Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Jeffcoate (2008) - One Small Step For Diabetic Podopathy

Hochgeladen von

xtraqrky0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

12 Ansichten3 SeitenDiabetic Foot Pathology

Originaltitel

Jeffcoate (2008) - One Small Step for Diabetic Podopathy

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenDiabetic Foot Pathology

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

12 Ansichten3 SeitenJeffcoate (2008) - One Small Step For Diabetic Podopathy

Hochgeladen von

xtraqrkyDiabetic Foot Pathology

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 3

COMMENTARY

One small step for diabetic podopathy

W. Jeffcoate

Published online: 21 November 2007

# Springer-Verlag 2007

Keywords Amputation

.

Antibiotics

.

Diabetic foot

.

Foot ulcer

.

Gangrene

.

Infection

.

Multiple-drug-resistant organisms

.

Podopathy

Abbreviations

CRP C-reactive protein

IDSA Infectious Diseases Society of America

IWGDF International Working Group on the Diabetic

Foot

The paper by Jeandrot and colleagues in this issue of

Diabetologia sets out to provide evidence in the one

subspecialty area of diabetes in which evidence is most

lacking: disease of the foot. This field is of enormous

importance in terms of both cost and suffering, and yet

remains grossly neglected. There are three main reasons for

this. The first is that no one likes feet, especially those with

chronic ulcers, or which are smelly and necrotic. The

second is that the response to treatment is poor and often

unrewarding, while management tends to be delegated to

nurses and podiatrists. The third is that the field is

extremely complex, and the overlapping influences of

neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease and infection make

trial design difficult. The consequence of this neglect is a

low general level of knowledge about foot care, and an

extremely limited evidence base for treatment strategies.

Many patients are managed badly. The response of the

medical profession to this, predictably, is one of denial, thus

compounding the neglect rather than setting out to rectify it.

There was, for example, not a single oral session on feet at

the recent meeting of the European Association for the Study

of Diabetes. It is time for professional attitudes towards foot

disease in diabetes to come of age, and for the problem to

attract attention commensurate with the suffering it causes.

It is against this background that Jeandrot et al. [1]

provide further evidence to underpin the use of antibiotics,

by examining the response of inflammatory markers to

different clinical grades of infection in the foot. These

grades of infection have been proposed by the Infectious

Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and by the Interna-

tional Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF)

[2, 3]. The grades were originally based on expert opinion

derived from clinical experience, although Lavery et al. [4]

have recently provided supporting evidence by demon-

strating differences in the incidence of amputation between

those with infections of differing grades in 267 newly

presenting ulcers in the USA. If valid, these clinical grades

could be used to categorise infectious events, and could

potentially be linked to management guidelines. They could

provide a basis for comparisons of treatment outcomes in

different centres, and could prove useful in prospective

research. The grades themselves are straightforward in that

they simply rank clinical episodes by severity, but the study

by Jeandrot et al. [1] shows that this ranking is reflected by

differences in levels of inflammatory markers, including C-

reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, and total white cell

and neutrophil counts. Very high levels of response are no

surprise in those with systemic symptoms and signs, of

course, but the real interest of this study lies in the

distinction it makes between those with no clinical signs

Diabetologia (2008) 51:214215

DOI 10.1007/s00125-007-0881-z

W. Jeffcoate (*)

Foot Ulcer Trials Unit, Department of Diabetes and

Endocrinology, Nottingham University Hospitals Trust,

City Hospital Campus,

Nottingham NG5 1PB, UK

e-mail: wjeffcoate@futu.co.uk

and those with mild or moderate infection. Thus, compared

with non-ulcerated controls, the concentration/count of any

individual marker did not differ in those with clinically

non-infected ulcers, whereas the response of every single

inflammatory marker (other than total white cell count) was

greater in those with mild or limited disease (Fig. 1). These

observations confirm the reliability of a clinical diagnosis in

mild or limited infection, and emphasise the need for

appropriate antimicrobial treatment in such cases. They also

suggest that the absence of clinical signs can normally be

relied upon to exclude infection, and hence to identify those

people in whom antimicrobial therapy is not only unnec-

essary but actually contraindicated, for prescribing should

be limited to those in whom there is a clear clinical need.

Jeandrot et al. also compared the ability of different

markers to discriminate between those with and without

evidence of mild infection, and found that CRP and

procalcitonin performed best. They suggest a formula for

combining these two variables to improve discrimination

still further, but I suspect that in practice the non-

availability of procalcitonin assays, not to mention the

need for a calculator, will mean that most clinicians will

rely on just one measurement in combination with the now

validated clinical signs of mild infection.

These interesting results prompt further questions. Al-

though the authors did not specifically address more severe

disease, they found no difference in the inflammatory

responses to mild and to moderate infection, the concen-

trations/counts of all measures (except, possibly, CRP) being

very similar. This suggests that the difference between mild

and moderate grades in the IDSAIWGDF system is not

necessarily based on the severity of the infection itself, but

on the overall condition of the infected lesionits depth, for

instance, or the association with peripheral arterial disease.

The other question that follows from this work is the

extent to which inflammatory markers, such as CRP, or the

suggested CRP/procalcitonin formula, can be used to

determine when soft tissue infection has been eradicated.

If anything, this is an even greater question in clinical

practice and one of the principal difficulties in designing

clinical trials of antimicrobials, for which there is no

specific marker of effectiveness. In clinical practice, it can

be almost impossible to determine when spreading infection

has been eliminated, especially when there is persisting

surface contamination (as is common in ischaemic ulcers).

It can be equally difficult to determine when infection has

been eradicated from bone because the clinical signs of

inflammation sometimes persist beyond the point at which

clinical infection has been arrested. This may occur because

the preceding infection has triggered persistent vasodilata-

tion in those with abnormal vasomotor regulation as a result

of associated neuropathy. The absence of a yardstick for suc-

cessful treatment encourages clinicians (including this one) to

continue antibiotic treatment for longer than is necessary, and

this promotes the spread of resistant organisms. Now that

Jeandrot and colleagues have highlighted the usefulness of

inflammatory markers as a guide to the presence of infection,

it would be feasible to explore their usefulness in determining

when infection has been eliminated. Patients with infection

could be randomised to have treatment discontinued either on

the basis of changes in the chosen inflammatory marker or on

the basis of clinical signs and/or usual practice. If the use of

inflammatory markers results in shorter courses of treatment

with no increase in relapse, it would have an immediate

and major effect on clinical care. It would be a giant leap

forwardnot just in managing infection, but also for the

emerging science of podopathy.

Duality of interest The author declares that there is no duality of

interest associated with this manuscript.

References

1. Jeandrot A, Richard JL, Combescure C et al (2007) Serum

procalcitonin and C-reactive protein concentrations to distinguish

mildly infected from non-infected diabetic foot ulcers: a pilot study.

Diabetologia DOI 10.1007/s00125-007-0840-8

2. Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG et al (2004) Diagnosis and

treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis 39:885910

3. Lipsky BA (2004) A report from the international consensus on

diagnosing and treating the infected diabetic foot. Diabetes Metab

Res Rev 20:S68S77

4. Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Murdoch DP, Peters EJG, Lipsky BA

(2007) Validation of the Infectious Diseases Society of Americas

diabetic foot infection classification system. Clin Infect Dis

44:562565

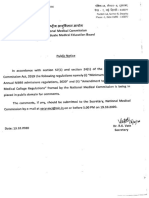

Fig. 1 Signs of mild infection (IDSAIWGDF classification) com-

plicating a pre-existing ulcer: less than 2 cm of surrounding

inflammation, limited to skin and subcutaneous tissues

Diabetologia (2008) 51:214215 215

Reproducedwith permission of thecopyright owner. Further reproductionprohibited without permission.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Gallstone e BookDokument107 SeitenGallstone e Bookee1993Noch keine Bewertungen

- Emergency Department Management of Cellulitis and Other Skin andDokument24 SeitenEmergency Department Management of Cellulitis and Other Skin andJesus CedeñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ATI Ebook - Med SurgDokument702 SeitenATI Ebook - Med SurgMichelle Villanueva100% (4)

- Fax Outpatient Review Form to Beacon Health OptionsDokument1 SeiteFax Outpatient Review Form to Beacon Health OptionsVa KhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Systemic Inflammatory Response SyndromeDokument16 SeitenSystemic Inflammatory Response SyndromeRas RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Identification and Treatment of SepsisDokument4 SeitenEarly Identification and Treatment of Sepsislisa yuliantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gas GangreneDokument21 SeitenGas GangreneSyaIra SamatNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of SurgeryDokument35 SeitenHistory of SurgeryImolaBakosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meaw TechniqueDokument11 SeitenMeaw TechniqueElla Golik100% (4)

- 3 PDFDokument7 Seiten3 PDFAndriawan BramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnostic Techniques For Inflammatory Eye Disease: Past, Present and Future: A ReviewDokument10 SeitenDiagnostic Techniques For Inflammatory Eye Disease: Past, Present and Future: A ReviewAyu Ersya WindiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Insights in Diabetic Foot Infection: Guidelines For Clinical PracticeDokument9 SeitenNew Insights in Diabetic Foot Infection: Guidelines For Clinical PracticebonitalizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glaude Mans 2015Dokument43 SeitenGlaude Mans 2015jessicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetic Foot Infections A Team-Oriented Review of Medical and Surgical ManagementDokument7 SeitenDiabetic Foot Infections A Team-Oriented Review of Medical and Surgical ManagementJessica AdvínculaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeffcoate Et Al. - 2008 - Unresolved Issues in The Management of Ulcers of TDokument10 SeitenJeffcoate Et Al. - 2008 - Unresolved Issues in The Management of Ulcers of TkemsNoch keine Bewertungen

- TRZ 068Dokument8 SeitenTRZ 068salsabilapraninditaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cis 460Dokument6 SeitenCis 460restiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetic Foot Full ThesisDokument5 SeitenDiabetic Foot Full Thesishcivczwff100% (1)

- Diabetic Foot Infection: Antibiotic Therapy and Good Practice RecommendationsDokument10 SeitenDiabetic Foot Infection: Antibiotic Therapy and Good Practice RecommendationsjessicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antibiotic Therapy of Diabetic Foot Infections: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled TrialsDokument37 SeitenAntibiotic Therapy of Diabetic Foot Infections: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled TrialslalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ciz 1197Dokument8 SeitenCiz 1197Lindia PrabhaswariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Does This Patient Have An Infection of A Chronic Wound?: The Rational Clinical ExaminationDokument7 SeitenDoes This Patient Have An Infection of A Chronic Wound?: The Rational Clinical Examinationapi-181367805Noch keine Bewertungen

- Guia Idsa Pie Diabetico PDFDokument42 SeitenGuia Idsa Pie Diabetico PDFAliciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Value of Epi Research in Clinical PracticeDokument6 SeitenValue of Epi Research in Clinical PracticeFouzia ShariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- IDSA GUIDELINES FOR DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF DIABETIC FOOT INFECTIONSDokument42 SeitenIDSA GUIDELINES FOR DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF DIABETIC FOOT INFECTIONSJizus GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Umapathy 2017Dokument11 SeitenUmapathy 2017Karinaayu SerinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Idsa Diabeticfoot2012Dokument42 SeitenIdsa Diabeticfoot2012Prashant LokhandeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Imaging Modalities For The Classification of Gout Systematic Literature Review and Meta-AnalysisDokument7 SeitenImaging Modalities For The Classification of Gout Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysisea793wszNoch keine Bewertungen

- 645 FullDokument8 Seiten645 FullCarrie Joy DecalanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muzii Et Al., 2020Dokument9 SeitenMuzii Et Al., 2020Jonathan LucisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ar 3453Dokument14 SeitenAr 3453Pulmonologi Dan Kedokteran Respirasi FK UNRINoch keine Bewertungen

- Sépsis em Pacientes Neurovascular Focus On Infection and Sepsis in Intensive Care PatientsDokument3 SeitenSépsis em Pacientes Neurovascular Focus On Infection and Sepsis in Intensive Care PatientsEdson MarquesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Evidence Supporting The Revised EORTC-MSGERC Definitions For Invasive Fungal InfectionsDokument2 SeitenThe Evidence Supporting The Revised EORTC-MSGERC Definitions For Invasive Fungal Infectionsgwyneth.green.512Noch keine Bewertungen

- Review Article Stem Cell Therapy For Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Theory and PracticeDokument12 SeitenReview Article Stem Cell Therapy For Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Theory and PracticeNenen DestianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10MJMS26012019 Oa7Dokument8 Seiten10MJMS26012019 Oa7senkonenNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Journal of Foot & Ankle SurgeryDokument4 SeitenThe Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgeryangeldiazdelrio23Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0741521410013315 Main PDFDokument5 Seiten1 s2.0 S0741521410013315 Main PDFNggiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Have Clinical Trials in Sepsis FailedDokument9 SeitenWhy Have Clinical Trials in Sepsis FailedxiaojianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study Protocol For A Randomized Controlled Trial To Test For Preventive Effects of Diabetic Foot Ulceration by Telemedicine That Includes Sensor-Equipped Insoles Combined With Photo DocumentationDokument12 SeitenStudy Protocol For A Randomized Controlled Trial To Test For Preventive Effects of Diabetic Foot Ulceration by Telemedicine That Includes Sensor-Equipped Insoles Combined With Photo DocumentationAna GalvãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jlewnard@berkeley EduDokument24 SeitenJlewnard@berkeley EduRabin BaniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Procalcitonin and AB DecisionsDokument10 SeitenProcalcitonin and AB DecisionsDennysson CorreiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Article: Diabetic Foot Infections: State-Of-The-ArtDokument13 SeitenReview Article: Diabetic Foot Infections: State-Of-The-Artday dayuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jiaa 220Dokument3 SeitenJiaa 220Stephanie HellenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Procalcitonin For Diagnosis of Infection and GuideDokument9 SeitenProcalcitonin For Diagnosis of Infection and GuideSandi AuliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- When Antibiotic Treatment FailsDokument3 SeitenWhen Antibiotic Treatment FailsThai Che100% (1)

- Etiopatogênses Artigo ORIGINALDokument33 SeitenEtiopatogênses Artigo ORIGINALLego is LefeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9 Alavi Et Al., 2014 - Review - Clinical Research On Foot & Ankle Management of Diabetic Foot InfectionsDokument9 Seiten9 Alavi Et Al., 2014 - Review - Clinical Research On Foot & Ankle Management of Diabetic Foot Infectionsbangd1f4nNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microbiology and Antimicrobial Therapy For Diabetic Foot InfectionsDokument10 SeitenMicrobiology and Antimicrobial Therapy For Diabetic Foot InfectionsFanny Marlene BiersackNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Procalcitonin-Guided AntibioticDokument11 SeitenEffect of Procalcitonin-Guided AntibioticRaul ContrerasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sepse TimmingDokument15 SeitenSepse TimmingVictor Hugo SilveiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benedictmitnick2019 PDFDokument9 SeitenBenedictmitnick2019 PDFArthur TeixeiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ana Phy RespiratoryDokument5 SeitenAna Phy Respiratorydayang ranarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microbiology of Diabetic Foot InfectionsDokument13 SeitenMicrobiology of Diabetic Foot InfectionsFida MuhammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- KDokument4 SeitenKDaeng Arya01Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hand Infections CpsDokument11 SeitenHand Infections CpsDavid SidhomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classification of Diabetic Foot WoundsDokument27 SeitenClassification of Diabetic Foot WoundsMARIA HELENA KUSUMASTUTINoch keine Bewertungen

- 10.1515 - CCLM 2022 1072Dokument7 Seiten10.1515 - CCLM 2022 1072ENFERMERIA EMERGENCIANoch keine Bewertungen

- Rheumatoid Arthritis Thesis StatementDokument5 SeitenRheumatoid Arthritis Thesis Statementafjryccau100% (1)

- PMK No. 43 TTG Penyelenggaraan Laboratorium Klinik Yang BaikDokument16 SeitenPMK No. 43 TTG Penyelenggaraan Laboratorium Klinik Yang BaikyantuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apendicitis Antibst NEJ 20Dokument2 SeitenApendicitis Antibst NEJ 20Maria Gracia ChaconNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevention of Foot Ulcer 2020Dokument22 SeitenPrevention of Foot Ulcer 2020Devi SiswaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- DMRR 3280Dokument24 SeitenDMRR 3280purnawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lipsky Et Al 2020 IWGDF Infection GuidelineDokument24 SeitenLipsky Et Al 2020 IWGDF Infection GuidelineFaby BuñayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevention of Infection in Patients With Cancer Evidence Based Nursing InterventionsDokument10 SeitenPrevention of Infection in Patients With Cancer Evidence Based Nursing InterventionsAkshayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dengue Fever Journal 1Dokument10 SeitenDengue Fever Journal 1aurazhavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Weitzenblum - Chronic Cor PulmonaleDokument6 SeitenWeitzenblum - Chronic Cor PulmonalextraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Weitzenblum - Review Series Heart & Lung Disease Cor PulmonaleDokument10 SeitenWeitzenblum - Review Series Heart & Lung Disease Cor PulmonalextraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pearson - Age-Associated Changes in Blood Pressure in A Longitudinal Study of Healthy Men & WomenDokument7 SeitenPearson - Age-Associated Changes in Blood Pressure in A Longitudinal Study of Healthy Men & WomenxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commentary Occupational Factors, Fatigue & Cardiovascular DiseaseDokument5 SeitenCommentary Occupational Factors, Fatigue & Cardiovascular DiseasextraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gupta - Echocardiographic Evaluation of Heart in COPD and Corelation With SeverityDokument6 SeitenGupta - Echocardiographic Evaluation of Heart in COPD and Corelation With SeverityxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bowser (1998) - Biopsy Good Choice For Diagnosing Melanonychia StriataDokument2 SeitenBowser (1998) - Biopsy Good Choice For Diagnosing Melanonychia StriataxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curkendall - COPD Severity & Cardiovascular OutcomesDokument12 SeitenCurkendall - COPD Severity & Cardiovascular OutcomesxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Little - What You Need To Know About Chronic BronchitisDokument4 SeitenLittle - What You Need To Know About Chronic BronchitisxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnosis and Management of Nail PigmentationsDokument13 SeitenDiagnosis and Management of Nail PigmentationsxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kingsbury - Structural Remodelling of Lungs in Chronic Heart FailureDokument10 SeitenKingsbury - Structural Remodelling of Lungs in Chronic Heart FailurextraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baran & Kechijian (1996) - Hutchinson's Sign - A ReappraisalDokument4 SeitenBaran & Kechijian (1996) - Hutchinson's Sign - A ReappraisalxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Selim (2008) - Melanonychia A Question of DensityDokument2 SeitenSelim (2008) - Melanonychia A Question of DensityxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chiacchio Et Al. (2013) - Longitudinal MelanonychiasDokument8 SeitenChiacchio Et Al. (2013) - Longitudinal MelanonychiasxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petrou (2012) - Melanonychia InsightsDokument3 SeitenPetrou (2012) - Melanonychia InsightsxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leung (2008) - Familial Melanonychia StriataDokument4 SeitenLeung (2008) - Familial Melanonychia StriataxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medscape - MelanonychiaDokument5 SeitenMedscape - MelanonychiaxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Linklater (2009) - Anatomy of The Subtalar Joint and Imaging of Talo-Calcaneal CoalitionDokument14 SeitenLinklater (2009) - Anatomy of The Subtalar Joint and Imaging of Talo-Calcaneal CoalitionxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Finch Et Al. (2011) - Fungal MelanonychiaDokument12 SeitenFinch Et Al. (2011) - Fungal MelanonychiaxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stelmach (2003) - The Subtalar Joint in CoalitionDokument5 SeitenStelmach (2003) - The Subtalar Joint in CoalitionxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Selim (2008) - Melanonychia A Question of DensityDokument2 SeitenSelim (2008) - Melanonychia A Question of DensityxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reinsberger Et Al. (2009) - Dose-Dependent Melanonychia by MitoxantroneDokument3 SeitenReinsberger Et Al. (2009) - Dose-Dependent Melanonychia by MitoxantronextraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Morrison & Ferrari (2009) - Inter-Rater Reliability of The Foot Posture Index (FPI-6) in The Assessment of The Paediatric FootDokument6 SeitenMorrison & Ferrari (2009) - Inter-Rater Reliability of The Foot Posture Index (FPI-6) in The Assessment of The Paediatric FootxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kernbach (2010) - Tarsal Coalitions - Etiology, Diagnosis, Imaging, and StigmataDokument13 SeitenKernbach (2010) - Tarsal Coalitions - Etiology, Diagnosis, Imaging, and StigmataxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zaw & Calder (2010) - Tarsal CoalitionsDokument16 SeitenZaw & Calder (2010) - Tarsal CoalitionsxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sakellariou & Claridge (1998) - Tarsal Coalition - Aetiology, Diagnosis and Treatment PDFDokument8 SeitenSakellariou & Claridge (1998) - Tarsal Coalition - Aetiology, Diagnosis and Treatment PDFxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nyska Et Al. (1996) - Posterior Talocalcaneal CoalitionDokument3 SeitenNyska Et Al. (1996) - Posterior Talocalcaneal CoalitionxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sartoris & Resnick (1985) - Tarsal CoalitionDokument8 SeitenSartoris & Resnick (1985) - Tarsal CoalitionxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kelo & Riddle (1998) - Examination and Management of A Patient With Tarsal CoalitionDokument8 SeitenKelo & Riddle (1998) - Examination and Management of A Patient With Tarsal CoalitionxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fopma & McNicol (2002) - Tarsal CoalitionDokument9 SeitenFopma & McNicol (2002) - Tarsal CoalitionxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hayashi Et Al. (2014) - Endoscopic Resection of A Talocalcaneal Coalition Using A Posteromedial ApproachDokument5 SeitenHayashi Et Al. (2014) - Endoscopic Resection of A Talocalcaneal Coalition Using A Posteromedial ApproachxtraqrkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Pharmacy Lecture Notes - Doc LanchaDokument36 SeitenIntroduction To Pharmacy Lecture Notes - Doc LanchaMignot Ayenew100% (1)

- Nonsurgical Rhinoplasty: A Realself Social Media AnalysisDokument4 SeitenNonsurgical Rhinoplasty: A Realself Social Media AnalysisFemale calmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Im Residency FlowchartDokument1 SeiteIm Residency FlowchartF Badruzzama BegumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knee Arthrodesis With Ilizarov Apparatus. Maurizio A.Catagni, Luigi LovisettiDokument54 SeitenKnee Arthrodesis With Ilizarov Apparatus. Maurizio A.Catagni, Luigi LovisettiNuno Craveiro LopesNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Resume Is Finished Resume GeniusDokument1 SeiteMy Resume Is Finished Resume GeniusAllisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary Compassionate Use Remdesivir Gilead - enDokument43 SeitenSummary Compassionate Use Remdesivir Gilead - enlelaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classroom Set-Up Food Vaccine FrequencyDokument5 SeitenClassroom Set-Up Food Vaccine FrequencyLuke Edward PanganibanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 214 Dominican Republic Fact SheetDokument2 Seiten214 Dominican Republic Fact Sheetfedemoncada89Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Case of Hodgkin Lymphoma Presenting As Nephrotic SyndromeDokument6 SeitenA Case of Hodgkin Lymphoma Presenting As Nephrotic SyndromeIJAR JOURNALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stanford - Trauma - Guidelines June 2016 Draft Adult and Peds FINALDokument166 SeitenStanford - Trauma - Guidelines June 2016 Draft Adult and Peds FINALHaidir Muhammad100% (1)

- 香港脊醫 Hong Kong Chiropractors May 2018Dokument18 Seiten香港脊醫 Hong Kong Chiropractors May 2018CDAHKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharm 28 29 30 ExamDokument3 SeitenPharm 28 29 30 Examkay belloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cesarean Birth Care Guide for NursesDokument5 SeitenCesarean Birth Care Guide for NursesVikas MohanNoch keine Bewertungen

- (#5) Benign and Malignant Ovariaan TumorsDokument35 Seiten(#5) Benign and Malignant Ovariaan Tumorsmarina_shawkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 491-Article Text-2225-1-10-20230328Dokument7 Seiten491-Article Text-2225-1-10-20230328Atik TriyanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reports 1Dokument1 SeiteReports 1ziauddin2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Public Notice UgDokument62 SeitenPublic Notice UgAdit AgrawalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Skeletal Muscle Relaxants and Neuromuscular Blocking AgentsDokument7 SeitenSkeletal Muscle Relaxants and Neuromuscular Blocking AgentsYanyan PanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stab WoundsDokument57 SeitenStab WoundsMushtaq AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ambulance ServiceDokument9 SeitenAmbulance ServicedennymxNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHQ GDL 60021 Foreign Body in EarDokument9 SeitenCHQ GDL 60021 Foreign Body in EarfakhrunnisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 SM PDFDokument7 Seiten1 SM PDFFarhatun Qolbiyah YayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prosedur InjeksiDokument7 SeitenProsedur InjeksihackerigdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Myths & Facts in Role of Glimepiride in Managing T2DMDokument38 SeitenMyths & Facts in Role of Glimepiride in Managing T2DMAditya GautamNoch keine Bewertungen