Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Gombrich Winston Churchill As Painter and Critic

Hochgeladen von

Gabriela Robeci0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

39 Ansichten5 SeitenThis document summarizes and analyzes an article by E.H. Gombrich about Winston Churchill's hobby and skill as a painter. Some key points:

- Churchill took up painting in his 40s and reached a level of competence recognized by the Royal Academy, though some critics denied his work was "art".

- Churchill's style was influenced by Sir William Nicholson and was representative of British painters of his generation, who followed Impressionism rather than Cubism.

- Impressionism's emphasis on painting outdoors and capturing color suited Churchill's abilities as an amateur more than the academic tradition it replaced.

- Churchill was intellectually engaged with painting theory and produced insightful writings on the art

Originalbeschreibung:

Gombrich Winston Churchill as Painter and Critic

Originaltitel

Gombrich Winston Churchill as Painter and Critic

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThis document summarizes and analyzes an article by E.H. Gombrich about Winston Churchill's hobby and skill as a painter. Some key points:

- Churchill took up painting in his 40s and reached a level of competence recognized by the Royal Academy, though some critics denied his work was "art".

- Churchill's style was influenced by Sir William Nicholson and was representative of British painters of his generation, who followed Impressionism rather than Cubism.

- Impressionism's emphasis on painting outdoors and capturing color suited Churchill's abilities as an amateur more than the academic tradition it replaced.

- Churchill was intellectually engaged with painting theory and produced insightful writings on the art

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

39 Ansichten5 SeitenGombrich Winston Churchill As Painter and Critic

Hochgeladen von

Gabriela RobeciThis document summarizes and analyzes an article by E.H. Gombrich about Winston Churchill's hobby and skill as a painter. Some key points:

- Churchill took up painting in his 40s and reached a level of competence recognized by the Royal Academy, though some critics denied his work was "art".

- Churchill's style was influenced by Sir William Nicholson and was representative of British painters of his generation, who followed Impressionism rather than Cubism.

- Impressionism's emphasis on painting outdoors and capturing color suited Churchill's abilities as an amateur more than the academic tradition it replaced.

- Churchill was intellectually engaged with painting theory and produced insightful writings on the art

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 5

E. H.

Gombrich, Winston Churchill as Painter and Critic, The Atlantic,

Vol. 215, 1965, pp.90-3 [Trapp no.1965G.1]

Art criticism can never be objective. No critic is free of prejudices in the original sense of the word, of

judgements, that is, that were before him and determine his outlook and approach. When is comes to

the work of an amateur who is also one of the most famous and controversial figures of his age,

objectivity becomes doubly impossible. His fame enlists our interest by makes us suspicious; his

amateur status spikes the critic's guns. To judge these paintings by professional standards would be

unfair; to make allowances would be patronising. No wonder that crowds flocked, but critics frowned,

when a group of Churchill's landscapes and still lifes toured the United States. Such paintings may

have their value as personal documents, but are they art?

Winston Churchill tried several times to force the issue of objectivity. In 1921 he exhibited in Paris

under the pseudonym of Charles Morin and sold four out of five landscapes for thirty pounds each.

After World War II he submitted two paintings to the Royal Academy under the name of Winter and

got them accepted by the jury. Clearly, this amateur who had begun painting in his forties had

reached a standard of competence that satisfied the guardians of traditional skills.

Things being what they are, however, this test will hardly satisfy those who denied Churchill's

paintings the status of art. If the Academy accepted them, so much the worse. It can only mean that

Churchill was far behind the times.

Now, this fashionable criterion of up-to-dateness need not be taken too seriously either. After all,

paintings are not models of motorcars. But it so happens that any critic who uses this touchstone

delivers himself into the hands of the historian. History can be objective where dates and datedness

are at issue. It finds that Winston Churchill's basic idiom was that of his whole generation of British

painters, a group of artist who were Picasso's seniors by some ten years.

For these men, born in the eighteen seventies, Paris was already the mecca of painting, but it was the

Paris of the impressionists rather than that of the cubists. After the subdued tones of Whistler and of

Sickert, they were beginning to discover the joy of painting boldly in strong colours without retreating

from likeness. None of these artists is well known outside England, except possibly Augustus J ohn,

who was four years younger than Churchill. But J ohn was mainly a portraitist, whose range would

certainly elude the grasp of the aspiring amateur. Churchill found his inspiration in the landscapes

and still lifes of one of the most gifted of this age group, Sir William Nicholson (1872-1949), the father,

by the way, of the abstract artist Ben Nicolson. A future Bernard Berenson might well classify some

of Churchill's best landscapes (such as the Loup River, Quebec, exhibited in the London Tate Gallery)

as "Amico di Sir William," and he would be right, because Nicolson was a frequent guest at Chartwell,

Sir Winston's country home, which houses two of his most attractive works.

Here as elsewhere Churchill was favoured by luck, and here as elsewhere he knew how to exploit his

good fortune. He was lucky to be born into a generation whose artistic idiom was more easily

accessible to the amateur than was any previous style of painting. The tonal painting of the genuinely

academic tradition requires a mastery of conventions and a discipline in their application that easily

defeat amateurs. J ane Austen's ladies painted small watercolours. Oil paintings were beyond them.

To build up a large structure of tonal relationships demanded, if not a genius, at least a professional.

When the impressionists left their studios to paint out of doors, they abandoned this whole procedure

of tonal gradations. Their work was done alla prima; indeed, their concern was to preserve the beauty

and strength of unmixed paint. No one would contend, however, that the idiom of a Monet or a Renoir

is easy. Their research into the alchemy of light effects, their concern with optical mixture that led to

the experiments of the pointillists demand at least as sure an eye and as skilled a hand as the

traditional method had. It was not until the next generation that these skills were somewhat at a

discount. What mattered increasingly was spontaneity, boldness and a certain freshness of vision

that was summed up in the catchword of the "innocent eye." These painters were determined to

observe the local colours and to sing their beauty, regardless of academic rules or scientific caution.

At last, meadows could be painted green and the sea a proper luminous blue.

It must be admitted that this liberation brought its own danger, the danger of triviality. Born as we are

into the succeeding period, we may be particularly sensitive to this proximity of the travel poster, and

even the picture postcard, and therefore prone to overlook the difference between the masters and

the vulgarisers. But a certain risk of obviousness may be inherent in the idiom itself and must have

contributed to the rapid decline in the prestige of the Royal Academy.

It would be an insult to the artist concerned, however, to imagine that they were not aware of these

pitfalls. On the contrary, the traditional problems of painting, questions of tone, of relationships, of

musical composition, and of the sensitive touch, were rarely pondered with more concern and

discussed with more subtlety than by this generation, who were old enough to remember the earlier

values and young enough to divine new possibilities. The volume on Sir William Nicholson in the

Penguin series on Modern Painters contains an introduction by the late Robert Nichols which

admirably catches the painters' conversation about these imponderables: "Tone exists when . . .

everything in your picture sings in harmony"; "the value of the pattern depends on the interestingness

of the shape and relative placings of the dark to the light."

This was the historical moment in which Winston Churchill was initiated into the pleasures and

agonies of painting. He was in his middle forties, a member of the War Cabinet in World War I, and

yet, so he thought, condemned to momentary inactivity. He took up the new hobby with that zest that

was all his own and grasped the whole situation with a clarity and an insight that mark the great

statesman and historian.

For, let not one suppose that he just dabbled with paint with the nave self-satisfaction of the

nonartist. He knew as well as his critics what he owed to his time. His supreme intelligence was

certainly never fooled by the relative ease with which he learned to sketch from nature in the manner

of his friends. Anyone who wants to get a measure of Churchill's mind must read and savor the two

astounding essays, one on "Hobbies," one on "Painting as a Pastime," which he included in Thoughts

and Adventures in 1932 and issued as a little volume in 1948.

There is nothing amateur about these meditations on painting. They beat most professional critics

hollow. He had evidently eavesdropped on the conversations of his painter friends to good purpose.

He had also studied Ruskin and had learned from the great Victorian critic what masters such as

Turner were about. Any British Minister worth his salt must be able to listen to the experts and to

translate and present their findings in more lucid and more vivid terms. To this skill Churchill brought

his genius; with that touch of self-irony that always reconciles us to his rhetoric, he pretended to

understand the painter's problem in terms of a supreme commander fighting a major battle. Maybe

he wanted to reverse the equation: If painting is like generalship, then generalship is like painting,

and a certain great war leader might claim to be a great artist after all. But what matter? For out of

this unpromising comparison he extracts a picture of artistic mastery that deserves to be called

classic:

It is in the use and withholding of their reserves that the great Commanders have generally excelled .

. . . In painting, the reserves consist in Proportion or Relation . . . . At one side of the palette there is

white, at the other black; and neither is ever used "neat". Between these two rigid limits all the action

must lie, all the power required must be generated. Black and white themselves, placed in

juxtaposition, make no great impression; and yet they are the most that you can do in pure contrast.

It is wonderful after one has tried and failed often to see how easily and surely the true artist is

able to produce every effect of light and shade, of sunshine and shadow, of distance or nearness,

simply by expressing justly the relations between the different planes and surfaces with which he is

dealing. We think that this is founded upon a sense of proportion, trained no doubt by practice, but

which in its essence is a frigid manifestation of mental power and size. We think that the same mind's

eye that can justly survey and appraise and prescribe before hand the values of a truly great picture in

one all-embracing regard, in one flash of simultaneous and homogeneous comprehension, would also

with a certain acquaintance with the special technique be able to pronounce with sureness upon any

other high activity of the human intellect. This was certainly true of the great Italians.

In this comprehension of the psychological background of great art, Churchill certainly was far

superior to the purely expressionist school of criticism that is current today. Indeed, some of his

further formulations of the psychological problems of image building and image reading are so acute

and so profound that, as a student of these matters, I could do no better than build them into the

fabric of my book Art and Illusion.

A critic of such acumen surely cannot be suspected of having overlooked the difference between the

artist and the amateur. For those who "go on a joyride in a paintbox . . . audacity is the only ticket."

"Even if only four or five main features are seized and truly recorded, these by themselves will carry a

lot of ill-success or half-success." Churchill knew, of course, that these features must be observed

where alone they can be found in the museum rather than in nature; and he decisively forestalled

any future critic or historian who might accuse him of lack of originality. "The galleries of Europe take

on a new . . . interest." "This, then, is how painted a cataract. Exactly, and there is that same light I

noticed last week in the waterfall at " And so on. "You see the difficulty that baffled you yesterday;

and you see how easily it has been overcome by a great or even by a skilful painter." Observe the

distinction between "great" and "even . . . skilful." It was skill he aimed at, and this he surely

achieved in precisely such effects as the gleam of water he described. "Leave to the masters of art

trained by a lifetime of devotion the wonderful process of picture-building and picture creation. Go out

into the sunlight and be happy with what you see."

But even this love of sunshine carried him beyond the confines of traditional English reserve. For him

it was the French and he includes Matisse "who have so wonderfully vivified, brightened and

illuminated modern landscape painting . . . they have brought back to the pictorial art a new draught of

joie de vivre." His encounter in southern France with "disciples of Czanne," whose manners and

mannerisms are shrewdly observed in his essay, must have opened new horizons to Churchill the

critic.

Whether it really benefited Churchill the painter is a different question. That precarious balance

between traditionalism and modernism sought by the English masters of Churchill's generation can be

so easily upset by apparently innocent concessions. Temperamentally, no doubt, Churchill would

have loved to join the Fauves, the "wild beasts" of the great revolution, but a right instinct, or the

wisdom of age, held him back from what would have been a disastrous flirtation with youth.

Whatever his ultimate achievement, Churchill certainly possessed that quality that is a necessary

though not a sufficient - condition for any artistic genius: the very act of painting was charged for him

with the whole gamut of human emotions. His formulations would find an echo in the heart of many a

young painter who would scarcely waste a glance on his sketches: J ust to paint is great fun. The

colours are lovely to look at and delicious to squeeze out . . . I cannot pretend to feel impartial about

the colours, I rejoice with the brilliant ones, and am genuinely sorry for the poor browns. When I get

to heaven I mean to spend a considerable portion of my first million years in painting, and so get to

the bottom of the subject. But then I shall require a still gayer palette than I get here below. I expect

orange and vermillion will be the darkest, dullest colours upon it, and beyond them there will be a

whole range of wonderful new colours which will delight the celestial eye. Nor would Churchill have

needed a psycho-analyst to reveal to him some of the deeper psychological sources that fed his

pleasures in the painting. His description of his first day at the easel tells its own story as openly and

as reticently as only an artist can who has access to these insights and is so obviously in charge that

he has no reason to fear them: "Fair and white rose the canvas; the empty brush hung poised, heavy

with destiny, irresolute in the air. My hand seemed arrested by silent veto" and then his initiation by

a casual visitor who "splashed into the turpentine" and subdued the "absolutely cowering canvas.

Any one could see that it could not hit back . . . The sickly inhibitions rolled away. I seized the largest

brush and fell upon my victim with Berserk fury. I have never felt any awe of a canvas since."

It is clear that the emotions and instincts that were soon to break through in abstract expressionism

would not have surprised the writer of those lines. What might have surprised him is identification of

such a breakthrough with art. And, in a certain sense, an amateur of genius such as Churchill might

indeed be a test case for any expressionist doctrine of art. This is not the occasion for such a

discussion. Suffice it to say that if art is self expression, this goes for bad no less that for good art.

But expression to whom? That flamboyance that we all associate with Winston Churchill, the streak

of rhetoric can certainly be found in his pictures by those who know them to be Churchill's.

It may be argued that these correspondences between a personality and its expression are both trivial

and deceptive. Hitler, the screaming demagogue, painted tame water-colours. No doubt these too

reflected one side of his character. He would not have painted them otherwise. But nobody could

learn much worth knowing about either of the protagonists of World War II from a contemplation of

their works. Not that the biographer might not enjoy such links as he can discover between Churchill

the man and Churchill the painter. An amateur who could take on the Mont Sainte Victoire,

immortalised by Czanne, may not be a great painter, but he must be a daring one; a statesman who

selects a Beguinage as his motif after the strain of the war years may well express a wistful longing

for a calm haven of retirement.

But such psychologising merely projects into the pictures the extraneous knowledge which the

objective critic wants to avoid. Need he try? Their maker did not. To him, no doubt, his paintings

were records of pleasures, memories of moments of relaxation from the grimmest of cares during the

dark days when he had to watch the approach of what he called "the unnecessary war," and the even

darker ones when he had to fight it through. "If it weren't for painting I could not live," he said. "I

couldn't bear the strain of things." If he was right, his painting may have helped to save Western

civilisation.

Yet Churchill, whose character and outlook have always offended the puritans, has offended most

through this most innocent of his pleasures. There is little love lost, at the best of times, between the

artist and the amateur. The master who has spent another agonising day in front of his canvas,

perspiring with concentration in a desperate effort to get it right, must always be galled by the

enthusiast who tells him painting is relaxing. Indeed, the greater the superficial similarity between the

ultimate outcome of his struggles and the amateur's lucky hit, the tenser the situation will be likely to

get. There may well be an element of understandable envy in this reaction. The amateur is free to

enjoy his successes and to forget about his failures. The artist, alas, cannot afford this privilege of the

irresponsible.

There is an episode from the life of Sir William Nicholson that reminds us of this all-important

difference. When, toward the end of his life, he was honoured with a large retrospective exhibition in

the National Gallery, he was, as he confessed to Robert Nichols, rather pleased with it. "But I said to

myself: 'One never knows....perhaps I'm repeating myself.' And on that I went straight home and I set

myself the hardest possible problem I could find. It entailed between two and three months' solid

painting. Everyday I'd say to myself, 'There - I've got it,' and every morning I'd come down and see I

hadn't. Yes, it was a real jaw-cracker. But I think I've got it."

Surely there are no such "real jaw-crackers" among Churchill's paintings. He found them elsewhere

in the supply of tanks to the Army of the Nile, for instance. But precisely for that reason, Churchill

would have understood his friend Nicholson, and even tried to learn and progress so as to give his

"joyride in a paintbox" a sense of purpose and direction. When Sir J ohn Rothenstein visited the

ageing Prime Minister at Chartwell, his host asked him to criticise the paintings without holding back.

No sooner had the director of the Tate Gallery pointed to a weakness in one of the earlier canvases

than Churchill fetched brush and paint to correct it then and there. We are told that he was most

unwillingly persuaded by the historically minded professional that such belated correction would only

upset the unity of mood.

Maybe he was right in distrusting this critical clich. For one of the things that made Churchill great

was his persistent distrust of the expert. Of course, the distrust was mutual. We need not

adjudicate. But whenever we hear one of the accredited experts calling Churchill names, let us at

least remember that an "amateur" is really a lover, and a "dilettante," one who delights.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Bourne Legacy (Film)Dokument9 SeitenThe Bourne Legacy (Film)Gon FloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timothy J. Clark - From Cubisam To GuernicaDokument327 SeitenTimothy J. Clark - From Cubisam To GuernicaKraftfeld100% (10)

- The Painter's Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in ArtVon EverandThe Painter's Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in ArtBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (5)

- After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated EditionVon EverandAfter the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated EditionBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (26)

- Enjoying Modern Art (Art Ebook)Dokument274 SeitenEnjoying Modern Art (Art Ebook)Prim100% (5)

- History of CaricatureDokument6 SeitenHistory of CaricaturemileatanasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baudelaire's 'On Photography'Dokument2 SeitenBaudelaire's 'On Photography'Ix I ArmentaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arthur Coleman Danto-The Vital Gesture, Franz Kline in RetrospectDokument5 SeitenArthur Coleman Danto-The Vital Gesture, Franz Kline in RetrospectŽeljkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gates of MadnessDokument75 SeitenGates of MadnessJasmine Crystal ChopykNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modern Painting - George MooreDokument286 SeitenModern Painting - George MooreJonathan DuquetteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sir Joshua Reynolds' Discourses: Edited, with an Introduction, by Helen ZimmernVon EverandSir Joshua Reynolds' Discourses: Edited, with an Introduction, by Helen ZimmernNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kitsch and The Modern PredicamentDokument8 SeitenKitsch and The Modern PredicamentCat CatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Charles Baudelaire - The Modern Public and PhotographyDokument6 SeitenCharles Baudelaire - The Modern Public and PhotographyCarlos Henrique SiqueiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Best Portraits in Engraving by Sumner, Charles, 1811-1874Dokument27 SeitenThe Best Portraits in Engraving by Sumner, Charles, 1811-1874Gutenberg.orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kitsch and The Modern PredicamentDokument9 SeitenKitsch and The Modern PredicamentDaniel Mutis SchönewolfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roger Scruton Art KistchDokument10 SeitenRoger Scruton Art KistchGabriel ParejoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timothy J Clark From Cubisam To Guernica - CompressDokument327 SeitenTimothy J Clark From Cubisam To Guernica - Compresskailanysantos441Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lewis, Wyndham - The Demon of Progress in The ArtsDokument58 SeitenLewis, Wyndham - The Demon of Progress in The ArtsEMLNoch keine Bewertungen

- William Morris to Whistler: Papers and addresses on art and craft and the commonwealVon EverandWilliam Morris to Whistler: Papers and addresses on art and craft and the commonwealNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Illustrated Letters and Diaries of the Pre-RaphaelitesVon EverandThe Illustrated Letters and Diaries of the Pre-RaphaelitesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Landseer: A collection of fifteen pictures and a portrait of the painter with introduction and interpretationVon EverandLandseer: A collection of fifteen pictures and a portrait of the painter with introduction and interpretationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baudelaire - The Modern PublicDokument9 SeitenBaudelaire - The Modern PublicGianna LaroccaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The True and the Beautiful (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): In Nature, Art, Morals and ReligionVon EverandThe True and the Beautiful (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): In Nature, Art, Morals and ReligionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concerning The Spiritual in ArtDokument41 SeitenConcerning The Spiritual in ArtJavier CebrianNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Complete Paintings of Durer PDFDokument124 SeitenThe Complete Paintings of Durer PDFAntonTsanev100% (3)

- Dandyism of SensesDokument21 SeitenDandyism of SensesMihaela Canciuc100% (1)

- A Quarterly Review of Contemporary "Abstract" Painting& Sculpture Editor: Myfanwy EvansDokument37 SeitenA Quarterly Review of Contemporary "Abstract" Painting& Sculpture Editor: Myfanwy EvansAliciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Visual ArtsDokument40 SeitenVisual Artsricreis100% (2)

- Abstract Painting in FlandersDokument328 SeitenAbstract Painting in Flandersrataburguer100% (1)

- Ernst Gombrich - in Search of New Standards (Ch. 26)Dokument21 SeitenErnst Gombrich - in Search of New Standards (Ch. 26)Kraftfeld100% (3)

- Cranach CatalogueDokument20 SeitenCranach CatalogueStasaStasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- E.P.Bichardson: Hep TopDokument360 SeitenE.P.Bichardson: Hep TopCatalin George100% (1)

- (Book Review) - em - Barnett Newman - Selected Writings and InterviewDokument3 Seiten(Book Review) - em - Barnett Newman - Selected Writings and InterviewMariana Especiosa Do RosárioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art of ExaggerationDokument32 SeitenArt of Exaggerationkaem123100% (1)

- Caspar David Friedrich. Master of the tragic landscape (5 September 1774 – 7 May 1840)Von EverandCaspar David Friedrich. Master of the tragic landscape (5 September 1774 – 7 May 1840)Noch keine Bewertungen

- E. H. Gombrich - Art and Illusion (1984, Princeton Univ PR) - Libgen - lc-7 PDFDokument15 SeitenE. H. Gombrich - Art and Illusion (1984, Princeton Univ PR) - Libgen - lc-7 PDFYes Romo QuispeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti Modernism EssayDokument3 SeitenAnti Modernism EssayAndrew MunningsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Does Art Matter? Intellect's Visual Arts SupplementDokument21 SeitenWhy Does Art Matter? Intellect's Visual Arts SupplementIntellect Books100% (4)

- Fauvism and Expressnism The Creative Intuition PDFDokument6 SeitenFauvism and Expressnism The Creative Intuition PDFCasswise ContentCreationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kanazawa Museum of Contemporary ArtDokument4 SeitenKanazawa Museum of Contemporary ArtGabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deutsch, Lektion 1 (Alphabet)Dokument6 SeitenDeutsch, Lektion 1 (Alphabet)Gabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unstoppable Yayoi Kusama, Wall Street JournalDokument14 SeitenThe Unstoppable Yayoi Kusama, Wall Street JournalGabriela Robeci100% (1)

- Promising Beginnings? Evaluating Museum Mobile Phone AppsDokument19 SeitenPromising Beginnings? Evaluating Museum Mobile Phone AppsGabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- NY010312 Catalog PDFDokument236 SeitenNY010312 Catalog PDFGabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Brief History of The Mexican Votive Paintings That Inspired Frida Kahlo, ArtsyDokument9 SeitenA Brief History of The Mexican Votive Paintings That Inspired Frida Kahlo, ArtsyGabriela Robeci100% (1)

- Paul Gough Introduction A Terrible Beauty, 2010Dokument37 SeitenPaul Gough Introduction A Terrible Beauty, 2010Gabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prue Stent and Honey Long (Boy Art, Performance, Textile)Dokument75 SeitenPrue Stent and Honey Long (Boy Art, Performance, Textile)Gabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articole El AnatsuiDokument17 SeitenArticole El AnatsuiGabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Most Influential Living Artists of 2016Dokument23 SeitenThe Most Influential Living Artists of 2016Gabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Weather Ccp3Dokument1 SeiteWeather Ccp3Gabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bulgarian Folk Costumes - Symbols and TraditionsDokument36 SeitenBulgarian Folk Costumes - Symbols and TraditionsGabriela Robeci100% (2)

- These Artists Are Giving Knitting A Place in Art History: by Alexxa GotthardtDokument26 SeitenThese Artists Are Giving Knitting A Place in Art History: by Alexxa GotthardtGabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Olafur Eliasson's Spectacular Versailles Takeover Stands Up To Climate ChangeDokument6 SeitenOlafur Eliasson's Spectacular Versailles Takeover Stands Up To Climate ChangeGabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feelings Cards PDFDokument4 SeitenFeelings Cards PDFGabriela RobeciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antenna Vsat Maintenance ProposalDokument11 SeitenAntenna Vsat Maintenance ProposalRachmat HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dcb10 Manual Dunlop DC Brick User ManualDokument2 SeitenDcb10 Manual Dunlop DC Brick User ManualEliah Motlom MoheedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foundation Day Committee Responbilites - 2023Dokument2 SeitenFoundation Day Committee Responbilites - 2023Vijayalakshmi H. M.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Openmind 3 Unit 1 VideoscriptDokument1 SeiteOpenmind 3 Unit 1 VideoscriptTatiana Acosta MalpicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chinese GardenDokument20 SeitenChinese GardenPrerna Kapoor100% (1)

- Compressed Rhubarb Dessert RecipeDokument8 SeitenCompressed Rhubarb Dessert RecipeNohaEl-SherifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti Aging TipsDokument15 SeitenAnti Aging TipsArietta Pieds NusNoch keine Bewertungen

- UPLSDokument4 SeitenUPLSLuqman SyariefNoch keine Bewertungen

- L3 31BTRS06Dokument41 SeitenL3 31BTRS06Tirumalarao PechettyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fuel Pumps QuizDokument4 SeitenFuel Pumps QuizLazaro F GomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Design-Pictionary CollarsDokument5 SeitenFashion Design-Pictionary Collarsapi-271523937Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lenovo V330 20ICB AIO SpecDokument7 SeitenLenovo V330 20ICB AIO SpecMrHSNoch keine Bewertungen

- C26 - Al Wasl Park To Al Qusais Industrial Area Bus Service TimetableDokument12 SeitenC26 - Al Wasl Park To Al Qusais Industrial Area Bus Service TimetableDubai Q&ANoch keine Bewertungen

- Bordwell: Last Year at MarienbadDokument7 SeitenBordwell: Last Year at Marienbadottoemezzo13Noch keine Bewertungen

- I-Q350 RMU, I-Q350 RMU-B3m: Reefer Monitoring UnitDokument2 SeitenI-Q350 RMU, I-Q350 RMU-B3m: Reefer Monitoring UnitMohsin MakkiNoch keine Bewertungen

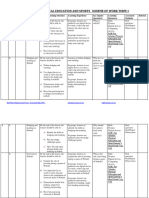

- 2024 Grade 7 Physical Education and Sports Schemes of Work Term 1 KLB Top SchoDokument10 Seiten2024 Grade 7 Physical Education and Sports Schemes of Work Term 1 KLB Top SchokevinsamuelnewversionNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4th Level Pitborn Tiefling GestaltDokument2 Seiten4th Level Pitborn Tiefling GestaltGeorge SawyerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eng - Nmisdbj 1.103 0313Dokument135 SeitenEng - Nmisdbj 1.103 0313mauricio castroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Just Push PlayDokument21 SeitenJust Push PlayIulian StamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Funeral SongsDokument9 SeitenFuneral SongsKenn PacatangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prison Break WorksheetDokument6 SeitenPrison Break Worksheetr_116862476Noch keine Bewertungen

- 50PZ950 3D PresentationDokument190 Seiten50PZ950 3D Presentationwombat666Noch keine Bewertungen

- Christmas Program ScriptDokument4 SeitenChristmas Program ScriptchastineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals of Wireless Module 1 AnswersDokument4 SeitenFundamentals of Wireless Module 1 AnswersAsh_38100% (1)

- Reliance TrendsDokument72 SeitenReliance Trendsdebasis tripathyNoch keine Bewertungen

- AD&D Adventure Gamebooks Sceptre of Power PDFDokument195 SeitenAD&D Adventure Gamebooks Sceptre of Power PDFWerewolf67100% (2)

- What Do You Have For Breakfast?: MR Smith HasDokument2 SeitenWhat Do You Have For Breakfast?: MR Smith HasToñi Varo Garrido67% (3)

- My Life in 2175Dokument1 SeiteMy Life in 2175Angelica BuizaNoch keine Bewertungen