDokument11 SeitenThe Jewish Religion - Chapter 3 - The Talmud and Bible BelieversNatasha MyersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 14 Exercises - Investments - BodieDokument2 SeitenChapter 14 Exercises - Investments - BodieNguyệtt HươnggNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of ConsentDokument2 SeitenAffidavit of ConsentRocketLawyer100% (1)

- Financial Statement: Funds SummaryDokument1 SeiteFinancial Statement: Funds SummarymorganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articles of Association 1774Dokument8 SeitenArticles of Association 1774Jonathan Vélez-BeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Income Statement and Related Information: Intermediate AccountingDokument64 SeitenIncome Statement and Related Information: Intermediate AccountingAdnan AbirNoch keine Bewertungen

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Hist4344.001.09f Taught by Debra Pfister (DHPF)Dokument8 SeitenUT Dallas Syllabus For Hist4344.001.09f Taught by Debra Pfister (DHPF)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Court Directory and Contact NumbersDokument51 SeitenCourt Directory and Contact NumbersMarion Lawrence LaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perfam Cases 37 UpDokument196 SeitenPerfam Cases 37 UpNina IrayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pop Art: Summer Flip FlopsDokument12 SeitenPop Art: Summer Flip FlopssgsoniasgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remote Access Security Best PracticesDokument5 SeitenRemote Access Security Best PracticesAhmed M. SOUISSINoch keine Bewertungen

- COMMERCIAL CORRESPONDENCE ADDRESSINGDokument44 SeitenCOMMERCIAL CORRESPONDENCE ADDRESSINGKarla RazvanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933–1945Von EverandNazi Germany and the Jews, 1933–1945Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (9)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziVon EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (157)

- All the Gallant Men: An American Sailor's Firsthand Account of Pearl HarborVon EverandAll the Gallant Men: An American Sailor's Firsthand Account of Pearl HarborBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (37)

- Unknown Valor: A Story of Family, Courage, and Sacrifice from Pearl Harbor to Iwo JimaVon EverandUnknown Valor: A Story of Family, Courage, and Sacrifice from Pearl Harbor to Iwo JimaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (7)

- Where the Birds Never Sing: The True Story of the 92nd Signal Battalion and the Liberation of DachauVon EverandWhere the Birds Never Sing: The True Story of the 92nd Signal Battalion and the Liberation of DachauBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (11)

- Modern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesVon EverandModern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (3)

- Darkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the BrinkVon EverandDarkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the BrinkBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (31)

- Highest Duty: My Search for What Really MattersVon EverandHighest Duty: My Search for What Really MattersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarVon EverandHero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (19)

- The Only Thing Worth Dying For: How Eleven Green Berets Fought for a New AfghanistanVon EverandThe Only Thing Worth Dying For: How Eleven Green Berets Fought for a New AfghanistanBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (25)

- Never Call Me a Hero: A Legendary American Dive-Bomber Pilot Remembers the Battle of MidwayVon EverandNever Call Me a Hero: A Legendary American Dive-Bomber Pilot Remembers the Battle of MidwayBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (12)

- The Volunteer: The True Story of the Resistance Hero Who Infiltrated AuschwitzVon EverandThe Volunteer: The True Story of the Resistance Hero Who Infiltrated AuschwitzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saving Freedom: Truman, the Cold War, and the Fight for Western CivilizationVon EverandSaving Freedom: Truman, the Cold War, and the Fight for Western CivilizationBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (11)

- Every Man a Hero: A Memoir of D-Day, the First Wave at Omaha Beach, and a World at WarVon EverandEvery Man a Hero: A Memoir of D-Day, the First Wave at Omaha Beach, and a World at WarBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (10)

- Hubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyVon EverandHubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (23)

- Sacred Duty: A Soldier's Tour at Arlington National CemeteryVon EverandSacred Duty: A Soldier's Tour at Arlington National CemeteryBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (9)

- Dunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureVon EverandDunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (19)

- Hitler's Scientists: Science, War and the Devil's PactVon EverandHitler's Scientists: Science, War and the Devil's PactBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (101)

- No Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesVon EverandNo Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (7)

- Commander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943Von EverandCommander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (16)

- Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day's Black Heroes, at Home and at WarVon EverandForgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day's Black Heroes, at Home and at WarBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (10)

- Dead Reckoning: The Story of How Johnny Mitchell and His Fighter Pilots Took on Admiral Yamamoto and Avenged Pearl HarborVon EverandDead Reckoning: The Story of How Johnny Mitchell and His Fighter Pilots Took on Admiral Yamamoto and Avenged Pearl HarborNoch keine Bewertungen

- Masters and Commanders: How Four Titans Won the War in the West, 1941–1945Von EverandMasters and Commanders: How Four Titans Won the War in the West, 1941–1945Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (43)

- The Life of a Spy: An Education in Truth, Lies, and PowerVon EverandThe Life of a Spy: An Education in Truth, Lies, and PowerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)

- Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler's BestVon EverandFaster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler's BestBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (28)