Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Leukore Pada Kehamilan - Evaluation of Vaginal Complaints During Pregnancy The Approach To Diagnosis

Hochgeladen von

Yan Agus AchtiarOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Leukore Pada Kehamilan - Evaluation of Vaginal Complaints During Pregnancy The Approach To Diagnosis

Hochgeladen von

Yan Agus AchtiarCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

PREGNANCY DERMATOSES AND FETAL EXPOSURE (A INGBER AND Y RAMOT, SECTION EDITORS)

Evaluation of Vaginal Complaints During Pregnancy:

the Approach to Diagnosis

Orna Reichman & Michael Gal & Vera Leibovici &

Arnon Samueloff

Published online: 29 June 2014

#Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014

Abstract Vaginal discharge during pregnancy is commonly

accompanied by pruritus, malodor, dysuria, or dyspareunia.

Almost half of pregnant women are estimated to present with

such symptoms. Differential diagnosis is diverse and includes

entities that are specific to pregnancy, some of which may pose

a hazard to maternal and fetal outcomes. Accurate diagnosis is

essential and requires a detailed medical history combined with

a thorough genital examination, measurement of vaginal pH,

and a microscopic evaluation of vaginal secretions (wet

mount). This review will present the approach to diagnosing

vaginal complaints during pregnancy, together with the criteria

and techniques for diagnosing each of the etiologies.

Keywords Vaginal discharge

.

Pregnancy

.

Wet mount

.

Vaginitis

Introduction

Symptoms of vaginal discomfort, including a nonwhite color

discharge, pruritus, malodor, and dyspareunia, are common

during pregnancy. The recently published findings of a

population-based survey conducted in Brazil revealed patho-

logical discharge in 43 % of pregnant women [1]. However,

the symptoms of such condition are nonspecific and shared by

various etiologies. Further, medical history alone does not

provide a sufficient basis for diagnosis [2, 3, 4]. Most causes

of vaginal complaints can be diagnosed by combining medical

history with a thorough genital examination, measurements of

vaginal pH, and wet mount (microscopy of vaginal secretion)

[5, 6]. Cultures and molecular biology assays, based on

nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), such as polymerase

chain reaction (PCR), can help diagnose specific pathogens.

The physiological changes during pregnancy, including

anatomical and hormonal adaptation, aggravate normal

leucorrhea [7]. The cervix contains a collagen-rich connective

tissue with an inner monolayer of columnar cells (endocervix

endocervical glands) that changes dramatically during preg-

nancy. Proliferation and rearrangement of the cervix is strik-

ing, and by the end of pregnancy, the endocervical glands

occupy approximately half the mass of the cervix. This en-

largement causes eversion of the columnar endocervical

glands, known as cervical ectropion. The cervical ectropion

tissue tends to bruise easily; gentle touch (e.g., coitus, PAP

smear, cervical sampling) tends to cause bleeding. Further-

more, the endocervical mucus glands produce a copious

amount of tenacious mucus that contains immunoglobulins

and cytokines and serves as an immune barrier to protect the

pregnancy from ascending infection, as well as a mechanical

obstruction of the cervical canal [7].

In addition to the physiological changes during pregnancy

that aggravate vaginal complaints, the differential diagnosis of

pathological conditions includes entities that are unique to

pregnancy, such as the premature rupture of membranes and

chorioamnionitis, which could both present with vaginal dis-

charge as a primary symptom [7]. These conditions may pose

hazards to maternal and fetal outcomes, including maternal

O. Reichman

:

M. Gal

:

A. Samueloff

OBGYN, Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Hebrew University,

Jerusalem, Israel

M. Gal

e-mail: galm@szmc.org.il

A. Samueloff

e-mail: smuelof@cc.huji.ac.il

V. Leibovici

Hadassah Medical School, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel

e-mail: Rveralibo@hadassah.org.il

O. Reichman (*)

DivisionOBGYN, Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Hebrew

University Medical School, Jerusalem, Israel

e-mail: orna.reich@gmail.com

Curr Derm Rep (2014) 3:159164

DOI 10.1007/s13671-014-0083-0

160 Curr Derm Rep (2014) 3:159164

and fetal morbidity and mortality. Therefore, accurate diagno-

sis of vaginal symptoms during pregnancy is vital.

This review will present the approach to diagnosing vagi-

nal complaints during pregnancy. Criteria and techniques for

diagnosing each of the etiologies will be detailed.

The Approach to Diagnosing Vaginal Complaints

During Pregnancy

Confirm That Symptoms Actually Originate from the Vagina

Fromour experience, most women do not distinguish between

the vulva and vagina and refer to the genital area as one entity.

Proper evaluation of vaginal complaints necessitates a thor-

ough genital examination to verify with the patient the

location of symptoms and to confirm that the discomfort

originates or at least involves the vagina. If the discomfort is

isolated to close anatomical areas, such as the vulva, vestibule,

or perineum, a different differential diagnosis should be pur-

sued. It is advisable during examination to touch gently with a

cotton-tipped applicator the various anatomical genital struc-

tures, including the labia major, labia minor, inter-labial sulci,

perineum, perianal area, vestibule, and clitoris, and only then

to evaluate the vagina. This will help focus the location of the

problem and narrow the differential diagnosis.

Performing a Speculum Examination to Evaluate the Cervix

and Vagina

Check if there is watery discharge secreted from the cervix. A

clear or greenish color indicates meconium and suggests pre-

mature rupture of the membranes. Observe the cervix and

verify if there is an active ectropion. Make sure there is no

abnormal lesion suspicious of cervical carcinoma and that the

PAP smear is normal. Cervicitis is defined by either (1)

purulent or mucopurulent endocervical exudate, visible in

the endocervical canal or by an endocervical swab specimen

and (2) endocervical bleeding caused by gentle passage of a

cotton swab through the cervical os [8]. If cervicitis is

diagnosed, perform a screening test for sexually transmitted

diseases (STDs), focused on Neisseria gonorrhea, Chlamydia

trachomatis, and Trichomonas vaginalis [8]. Of the various

sexually transmitted diseases, these three have the potential to

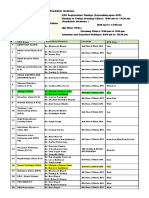

Fig. 1 pH more than and less than 4.5. a *Trichomonas vaginalis has a

wide clinical presentation; some patients present with acute vaginitis and

complain of dyspareunia; malodorous, purulent discharge and itch; the

others (up to 50 %) are asymptomatic. #Gonorrhea and Chlamydia

chlamydia is usually asymptomatic, both can cause cervicitis, diagnosis is

with NAATs (nucleic acid amplification tests). +Chorioamnionitisthe

level of vaginal pH in pregnant women with chorioaminionitis is not

reported in the English literature. **Maternal/fetal sepsis,

chorioamnionitissee criteria for diagnosis in Table 1. b *Yeast

infection has a wide clinical presentation. Symptoms can include

discharge only or a combination of discharge itch and dyspareunia.

Some women are asympt omat i c. **Mat ernal / f et al sepsi s,

chorioamnionitissee criteria for diagnosis in Table 1

Fig. 2 Epithelial cells are shown

by the black arrows. In 2a, 2b,

and 2c the cells are squamous

cells (matured epithelial cells)

with enlarged cytoplasm and a

small nuclei in contrast to

inflammatory conditions (2d) that

the cells are immature (parabasal,

intermediate cells) and have an

enlarged nuclei compared to the

cytoplasm with excess in

inflammatory cells (dashed

arrow). Clue cells are epithelial

cells with abnormal flora adhered

to the borders of the cell. They are

the hallmark of bacterial

vaginosis (2c dashed arrow). The

flora is shown by the wide white

arrow. Normal morphology of

rods is present in picture 2a and

abnormal morphology of cocci

(characteristic of BV) is present in

2c

Curr Derm Rep (2014) 3:159164 161

Table 1 Etiologies that cause vaginal symptoms during pregnancy and their diagnostic criteria

Etiology Diagnostic criteria

Pregnancy specific Premature rupture

of membranes

1. Clinical diagnosisper speculum visualization of amniotic fluid originating from the uterus.

2. Nitrazine test [10] (amniotic fluid pH>7)inexpensive, nonspecific

3. Presence of arborization (ferning), a characteristic of dried amniotic fluid on a slide

4. Placental alpha microglobulin-1 (AmniSure [11])not affected by semen or blood, expensive

5. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 (Actim Prom [12])not affected by semen,

blood, or urine

6. Fetal fibronectin [13]a negative result excludes membrane rupture

7. Oligohydramnios/anhydramnios, combined with an appropriate medical history

8. Equivocal casesinject indigo carmine to amniotic fluid while a tampon is inserted in the

vagina

Chorioamnionitis Clinical chorioamnionitis: maternal fever 38 C and at least two of the following

(after excluding other causes of sepsis) [14]:

1. Maternal tachycardia (<100 beats/min(

2. Maternal leukocytosis (>15,000 cells/mm(

3. Fetal tachycardia (>160 beats/min)

4. Uterine tenderness

5. Foul odor of the amniotic fluid

The level of vaginal pH in pregnant women with chorioaminionitis is not reported in the English

literature.

Microbiological chorioamnionitis [15] when clinical presentation is equivocal and diagnosis is

crucial.

Perform amniocentesis

1. Culture for bacteria

2. Perform a gram stain, search for presence of leukocyte esterase, check glucose concentration,

and verify levels of white blood cells

Cervical mucus plug Clinical diagnosisdetachment of the cervical mucus plug bloody show, commonly followed

by labor, can appear after a digital vaginal examination [8]

Vaginal bleeding antenatal

bleeding (abruption)

Clinical diagnosisper speculum visualization of blood originating from the uterus

Infectious diseases Yeast most common

Candida Albicans

1. Presence of Candida on wet mount or Grams [16, 17]

2. Positive yeast culture [16, 17]

Vaginal pH is in the normal range

Trichomonas vaginalis 1. Presence of motile trichomonas on wet mount

2. Elevated vaginal pH (>4.5)

3. Commercially available nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) [8]gold standard

4. Rapid antigen test immunochromatography (OSOM Trichomonas Rapid Test (Genzyme))

5. Culture on Diamonds mediumpreviously the gold standard, takes 7 days, less commonly

used at present

Bacterial vaginosis Amsels criteria [18], at least three of the following:

1. Pasty discharge

2. Positive whiff test a drop of KOH to vaginal discharge will worsen malodor

3. Positive clue cells on wet mount

4. Elevated pH

Nugent score [19]the score is determined by the average number of one of three morphotypes

of bacteria

03 normal, 46 intermediate, 710 bacterial vaginosis

1. Lactobacillus (04)

2. Gardnerella and Bacteroides (04)

3. Curved gram variable rods (02)

Neisseria gonorrhea,

Chlamydia trachomatis

Clinically could present as cervicitis but most patients with C. trachomatis are asymptomatic.

Diagnosis is based on commercially available nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) [8]

Group A Streptococcus Positive vaginal culture

Immune induced Erosive lichen planus (ELP) Primarily a clinical diagnosis. A biopsy may be obtained to support the clinical diagnosis.

Sometimes immunofluorescence helps to diagnose [20]

Desquamative inflammatory

vaginitis (DIV)

Clinical syndrome of purulent vaginitis, diagnosis is based on the exclusion of causes of

purulent vaginitis [21]

Hormonal/

physiological

conditions

Normal leucorrhea

Cervical ectropion

162 Curr Derm Rep (2014) 3:159164

cause cervicitis or vaginitis and can present with vaginal

symptoms as the chief complaint. The gold standard screening

for these infections is by NAATs, including PCR and ligase

chain reactions that are performed by sampling the cervix/

vagina with one of the currently available commercial appli-

cators. Other STDs that involve the genital area, such as

syphilis (Treponema pallidum), genital warts (human papillo-

ma virus), and genital herpes rarely involve the vagina alone;

the lesion and discomfort primarily involve the vulva, perine-

um, perianal area, and the vestibule. It is important to realize

that if screening is positive for one of the STDs, screening for

all other STDs is necessary, including those that do not cause

vaginal symptoms. After evaluation of the cervix, the vaginal

walls should be examined for redness, petechiae, and erosions.

The appearance of discharge detected visually with bare eyes

is nonspecific and should not lead to diagnosis [2, 3].

Measuring pH of the Vaginal Walls

Vaginal pH reflects the hormonal and bacterial status of the

vagina and is an excellent screening tool for evaluating vaginal

health (Fig. 1a, b). The vaginal epithelium, a dynamic strati-

fied squamous tissue that undergoes maturation in response to

estrogen, is characterized by three cell types, all originating

from the basal layer: the parabasal cells, the intermediate cells

(which are enriched with glycogen), and the squamous cells.

This multiple layer serves to protect the tissue from friction

injury [9]. Vaginal microbiota is in a delicate equilibrium with

hormones. The enriched glycogen in the intermediate cells

acts as a precursor of pyruvate and facilitates the growth of

the hydrogen peroxide producing Lactobacilli, which ferment

pyruvate to lactic acid and induce an acidic pH of 4.00.5.

The acidic environment inhibits growth of anaerobic bacteria

[9]. Normal vaginal pH indicates (1) adequate levels of estro-

gen, (2) a multilayer epithelium (the presence of at least

intermediate cells with glycogen), and (3) healthy microbiota

with predominant hydrogen peroxide producing Lactobacilli.

A normal pH 4.5 likely rules out premature rupture of mem-

branes, bacterial vaginosis, T. vaginalis, and inflammatory

conditions such as desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

(DIV) and erosive lichen planus (ELP).

To measure vaginal pH, obtain, with a cotton-tipped

applicator, a sample from the mid lateral vaginal wall

and measure the pH with a narrow-range paper 4.07.0.

This is a simple, quick, and inexpensive test. Most

importantly, it narrows the differential diagnosis. It is

important to realize that elevated pH can result from

nonpathological conditions such as post antibiotic treat-

ment and douchi ng ( t r ans i ent er adi cat i on of

Lactobacilli), post coitus (sperm elevates pH), and mu-

cus discharge originating from the cervix. In such cases,

a microscope examination of vaginal secretions (wet

mount) is necessary.

Performing a Wet Mount (Microscopy of Vaginal Secretions)

A health care provider with adequate training in microscopy

of vaginal secretions is capable of defining the maturation

status of vaginal epithelium, describing the morphology of

vaginal flora, and detecting excess inflammatory cells and

pathogens including yeast and Trichomonas [6]. Wet mount

is especially important in cases of elevated vaginal pH

(Fig. 1a), to distinguish between true pathologies and false-

positive screening. The latter includes post antibiotic treat-

ment, post douching, and post coitus. To prepare a wet mount,

obtain, with a cotton-tipped applicator, a sample from the mid

lateral vaginal wall and spread on two separate microscopic

slides. Drip on one sample a drop of 0.9 % saline and on the

other a drop of 10 % potassium hydrochloride (KOH). Apply

a cover slide on each drop. Observe with a microscope,

initially magnified 100 and subsequently magnified 400.

Figure 2 depicts a wet mount of four common conditions: (2a)

normal wet mount, (2b) yeast infection, the lined arrows

indicate hyphae and budding yeast, (2c) bacterial vaginosis

(BV), and (2d) inflammatory vaginitis (Fig. 2).

Diagnostic Criteria for Etiologies Causing Vaginal

Symptoms During Pregnancy

The various etiologies causing vaginal symptoms during preg-

nancy and their diagnostic criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 (continued)

Etiology Diagnostic criteria

Contact dermatitis Various creams and lubrications Suggestive exposure based on history. Confirm diagnosis by an allergy test

Allergy to latex (condoms)

Allergy to sperm

Miscellaneous Trauma, post coitus, foreign

body, douching, urine

incontinence

Suggestive, based on history

Curr Derm Rep (2014) 3:159164 163

Conclusions

Accurate diagnosis of vaginal discharge during pregnancy is

important. Though the differential diagnosis is diverse, the

tools required are accessible and uncomplicated. While the

symptoms are nonspecific, the term nonspecific vaginitis

can be avoided as Gardner wrote, over 30 years ago [22]

any knowledgeable physician owning a vaginal speculumand

a microscope should rarely find the need for using the diag-

nosis non specific vaginitis, and that its frequent use might

well imply carelessness, indifference or a failure to employ

available diagnostic methods

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest O Reichman, M Gal, V Leibovici, and A

Samueloff declare no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does

not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any

of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been

highlighted as:

Of major importance

1. Fonseca TM, Cesar JA, Mendoza-Sassi RA, Schmidt EB.

Pathological vaginal discharge among pregnant women: pattern

of occurrence and association in a population-based survey.

Obstet Gynecol Int. 2013;2013:590416.

2. Diseases characterized by vaginal discomfort. Sexual transmitted

disease treatment guidelines, 2010 http://www.cdc.gov/std/

treatment/2010/vaginal-discharge.htm (last entered May 6 2014).

3. Anderson MR, Klink K, Cohrssen A. Evaluation of vaginal com-

plaints. JAMA. 2004;291(11):136879. A mile stone paper inte-

grating 18 publications calculating the sensitivity, specificity and

likelihood ratio of symptoms and signs for evaluating vaginal

complaints.

4. Trichomoniasis and bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy: inadequately

managed with the syndromic approach. Bulletin of the World

Health Organization http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes (last

entered May 6 2014).

5. The vulva and vagina manual, Dennerstein G, Scurry J, Brenan J,

Allen D, Grazia M. M, Gynederm Publishing 2005.

6. Kottmel A, Petersen EE. Vaginal wet mount. J Sex Med.

2013;10(11):26169.

7. Williams Obstetric 23rd edition 2010 p.109, 1168.

8. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC), Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guide-

lines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1110. This

is the gold standard for diagnosing and treating sexual transmitted

diseases.

9. Buchanan DL, Kurita T, Taylor JA, Lubahn DB, Cunha GR, Cooke

PS. Role of stromal and epithelial estrogen receptors in vaginal

epithelial proliferation, stratification and cornification.

Endocrinology. 1998;139:434552.

10. Seeds AE, Hellegers AU. Acid-base determinations in human

amniotic fluid throughout pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

1968;101(2):257.

11. Lee SE, Park JS, Norwitz ER, Kim KW, Park HS, Jun JK.

Measurement of placental alpha-microglobulin-1 in cervicovaginal

discharge to diagnose rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol.

2007;109(3):634.

12. Darj E, Lyrens S. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1, a

quick way to detect amniotic fluid. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand.

1998;77(3):295.

13. Eriksen NL, Parisi VM, Daoust S, Flamm B, Garite TJ, Cox SM.

Fetal fibronectin: a method for detecting the presence of amniotic

fluid. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80(3 Pt 1):4514.

14. Newton ER. Chorioamnionitis and intraamniotic infection. Clin

Obstet Gynecol. 1993;36(4):795.

15. Gauthier DW, Meyer WJ. Comparison of gram stain, leukocyte

esterase activity, and amniotic fluid glucose concentration in

predicting amniotic fluid culture results in preterm premature rup-

ture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(4 Pt 1):1092.

16. Mandell: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice

of Infectious Diseases, 7

th

ed. 2009 churchil Livingston.

17. Centers for disease control and prevention: diagnosing and testing

for genital vulvo-vaginal candidiasis http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/

diseases/candidiasis/genital/diagnosis.html (last entered MAY 6)

18. Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KS, Eschenbach DA,

Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and micro-

bial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:1422.

This is the classic paper for the clinical criteria of diagnosing

bacterial vaginosis.

19. Nugent RP. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:291.

20. Helander SD, Rogers RS. The sensitivity and specificity of direct

immunofluorescence testing in disorders of mucous membranes. J

Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(1):65.

21. Sobel JD, Reichman O, Misra D, Yoo W. Prognosis and treatment

of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol.

2011;117(4):8505.

22. Gardner HL. Non specific vaginitis: a non-entity. Scand J Infec

Dis Suppl. 1983;40:710.

164 Curr Derm Rep (2014) 3:159164

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Writing Committee:: Guidelines For All Doctors in The Diagnosis and Management of Migraine and Tension-Type Headache 2004Dokument53 SeitenWriting Committee:: Guidelines For All Doctors in The Diagnosis and Management of Migraine and Tension-Type Headache 2004Yan Agus AchtiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dapus 2Dokument4 SeitenDapus 2Yan Agus AchtiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpreting Chest X-Rays: Illustrated With 100 CasesDokument5 SeitenInterpreting Chest X-Rays: Illustrated With 100 CasesYan Agus AchtiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Midland College Syllabus Fall 2008 RSPT 1307 Cardiopulmonary Anatomy and Physiology (3-0-0) Course DescriptionDokument6 SeitenMidland College Syllabus Fall 2008 RSPT 1307 Cardiopulmonary Anatomy and Physiology (3-0-0) Course DescriptionYan Agus AchtiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dapus 3Dokument10 SeitenDapus 3Yan Agus AchtiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Yan Agus FK UjDokument5 SeitenJurnal Yan Agus FK UjYan Agus AchtiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kedokteran 092010101002 Bambang PrabawigunaDokument6 SeitenKedokteran 092010101002 Bambang PrabawigunaYan Agus AchtiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- List Game Goman PC GamesDokument321 SeitenList Game Goman PC GamesYan Agus AchtiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abnormal Labor-ModifiedDokument8 SeitenAbnormal Labor-ModifiedListya NormalitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gyeke Et Al Paper 1 Vol 17 4Dokument18 SeitenGyeke Et Al Paper 1 Vol 17 4Yan Agus AchtiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- DH VSCC Intern Manual 4th Edition - WEB PDFDokument124 SeitenDH VSCC Intern Manual 4th Edition - WEB PDFXyzNoch keine Bewertungen

- GQ USA - March 2023Dokument120 SeitenGQ USA - March 2023davidtorrez1988Noch keine Bewertungen

- Neuroimaging Advances in Holoprosencephaly: Re Ning The Spectrum of The Midline MalformationDokument13 SeitenNeuroimaging Advances in Holoprosencephaly: Re Ning The Spectrum of The Midline Malformationfamiliesforhope100% (1)

- Intensive Care Unit (ICU)Dokument36 SeitenIntensive Care Unit (ICU)ruind99hjhkj100% (1)

- ACLSDokument275 SeitenACLSShajahan SideequeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vasospasm: Endothelial Cell InjuryDokument4 SeitenVasospasm: Endothelial Cell InjuryPuja ArgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutrition and AIDSDokument250 SeitenNutrition and AIDSLies Pramana SariNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAREGIVING NC II Lecture Week 6and 7Dokument15 SeitenCAREGIVING NC II Lecture Week 6and 7Ivy MagdayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kanukula 2019Dokument7 SeitenKanukula 2019Dianne GalangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sarcoidosis y UveitisDokument10 SeitenSarcoidosis y UveitisJavier Infantes MolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preeclampsia and EclampsiaDokument24 SeitenPreeclampsia and EclampsiaAngel Marie TeNoch keine Bewertungen

- B Arab Board For Community Medicine Examination Edited 6 1Dokument115 SeitenB Arab Board For Community Medicine Examination Edited 6 1Sarah Ali100% (2)

- Bimanual Vaginal Examination - OSCE Guide - Geeky MedicsDokument6 SeitenBimanual Vaginal Examination - OSCE Guide - Geeky MedicsJahangir AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Correction of Severe Bimaxillary ProtrusionDokument37 SeitenCorrection of Severe Bimaxillary ProtrusionRobbyRamadhonieNoch keine Bewertungen

- NearfatalasthmaDokument8 SeitenNearfatalasthmaHeath HensleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pengaruh Pemberian Ropivakain Infiltrasi Terhadap Tampilan Kolagen Di Sekitar Luka Insisi Pada Tikus WistarDokument10 SeitenPengaruh Pemberian Ropivakain Infiltrasi Terhadap Tampilan Kolagen Di Sekitar Luka Insisi Pada Tikus WistarKunni MardhiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- ThyrotoxicosisDokument16 SeitenThyrotoxicosisFiorella Peña MoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5.respiratory Distress Dental LectureDokument40 Seiten5.respiratory Distress Dental LecturehaneeneeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study #3 Renal 1. LabDokument9 SeitenCase Study #3 Renal 1. Labapi-207971474Noch keine Bewertungen

- Blood Donation RequirementsDokument29 SeitenBlood Donation RequirementsMaria Cecilia FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seattle Angina QuestionnaireDokument6 SeitenSeattle Angina QuestionnaireAmelia SianiparNoch keine Bewertungen

- Camh Suicide Prevention HandbookDokument96 SeitenCamh Suicide Prevention Handbook873810skah100% (3)

- OPD Schedule DoctorsDokument3 SeitenOPD Schedule DoctorssahilNoch keine Bewertungen

- b53 Swasa Kosa Mudra 07Dokument3 Seitenb53 Swasa Kosa Mudra 07shadowfalcon03Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment Diagnosis Goals and Objectives Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationDokument3 SeitenAssessment Diagnosis Goals and Objectives Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationCrissa AngelNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Drama ScriptDokument7 SeitenEnglish Drama ScriptNadia ASNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appenndix C CompleteDokument2 SeitenAppenndix C Completebrooksey2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Burns and ScaldsDokument14 SeitenBurns and ScaldsMuhamad IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual Lifegain INGLESDokument207 SeitenManual Lifegain INGLESNicolás Di LulloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Symptoms: Products & ServicesDokument20 SeitenSymptoms: Products & ServicesLany T. CataminNoch keine Bewertungen